Consensus Statement: Updated Recommendations for the Interdisciplinary Management of People Living with HIV in Romania

Abstract

Introduction

Methods

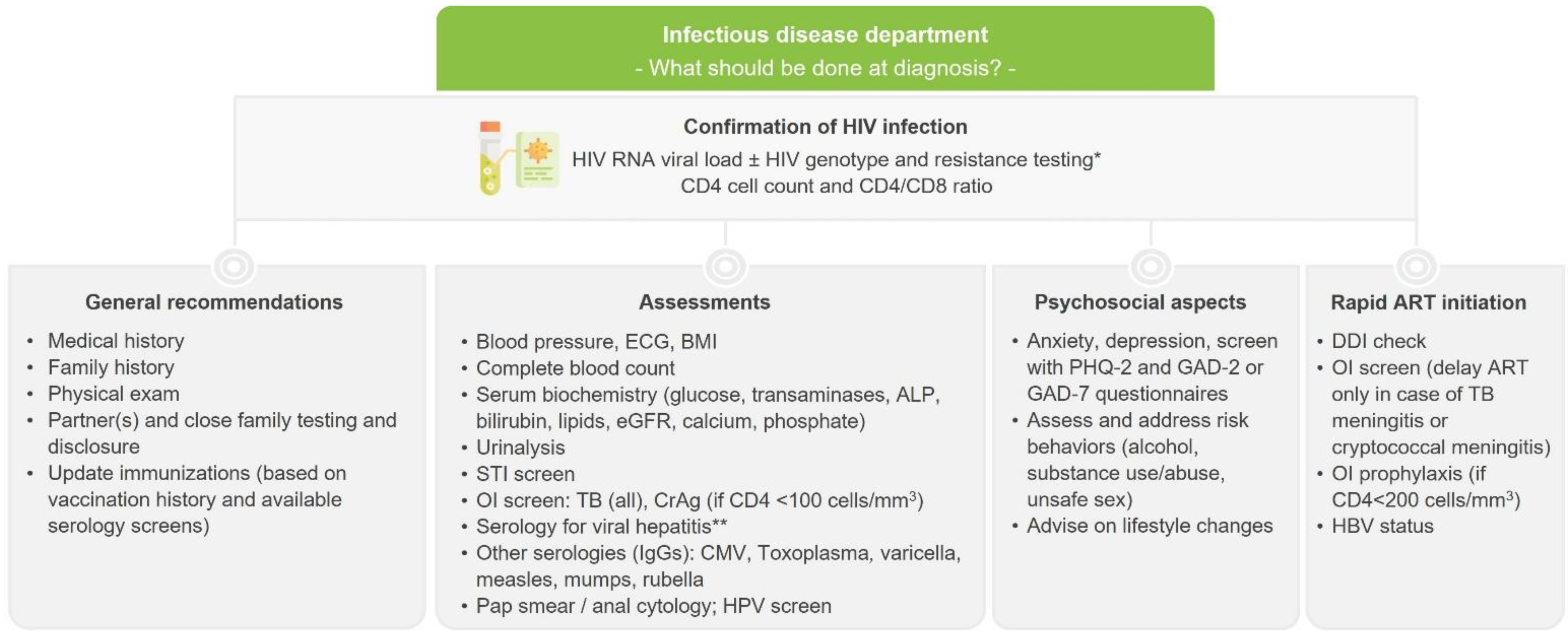

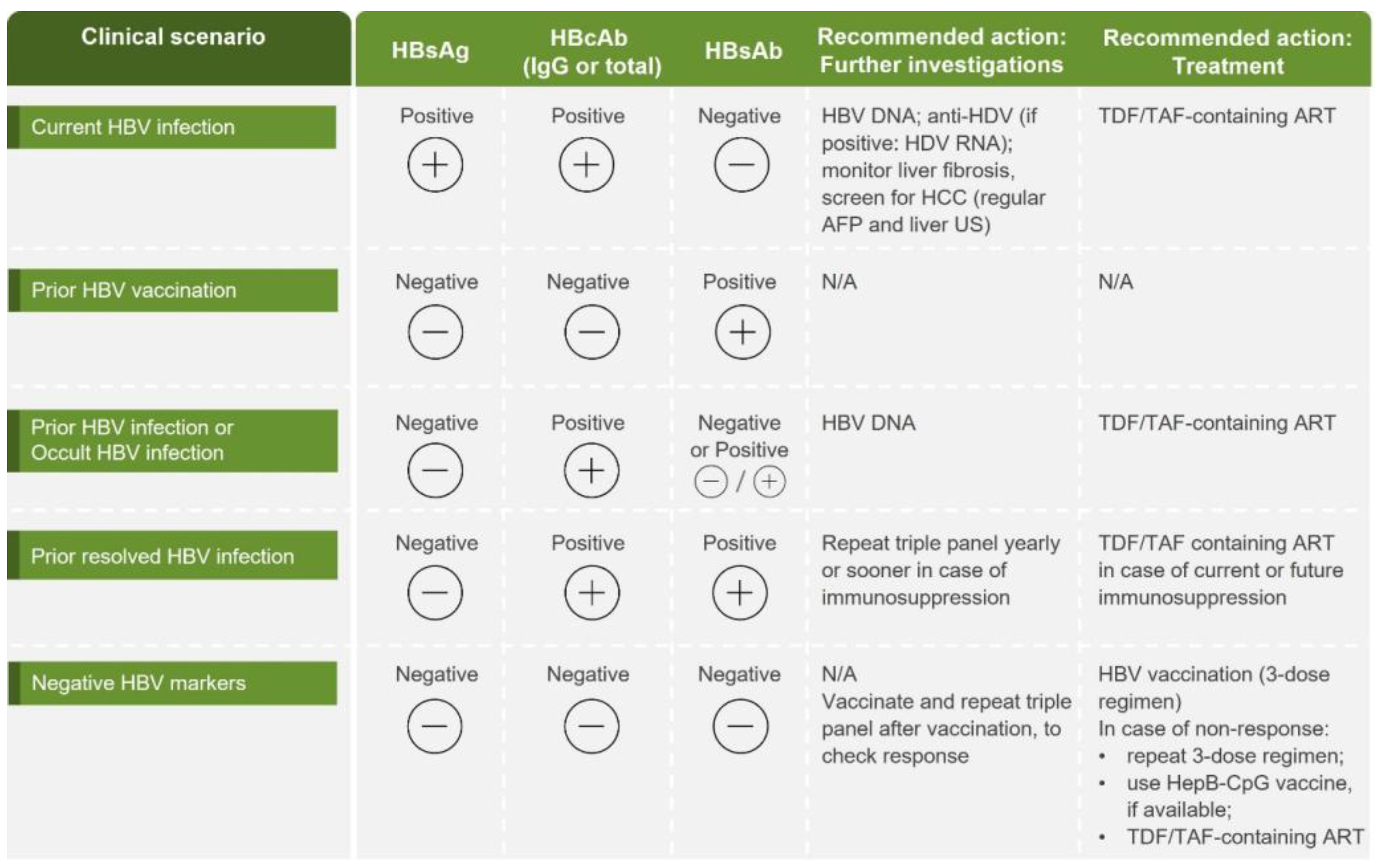

Testing, diagnosis and assessment

Prevention and management of cardiovascular disease

Kidney disease

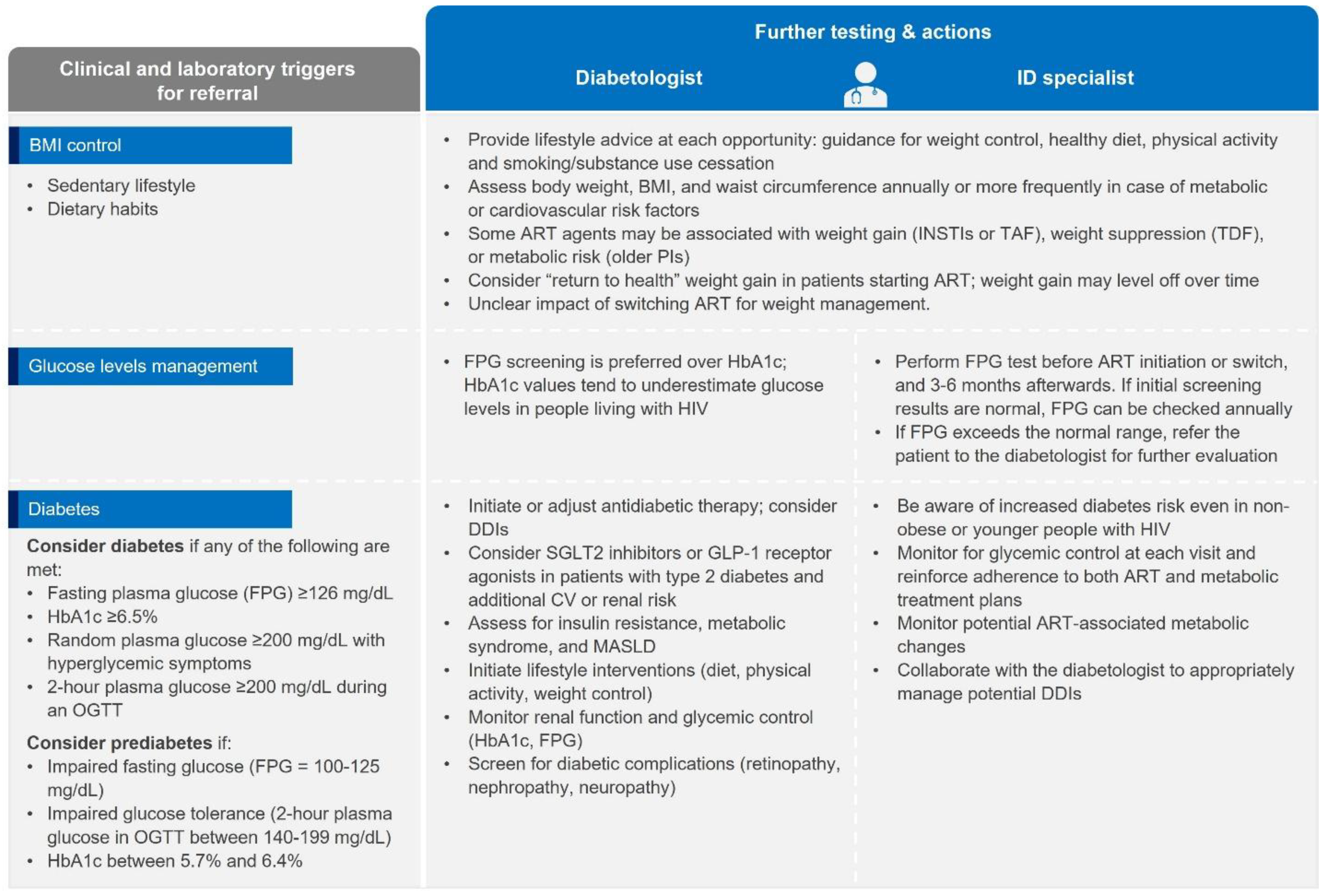

Metabolic disease

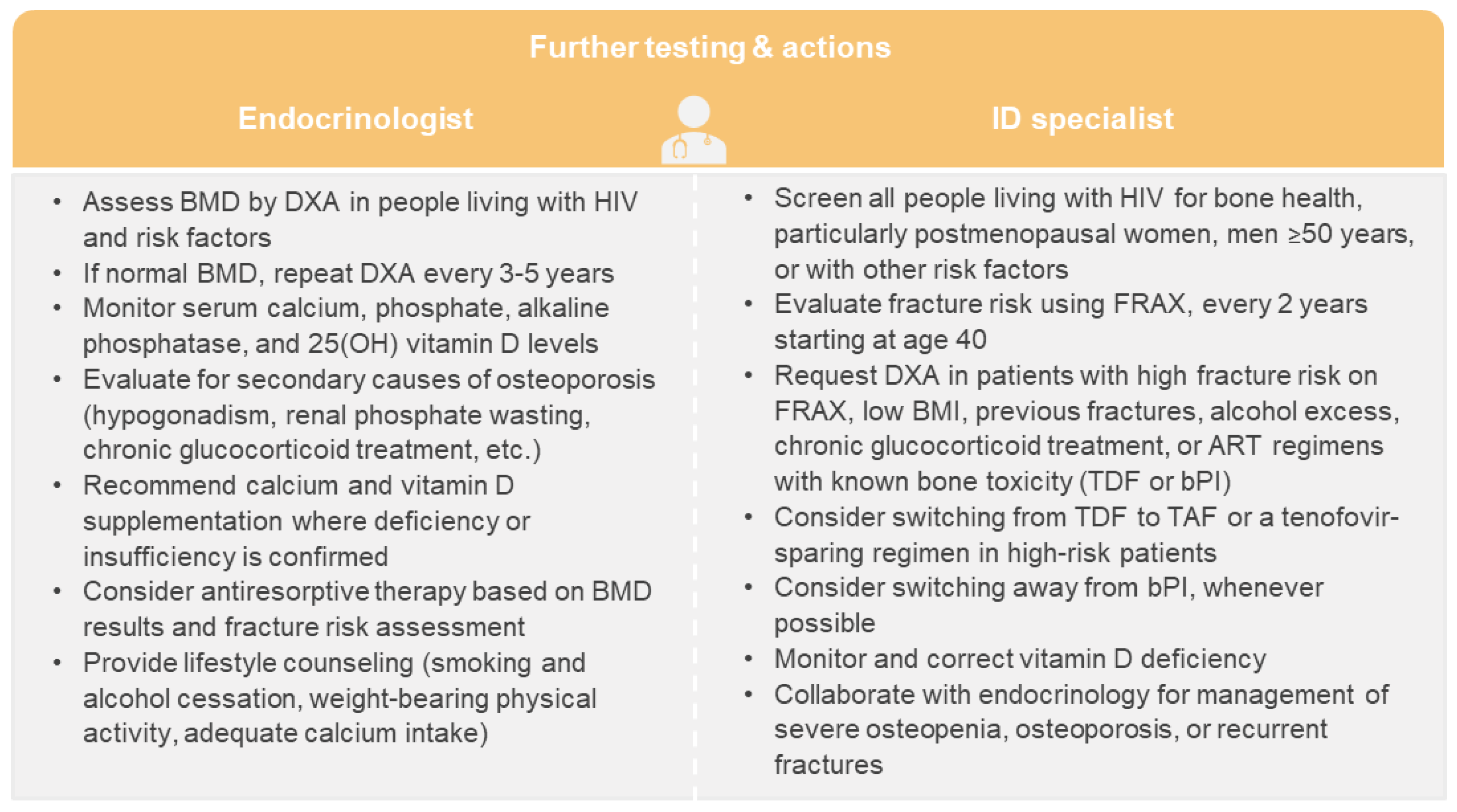

Bone disorders

Preventing vertical transmission of HIV

Opportunistic infections

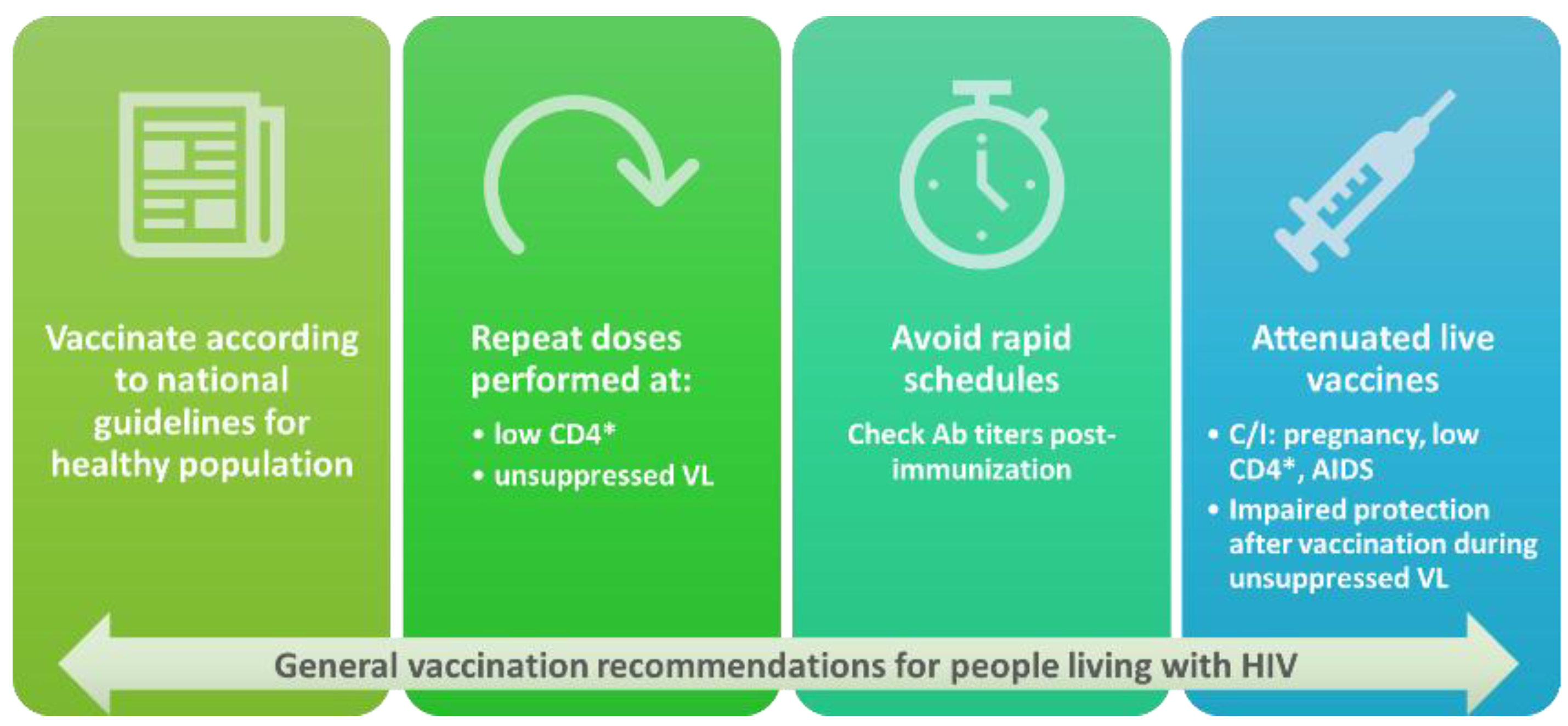

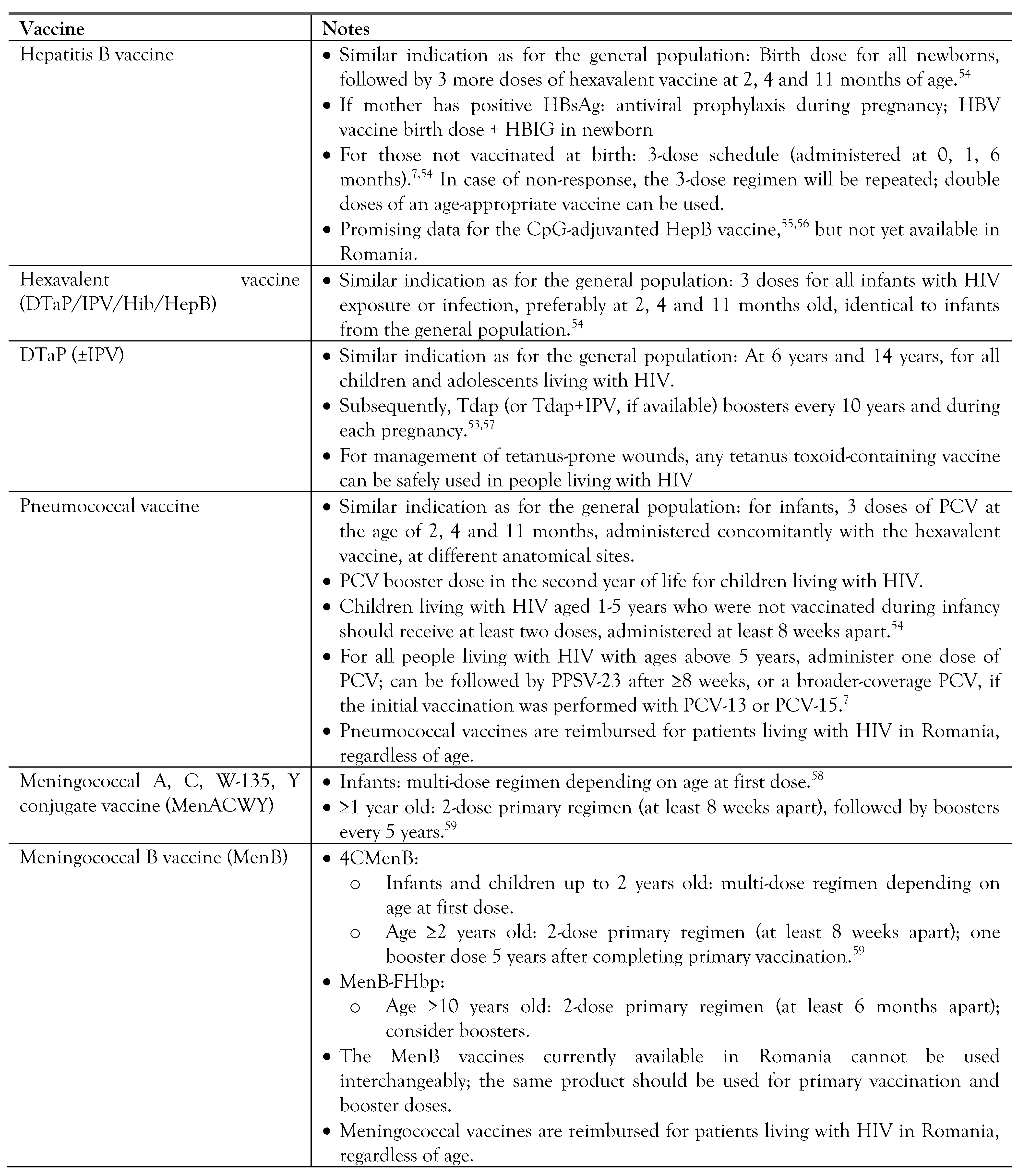

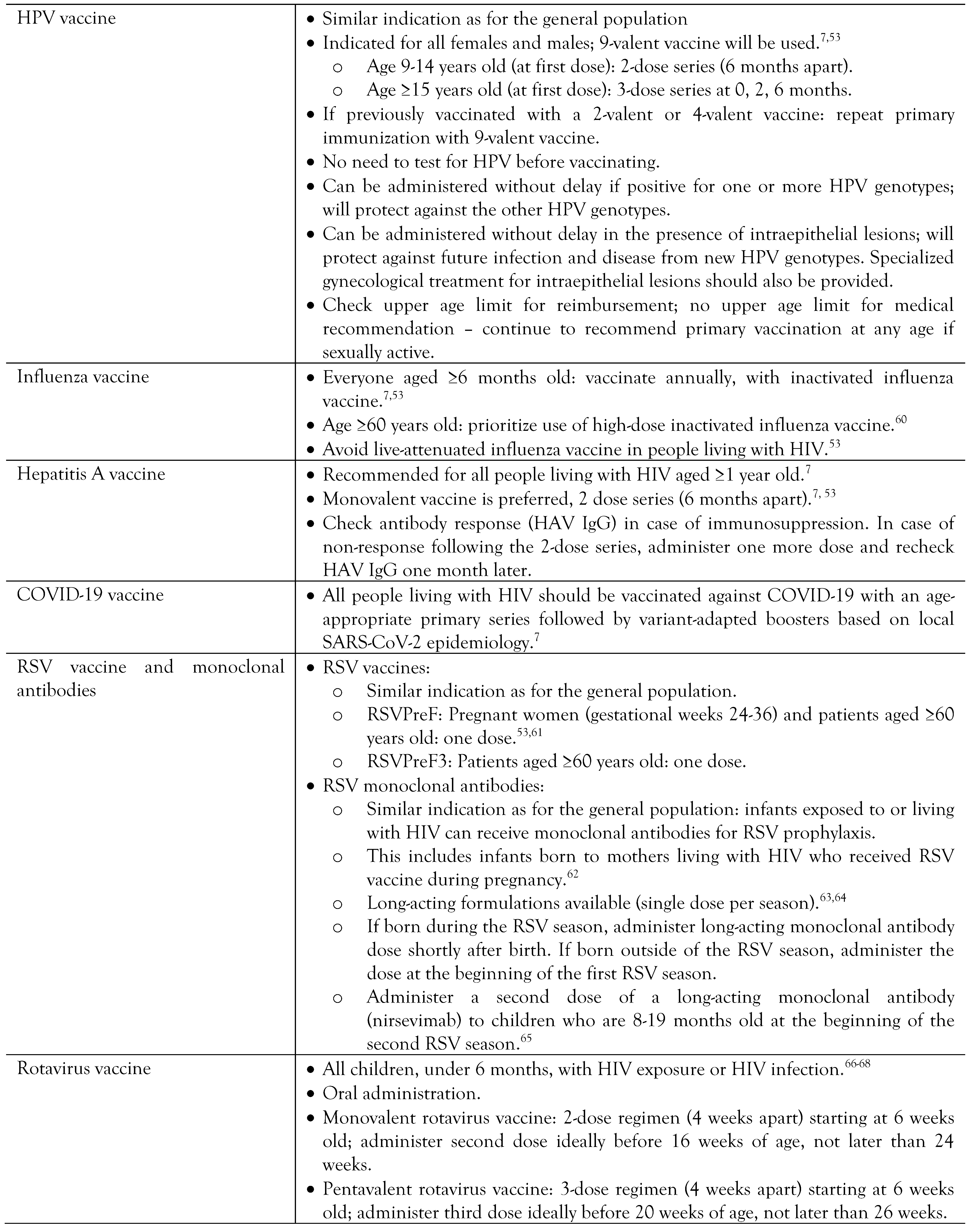

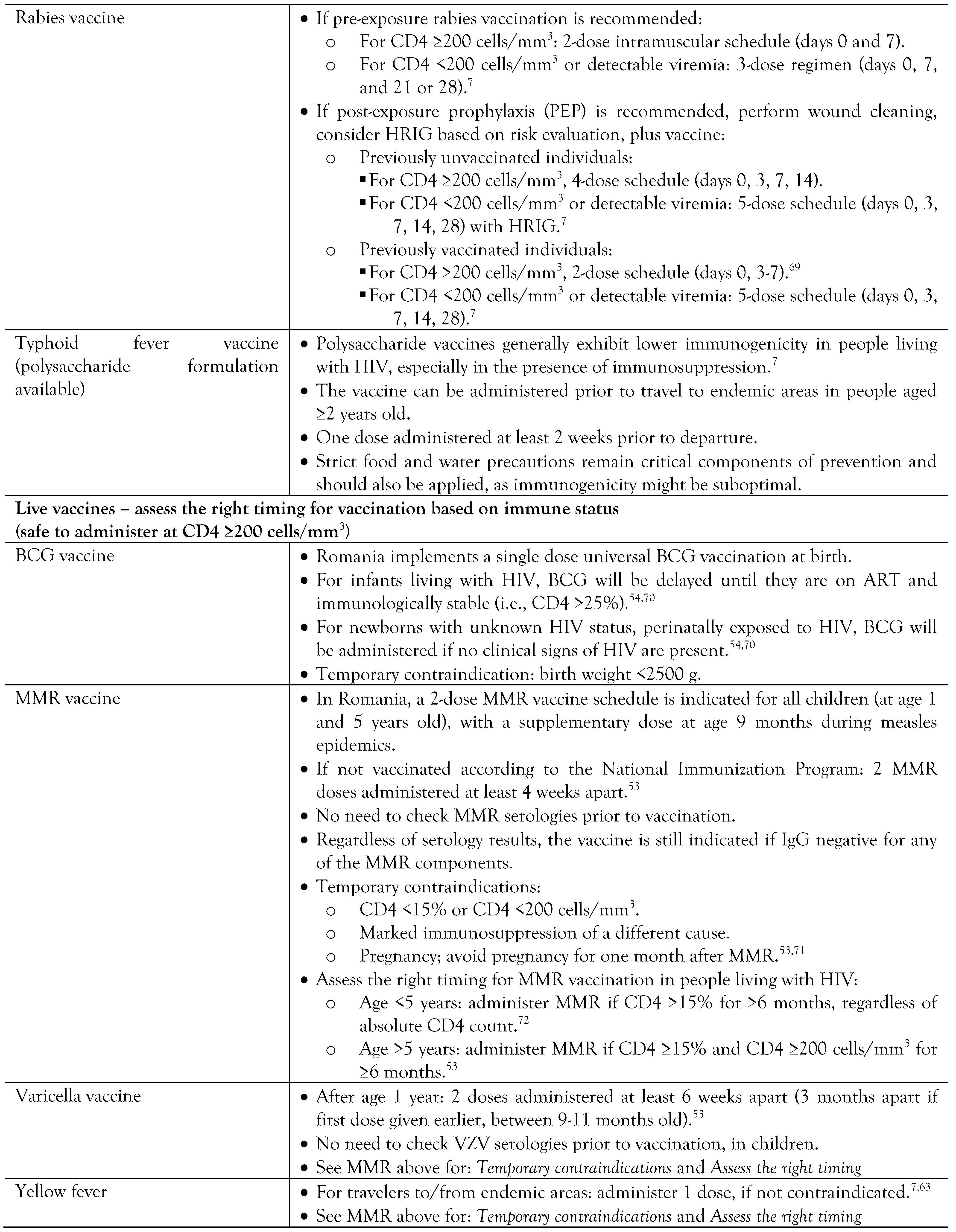

Vaccination in people living with HIV

Quality of life

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- UANIDS (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS). Global HIV & AIDS statistics—Fact sheet. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Vallee, A.; Majerholc, C.; Zucman, D.; et al. Mortality and comorbidities in a nationwide cohort of HIV-infected adults: comparison to a matched non-HIV adults’ cohort, France, 2006–2018. Eur J Public Health. 2024, 34, 879–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Brown, T.T. CROI 2023: Metabolic and other complications of HIV infection. Top Antivir Med. 2023, 31, 538–542. [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon, K.; Nqebelele, U.; Murray, L.; Thomas, T.S.; Mpanya, D.; Tsabedze, N. Cardiac and renal comorbidities in aging people living with HIV. Circ Res. 2024, 134, 1636–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compartimentul pentru Monitorizarea și Evaluarea Infecției HIV/SIDA în România. Evoluția HIV în România, 31 decembrie 2024. Available online: https://www.cnlas.ro/index.php/date-statistice (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. HIV stigma