Introduction

Hydropneumothorax with a bronchopleural fistula is a rare but severe complication of necrotizing pneumonia. Both are associated with a high morbidity and mortality rate. It may occur secondary to various factors such as thoracentesis, thoracic trauma, malignancy, autoimmune rheumatic diseases, esophagopleural fistula, and infections.[

1] The typical clinical presentation includes sudden onset of unilateral thoracic pain, cough, and dyspnea. Regarding radiological findings, the presence of air-fluid level on chest Xray is an important clue that can be confirmed as a lenticular shape structure, which compresses lung parenchyma on computerized tomography (CT).[

2]

Therapeutic management is challenging since there is little national or international literature on hydropneumothorax. Typically, the approach is determined according to the etiology, the patient’s characteristics, and risk stratification.[

3] The gold standard for conservative treatment remains the chest tube insertion combined with broad-spectrum antibiotics. In case of conservative treatment failure, a surgical approach is needed. Furthermore, the presence of lung necrotic tissue, bronchopleural fistula, and malignancy are predictors of conservative treatment failure; consequently, an early surgical approach is mandatory.[

4]

We present the case of a patient with necrotizing pneumonia caused by multidrugresistant (MDR) Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa complicated by hydropneumothorax and bronchopleural fistula.

Case report

A 76-year-old man, severely frail because of Parkinson’s disease, presented to the emergency department with complaints of fever, productive cough, and dyspnea on exertion for the past two days. No previous history of pulmonary disease was known. On admission, the patient was tachypneic with a respiratory rate of 24 breaths/min and an SpO

2 of 85% in room air. Physical examination revealed crackles in the left lung base but without consolidation on chest Xray. White blood cells were 13,800/μL (85% neutrophils), C-reactive protein was 9.41 mg/dL (10 times higher than the upper normal limit), and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 78 mm/1h.

