Immunogenicity in Fabry Disease: Current Issues, Coping Strategies, and Future Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Challenging Questions and Evidence-Based Answers

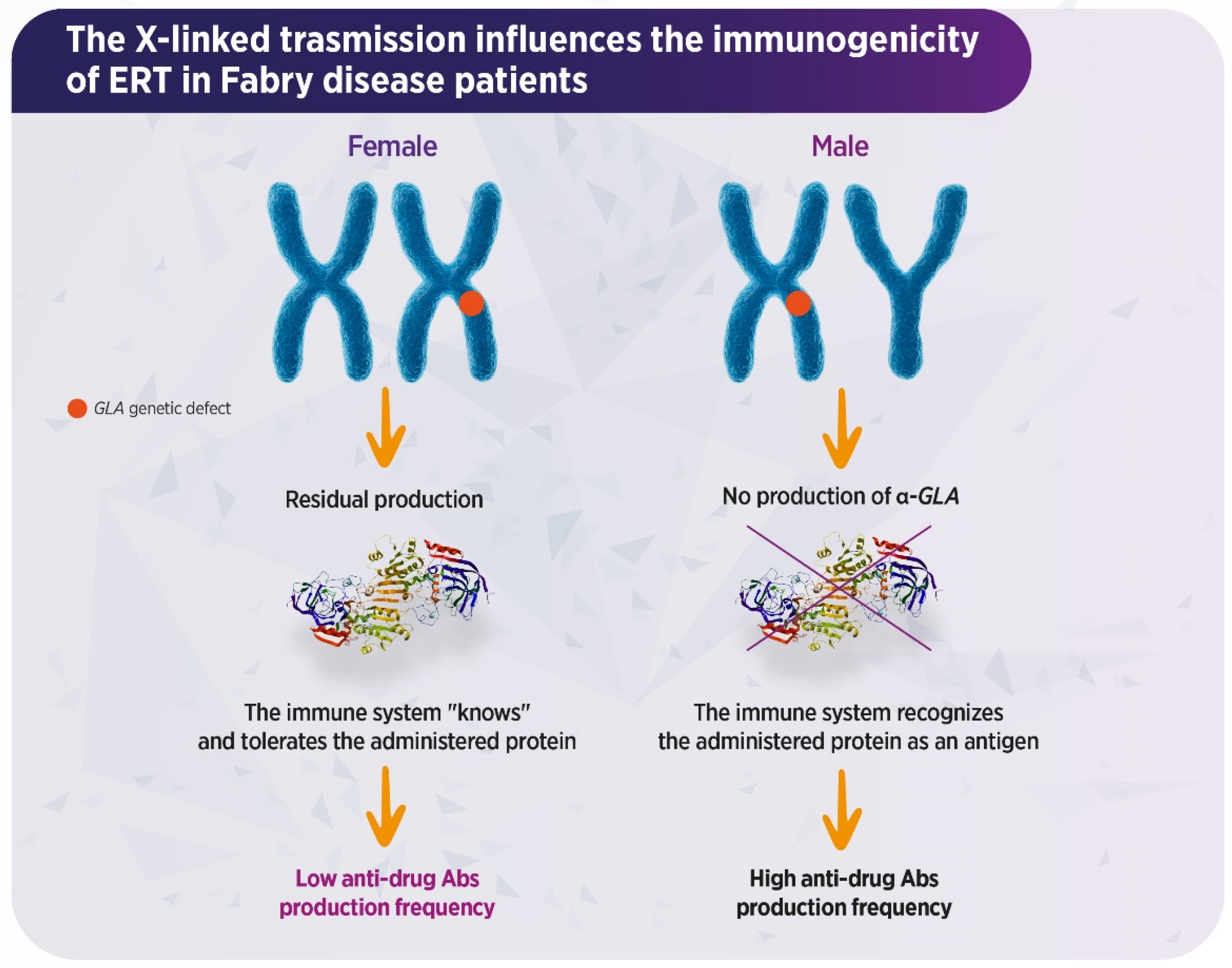

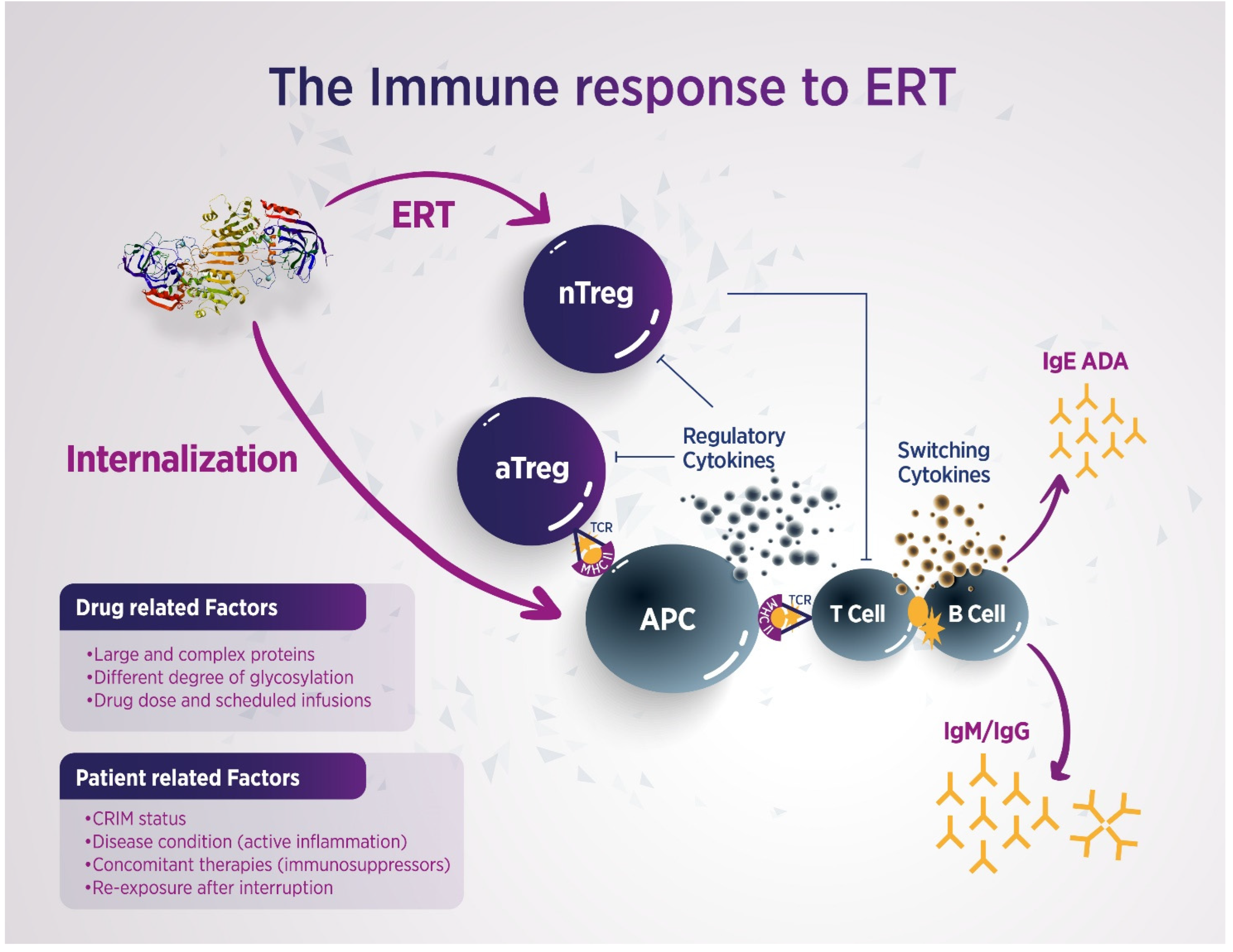

2.1. Which Factors Are More Likely to Predispose to ADAs Development During ERT Administration in FD Patients?

2.2. Is There Any Difference in ADA Formation Related to the Type of ERT Used?

2.3. What Is the Relationship Between ADA Production and IRRs?

2.4. What Is the Impact of Anti-Agalsidase Antibodies on FD Biomarkers and Overall ERT Effectiveness?

3. Available Strategies to Mitigate and Overcome Immunogenicity

3.1. Can Dose Escalation Overcome ADAs Production in the Course of ERT?

3.2. What Protocols Are Currently Being Assessed to Control Immunogenicity in FD?

- Immunoadsorption (IA) protocols based on non-specific IgG depletion have proven highly effective in various clinical settings, including myasthenia gravis, kidney and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and autoimmune dilated cardiomyopathy [59,60,61]. While non-specific IA systems remove total Ig fractions, potentially weakening the overall humoral immune response, antigen-specific IA selectively depletes pathogenic antibodies without affecting other antibody populations or compromising the immune system [62]. In FD, the application of IA is still in the preclinical phase. Lenders et al. demonstrated in vitro that AGAL-specific ADAs can be selectively removed from the sera of FD patients. However, titers appear to recover rapidly, suggesting that high-frequency IA treatments would be necessary [63].

