Diagnostic Potential of Metabolomic and Proteomic Biomarkers in Cardiology—A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

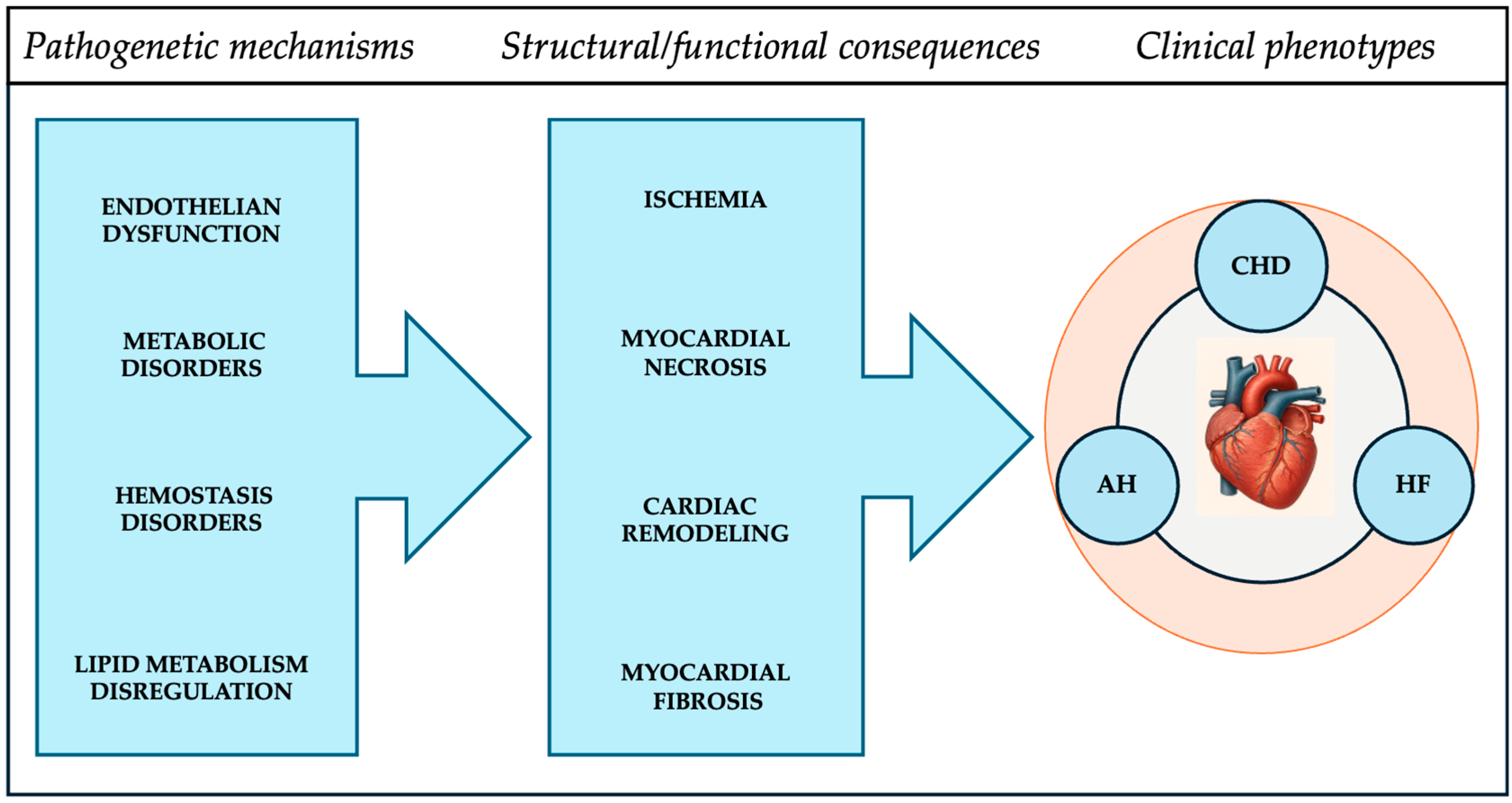

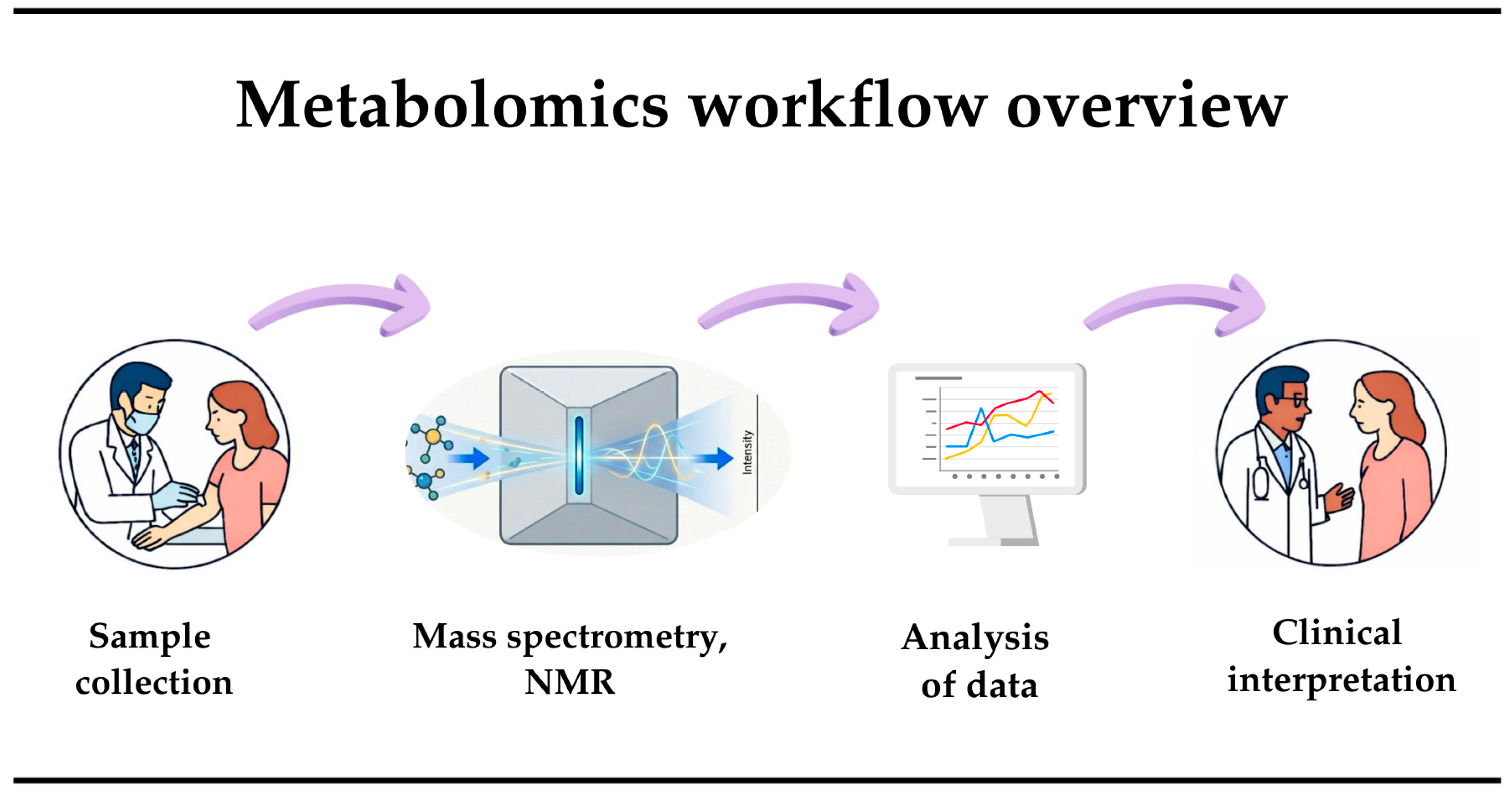

3.1. New Approaches in Cardiology

3.2. Markers of Neuroendocrine Activation and Left Ventricular Function

3.3. Inflammatory Markers

3.4. Hemostasis System Markers (Coagulation Factors)

3.5. Predictors of Lipid Metabolism Disorders

3.6. Myocardial Fibrosis Markers

3.7. Myocardial Necrosis Markers

3.8. Markers of Endothelial Dysfunction

3.9. Markers of Metabolic Disorders

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADMA | Asymmetric dimethylarginine |

| ADM | Adrenomedullin |

| AHA | American Heart Association |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| ANP | Atrial natriuretic peptide |

| Apo-B | Apolipoprotein B |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| BCAAs | Branched-chain amino acids |

| BCKAs | Branched-chain α-keto acids |

| BNP | Brain natriuretic peptide |

| CPK | Creatine phosphokinase |

| CHD | Coronary heart disease |

| CVD | Cardiovascular diseases |

| C2, C8, C14:1 | Acylcarnitines |

| Cer(d18:1/16:0) | Sphingolipids/Ceramides |

| ET-1 | Endothelin-1 |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 |

| FPA | Fibrinopeptide A |

| GDF-15 | Growth and differentiation factor |

| GC-MS | Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry |

| HDMB | Human Database of Metabolomics Biomarkers |

| HDL | High-density lipoprotein |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| hs-cTnT | High-sensitive troponin T |

| hs-cTnI | High-sensitive troponin I |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| MS | Mass spectrometry |

| MACE | Major Adverse Cardiac Events |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| LPC, PE, SM | Lipids/Phospholipids |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NT-proBNP | Natriuretic peptide |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| PICP | Type I procollagen propeptide |

| t-PA | Tissue plasminogen activator |

| RBP4 | Retinol-binding protein 4 |

| ST2 | Growth stimulation factor |

| TIMP-1 | Tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases 1 |

| TIMP-2 | Tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases 2 |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| sTM | Thrombomodulin |

| VCAM-1 | Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 |

| VWF | Von Willebrand factor |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| 12-HETE, 15-HETE | Oxylipins |