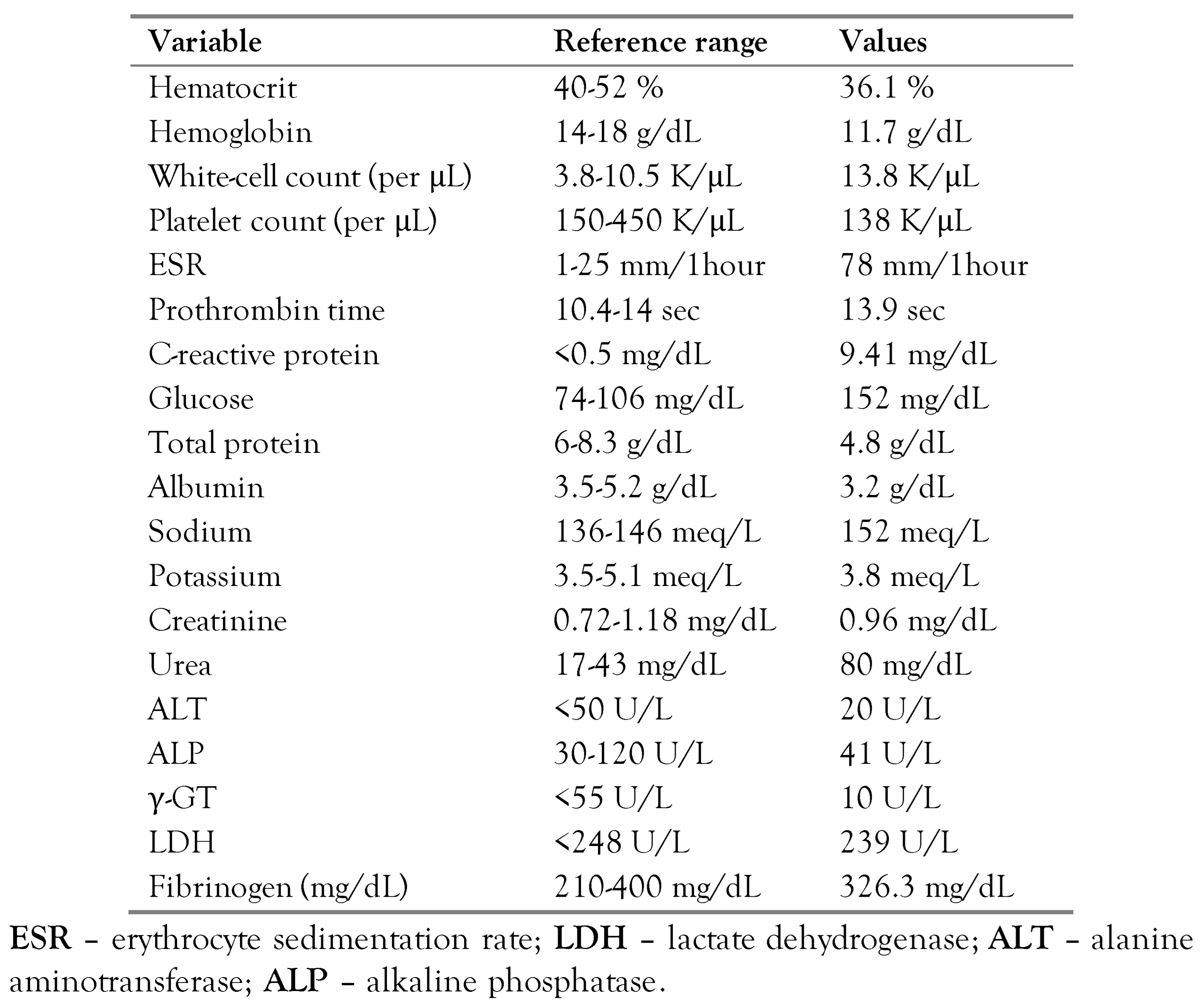

Table 1 shows the results of the laboratory exams on admission. The patient was admitted to the Internal Medicine Department of the University General Hospital of Heraklion, Greece, with a diagnosis of severe communityacquired lower respiratory tract infection. He was treated with supplemental oxygen therapy and intravenous empirical antimicrobial treatment with ampicillin-sulbactam and azithromycin since he had not received antibiotics in the previous three months nor had a history of recent hospitalization.

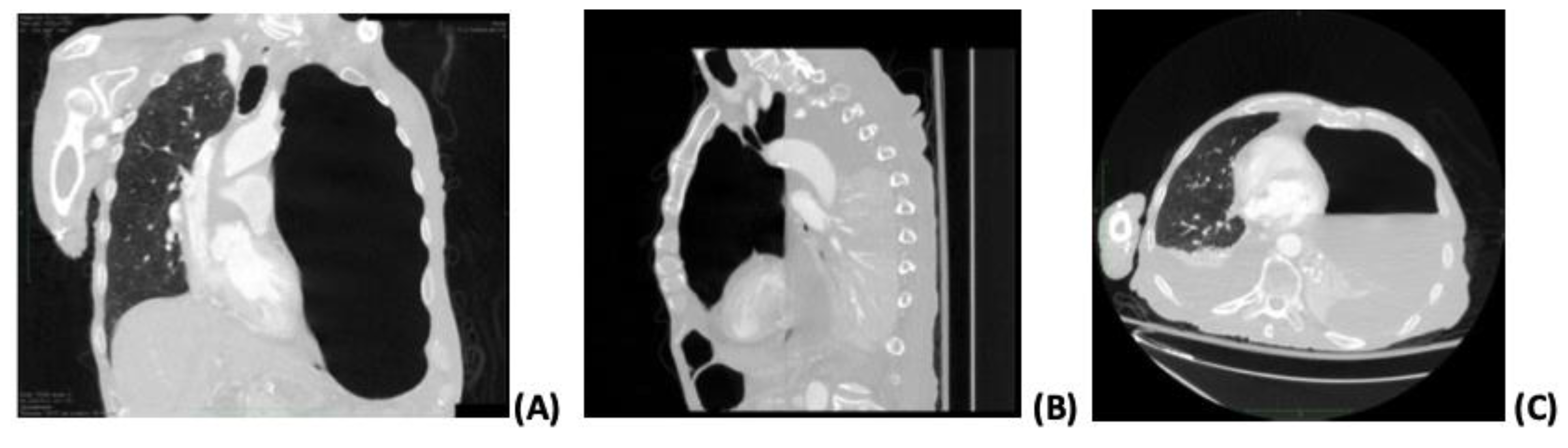

On the sixth day of hospitalization, the patient deteriorated clinically, with a high fever and elevation of inflammation markers on laboratory exams. Blood, urine, and sputum cultures were obtained, with negative results. In addition, antimicrobial treatment was upgraded to piperacillin-tazobactam and linezolid on the same day. A chest X-ray was performed, which showed consolidation in the upper left pulmonary lobe with a gas-fluid level. On the eighth hospital day, a thoracic CT scan confirmed an almost complete left lung collapse due to hydropneumothorax with features suggestive of necrotizing pneumonia and a right mediastinal shift.