- The effectiveness of immunosuppressive (IS) therapy in improving outcomes of ERT in LSDs has been previously documented. It has been shown that immune tolerance can be achieved when IS treatment is initiated prior to or simultaneously with ERT. Clinical experience from other disorders treated with recombinant proteins demonstrates that, once ADAs develop, especially at high titers, they tend to persist, despite IS interventions [64]. Banugaria et al. reported that immune tolerance induction using rituximab, methotrexate, and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) enhanced ERT efficacy in CRIM-negative infantile-onset Pompe disease [65]. However, it is noteworthy that, recently, anti-rituximab antibodies have been described in patients with membranous glomerulonephritis treated with rituximab and associated with less therapeutic effectiveness [66]. Dickson et al. documented benefits in a canine MPS-1 model using azathioprine and cyclosporine in combination with ERT [67]. However, because rituximab does not deplete memory B cells, additional administration of bortezomib effectively reduces ADA titers in infantile-onset Pompe disease [68,69]. Furthermore, pre-treatment with omalizumab has been shown to reduce IgE levels in FD patients [70]. While the global impact of antibodies on therapy remains partially understood, Garman et al. observed reduced antibody responses to agalsidase-β using 10 mg/kg methotrexate in a murine FD model [71]. More recent studies have shown that IS therapy, specifically with prednisolone, tacrolimus, and mycophenolate mofetil/mycophenolate acid, successfully eliminated antibody-mediated ERT inhibition in transplanted male FD patients. However, tapering IS therapy led to a recurrence of ERT inhibition, while higher IS doses correlated with lower ADA titers and reduced inhibition [72]. Therefore, IS therapy may serve as an effective approach to managing specific and clinically significant antibody responses over time. Nevertheless, the optimal IS regimen for preventing ADA formation in FD remains to be established, especially in patients with high levels of ERT inhibition, due to the potential adverse effects of IS agents. For these reasons, it might be advisable to modify the therapeutic scheme, i.e., prolonged half-life of infused enzymes, increased infusion frequencies with less enzyme concentrations, or reduced agalsidase-β infusion time, in order to minimize the need for IS interventions, even though the real effectiveness of these changes has not been definitively proven [72,73] (Table 4).

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADAs | Antidrug antibodies |

| APCs | Antigen-presenting cells |

| CHO | Chinese hamster ovary |

| CRIM | Cross-reactive immunologic material |

| eGFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| ERT | Enzyme replacement therapy |

| FOS | Fabry Outcome Survey |

| Gb3 | Globotriaosylceramide |

| GLA | α-galactosidase A |

| GSL | Glycosphingolipids |

| IA | Immunoadsorption |

| IAR | Immune adverse reaction |

| IRRs | Infusion-related reactions |

| IS | Immunosuppressive |

| IVIG | Intravenous immunoglobulin |

| LSD | Lysosomal storage disease |

| LysoGb3 | Globotriaosylsphingosine |

| M6P | Mannose-6-phosphate |

| NGNA | N-glycolylneuraminic acid |

| OS | Oxidative stress |

| PAF | Platelet activating factor |

| PMS | Post-marketing surveillance |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| RCTs | Randomized controlled trials |

