Can Molecular Pathology Drive Progress in Microbiome Understanding? Lessons from Spousal and Household Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

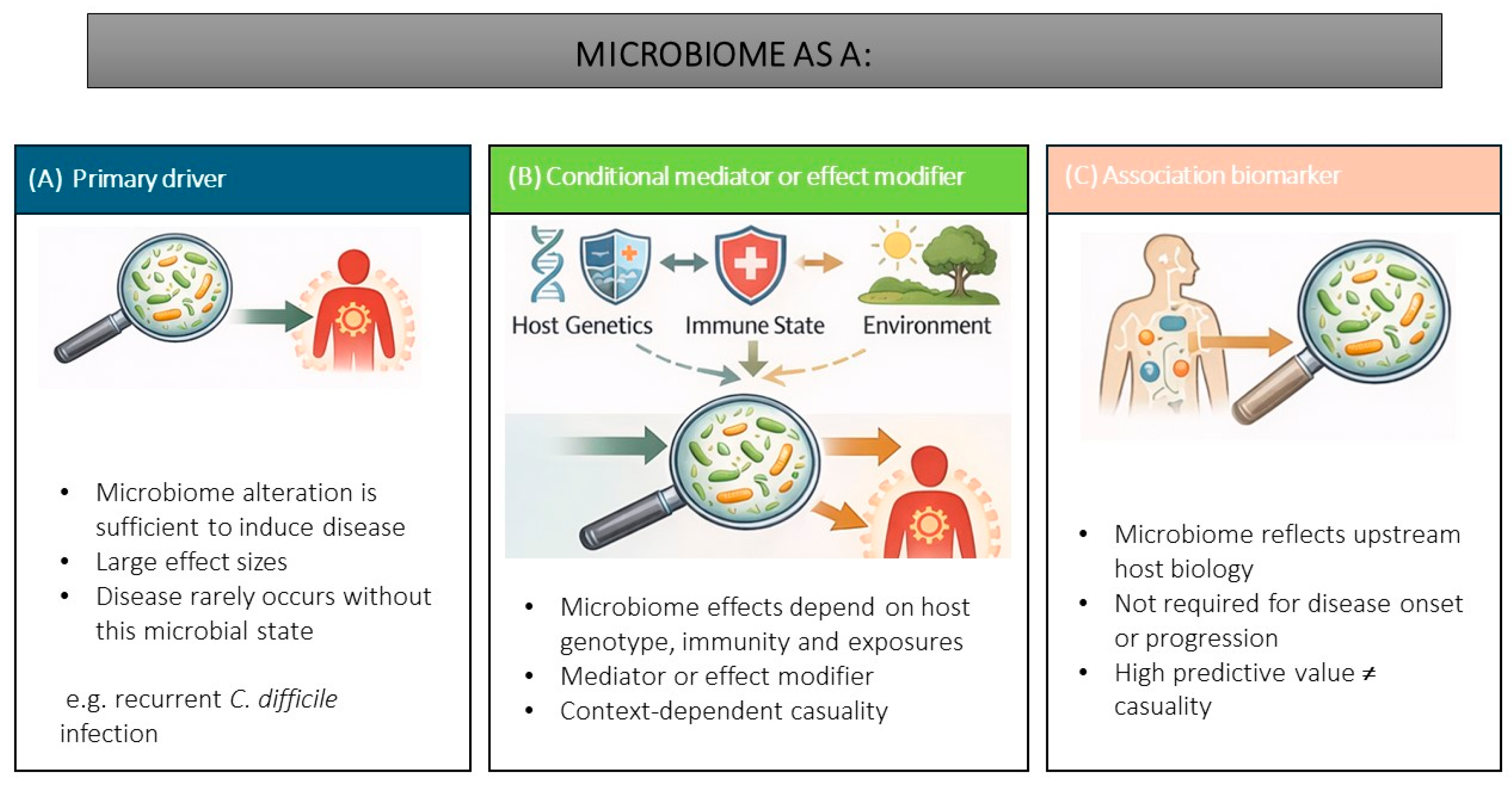

2. Conceptualising Microbiome Causality

2.1. Microbiome as Primary Disease Risk Driver

2.2. Conditional Mediator or Effect Modifier

2.3. Association Biomarker

2.4. Methods and Search Strategy

3. Mechanistic Framework: Homeostasis, Allostasis and Allostatic Load

4. The Human Microbiome as a Host-Constrained, Environmentally Modulated System

5. Marital and Cohabiting Pairs as Natural Experiments in Microbiome Causality

5.1. Metabolic and Cardiometabolic Disorders

5.2. Oral Conditions

5.3. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Other Immune-Mediated Diseases

