1. Introduction

In Lu Xun’s 1918 story “Diary of a Madman” (狂人日记), his first vernacular work and a landmark of China’s New Culture Movement, the infamously paranoid protagonist juxtaposes the category of “real humans” (真人) with that of “worms” (虫子). Describing to his brother what he perceives as the cannibalistic society that surrounds them, he presents a theory of social evolution essentially based on the moral prohibition of cannibalism:

Brother, probably all primitive people ate a little human flesh to begin with. Later, because their views altered, some of them stopped and tried so hard to do what was right that they changed into men, into real men. But some are still eating people—just like reptiles. Some have changed into fish, birds, monkeys, and finally men; but those who make no effort to do what’s right are still reptiles. When those who eat men compare themselves to those who don’t, how ashamed they must be. Probably much more ashamed than the reptiles before monkeys.

1

Interestingly, the translators of this passage, Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang, choose to emphasize the moral rather than scientific elements of this evolutionary ladder, translating

chongzi 虫子 as “reptile” instead of its more literal meaning of “insect” or “worm”; Julia Lovell, in her more recent translation with Penguin, retains this translation of “reptile” (

Lu 2009, p. 28). Keeping in mind, however, Lu Xun’s fondness for Thomas Huxley’s

Evolution and Ethics, which he encountered through Yan Fu’s 1898 translation/reinterpretation as

Tianyan Lun (天演论),

2 we might note the way that the madman fuses moral action with a Darwinian notion of evolutionary biology, invoking a hierarchy of lifeforms from worm to monkey. Humans can only become real humans—either at the top of this ladder, or outside of it altogether—by practicing a social morality. In this sense, the separation between human and animal paradoxically falls in line with the traditional Confucian notion whereby the category of human is distinguished from animal through its capacity for moral action. For Lu Xun’s madman, the rejection of cannibalism definitively separates real humans from all other animals, including cannibalistic humans, effectively qualifying the typical evolutionary ladder by making the real human contingent upon a moral element. The madman therefore presents a modern, scientific notion inflected by traditional philosophy, despite his desperate overall plea to break out of the metaphorically cannibalistic tradition of conservative Confucianism.

Worms obviously take center stage in Mao Dun’s short story “Spring Silkworms” (春蚕), written fourteen years after Lu Xun’s “Diary of a Madman.” A reform-minded leftist intellectual like Lu Xun, Mao Dun also juxtaposes humans with worms in a way that paradoxically complicates the relationship between tradition and modernity. Unlike the worms in the madman’s example, however, the worms in Mao Dun’s story do not primarily represent the most “reptilian” form of base, amoral existence, although they do also subtly reveal an anxiety about the human that neither tradition nor modernity seems immediately able to solve. By examining Mao Dun’s story, I first hope to show how the silkworms operate as a metaphor for the villagers, who depend on the silkworms for their livelihood yet are doomed by this very dependence. I propose that Mao Dun’s more extensive use of the worm metaphor raises the same question of Lu Xun’s madman—that of the “real human”—but presents it as a more open and unresolved category.

In 1933, a year after the publication of “Spring Silkworms,” the story was adapted to a film of the same name directed by Cheng Bugao (程步高) for the Mingxing Film Company (明星影片公司). Despite what many contemporary critics described as the film’s lackluster results, I will turn to an examination of it to demonstrate how this visual representation more effectively foregrounds the story’s relationship between human and animal, specifically through the cinematic emphasis on the silkworms, which provides a striking compliment to the villagers’ dehumanization through their alienated labor. Overall, by exploring the story’s ambiguous narrative potential, which David Wang suggests “enhances rather than settles the tension that arises between old and new concepts of technology at a historical juncture” (

Wang 1992, p. 53), I hope to show how the story reveals the helpless, valueless “bare life” to which humans have been reduced in the particular nexus of traditional feudal society, imperialism, and capitalism. By situating these “wormified” humans in what I characterize as the story’s pause in historical materialist time, I aim to demonstrate how the story offers a striking occasion for the potential fundamental questioning of the human, which subtends Mao Dun’s more obvious concerns with politics, ideology, and social reform.

2. Critical Background

Widely regarded as one of Mao Dun’s most representative works, “Spring Silkworms” is the first and most famous of his Village Trilogy, which includes “Autumn Harvest” (秋收) and “Winter Ruin” (残冬). It tells the story of a village of silkworm growers who pour their hearts and souls into raising silkworms, only to find at the end of the season that there are no buyers for their product: The processing plants downriver have all closed, and the villagers are forced to either sell their cocoons elsewhere at a loss or spin them themselves. The story specifically centers on the figure of Old Tongbao (老通宝), a traditional, simple-minded head of the household who struggles against his family’s seemingly inevitable decline by putting his faith in a combination of hard work, superstition, and anti-foreign sentiment. Ultimately, neither his efforts nor those of his fellow family members or villagers are any match for the insurmountable difficulties posed by the overall economic, political, and social conditions in which they find themselves.

