Introduction

Immunization has remained the most cost-effective public health intervention, which has significantly reduced morbidity and mortality of children from vaccine-preventable infectious diseases [

1]. Therefore, all health systems must ensure high levels of coverage are attained [

2]. In Nigeria, the provision of immunization is primarily within the purview of the primary healthcare centers (local level) however, the other two tiers of government (federal and state) and the private sector play a great role as well. The Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI), which was initiated in 1978 in Nigeria, was the major avenue through which routine immunization was provided to under-five children. It protected against the six killer diseases (tuberculosis, pertussis, diphtheria, tetanus, poliomyelitis and measles), which commonly affect this group of children [

2]. However, in 1995, the EPI was renamed the National Programme on Immunization (NPI) and in 1996 it was formally launched [

3]. Since then, several vaccines have been added to the schedule including the hepatitis B vaccine [

4],

Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine (HiBCV) and pneumococcal vaccine (PCV). The NPI schedule proposed that children aged 12–23 months should be fully immunized with all these vaccines [

2].

In 2017, about 19.9 million infants worldwide couldn’t be reached with routine immunization services, out of which 60% were living in low- and middle-income countries such as Afghanistan, Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Iraq, South Africa, Pakistan and Nigeria [

2]. Studies in India [

5], Indonesia [

6] and Nigeria [

7] revealed low immunization in under-five children with coverage of between 23% and 65.4%. In Nigeria, in the early 1990s, the childhood immunization coverage reached 81.5% but it progressively declined to about 30% in 1996 and as low as 12.9% in 2003 [

2]. Furthermore, the 2016/2017 Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey/National Immunization Coverage Survey (MICS/NICS) report showed variations of the immunization coverage in different parts of Nigeria; with the North West having the weakest performance of 8% complete immunization coverage, the South East, 44%, South-South 43%, South West 50% while the North East 20% and North Central 26% and these are below the global goal of ≥80% [

8,

9].

A previous study conducted in Jos, Plateau state 21 years ago showed that the overall immunization rate with the EPI vaccines was 62.4% as opposed to the acceptable national vaccine coverage of ≥80%. Factors like male sex, lack of maternal education, home delivery, ethnicity, religion, place of domicile and low socio-economic status were associated with inadequate immunization [

4]. In more recent years, new vaccines have been introduced into the EPI schedule of immunization, which could also come with its challenges. This study, therefore, aimed to determine the current immunization status of children 1–5 years of age seen at the Emergency Pediatric Unit (EPU) post-introduction of the new vaccines, to identify factors affecting immunization in these children and to recommend ways of improving immunization uptake.