5.4. Neurodegenerative Diseases

5.5. Longevity and Healthy Ageing

6. Future Directions

6.1. Implications for Interventions and Clinical Translation

6.2. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Human Microbiome Project Consortium. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 2012, 486, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Microbiome Project Consortium. The Integrative Human Microbiome Project: Dynamic analysis of microbiome-host omics profiles during periods of human health and disease. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 16, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Microbiome Project Consortium. The Integrative Human Microbiome Project. Nature 2019, 569, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüssow, H. The relationship between the host genome, microbiome, and host phenotype. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 1170–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brüssow, H. The human microbiome project at ten years—Some critical comments and reflections on “our third genome”, the human virome. Microbiome Res. Rep. 2023, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, J.; Armet, A.M.; Finlay, B.B.; Shanahan, F. Establishing or Exaggerating Causality for the Gut Microbiome: Lessons from Human Microbiota-Associated Rodents. Cell 2020, 180, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcon, A.R.; Turvey, S.; Caulfield, T. ‘Gut health’ and the microbiome in the popular press: A content analysis. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e052446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metwaly, A.; Kriaa, A.; Hassani, Z.; Carraturo, F.; Druart, C.; Arnauts, K.; Wilmes, P.; Walter, J.; Rosshart, S.; Desai, M.S.; et al. A Consensus Statement on establishing causality, therapeutic applications and the use of preclinical models in microbiome research. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 22, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corander, J.; Hanage, W.P.; Pensar, J. Causal discovery for the microbiome. Lancet Microbe 2022, 3, e881–e887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, K.H.; Yarmolinsky, J.; Giovannucci, E.; Lewis, S.J.; Millwood, I.Y.; Munafò, M.R.; Meddens, F.; Burrows, K.; Bell, J.A.; Davies, N.M.; et al. Applying Mendelian randomization to appraise causality in relationships between nutrition and cancer. Cancer Causes Control 2022, 33, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, R.G.; Davenport, E.R. The relationship between the gut microbiome and host gene expression: A review. Hum. Genet. 2021, 140, 747–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dill-McFarland, K.A.; Tang, Z.Z.; Kemis, J.H.; Kerby, R.L.; Chen, G.; Palloni, A.; Sorenson, T.; Rey, F.E.; Herd, P. Close social relationships correlate with human gut microbiota composition. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.A.; Doxey, A.C.; Neufeld, J.D. The Skin Microbiome of Cohabiting Couples. mSystems 2017, 2, e00043-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valles-Colomer, M.; Blanco-Míguez, A.; Manghi, P.; Asnicar, F.; Dubois, L.; Golzato, D.; Armanini, F.; Cumbo, F.; Huang, K.D.; Manara, S.; et al. The person-to-person transmission landscape of the gut and oral microbiomes. Nature 2023, 614, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Nood, E.; Vrieze, A.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Fuentes, S.; Zoetendal, E.G.; de Vos, W.M.; Visser, C.E.; Kuijper, E.J.; Bartelsman, J.F.; Tijssen, J.G.; et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodrich, J.K.; Waters, J.L.; Poole, A.C.; Sutter, J.L.; Koren, O.; Blekhman, R.; Beaumont, M.; Van Treuren, W.; Knight, R.; Bell, J.T.; et al. Human genetics shape the gut microbiome. Cell 2014, 159, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurilshikov, A.; Medina-Gomez, C.; Bacigalupe, R.; Radjabzadeh, D.; Wang, J.; Demirkan, A.; Le Roy, C.I.; Raygoza Garay, J.A.; Finnicum, C.T.; Liu, X.; et al. Large-scale association analyses identify host factors influencing human gut microbiome composition. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wade, K.H.; Hall, L.J. Improving causality in microbiome research: Can human genetic epidemiology help? Wellcome Open Res. 2020, 4, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, J.; Echeverría, C.E.; Maldonado-Noboa, I.; Ojeda-Mosquera, S.; Hidalgo-Tinoco, C.; López-Cortés, A. The human microbiome in clinical translation: From bench to bedside. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1632435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canon, W.B. The Wisdom of the Body; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- McEwen, B.S. Stress, adaptation, and disease. Allostasis and allostatic load. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1998, 840, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S.; Stellar, E. Stress and the individual. Mechanisms leading to disease. Arch. Intern. Med. 1993, 153, 2093–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S. Allostasis and allostatic load: Implications for neuropsychopharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacol. Off. Publ. Am. Coll. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2000, 22, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cifuentes, M.; Verdejo, H.E.; Castro, P.F.; Corvalan, A.H.; Ferreccio, C.; Quest, A.F.G.; Kogan, M.J.; Lavandero, S. Low-Grade Chronic Inflammation: A Shared Mechanism for Chronic Diseases. Physiology 2025, 40, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubert, C.; Kong, G.; Renoir, T.; Hannan, A.J. Exercise, diet and stress as modulators of gut microbiota: Implications for neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 134, 104621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.R.; Kennedy, P.J.; Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G.; Clarke, G.; Hyland, N.P. Breaking down the barriers: The gut microbiome, intestinal permeability and stress-related psychiatric disorders. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollins, S.L.; Hodgson, D.M. Stress, microbiota, and immunity. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2019, 28, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, S.J.; Uhlig, F.; Wilmes, L.; Sanchez-Diaz, P.; Gheorghe, C.E.; Goodson, M.S.; Kelley-Loughnane, N.; Hyland, N.P.; Cryan, J.F.; Clarke, G. The impact of acute and chronic stress on gastrointestinal physiology and function: A microbiota-gut-brain axis perspective. J. Physiol. 2023, 601, 4491–4538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofani, G.S.S.; Leigh, S.J.; Gheorghe, C.E.; Bastiaanssen, T.F.S.; Wilmes, L.; Sen, P.; Clarke, G.; Cryan, J.F. Gut microbiota regulates stress responsivity via the circadian system. Cell Metab. 2025, 37, 138–153 e135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Lauber, C.L.; Costello, E.K.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Gonzalez, A.; Stombaugh, J.; Knights, D.; Gajer, P.; Ravel, J.; Fierer, N.; et al. Moving pictures of the human microbiome. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubier, J.A.; Chesler, E.J.; Weinstock, G.M. Host genetic control of gut microbiome composition. Mamm. Genome Off. J. Int. Mamm. Genome Soc. 2021, 32, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.A.; Bacigalupe, R.; Wang, J.; Rühlemann, M.C.; Tito, R.Y.; Falony, G.; Joossens, M.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Henckaerts, L.; Rymenans, L.; et al. Genome-wide associations of human gut microbiome variation and implications for causal inference analyses. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 1079–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, D.; Weissbrod, O.; Barkan, E.; Kurilshikov, A.; Korem, T.; Zeevi, D.; Costea, P.I.; Godneva, A.; Kalka, I.N.; Bar, N.; et al. Environment dominates over host genetics in shaping human gut microbiota. Nature 2018, 555, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zmora, N.; Suez, J.; Elinav, E. You are what you eat: Diet, health and the gut microbiota. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abel, L.; Dessein, A.J. The impact of host genetics on susceptibility to human infectious diseases. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1997, 9, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horby, P.; Nguyen, N.Y.; Dunstan, S.J.; Baillie, J.K. The role of host genetics in susceptibility to influenza: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelemanović, A.; Ćatipović Ardalić, T.; Pribisalić, A.; Hayward, C.; Kolčić, I.; Polašek, O. Genome-Wide Meta-Analysis Identifies Multiple Novel Rare Variants to Predict Common Human Infectious Diseases Risk. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patarčić, I.; Gelemanović, A.; Kirin, M.; Kolčić, I.; Theodoratou, E.; Baillie, K.J.; de Jong, M.D.; Rudan, I.; Campbell, H.; Polašek, O. The role of host genetic factors in respiratory tract infectious diseases: Systematic review, meta-analyses and field synopsis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nibbering, B.; Gerding, D.N.; Kuijper, E.J.; Zwittink, R.D.; Smits, W.K. Host Immune Responses to Clostridioides difficile: Toxins and Beyond. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 804949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Mehrotra, D.V.; Dorr, M.B.; Zeng, Z.; Li, J.; Xu, X.; Nickle, D.; Holzinger, E.R.; Chhibber, A.; Wilcox, M.H.; et al. Genetic Association Reveals Protection against Recurrence of Clostridium difficile Infection with Bezlotoxumab Treatment. mSphere 2020, 5, e00232-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.K.J.; Đapa, T.; Chan, I.Y.L.; MacCreath, T.O.; Slater, R.; Unnikrishnan, M. Regulatory Role of Anti-Sigma Factor RsbW in Clostridioides difficile Stress Response, Persistence, and Infection. J. Bacteriol. 