Abstract

Introduction: There are very few reported cases of Whipple disease (WD), a rare chronic disease in Greece. In this report, we present a classic WD case in a Greek firefighter and the detection of an autochthonous Tropheryma whipplei genotype in this Greek autochthonous citizen. Case report: We describe a patient with chronic diarrhea and arthritis who was misdiagnosed with sclerosing mesenteritis three years previously and was unsuccessfully treated with corticosteroids. After the effectuation of histopathologic examination and PCR against T. whipplei, he was diagnosed with classic WD. Moreover, for the first time in Greece, we proceeded with T. whipplei genotyping targeting four highly variable genomic sequences and we concluded that the patient was infected by T. whipplei genotype 120. Conclusions: We highlight the necessity to explore T. whipplei presence and its genotypes through the Greek population and to identify if genotype 120 is the predominant strain in the Hellenic territory.

Introduction

Classic Whipple disease (WD) is caused by Tropheryma whipplei and is considered as a rare chronic disease. [1] Classic WD manifests mainly as weight loss, arthralgia and diarrhea and is diagnosed by a histological involvement on small-bowel biopsies. In 2000, when the first T. whipplei cultures were done, WD was thought to be caused from an uncommon bacterium but to date it is established that T. whipplei can determine chronic, localized infections without systemic involvement, as well as asymptomatic carriage. [2] Acute infections such as gastroenteritis, pneumonia and bacteremia have been also associated with T. whipplei infection. [2] Asymptomatic stool carriage of the bacterium has been also diagnosed with different prevalences depending on geographic area, age and exposure. [3] In France, the prevalence of T. whipplei seems to be higher among sewage workers (12-26%) and homeless people (13%) rather than in the general population (4%). [4] It is believed that humans are infected by the oro-oral route in good living conditions and by the fecal-oral route in poor living hygiene conditions. Contact with feces or saliva was also found to be a possible route for the transmission of the bacteria, as T. whipplei can be grown from both fecal and saliva samples. [3] Until nowadays, there are very few reported cases of WD and studies regarding T. whipplei infection in Greece. Indeed, we have recently reported a high presence of T. whipplei in migrant children living in Greece. [5] In this article, we present a classic WD case in a Greek firefighter and the detection of a T. whipplei genotype in a Greek autochthonous citizen.

Case report

A 68-year-old male, retired firefighter, presented to the Emergency Department with a three-year history of fatigue, diarrhea, early satiety, weight loss of about 25 kg and migratory arthritis of the elbows, wrists and knees. Written consent was obtained from the patient. He did not report any recent travelling abroad. He had been diagnosed with sclerosing mesenteritis and he was on therapy with methylprednisolone for the past 2 years. Past medical history also included moderate pulmonary hypertension (RSVP 55-60 mmHg), heterozygous beta thalassemia, and past successful Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy.

