Management of Antiretroviral Therapy with Boosted Protease Inhibitors—Darunavir/Ritonavir or Darunavir/Cobicistat

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Antiretroviral (ARV) Medication

- fixed dual combinations—emtricitabine/tenofovir, COBI/DRV, lamivudine/zidovudine, lopinavir/RTV, and abacavir/lamivudine;

- fixed triple combinations—abacavir/lamivudine/zidovudine and abacavir/lamivudine/dolutegravir;

- fixed quadruple combinations—elvitegravir/COBI/emtricitabine/tenofovir.

2.1. Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Protease

2.2. Protease Inhibitors (PIs)

3. Antiretroviral Therapy Resistance

Enzymatic Resistance to Protease Inhibitors

- Unique amino acid substitutions in the cavity of the active site of the enzyme, altering the size and shape of the side chains, which may alter the affinity of the drug and preserve the catalytic activity. The known mutations of this type are D30N, V32I, I47V, G48V, I50V, Val82, I84V, and G48T/L89M [43].

- Mutations that reduce the stability of the protease dimer, increasing dissociation between these portions and releasing limited inhibitor. The mutations associated with this mechanism are L24I, I50V, F53L, and Ile50 [44].

- Distal mutations, also related to PI resistance, may occur in different ways and may be difficult to detect, but may promote structural changes until the interaction with the inhibitor changes [37,45]. Distal mutations can also cooperate with active-site mutations to provide high PI resistance [46]. Examples of these mutations are L76 V [47,48] G73S [44], and N88D [49].

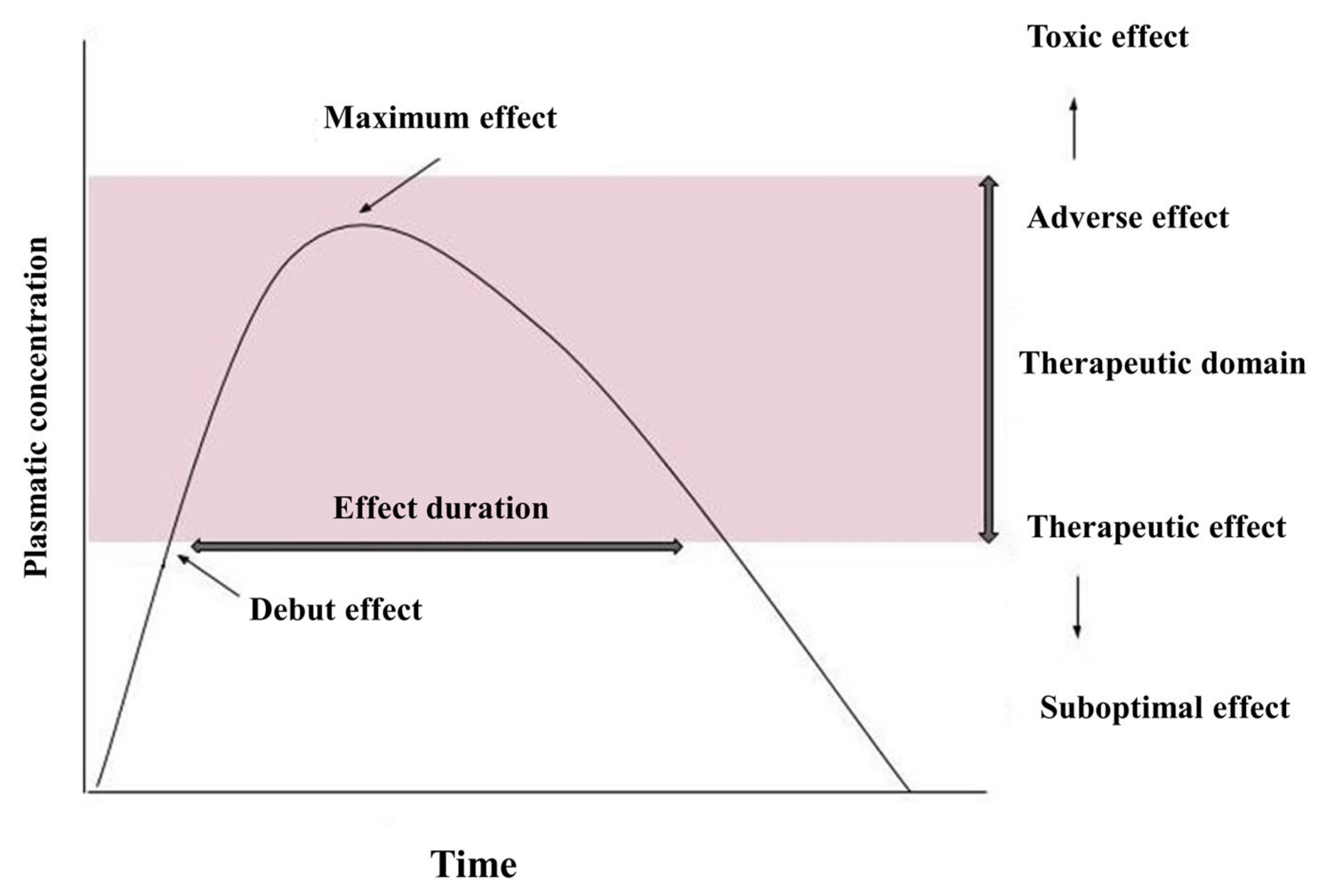

4. Pharmacokinetics of Antiretrovirals (ARVs)

4.1. Pharmacokinetics of Protease Inhibitors

4.1.1. Intrinsic Antiviral Activity

4.1.2. Residual Activity

4.1.3. Increased CD4 Levels

4.1.4. The Unique Features of PIs Are as Follows:

4.1.5. Entering Sanctuaries

4.1.6. Genetic Barrier Against Resistance

4.2. Efficiency of PIs, Compliance, and Survival

4.3. PI Side Effects

4.3.1. Insulin Resistance

4.3.2. Associated Metabolic Disorders

4.3.3. Lipodystrophy

4.3.4. Sexual Dysfunction

4.3.5. Hepatic Toxicity

- Mild to moderate increases in serum aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase levels that occur in a large proportion of patients taking ARV regimens containing PI. Moderate to severe increases in serum aminotransferase levels (above five times the upper normal limit) are found in 2% to 18% of patients, depending on the agent, the frequency of monitoring, and most importantly, the presence of virus coinfection with hepatitis B (HBV) or C (HCV). In HIV patients, without HCV or HBV infection (“mono infection”), increases in alanyl aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) are uncommon; levels of more than five times the upper normal limit were reported in only 1–4% of patients. These increases are usually asymptomatic and self-limiting and can be resolved even with continued medication. Therefore, this should not be a reason to discontinue the medication.

- Hyperbilirubinemia, without other manifestations of liver damage, is caused by the inhibition of glucuronyl transferase UDP, the liver enzyme responsible for conjugating bilirubin that is deficient in Gilbert’s syndrome. Hyperbilirubinemia is usually mild, averaging 0.9–1.5 mg/dL, but may be more severe in patients with Gilbert’s syndrome with increases of 2.5 mg/dL or more and clinical jaundice. Jaundice, however, does not indicate liver damage. However, jaundice caused by PIs can be painful for the patient and is a reason to discontinue treatment.

- Acute, idiosyncratic liver damage has been reported in most agents not very frequently. The few reported cases usually occurred within one to 12 weeks after starting therapy, and the pattern of serum enzyme growth ranged from hepatocellular to mixed and cholestatic. Signs of allergy or hypersensitivity (fever, rash, eosinophilia) may also occur as well as the appearance of autoantibodies. Acute liver damage from PIs is usually self-limiting but severe and isolated cases of acute liver failure have been reported, especially in patients with pre-existing underlying liver disease.

- Exacerbation of chronic underlying hepatitis B or C in co-infected individuals. Hepatitis usually occurs in 2–12 months after starting therapy, being associated with a hepatocellular pattern of serum enzyme growth, and also by increases, followed by decreases in the serum levels of HBV DNA or HCV RNA. These fluctuations can be severe, and even fatal cases have been reported [14].

5. Drug–Drug Interactions

5.1. Enzymatic Inhibition

5.2. Enzymatic Induction

6. Protease Inhibitors Enhancement

7. Pharmacokinetic Enhancers: Cobicistat (COBI) or Ritonavir (RTV)

- RTV, marketed as Norvir; it is included in Kaletra—lopinavir/RTV;

- COBI, commercially called Ybost; it comes in many combinations: atazanavir/COBI (Evotaz), elvitegravir/COBI/emtricitabine/tenofovir (Genvoya), DRV/COBI (Resolve), elvitegravir/covetousness/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil (Stribild), DRV/COBI/emtricitabine (Symtuza).