Overall, the story stands as a prime example of Mao Dun’s style of critical realism aimed at social reform. “Because the story functions didactically as a kind of sociological diagram,” notes Jian Xu, “it contributes unambiguously to the socialist discourse of nation building” (

Xu 2004, p. 129). Liu Zaifu observes that the work leaves no doubt as to the reasons for the dire situation that Tong Bao and the villagers face: “The bankruptcy of the Chinese countryside was brought about by economic plunder and imperialist military invasions. Feudalistic usury speeded up the impoverishment of the peasantry.” Therefore, the story as a “fictional creation relying on principles of a sociopolitical nature is clearly manifested,” which is “entirely consistent with basic Marxist analyses and evaluations of Chinese society at the time” (

Liu 2021, p. 64).

Despite Mao Dun’s clear ideological commitments and the overall political message of the trilogy, “Spring Silkworms” contains a notable degree of interpretive ambiguity, which has given rise to some debate over the story’s depiction of the peasantry. In A History of Modern Chinese Fiction (1961), C. T. Hsia deems “Spring Silkworms” to be Mao Dun’s best work, arguing that the standard ideological interpretation “hardly explains its strength and appeal.” On the contrary, Hsia proposes that “almost in spite of himself…Mao Dun is celebrating…the dignity of labor”:

Raising silkworms in the traditional Chinese manner is a primitive but exacting form of endeavor that calls for love, patience, and the favor of the Deity; it is almost a form of religious ritual. Mao Dun is able to recapture this religious spirit and to invest the family…with the kind of unquestioned piety habitual with Chinese peasants with their unsparing diligence and unfaltering trust in a beneficent Heaven. Although it is Mao Dun’s articulate intention to discredit this kind of feudal mentality, his loving portrayal of good peasants at their customary tasks transforms the supposed Communist tract into a testament of human dignity.

Several scholars have taken exception to this reading, including Jaroslav Prusek, who contends that Mao Dun’s “portrait of this family is not at all a touching and ‘loving portrayal of good peasants,’” and asserts that Mao Dun shows “the disintegration of this family under the pressure of cruel poverty and, in the end, Old T’ung-pao must admit that his youngest son is right who already grasps that not senseless drudgery, but only the decision to fight for their rights can free the peasantry” (

Prusek 1962, pp. 397–98). Similarly, M. A. Abbas and Tak-wai Wong state that the story depicts raising silkworms as “a form of alienated labor that gives no satisfaction in itself: what sustains the laborer is only the false promise of money at the end” (quoted in

Xu 2004, p. 130).

Others, however, have acknowledged the tension that arises between Mao Dun’s ideological commitments and the clearly more ambiguous (if not “loving”) portrayal of both Old Tongbao and the process of raising the silkworms. Both David Wang and Liu Zaifu, for instance, see Mao Dun’s depiction of the peasants’ travails as neither a celebration of certain traditional values nor a total damnation of them. Instead, they emphasize Mao Dun’s efforts to objectively record a particular historical moment, which is not an allegory itself for the process of historical materialism but rather a realist snapshot of a particular moment within the larger process. Liu notes that the increasingly doomed fate of Old Tongbao “would seem not to fit with historical materialism’s formulation of the temporal order”; however, “only after the ‘old world’ has been destroyed can the ‘new world’ emerge.” Although “history appears to be going backward,” he says, “temporal processes in Mao Dun’s fiction are neither microcosms nor symbols of entire historical processes, but only fragments of them” (

Liu 2021, p. 65). Wang, for his part, observes how in the story,

revolutionary anticipation and reactionary nostalgia…coalesce, reflecting a simultaneous affirmation of inevitable progress and increasing alienation; one in which progress is only apparent because of one’s awareness of ultimate salvation, not from any contemporary evidence.

Taking a step back in this way from more rigidly ideological and allegorical readings, such as the opposing interpretations of Hsia and Prusek, can make way for a more nuanced treatment of the text. In his focus on the story’s depiction of the laboring body, for example, Jian Xu reads Hsia’s commentary not as an ideological framework through which to appreciate the story but rather as an expression of the text’s “excess,” which he describes as “something that stands completely outside of the ideological messages assigned to the story’s theme by both the author and the reader” (

Xu 2004, p. 130). For Xu, Hsia’s observations of the way Tongbao and the villagers struggle through the silkworm rearing do turn out to be “lovable traits” that show the “dignity” of their work. According to Xu, the “unquestioned piety” that Hsia mentions “puts its faith in nature’s ultimate productiveness and the inevitability of its response to human labor,” and it “comprises an originary—natural, as opposed to cultural—condition of production in which the use-value of the body’s work is in effect guaranteed by ‘Heaven” (

Xu 2004, p. 134).