References

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- World Health Organization. Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases in Kazakhstan: The Case for Investment; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/WHO-EURO-2019-3643-43402-60941 (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- Statistical Compendium “Health of the Population of the Republic of Kazakhstan”. 2020. Available online: https://stat.gov.kz/ru/publication/collections/ (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- Sood, A.; Singh, A.; Gadkari, C. Myocardial Infarction in Young Individuals: A Review Article. Cureus 2023, 15, e37102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nurkina, D.; Zhussupbekova, L.; Baimuratova, M.; Janpaizov, T.; Akhmetov, Y. Prevalence of Cardiovascular Risk Factors Among Young Patients with Myocardial Infarction. J. Hypertens. 2025, 43, e247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhussupbekova, L.; Nurkina, D.; Sarkulova, S.; Smailova, G.; Zholamanov, K. Acute Forms of Coronary Artery Disease in the Nosological Structure of Hospitalization of Young People in Almaty City Cardiology Center. Georgian Med. News 2024, 355, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rootwelt, R.; Benedikte, K.; Elgstøen, P. Metabolomics—A New Biochemical Golden Age for Personalised Medicine. Tidsskr. Nor. Legeforening 2022, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, E.M.; Xu, L.Y. Guide to Metabolomics Analysis: A Bioinformatics Workflow. Metabolites 2022, 12, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abdullaev, A.; Abdullaeva, G.; Yusupova, K. Metabolomic Approaches in the Study of Cardiovascular Diseases. Eurasian Cardiol. J. 2021, 113, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. The National FINRISK Study. Available online: https://thl.fi/en/research-and-development/research-and-projects/the-national-finrisk-study (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- The Metabolomics Innovation Group. The Human Metabolome Database. Available online: https://www.hmdb.ca (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- Kale, D.; Fatangare, A.; Phapale, P.; Sickmann, A. Blood-Derived Lipid and Metabolite Biomarkers in Cardiovascular Research from Clinical Studies: A Recent Update. Cells 2023, 12, 2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Heinemann, J. Machine Learning in Untargeted Metabolomics Experiments. In Microbial Metabolomics; Baidoo, E., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, E.; Ibrahimi, E.; Ntalianis, E.; Cauwenberghs, N.; Kuznetsova, T. Integrating Metabolomics Domain Knowledge with Explainable Machine Learning in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Classification. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Cai, M.; Kang, Y.; Liu, J. Progress in Biomarkers and Diagnostic Approaches for Myocardial Infarction. Clin. Chim. Acta 2026, 579, 120629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuitema, P.C.E.; Visseren, F.L.J.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Teraa, M.; van der Meer, M.G.; Ruigrok, Y.M.; Onland-Moret, N.C.; Koopal, C.; UCC-SMART Study Group. Elevated triglycerides are related to higher residual cardiovascular disease and mortality risk independent of lipid targets and intensity of lipid-lowering therapy in patients with established cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis 2025, 408, 120411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatia, H.S.; Wandel, S.; Willeit, P.; Lesogor, A.; Bailey, K.; Ridker, P.M.; Nestel, P.; Simes, J.; Tonkin, A.; Schwartz, G.G.; et al. Independence of Lipoprotein(a) and Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol-Mediated Cardiovascular Risk: A Participant-Level Meta-Analysis. Circulation 2025, 151, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Singh, S.; Baars, D.P.; Aggarwal, K.; Desai, R.; Singh, D.; Pinto-Sietsma, S.J. Association between lipoprotein (a) and risk of heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of Mendelian randomization studies. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2024, 49, 102439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fine, K.S.; Wilkins, J.T.; Sawicki, K.T. Circulating Branched Chain Amino Acids and Cardiometabolic Disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e031617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Peng, Y.; Duan, Y.; Wang, D.; Liu, J.; Zhao, G.; Ji, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wei, B. BCAA Exaggerated Acute and Chronic Ischemic Heart Disease Through Promotion of NLRP3 Via Sirt1. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2025, 241, 117150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanase, D.M.; Valasciuc, E.; Costea, C.F.; Scripcariu, D.V.; Ouatu, A.; Hurjui, L.L.; Tarniceriu, C.C.; Floria, D.E.; Ciocoiu, M.; Baroi, L.G.; et al. Duality of Branched-Chain Amino Acids in Chronic Cardiovascular Disease: Potential Biomarkers versus Active Pathophysiological Promoters. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwed, A.; Kim, E.; Jacinto, E. Regulation and Metabolic Functions of mTORC1 and mTORC2. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 1371–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gander, J.; Carrard, J.; Gallart-Ayala, H.; Borreggine, R.; Teav, T.; Infanger, D.; Colledge, F.; Streese, L.; Wagner, J.; Klenk, C.; et al. Metabolic Impairment in Coronary Artery Disease: Elevated Serum Acylcarnitines Under the Spotlights. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 792350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rizo-Roca, D.; Henderson, J.D.; Zierath, J.R. Metabolomics in Cardiometabolic Diseases: Key Biomarkers and Therapeutic Implications for Insulin Resistance and Diabetes. J. Intern. Med. 2025, 297, 584–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Datta, S.; Koka, S.; Boini, K.M. Understanding the Role of Adipokines in Cardiometabolic Dysfunction: A Review of Current Knowledge. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astafieva, O.; Zharkova, A.; Yasenevskaya, A.; Nikitina, I.; Goretova, I.; Fedoseev, I.; Bashkina, O.; Samotrueva, M. Review of Metabolomic Markers Used for the Diagnosis of Cardiovascular Diseases. Sib. Sci. Med. J. 2022, 42, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwardeen, N.; Naja, K.; Elrayess, M. Association Between Antioxidant Metabolites and N-Terminal Fragment Brain Natriuretic Peptides in Insulin-Resistant Individuals. Cardiovasc. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 13, e0303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.B.; Zhang, S.; McEvoy, J.; Ndumele, C.; Hoogeveen, R.; Coresh, J.; Selvin, E. Elevated NT-Probnp as an Equivalent of Cardiovascular Disease Risk: Data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am. J. Med. 2022, 135, 1461–1467, Erratum in Am. J. Med. 2023, 136, 329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2022.11.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Choy, K.W.; Wijeratne, N.; Chiang, C.; Don-Wauchope, A. Copeptin as a surrogate marker for arginine vasopressin: Analytical insights, current utility, and emerging applications. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2025, 62, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, L.; Chisalita, S.; Gauffin, E.; Engvall, J.; Östgren, C.; Nyström, F. Plasma Copeptin Independently Predicts Cardiovascular Events but Not All-Cause Mortality in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Prospective Observational Study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2025, 35, 104158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elseidy, S.; Awad, A.; Mandal, D.; Vorla, M.; Elkheshen, A.; Mohamad, T. Copeptin Plus Troponin in the Rapid Rule Out of Acute Myocardial Infarction and Prognostic Value on Post-Myocardial Infarction Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Diagnostic Accuracy Study. Heart Vessel. 2023, 38, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roczek-Janowska, M.; Kacprzak, M.; Dzieciol, M.; Zielinska, M.; Chizynski, K. Prognostic Value of Copeptin in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction Treated with Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Thorac. Dis. 2021, 13, 4094–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van Vugt, M.; Finan, C.; Chopade, S.; Providencia, R.; Bezzina, C.R.; Asselbergs, F.W.; van Setten, J.; Schmidt, A.F. Integrating metabolomics and proteomics to identify novel drug targets for heart failure and atrial fibrillation. Genome Med. 2024, 16, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voors, A.; Kremer, D.; Geven, C.; Ter Maaten, J.; Struck, J.; Bergmann, A.; Pickkers, P.; Metra, M.; Mebazaa, A.; Düngen, H.D.; et al. Adrenomedullin in heart failure: Pathophysiology and therapeutic application. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Müller, M.L.; Knebel, F.; Hahn, K.; Schulte, J.; Arlt, B.; Hartmann, O.; Moore, K.M.S.; Takashio, S.; Izumiya, Y.; Mitchell, J.D.; et al. Bio-Adrenomedullin Predicts Death and Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Cardiac Amyloidosis: A Cross-Continental Multicenter Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2026, 15, e043736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiffrin, E.; Pollock, D. Endothelin System in Hypertension and Chronic Kidney Disease. Hypertension 2024, 81, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gottlieb, S.S.; Harris, K.; Todd, J.; Estis, J.; Christenson, R.; Torres, V.; Whittaker, K.; Rebuck, H.; Wawrzyniak, A.; Krantz, D. Prognostic Significance of Active and Modified Forms of Endothelin 1 In Patients with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction. Clin. Biochem. 2015, 48, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebkar, A.; Kotani, K.; Serban, C.; Ursoniu, S.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Jones, S.R.; Ray, K.K.; Blaha, M.J.; Rysz, J.; Toth, P.P.; et al. Statin Therapy Reduces Plasma Endothelin-1 Concentrations: A Meta-Analysis of 15 Randomized Controlled Trials. Atherosclerosis 2015, 241, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhu, C.G.; Guo, Y.L.; Wu, N.Q.; Dong, Q.; Xu, R.X.; Wu, Y.J.; Qian, J.; Li, J.J. Prognostic Value of Plasma Endothelin-1 in Predicting Worse Outcomes in Patients with Prediabetes and Diabetes and Stable Coronary Artery Diseases. Diabetes Metab. J. 2024, 48, 993–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Qu, Q.; Lv, J. Serum Nitric Oxide, Endothelin-1 Correlates Post-Procedural Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events among Patients with Acute STEMI. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2025, 122, e20240248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Dhillon, O.; Struck, J.; Quinn, P.; Morgenthaler, N.G.; Squire, I.; Davies, J.; Bergmann, A.; Ng, L. C-Terminal Pro-Endothelin-1 Offers Additional Prognostic Information in Patients After Acute Myocardial Infarction: Leicester Acute Myocardial Infarction Peptide (LAMP) Study. Am Heart J. 2007, 154, 736–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moissl, A.P.; Delgado, G.E.; Scharnagl, H.; Siekmeier, R.; Krämer, B.K.; Duerschmied, D.; März, W.; Kleber, M.E. Comparing Inflammatory Biomarkers in Cardiovascular Disease: Insights from the LURIC Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.H.; Leong, X.B.; Mohamed, M. Systematic Review of Advanced Inflammatory Markers as Predictors of Cardiovascular Diseases. Res. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 14, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jang, Y. Inflammation in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Diseases: Biomarkers to Therapeutics in Clinical Settings. J. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2024, 3, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrot, N.; Verbeek, R.; Sandhu, M.; Boekholdt, S.M.; Hovingh, G.K.; Wareham, N.J.; Khaw, K.T.; Arsenault, B.J. Ideal cardiovascular health influences cardiovascular disease risk associated with high lipoprotein(a) levels and genotype: The EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study. Atherosclerosis 2017, 256, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, S.; Jiang, H.; Dhuromsingh, M.; Dai, L.; Jiang, Y.; Zeng, H. Evaluation of C-reactive protein as predictor of adverse prognosis in acute myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis from 18,715 individuals. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 1013501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mantovani, A.; Cassatella, M.A.; Costantini, C.; Jaillon, S. Humoral Innate Immunity and Acute-Phase Proteins. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 434–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geovanini, G.R.; Libby, P. Atherosclerosis and inflammation: Overview and updates. Clin. Sci. 2018, 132, 1243–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, W.; Khuseyinova, N. Biomarkers of Atherosclerotic Plaque Instability and Their Clinical Implications. Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovasc. Med. 2007, 4, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donoghue, M.L.; Morrow, M.; Cannon, D.; Jarolim, C.; Desai, P.; Sherwood, N.; Murphy, M.; Gerszten, S.; Sabatine, R. Multimarker Risk Stratification in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e002586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, Y.; Raines, E.W.; Plump, A.S.; Breslow, J.L.; Ross, R. Upregulation of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 at Atherosclerosis-Prone Sites on the Endothelium in the apoe-Deficient Mouse. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1998, 18, 842–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Liu, Y.; Peng, W.; Xu, Z. Serum VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 measurement assists for MACE risk estimation in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Urschel, K.; Cicha, I. TNF-α in the cardiovascular system: From physiology to therapy. Int. J. Interferon Cytokine Mediat. Res. 2015, 7, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, J.K.; Hotamisligil, G.S. Metabolic Messengers: Tumour necrosis factor. Nat Metab 2021, 3, 1302–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medentseva, O.; Udovychenko, M.; Rudyk, I.; Gasanov, I.; Babichev, D.; Galchinskaya, V. Association of Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha and Lipid Parameters in Patients with Coronary Heart Disease and Heart Failure. Atherosclerosis 2020, 315, e226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, Q.; Nadeem, T.; Youn, S.W.; Swaminathan, B.; Gupta, A.; Sargis, T.; Du, J.; Cuervo, H.; Eichmann, A.; Ackerman, S.L.; et al. Notch signaling regulates UNC5B to suppress endothelial proliferation, migration, junction activity, and retinal plexus branching. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martos-Rodríguez, C.J.; Albarrán-Juárez, J.; Morales-Cano, D.; Caballero, A.; MacGrogan, D.; de la Pompa, J.L.; Carramolino, L.; Bentzon, J.F. Fibrous Caps in Atherosclerosis Form by Notch-Dependent Mechanisms Common to Arterial Media Development. Atheroscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, e427–e439, Erratum in Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2022, 42, e85. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATV.0000000000000150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aquila, G.; Pannella, M.; Morelli, M.; Caliceti, C.; Fortini, C.; Rizzo, P.; Ferrari, R. The Role of Notch Pathway in Cardiovascular Diseases. Glob. Cardiol. Sci. Pract. 2013, 2013, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kwon, S.M.; Alev, C.; Asahara, T. The Role of Notch Signaling in Endothelial Progenitor Cell Biology. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2009, 19, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.J.; Tas, S.W.; de Winther, M.P.J. Type-I Interferons in Atherosclerosis. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20190459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elyasi, A.; Voloshyna, I.; Ahmed, S.; Kasselman, L.; Behbodikhah, J.; De Leon, J.; Reiss, A. The Role of Interferon-Γ in Cardiovascular Disease: An Update. Inflamm. Res. 2020, 69, 975–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Duan, L.; Cai, Y.L.; Li, H.Y.; Hao, B.C.; Chen, J.Q.; Liu, H.B. Growth Differentiation Factor-15 Is Associated with Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020, 19, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gridley, T. Notch Signaling in the Vasculature. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2010, 92, 277–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Białecka, M.; Dziedziejko, V.; Safranow, K.; Krzystolik, A.; Marcinowska, Z.; Chlubek, D.; Rać, M. Could Tumor Necrosis Factor Serve as a Marker for Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Left Ventricular Hypertrophy in Patients with Early-Onset Coronary Artery Disease? Diagnostics 2024, 14, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maisel, A.; Mueller, C.; Nowak, R.; Peacock, W.F.; Landsberg, J.W.; Ponikowski, P.; Mockel, M.; Hogan, C.; Wu, A.H.B.; Richards, M.; et al. Midregion Prohormone Markers for Diagnosis and Prognosis in Acute Dyspnea: Results from the BACH (Biomarkers in Acute Heart Failure) trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 56, 341–350. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, C.P.; Januzzi, J.L., Jr. Soluble ST2 in Heart Failure. Heart Fail. Clin. 2018, 14, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Roh, H.; Kwon, Y. Causes of Hyperhomocysteinemia and Its Pathological Significance. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2018, 41, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeoye, M.; Hamdallah, H.; Adeoye, A.M. Homocysteine levels and cardiovascular disease risk factors in chronic kidney disease (CKD), hypertensive and healthy Nigerian adults: A comparative retrospective study. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e089644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Karger, A.B.; Nomura, S.O.; Guan, W.; Garg, P.K.; Tison, G.H.; Szklo, M.; Budoff, M.J.; Tsai, M.Y. Association Between Elevated Total Homocysteine and Heart Failure Risk in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis Cohort. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, e038168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marroncini, G.; Martinelli, S.; Menchetti, S.; Bombardiere, F.; Martelli, F.S. Hyperhomocysteinemia and Disease—Is 10 μmol/L a Suitable New Threshold Limit? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manysheva, K.B.; Abusueva, B.A.; Umakhanova, Z.R. Role of mutations in MTHFR gene and hyperhomocysteinemia in occurrence of ischemic stroke. Med. Alph. 2021, 36, 41–46. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okura, T.; Miyoshi, K.; Irita, J.; Enomoto, D.; Nagao, T.; Kukida, M.; Tanino, A.; Kudo, K.; Pei, Z.; Higaki, J. Hyperhomocysteinemia is one of the risk factors associated with cerebrovascular stiffness in patients with hypertension, especially elderly men. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karadeniz, M.; Sarak, T.; Duran, M.; Alp, C.; Kandemir, H.; Etem, C.; Simsek, V.; Kılıc, A. Hyperhomocysteinemia Predicts the Severity of Coronary Artery Disease as Determined by the SYNTAX Score in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome. Acta Cardiol. Sin. 2018, 34, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Unadkat, S.V.; Padhi, B.K.; Bhongir, A.V.; Gandhi, A.P.; Shamim, M.A.; Dahiya, N.; Satapathy, P.; Rustagi, S.; Khatib, M.N.; Gaidhane, A.; et al. Association between homocysteine and coronary artery disease—Trend over time and across the regions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Egypt. Heart J. 2024, 76, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yong-Yi, B.; Luo, L.M.; Xiao, W.K.; Wu, H.M.; Ye, P. Association Between Serum Homocysteine and Arterial Stiffness in Older Adults: A Community-Based Study. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2014, 11, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; He, Y.; Xie, X.; Guo, N.; Chen, W.; Zhao, Y. Homocysteine and Multiple Health Outcomes: An Outcome-Wide Umbrella Review of Meta-analyses and Mendelian Randomization Studies. Adv. Nutr. 2025, 16, 100434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wolberg, A.S. Primed to Understand Fibrinogen in Cardiovascular Disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2016, 36, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tousoulis, D.; Papageorgiou, N.; Androulakis, E.; Briasoulis, A.; Antoniades, C.; Stefanadis, C. Fibrinogen and Cardiovascular Disease: Genetics and Biomarkers. Blood Rev. 2011, 25, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surma, S.; Banach, M. Fibrinogen and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Diseases-Review of the Literature and Clinical Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 23, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thompson, S.; Kienast, J.; Pyke, S.; Haverkate, F.; van de Loo, J.C. Hemostatic Factors and Risk of Myocardial Infarction or Sudden Death in Patients with Angina Pectoris. European Cooperative Study Group on Thrombosis and Disability in Angina. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995, 332, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacchiarini, L.; Storti, S.; Zucchella, M.; Salerno, J.; Grignani, G.; Fratino, P. Fibrinopeptide A Levels in Patients with Acute Ischaemic Heart Disease. Pathophysiol. Haemost. Thromb. 1989, 19, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, H.; Maeno, T.; Fukumoto, S.; Shoji, T.; Yamane, T.; Yokoyama, H.; Emoto, M.; Tahara, H.; Inaba, M.; Hino, M.; et al. Platelet P-selectin expression is associated with atherosclerotic wall thickness in carotid artery in humans. Circulation 2003, 108, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoddam, A.; Vaughan, D.; Wilsbacher, L. Role of Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) In Age-Related Cardiovascular Pathophysiology. J. Cardiovasc. Aging. 2025, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.; Balaya, R.D.A.; Dagamajalu, S.; Bhandary, Y.; Unwalla, H.; Prasad, T.; Rahman, I. A Signaling Pathway Map of Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 (PAI-1/SERPINE-1): A Review of an Innovative Frontier in Molecular Aging and Cellular Senescence. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schneider, M.F.; Fallah, M.A.; Mess, C.; Obser, T.; Schneppenheim, R.; Alexander-Katz, A.; Schneider, S.W.; Huck, V. Platelet Adhesion and Aggregate Formation Controlled by Immobilised and Soluble VWF. BMC Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankovic, S.; Radisavljevic, N.M.; Bajic, Z.; Polovina, M.; Djuric, D.M. Circulating Biomarkers in the Detection of Cardiovascular Toxicity. In Cardiovascular Toxicity; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 621–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministrini, S.; Tirandi, A. Von Willebrand factor in inflammation and heart failure: Beyond thromboembolic and bleeding risk. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3868–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Paridon, P.C.S.; Panova-Noeva, M.; van Oerle, R.; Schulz, A.; Prochaska, J.H.; Arnold, N.; Schmidtmann, I.; Beutel, M.; Pfeiffer, N.; Münzel, T.; et al. Lower levels of vWF are associated with lower risk of cardiovascular disease. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2022, 6, e12797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Wang, X.; Peng, X.; Feng, S.; Zhao, J.; Liao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Liu, J. Prognostic value of plasma von Willebrand factor levels in major adverse cardiovascular events: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2020, 20, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, F.A.; Murphy, R.P.; Cummins, P.M. Thrombomodulin and the vascular endothelium: Insights into functional, regulatory, and therapeutic aspects. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2013, 304, H1585–H1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Van de Wouwer, M.; Collen, D.; Conway, E.M. Thrombomodulin-protein C-EPCR system: Integrated to regulate coagulation and inflammation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004, 24, 1374–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, K. Thrombomodulin: A Key Regulator of Intravascular Blood Coagulation, Fibrinolysis, and Inflammation, as Well as Treatment of Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2025, 101, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lin, S.M.; Chang, C.H.; Lin, T.Y.; Huang, A.C.C.; Lin, C.H.; Chen, Y.C.; Chu, P.H. Plasma Thrombomodulin Levels Are Associated with Acute Kidney Injury in Patients with Acute Heart Failure. Ann. Med. 2022, 54, 3168–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misirlioglu, N.F.; Orucoglu, G.G.; Bıcakhan, B.; Kucuk, S.H.; Himmetoglu, S.; Sayili, S.B.; Ozen, G.D.; Uzun, H. Evaluation of Thrombomodulin, Heart-Type Fatty-Acid-Binding Protein, Pentraxin-3 and Galectin-3 Levels in Patients with Myocardial Infarction, with and Without ST Segment Elevation. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmon, C.T.; Owen, W.G. The Discovery of Thrombomodulin. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2004, 2, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baysal, S.S. Evaluation of the Relationship Between Resting Heart Rate and Endocan, Thrombomodulin Levels in Healthy Adults. J. Updates Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 7, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, C.J.; Elosua, R. Factores De Riesgo Cardiovascular. Perspectivas Derivadas del Framingham Heart Study [Cardiovascular risk factors. Insights from Framingham Heart Study]. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2008, 61, 299–310. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, S.; Hawken, S.; Ounpuu, S.; Dans, T.; Avezum, A.; Lanas, F.; McQueen, M.; Budaj, A.; Pais, P.; Varigos, J.; et al. Effect of Potentially Modifiable Risk Factors Associated with Myocardial Infarction in 52 Countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-Control Study. Lancet 2004, 364, 937–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorster, A.; Kruger, R.; Mels, C.M.; Breet, Y. Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors are Associated with Conventional Lipids and Apolipoproteins in South African Adults of African Ancestry. Lipids Health Dis. 2025, 24, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wan, H.; Wu, H.; Wei, Y.; Wang, S.; Ji, Y. Novel Lipid Profiles and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk: Insights from a Latent Profile Analysis. Lipids Health Dis. 2025, 24, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ji, Y.; Song, J.; Su, T.; Gu, X. Adipokine Retinol Binding Protein 4 and Cardiovascular Diseases. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 856298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fan, J.; Hu, J. Retinol Binding Protein 4 And Type 2 Diabetes: From Insulin Resistance to Pancreatic Β-Cell Function. Endocrine 2024, 85, 1020–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, T.E.; Yang, Q.; Blüher, M.; Hammarstedt, A.; Ciaraldi, T.P.; Henry, R.R.; Wason, C.J.; Oberbach, A.; Jansson, P.A.; Smith, U.; et al. Retinol-Binding Protein 4 And Insulin Resistance in Lean, Obese, And Diabetic Subjects. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 2552–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; Kiernan, U.A.; Shi, L.; Phillips, D.A.; Kahn, B.B.; Hu, F.B.; Manson, J.E.; Albert, C.M.; Rexrode, K.M. Plasma Retinol-Binding Protein 4 (RBP4) Levels and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease: A Prospective Analysis Among Women in the Nurses’ Health Study. Circulation 2013, 127, 1938–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Poetsch, M.S.; Strano, A.; Guan, K. Role of Leptin in Cardiovascular Diseases. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wallace, A.M. Measurement of Leptin and Leptin Binding in the Human Circulation. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2000, 37, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, S.S.; Qasim, A.; Reilly, M.P. Leptin Resistance: A Possible Interface of Inflammation and Metabolism in Obesity-Related Cardiovascular Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008, 52, 1201–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hansen, N.; Eriksson, M.A.; Andersson, J.S.O.; Soderberg, S. Leptin and adiponectin independently predict a first-ever myocardial infarction with a sex difference. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, ehaf784.1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanda, V.; Bracale, U.M.; Di Taranto, M.D.; Fortunato, G. Galectin-3 in Cardiovascular Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zaborska, B.; Sikora-Frąc, M.; Smarż, K.; Pilichowska-Paszkiet, E.; Budaj, A.; Sitkiewicz, D.; Sygitowicz, G. The Role of Galectin-3 in Heart Failure-The Diagnostic, Prognostic and Therapeutic Potential-Where Do We Stand? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sherpa, M.D.; Sonkawade, S.D.; Jonnala, V.; Pokharel, S.; Khazaeli, M.; Yatsynovich, Y.; Kalot, M.A.; Weil, B.R.; Canty, J.M., Jr.; Sharma, U.C. Galectin-3 Is Associated with Cardiac Fibrosis and an Increased Risk of Sudden Death. Cells 2023, 12, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Papazafiropoulou, A.; Tentolouris, N. Matrix Metalloproteinases And Cardiovascular Diseases. Hippokratia 2009, 13, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shumakov, D.V.; Zybin, D.I.; Popov, M.A. The Role of Matrix Metalloproteinase 9 in Left Ventricular Myocardial Remodeling. Res. Med. J. 2020, 10, 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Xue, Q.; Zhu, R.; Jiang, Y. Diagnostic Value of PICP and PIIINP in Myocardial Fibrosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Cardiol. 2022. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrieta, V.; Jover, E.; Navarro, A.; Martín-Núñez, E.; Garaikoetxea, M.; Matilla, L.; García-Peña, A.; Fernández-Celis, A.; Gainza, A.; Álvarez, V.; et al. Soluble ST2 Levels Are Related to Replacement Myocardial Fibrosis in Severe Aortic Stenosis. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2023, 76, 679–689. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.Y.; Heckbert, S.R.; Lai, S.; Ambale-Venkatesh, B.; Ostovaneh, M.R.; McClelland, R.L.; Lima, J.A.C.; Bluemke, D.A. Association of Elevated NT-proBNP With Myocardial Fibrosis in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 3102–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Du, L.; Wang, X.; Guo, Y.; Tao, T.; Wu, H.; Xu, X.; Zhang, B.; Chen, T.; Xu, Q.; Guo, X. Altered lipid metabolism promoting cardiac fibrosis is mediated by CD34+ cell-derived FABP4+ fibroblasts. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 1869–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackner, K.J. Cardiac Troponins—A Paradigm for Diagnostic Biomarker Identification and Development. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. (CCLM) 2023, 61, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksova, A.; Fluca, A.L.; Beltrami, A.P.; Dozio, E.; Sinagra, G.; Marketou, M.; Janjusevic, M. Biomarkers of Importance in Monitoring Heart Condition After Acute Myocardial Infarction. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, R.; Damarlapally, N.; Bareja, S.; Arote, V.; SuryaVasudevan, S.; Mehta, K.; Ashfaque, M.; Jayachandran, Y.; Sampath, S.; Behera, A.; et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Evaluating the Association of High Sensitivity Troponin Levels with Outcomes in Patients with Stable Coronary Artery Disease. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2024, 40, 1685–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, F.; Zervou, S.; Lygate, C.A. The Creatine Kinase System as a Therapeutic Target for Myocardial Ischaemia-Reperfusion Injury. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2018, 46, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sun, T.; Dong, Y.H.; Du, W.; Shi, C.Y.; Wang, K.; Tariq, M.A.; Wang, J.X.; Li, P.F. The Role of MicroRNAs in Myocardial Infarction: From Molecular Mechanism to Clinical Application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Jin, T.; Song, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, X.F.; Zeng, Y. Cer(d18:1/16:0) as a biomarkers for acute coronary syndrome in Chinese populations. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, S.A.; Alghamdi, M.; Alfaifi, J.; Alamri, M.M.S.; Al-Shahrani, A.M.; Alharthi, M.H.; Alshahrani, A.M.; Alhalafi, A.H.; Adam, M.I.E.; Bahashwan, E.; et al. The Emerging Role of Mirnas in Myocardial Infarction: From Molecular Signatures to Therapeutic Targets. Pathol.—Res. Pract. 2024, 253, 155087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endemann, D.H.; Schiffrin, E.L. Endothelial dysfunction. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2004, 15, 1983–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cyr, A.R.; Huckaby, L.V.; Shiva, S.S.; Zuckerbraun, B.S. Nitric Oxide and Endothelial Dysfunction. Crit. Care Clin. 2020, 36, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Timofeev, Y.S.; Mikhailova, M.A.; Dzhioeva, O.N.; Drapkina, O.M. Importance of Biological Markers in the Assessment Ofendothelial Dysfunction. Cardiovasc. Ther. Prev. 2024, 23, 4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naya, M.; Aikawa, T.; Manabe, O.; Obara, M.; Koyanagawa, K.; Katoh, C.; Tamaki, N. Elevated Serum Endothelin-1is an Independent Predictor of Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction in Non-Obstructive Territories in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. Heart Vessel. 2021, 36, 917–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visek, J.; Bláha, M.; Lánská, M.; Bláha, V.; Lasticova, M.; Doleželová, E.; Nachtigal, P. Soluble Endoglin in Patients with Homo/Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia Treated with Lipidapheresis. Atherosclerosis 2019, 287, E265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, R.; Paskin-Flerlage, S.; Zamanian, R.T.; Zimmerman, P.; Schmidt, J.W.; Deng, D.Y.; Southwood, M.; Spencer, R.; Lai, C.S.; Parker, W.; et al. Circulating Angiogenic Modulatory Factors Predict Survival and Functional Class in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Pulm. Circ. 2013, 3, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathouska, J.U.; Mrazkova, J.; Andrys, C.; Jankovicova, K.; Tripska, K.; Fikrova, P.; Nemeckova, I.; Eissazadeh, S.; Wohlfahrt, P.; Pitha, J.; et al. Soluble endoglin reflects endothelial dysfunction in myocardial infarction patients: A retrospective observational study. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2025, 22, 3220–3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, N.; Worthmann, H.; Deb, M.; Chen, S.; Weissenborn, K. Nitric Oxide (NO) And Asymmetric Dimethylarginine (ADMA): Their Pathophysiological Role and Involvement in Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Neurol. Res. 2011, 33, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janes, F.; Cifù, A.; Pessa, M.E.; Domenis, R.; Gigli, G.L.; Sanvilli, N.; Nilo, A.; Garbo, R.; Curcio, F.; Giacomello, R.; et al. ADMA as a Possible Marker of Endothelial Damage. A Study in Young Asymptomatic Patients with Cerebral Small Vessel Disease. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowsett, L.; Higgins, E.; Alanazi, S.; Alshuwayer, N.A.; Leiper, F.C.; Leiper, J. ADMA: A Key Player in the Relationship between Vascular Dysfunction and Inflammation in Atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Sharma, D.; Bisen, S.; Mukhopadhyay, C.S.; Gurdziel, K.; Singh, N.K. Vascular Cell-Adhesion Molecule 1 (VCAM-1) Regulates Junb-Mediated IL-8/CXCL1 Expression and Pathological Neovascularization. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haydinger, C.D.; Ashander, L.M.; Tan, A.C.R.; Smith, J.R. Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1: More than a Leukocyte Adhesion Molecule. Biology 2023, 12, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kong, D.-H.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, M.R.; Jang, J.H.; Lee, S. Emerging Roles of Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 (VCAM-1) in Immunological Disorders and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galkina, E.; Ley, K. Vascular adhesion molecules in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007, 27, 2292–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lino, D.O.; Freitas, I.A.; Meneses, G.K.; Martins, A.M.; Daher, E.F.; Rocha, J.H.; Silva, G.B. Interleukin-6 And Adhesion Molecules VCAM-1 And ICAM-1 As Biomarkers of Heart Failure After Acute Myocardial Infarction. Braz. J. Med. Biol. 2019, 52, e8658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markin, S.S.; Ponomarenko, E.A.; Romashova, Y.A.; Pleshakova, T.O.; Ivanov, S.V.; Bedretdinov, F.N.; Konstantinov, S.L.; Nizov, A.A.; Koledinskii, A.G.; Girivenko, A.I.; et al. A Novel Preliminary Metabolomic Panel for IHD Diagnostics and Pathogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Yan, W.; Gao, E.; Cheng, H.; Wu, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; et al. Branched Chain Amino Acids Exacerbate Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Vulnerability Via Enhancing GCN2/ATF6/PPAR-A Pathway-Dependent Fatty Acid Oxidation. Theranostics 2020, 10, 5623–5640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shah, S.H.; Sun, J.L.; Stevens, R.D.; Bain, J.R.; Muehlbauer, M.J.; Pieper, K.S.; Haynes, C.; Hauser, E.R.; Kraus, W.E.; Granger, C.B.; et al. Baseline metabolomic profiles predict cardiovascular events in patients at risk for coronary artery disease. Am. Heart J. 2012, 163, 844–850.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://eatlas.escardio.org/Data/Cardiovascular-disease-morbidity/hs_daly_cvd_std_100k_t_r-dalys-due-to-cvd-both (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- Nurkina, D.; Baimuratova, M.; Zhussupbekova, L.; Kodaspayev, A.; Alimbayeva, S. Assessment of risk factors of myocardial infarction in young persons. Georgian Med. News 2023, 334, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fine, K.S.; Wilkins, J.T.; Sawicki, K.T. Clinical Metabolomic Landscape of Cardiovascular Physiology and Disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e027725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group of Metabolites | Examples | Pathophysiological Role | Pathways | Type of MS | Number of Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino acids (BCAAs) | Leucine, Isoleucine, Valine | Insulin resistance, mTOR, remodeling | Protein metabolism, NO pathway | LC-MS/MS | ≈450 |