7.1. Ritonavir

7.1.1. Mechanism of Action

7.1.2. Pharmaceutical Form and Therapeutic Indications

7.1.3. Pharmacodynamic Properties

7.1.4. Pharmacokinetic Properties

7.1.5. Pharmaco-Toxicology

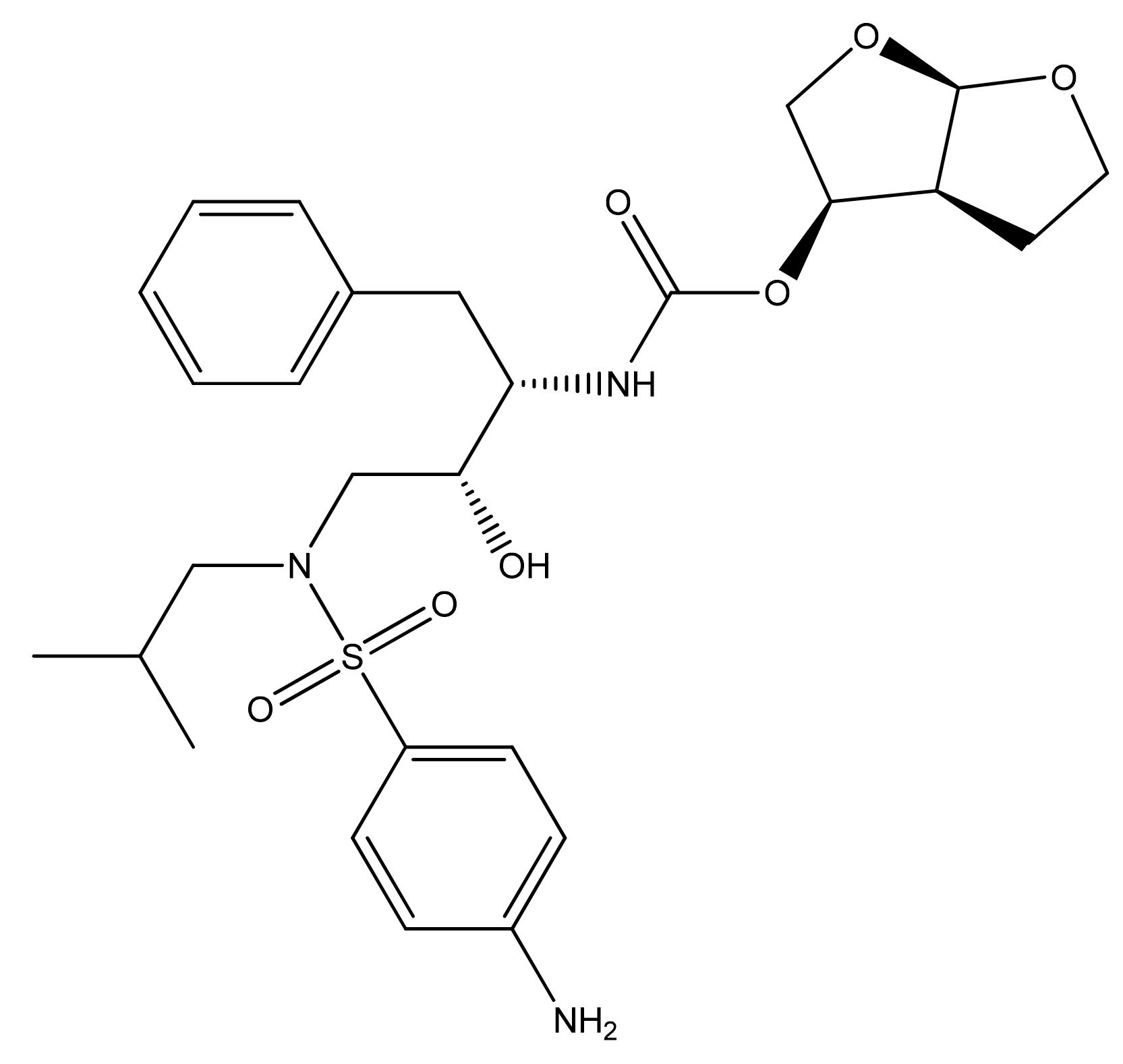

7.2. Cobicistat

7.2.1. Mechanism of Action and Therapeutic Effects

7.2.2. Pharmaceutical Form and Therapeutic Indications

7.2.3. Pharmacokinetic Properties

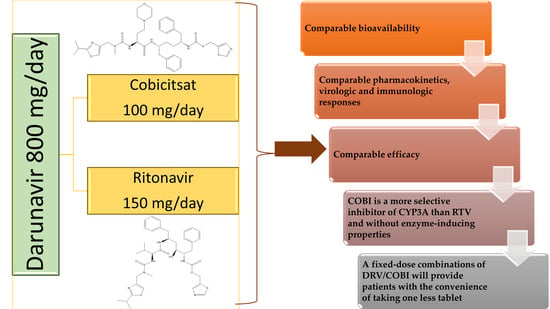

7.3. Similarities and Differences Between RTV and COBI

8. Protease Inhibitor—Darunavir

8.1. Pharmaceutical Form

8.2. Mechanism of Action

- have not been previously treated with ART; and

- have been previously treated with ART, have no DRV resistance mutations (DRV-RAMs) and have HIV-1 plasma RNA <100,000 copies/mL and CD4 + cell count ≥100 cells × 106/L. In deciding to start DRV treatment in these patients previously treated with ART, the administration should be guided by genotypic testing [150].

8.3. Pharmacodynamic Properties. Therapeutic Efficacy and Safety

8.4. Drug Resistance

8.5. Pharmacokinetic Properties

8.5.1. Absorption

8.5.2. Distribution

8.5.3. Drug Metabolism

8.5.4. Clearance

8.6. Pharmaco-Toxicology

8.7. Drug–Drug Interactions (DDI)

9. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Dakkak, I.; Patel, S.; McCann, E.; Gadkari, A.; Prajapati, G.; Maiese, E.M. The impact of specific HIV treatment-related adverse events on adherence to antiretroviral therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Care 2012, 25, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: A collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet 2008, 372, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Douce, V.; Janossy, A.; Hallay, H.; Ali, S.; Riclet, R.; Rohr, O.; Schwartz, C. Achieving a cure for HIV infection: Do we have reasons to be optimistic? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 1063–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mothi, S.; Swamy, V.; Sarvode, S.; Karpagam, S.; Mamatha, M.L. Paediatric HIV-trends & challenges. Indian, J. Med Res. 2011, 134, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drechsler, H.; Powderly, W.G. Switching Effective Antiretroviral Therapy: A Review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 35, 1219–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts, E.J.; Hazuda, D.J. HIV-1 Antiretroviral Drug Therapy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a007161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, G.H.; Zapor, M.J.; Smith, B.H.; Wortmann, G.; Oesterheld, J.R.; Armstrong, S.C.; Cozza, K.L. Antiretrovirals, Part 1: Overview, History, and Focus on Protease Inhibitors. Psychosomatics 2004, 45, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, N.E.; Emini, E.A.; Schleif, W.A.; Davis, L.J.; Heimbach, J.C.; Dixon, R.A.; Scolnick, E.M.; Sigal, I.S. Active human immunodeficiency virus protease is required for viral infectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1988, 85, 4686–4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lv, Z.; Chu, Y. HIV protease inhibitors: A review of molecular selectivity and toxicity. HIV/AIDS Res. Palliat. Care 2015, 7, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, E.P.; Kakuda, T.N.; Brundage, R.C.; Anderson, P.L.; Fletcher, C.V. Pharmacodynamics of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Protease Inhibitors. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2000, 30, S151–S159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arribas, J.R. Drugs in traditional drug classes (nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor/nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor/protease inhibitors) with activity against drug-resistant virus (tipranavir, darunavir, etravirine). Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2009, 4, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Summary for CID 392622, Ritonavir. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Ritonavir (accessed on 17 January 2021).

- Arasteh, K.; Yeni, P.; Pozniak, A.; Grinsztejn, B.; Jayaweera, D.; Roberts, A.; Hoy, J.; De Meyer, S.; Vangeneugden, T.; Tomaka, F. Efficacy and safety of darunavir/ritonavir in treatment-experienced HIV type-1 patients in the POWER 1, 2 and 3 trials at week 96. Antivir. Ther. 2009, 14, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protease Inhibitors (HIV). In LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2012.