Discussion

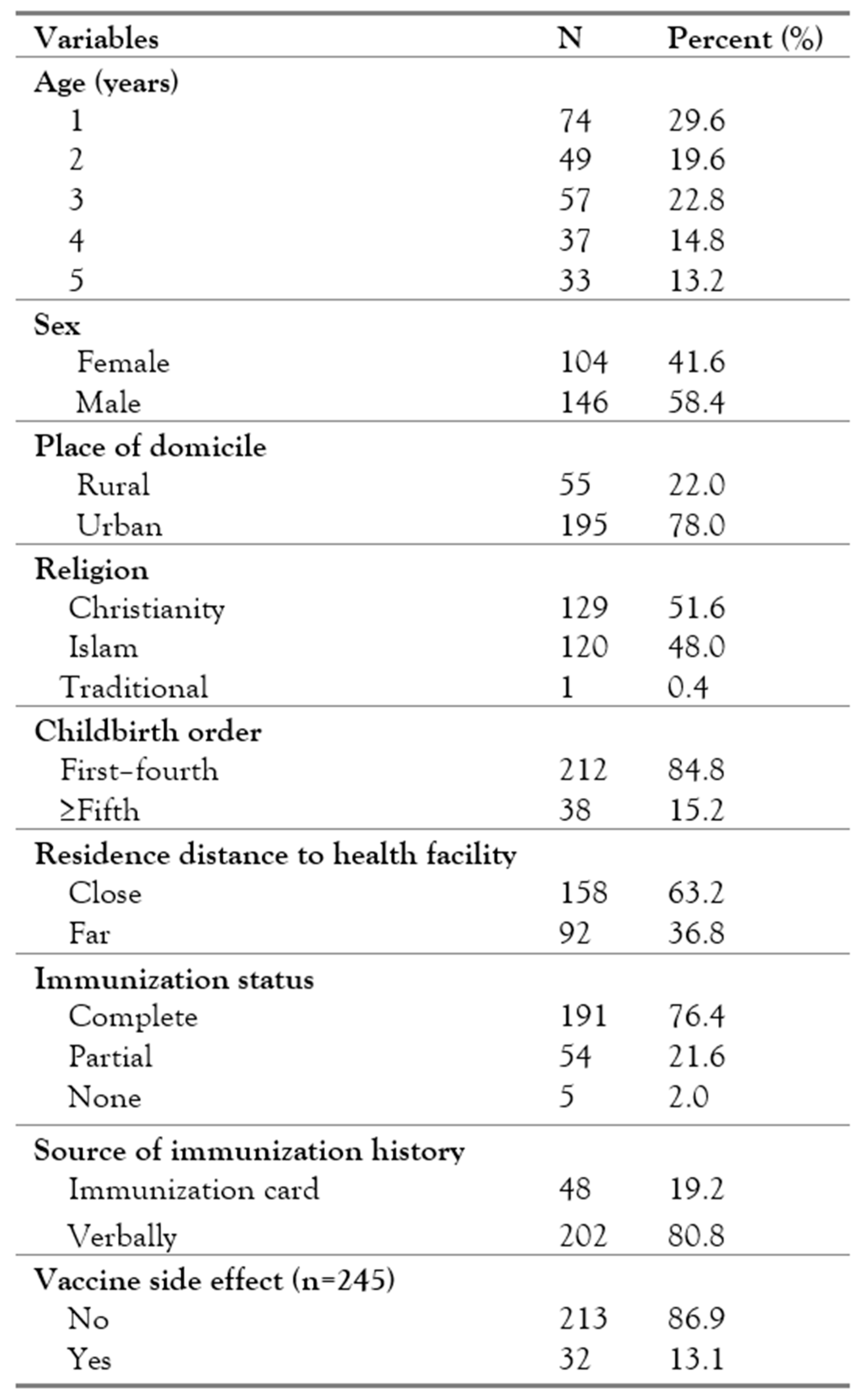

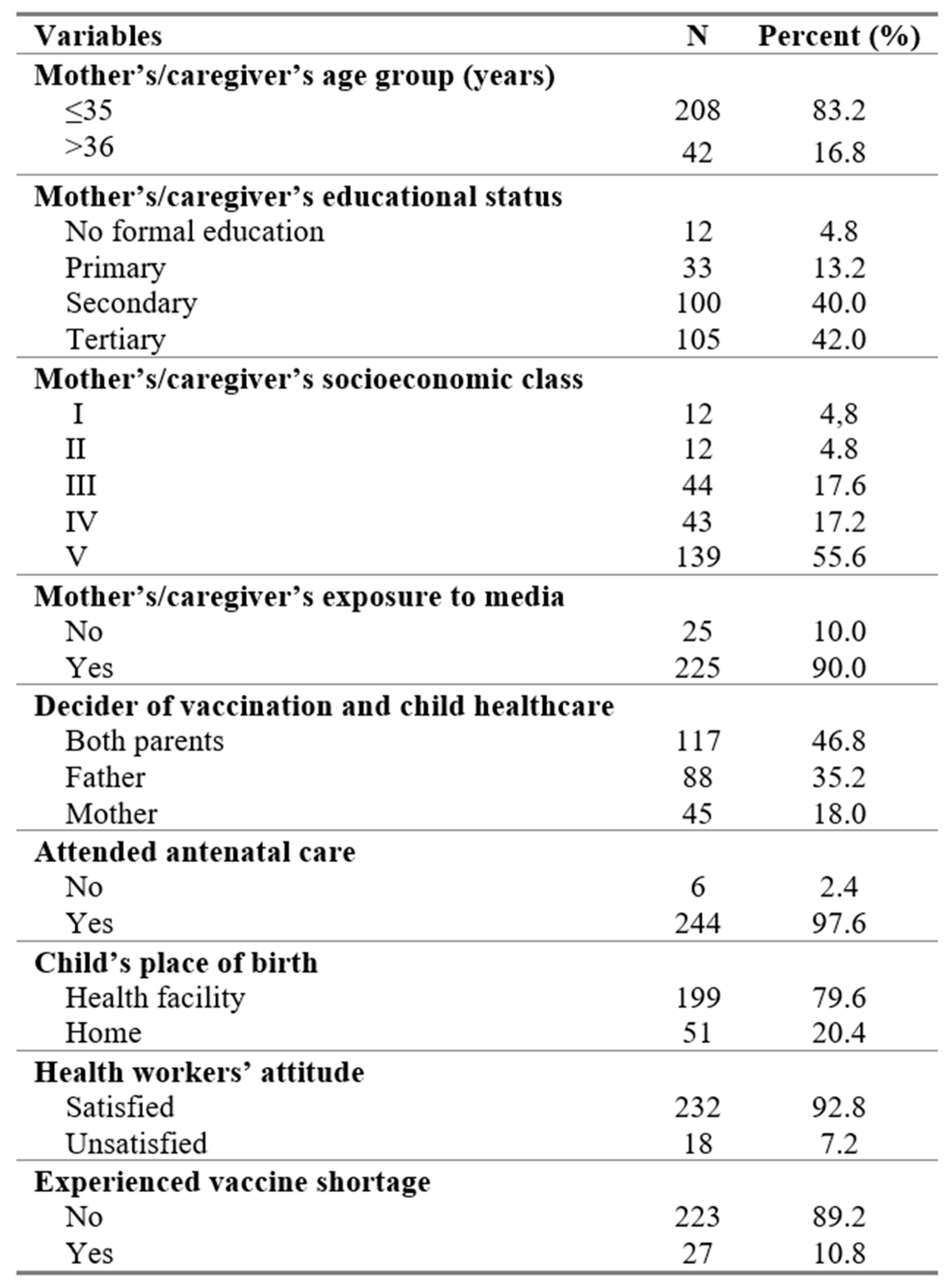

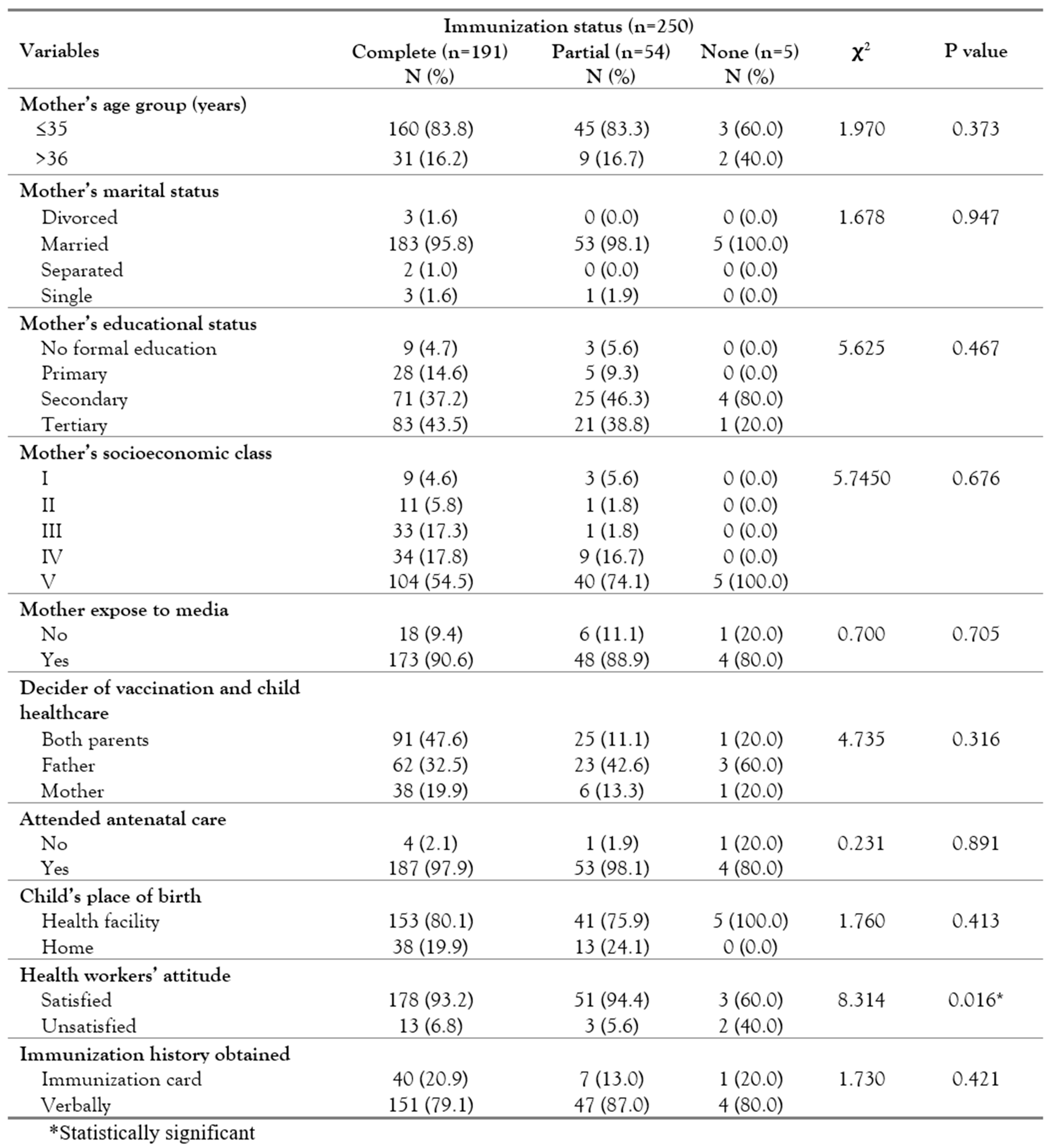

This study found that 76.4% of the children were fully immunized with more males than females being immunized. The association between sex and immunization status was however, not statistically significant. A similar study conducted 21 years ago in the same institution with the EPI vaccines reported that 62.4% of the children were fully immunized for age [

4]. The current study has shown some improvement, however, the rates in both studies are still below the acceptable national vaccine coverage of ≥80% [

11]. The improvement in the immunization rate in the current study is probably due to the fact that majority of the mothers/caregivers in this study were more formally educated compared to the previous study. In addition to this, the introduction of the new vaccines (HiBCV and PCV) could have contributed to increasing the zeal of the caregivers to take their children for immunization.