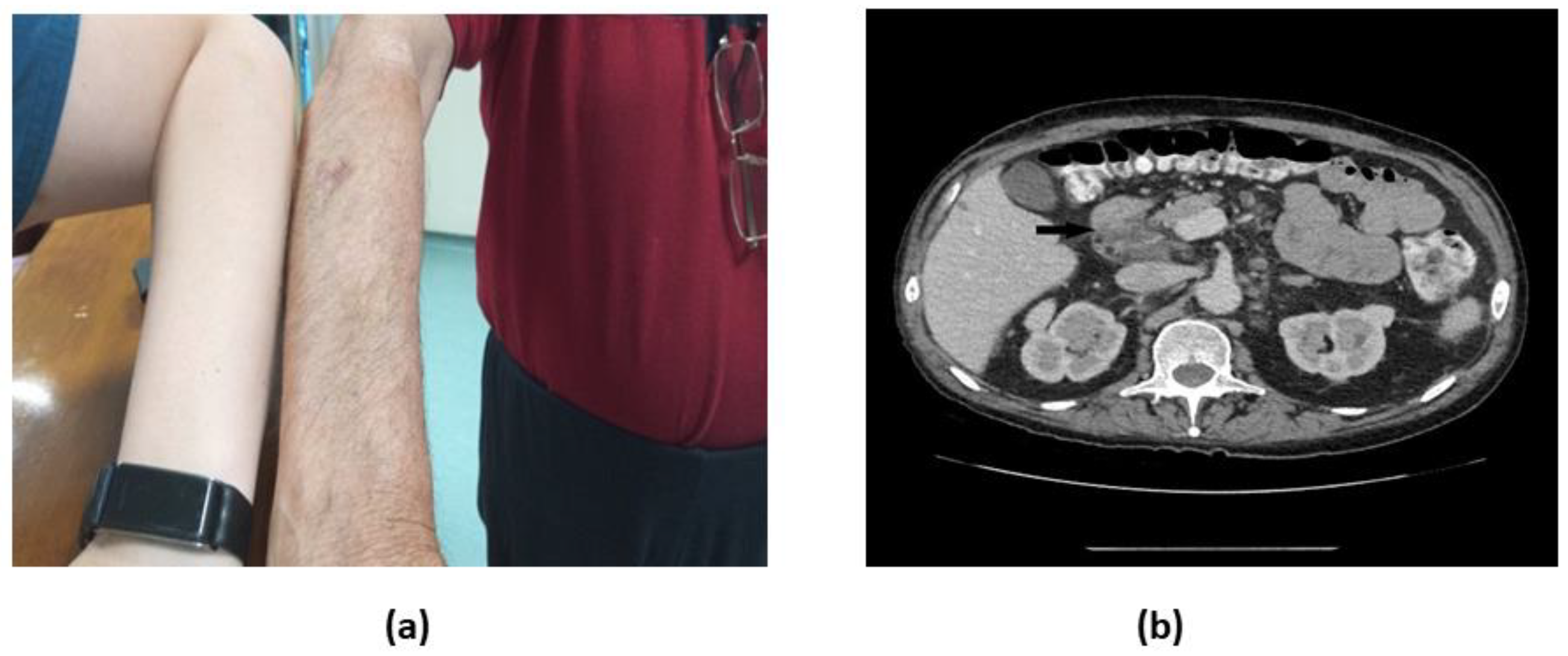

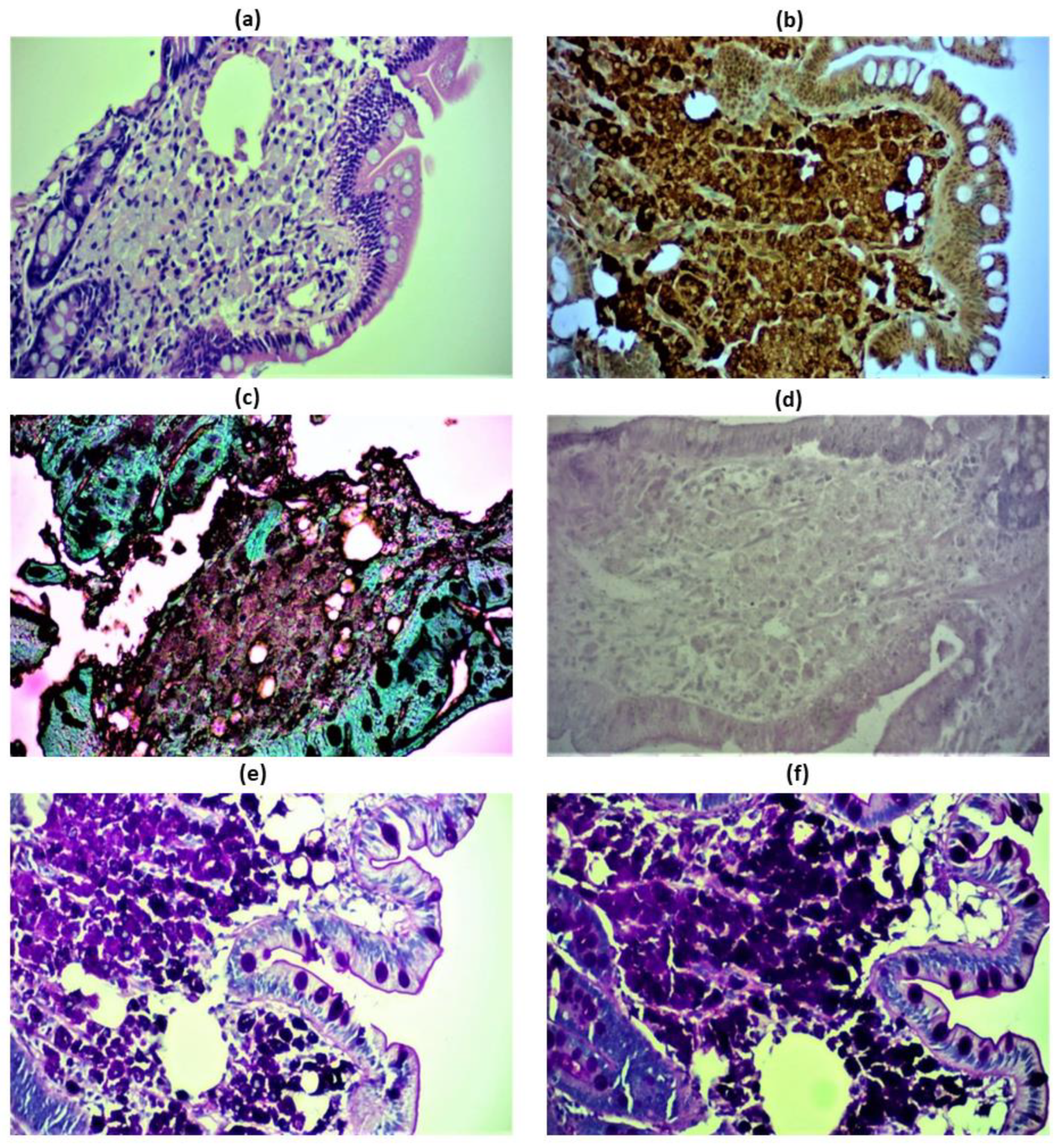

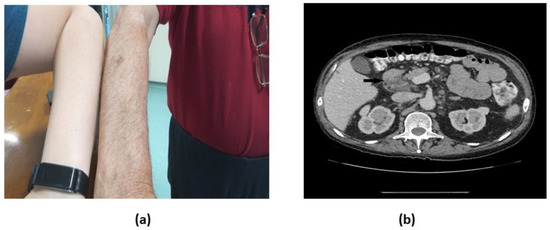

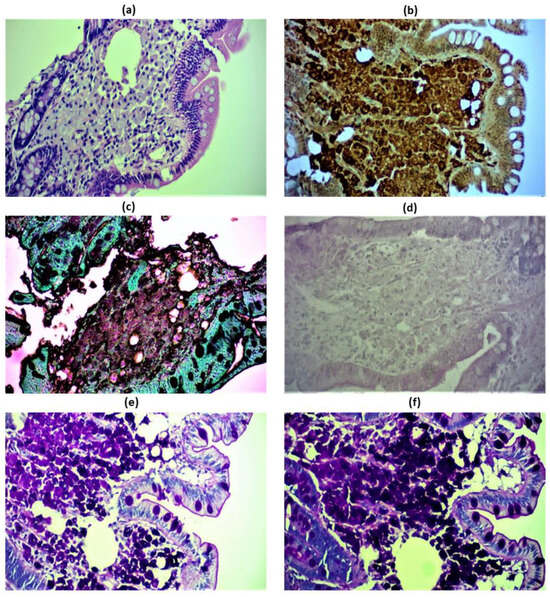

Physical examination showed an ill-appearing patient with a remarkably dark skin, jugular venous distention and a hepatojugular reflux (Figure 1a). Neurologic examination was insignificant. Laboratory examination revealed a hypochromic microcytic anemia (Hb 9.7 g/dL, Ht 31.5%), severe B12, folic acid and ferritin deficiency, and a mildly elevated C reactive protein (CRP 52 mg/dL, normal range <10 mg/L). Serum protein electrophoresis showed polyclonal IgG elevation. Despite the absence of neurologic manifestations, the possibility of occult CNS infection prompted us to perform a lumbar puncture in order to exclude CNS dissemination of the bacterium and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination was normal. CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis showed mesenteric lymphadenopathy (Figure 1b) and associated mesenteric fat edema (“misty mesentery” sign). The patient underwent upper and lower GI endoscopy that revealed mild mucosal inflammation and biopsy samples were obtained from the stomach, duodenum, ileum and colon. Microscopical findings were mostly limited to the duodenum, while biopsies obtained from the colonic and the gastric mucosa were normal. A mesenteric lymph node CT-guided biopsy was performed, as well. Histopathologic examination of the duodenal sample revealed PAS-stain and CD68 positive foamy macrophages (Figure 2a,b), partially positive Grocott staining (Figure 2c) and Ziehl-Neelsen-negative staining (Figure 2d). PAS and PAS-diastase positive staining, characteristic of the glycoprotein cell walls of both viable and nonviable organisms (Figure 2e,f).