2023, 205, e0046622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.J.; Lauber, C.; Costello, E.K.; Lozupone, C.A.; Humphrey, G.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Caporaso, J.G.; Knights, D.; Clemente, J.C.; Nakielny, S.; et al. Cohabiting family members share microbiota with one another and with their dogs. eLife 2013, 2, e00458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Krajmalnik-Brown, R.; DiBaise, J.K.; Maldonado, J.; Guest, M.A.; Todd, M.; Langer, S.L. Relationship Functioning and Gut Microbiota Composition among Older Adult Couples. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurj, A.L.; Wen, W.; Li, H.L.; Zheng, W.; Yang, G.; Xiang, Y.B.; Gao, Y.T.; Shu, X.O. Spousal correlations for lifestyle factors and selected diseases in Chinese couples. Ann. Epidemiol. 2006, 16, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilchez-Vargas, R.; Skieceviciene, J.; Lehr, K.; Varkalaite, G.; Thon, C.; Urba, M.; Morkūnas, E.; Kucinskas, L.; Bauraite, K.; Schanze, D.; et al. Gut microbial similarity in twins is driven by shared environment and aging. EBioMedicine 2022, 79, 104011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.C.; Kang, D.R.; Choi, K.S.; Nam, C.M.; Thomas, G.N.; Suh, I. Spousal concordance of metabolic syndrome in 3141 Korean couples: A nationwide survey. Ann. Epidemiol. 2006, 16, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuda, T.; Miyazaki, T.; Sakuragi, S.; Moriguchi, J.; Tachibana, H.; Ohashi, F.; Ikeda, M. Significant but weak spousal concordance of metabolic syndrome components in Japanese couples. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2014, 19, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaya, N.; Nakaya, K.; Tsuchiya, N.; Sone, T.; Kogure, M.; Hatanaka, R.; Kanno, I.; Metoki, H.; Obara, T.; Ishikuro, M.; et al. Similarities in cardiometabolic risk factors among random male-female pairs: A large observational study in Japan. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K. Concordance of Characteristics and Metabolic Syndrome in Couples: Insights from a National Survey. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2024, 22, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brieger, L.; Schramm, S.; Schmidt, B.; Roggenbuck, U.; Erbel, R.; Stang, A.; Kowall, B. Aggregation of type-2 diabetes, prediabetes, and metabolic syndrome in German couples. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, A.; Rahme, E.; Dasgupta, K. Spousal diabetes as a diabetes risk factor: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.Y.; Liu, C.S.; Lung, C.H.; Yang, Y.T.; Lin, M.H. Investigating spousal concordance of diabetes through statistical analysis and data mining. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman-Retana, O.; Brinkhues, S.; Hulman, A.; Stehouwer, C.D.A.; Dukers-Muijrers, N.; Simmons, R.K.; Bosma, H.; Eussen, S.; Koster, A.; Dagnelie, P.; et al. Spousal concordance in pathophysiological markers and risk factors for type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional analysis of The Maastricht Study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2021, 9, e001879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Steenbergen, T.J.; Petit, M.D.; Scholte, L.H.; van der Velden, U.; de Graaff, J. Transmission of Porphyromonas gingivalis between spouses. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1993, 20, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asikainen, S.; Chen, C.; Alaluusua, S.; Slots, J. Can one acquire periodontal bacteria and periodontitis from a family member? J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1997, 128, 1263–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, H.; Ishihara, K.; Nakagawa, T.; Yamada, S.; Okuda, K. Relationship between transmission of Porphyromonas gingivalis and fimA type in spouses. J. Periodontol. 2003, 74, 1355–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Winkelhoff, A.J.; Boutaga, K. Transmission of periodontal bacteria and models of infection. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2005, 32, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Troil-Lindén, B.; Alaluusua, S.; Wolf, J.; Jousimies-Somer, H.; Torppa, J.; Asikainen, S. Periodontitis patient and the spouse: Periodontal bacteria before and after treatment. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1997, 24, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenstein, G.; Lamster, I. Bacterial transmission in periodontal diseases: A critical review. J. Periodontol. 1997, 68, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martelli, F.S.; Mengoni, A.; Martelli, M.; Rosati, C.; Fanti, E. Comparison of periodontal microbiological patterns in Italian spouses. Ig. Sanita Pubblica 2012, 68, 589–599. [Google Scholar]