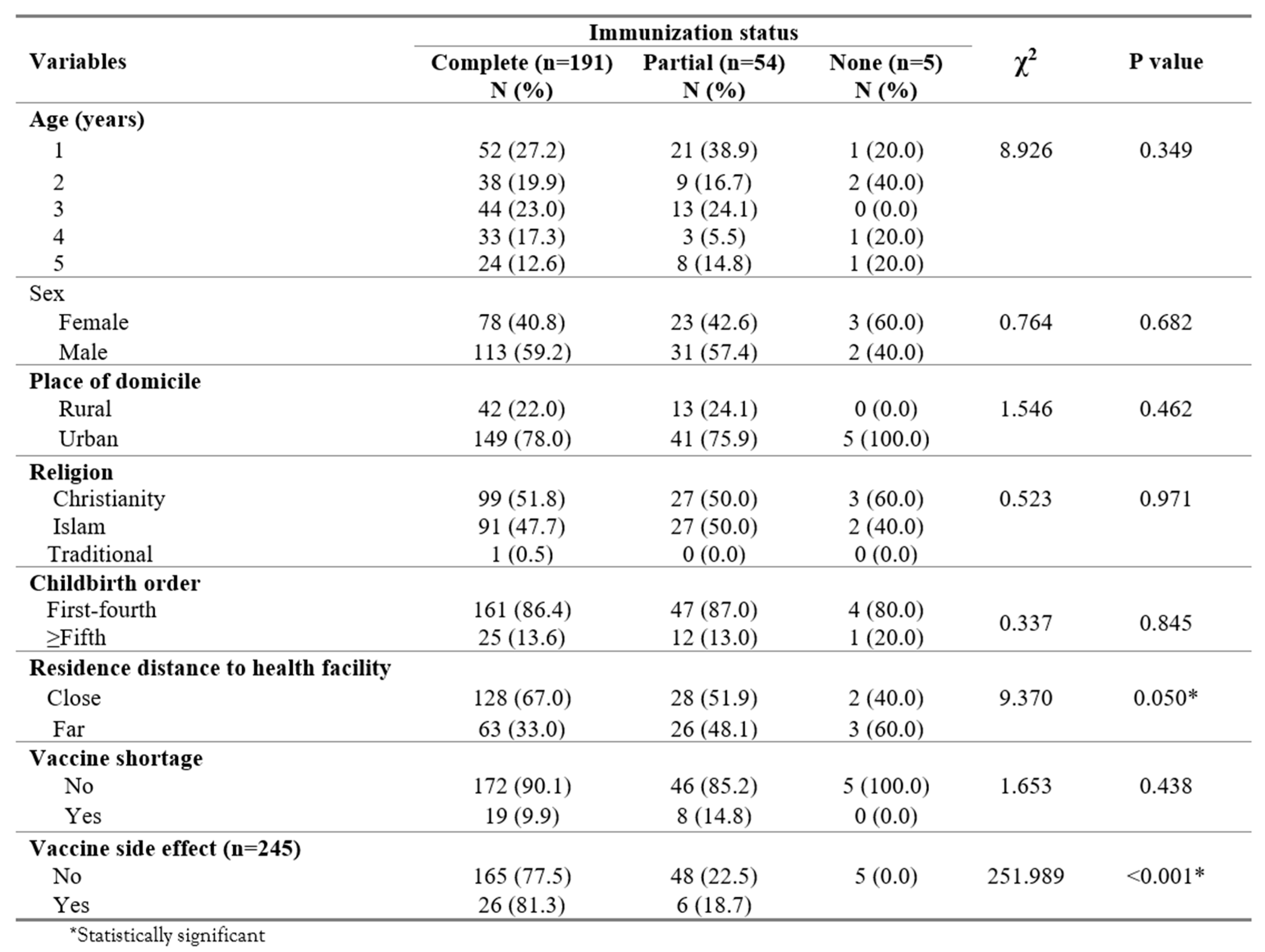

The child’s age and birth order in this study did not influence the immunization status of the children and this was similar to the report from Keffi, Nigeria [

12] and at variance with the observation by Herliana and Douiri in Indonesia in 2017 [

6] which demonstrated that higher birth order and older children have a lower chance of being fully immunized. The mother’s age had no influence on the completion of immunization in this study, which was similar to the findings in some other studies [

6,

13]. However, this finding was at variance with the findings from a National Demographic and Health Survey in Nigeria in 2013 [

14] and a report from Lagos, Nigeria [

15] where the older the mother was, the more likely the child was to get immunized. The lack of difference of the child’s birth order and mother’s age with immunization status of the child could be because the majority of the mothers/caregivers were educated, which could have improved the children’s immunization uptake.

This study did not find a significant association between the child’s birthplace and immunization status but this was at variance with other reports from Nigeria [

7,

12]. Most of the patients in this study probably had complete immunization because they were delivered in a health facility. In addition, the women exposed to the media in this study completely immunized their children however, this finding was not statistically significant. It is known that the media plays a key role in influencing the uptake of immunization and this has been reported by researchers in some previous studies who observed that exposure to the media had a positive influence on complete immunization status [

6,

14].