This “originary” condition of production, which is the human body and its “’natural’ diginity” (

Xu 2004, p. 135), points to another, more basic question I see at the heart of the story: what it means to be human—either in such uncertain, historically situated times or in general. I propose taking Liu’s and Wang’s view of the story as a moment of historical regression within the larger process of historical materialism as a kind of “pause” that can allow for a more fundamental questioning of the human, as well as of the relationship between humans and their work. In this sense I will also attend to the “excess” of the warm, humanistic portrayal of Old Tongbao and the villagers while keeping in mind Mao Dun’s clear criticism of the alienated labor involved in the silkworm raising.

3. Living Like Worms

Many critics note the clear opposition between Old Tongbao, the conservative elder who refuses to raise the foreign strain of silkworms, and the younger generations, represented by both his daughter-in-law, Ah Si’s wife (四大娘), who eventually pushes him to raise one tray of the foreign breed, and his younger son, Ah Duo (多多头), who rejects his father’s superstition and sees that raising silkworms will not offer the family a way out of debt. Of course, Old Tongbao’s superstitions—which include relying on a head of “fateful” garlic (‘命运’ 的大蒜头) to predict the success of the cocoon harvest and forbidding Ah Duo to interact with Lotus (莲花), who might bring them bad luck—are clearly meant to be seen through a May Fourth lens as part of the feudal mindset responsible for China’s difficulties in the modern world. Yet Prusek’s perspective on this oppositional relationship, in which he says only Ah Duo is able to grasp “that not senseless drudgery, but only the decision to fight for their rights can free the peasantry,” seems entirely based on the development of Ah Duo’s character in “Autumn Harvest” and “Winter Ruin.” The Ah Duo of “Spring Silkworms” is notably uncommitted and fatalistic, and there is little to suggest he has experienced any sort of enlightenment or come to any kinds of conclusions.

In fact, in “Spring Silkworms,” father and son turn out to be not so different at all. For Old Tongbao, the problem is cosmological, a combination of the forces of both the natural and supernatural worlds. When he exclaims to himself in the opening paragraphs that, “even the weather’s not what it used to be”

3 (真是天也变了!) (

Mao 2001, pp. 138–39), the implication extends beyond the weather to the notion of a heavenly order through the ambiguity of the word

tian 天 (as well as the indication that it is in addition to the heat Old Tongbao is experiencing). While his understanding of the family’s dire financial straits includes the more rational element of foreign imperialism and political unrest—prices are rising; his domestic breed of silkworms brings in a lower price than the foreign breed; and the silk filatures have been occupied by soldiers anticipating an attack from the Japanese—he also attributes their declining fortunes to the restless ghost of a Taiping rebel killed by his grandfather many years ago. Ah Duo, on the other hand, appears to attribute his family’s problems to the human realm:

It seemed to him there was something eternally wrong in the scheme of human relations; but he couldn’t put his finger on what it was exactly, nor did he know why it should be. In a little while, he forgot about this too.

4

Like his father, however, Ah Duo senses that the situation is both much larger than he can grasp and beyond his control. Earlier in the story, when the family members are waiting for the silkworm eggs to hatch, Ah Duo’s sense of submission to a cruel fate keeps him from sharing in the family’s eagerness: “We’re sure to hatch a good crop, he said, but anyone who thinks we’re going to get rich in this life is out of his head”

5 (

Mao 2001, pp. 174–75). Here we see almost a reversal of positions: Despite his superstitious worldview,

6 Old Tongbao is determined to continue working as hard as he can to get ahead; Ah Duo, however, seems passively resigned to the fact that something is wrong with the larger structure of society and that no amount of effort on his part can change it.

7 Still, he behaves with traditional reverence toward his father and earnestly does as he is told during the intensive period of silkworm rearing. Throughout the entire story, there is nothing to indicate that Ah Duo realizes, as Prusek says, that “only the decision to fight for their rights can free the peasantry.”

The story thus presents an intriguing situation in which the expected dynamic of young progressive overcoming older conservative (as seen in Ba Jin’s

Family, for example, among many other examples of May Fourth literature) does not play out just yet: Only in “Autumn Harvest” do Old Tongbao and Ah Duo choose different paths and definitively break with one another (

Mao 2013a;

Mao n.d.b). History, as far as the characters can tell in “Spring Silkworms,” is not moving forward. Both young and old demonstrate a helpless submission to fate while simultaneously working to survive in their immediate conditions. This seeming suspension of (historical materialist) time exposes the characters as equivalent humans, as neither Old Tongbao nor Ah Duo must necessarily embody certain practical social roles to tell the story of China’s hopeful advancement from feudalism to communism—although this is of course the larger framework in which Mao Dun situates the story. Instead, both are resigned and equally helpless, and neither has an answer. It is in this suspended time that the “excess” description of the family’s (and the village’s) efforts to raise silkworms seems to paradoxically convey a certain sense of dignity in work and a certain comfort in traditional values.