in the healthcare setting. Monitoring implementation of the Dublin Declaration on partnership to fight HIV/AIDS in Europe and Central Asia; ECDC: Stockholm, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European AIDS Clinical Society. EACS Guidelines version 12.1, November 2024. Available online: https://www.eacsociety.org/guidelines/eacs-guidelines/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Streinu-Cercel, A.; Săndulescu, O.; Poiană, C.; et al. Consensus statement on the assessment of comorbidities in people living with HIV in Romania. Germs. 2019, 9, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Getting Tested for HIV. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/testing/index.html (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Maggi, P.; Santoro, C.R.; Nofri, M.; et al. Clusterization of co-morbidities and multi-morbidities among persons living with HIV: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2019, 19, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fichtenbaum, C.J.; Malvestutto, C.D.; Watanabe, M.G.; et al. Effects of antiretrovirals on major adverse cardiovascular events in the REPRIEVE trial: a longitudinal cohort analysis. Lancet HIV. 2025, 12, e496–e505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.S.V.; Stelzle, D.; Lee, K.K.; et al. Global burden of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in people living with HIV: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2018, 138, 1100–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erqou, S.; Lodebo, B.T.; Masri, A.; et al. Cardiac dysfunction among people living with HIV: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JACC Heart Fail. 2019, 7, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, J.; Albuquerque, A.L.A.; Falzon, L. HIV infection as vascular risk: A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017, 