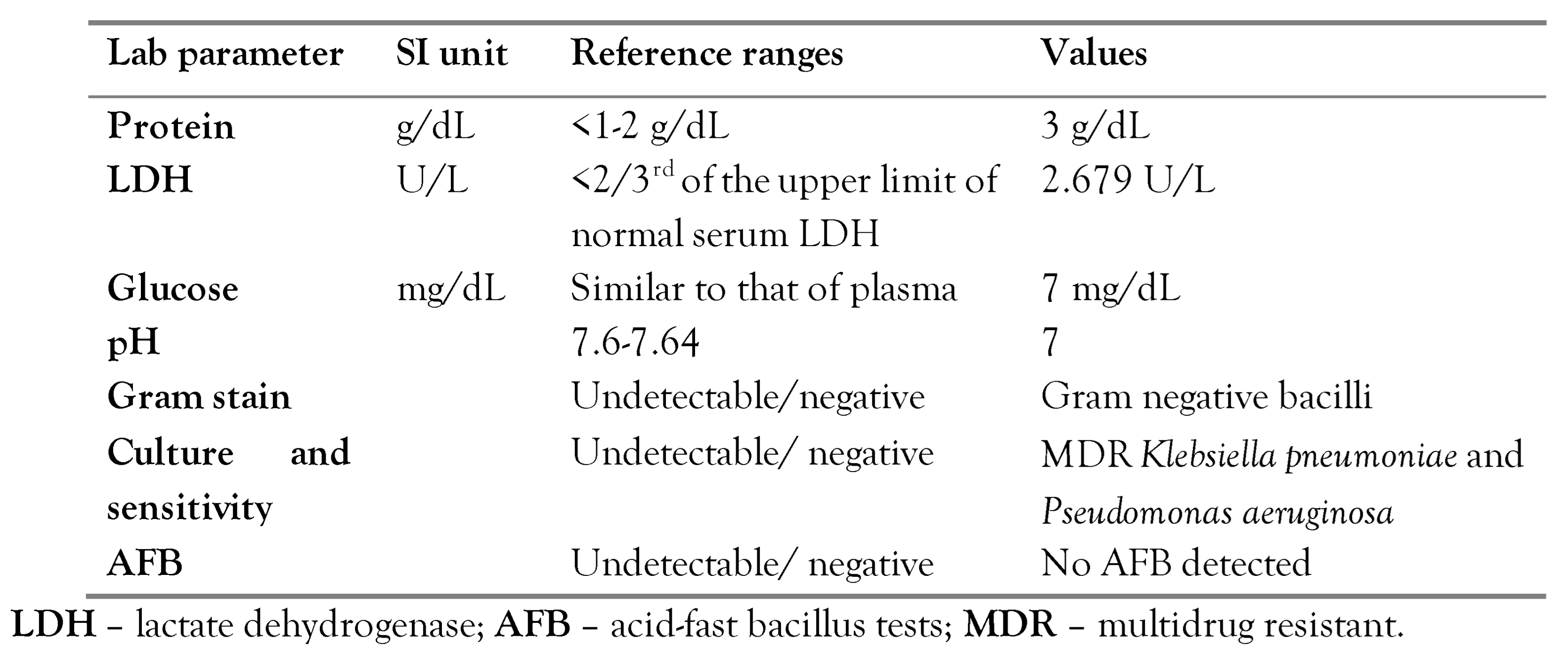

Figure 1 shows the findings of the CT. A chest tube was inserted into the left hemithorax, draining a semi-clear, yellow fluid and air. Diagnostic pleural analysis revealed an exudate effusion with 9.600 cells/μL leukocytes (87% neutrophils), while Gram stain detected Gram-negative bacilli.

Table 2 shows the pleural fluid analysis. On the 16

th hospital day, the pleural fluid culture revealed the growth of a MDR

K. pneumoniae and

P. aeruginosa. Thus, a diagnosis of necrotizing pneumonia complicated by hydropneumothorax was made. Empirical antimicrobial treatment was modified according to the antibiogram, with a combination of piperacillin-tazobactam and levofloxacin to increase the coverage on

P. aeruginosa. This antimicrobial regimen was administered for 12 days in total.

Follow-up was performed by a multidisciplinary team involving several healthcare professionals, such as Infectious diseases specialists, Internists, Pulmonologists, and Thoracic surgeons. Frequent monitoring of lung parenchyma and pleural infusion drainage was performed since the chest tube remained for several days due to significant exudate fluid draining. However, his clinical and radiological condition did not improve substantially, and thoracic surgeons suggested open window thoracotomy. The patient and his siblings denied surgical management due to the high perioperative risk. The possibility of interventional bronchoscopy was also discussed, but due to the need for intubation and aggressive support, a conservative approach was chosen after discussion with the patient’s family. On the 28th hospital day, the patient gradually deteriorated. Another pleural fluid culture and two blood cultures from different venipuncture sites grew MDR Candida parapsilosis. The patient died of septic shock due to candidemia on the 33rd hospital day. The blood culture was drawn within 24 hours before the patient died, thus, the result was available after his death and antifungals could not have been administered.