This excess, I propose, instead points to the question of what is human by showing glimmers of humanity in an otherwise dehumanized existence. Of course, any dignity of this work must be taken as part of a larger, doomed situation in which the workers are left with a glut of useless product that is worthless to them unless they can find a wholesale buyer. But even more immediately, the pride they take in their work is demonstrated by the redirection of their humanity away from each other, in the human social realm, and its rechanneling almost exclusively toward the care of the worms. During the period of silkworm incubation, interactions among the villagers themselves nearly cease:

For the time being there were few women’s footprints on the threshing ground or the banks of the little stream. An unofficial “martial law” had been imposed. Even peasants normally on very good terms stopped visiting one another.

8

Things are worse for Lotus, whose family’s silkworms don’t do well; Ah Duo is forbidden to speak to her, and the rest of the villagers do their best to avoid her. More extreme, however, is that even human reproduction is replaced both physically and emotionally with the incubation of the worms, as we see when Ah Si’s wife takes up the task:

She held the five pieces of cloth to which the eggs were adhered against her bare bosom. As if cuddling a nursing infant, she sat absolutely quiet, not daring to stir. At night, she took the five sets to bed with her. Her husband was routed out, and had to share Ah Duo’s bed. The tiny silkworm eggs were very scratchy against her flesh. She felt happy and a little frightened, like the first time she was pregnant and the baby moved inside her. Exactly the same sensation!

9

Furthermore, Old Tongbao’s family forfeits their own sleep and food in the interest of raising the “little treasures” (宝宝), as the silkworms are lovingly called. Old Tongbao spends the entire sum of a loan he secures on mulberry leaves for the silkworms, despite his recognition that “our rice will be finished by the day after tomorrow. What are we going to do?” (

Mao 2001, pp. 168–69).

10 Ah Si’s wife is irritated at the attention he pays to the worms’ health over and above that of the family’s: “We’ll have a lot of leaves left over, just like last year!” she warns, before bluntly stating, “All I know is with rice we can eat, without it we’ll go hungry!” (

Mao 2001, pp. 168–69).

11The family’s earnest devotion to the silkworms, putting forth their best efforts in the face of all but certain disaster, may evoke a certain sympathy among readers. Yet it is quite clear that the family is paradoxically living for the worms, pinning all of their hopes on this ill-fated venture. What began as a rational means of continuing or even improving their own survival has become, in the face of their current geopolitical circumstances, a pointless and futile exercise that has ludicrously led them to focus on tending to the lives of these useless worms over and above their own most basic needs. Industrialization and international trade have led them to devote themselves to producing as many cocoons as possible, which depends on their large-scale processing in the silk filatures and the demands of the global market. The hiccup in the modern industrial economic system, around which the villagers have come to construct their productive lives, reveals how alienated they have become from the product of their labor: While they suffer from inadequate food and clothing, they have successfully produced a glut of silkworm cocoons for which they have no practical need and which far exceeds their capacity to process. At the end of the story, we learn of the particular problem their efforts have resulted in:

But the villagers had to think of something. The cocoons would spoil if kept too long. They either had to sell them or remove the silk themselves. Several families had already brought out and repaired silk reels they hadn’t used for years. They would first remove the silk from the cocoons and then see about the next step. Old Tongbao wanted to do the same.

“We won’t sell out cocoons; we’ll spin the silk ourselves!” said the old man. “Nobody ever heard of selling cocoons until the foreign devils’ companies started the thing!”

Ah Si’s wife was the first to object. “We’ve got over five hundred catties of cocoons here,” she retorted. “Where are you going to get enough reels?”

12

The villagers can process some of the silk themselves, but only on a premodern, cottage-industry scale. By increasing their production capacity for cocoons to the greatest extent possible, their product can only gain value as part of a much larger industrial capitalist supply chain and global trade.

As a result, the villagers have developed their productive capabilities in a singular, specialized way dependent upon the forces of industrial capitalism. In fact, they have ended up just as helpless as the silkworms themselves, which have evolved over centuries of domestication to rely on humans for their survival.

13 Bombyx mori, known as “the world’s only truly domesticated insect,” have no natural protective defenses and are unable to travel more than a few caterpillar steps in search of food; they instead rear up their heads to wait for more leaves to be provided to them (

Cook 2003). The adult moths, with their grotesquely stunted wings (

Figure 1), are unable to fly, and human intervention is required to facilitate their mating. In short, they have been bred into “very efficient leaves-into-silk machine[s]” that cannot survive on their own (

Cook 2003). Mao Dun captures the helpless reliance of the silkworms in the story:

By the time the old man ordered another thirty loads, and the first ten were delivered, the sturdy “little darlings” had gone hungry for half an hour. Putting forth their pointed little mouths, they swayed from side to side, searching for food. Daughter-in-law’s heart had ached to see them. When the leaves were finally spread in the trays, the silkworm shed at once resounded with a sibilant crunching, so noisy it drowned out conversation.