- Rastmanesh, R.; Vellingiri, B.; Isacco, C.G.; Sadeghinejad, A.; Daghnall, N. Oral microbiota transmission partially mediates depression and anxiety in newlywed couples. Explor. Res. Hypothesis Med. 2025, 10, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laharie, D.; Debeugny, S.; Peeters, M.; Van Gossum, A.; Gower-Rousseau, C.; Bélaïche, J.; Fiasse, R.; Dupas, J.L.; Lerebours, E.; Piotte, S.; et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in spouses and their offspring. Gastroenterology 2001, 120, 816–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Santos, M.P.; Frias-Gomes, C.; Oliveira, A.; Sabino, J.; Mañosa, M.; Ellul, P.; Sampaio, A.; Avedano, L.; Leone, S.; Colombel, J.F.; et al. Conjugal inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and European survey. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2021, 34, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, M.; Devesa, F.; Pareja, V.; Ferrando, M.J.; Ortuño, J.; Borghol, A. Development of inflammatory bowel disease in a husband and wife. Gastroenterol. Y Hepatol. 2002, 25, 244–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafillidis, J.K.; Spyropoulos, C.; Rentis, A.; Vagianos, K. Development of Crohn’s disease in husband and wife: The role of major psychological stress. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2014, 27, 433–434. [Google Scholar]