- Brogan, A.; Mauskopf, J.; Talbird, S.E.; Smets, E. US Cost Effectiveness of Darunavir/Ritonavir 600/100mg bid in Treatment-Experienced, HIV-Infected Adults with Evidence of Protease Inhibitor Resistance Included in the TITAN Trial. Pharmacoeconomics 2010, 28, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotler, D.P. HIV and Antiretroviral Therapy: Lipid Abnormalities and Associated Cardiovascular Risk in HIV-Infected Patients. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2008, 49, S79–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bungau, S.; Behl, T.; Tit, D.M.; Banica, F.; Bratu, O.G.; Diaconu, C.C.; Nistor-Cseppento, C.D.; Bustea, C.; Aron, R.A.C.; Vesa, C.M. Interactions between leptin and insulin resistance in patients with prediabetes, with and without NAFLD. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesa, C.M.; Popa, L.; Popa, A.R.; Rus, M.; Zaha, A.A.; Bungau, S.; Tit, D.M.; Aron, R.A.C.; Zaha, D.C. Current Data Regarding the Relationship between Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddler, S.A.; Haubrich, R.; DiRienzo, A.G.; Peeples, L.; Powderly, W.G.; Klingman, K.L.; Garren, K.W.; George, T.; Rooney, J.F.; Brizz, B.; et al. Class-Sparing Regimens for Initial Treatment of HIV-1 Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 2095–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzette, S.A.; Ake, C.F.; Tam, H.K.; Chang, S.W.; Louis, T.A. Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Events in Patients Treated for Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hruz, P.W. HIV protease inhibitors and insulin resistance: Lessons from in-vitro, rodent and healthy human volunteer models. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2008, 3, 660–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soontornniyomkij, V.; Umlauf, A.; Chung, S.A.; Cochran, M.L.; Soontornniyomkij, B.; Gouaux, B.; Toperoff, W.; Moore, D.J.; Masliah, E.; Ellis, R.J.; et al. HIV protease inhibitor exposure predicts cerebral small vessel disease. AIDS 2014, 28, 1297–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, D.W.; Da Silva, B.A.; Arribas, J.R.; Myers, R.A.; Bellos, N.C.; Gilmore, N.; King, M.S.; Bernstein, B.M.; Brun, S.C.; Hanna, G.J. A 96-Week Comparison of Lopinavir-Ritonavir Combination Therapy Followed by Lopinavir-Ritonavir Monotherapy versus Efavirenz Combination Therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 2008, 198, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolta, S.; Flandre, P.; Van, P.N.; Cohen-Codar, I.; Valantin, M.-A.; Pintado, C.; Morlat, P.; Boué, F.; Rode, R.; Norton, M.; et al. Fat tissue distribution changes in HIV-infected patients treated with lopinavir/ritonavir. Results of the MONARK trial. Curr. HIV Res. 2011, 9, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuritzkes, D.R. Drug resistance in HIV-1. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2011, 1, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyon, L.; Croteau, G.; Thibeault, D.; Poulin, F.; Pilote, L.; Lamarre, D. Second locus involved in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to protease inhibitors. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 3763–3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammano, F.; Petit, C.; Clavel, F. Resistance-Associated Loss of Viral Fitness in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1: Phenotypic Analysis of Protease andgag Coevolution in Protease Inhibitor-Treated Patients. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 7632–7637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, M.A.; Merigan, T.C. Insertions in the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Protease and Reverse Transcriptase Genes: Clinical Impact and Molecular Mechanisms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 2575–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kožíšek, M.; Šašková, K.G.; Řezáčová, P.; Brynda, J.; Van Maarseveen, N.M.; De Jong, D.; Boucher, C.A.; Kagan, R.M.; Nijhuis, M.; Konvalinka, J. Ninety-Nine Is Not Enough: Molecular Characterization of Inhibitor-Resistant Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Protease Mutants with Insertions in the Flap Region. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 5869–5878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozal, M.J.; Shah, N.; Shen, N.; Yang, R.; Fucini, R.; Merigan, T.C.; Richman, D.D.; Morris, D.; Hubbell, E.; Chee, M.; et al. Extensive polymorphisms observed in HIV–1 clade B protease gene using high–density oligonucleotide arrays. Nat. Med. 1996, 2, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Conto, V.; Braz, A.S.; Perahia, D.; Scott, L.P. Recovery of the wild type atomic flexibility in the HIV-1 protease double mutants. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2015, 59, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, P.M.S.; Amano, M.; Yashchuk, S.; Mizuno, A.; Das, D.; Ghosh, A.K.; Mitsuya, H. GRL-04810 and GRL-05010, Difluoride-Containing Nonpeptidic HIV-1 Protease Inhibitors (PIs) That Inhibit the Replication of Multi-PI-Resistant HIV-1In Vitroand Possess Favorable Lipophilicity That May Allow Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 6110–6121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, M.; Garden, G.A.; Lipton, S.A. Pathways to neuronal injury and apoptosis in HIV-associated dementia. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001, 410, 988–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Yashchuk, S.; Mizuno, A.; Chakraborty, N.; Agniswamy, J.; Wang, Y.-F.; Aoki, M.; Gómez, P.M.S.; Amano, M.; Weber, I.T.; et al. Design of Gem-difluoro-bis-Tetrahydrofuran as P2-Ligand for HIV-1 Protease Inhibitors to Improve Brain Penetration: Synthesis, X-ray Studies, and Biological Evaluation. ChemMedChem 2014, 10, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, I.T.; Kneller, D.W.; Wong-Sam, A. Highly resistant HIV-1 proteases and strategies for their inhibition. Futur. Med. Chem. 2015, 7, 1023–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.D.; Schiffer, C.A.; Gonzales, M.J.; Taylor, J.; Kantor, R.; Chou, S.; Israelski, D.; Zolopa, A.R.; Fessel, W.J.; Shafer, R.W. Mutation Patterns and Structural Correlates in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Protease following Different Protease Inhibitor Treatments. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 4836–4847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henes, M.; Lockbaum, G.J.; Kosovrasti, K.; Leidner, F.; Nachum, G.S.; Nalivaika, E.A.; Lee, S.-K.; Spielvogel, E.; Zhou, S.; Swanstrom, R.; et al. Picomolar to Micromolar: Elucidating the Role of Distal Mutations in HIV-1 Protease in Conferring Drug Resistance. ACS Chem. Biol. 2019, 14, 2441–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, S.B.; Kent, S.J.; Winnall, W.R. The High Cost of Fidelity. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 2014, 30, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, D.L.; Swindells, S.; Mohr, J.; Brester, M.; Vergis, E.N.; Squier, C.; Wagener, M.M.; Singh, N. Adherence to Protease Inhibitor Therapy and Outcomes in Patients with HIV Infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 2000, 133, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, D.; Reiss, P.; Mallal, S. Adverse effects of antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection: A review of selected topics. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2005, 4, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramuto, F.; Bonura, F.; Mancuso, S.; Romano, N.; Vitale, F. Detection of a New 3-Base Pair Insertion Mutation in the Protease Gene of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 during Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART). AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 2005, 21, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira-Vaz, J.; Duque, V.; Trindade, L.; Saraiva-Da-Cunha, J.; Meliço-Silvestre, A. Detection of the protease codon 35 amino acid insertion in sequences from treatment-naïve HIV-1 subtype C infected individuals in the Central Region of Portugal. J. Clin. Virol. 2009, 46, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, N.E.; Ohanessian, M.; Biswas, S.; McGee, J.T.D.; Mahon, B.P.; Ostrov, D.A.; Garcia, J.; Tang, Y.; McKenna, R.; Roitberg, A.; et al. Defective Hydrophobic Sliding Mechanism and Active Site Expansion in HIV-1 Protease Drug Resistant Variant Gly48Thr/Leu89Met: Mechanisms for the Loss of Saquinavir Binding Potency. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, I.T.; Agniswamy, J. HIV-1 Protease: Structural Perspectives on Drug Resistance. Viruses 2009, 1, 1110–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kožíšek, M.; Henke, S.; Šašková, K.G.; Jacobs, G.B.; Schuch, A.; Buchholz, B.; Müller, V.; Kräusslich, H.-G.; Řezáčová, P.; Konvalinka, J.; et al. Mutations in HIV-1gagandpolCompensate for the Loss of Viral Fitness Caused by a Highly Mutated Protease. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 4320–4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtaka, H.; Schön, A.A.; Freire, E. Multidrug Resistance to HIV-1 Protease Inhibition Requires Cooperative Coupling between Distal Mutations. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 13659–13666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, J.M.; Zhang, Y.; Sayer, J.M.; Wang, Y.-F.; Harrison, R.W.; Weber, I.T. The L76V Drug Resistance Mutation Decreases the Dimer Stability and Rate of Autoprocessing of HIV-1 Protease by Reducing Internal Hydrophobic Contacts. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 4786–4795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragland, D.A.; Nalivaika, E.A.; Nalam, M.N.L.; Prachanronarong, K.L.; Cao, H.; Bandaranayake, R.M.; Cai, Y.; Kurt-Yilmaz, N.; Schiffer, C.A. Drug Resistance Conferred by Mutations Outside the Active Site through Alterations in the Dynamic and Structural Ensemble of HIV-1 Protease. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 11956–11963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-C.E.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tie, Y.; Wang, Y.-F.; Yashchuk, S.; Ghosh, A.K.; Harrison, R.W.; Weber, I.T. Potent Antiviral HIV-1 Protease Inhibitor GRL-02031 Adapts to the Structures of Drug Resistant Mutants with Its P1′-Pyrrolidinone Ring. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 3387–3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.; Baxter, J.D. Protease Inhibitor Resistance Update: Where Are We Now? AIDS Patient Care STDs 2008, 22, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wensing, A.M.; van Maarseveen, N.M.; Nijhuis, M. Fifteen years of HIV Protease Inhibitors: Raising the barrier to resistance. Antivir. Res. 2010, 85, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, J.G. Using Pharmacokinetics to Optimize Antiretroviral Drug-Drug Interactions in the Treatment of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2000, 30, S123–S129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Liu, H.; Murray, B.P.; Callebaut, C.; Lee, M.S.; Hong, A.; Strickley, R.G.; Tsai, L.K.; Stray, K.M.; Wang, Y.; et al. Cobicistat (GS-9350): A Potent and Selective Inhibitor of Human CYP3A as a Novel Pharmacoenhancer. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks, E.D. Darunavir: A Review of Its Use in the Management of HIV-1 Infection. Drugs 2013, 74, 99–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, C.K.; Martorell, C.; Ramgopal, M.; Laplante, F.; Fisher, M.; Post, F.A.; Liu, Y.; Curley, J.; Abram, M.E.; Custodio, J.; et al. Cobicistat-Boosted Protease Inhibitors in HIV-Infected Patients with Mild to Moderate Renal Impairment. HIV Clin. Trials 2014, 15, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, P.J.; Cretton-Scott, E.; Teague, A.; Wensel, T.M. Protease inhibitors for patients with HIV-1 infection: A comparative overview. Pharm. Ther. 2011, 36, 332–345. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, L.; Peterson, S.; Sedaghat, A.R.; McMahon, M.A.; Callender, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Pitt, E.; Anderson, K.S.; Acosta, E.P.; et al. Dose-response curve slope sets class-specific limits on inhibitory potential of anti-HIV drugs. Nat. Med. 2008, 14, 762–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Moing, V.; Thiébaut, R.; Chêne, G.; Leport, C.; Cailleton, V.; Michelet, C.; Fleury, H.; Herson, S.; Raffi, F.; for the APROCO Study Group. Predictors of Long-Term Increase in CD4+Cell Counts in Human Immunodeficiency Virus–Infected Patients Receiving a Protease Inhibitor–Containing Antiretroviral Regimen. J. Infect. Dis. 2002, 185, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ledergerber, B. Predictors of trend in CD4-positive T-cell count and mortality among HIV-1-infected individuals with virological failure to all three antiretroviral-drug classes. Lancet 2004, 364, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, R.; Katlama, C.; Murphy, R.L.; Squires, K.; Gatell, J.; Horban, A.; Clotet, B.; Staszewski, S.; Van Eeden, A.; Clumeck, N.; et al. A randomized trial to study first-line combination therapy with or without a protease inhibitor in HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS 2003, 17, 987–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, A.C.; Henley, W.E.; Donnelly, C.A.; Mayer, S.; Anderson, R.M. Comparison of the effectiveness of non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-containing and protease inhibitor-containing regimens using observational databases. AIDS 2001, 15, 1133–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podzamczer, D.; Ferrer, E.; Consiglio, E.; Gatell, J.M.; Perez, P.; Perez, J.L.; Luna, E.; González, A.; Pedrol, E.; Lozano, L.; et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing nelfinavir or nevirapine associated to zidovudine/lamivudine in HIV-infected naive patients (the Combine Study). Antivir. Ther. 2002, 7, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Benito, J.M.; López, M.; Martín, J.C.; Lozano, S.; Martínez, P.; González-Lahoz, J.; Soriano, V. Differences in Cellular Activation and Apoptosis in HIV-Infected Patients Receiving Protease Inhibitors or Nonnucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 2002, 18, 1379–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phenix, B.N.; Lum, J.J.; Nie, Z.; Sanchez-Dardon, J.; Badley, A.D. Antiapoptotic mechanism of HIV protease inhibitors: Preventing mitochondrial transmembrane potential loss. Blood 2001, 98, 1078–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, S.; Kodoth, S.; Pahwa, R.; Pahwa, S. The HIV protease inhibitor Indinavir inhibits cell-cycle progression in vitro in lymphocytes of HIV-infected and uninfected individuals. Blood 2001, 98, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Picado, J.; Savara, A.V.; Shi, L.; Sutton, L.; D’Aquila, R.T. Fitness of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Protease Inhibitor-Selected Single Mutants. Virology 2000, 275, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoddart, C.A.; Liegler, T.J.; Mammano, F.; Linquist-Stepps, V.D.; Hayden, M.S.; Deeks, S.G.; Grant, R.M.; Clavel, F.; McCune, J.M. Impaired replication of protease inhibitor-resistant HIV-1 in human thymus. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 712–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, B.M.; Letendre, S.L.; Brigid, E.; Clifford, D.B.; Collier, A.C.; Gelman, B.B.; McArthur, J.C.; McCutchan, J.A.; Simpson, D.M.; Ellis, R.; et al. Low atazanavir concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid. AIDS 2009, 23, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Montero, J.V.; Barreiro, P.; Soriano, V. HIV protease inhibitors: Recent clinical trials and recommendations on use. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2009, 10, 1615–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanger, U.M.; Schwab, M. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: Regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 138, 103–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.R.; Wynn, H.; Brundage, R.; Acosta, E.P.; Acosta, A.P.E.P. Pharmacokinetic Enhancement of Protease Inhibitor Therapy. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2004, 43, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeldin, R.K. Pharmacological and therapeutic properties of ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor therapy in HIV-infected patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003, 53, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, M.; Holmes, D. “So far it’s been choosing which side effects I want or I can deal with”: A grounded theory of HIV treatment side effects among people living with HIV. Aporia 2016, 8, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njuguna, C.; Stewart, A.; Mouton, J.P.; Blockman, M.; Maartens, G.; Swart, A.; Chisholm, B.; Jones, J.; Dheda, M.; Igumbor, E.U.; et al. Adverse Drug Reactions Reported to a National HIV & Tuberculosis Health Care Worker Hotline in South Africa: Description and Prospective Follow-Up of Reports. Drug Saf. 2016, 39, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permpalung, N.; Ungprasert, P.; Summachiwakij, S.; Leeaphorn, N.; Knight, E.L. Protease inhibitors and avascular necrosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2014, 44, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, R.; Sacchi, P.; Maiocchi, L.; Patruno, S.; Filice, G. Hepatotoxicity and antiretroviral therapy with protease inhibitors: A review. Dig. Liver Dis. 2006, 38, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pezzani, M.D.; Resnati, C.; Di Cristo, V.; Riva, A.; Gervasoni, C. Abacavir-induced liver toxicity. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 20, 502–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quatremère, G.; Guiguet, M.; Girardi, P.; Liaud, M.-N.; Mey, C.; Benkhoucha, C.; Barbier, F.; Cattaneo, G.; Simon, A.; Castro, D.R. How are women living with HIV in France coping with their perceived side effects of antiretroviral therapy? Results from the EVE study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filardi, P.P.; Paolillo, S.; Marciano, C.; Iorio, A.; Losco, T.; Marsico, F.; Scala, O.; Ruggiero, D.; Ferraro, S.; Chiariello, M. Cardiovascular effects of antiretroviral drugs: Clinical review. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Disord. Targets 2008, 8, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittar, R.; Aslangul, É.; Giral, P.; Assoumou, L.; Valantin, M.-A.; Kalmykova, O.; Federspiel, M.-C.; Cherfils, C.; Costagliola, D.; Bonnefont-Rousselot, D. Lack of effects of statins on high-density lipoprotein subfractions in HIV-1-infected patients receiving protease inhibitors. Comptes Rendus Biol. 2017, 340, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwiki, S.; Campos, M.M.; McLaughlin, M.E.; Kleiner, D.E.; Kovacs, J.A.; Morse, C.G.; Abu-Asab, M.S. Adverse effects of antiretroviral therapy on liver hepatocytes and endothelium in HIV patients: An ultrastructural perspective. Ultrastruct. Pathol. 2017, 41, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weldegebreal, F.; Mitiku, H.; Teklemariam, Z. Magnitude of adverse drug reaction and associated factors among HIV-infected adults on antiretroviral therapy in Hiwot Fana specialized university hospital, eastern Ethiopia. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2016, 24, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesson, J.; Dahourou, D.L.; Renaud, F.; Penazzato, M.; Leroy, V. Adverse events associated with abacavir use in HIV-infected children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV 2016, 3, e64–e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, N.S.; Peer, N.; Steyn, K.; Lombard, C.; Maartens, G.; Lambert, E.V.; Dave, J.A. Increased risk of dysglycaemia in South Africans with HIV; especially those on protease inhibitors. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pr. 2016, 119, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverría, P.; Bonjoch, A.; Puig, J.; Molto, J.; Paredes, R.; Sirera, G.; Ornelas, A.; Pérez-Álvarez, N.; Clotet, B.; Negredo, E. Randomised Study to Assess the Efficacy and Safety of Once-Daily Etravirine-Based Regimen as a Switching Strategy in HIV-Infected Patients Receiving a Protease Inhibitor–Containing Regimen. Etraswitch Study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e84676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, Y.; Nishijima, T.; Komatsu, H.; Teruya, K.; Gatanaga, H.; Kikuchi, Y.; Oka, S. Is Ritonavir-Boosted Atazanavir a Risk for Cholelithiasis Compared to Other Protease Inhibitors? PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Introcaso, C.E.; Hines, J.M.; Kovarik, C.L. Cutaneous toxicities of antiretroviral therapy for HIV: Part, I. Lipodystrophy syndrome, nucleoside reverse transcriptase in-hibitors, and protease inhibitors. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010, 63, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, N.M.; Ferreira, F.A.Y.; Yonamine, R.Y.; Chehter, E.Z. Antiretroviral drugs and acute pancreatitis in HIV/AIDS patients: Is there any association? A literature review. Einstein 2014, 12, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, R.; Teófilo, E. Antiretroviral therapy in treatment-naïve patients with HIV infection. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2011, 6, S3–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reust, C.E. Common adverse effects of antiretroviral therapy for HIV disease. Am. Fam. Physician 2011, 83, 1443–1451. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha-Hikim, A.P.; Mahata, S.K. Editorial: Obesity, Smoking, and Fatty Liver Disease. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, J.C.; Remedi, M.S.; Qiu, H.; Nichols, C.G.; Hruz, P.W. HIV protease inhibitors acutely impair glucose-stimulated insulin release. Diabetes 2003, 52, 1695–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesa, C.M.; Behl, T.; Nemeth, S.; Bratu, O.G.; Diaconu, C.C.; Moleriu, R.D.; Negrut, N.; Zaha, D.C.; Bustea, C.; Radu, F.I.; et al. Prediction of NAFLD occurrence in prediabetes patients. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchanda, T.; Schiedel, D.; Fischer, D.A.; Dekaban, G.; Rieder, M.J. Adverse drug reactions to protease inhibitors. Can. J. Clin. Pharmacol. J. Can. Pharmacol. Clin. 2002, 9, 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, D.; Bhatti, H.S.; Sehgal, R. Role of cholesterol in parasitic infections. Lipids Heal. Dis. 2005, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis-Møller, N.; Reiss, P.A.; Sabin, C.; Weber, R.; Monforte, A.D.; El-Sadr, W.; Thiebaut, R.; De Wit, S.; Kirk, O.; Fontas, E.E.; et al. Class of Antiretroviral Drugs and the Risk of Myocardial Infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1723–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.C.; Kingsley, L.A.; Sharrett, A.R.; Li, X.; Lazar, J.; Tien, P.C.; Mack, W.J.; Cohen, M.H.; Jacobson, L.; Gange, S.J. Ten-Year Predicted Coronary Heart Disease Risk in HIV-Infected Men and Women. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 45, 1074–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koethe, J.R. Adipose Tissue in HIV Infection. Compr. Physiol. 2017, 7, 1339–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, H.; Esch, L.D.; Morse, G.D. Glucose Disorders Associated with HIV and its Drug Therapy. Ann. Pharmacother. 2001, 35, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friis-Møller, N.; Weber, R.; Reiss, P.; Thiébaut, R.; Kirk, O.; Monforte, A.D.; Pradier, C.; Morfeldt, L.; Mateu, S.; Law, M.; et al. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in HIV patients—Association with antiretroviral therapy. Results from the DAD study. AIDS 2003, 17, 1179–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, D.Y. Effects of HIV protease inhibitor therapy on lipid metabolism. Prog. Lipid Res. 2003, 42, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monforte, A.D.; Lepri, A.C.; Rezza, G.; Pezzotti, P.; Antinori, A.; Phillips, A.N.; Angarano, G.; Colangeli, V.; De Luca, A.; Ippolito, G.; et al. Insights into the reasons for discontinuation of the first highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) regimen in a cohort of antiretroviral naïve patients. AIDS 2000, 14, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, S.; Spire, B.; Raffi, F.; Walter, V.; Bouhour, D.; Journot, V.; Cailleton, V.; Leport, C.; Moatti, J.-P. APROCO Cohort Study Group Self-Reported Symptoms After Initiation of a Protease Inhibitor in HIV-Infected Patients and Their Impact on Adherence to HAART. HIV Clin. Trials 2001, 2, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrooten, W.; Colebunders, R.; Youle, M.; Molenberghs, G.; Dedes, N.; Koitz, G.; Finazzi, R.; De Mey, I.; Florence, E.; Dreezen, C. Sexual dysfunction associated with protease inhibitor containing highly active antiretroviral treatment. AIDS 2001, 15, 1019–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallemand, F.; Salhi, Y.; Linard, F.; Giami, A.; Rozenbaum, W. Sexual Dysfunction in 156 Ambulatory HIV-Infected Men Receiving Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy Combinations With and Without Protease Inhibitors. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2002, 30, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lana, R.; Núñez, M.; Mendoza, J.L.; Soriano, V. Frecuencia y factores predictivos de hepatotoxicidad en pacientes que reciben terapia antirretroviral. Med. Clin. 2001, 117, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Fujii, T.; Mizoguchi, N.; Takata, N.; Ueda, K.; Feldman, M.D.; Kayser, S.R. Potential Interaction Between Ritonavir and Carbamazepine. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2000, 20, 851–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, C.B.; Vu, M.P.; Grunfeld, C.; Lampiris, H.W. Simvastatin-Nelfinavir Interaction Implicated in Rhabdomyolysis and Death. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 35, e111–e112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzeh, F.M.A.; Benson, C.; Gerber, J.G.; Currier, J.S.; McCrea, J.; Deutsch, P.J.; Ruan, P.; Wu, H.; Lee, J.; Flexner, C. Steady-state pharmacokinetic interaction of modified-dose indinavir and rifabutin. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003, 73, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, S.C.; Cozza, K.L. Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry Drug–Drug Interactions Update. J. Psychosom. Res. 2000, 41, 155–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perloff, M.D.; Von Moltke, L.L.; Marchand, J.E.; Greenblatt, D.J. Ritonavir induces P-glycoprotein expression, multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP1) expression, and drug transporter-mediated activity in a human intestinal cell line. J. Pharm. Sci. 2001, 90, 1829–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durant, J.; Clevenbergh, P.; Garraffo, R.; Halfon, P.; Icard, S.; Del Giudice, P.; Montagne, N.; Schapiro, J.M.; Dellamonica, P. Importance of protease inhibitor plasma levels in HIV-infected patients treated with genotypic-guided therapy: Pharmacological data from the Viradapt Study. AIDS 2000, 14, 1333–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, A.; Granneman, G.R.; Bertz, R.J. Ritonavir. Clinical pharmacokinetics and interactions with other anti-HIV agents. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1998, 35, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Liu, H.; Hong, A.; Vivian, R.; Murray, B.P.; Callebaut, C.; Choi, Y.-C.; Lee, M.S.; Chau, J.; Tsai, L.K.; et al. Structure–activity relationships of diamine inhibitors of cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A as novel pharmacoenhancers. Part II: P2/P3 region and discovery of cobicistat (GS-9350). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 995–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathias, A.A.; German, P.; Murray, B.P.; Wei, L.; Jain, A.; West, S.; Warren, D.; Hui, J.; Kearney, B.P. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of GS-9350: A Novel Pharmacokinetic Enhancer Without Anti-HIV Activity. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 87, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elion, R.; Cohen, C.; Gathe, J.; Shalit, P.; Hawkins, T.; Liu, H.C.; Mathias, A.A.; Chuck, S.L.; Kearney, B.P.; Warren, D.R. Phase 2 study of cobicistat versus ritonavir each with once-daily atazanavir and fixed-dose emtricitabine/tenofovir df in the initial treatment of HIV infection. AIDS 2011, 25, 1881–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakuda, T.N.; Opsomer, M.; Timmers, M.; Iterbeke, K.; Van De Casteele, T.; Hillewaert, V.; Petrovic, R.; Hoetelmans, R.M.W. Pharmacokinetics of darunavir in fixed-dose combination with cobicistat compared with coadministration of darunavir and ritonavir as single agents in healthy volunteers. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 54, 949–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, P.; Warren, D.; West, S.; Hui, J.; Kearney, B.P. Pharmacokinetics and Bioavailability of an Integrase and Novel Pharmacoenhancer-Containing Single-Tablet Fixed-Dose Combination Regimen for the Treatment of HIV. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2010, 55, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N.A.; Martin, J.A.; Kinchington, D.; Broadhurst, A.V.; Craig, J.C.; Duncan, I.B.; Galpin, S.A.; Handa, B.K.; Kay, J.; Krohn, A.; et al. Rational design of peptide-based HIV proteinase inhibitors. Science 1990, 248, 358–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renjifo, B.; van Wyk, J.; Salem, A.H.; Bow, D.; Ng, J.; Norton, M. Pharmacokinetic enhancement in HIV antiretroviral therapy: A comparison of ritonavir and cobicistat. AIDS Rev. 2015, 17, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Marzolini, C.; Gibbons, S.; Khoo, S.; Back, D. Cobicistat versus ritonavir boosting and differences in the drug–drug interaction profiles with co-medications. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 1755–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezolsta 800 mg/150 mg Film-Coated Tablets Darunavir/Cobicistat. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/rezolsta-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2021).