14

Metaphorically, Old Tongbao’s family and the villagers have become the worms themselves: overspecialized producers completely reliant upon an external technical economic structure. Here in this historical pause, the villagers are all reduced to the same basic level of wormlike existence, elderly conservatives and progressive youths alike: equally subject to an overwhelming economic system and geopolitical formation that is beyond their full understanding, unable to carry on their lives in a self-sufficient manner. They have become completely helpless and entirely dependent on the industrial silk trade, unable to make use of their product outside of this system.

15Dehumanized as worms, the excess description of the villagers’ labor that conveys a sense of dignity can really only point to an ontological excess that is uniformly denied them by their circumstances. It hints toward the humans they are, who they are not yet able to actually be. The loving care and devotion they display toward the silkworms through their labor is perhaps not so much a dignity of work as it is an indication of their humanity, albeit a humanity that can only be expressed as “excess” rather than as the core constitution of the characters themselves.

4. Worms on Film

In early 1931, the Chinese Leftwing Dramatists Association published “the first leftwing collective strategic involvement in cinema”, which included revealing, rather than directly criticizing, social problems by using “‘small-scale cinema’ to record the situations of factory workers and peasantry“ (

Pang 2002, p. 37). This set the stage for the cinematic adaptation of Mao Dun’s critical realism, with “Spring Silkworms” almost immediately being made into a film of the same name. As “the first Chinese film shot according to a complete shooting script,” the film “adopted a documentary approach,” with the director himself recalling “a close match up between the shooting time and the real time frame of silkworm cultivation” (

Wang 2005, p. 43). The result is undeniably boring, and financially the film was a flop. Participants in a 1933 symposium on the adaptation noted that it “failed as a political tool,” complaining that “there was not a single climax in the film” and that “the spectators were not instructed to pay special attention to any parts of the story” (

Pang 2002, p. 46). Some participants attributed the problems to the film’s “overfidelity,” including a “lack of drama and climax, inadequate emphasis on the dire situation of rural bankruptcy, and weak emotional appeal to the audience” (

Wang 2005, p. 43). One participant, Ye Lingfeng, contended that the “solid and serious style” of the film “does not mean to entertain in the first place” (quoted in

Wang 2005, p. 44).