12, e0176686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyawo, O.; Brockman, G.; Goldsmith, C.H.; et al. Risk of myocardial infarction among people living with HIV: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2019, 9, e025874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batterham, R.L.; Bedimo, R.J.; Diaz, R.S.; et al. Cardiometabolic health in people with HIV: expert consensus review. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2024, 79, 1218–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinspoon, S.K.; Fitch, K.V.; Zanni, M.V.; et al. Pitavastatin to prevent cardiovascular disease in HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2023, 389, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigna, J.J.; Nansseu, J.R.; Noubiap, J.J. Pulmonary hypertension in the global population of adolescents and adults living with HIV: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 7837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, J.W.; McCarthy, C.P.; Bruno, R.M.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2024, 45, 3912–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, N.E.; Naicker, S. The changing landscape of HIV-associated kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2024, 20, 330–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A.G.; Althoff, K.N.; Jing, Y.; et al. End-stage renal disease among HIV-infected adults in North America. Clin Infect Dis. 2015, 60, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, V.; Berenguer, J. Extrahepatic comorbidities associated with hepatitis C virus in HIV-infected patients. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2015, 10, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mocroft, A.; Neuhaus, J.; Peters, L.; et al. Hepatitis B and C co-infection are independent predictors of progressive kidney disease in HIV-positive, antiretroviral-treated adults. PLoS One. 2012, 7, e40245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2024 Clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, S117–S314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British HIV Association. BHIVA guidelines for the routine investigation and monitoring of adult HIV-1-positive individuals (2019 interim update). Available online: https://bhiva.org/clinical-guideline/monitoring-guidelines/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Gilberti, G.; Tiecco, G.; Marconi, S.; Marullo, M.; Zanini, B.; Quiros-Roldan, E. Weight gain, obesity, and the impact of lifestyle factors among people living with HIV: A systematic review. Obes Rev. 2025, 26, e13908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Brown, T.T. Diabetes in People with HIV. Curr Diab Rep. 2021, 21, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Romieu, A.C.; Garg, S.; Rosenberg, E.S.; Thompson-Paul, A.M.; Skarbinski, J. Is diabetes prevalence higher among HIV-infected individuals compared with the general population? Evidence from MMP and NHANES 2009-2010. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017, 5, e000304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 8. Obesity and weight management for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes: Standards of care in diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care. 2025, 48 (Suppl. 1), S167–S180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 2. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes: Standards of care in diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care. 2025, 48 (Suppl. 1), S27–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 6. Glycemic goals and hypoglycemia: Standards of care in diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care. 2025, 48 (Suppl. 