- Nathan, B.; Bayley, J.; Waters, L.; Post, F.A. Cobicistat: A Novel Pharmacoenhancer for Co-Formulation with HIV Protease and Integrase Inhibitors. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2013, 2, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, M.; Saag, M.; Powderly, W.G.; Hurley, A.M.; Hsu, A.; Valdes, J.M.; Henry, D.; Sattler, F.; La Marca, A.; Leonard, J.M.; et al. A Preliminary Study of Ritonavir, an Inhibitor of HIV-1 Protease, to Treat HIV-1 Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995, 333, 1534–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danner, S.A.; Carr, A.; Leonard, J.M.; Lehman, L.M.; Gudiol, F.; Gonzáles, J.; Raventos, A.; Rubio, R.; Bouza, E.; Pintado, V.; et al. A Short-Term Study of the Safety, Pharmacokinetics, and Efficacy of Ritonavir, an Inhibitor of HIV-1 Protease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995, 333, 1528–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norvir. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/209512lbl.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2021).

- Foisy, M.M.; Yakiwchuk, E.M.A.; Hughes, C. Induction Effects of Ritonavir: Implications for Drug Interactions. Ann. Pharmacother. 2008, 42, 1048–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.N.; Rodrigues, A.D.; Buko, A.M.; Denissen, J.F. Cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism of the HIV-1 protease in-hibitor ritonavir (ABT-538) in human liver microsomes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1996, 277, 423–431. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, Y.; Poblete, R.J.; Freilich, B.D.A.; Zarbin, M.; Bhagat, N. Retinal toxicity with Ritonavir. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 9, 640–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Summary for CID 25151504, Cobicistat. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Cobicistat (accessed on 17 January 2021).