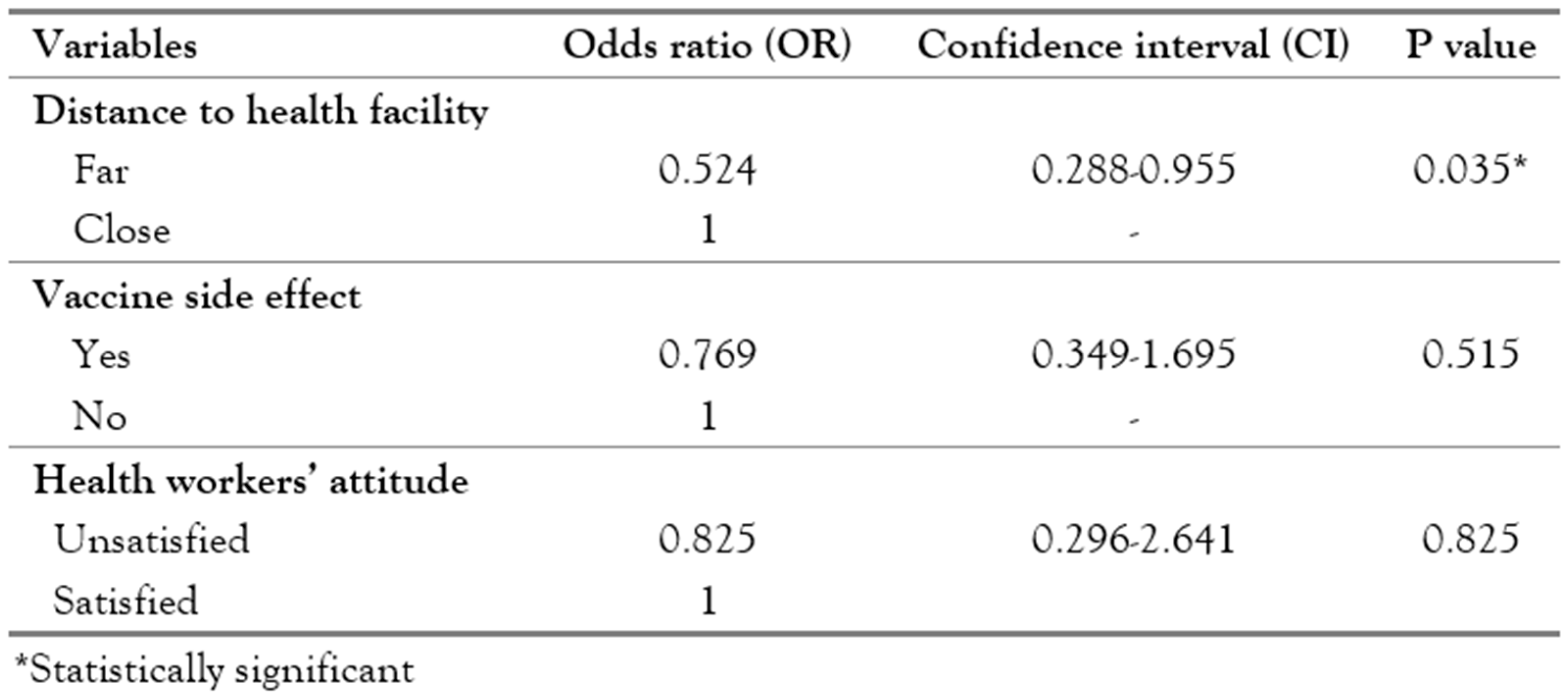

Living far away from a health facility has a negative influence on the complete immunization status of the children with those living far from a health facility being less likely to get vaccinated compared to those that live close to the health facility (if the caregiver has to walk for <30 min or does not require any means of transportation before getting to the immunization center). This finding agrees with that of other studies that demonstrated that distance from the health facility can be a problem to accessing immunization [

12,

16]. The implication of considering distance alone without considering the availability of transport and the terrain may hinder parents from taking their children for immunization.

Children that had vaccine side effects in this study were less likely to complete their immunization which is similar to the finding of previous studies [

12,

17]. Side effects of vaccination are usually rare and most of the time mild. It is known that some children may experience these side effects and this is usually manageable with the education of mothers/caregivers especially during antenatal care. If healthcare providers do not provide adequate information on how to address these problems as the benefit of the immunization far outweighs those side effects, it can deter women from coming for immunization. In addition, mothers being unsatisfied with healthcare workers’ attitude had a negative effect on the completion of immunization in this study, a finding that was not statistically significant. A poor attitude will negate all the gains made in trying to ensure that children are completely immunized even if all vaccines are made available at all immunization centers.

The place of domicile did not significantly affect complete immunization in this study. However, this finding was at variance with what was observed in a study by Adenike [

12] who found that those who lived in urban areas were more likely to fully immunize their children compared to their rural counterparts. This could be as a result of the efforts by the government of Nigeria to distribute vaccines to the primary, secondary and tertiary health facilities including private health facilities to help improve access to the vaccines. In addition to this, the government has also provided solar-powered vaccine refrigerators to maintain the vaccine cold chain in different rural and urban areas to ensure the potency of the vaccines. This might explain why the majority of the respondents confirmed that there was no vaccine shortage.

