Fatal Septic Shock Caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus Diagnosed by 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

Abstract

Introduction

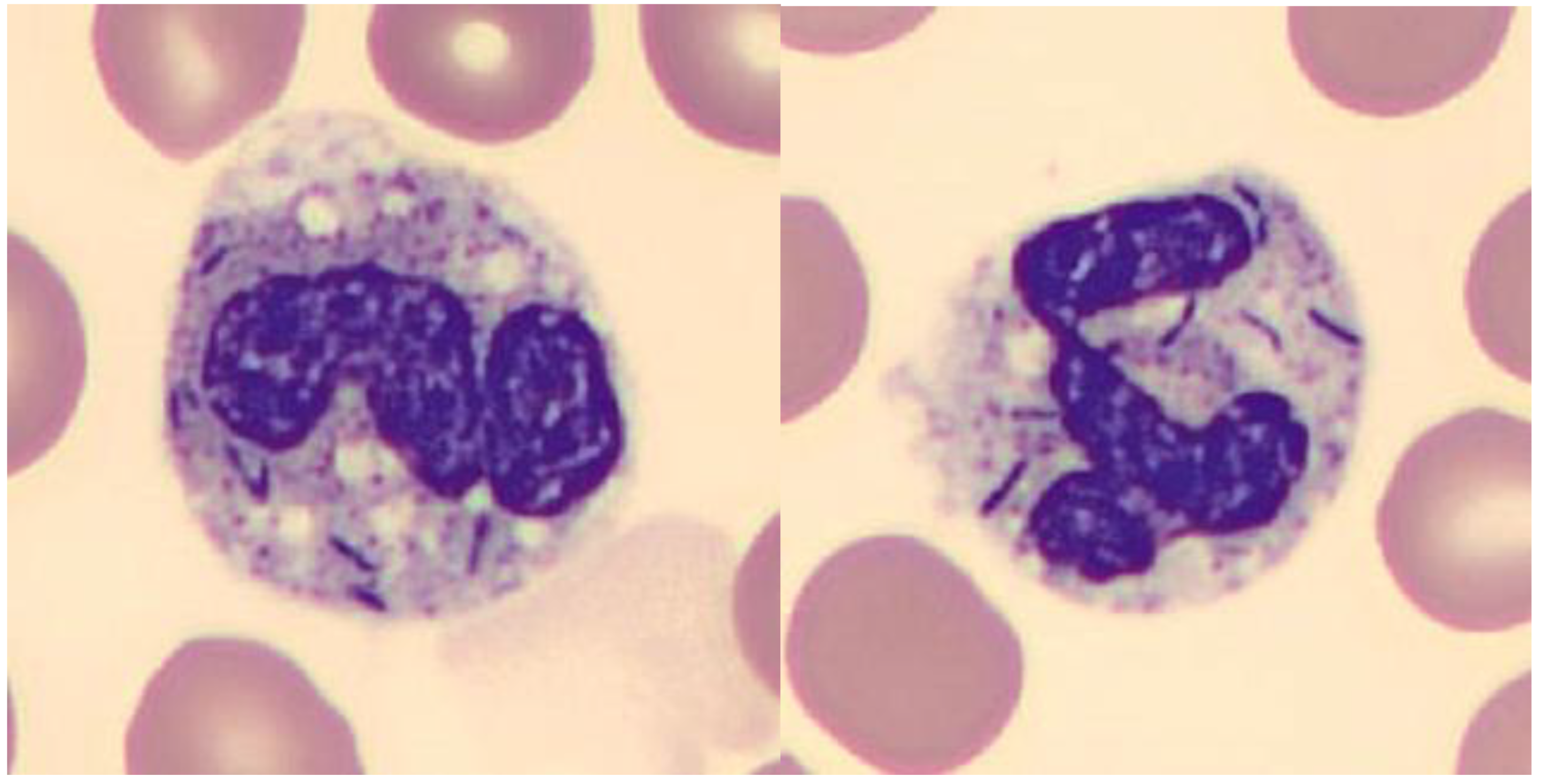

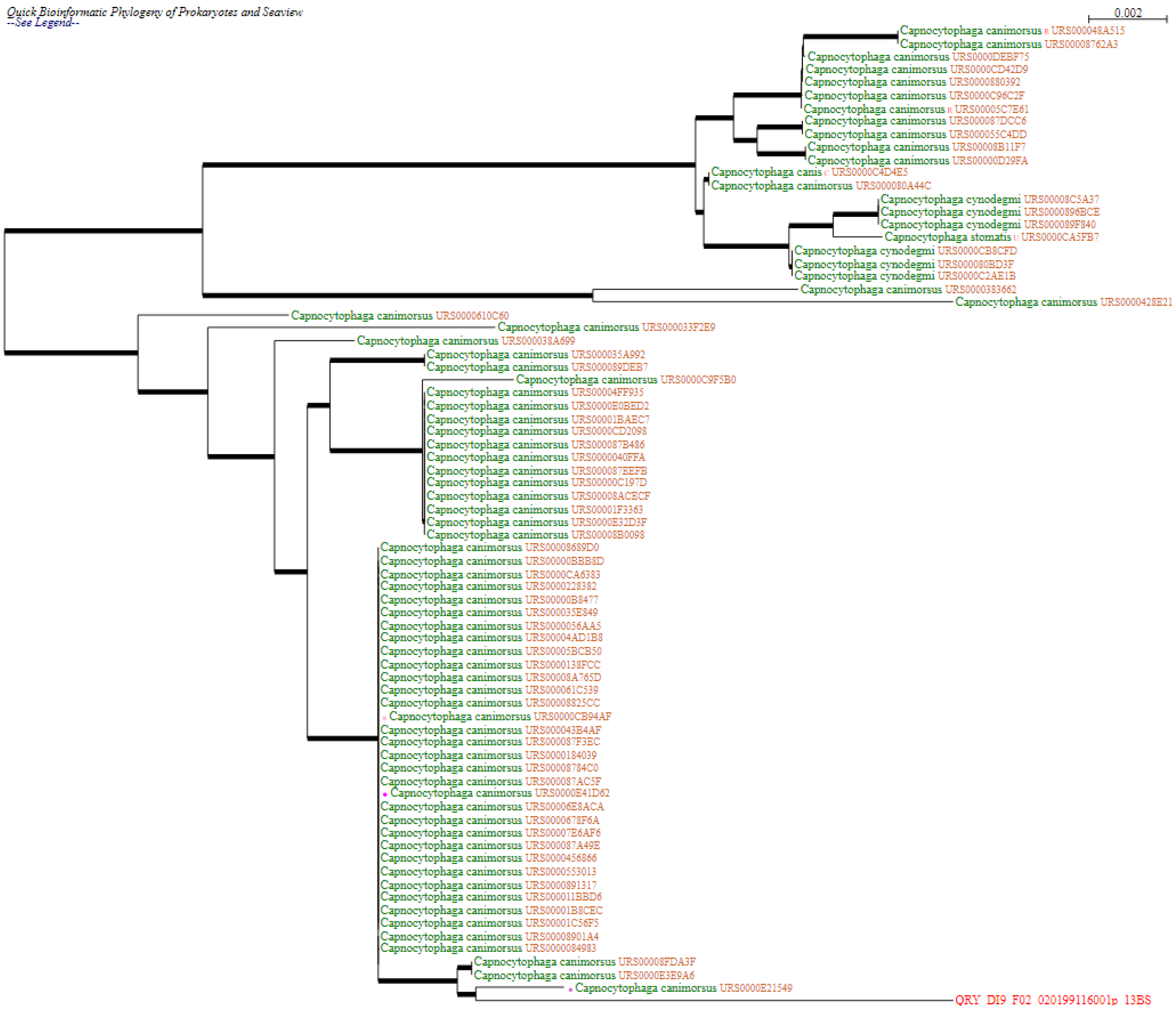

Case report

Discussion

Conclusions

Funding

Author contribution

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- Gaastra, W.; Lipman, L.J. Capnocytophaga canimorsus. Vet Microbiol. 2010, 140, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vignon, G.; Combeau, P.; Violette, J.; et al. [A fatal septic shock due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus and review of literature]. Rev Med Interne. 2018, 39, 820–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westwell, A.J.; Kerr, K.; Spencer, M.B.; Hutchinson, D.N. DF-2 infection. BMJ. 1989, 298, 116–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oelher, R.L.; Velez, A.P.; Mizrachi, M.; Lamarche, J.; GompfS. Bite related and septic syndromes caused by cats and dogs. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009, 9, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouin, P.; Veber, B.; Collange, A.; Frebourg, N.; Dureuil, B. [An unusual aetiology for septic shock: Capnocytophaga canimorsus. Is always dog man’s best friend?]. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2004, 23, 1185–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taquin, H.; Roussel, C.; Roudière, L.; et al. Fatal infection caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017, 17, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lion, C.; Escande, F.; Burdin, J.C. Capnocytophaga canimorsus infections in human: Review of the literature and cases report. Eur J Epidemiol. 1996, 12, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, H.; Mally, M.; Kuhn, M.; Paroz, C.; Cornelis, G.R. Escape from immune surveillance by Capnocytophaga canimorsus. J Infect Dis. 2007, 195, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mally, M.; Shin, H.; Paroz, C.; Landmann, R.; Cornelis, G.R. Capnocytophaga canimorsus: A human pathogen feeding at the surface of epithelial cells and phagocytes. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4, e1000164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hack, K.; Renzi, F.; Hess, E.e.t. al. Inactivation of human coagulation factor X by a protease of the pathogen Capnocytophaga canimorsus. J Thromb Haemost. 2016, 15, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uçkay, I.; Stirnemann, J. Exanthema associated with Capnocytophaga canimorsus bacteremia. Int J Infect Dis. 2019, 82, 104–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© GERMS 2022.

Share and Cite

Bergon, L.; Foissac, M.; Rivière, B.; Steinbach, M.I.; Catala, B.; Khatibi, S.; Souche, A.; Pirovano, L.; Condom, P.; Salama, G.; et al. Fatal Septic Shock Caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus Diagnosed by 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing. Germs 2022, 12, 124-129. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2022.1315

Bergon L, Foissac M, Rivière B, Steinbach MI, Catala B, Khatibi S, Souche A, Pirovano L, Condom P, Salama G, et al. Fatal Septic Shock Caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus Diagnosed by 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing. Germs. 2022; 12(1):124-129. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2022.1315

Chicago/Turabian StyleBergon, Ludovic, Maud Foissac, Brigitte Rivière, Marie Isabelle Steinbach, Bob Catala, Sarah Khatibi, Aubin Souche, Laure Pirovano, Pauline Condom, Gilles Salama, and et al. 2022. "Fatal Septic Shock Caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus Diagnosed by 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing" Germs 12, no. 1: 124-129. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2022.1315

APA StyleBergon, L., Foissac, M., Rivière, B., Steinbach, M. I., Catala, B., Khatibi, S., Souche, A., Pirovano, L., Condom, P., Salama, G., & Gilquin, J. (2022). Fatal Septic Shock Caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus Diagnosed by 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing. Germs, 12(1), 124-129. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2022.1315