1), S128–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, M.J.; Aroda, V.R.; Collins, B.S.; et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2022. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2022, 45, 2753–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee 5. Facilitating positive health behaviors and well-being to improve health outcomes: Standards of care in diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care. 2025, 48 (Suppl. 1), S86–S127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiau, S.; Broun, E.C.; Arpadi, S.M.; Yin, M.T. Incident fractures in HIV-infected individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2013, 27, 1949–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jespersen, N.A.; Axelsen, F.; Dollerup, J.; Norgaard, M.; Larsen, C.S. The burden of non-communicable diseases and mortality in people living with HIV (PLHIV) in the pre-, early- and late-HAART era. HIV Med. 2021, 22, 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, J.F.; Grund, B.; Roediger, M.; et al. Immediate initiation of antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection accelerates bone loss relative to deferring therapy: Findings from the START bone mineral density substudy, a randomized trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2017, 32, 1945–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.T.; Hoy, J.; Borderi, M.; et al. Recommendations for evaluation and management of bone disease in HIV. Clin Infect Dis. 2015, 60, 1242–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, X.; Liu, F.; Zhang, X.; et al. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation reverses tenofovir-caused bone mineral density loss in people taking ART or PrEP: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Nutr. 2022, 9, 749948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HIVinfo.hih.gov. Preventing perinatal transmission of HIV during pregnancy and childbirth. Available online: https://hivinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv/fact-sheets/preventing-perinatal-transmission-hiv-during-pregnancy-and-childbirth (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- HHS Panel on Treatment of HIV During Pregnancy and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission—A Working Group of the NIH Office of AIDS Research Advisory Council (OARAC). Panel on treatment of HIV during pregnancy and prevention of perinatal transmission. Recommendations for the use of antiretroviral drugs during pregnancy and interventions to reduce perinatal HIV transmission in the United States. Department of Health and Human Services. Available online: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/perinatal (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Penner, J.; Hernstadt, H.; Burns, J.E.; Randell, P.; Lyall, H. Stop, think SCORTCH: rethinking the traditional ‘TORCH’ screen in an era of re-emerging syphilis. Arch Dis Child. 2021, 106, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British HIV Association. BHIVA guidelines on the management of HIV in pregnancy and the postpartum period 2025. Available online: https://bhiva.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/BHIVA-guidelines-on-the-management-of-HIV-in-pregnancy-and-the-postpartum-period.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Rubaihayo, J.; Tumwesigye, N.M.; Konde-Lule, J.; Wamani, H.; Nakku-Joloba, E.; Makumbi, F. Frequency and distribution patterns of opportunistic infections associated with HIV/AIDS in Uganda. BMC Res Notes. 2016, 9, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.E.; Benson, C.; Holmes, K.K.; et al. Guidelines for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009, 58, 1–207. [Google Scholar]