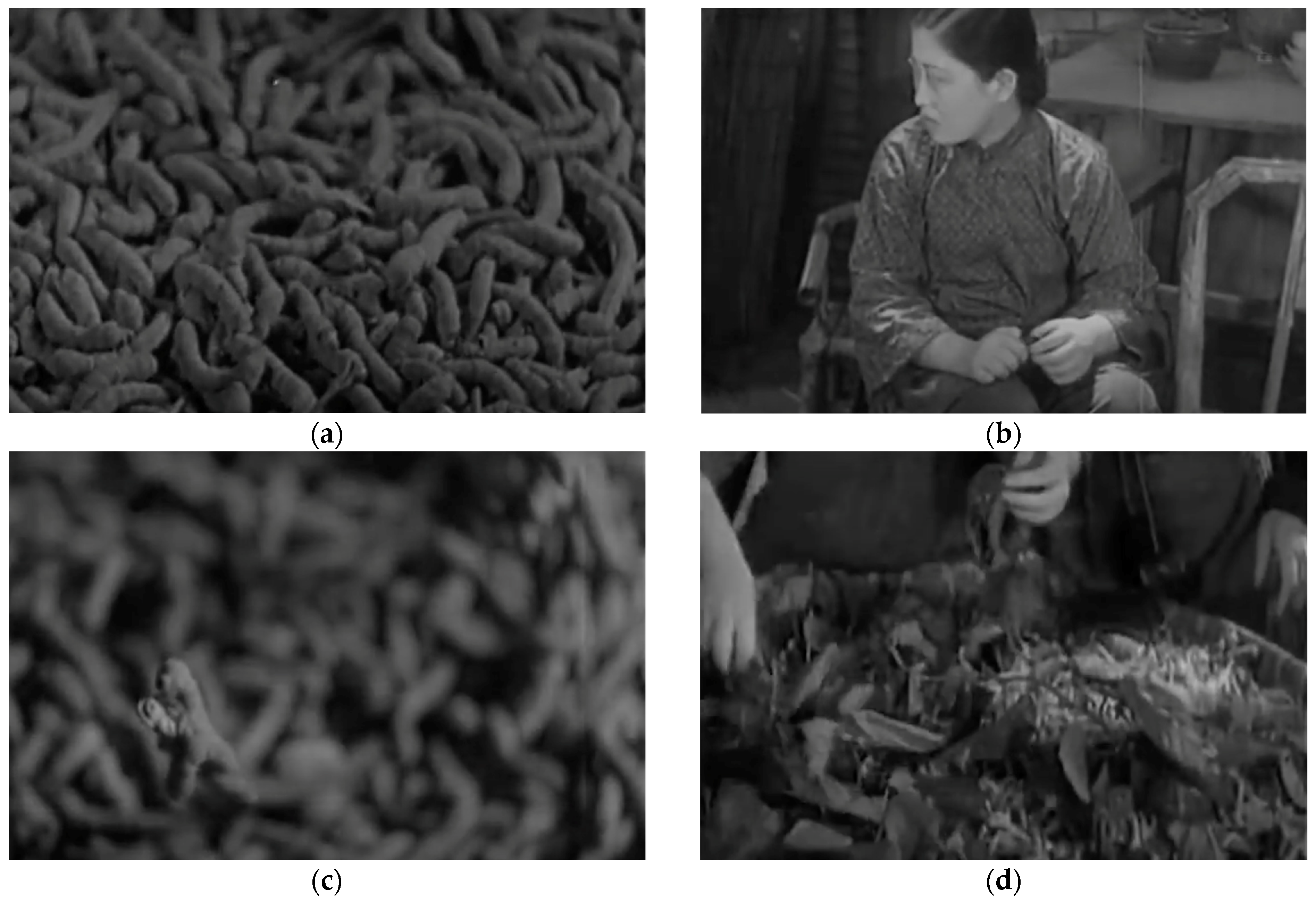

The slow pace and documentary style of the film, however, very effectively emphasize the dehumanization of the story’s characters and their wormlike existence. The film, which is silent and uses intertitles to advance the plot, spends most of its time alternating between close-ups of the silkworms at their various stages of life and medium shots of the humans tending to them (

Figure 2). Few moments in the film depart from this basic rhythm. While the film does offer several plot deviations from Mao Dun’s original story,

16 the most significant difference is perhaps the subtle way that the movement of the plot is mainly dependent upon the silkworms, rather than the humans: The documentation of the silkworms’ lifecycle constitutes the film’s main narrative engine. This is perhaps a result of the particular change Mao Dun’s critical realism has necessarily undergone in its adaptation for the screen: The silkworms, with the real-life documentation of their growth, are the reality, while the human actors constitute the element of fiction.

In their discussion of early Chinese cinema, Barry and Farquhar draw upon Tom Gunning’s notion of the “cinema of attractions”:

the cinema of attractions directly solicits spectator attention, inciting visual curiosity, and supplying pleasure through an exciting spectacle—a unique event, whether fictional or documentary that is of interest in itself.

While Barry and Farquhar focus on the “operatic modes” of Chinese film as related to an early cinema of attractions, which in China included “acrobatics, operas, peep shows, and the many performing arts known as

quyi” (

Berry and Farquhar 2006, p. 50), the heavy visual focus on images of the silkworms is clearly related to the element of spectacle as part of the cinema of attractions. The arch of the silkworm life cycle forms the basic timeline for the film’s narrative, which is enhanced by the human drama: Will the villagers be able to withstand the long “battle” of raising the silkworms, despite their desperate, undernourished, sleep-deprived state? Will the cocoon harvest allow them to pay off their debts and regain any of their property? And yet, as the constant close-up images of the silkworms show, the human drama, diluted and stretched out over an hour and a half, ends up being less interesting and exciting than the images of the silkworms themselves. The spectacle of the silkworms—getting spread onto the trays as baby grubs; getting a meal of mulberry leaves; wiggling and waving their little heads for more food; freshly wrapped up in white, soft-looking cocoons—is far more captivating than the humans tending to them.

In this way, the film affirms the story’s wormification of humans. The novel images of the silkworms going through their life cycle act as a form of spectacle that displaces the human protagonists as the central focus of the film; humans are merely playing a supporting role. This acts as a striking cinematic demonstration of the effects of Marx’s description of alienated labor, in which labor

Does not belong to [the worker’s] essential being; …in his work…he does not affirm himself but denies himself, does not feel content but unhappy, does not develop freely his physical and mental energy but mortifies his body and ruins his mind. …

As a result, therefore, man (the worker) no longer feels himself to be freely active in any but his animal functions—eating, drinking, procreating, or at most in his dwelling and dressing-up, etc.; and in his human functions he no longer feels himself to be anything but animal. What is animal becomes human and what is human becomes animal.