Figure 1.

a. Physical and b. Axial abdomen CT scan with i.v. contrast demonstrating paraaortic and mesenteric lymphadenopathy, including an enlarged lymph node measuring 45×27 mm in the hepatoduodenal ligament with partial fatty replacement (black arrow).

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical images of the patient’s duodenal and lymph node biopsies revealing classic Whipple’s disease. Hematoxylin/eosin staining of foamy macrophages in the lamina propria, beneath the epithelium (a). Positive CD68 staining of foamy macrophages of the duodenal lamina propria (b). Duodenal macrophages tested negative for Grocott methenamine silver (GMS) stain, that is used to detect histoplasmosis (c). Negative Ziehl-Nielsen staining used to exclude Mycobacterium avium intracellulare complex, a PAS—stain positive acid fast group of bacilli. Mycobacterium avium intracellulare complex has a similar microscopic morphology to Tropheryma whipplei on an H&E stain and is also PAS positive. Acid fast bacilli would be stained bright red (d). Positive Periodic acid Schiff (e) and PAS-diastase—positive staining (f) of the duodenal epithelium stained magenta, which stain the glucoprotein of both viable and non-viable microorganisms. Magnification 100x.

DNA was extracted from one stool specimen and two formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded biopsies originated from the duodenal and the lymph nodes, respectively, using a QIAamp DNA MiniKit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. We used qPCR for the β-actin housekeeping gene to check the quality of DNA handling and blood specimen extraction. [4] Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) assays, using specific oligonucleotide TaqMan probes targeting a 155 bp and a 150 bp T. whipplei repeated sequence, were performed, as previously described. [4,6] All three samples presented the two specific genes positive at a log-based fluorescence cycle threshold (Ct) of <35, leading to classic WD diagnosis. PCR analysis was negative in blood samples; moreover, a lumbar puncture was performed in order to exclude central nervous system involvement by CSF PCR analysis for T. whipplei, that resulted negative, as well. The patient was immediately started on intravenous ceftriaxone (2 g qd) for 2 weeks, and was discharged on doxycycline (100 mg bid) and hydroxychloroquine (200 mg tid) for 12 months. He is currently on his seventh month of treatment and on his last follow-up appointment, he reported complete resolution of symptoms, a gradual weight gain of 6 kg, and a significant improvement in his appetite and his quality of life. As per laboratory parameters, a notable improvement in the patient’s anemia (Hb 13.8 mg/dL, Ht 42.3%) was observed, as well as gradual resolution of hyperglobulinemia and nutrient deficiency.