- Gebremichael, G.; Tadele, N.; Gebremedhin, K.B.; Mengistu, D. Opportunistic infections among people living with HIV/AIDS attending antiretroviral therapy clinics in Gedeo Zone, Southern Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2024, 17, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Identifying common opportunistic infections among people with advanced HIV disease. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240084957 (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for diagnosing, preventing and managing cryptococcal disease among adults, adolescents and children living with HIV; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.C.; Harrison, T.S.; Bicanic, T.A.; et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of cryptococcosis: an initiative of the ECMM and ISHAM in cooperation with the ASM. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024, 24, e495–e512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prosty, C.; Hanula, R.; Levin, Y.; Bogoch, I.I.; McDonald, E.G.; Lee, T.C. Revisiting the evidence base for modern-day practice of the treatment of toxoplasmic encephalitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2023, 76, e1302–e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zumla, A.; Chakaya, J.; Centis, R.; et al. Tuberculosis treatment and management--an update on treatment regimens, trials, new drugs, and adjunct therapies. Lancet Respir Med. 2015, 3, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, J.; Bang, N.D.; Imran, D.; et al. Adjunctive dexamethasone for tuberculous meningitis in HIV-positive adults. N Engl J Med. 2023, 389, 1357–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health (Romania). Ordin nr. 3.987/1.156/2023. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/276859 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult immunization schedule by medical condition and other indication. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/imz-schedules/adult-medical-condition.html (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- World Health Organization. Summary of WHO position papers—Recommendations for routine immunization. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/immunization/immunization_schedules/table_1_january_2025_web_english.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Marks, K.M.; Kang, M.; Umbleja, T.; et al. Immunogenicity and safety of hepatitis b virus (HBV) vaccine with a toll-like receptor 9 agonist adjuvant in HBV vaccine-naive people with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2023, 77, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaimova, R.; Fischetti, B.; Cope, R.; Berkowitz, L.; Bakshi, A. Serological response with Heplisav-B(R) in prior hepatitis B vaccine non-responders living with HIV. Vaccine. 2021, 39, 6529–6534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.L.; Tiwari, T.; Moro, P.; et al. Prevention of pertussis, tetanus, and diphtheria with vaccines in the United States: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018, 67, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacNeil, J.R.; Rubin, L.G.; Patton, M.; Ortega-Sanchez, I.R.; Martin, S.W. Recommendations for use of meningococcal conjugate vaccines in HIV-infected persons—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016, 65, 1189–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government—Department of Health and Aged Care. People with medical conditions that increase their risk of invasive meningococcal disease are recommended to receive MenACWY and MenB vaccines. Available online: https://immunisationhandbook.health.gov.au/recommendations/people-with-medical-conditions-that-increase-their-risk-of-invasive-meningococcal-disease-are-recommended-to-receive-menacwy-and-menb-vaccines (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Ministry of Health (Romania). Ordin nr. 5135/1766/2024. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/public/DetaliiDocument/289883 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Dunlevy, H.A.; Johnson, S.C. Routine and special vaccinations in people with HIV. Top Antivir Med. 2024, 32, 411–419. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. RSV immunization guidance for infants and young children. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/hcp/vaccine-clinical-guidance/infants-young-children.html (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Motta, E.; Camacho, L.A.B.; Filippis, A.M.B.; et al. Safety of the yellow fever vaccine in people living with HIV: a longitudinal study exploring post-vaccination viremia and hematological and liver kinetics. Braz J Infect Dis. 2024, 28, 103719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihălțan, F.D.; Ulmeanu, R.; Nemeș, R.M.; Petrea, S.; Streinu-Cercel, A.; Săndulescu, O. Innovative approaches in RSV prevention: The expanding role of monoclonal antibodies in protection for all infants. Germs 2025, 15, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). ACIP evidence to recommendations for use of nirsevimab in children 8-19 months of age at increased risk of severe disease entering their second RSV season. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/acip/evidence-to-recommendations/nirsevimab-season2-rsv-infants-children-etr.html (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Steele, A.D.; Madhi, S.A.; Louw, C.E.; et al. Safety, reactogenicity, and immunogenicity of human rotavirus vaccine RIX4414 in human immunodeficiency virus-positive infants in South Africa. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011, 30, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, L.G.; Levin, M.J.; Ljungman, P.; et al. 2013 IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of the immunocompromised host. Clin Infect Dis. 2014, 58, e44–e100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UK Health Security Agency. Guidance: Rotavirus vaccination programme: Information for healthcare professionals. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/rotavirus-qas-for-healthcare-practitioners/rotavirus-vaccination-programme-information-for-healthcare-professionals (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- British HIV Association. BHIVA guidelines on the use of vaccines in HIV-positive adults 2015. Available online: https://bhiva.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/2015-Vaccination-Guidelines.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Kilapandal Venkatraman, S.M.; Sivanandham, R.; Pandrea, I.; Apetrei, C. BCG vaccination and mother-to-infant transmission of HIV. J Infect Dis. 2020, 222, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geretti AM on behalf of the BHIVA immunisation in adults with HIV guidelines writing group. BHIVA position statement on measles in people living with HIV. Available online: https://bhiva.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/BHIVA-position-statement-on-measles-in-people-living-with-HIV.pdf.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Routine measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/mmr/hcp/recommendations.html (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Ministry of Health (Romania). Plan de vaccinare în contextul răspândirii globale a cazurilor de variola maimuţei, Ordin 2812/2022. Available online: https://lege5.ro/Gratuit/gezdmobyhaydm/plan-de-vaccinare-in-contextul-raspandirii-globale-a-cazurilor-de-variola-maimutei-ordin-2812-2022?dp=gq4tqmjthe4teoa (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- World Health Organization. Integration of mental health and HIV interventions. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240043176 (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Engler, K.; Avallone, F.; Cadri, A.; Lebouche, B. Patient-reported outcome measures in adult HIV care: A rapid scoping review of targeted outcomes and instruments used. HIV Med. 2024, 25, 633–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Duan, X.; Kang, H.; Qu, B. HIV-specific reported outcome measures: Systematic review of psychometric properties. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022, 8, e39015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clinical situation | Serum creatinine (eGFRa) | Complete urinalysisb |