The place of delivery and antenatal care visits had no effect on the status of immunization in this study but most of the children were delivered in a health facility and their mothers had antenatal care (ANC) and most of them were completely immunized. A previous study established that delivery by a skilled birth attendant and attendance of antenatal care visits were important factors associated with complete vaccination [

7]. The variation in the research findings could be a result of variations in the sample size in which the latter has a very large sample size. Health facilities are still important places where important information regarding childhood immunization are given to mothers during antenatal and postnatal care. However, some mothers could have missed this if they came late or were distracted during the health talks. In addition to this, some mothers never attend postnatal care visits when required [

18].

Marital status in this study was not related to immunization status, a finding that was similar to that of a study in Lagos, Nigeria [

14]. However, this finding is in contrast to the findings by Anokye [

13] and Adedokun [

14] who found a significant relationship between marital status and incomplete immunization. The variation found between this study and other studies could be attributable to the fact that the categorization of marital status used in this study is different from the other studies and that could have resulted in the differences observed. Also, unlike other studies [

19,

20] that established a strong association between religion and immunization, this study could not establish a significant association between religion and complete immunization. Previously, in Nigeria, there have been issues concerning the immunization of children in some parts of the country. Recently, efforts are being made to raise awareness on the importance of immunization through the media, religious and traditional leaders. This could have been responsible for increased immunization and the lack of difference in immunization uptake between the two dominant religions in the country.

Parent’s education was not significantly related to the immunization status of the children in our study. On the contrary, a study from Indonesia revealed that maternal education was a major determinant of immunization coverage [

6]. The differences could be because the studies were conducted using different methodologies. Education provides an avenue for individuals to obtain information on the importance of immunization, schedule of immunization, places to go for immunization and also how to address adverse reaction to immunization, thereby developing increased confidence in immunization uptake.

Parent’s occupation has been shown to influence the immunization of children but in our study, we found no statistically significant association between immunization uptake and parents/caregiver’s occupation. Some researchers [

14,

15] have demonstrated that the mother’s occupation had a significant relationship with the immunization status of the child. A study from Indonesia [

6] also reported that both parents’ occupations (depending on the type) have a statistically significant relationship with the immunization status of the children. In our study, parents who jointly decide on maternal healthcare were less likely to have unimmunized children, but this was not statistically significant. This shows the importance of family support with using health services, as postulated by Andersen [

21]. It is essential to combine the mother’s autonomy with the father’s involvement in the decision-making process, suggesting that interventions aimed at also educating and involving the fathers could increase immunization coverage [

22].

The sex of a child was not a significant predictor of full immunization in our study, a finding that is similar to those from studies by Antai [

20] and Adebiyi [

23] from Nigeria and Herliana and Douiri [

6] from Indonesia. This is in contrast with a study from India where the sex of a child had a significant impact on immunization [

24]. Gender could predict immunization status only if the child is from a society where gender inequality is prevalent [

24]. Over time, the girl child has gradually been accepted as equal to the male child in our society and therefore the gender inequality which is gradually phasing out could have resulted in this lack of sex difference in this study.

The source of information on the immunization status of the children in this study shows that the majority of it was obtained verbally and this may not be accurate as this would depend on the ability to recall past information. A study in the UK by Nohavicka et al. [

25] found out that when using history, the rate of incomplete immunization was 5.5% compared to 6.9% that was found using their primary care trust (PCT) data.