| α-AGAL | α-galactosidase A |

References

- Wanner, C.; Arad, M.; Baron, R.; Burlina, A.; Elliott, P.M.; Feldt-Rasmussen, U.; Fomin, V.V.; Germain, D.P.; Hughes, D.A.; Jovanovic, A.; et al. European expert consensus statement on therapeutic goals in Fabry disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2018, 124, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squillaro, T.; Antonucci, I.; Alessio, N.; Esposito, A.; Cipollaro, M.; Melone, M.A.B.; Peluso, G.; Stuppia, L.; Galderisi, U. Impact of lysosomal storage disorders on biology of mesenchymal stem cells: Evidences from in vitro silencing of glucocerebrosidase (GBA) and alpha-galactosidase A (GLA) enzymes. J. Cell. Physiol. 2017, 232, 3454–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillo, R.; Graziani, F.; Franceschi, F.; Iannaccone, G.; Massetti, M.; Olivotto, I.; Crea, F.; Liuzzo, G. Inflammation across the spectrum of hypertrophic cardiac phenotypes. Heart Fail. Rev. 2023, 28, 1065–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenders, M.; Brand, E. Precision medicine in Fabry disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2021, 36, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, O.; Gago, M.F.; Miltenberger-Miltenyi, G.; Sousa, N.; Cunha, D. Fabry disease therapy: State-of-the-art and current challenges. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli, V.; Stamerra, C.A.; d’Angelo, M.; Cimini, A.; Ferri, C. Current and experimental therapeutics for Fabry disease. Clin. Genet. 2021, 100, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, S.; Atta, M.G. Therapeutic advances in Fabry disease: The future awaits. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 131, 110779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesi Global Rare Diseases; Protalix BioTherapeutics. FDA Approval of ELFABRIO® (pegunigalsidase alfa-iwxj) for the Treatment of Fabry Disease. Press Release, 2023. Available online: https://chiesirarediseases.com/media/fda-approval-of-elfabrio (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Hughes, D.A.; Bichet, D.G.; Giugliani, R.; Hopkin, R.J.; Krusinska, E.; Nicholls, K.; Olivotto, I.; Feldt-Rasmussen, U.; Sakai, N.; Skuban, N.; et al. Long-term multisystemic efficacy of migalastat on Fabry-associated clinical events. J. Med. Genet. 2023, 60, 722–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Veen, S.J.; Vlietstra, W.J.; van Dussen, L.; van Kuilenburg, A.B.P.; Dijkgraaf, M.G.W.; Lenders, M.; Brand, E.; Wanner, C.; Hughes, D.; Elliott, P.M.; et al. Predicting the development of antidrug antibodies against recombinant α-galactosidase A in male patients with classical Fabry disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauhin, W.; Lidove, O.; Masat, E.; Mingozzi, F.; Mariampillai, K.; Ziza, J.M.; Benveniste, O. Innate and adaptive immune response in Fabry disease. JIMD Rep. 2015, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smid, B.E.; Hoogendijk, S.L.; Wijburg, F.A.; Hollak, C.E.; Linthorst, G.E. A revised home treatment algorithm for Fabry disease: Influence of antibody formation. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2013, 108, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arends, M.; Biegstraaten, M.; Wanner, C.; Sirrs, S.; Mehta, A.; Elliott, P.M.; Oder, D.; Watkinson, O.T.; Bichet, D.G.; Khan, A.; et al. Agalsidase alfa versus agalsidase beta for the treatment of Fabry disease. J. Med. Genet. 2018, 55, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limgala, R.P.; Jennelle, T.; Plassmeyer, M.; Boutin, M.; Lavoie, P.; Abaoui, M.; Auray-Blais, C.; Nedd, K.; Alpan, O.; Goker-Alpan, O. Altered immune phenotypes in subjects with Fabry disease. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2019, 11, 1683–1696. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, W.; Chen, M.; Lv, X.; Lu, S.; Wang, C.; Yin, L.; Qian, L.; Shi, J. Status and frontiers of Fabry disease. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2025, 20, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombach, S.M.; Smid, B.E.; Linthorst, G.E.; Dijkgraaf, M.G.; Hollak, C.E. Natural course of Fabry disease and effectiveness of enzyme replacement therapy. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2014, 37, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garagiola, I.; Palla, R.; Peyvandi, F. Risk factors for inhibitor development in severe hemophilia A. Thromb. Res. 2018, 168, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, D.S.; Goldstein, J.L.; Banugaria, S.; Dai, J.; Mackey, J.; Rehder, C.; Kishnani, P.S. Predicting CRIM status in Pompe disease. Am. J. Med. Genet. C 2012, 160, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, W.R.; Linthorst, G.E.; Germain, D.P.; Feldt-Rasmussen, U.; Waldek, S.; Richards, S.M.; Beitner-Johnson, D.; Cizmarik, M.; Cole, J.A.; Kingma, W.; et al. Anti–α-galactosidase A antibody response to agalsidase beta: Fabry Registry data. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012, 105, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, M.; Ikeda, Y.; Otaka, H.; Iwashiro, S. Long-term safety of enzyme replacement therapy with agalsidase alfa in patients with Fabry disease: Post-marketing extension surveillance in Japan. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2024, 40, 101122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Cerezo, J.F.; Fernández-Martín, J.; Barba-Romero, M.Á.; Sánchez-Martínez, R.; Hermida-Ameijeiras, A.; Camprodon-Gómez, M.; Ortolano, S.; Lopez-Rodriguez, M.A. Immunogenicity of ERT in Fabry disease. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2025, 20, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keslová-Veselíková, J.; Hůlková, H.; Dobrovolný, R.; Asfaw, B.; Poupetová, H.; Berná, L.; Sikora, J.; Goláň, L.; Ledvinová, J.; Elleder, M. Replacement of α-galactosidase A in Fabry disease: Effect on fibroblasts and patient tissues. Virchows Arch. 2008, 452, 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, P.B. Fabry disease, enzyme replacement therapy and the significance of antibody responses. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2012, 35, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnock, D.G.; Wallace, E.L. Response to commentary: Head-to-head trial of pegunigalsidase alfa versus agalsidase beta in patients with Fabry disease and deteriorating renal function: Results from the 2-year randomised phase III BALANCE study—Determination of immunogenicity. J. Med. Genet. 2024, 61, 534–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linthorst, G.E.; Hollak, C.E.; Donker-Koopman, W.E.; Strijland, A.; Aerts, J.M. Enzyme therapy for Fabry disease: Neutralizing antibodies toward agalsidase alpha and beta. Kidney Int. 2004, 66, 1589–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bork, K.; Horstkorte, R.; Weidemann, W. Increasing the sialylation of therapeutic glycoproteins: The potential of the sialic acid biosynthetic pathway. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 98, 3499–3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, D.; Taylor, R.E.; Padler-Karavani, V.; Diaz, S.; Varki, A. Implications of the presence of N-glycolylneuraminic acid in recombinant therapeutic glycoproteins. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 863–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuraba, H.; Murata-Ohsawa, M.; Kawashima, I.; Tajima, Y.; Kotani, M.; Ohshima, T.; Chiba, Y.; Takashiba, M.; Jigami, Y.; Fukushige, T.; et al. Comparison of the effects of agalsidase alfa and agalsidase beta on cultured human Fabry fibroblasts and Fabry mice. J. Hum. Genet. 2006, 51, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekri, S. Importance of glycosylation in enzyme replacement therapy. In Fabry Disease: Perspectives from 5 Years of FOS; Mehta, A., Beck, M., Sunder-Plassmann, G., Eds.; Oxford PharmaGenesis: Oxford, UK, 2006; Chapter 5. [Google Scholar]