In the story, the villagers’ alienated labor should be clear enough (

Abbas and Wong 1986); as I hope I have demonstrated in the previous section, it results in the metaphorical wormification of humans. In both the story and the film, the humans do nothing but devote themselves to raising the silkworms, to their own physical and spiritual detriment; their constant work has caused their human lives to consist only of the most basic animal functions. The film, however, takes this one step further: The actual silkworms provide more interest as spectacle than do the human actors. The cinematic documentation of the silkworms’ growth, while enhancing the film’s entertainment value as spectacle, also visually establishes the worms as leading actors in their own right. Through a series of close-ups, medium shots, and long shots, we see the worms grow and develop on an intimate, individual level (

Figure 2c) as well as in their larger context. (This is especially true toward the end, when uninterrupted close-ups of the worms beginning to spin their cocoons are shown for nearly a full minute.) In terms of the worms’ visual representation, what is animal has become human. The film’s boring portrayal of the human drama, on the other hand, with its more monotonous visual representation, acts as the cinematic manifestation of how human has become animal: the cinematic effect of the humans’ alienated labor.

The film’s cinematography also establishes a more immediate and perhaps primal connection between human and worm. According to Akira Lippit, on screen, “animals—and their capacity for instinctive, almost telepathic communication—put into question the primacy of human language and consciousness as optimal modes of communication” (

Lippit 2000, p. 2). Because

Spring Silkworms is a silent film, the numerous and prolonged close-ups of the worms carry a heightened communicative power, enabling the audience to commune (if not communicate) with the silkworms. The silent nature of the film denies the human actors the privileged, distinctly human communicative element of speech, thereby enhancing the connection between the audience and the silkworms.

In both the story and the film, as they labor for payment through the industrial processing of silk and its global trade, Old Tongbao and the villagers lose their humanity and are reduced to existing as silkworms in human form, overspecialized and helpless. While contemporary critics of the film may have felt that it “failed as a political tool,” it certainly more poignantly foregrounds the dehumanizing effect of exploitative capitalism, as the human lives portrayed on screen are duller and less interesting than those of the silkworms. This, perhaps, is the real power of Mao Dun’s realism, fully revealed and accentuated by its adaptation to film: humans and worms, both caught in a larger system of economic exploitation, act side by side, playing parallel, commensurate, parts.

5. Conclusions: From Worms to Humans

How do Mao Dun’s wormlike characters regain their humanity? This is an intriguing, and impossible, question that arises in “Spring Silkworms,” and it is one that also points to a hopeful, yet unknowable, human potential should history progress beyond this regressive pause. All of the human roles of the characters, social, political, ideological, etc., have been rendered irrelevant by their singular shared enterprise—raising silkworms—and their shared destiny of debt and hunger (and, consequently, their vulnerability to death). Reduced to living as worms, humans have become the lowest common representation of life in its animal form, the same as in Lu Xun’s madman’s formulation. For the madman, the question was ethical, and as such remained firmly within the bounds of the Confucian philosophical conception of the human. For the villagers, however, the question is different, as they are dehumanized not by their own cannibalistic, cyclical reproduction of a feudal mindset but by their total, helpless submission to the competing forces of feudalism, capitalism, and imperialism. The madman set the figure of the real human in opposition to that of the cannibal, and the difference was a matter of ethics. When Old Tongbao and the villagers are read as dehumanized worms, the same question of the real human arises, but the answer seems less clear. How do Old Tongbao and the villagers ever become “real humans”?

In the broader sense of things, and according to the logic of Mao Dun’s historical materialism, the answer to the villagers’ problems is simple and obvious: The attainment of communism would mean that the workers themselves would own the means of production and distribution, and they would no longer be at the mercy of feudal, imperialist, or capitalist exploitation. Yet this does not really answer the deeper question of what it would mean to be truly human if Old Tongbao and the villagers were to shed their wormhood and (re)gain their humanity. If the combined forces of feudalism, imperialism, and industrial capitalism have reduced the villagers to a base, wormlike existence as “bare life” (

Agamben 1998), then retreating into their old feudal selves (i.e., when they were cannibals and not real humans) is not an option, nor do their current circumstances seem to provide any answers. The real human is merely a future postulate, presumably attainable through the hopeful realization of utopian communism.

This question of what the real human is or could be, as well as its current unknowability, is also implied through the brief appearance of Zhang Caifa (张财发), the father of Old Tongbao’s daughter-in-law. Unlike Old Tongbao and the villagers, who have dehumanized themselves through silkworm rearing, Zhang lives in town and is known as someone always in search of a good time (会寻快活). He is the one who brings the news to Old Tongbao that the silk filatures are closed, and it is his articulation of the current situation that foregrounds the nature of the story’s historical hiatus:

“Tongbao! The cocoons have been gathered, but the doors to the silk filatures are closed up as tight as can be—they won’t be buying anything this year! The eighteen rebels are already in our midst, but Li Shimin hasn’t been born yet—the world is in turmoil! The filatures are closed this year—they’re not doing any business!”