- Comes, M.C.; Gower-Rousseau, C.; Colombel, J.F.; Belaïche, J.; Van Kruiningen, H.J.; Nuttens, M.C.; Cortot, A. Inflammatory bowel disease in married couples: 10 cases in Nord Pas de Calais region of France and Liège county of Belgium. Gut 1994, 35, 1316–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, C.L.; Arnott, I.D. What is the risk that a child will develop inflammatory bowel disease if 1 or both parents have IBD? Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2008, 14, S22–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.P.C.; Gomes, C.; Torres, J. Familial and ethnic risk in inflammatory bowel disease. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2018, 31, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, B.J.; Park, J.H.; Hwang, S.W.; Yang, D.H.; Ye, B.D.; Byeon, J.S.; Myung, S.J.; Yang, S.K.; et al. The Clinical Features of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Patients with Obesity. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 2021, 9981482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.; Gomes, C.; Jensen, C.B.; Agrawal, M.; Ribeiro-Mourão, F.; Jess, T.; Colombel, J.F.; Allin, K.H.; Burisch, J. Risk Factors for Developing Inflammatory Bowel Disease Within and Across Families with a Family History of IBD. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2023, 17, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGovern, D.P.; Kugathasan, S.; Cho, J.H. Genetics of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology 2015, 149, 1163–1176.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jans, D.; Cleynen, I. The genetics of non-monogenic IBD. Hum. Genet. 2023, 142, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehme, M.; Guzzetta, K.E.; Wasén, C.; Cox, L.M. The gut microbiota is an emerging target for improving brain health during ageing. Gut Microbiome 2023, 4, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyanaraman, B.; Cheng, G.; Hardy, M. Gut microbiome, short-chain fatty acids, alpha-synuclein, neuroinflammation, and ROS/RNS: Relevance to Parkinson’s disease and therapeutic implications. Redox Biol. 2024, 71, 103092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, S.; Savva, G.M.; Bedarf, J.R.; Charles, I.G.; Hildebrand, F.; Narbad, A. Meta-analysis of the Parkinson’s disease gut microbiome suggests alterations linked to intestinal inflammation. NPJ Park. Dis. 2021, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, T.R.; Debelius, J.W.; Thron, T.; Janssen, S.; Shastri, G.G.; Ilhan, Z.E.; Challis, C.; Schretter, C.E.; Rocha, S.; Gradinaru, V.; et al. Gut Microbiota Regulate Motor Deficits and Neuroinflammation in a Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Cell 2016, 167, 1469–1480.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubeda, J.V. Null hypothesis of husband-wife concordance of Parkinson’s disease in 1,000 married couples over age 50 in Spain. Neuroepidemiology 1998, 17, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, C.H.; Halverson, M.; Zhang, N.; Shill, H.A.; Driver-Dunckley, E.; Mehta, S.H.; Atri, A.; Caviness, J.N.; Serrano, G.E.; Shprecher, D.R.; et al. Conjugal Synucleinopathies: A Clinicopathologic Study. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2024, 39, 1212–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, A.W.; Sterling, C.; Racette, B.A. Conjugal Parkinsonism and Parkinson disease: A case series with environmental risk factor analysis. Park. Relat. Disord. 2010, 16, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, A.H.; Ferguson, L.W.; Robinson, C.A.; Guella, I.; Farrer, M.J.; Rajput, A. Conjugal parkinsonism—Clinical, pathology and genetic study. No evidence of person-to-person transmission. Park. Relat. Disord. 2016, 31, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, N.P.; O’Riordan, J.I.; Chataway, J.; Kingsley, D.P.; Miller, D.H.; Clayton, D.; Compston, D.A. Offspring recurrence rates and clinical characteristics of conjugal multiple sclerosis. Lancet 1997, 349, 1587–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schapira, K.; Poskanzer, D.C.; Miller, H. Familial and conjugal multiple sclerosis. Brain 1963, 86, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebers, G.C.; Koopman, W.J.; Hader, W.; Sadovnick, A.D.; Kremenchutzky, M.; Mandalfino, P.; Wingerchuk, D.M.; Baskerville, J.; Rice, G.P. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: A geographically based study: 8: Familial multiple sclerosis. Brain 2000, 123, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebers, G.C.; Yee, I.M.; Sadovnick, A.D.; Duquette, P. Conjugal multiple sclerosis: Population-based prevalence and recurrence risks in offspring. Ann. Neurol. 