- Cossu, M.V.; Astuti, N.; Capetti, A.; Rizzardini, G. Impact and differential clinical utility of cobicistat-boosted darunavir in HIV/AIDS. Virus Adapt. Treat. 2015, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tybost. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/tybost-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2021).

- Sherman, E.M.; Worley, M.V.; Unger, N.R.; Gauthier, T.P.; Schafer, J.J. Cobicistat: Review of a Pharmacokinetic Enhancer for HIV Infection. Clin. Ther. 2015, 37, 1876–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathias, A.; Murray, B.P.; Iwata, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Warren, D.; Kearney, B.P. Metabolism and Excretion in Humans of the Pharmacoenhancer GS-9350. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV Therapy, Sorrento, Italy, 7–9 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq, E. The Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors, Nonnucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors, and Protease Inhibitors in the Treatment of HIV Infections (AIDS). Adv. Pharmacol. 2013, 67, 317–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Hentig, N. Clinical use of cobicistat as a pharmacoenhancer of human immunodeficiency virus therapy. HIV/AIDS Res. Palliat. Care 2015, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepist, E.-I.; Phan, T.K.; Roy, A.; Tong, L.; MacLennan, K.; Murray, B.; Ray, A.S. Cobicistat Boosts the Intestinal Absorption of Transport Substrates, Including HIV Protease Inhibitors and GS-7340, in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 5409–5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, P.; Liu, H.C.; Szwarcberg, J.; Hepner, M.; Andrews, J.; Kearney, B.P.; Mathias, A. Effect of Cobicistat on Glomerular Filtration Rate in Subjects With Normal and Impaired Renal Function. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2012, 61, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepist, E.-I.; Zhang, X.; Hao, J.; Huang, J.; Kosaka, A.H.; Birkus, G.; Murray, B.P.; Bannister, R.; Cihlar, T.; Huang, Y.; et al. Contribution of the organic anion transporter OAT2 to the renal active tubular secretion of creatinine and mechanism for serum creatinine elevations caused by cobicistat. Kidney Int. 2014, 86, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallant, J.E.; Koenig, E.; Andrade-Villanueva, J.F.; Chetchotisakd, P.; DeJesus, E.; Antunes, F.; Arastéh, K.; Rizzardini, G.; Fehr, J.; Liu, H.C.; et al. Brief report: Cobicistat compared with Ritonavir as a pharmacoenhancer for Atazanavir in combination with Emtricita-bine/Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate: Week 144 results. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2015, 69, 338–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolson, A.H.; Wang, H. Regulation of drug-metabolizing enzymes by xenobiotic receptors: PXR and CAR. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2010, 62, 1238–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, R.F.; Gaver, V.E.; Patterson, K.B.; Rezk, N.L.; Baxter-Meheux, F.; Blake, M.J.; Eron, J.J.; Klein, C.E.; Rublein, J.C.; Kashuba, A.D. Lopinavir/Ritonavir Induces the Hepatic Activity of Cytochrome P450 Enzymes CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP1A2 But Inhibits the Hepatic and Intestinal Activity of CYP3A as Measured by a Phenotyping Drug Cocktail in Healthy Volunteers. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2006, 42, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, B.J.; Collier, A.C.; Kharasch, E.D.; Dixit, V.; Desai, P.; Whittington, D.; Thummel, K.E.; Unadkat, J.D. Complex Drug Interactions of HIV Protease Inhibitors 2: In Vivo Induction and In Vitro to In Vivo Correlation of Induction of Cytochrome P450 1A2, 2B6, and 2C9 by Ritonavir or Nelfinavir. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2011, 39, 2329–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Vousden, M.; Brittain, C.; McConn, D.J.; Iavarone, L.; Ascher, J.; Sutherland, S.M.; Muir, K.T. Dose-Related Reduction in Bupropion Plasma Concentrations by Ritonavir. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2010, 50, 1180–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Lee, M.J.; Dawood, L.; Ter Hofstede, H.J.; De Graaff-Teulen, M.J.; Kolmer, E.W.V.E.; Caliskan-Yassen, N.; Koopmans, P.P.; Burger, D.M. Lopinavir/ritonavir reduces lamotrigine plasma concentrations in healthy subjects. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006, 80, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, D.; Cossu, M.V.; Rizzardini, G. Pharmacokinetic drug evaluation of ritonavir (versus cobicistat) as adjunctive therapy in the treatment of HIV. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2019, 15, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeage, K.; Perry, C.M.; Keam, S.J. Darunavir: A review of its use in the management of HIV infection in adults. Drugs 2009, 69, 477–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, Y.; Matsumi, S.; Das, D.; Amano, M.; Davis, D.A.; Li, J.; Leschenko, S.; Baldridge, A.; Shioda, T.; Yarchoan, R.; et al. Potent Inhibition of HIV-1 Replication by Novel Non-peptidyl Small Molecule Inhibitors of Protease Dimerization. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 28709–28720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, N.M.; Prabu-Jeyabalan, M.; Nalivaika, E.A.; Wigerinck, P.; De Béthune, M.-P.; Schiffer, C.A. Structural and Thermodynamic Basis for the Binding of TMC114, a Next-Generation Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Protease Inhibitor. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 12012–12021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, C.; Perry, C.M. Darunavir: In the treatment of HIV-1 infection. Drugs 2007, 67, 2791–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzard, B.G.; Anderson, J.; Babiker, A.; Boffito, M.; Brook, G.; Brough, G.; Churchill, D.; Cromarty, B.; Das, S.; Fisher, M.; et al. British HIV Association Guidelines for the treatment of HIV-1-infected adults with antiretroviral therapy 2008. HIV Med. 2008, 9, 563–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, E.; González-Cordón, A.; Podzamczer, D.; Domingo, P.; Negredo, E.; Gutierrez, F.; Portilla, J.; Ribera, E.; Murillas, J.; Arribas, J.; et al. Metabolic effects of atazanavir/ritonavir vs darunavir/ritonavir in combination with tenofovir/emtricitabine in antiretroviral-naïve patients (ATADAR Study). J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2012, 15, 18202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakuda, T.N.; Brochot, A.; Tomaka, F.L.; Vangeneugden, T.; Van De Casteele, T.; Hoetelmans, R.M.W. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of boosted once-daily darunavir. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 2591–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violari, A.; Bologna, R.; Kumarasamy, N.; Pilotto, J.H.; Hendrickx, A.; Kakuda, T.N.; Lathouwers, E.; Opsomer, M.; Van de Casteele, T.; Tomaka, F.L. Safety and Efficacy of Darunavir/Ritonavir in Treatment-experienced Pediatric Patients. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2015, 34, e132–e137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violari, A.; Bologna, R.; Kimutai, R.; Kumarasamy, N.; Pilotto, J.H.; Hendrickx, A.; Kauwenberghs, G.; Lathouwers, E.; Van de Casteele, T.; Spinosa-Guzman, S. ARIEL: 24-week safety and efficacy of darunavir/ritonavir in treatment-experienced pediatric patients aged 3 to < 6 years. In Proceedings of the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Boston, MA, USA, 3–6 March 2014; p. 713. [Google Scholar]

- Beasley, N.; Thompson, A. Clinical Review. Pradaxa (Dabigatran). Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2010/022512orig1s000medr.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2021).