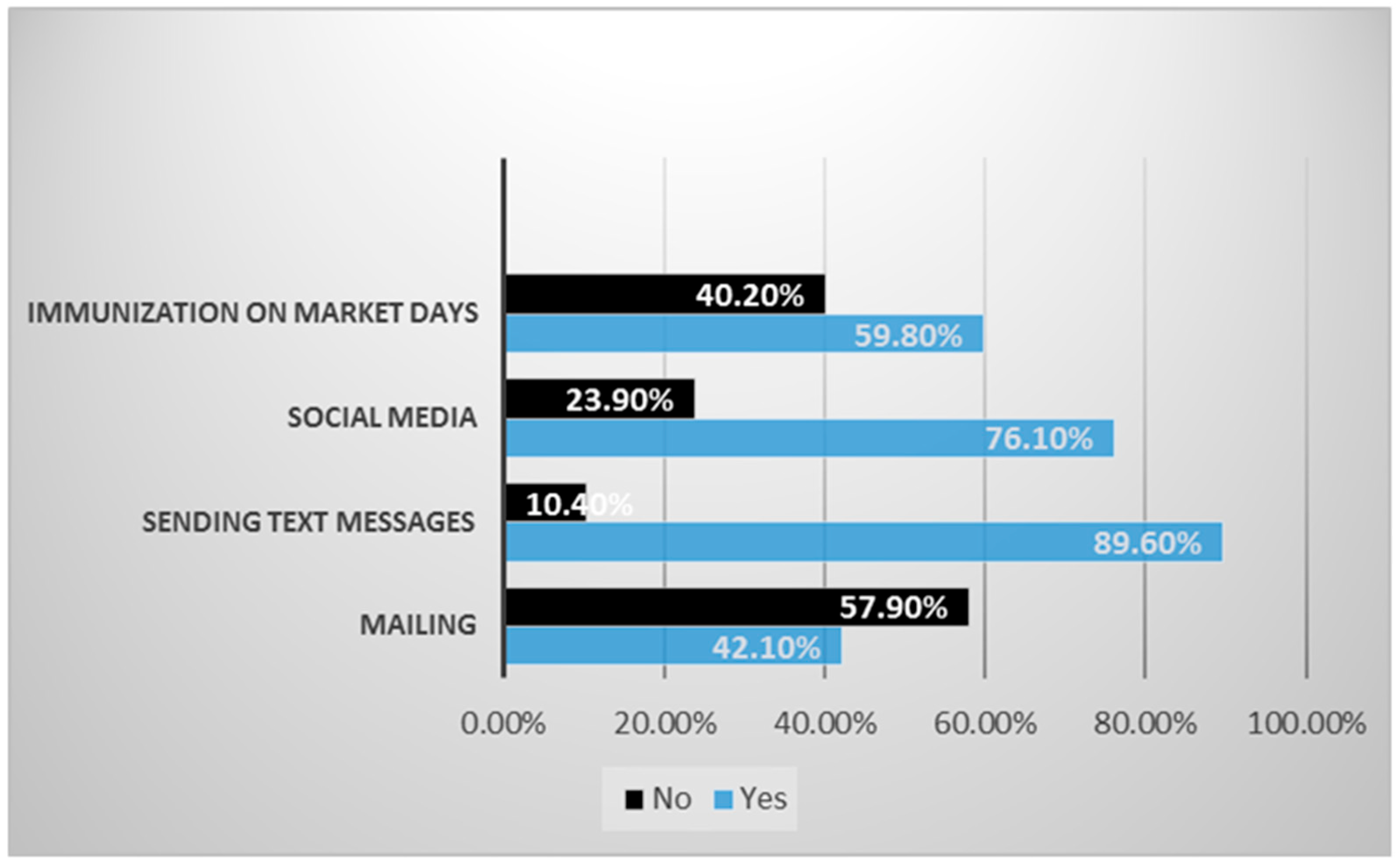

Several factors influencing immunization uptake have been highlighted earlier but it is important to involve all relevant stakeholders including mothers/caregivers in the delivery of immunization. Therefore, mothers’/caregivers’ perception of ways to improve immunization uptake was assessed in this study. Most of the mothers suggested the use of a short message service (SMS) to send reminders to them. Others suggested the use of social media like Facebook, WhatsApp as well as using market days for immunization to increase the uptake of immunization. Short messaging services (SMS) will surely increase the speed of communication and immunization uptake as most people including mothers have mobile phones. Therefore, partnering with telecommunication operators will be able to achieve this. The use of market days for immunizations as suggested by some responders should incorporate health education and advocacy involving community leaders. These are not exhaustive because other ways like the use of peer educators to improve immunization uptake was demonstrated by Banwat et al. [

16], in Jos, Nigeria and Kumar & Kumar [

5] in North India who also developed an e-governance conceptual framework in India to improve the immunization processes in India using ICT.

The design of this study being cross-sectional is limited in establishing temporal relationship between the independent and outcome variables although odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals have been used as the point and interval estimates of the effects of the independent variables on the immunization status. Furthermore, the immunization status of the children was self-reported by the caregivers/mothers, making self-desirability responses possible and the possibility of recall bias. Finally, this study being a single hospital-based study may limit the generalizability of its findings.