2000, 48, 927–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitaliano, P.P. An ironic tragedy: Are spouses of persons with dementia at higher risk for dementia than spouses of persons without dementia? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2010, 58, 976–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.W.; Bae, J.B.; Oh, D.J.; Moon, D.G.; Lim, E.; Shin, J.; Kim, B.J.; Lee, D.W.; Kim, J.L.; Jhoo, J.H.; et al. Exploration of Cognitive Outcomes and Risk Factors for Cognitive Decline Shared by Couples. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2139765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagi, E.; Franceschi, C.; Rampelli, S.; Severgnini, M.; Ostan, R.; Turroni, S.; Consolandi, C.; Quercia, S.; Scurti, M.; Monti, D.; et al. Gut Microbiota and Extreme Longevity. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 1480–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, A.; Ostan, R.; Candela, M.; Biagi, E.; Brigidi, P.; Capri, M.; Franceschi, C. Gut microbiota changes in the extreme decades of human life: A focus on centenarians. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, Z.; Sun, G.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yang, R.; Li, C.; Wang, T.; Tan, D.; Qi, S.; Jun, C.; et al. Metagenomics Study Reveals Changes in Gut Microbiota in Centenarians: A Cohort Study of Hainan Centenarians. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Hua, Y.; Zeng, B.; Ning, R.; Li, Y.; Zhao, J. Gut microbiota signatures of longevity. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, R832–R833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herskind, A.M.; McGue, M.; Holm, N.V.; Sørensen, T.I.; Harvald, B.; Vaupel, J.W. The heritability of human longevity: A population-based study of 2872 Danish twin pairs born 1870–1900. Hum. Genet. 1996, 97, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby, J.G.; Wright, K.M.; Rand, K.A.; Kermany, A.; Noto, K.; Curtis, D.; Varner, N.; Garrigan, D.; Slinkov, D.; Dorfman, I.; et al. Estimates of the Heritability of Human Longevity Are Substantially Inflated due to Assortative Mating. Genetics 2018, 210, 1109–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplanis, J.; Gordon, A.; Shor, T.; Weissbrod, O.; Geiger, D.; Wahl, M.; Gershovits, M.; Markus, B.; Sheikh, M.; Gymrek, M.; et al. Quantitative analysis of population-scale family trees with millions of relatives. Science 2018, 360, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlik, K.; Canela-Xandri, O.; Tenesa, A. Indirect assortative mating for human disease and longevity. Heredity 2019, 123, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauricella, S.; Brucchi, F.; Cirocchi, R.; Cassini, D.; Vitellaro, M. The Gut Microbiome in Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer: Distinct Signatures, Targeted Prevention and Therapeutic Strategies. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kottairajan, N.K.; Subha, S.T.; Nasir, Z.M.; Ghani, F.A.; Thilakavathy, K. EBV-Mediated Rewiring of ceRNA Networks in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: Mechanisms, ncRNA Interplay, and Oncogenic Implications. In Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, M.; D’Amico, F.; Fabbrini, M.; Rampelli, S.; Brigidi, P.; Turroni, S. Over-feeding the gut microbiome: A scoping review on health implications and therapeutic perspectives. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 7041–7064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace-Farfaglia, P.; Frazier, H.; Iversen, M.D. Essential Factors for a Healthy Microbiome: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Plećaš, D.; Polašek, O. Can Molecular Pathology Drive Progress in Microbiome Understanding? Lessons from Spousal and Household Studies. J. Mol. Pathol. 2026, 7, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmp7010004

Plećaš D, Polašek O. Can Molecular Pathology Drive Progress in Microbiome Understanding? Lessons from Spousal and Household Studies. Journal of Molecular Pathology. 2026; 7(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmp7010004

Chicago/Turabian StylePlećaš, Doris, and Ozren Polašek. 2026. "Can Molecular Pathology Drive Progress in Microbiome Understanding? Lessons from Spousal and Household Studies" Journal of Molecular Pathology 7, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmp7010004

APA StylePlećaš, D., & Polašek, O. (2026). Can Molecular Pathology Drive Progress in Microbiome Understanding? Lessons from Spousal and Household Studies. Journal of Molecular Pathology, 7(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmp7010004