17

By invoking the eighteen rebels and Li Shimin, Zhang draws a historical comparison to the transition from the Sui Dynasty to the Tang. During this transitional period, the “eighteen rebels” rose up against Emperor Yang of Sui, eventually leading to the murder of the emperor and the establishment of the Tang dynasty, which soon came under the rule of Li Shimin, generally considered one of China’s greatest emperors. This passing comment from Zhang Caifa sets “Spring Silkworms” in a different sense of time: Instead of historical materialism in which revolution will bring about a communist mode of production—which is clearly the intended overall sense of time in the complete

Village Trilogy—we see, as David Wang puts it, “the mythic Order of Heaven” which “derives its power from nothing but passive superstitions about heavenly grace” (

Wang 1992, p. 54). As in dynastic transition, the characters in “Spring Silkworms” see themselves as helpless figures at the mercy of the larger forces of history, from which they are entirely separate. The Tang dynasty is known as one of the greatest periods of cultural flourishing in Chinese history, something completely unforeseeable at the dissolution of the Sui. Zhang’s comparison gives the sense that something new and great is on the horizon and that Old Tongbao and the wormlike villagers can only bide their time, momentarily suspended in this period of transition, waiting to see what it will be. Something big—a fundamental change in the structure of human society—must therefore happen before they are able to realize themselves as “real humans.”

Another opportunity opened up by the story’s historical pause is the potential for the suspension of any one dominant discourse, as we see the traditional value system of the villagers confront the logic of capitalism and modernity. Even beyond the text, we see a different construction of the notion of the human according to Lu Xun’s madman, who distinguishes humans from animals in moral rather than economic terms. Clearly there is no settled, authoritative notion of what the human is, and in “Spring Silkworms,” its distinction from the worm must necessarily be questioned. The competing discourses of tradition (i.e., Confucian morality) and modernity (e.g., science, Marxism, capitalism) leave the question open and unsettled.

Although peasant revolution is clearly the preferred means of historical progression in the two stories that follow in the Village Trilogy—Ah Duo leading the starving peasants in revolt “Autumn Harvest” serves as a clear, positive contrast to “Winter Ruin’s” heartless militia supported by the wealthy and the superstitious peasants believing a local twelve-year-old boy is the new emperor—the fundamental question of what constitutes the human remains. In “Winter Ruin,” without revealing a glimpse of promise from peasant revolution (not to mention the attainment of communism), Lotus sees one thing clearly, which is that she has been denied her humanity by both feudal exploitation and by traditional values and superstition:

She hated not being considered “human.” When she had been a slave, the master treated her like a soulless being, an inanimate object, lower than even a cat or a dog. But Lotus knew she had a soul, and this treatment was one of the reasons she hated her former master. […] Unfortunately, half a month after her marriage, her husband fell seriously ill; then their poultry and livestock were stricken by disease. Her reputation was ruined—she was a witch! In the village she was not considered a “human” either! […] [I]t was only when engaged in a hot wrangle or while dallying in amorous pursuits that she was able to feel, at least to some extent—“I’m a human being too.”

18

While the two stories following “Spring Silkworms” point to the more concrete and obvious path forward—peasant revolution—Lotus’ extended anxiety about her humanity in “Winter Ruin” shows that the question of the human is by no means settled. If the political path forward is clear, what it means to be human is not.

The conflicting value systems and ideologies present both inside and outside the text, then, as well as “Spring Silkworm’s” pause in historical materialist time, indicate a space of potential for the very reconceptualization of the human in a way that is as yet unthinkable. In other words, the story indicates the potential to halt what Giorgio Agamben terms the “anthropological machine,” or the constantly erroneous reproduction of the distinction between human and animal, in which “the human is already presupposed every time,” thereby producing “a kind of state of exception, a zone of indeterminacy in which the outside is nothing but the exclusion of an inside,” and vice versa (

Agamben 2004, p. 37).

19Like every space of exception, this zone is, in truth, perfectly empty, and the truly human being who should occur there is only the place of a ceaselessly updated decision in which the caesurae and their rearticulation are always dislocated and displaced anew. What would thus be obtained, however, is neither an animal life nor a human life, but only a life that is separated and excluded from itself—only a bare life.

Both Lu Xun’s cannibals and Mao Dun’s silkworm villagers are humans who are excluded from themselves as humans; they are bare lives, neither human nor animal, lives excluded from themselves by various articulations of this conceptual “anthropological machine.” What is a being that is fully human and not a presupposed interpolation inevitably already set against the exclusion of some part of the human self? In “Spring Silkworms,” Mao Dun gestures toward a hopeful (re)formulation of the human subject, free from the warping powers of various forms of exploitation. The “excess” of the lovable, dignified description of labor has yet to find its true expression in a fully human subject. The significance of the story lies not in any actual answers it offers as to what this might be, but in the space it opens for this ontological questioning necessarily attendant to the more concrete political and ideological goals of the Village Trilogy and Mao Dun’s writing in general.