- Meghdari, M.; Gao, N.; Abdullahi, A.; Stokes, E.; Calhoun, D.H. Carboxyl-terminal truncations alter α-galactosidase A activity. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vedder, A.C.; Breunig, F.; Donker-Koopman, W.E.; Mills, K.; Young, E.; Winchester, B.; Berge, I.J.T.; Groener, J.E.; Aerts, J.M.; Wanner, C.; et al. Treatment of Fabry disease with different dosing regimens of agalsidase. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2008, 94, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedder, A.C.; Linthorst, G.E.; Houge, G.; Groener, J.E.; Ormel, E.E.; Bouma, B.J.; Aerts, J.M.; Hirth, A.; Hollak, C.E. Treatment of Fabry disease: Comparative trial of agalsidase alfa or beta at 0.2 mg/kg. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, G.M. Agalsidase alfa: A review of its use in Fabry disease. BioDrugs 2012, 26, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenders, M.; Menke, E.R.; Rudnicki, M.; Cybulla, M.; Brand, E. Neutralizing antibodies and pharmacokinetics of pegunigalsidase alfa. BioDrugs 2025, 39, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Kulkarni, Y.; Pierre, V.; Maski, M.; Wanner, C. Adverse impacts of PEGylated protein therapeutics. BioDrugs 2024, 38, 795–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenders, M.; Pollmann, S.; Terlinden, M.; Brand, E. Pre-existing antibodies in Fabry disease: Reduced affinity for pegunigalsidase alfa. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2022, 26, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shire Human Genetic. Replagal (Agalsidase Alfa); Shire Human Genetic: Cambridge, MA, USA; Belfast, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Barbey, F.; Livio, F. Safety of enzyme replacement therapy. In Fabry Disease: Perspectives from 5 Years of FOS; Oxford PharmaGenesis: Oxford, UK, 2006; Chapter 41. [Google Scholar]