- Nivesanond, K.; Peeters, A.; Lamoen, D.; Van Alsenoy, C. Conformational Analysis of TMC114, a Novel HIV-1 Protease Inhibitor. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2007, 48, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierynck, I.; De Wit, M.; Gustin, E.; Keuleers, I.; Vandersmissen, J.; Hallenberger, S.; Hertogs, K. Binding Kinetics of Darunavir to Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Protease Explain the Potent Antiviral Activity and High Genetic Barrier. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 13845–13851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsuya, Y.; Liu, T.F.; Rhee, S.; Fessel, W.J.; Shafer, R.W. Prevalence of Darunavir Resistance–Associated Mutations: Patterns of Occurrence and Association with Past Treatment. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 196, 1177–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, V.; Kestens, D.; De Pauw, M.; De Paepe, E.; Vangeneugden, T.; Lefebvre, E.; Hoetelmans, R.M.W.; Spinosa-Guzman, S. The Effect of Different Meal Types on the Pharmacokinetics of Darunavir (TMC114)/Ritonavir in HIV-Negative Healthy Volunteers. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2007, 47, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, D.; Sekar, V.; Hoetelmans, R.M.W. Darunavir: Pharmacokinetics and drug interactions. Antivir. Ther. 2008, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Curran, A.; Gutirerrez, M.; Deig, E.; Mateo, G.; Lopez, R.M.; Imaz, A.; Crespo, M.; Ocaña, I.; Domingo, P.; Ribera, E. Efficacy, safety and pharmacokinetics of 900/100 mg of darunavir/ritonavir once daily in treatment-experienced patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 2195–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haubrich, R.; Berger, D.; Chiliade, P.; Colson, A.; Conant, M.; Gallant, J.; Wilkin, T.; Nadler, J.; Pierone, G.; Saag, M.; et al. Week 24 efficacy and safety of TMC114/ritonavir in treatment-experienced HIV patients. AIDS 2007, 21, F11–F18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arribas, J.; Clumeck, N.; Nelson, M.; Hill, A.; Delft, Y.; Moecklinghoff, C. The MONET trial: Week 144 analysis of the efficacy of darunavir/ritonavir (DRV/r) monotherapy versus DRV/r plus two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, for patients with viral load <50 HIV-1 RNA copies/mL at baseline. HIV Med. 2012, 13, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meyer, S.; Azijn, H.; Surleraux, D.; Jochmans, D.; Tahri, A.; Pauwels, R.; Wigerinck, P.; De Béthune, M.-P. TMC114, a Novel Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Protease Inhibitor Active against Protease Inhibitor-Resistant Viruses, Including a Broad Range of Clinical Isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 2314–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TMC114-TiDP29-C169: Bioavailability and Pharmacokinetics Trial Comparing Darunavir Pediatric Suspension Formulation to Current Darunavir Tablet. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00752310#moreinfo (accessed on 17 January 2021).

- Molina, J.-M.; Hill, A. Darunavir (TMC114): A new HIV-1 protease inhibitor. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2007, 8, 1951–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, V.J.; Lefebvre, E.; De Paepe, E.; De Marez, T.; De Pauw, M.; Parys, W.; Hoetelmans, R.M.W. Pharmacokinetic Interaction between Darunavir Boosted with Ritonavir and Omeprazole or Ranitidine in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Negative Healthy Volunteers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 958–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sekar, V.J.; Lefebvre, E.; De Pauw, M.; Vangeneugden, T.; Hoetelmans, R.M. Pharmacokinetics of darunavir/ritonavir and ketoconazole following co-administration in HIV-healthy volunteers. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 66, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, V.J.; Paepe, E.D.; Pauw, M.D.; Vangeneugden, T.; Lefebvre, E.; Hoetelmans, R.M.W.; Spinosa-Guzman, S. Darunavir/Ritonavir Pharmacokinetics Following Coadministration With Clarithromycin in Healthy Volunteers. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 48, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, V.J.; De Pauw, M.; Mariën, K.; Peeters, M.; Lefebvre, E.; Hoetelmans, R.M.W. Pharmacokinetic interaction between TMC114/r and efavirenz in healthy volunteers. Antivir. Ther. 2007, 12, 509–514. [Google Scholar]

- Katlama, C.; Esposito, R.; Gatell, J.M.; Goffard, J.-C.; Grinsztejn, B.; Pozniak, A.; Rockstroh, J.; Stoehr, A.; Vetter, N.; Yeni, P.; et al. Efficacy and safety of TMC114/ritonavir in treatment-experienced HIV patients: 24-week results of POWER 1. AIDS 2007, 21, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clotet, B.; Bellos, N.; Molina, J.-M.; Cooper, D.; Goffard, J.-C.; Lazzarin, A.; Wöhrmann, A.; Katlama, C.; Wilkin, T.; Haubrich, R.; et al. Efficacy and safety of darunavir-ritonavir at week 48 in treatment-experienced patients with HIV-1 infection in POWER 1 and 2: A pooled subgroup analysis of data from two randomised trials. Lancet 2007, 369, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katlama, C.; Bellos, N.; Grinsztejn, B.; Lazzarin, A.; Pozniak, A.; De Meyer, S.; Van De Casteele, T.; Spinosa-Guzman, S. POWER 1 and 2: Combined final 144-week efficacy and safety results for darunavir/ritonavir (DRV/r) 600/100 mg BID in treatment-experienced HIV patients. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2008, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, M.; Lachau-Durand, S.; Mannens, G.; Cuyckens, F.; Van Hoof, B.; Raoof, A. Absorption, Metabolism, and Excretion of Darunavir, a New Protease Inhibitor, Administered Alone and with Low-Dose Ritonavir in Healthy Subjects. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2009, 37, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darunavir Side Effects. Available online: https://www.drugs.com/sfx/darunavir-side-effects.html#moreResources (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Sharma, P.; Garg, S. Pure drug and polymer based nanotechnologies for the improved solubility, stability, bioavailability and targeting of anti-HIV drugs. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2010, 62, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofotokun, I.; Na, L.H.; Landovitz, R.J.; Ribaudo, H.J.; Mccomsey, G.A.; Godfrey, C.; Aweeka, F.; Cohn, S.E.; Sagar, M.; Kuritzkes, D.R.; et al. Comparison of the metabolic effects of ritonavir-boosted darunavir or atazanavir versus raltegravir, and the impact of ritonavir plasma exposure: ACTG 5257. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 60, 1842–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, J.C.R.; D’Arcy, D.M.; Serra, C.H.D.R.; Salgado, H.R.N. Darunavir: A Critical Review of Its Properties, Use and Drug Interactions. Pharmacology 2012, 90, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antiretrovirals: HIV and AIDS Drugs. Available online: https://www.webmd.com/hiv-aids/aids-hiv-medication (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Busse, K.H.S.; Penzak, S.R. Darunavir: A second-generation protease inhibitor. Am. J. Health Pharm. 2007, 64, 1593–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holodniy, M. Darunavir in the treatment of HIV-1 infection: A viewpoint by Mark Holodniy. Drugs 2007, 67, 2802–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCoy, C. Darunavir: A Nonpeptidic Antiretroviral Protease Inhibitor. Clin. Ther. 2007, 29, 1559–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwo, B.O.; Hicks, C.B. Darunavir: An overview of an HIV protease inhibitor developed to overcome drug resistance. AIDS Read. 2007, 17, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Warnke, D.; Barreto, J.; Temesgen, Z. Antiretroviral Drugs. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2007, 47, 1570–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rittweger, M.; Arastéh, K. Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Darunavir. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2007, 46, 739–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drug Interactions with Darunavir (TMC-114). Available online: https://i-base.info/htb/2892 (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Mathias, A.; Liu, H.C.; Warren, D.; Sekar, V.; Kearney, B.P. Relative Bioavailability and Pharmacokinetics of Darunavir when boosted with the Pharmacoenhancer GS-9350 versus Ritonavir. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV Therapy, Sorrento, Italy, 7–9 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

| Amino Acids of Chain A | Ligand-Protein Distance (Å) | Types of Connections | Amino Acids of Chain B | Ligand-Protein Distance (Å) | Types of Connections |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALA28 | 4.43 | π-alkyl | ALA82 | 4.38 | Π–alkyl |

| PRO81 | 4.39 | PRO81 | 5.47 | ||

| ILE47 | 4.90 | ILE84 | 5.37 | ||

| ALA82 | 4.35 | 4.24 | Alkyl | ||

| 4.98 | ALA28 | 4.24 | |||

| 4.26 | Alkyl | 3.81 | |||

| ILE50 | 4.43 | VAL32 | 4.97 | ||

| GLY48 | 3.68 | C-H | 5.39 | ||

| ASP30 | 2.58 | GLY27 | 3.05 | H bond | |

| ASP25 | 2.64 | H bond | ASP25 | 2.71 | |

| 2.79 | 2.75 | ||||

| ARG8 | 3.13 | π-cation | GLY48 | 3.33 | |

| 3.39 | C–H | ||||

| ASP29 | 2.96 | ||||

| 2.80 | H bond | ||||

| GLY49 | 3.29 | C–H | |||

| COBI | RTV |

|---|---|

| Similar Actions | |

| Potency on CYP 3A4 [137]. At therapeutic conc., inhibitory effect on the hepatic organic anions’ transporters of OATP polypeptides and MATE1 [116]. Inhibitory effect on the intestinal transporters P-gp and BCRP, thus increasing the absorption of co-administered substances [138]. Determine a slight increase in SCR and an associated decrease in glomerular filtration rate (reported in patients with RTV or COBI regimen included), mainly due to the inhibition of CR secretion, by inhibition of MATE1, and not due to impaired liver function [116,120,139,140]. Activate more or less PXR (which regulates the expression of various enzymes that metabolize drug substances) [142]. | |