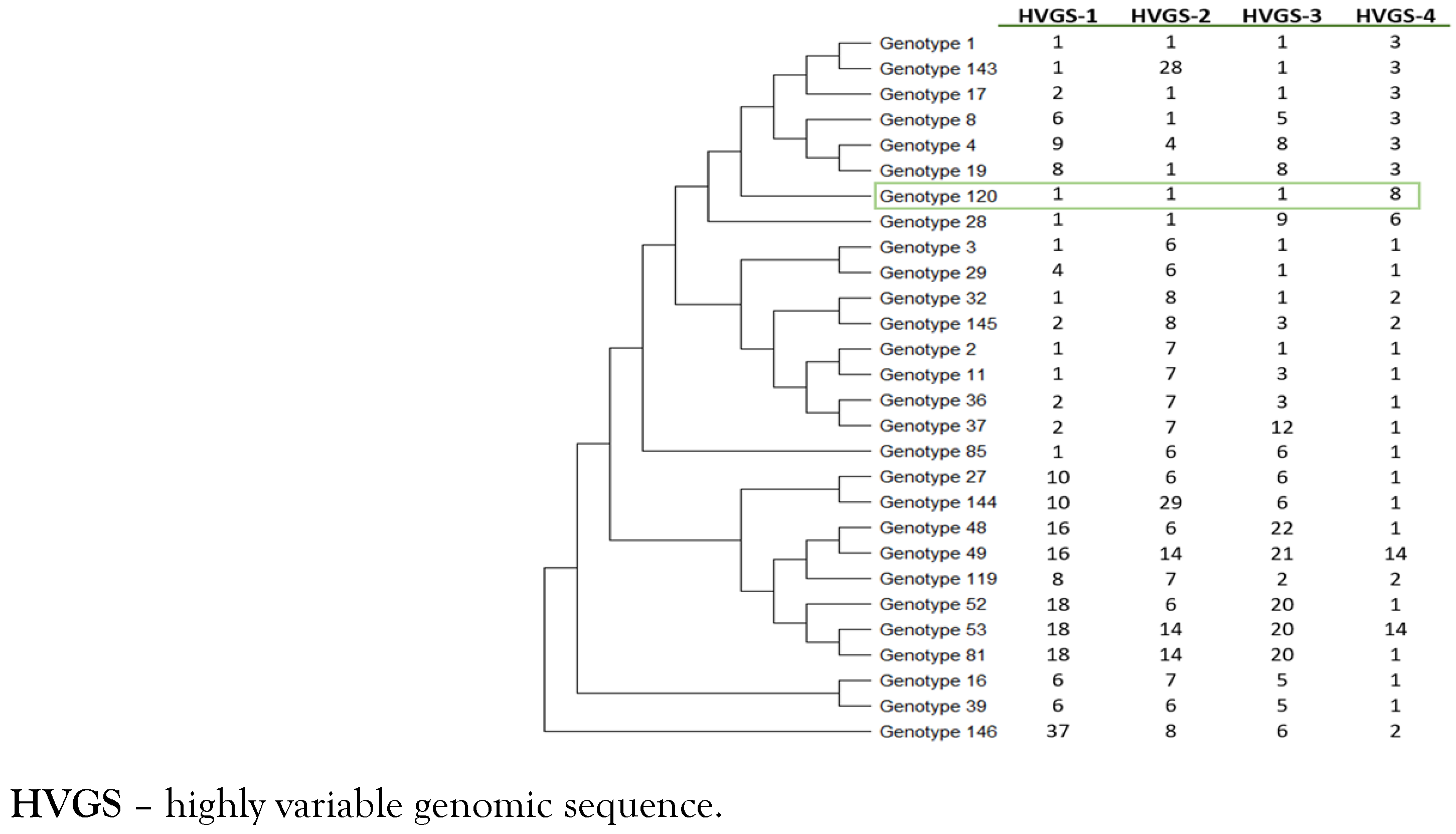

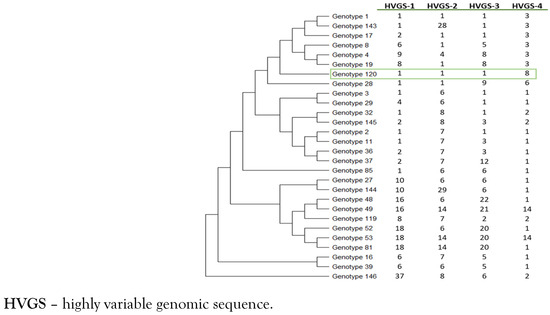

Finally, genotyping was performed using a multispacer system, targeting four highly variable genomic sequences (HVGSs) as previously described. [7,8] The four HVGSs obtained were compared with those available in both the GenBank database and those listed on the Institut Hospitalo—Universitaire Méditerranée Infection website (Multispacer Typing—T. whipplei, https://ifr48.timone.univ-mrs.fr/mst/tropheryma_whipplei) to determine their corresponding genotype. We identified that this patient was infected by T. whipplei genotype 120 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic diversity of genotype 120 of Tropheryma whipplei obtained from the patient (green box). The phylogenetic tree was constructed by using the maximum-likelihood method based on the Tamura 3-parameter substitution model. Sequences from the 4 HVGSs were concatenated.