| Acylcarnitines (Acs) | C2, C8, C14:1 | Mitochondrial dysfunction | β-oxidation | LC-MS/MS | ≈320 |

| Lipids/Phospholipids | LPC, PE, SM | Atherogenesis, inflammation | Lipid metabolism | LC-MS/MS | ≈700 |

| Sphingolipids/Ceramides | Cer(d18:1/16:0) | MACE risk, endothelium | Sphingosine pathway | LC-MS/MS | ≈280 |

| Oxylipins | 12-HETE, 15-HETE | Inflammation, thrombosis | LOX/COX | LC-MS/MS | ≈260 |

| Amino acid derivatives | TMAO, ADMA, SDMA | NO-dysfunction, microbiome | Arginine-NO pathway | LC-MS/MS | ≈600 |

| Organic acids | Lactate, Succinate | Ischemia, hypoxia | Krebs cycle | GC-MS | ≈340 |

| Purines | Adenosine, Inosine | Ischemia/reperfusion | Purine metabolism | LC-MS/MS | ≈210 |

| Group № | Title | Examples/Laboratory Biomarkers of Cardiovascular Diseases |

|---|---|---|

| I | Markers of left ventricular function and neuroendocrine activation | Natriuretic peptides/natriuretic hormones *, brain natriuretic peptide (BNP, or NT-proBNP) *, atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) *, Cardiac troponins (hs-cTnT, or troponin T; hs-cTnI, or troponin I) * Copeptin ** Adrenomedullin ** Endothelin-1 ** Melatonin ** |

| II | Inflammatory markers | Adhesion molecules ICAM-1, VCAM-1, ELAM-1 ** Interleukin-1α, -1β, -4, -5, -6, -8, -10, -12, -13, -17, -18, etc. ** Tumor necrosis factor (TNFα) ** Cartilage glycoprotein 39 (YKL-40) ** Soluble CD 40 ligand (sCD40L) ** Transmembrane protein NOTCH1 ** Growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF-15) ** Suppression of tumorigenicity 2 (ST-2) ** Interferon gamma (IFNγ) ** Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase ** |

| III | Hemostasis system markers (coagulation factors) | Fibrinopeptide A ** P-selectin ** Tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) ** Fibrinogen * Homocysteine * Von Willebrand factor (VWF) * Endothelin ** Thrombomodulin ** |

| IV | Predictors of lipid metabolism disorders | Total cholesterol * Very low-, low-, and high-density lipoproteins * Apolipoprotein A1, Apolipoprotein B * Triglycerides * Retinol-binding protein type 4 ** Leptin ** Homocysteine * |

| V | Markers of myocardial fibrosis | Galectin-3 ** Tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases (TIMP-1, -2) ** PICP ** Matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-9, -3) ** Growth stimulating factor (ST2) ** NT-proBNP * Total cholesterol * Low- and high-density lipoproteins * Triglycerides * Collagen IV ** |

| VI | Myocardial necrosis markers | Cardiac troponins (hs-cTnT, or troponin T; hs-cTnI, or troponin I) * Creatine phosphokinase (MB fraction) * Myoglobin * Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) * Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) * ceramides (Cer(d18:1/16:0)) ** |

| VII | Markers of endothelial dysfunction | Homocysteine* Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) ** Endothelin 1–21 ** Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) ** Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) ** Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) ** |

| VIII | Markers of metabolic disorders | Branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) ** Branched-chain α-keto acids (BCKA) ** Leucine ** mTOR activity indicators ** Triglycerides * Dicarboxyacylcarnitines ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhussupbekova, L.; Nurkina, D.; Zhussupova, G.; Smagulova, A.; Rakhmetova, V.; Akhmedyarova, E.; Darybayeva, A.; Kurmangaliyeva, K.; Kukes, I. Diagnostic Potential of Metabolomic and Proteomic Biomarkers in Cardiology—A Narrative Review. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020257

Zhussupbekova L, Nurkina D, Zhussupova G, Smagulova A, Rakhmetova V, Akhmedyarova E, Darybayeva A, Kurmangaliyeva K, Kukes I. Diagnostic Potential of Metabolomic and Proteomic Biomarkers in Cardiology—A Narrative Review. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(2):257. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020257

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhussupbekova, Lazzat, Dinara Nurkina, Gyulnar Zhussupova, Aliya Smagulova, Venera Rakhmetova, Elmira Akhmedyarova, Aisha Darybayeva, Klara Kurmangaliyeva, and Ilya Kukes. 2026. "Diagnostic Potential of Metabolomic and Proteomic Biomarkers in Cardiology—A Narrative Review" Biomedicines 14, no. 2: 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020257

APA StyleZhussupbekova, L., Nurkina, D., Zhussupova, G., Smagulova, A., Rakhmetova, V., Akhmedyarova, E., Darybayeva, A., Kurmangaliyeva, K., & Kukes, I. (2026). Diagnostic Potential of Metabolomic and Proteomic Biomarkers in Cardiology—A Narrative Review. Biomedicines, 14(2), 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020257