| Different Actions | |

| More selective, at clinically relevant conc. [139]. No inhibitory effects on CYP 2C8 and slightly inhibits CYP 2D6 [138]. Increases SCR conc. (higher SCR levels than in patients with RTV-containing regimens) [116,120,139,140]. Active transporter in tubular cells, with OCT2; higher SCR levels mentioned above are explained by the fact that COBI preferentially accumulates in tubular cells and reaches conc. capable of inhibiting MATE1 [53,141]. Limited effect on PXR, being unlikely to have an enzymatic induction effect on drug metabolism [143,144,145] Less pill burden (available at single tablet regimen) [146]. Neutral effects on serum lipids [146]. Higher risk of DDIs in association with antithrombotic [146]. Contraindicated in HIV-infected pregnant women [146]. | Activates PXR and induces CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and glucuronidation enzymes [143,144,145]. Higher potency for CYP 3A inhibition [136,137,146]. Fine tuning of individualized ARV regimens in patients with polytherapy [146]. Detrimental effects on serum lipids [146]. Higher risk of DDIs with non-CYP 3A substrates (considering party drugs as well) [146]. Recommended in HIV-infected pregnant women [146]. |

| Amino Acids of Chain A | Ligand-Protein Distance (Å) | Types of Connections | Amino Acids of Chain B | Ligand-Protein Distance (Å) | Types of Connections |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASP30 | 3.32 | H bond | GLY49 | 3.01 | C-H |

| ASP25 | 2.92 | GLY27 | 3.31 | ||

| ASP29 | 2.89 | ILE47 | 5.08 | π-alkyl | |

| 3.20 | PRO81 | 4.99 | |||

| GLY27 | 3.33 | H bond | ALA28 | 4.11 | |

| 3.67 | C-H | VAL82 | 3.44 | π-sigma | |

| ILE50 | 5.04 | π-alkyl | ASP30 | 3.31 | H bound |

| ALA28 | 4.60 | Alkyl | |||

| VAL82 | 5.38 | ||||

| ILE47 | 5.07 | ||||

| Adverse Effect/Ref. | DRV/COBI | DRV/RTV |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal [122,150,160,172,173,180,181,182,183,184,185] | v diarrhea 28%, nausea 23% c vomiting, abdominal pain, abdominal distension, dyspepsia, flatulence, increased pancreatic enzymes u acute pancreatitis | v diarrhea 14.4% c nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, increased pancreatic amylase, increased pancreatic lipase, abdominal distension, dyspepsia, flatulence, increased serum amylase u pancreatitis, gastritis, gastroesophageal reflux, stomatitis, dry mouth, abdominal discomfort, constipation, increased lipase, belching r stomatitis, hematemesis, cheilitis, dry lips, loaded tongue f increase in liver enzymes |

| Others [122,160,172,180,181,182,183,184,185,186] | v fatigue u asthenia | v increase: cholesterol 10–25%, LDL 9.12–14.4%, TG 3.9–10.4%, alkaline phosphatase 1–3.9% c asthenia, fatigue u fever, chest pain, peripheral edema, redness, general malaise, pain, weight loss or gain, HDL decrease, increase in serum alkaline phosphatase, increase in lactate dehydrogenase. r chills, xerosis f hypertension, facial edema, decreased bicarbonate |

| Dermatological—rashes generally mild and moderate, appear in the first 4 weeks of treatment, are remitted to continuous administration [122,150,160,180,183,185] | v maculopapular rash, papular, erythematous, pruritic, generalized rash, allergic dermatitis—16% c angioedema, pruritus, urticaria | c macular, maculopapular, papular, erythematous, pruritic rash, pruritus, lipodystrophy—lipo-hypertrophy, lipodystrophy, lipoatrophy u angioedema, generalized rash, urticaria, night sweats, allergic dermatitis, eczema, erythema, alopecia, hyperhidrosis, Steven-Johnson syndrome, acne, dry skin, nail pigmentation, herpes simplex infection, severe skin reactions accompanied or not by fever and/or increased transaminases r drug eruptions with eosinophilia, systemic symptoms, erythema multiforme, dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, skin lesions, xeroderma f folliculitis, lipoatrophy, toxic skin rash, drug dermatitis, skin inflammation |

| Metabolic: high glucose levels, grade 2 (up to 15.4%), grade 3 (to 1.7%), grade 4 (<1%), were reported to co-administer DRV/RTV [122,160,180,181,182,183,184,185,186] | c anorexia, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, hyperlipidemia | v elevated glucose levels up to 15.4% c hyperlipidemia, anorexia, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, hyper triglyceridemia u gout, decreased or increased appetite, polydipsia, hyperglycemia, insulin resistance f hypoglycemia, hyperuricemia, hypocalcemia, hyponatremia, obesity, hypoalbuminemia |

| Nervous system [122,180,183,185] | v headache | c headache, diabetic neuropathy, dizziness u lethargy, hypoesthesia, paresthesia, dysgeusia, attention and memory disorders, drowsiness and vertigo r convulsions, syncope, agitation, sleep disturbances f transient ischemic attack, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy |

| Liver [122,150,173,180,181,183,184,185] | v increase in liver enzymes | c increase in alanyl amino-transferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) u hepatitis, acute hepatitis, cytolytic hepatitis, hepatic steatosis, hepatotoxicity, increased transaminases, serum bilirubin and gamma-glutamyl transferase f increase in liver enzymes |

| Psychiatric [122,180,183,185] | c abnormal dreams | c insomnia. u depression, disorientation, sleep disturbances, abnormal dreams, nightmares, anxiety, decreased libido, irritability r confusion, unchanged mood, restlessness |

| Cardio-vascular [122,180,183,185] | u myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, QT prolongation, ECG prolongation, tachycardia, hypertension r acute myocardial infarction, sinus bradycardia, palpitations | |

| Blood [122,180,181,183,185] | u thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, anemia, leukopeni. | |

| Kidneys [122,180,183,185] | c increase in blood creatinine | u acute renal failure, renal failure, nephrolithiasis, increased blood creatinine r decreased renal creatinine clearance f renal failure |

| Musculoskeletal [122,180,183,185] | c myalgia | u myalgia, osteonecrosis, muscle spasms, muscle weakness, arthralgia, extremity pain, osteoporosis, increased creatine phosphokinase in the blood r musculoskeletal stiffness, arthritis, joint stiffness f osteopenia |

| Respiratory [122,173,180,183,185] | u dyspnea, cough, epistaxis, sore throat r rhinorrhea f nasopharyngitis, hiccups, pneumonia, upper respiratory tract infections | |

| Hypersensitivity reaction [122,180,181,183,185] | c drug hypersensitivity | u drug hypersensitivity |

| Genitourinary [122,180,183,185] | u proteinuria, bilirubinuria, dysuria, nocturia, pollakiuria, erectile dysfunction f polyuria | |

| Immunological [122,180,183,185] | u inflammatory syndrome of immune reconstitution | u inflammatory syndrome of immune reconstitution |

| Endocrine [122,180,181,183,185] | u hypothyroidism, increased levels of thyroid hormone in the blood, gynecomastia | |

| Eye [122,180,183,185] | u conjunctival hyperemia, dry eye sensation r visual disturbances |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marin, R.-C.; Behl, T.; Negrut, N.; Bungau, S. Management of Antiretroviral Therapy with Boosted Protease Inhibitors—Darunavir/Ritonavir or Darunavir/Cobicistat. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 313. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9030313

Marin R-C, Behl T, Negrut N, Bungau S. Management of Antiretroviral Therapy with Boosted Protease Inhibitors—Darunavir/Ritonavir or Darunavir/Cobicistat. Biomedicines. 2021; 9(3):313. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9030313

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarin, Ruxandra-Cristina, Tapan Behl, Nicoleta Negrut, and Simona Bungau. 2021. "Management of Antiretroviral Therapy with Boosted Protease Inhibitors—Darunavir/Ritonavir or Darunavir/Cobicistat" Biomedicines 9, no. 3: 313. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9030313

APA StyleMarin, R.-C., Behl, T., Negrut, N., & Bungau, S. (2021). Management of Antiretroviral Therapy with Boosted Protease Inhibitors—Darunavir/Ritonavir or Darunavir/Cobicistat. Biomedicines, 9(3), 313. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9030313