- Genzyme Corporation. Fabrazyme (Agalsidase Beta); Genzyme Corporation: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, L.; Walter, J.; Johnson, J.; Alton, J.; Powers, J.; Llòria, X.; Koulinska, I.; McGee, M.; Laney, D. Patient-reported experience with Fabry disease. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2024, 19, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelman, F.D. Anaphylaxis: Lessons from mouse models. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007, 120, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matucci, A.; Vultaggio, A.; Nencini, F.; Maggi, E. Anaphylactic reactions to biological drugs. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 20, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenders, M.; Brand, E. Effects of ERT and antidrug antibodies in Fabry disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 29, 2265–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesenbach, P.; Kain, R.; Derfler, K.; Perkmann, T.; Soleiman, A.; Benharkou, A.; Druml, W.; Rees, A.; Säemann, M.D. Long-Term Outcome of Anti-Glomerular Basement Membrane Antibody Disease Treated with Immunoadsorption. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, T.; Iizuka, S.; Ida, H.; Eto, Y. Reduced α-Gal A enzyme activity in Fabry fibroblast cells and Fabry mice tissues induced by serum from antibody positive patients with Fabry disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2008, 94, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bénichou, B.; Goyal, S.; Sung, C.; Norfleet, A.M.; O’Brien, F. A retrospective analysis of the potential impact of IgG antibodies to agalsidase β on efficacy during enzyme replacement therapy for Fabry disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2009, 96, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Veen, S.J.; van Kuilenburg, A.B.P.; Hollak, C.E.M.; Kaijen, P.H.P.; Voorberg, J.; Langeveld, M. Antibodies against recombinant alpha-galactosidase A in Fabry disease: Subclass analysis and impact on response to treatment. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2019, 126, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, A.; Mechtler, T.P.; Desnick, R.J.; Kasper, D.C. Plasma LysoGb3 as a biomarker. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2017, 120, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharnetzki, D.; Stappers, F.; Lenders, M.; Brand, E. Epitope mapping of neutralizing antibodies in Fabry disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2020, 131, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronco, P.; Debiec, H. Advances in membranous nephropathy. Lancet 2015, 385, 1983–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombach, S.M.; Aerts, J.M.; Poorthuis, B.J.; Groener, J.E.; Donker-Koopman, W.; Hendriks, E.; Mirzaian, M.; Kuiper, S.; A Wijburg, F.; Hollak, C.E.M.; et al. Long-term effect of antibodies on lysoGb3 reduction. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenders, M.; Canaan-Kühl, S.; Krämer, J.; Duning, T.; Reiermann, S.; Sommer, C.; Stypmann, J.; Blaschke, D.; Üçeyler, N.; Hense, H.-W.; et al. Patients with Fabry Disease after Enzyme Replacement Therapy Dose Reduction and Switch–2-Year Follow-Up. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 952–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stappers, F.; Scharnetzki, D.; Schmitz, B.; Manikowski, D.; Brand, S.M.; Grobe, K.; Lenders, M.; Brand, E. Neutralising anti-drug antibodies in Fabry disease can inhibit endothelial enzyme uptake and activity. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2020, 43, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramaswami, U.; Bichet, D.G.; Clarke, L.A.; Dostalova, G.; Fainboim, A.; Fellgiebel, A.; Forcelini, C.M.; Haack, K.A.; Hopkin, R.J.; Mauer, M.; et al. Low-dose agalsidase beta in pediatric males. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2019, 127, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenders, M.; Stypmann, J.; Duning, T.; Schmitz, B.; Brand, S.M.; Brand, E. Serum-Mediated Inhibition of Enzyme Replacement Therapy in Fabry Disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenders, M.; Schmitz, B.; Brand, S.M.; Foell, D.; Brand, E. Drug-neutralizing antibodies during infusion. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 141, 2289–2292.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenders, M.; Neußer, L.P.; Rudnicki, M.; Nordbeck, P.; Canaan-Kühl, S.; Nowak, A.; Cybulla, M.; Schmitz, B.; Lukas, J.; Wanner, C.; et al. Dose-Dependent Effect of Enzyme Replacement Therapy on Neutralizing Antidrug Antibody Titers and Clinical Outcome in Patients with Fabry Disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 29, 2879–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenders, M.; Brand, E. Dose escalation and antidrug antibodies. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1024963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaridis, K.; Baltatzidou, V.; Tektonidis, N.; Tzartos, S.J. Antigen-specific immunoadsorption of MuSK autoantibodies as a treatment of MuSK-induced experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis. J. Neuroimmunol. 