Discussion

We report a case of classic WD with sclerosing mesenteritis and the detection of T. whipplei genotype 120 in Greece. The diagnosis was established by molecular assays and, to our knowledge, this is the first report that determines a T. whipplei genotype in a Greek autochthonous citizen. The genotyping of the bacteria showed high genetic diversity unrelated to pathogenicity. [9] T. whipplei genotype three is considered as the most frequent genotype in Europe, appearing to be epidemic and specific in many countries including France, Switzerland, and Italy. [7] T. whipplei genotype 1, the second most frequent genotype in central Europe, has been considered predominant in Germany and Austria. [2,3] Genotype 85 was reported from a case cluster in homeless people from the same shelter. Circulation among family members has also been reported, with the same genotype being most often detected in relatives. [5] So far, no specific association has been reported between T. whipplei genotype and disease state versus asymptomatic carriage, and the same genotype can be found in acute and chronic infections and/or asymptomatic carriage. To the best of our knowledge, there are no published reports about T. whipplei genotype 120. In addition, we recently found a high presence of T. whipplei in children living in migrant hot spots in Greece but we did not identify T. whipplei genotype 120 among the six different T. whipplei genotypes circulating in these children. [5] As a result, no association between T. whipplei genotype 120 and the patient’s symptoms can be done because of the absence of data regarding this T. whipplei. The patient was a retired firefighter, which possibly explains the infection with T. whipplei. Indeed, the detection of T. whipplei in sewage treatment plants suggests a possible environmental source of the bacterium. [3] People who live under poor hygiene conditions, and particularly children, display increased rates of infection with T. whipplei compared with the general adult population. [5]

The patient will be treated by doxycycline and hydroxychloroquine for one year and a lifetime doxycycline treatment will follow. This treatment was chosen because patients with WD can present several relapses with the same genotype despite treatment and also it was found that they can develop a new episode with another T. whipplei strain. [10] We did not use a treatment with intravenous ceftriaxone followed by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole as trimethoprim is found to be inefficient for the bacteria and this resistance has been associated with failures and relapses of the disease. [2,3]

Conclusions

We report the detection of a T. whipplei genotype in a Greek autochthonous citizen suffering by classic WD. Our findings underline the necessity to explore T. whipplei presence and its genotypes throughout the Greek population and, among all, to identify if genotype 120 is the predominant strain in the Hellenic territory.

Author Contributions

A.K.: Clinical examinations, follow-up and manuscript writing; S.M.: PCR, genotyping and manuscript writing; T.S.: Manuscript writing and editing; M.K.: PCR and genotyping; P.K., M.P., N.C., C.T. and E.M.: Clinical examinations and follow up; E.A.: Supervising the study, manuscript writing and editing; P.P.: Supervising the clinical cases. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

None to declare.

Conflicts of interest

All authors—none to declare.

Consent

Written consent was obtained for the patient for the publication of this case and the accompanying images.

References

- Marth, T.; Moos, V.; Müller, C.; Biagi, F.; Schneider, T. Tropheryma whipplei infection and Whipple’s disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016, 16, e13–e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagier, J.C.; Fenollar, F.; Raoult, D. Acute infections caused by Tropheryma whipplei. Future Microbiol. 2017, 12, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keita, A.K.; Raoult, D.; Fenollar, F. Tropheryma whipplei as a commensal bacterium. Future Microbiol. 2013, 8, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenollar, F.; Marth, T.; Lagier, J.C.; Angelakis, E.; Raoult, D. Sewage workers with low antibody responses may be colonized successively by several Tropheryma whipplei strains. Int J Infect Dis. 2015, 35, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makka, S.; Papadogiannaki, I.; Voulgari-Kokota, A.; Georgakopoulou, T.; Koutantou, M.; Angelakis, E. Tropheryma whipplei intestinal colonization in migrant children, Greece. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022, 28, 1926–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelakis, E.; Fenollar, F.; Lepidi, H.; Birg, M.L.; Raoult, D. Tropheryma whipplei in the skin of patients with classic Whipple’s disease. J Infect. 2010, 61, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Fenollar, F.; Rolain, J.M.; et al. Genotyping reveals a wide heterogeneity of Tropheryma whipplei. Microbiology (Reading) 2008, 154 Pt 2, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenollar, F.; Trape, J.F.; Bassene, H.; Sokhna, C.; Raoult, D. Tropheryma whipplei in fecal samples from children, Senegal. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009, 15, 922–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keita, A.K.; Bassene, H.; Tall, A.; et al. Tropheryma whipplei: A common bacterium in rural Senegal. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011, 5, e1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagier, J.C.; Fenollar, F.; Lepidi, H.; Raoult, D. Evidence of lifetime susceptibility to Tropheryma whipplei in patients with Whipple’s disease. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011, 66, 1188–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© GERMS 2023.