Discussion

Herein, we presented a case of hydropneumothorax due to necrotizing pneumonia caused by MDR P. aeruginosa and K. pneumoniae in a frail patient without recent antibiotic use or hospitalizations.

Necrotizing pneumonia represents a severe form of community-acquired pneumonia that is characterized by pulmonary inflammation with consolidation, cavitation, and peripheral necrosis of pulmonary tissue. It tends to occur in adult males and is frequently associated with an underlying condition, immunocompromised states, and hospitalization. Concomitant medical illnesses include chronic respiratory disease, diabetes mellitus, nutritional deficiency, malignancy, alcohol abuse, and corticosteroid therapy. In addition, similar cases are described due to aspiration in patients with elevated risk like seizure disorders.[

5] Cases of necrotizing pneumonia are reported in literature also in immunocompromised patients, including HIVpositive patients or post-transplant patients.[

6] However, in our case, there was no known medical history except for Parkinson’s disease. Regarding the pathophysiological mechanism that led to the development of necrotizing pneumonia in the present patient, the possibility of aspiration leading to bacterial colonization and pneumonia is possible, even though the patient did not have a history of swallowing disorder.

Necrotizing pneumonia commonly presents with sepsis and rapid development of acute respiratory failure. A parapneumonic effusion represents a common complication that can further be worsened with the development of massive hemoptysis, bronchopleural fistula, and bilateral diffuse pneumonia.

Streptococcus pneumoniae,

Staphylococcus aureus, and

K pneumoniae have been reported as the most common causative organisms.[

7] According to recent studies, Gram-negative pathogens, especially

P. aeruginosa and

K. pneumoniae, are associated with pulmonary gangrene and poor prognosis, as seen in our case.[

8]

Hydropneumothorax is a relatively infrequent complication of necrotizing pneumonia. It is defined as air and fluid within the pleural space and is thought to occur due to an air leak through necrotic lung parenchyma. Even though the current medical literature is limited, it is known that hydropneumothorax can occur as a complication of various other conditions such as infections, malignancy, autoimmune rheumatic diseases, esophagopleural fistula, chest trauma, or after thoracentesis.[

1] In addition, the presence of hydropneumothorax has been described recently in a spontaneously breathing patient with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia and a secondary bacterial infection.[

9] Furthermore, hydropneumothorax may be seen more frequently in patients with mechanical ventilation and positive airway pressure, which is known to increase the chances of air leaks.[

10] Although the exact underlying pathophysiological mechanism of hydropneumothorax is not precise, the presence of bronchopleural fistula from cavitary lung lesions or a leaky microvasculature after alveolar and endothelial damage induced from subsequent inflammation are two of the most accepted theories.[

4]

Hydropneumothorax and pleural effusions typically manifest with sudden onset of dyspnea and unilateral thoracic pain.[

1] The characteristic findings of parapneumonic pleural effusions are neutrophilic-predominant exudate with significantly elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels, as in the case presented herein. Furthermore, pH below 7.2, glucose below 60 mg/dL, and high lactate dehydrogenase levels, as seen in our patient, are not only indicative of complicated parapneumonic effusion but are also predictors of poor outcome.[

11] Regarding radiological findings, an important clue in chest X-ray is the presence of a new or increasing air-fluid level that can be confirmed by computed tomography.[

2] In our case, CT findings described the presence of hydropneumothorax on the same side as necrotizing pneumonia with bronchopleural fistula and featuring gangrene tissue.

Hydropneumothorax, particularly pyopneumothorax, is associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality.[

1] Its management is challenging since there are no clear guidelines specifically mentioning when to proceed from medical to surgical management.[

12] Different treatment protocols depend on the etiology, clinical presentation, and risk stratification. A combination of chest tube insertion and broadspectrum empirical antibiotic treatment may be considered as an interim option for a surgical procedure or definitive treatment in vulnerable patients.[

3] Broad-spectrum antimicrobials should be initiated immediately as per evidence-based guidelines until culture results are available, as in our patient.[

8] Surgical management involves several approaches, including video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) procedure and open window thoracotomy.[

13] According to a retrospective study, in cases of bronchopleural fistula, early surgical management featuring limited decortication and insertion of a flap is associated with reduced morbidity and shortened hospitalization compared with conservative management.[

14]

To conclude, this case highlights the need for early detection and appropriate management of hydropneumothorax. In this case, conservative management was chosen because of the patient’s and his sibling’s preferences in fear of dying perioperatively due to his frailty. It is worth mentioning that in children, conservative treatment was likewise associated with prolonged hospitalization and poor prognosis.[

15]