2020, 339, 577136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handisurya, A.; Worel, N.; Rabitsch, W.; Bojic, M.; Pajenda, S.; Reindl-Schwaighofer, R.; Winnicki, W.; Vychytil, A.; Knaus, H.A.; Oberbauer, R.; et al. Antigen-Specific Immunoadsorption With the Glycosorb® ABO Immunoadsorption System as a Novel Treatment Modality in Pure Red Cell Aplasia Following Major and Bidirectional ABO-Incompatible Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 585628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavenski, K.; Bucholz, M.; Cheatley, P.L.; Krok, E.; Anderson, M.; Prasad, G.R.; Qureshi, M.A.; Meliton, G.; Zaltzman, J. The First North American Experience Using Glycosorb Immunoadsorption Columns for Blood Group-Incompatible Kidney Transplantation. Can. J. Kidney Health Dis. 2020, 7, 2054358120962586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, P.; Harris, R.; Mitra, S. Chapter Four—Immunoadsorption techniques and its current role in the intensive care unit, aspects in continuous renal replacement therapy. In Aspects in Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy; Karkar, A., Ed.; IntechOpen: Londen, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenders, M.; Scharnetzki, D.; Heidari, A.; Di Iorio, D.; Wegner, S.V.; Brand, E. Generation and Characterization of a Polyclonal Human Reference Antibody to Measure Anti-Drug Antibody Titers in Patients with Fabry Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poelman, E.; Hoogeveen-Westerveld, M.; van den Hout, J.M.P.; Bredius, R.G.M.; Lankester, A.C.; Driessen, G.J.A.; Kamphuis, S.S.M.; Pijnappel, W.W.M.; van der Ploeg, A.T. Immunomodulation in infantile Pompe disease with high antibody titers. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2019, 14, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banugaria, S.G.; Prater, S.N.; Patel, T.T.; Dearmey, S.M.; Milleson, C.; Sheets, K.B.; Bali, D.S.; Rehder, C.W.; Raiman, J.A.J.; A Wang, R.; et al. Algorithm for the early diagnosis and treatment of patients with cross reactive immunologic material-negative classic infantile pompe disease: A step towards improving the efficacy of ERT. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allinovi, M.; Teisseyre, M.; Accinno, M.; Finocchi, C.; Esnault, V.L.M.; Cremoni, M.; Mazzierli, T.; Lazzarini, D.; Casiraghi, M.A.; Fernandez, C.; et al. Anti-rituximab antibodies in membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int. Rep. 2025, 10, 2621–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, P.; Peinovich, M.; McEntee, M.; Lester, T.; Le, S.; Krieger, A.; Manuel, H.; Jabagat, C.; Passage, M.; Kakkis, E.D. Immune tolerance improves the efficacy of enzyme replacement therapy in canine mucopolysaccharidosis I. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 2868–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.J.; Yi, J.S.; Lim, J.A.; Tedder, T.F.; Koeberl, D.D.; Jeck, W.; Desai, A.K.; Rosenberg, A.; Sun, B.; Kishnani, P.S. Successful AAV8 readministration: Suppression of capsid-specific neutralizing antibodies by a combination treatment of bortezomib and CD20 mAb in a mouse model of Pompe disease. J. Gene Med. 2023, 25, e3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.A.; Hsu, R.H.; Fang, C.Y.; Desai, A.K.; Lee, N.C.; Hwu, W.L.; Tsai, F.-J.; Kishnani, P.S.; Chien, Y.-H. Optimizing treatment outcomes: Immune tolerance induction in Pompe disease patients undergoing enzyme replacement therapy. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1336599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBuske, I.; Schmidlin, K.; Bernstein, J.A. Successful desensitization to agalsidase beta anaphylaxis with omalizumab. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021, 126, 96–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garman, R.D.; Munroe, K.; Richards, S.M. Methotrexate reduces antibody responses to recombinant human alpha-galactosidase A therapy in a mouse model of Fabry disease. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2004, 137, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenders, M.; Oder, D.; Nowak, A.; Canaan-Kühl, S.; Arash-Kaps, L.; Drechsler, C.; Schmitz, B.; Nordbeck, P.; Hennermann, J.B.; Kampmann, C.; et al. Impact of immunosuppressive therapy on therapy-neutralizing antibodies in transplanted patients with Fabry disease. J. Intern. Med. 2017, 282, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mignani, R.; Americo, C.; Aucella, F.; Battaglia, Y.; Cianci, V.; Sapuppo, A.; Lanzillo, C.; Pennacchiotti, F.; Tartaglia, L.; Marchi, G.; et al. Reduced infusion time of agalsidase beta: Low antibody formation. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2024, 19, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Agalsidase-α | Agalsidase-β | Pegunigalsidase-α | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of action | ERT from human embryonic cell line | ERT from CHO cells | ERT with pegylated enzyme from tobacco plant cells |