|---|---|---|

| At ART initiation | Yes | Yes |

| No renal risk, not on TDF | Every 6-12 months | Annually |

| On TDF | Every visit | Every visit |

| eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Every 3 months or more often | Every 3 months or more often |

| Comorbidities (HBP, diabetes) | Every 6 months | Every 6-12 months |

|

|

|

|

© GERMS 2025.

Share and Cite

Săndulescu, O.; Streinu-Cercel, A.; Mărdărescu, M.; Oprea, C.; Dorobanţu, M.; Ismail, G.; Reghina, A.D.; Chirilă, O.; Extended Consensus Group; Streinu-Cercel, A. Consensus Statement: Updated Recommendations for the Interdisciplinary Management of People Living with HIV in Romania. Germs 2025, 15, 221-241. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2025.1470

Săndulescu O, Streinu-Cercel A, Mărdărescu M, Oprea C, Dorobanţu M, Ismail G, Reghina AD, Chirilă O, Extended Consensus Group, Streinu-Cercel A. Consensus Statement: Updated Recommendations for the Interdisciplinary Management of People Living with HIV in Romania. Germs. 2025; 15(3):221-241. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2025.1470

Chicago/Turabian StyleSăndulescu, Oana, Anca Streinu-Cercel, Mariana Mărdărescu, Cristiana Oprea, Maria Dorobanţu, Gener Ismail, Aura Diana Reghina, Odette Chirilă, Extended Consensus Group, and Adrian Streinu-Cercel. 2025. "Consensus Statement: Updated Recommendations for the Interdisciplinary Management of People Living with HIV in Romania" Germs 15, no. 3: 221-241. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2025.1470

APA StyleSăndulescu, O., Streinu-Cercel, A., Mărdărescu, M., Oprea, C., Dorobanţu, M., Ismail, G., Reghina, A. D., Chirilă, O., Extended Consensus Group, & Streinu-Cercel, A. (2025). Consensus Statement: Updated Recommendations for the Interdisciplinary Management of People Living with HIV in Romania. Germs, 15(3), 221-241. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2025.1470