| Mode and frequency of administration | IV infusion, every 2 wks | IV infusion, every 2 wks | IV infusion, every 2 wks (4 wks in study) |

| Treated population | Wide, included null mutations | Wide, included null mutations | Wide, included null mutations |

| IRRs | IRRs are reported in 10% to 24% of pts * | 70% of pts present IRRs * | Limited IRRs are reported * |

| ADAs | ADAs are reported as ranging from 20% to 55% [19,20,21] ** | ADAs are reported as ranging from 73% to 91% [19,20,21] ** | 16% of pts develop ADAs |

| Production cell line and glycosylation patterns influence immunogenicity | Agalsidase-α derives from human fibroblasts, whereas agalsidase-β is produced from CHO cells and contains non-human sialic acids that can trigger immune responses. |

| Immunogenicity of the infused enzyme | RCTs and PMS indicate a higher incidence of ADAs in patients treated with agalsidase-β vs. agalsidase-α. |

| Cross-reactivity has implications for switching | IgG ADAs against one ERT can cross-react with the other, with implications for switching therapies or interpreting immunogenicity data. |

| Pegunigalsidase-α represents an option, but immunogenicity is not completely overcome | Pegunigalsidase-α offers potential benefit in pts with existing ADAs against ERTs; however, it still induces ADAs and pre-existing anti-PEG or anti-AGAL ADAs can reduce its activity through immune complex formation. |

| ADA-Mediated Inhibition | Neutralizing IgG1 and IgG4 ADAs block key epitopes on agalsidase, impairing M6P receptor uptake and reducing intracellular α-GAL activity. |

| Reduced Biomarker Clearance | High ADA titers correlate with persistent elevation of lysoGb3 and limited Gb3 clearance, especially in plasma and urine. |

| Altered Pharmacodynamics | ADAs form immune complexes that increase enzyme clearance via Fcγ receptor pathways, diminishing ERT efficacy. |

| Clinical Impact | ADA-positive patients, especially those with inhibitory ADAs, show worse clinical outcomes, accelerated renal decline, and increased disease severity. |

| Non-Neutralizing ADA Effects | Non-neutralizing ADAs may disrupt enzyme trafficking and conformation, affecting overall pharmacokinetics and therapeutic response. |

| IARs | ADA-positive patients are prone to develop IARs due to unclear pathogenic mechanisms. |

| Dose escalation | Dose escalation of ERT may help saturating ADA titers, but responses are variable, and this approach is likely effective in patients with low to moderate ADAs levels. |

| Antigen-specific IA | Antigen-specific IA can selectively deplete anti-AGAL antibodies in vitro. However, rapid ADA rebound would require frequent IA sessions, and its clinical application in FD remains investigational. |

| IS therapy | Early IS therapy may prevent ADA formation, as shown in Pompe and MPS-1. IS regimens include rituximab, methotrexate, IVIG, and bortezomib. |

| Minimizing immunogenicity from the start | Given the risks and long-term adverse effects of IS agents, it may be advisable to consider modifying the early therapeutic scheme to avoid the need for IS strategies later on. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Matucci, A.; Feriozzi, S.; Biagini, E.; Mangeri, M.; Accinno, M.; Diomiaiuti, M.; Ditaranto, R.; Chimenti, C.; Cirami, C.; Graziani, F.; et al. Immunogenicity in Fabry Disease: Current Issues, Coping Strategies, and Future Directions. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020343

Matucci A, Feriozzi S, Biagini E, Mangeri M, Accinno M, Diomiaiuti M, Ditaranto R, Chimenti C, Cirami C, Graziani F, et al. Immunogenicity in Fabry Disease: Current Issues, Coping Strategies, and Future Directions. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(2):343. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020343

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatucci, Andrea, Sandro Feriozzi, Elena Biagini, Mario Mangeri, Matteo Accinno, Michael Diomiaiuti, Raffaello Ditaranto, Cristina Chimenti, Calogero Cirami, Francesca Graziani, and et al. 2026. "Immunogenicity in Fabry Disease: Current Issues, Coping Strategies, and Future Directions" Biomedicines 14, no. 2: 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020343

APA StyleMatucci, A., Feriozzi, S., Biagini, E., Mangeri, M., Accinno, M., Diomiaiuti, M., Ditaranto, R., Chimenti, C., Cirami, C., Graziani, F., Pisani, A., & Vultaggio, A. (2026). Immunogenicity in Fabry Disease: Current Issues, Coping Strategies, and Future Directions. Biomedicines, 14(2), 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020343