Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Comprehensive Review of Risk Factors, Genetics, Diagnosis, and Therapeutic Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Epidemiology

3. Pathogenesis

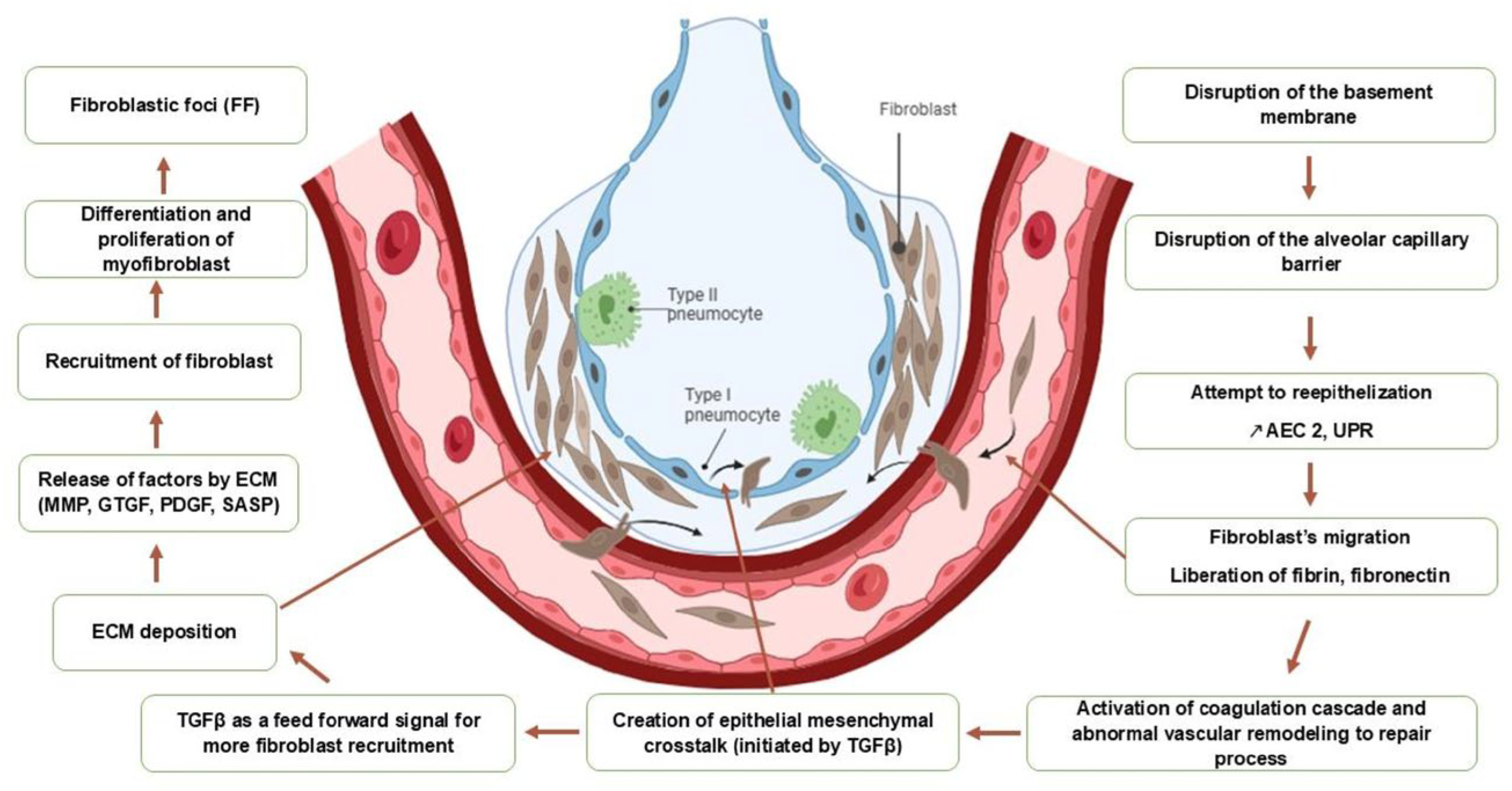

3.1. The Central Role of Alveolar Epithelial Injury on Profibrotic Pathways

3.2. The Role of Epigenetics in Modulating Fibrosis

4. Risk Factors

4.1. Intrinsic Risk Factors

4.1.1. Genetic Predisposition

4.1.2. Age

4.1.3. Male Gender

4.1.4. Microbiome

4.1.5. Gastroesophageal Reflux

4.2. Extrinsic Risk Factors

4.2.1. Smoking

4.2.2. Environmental and/or Professional Exposure

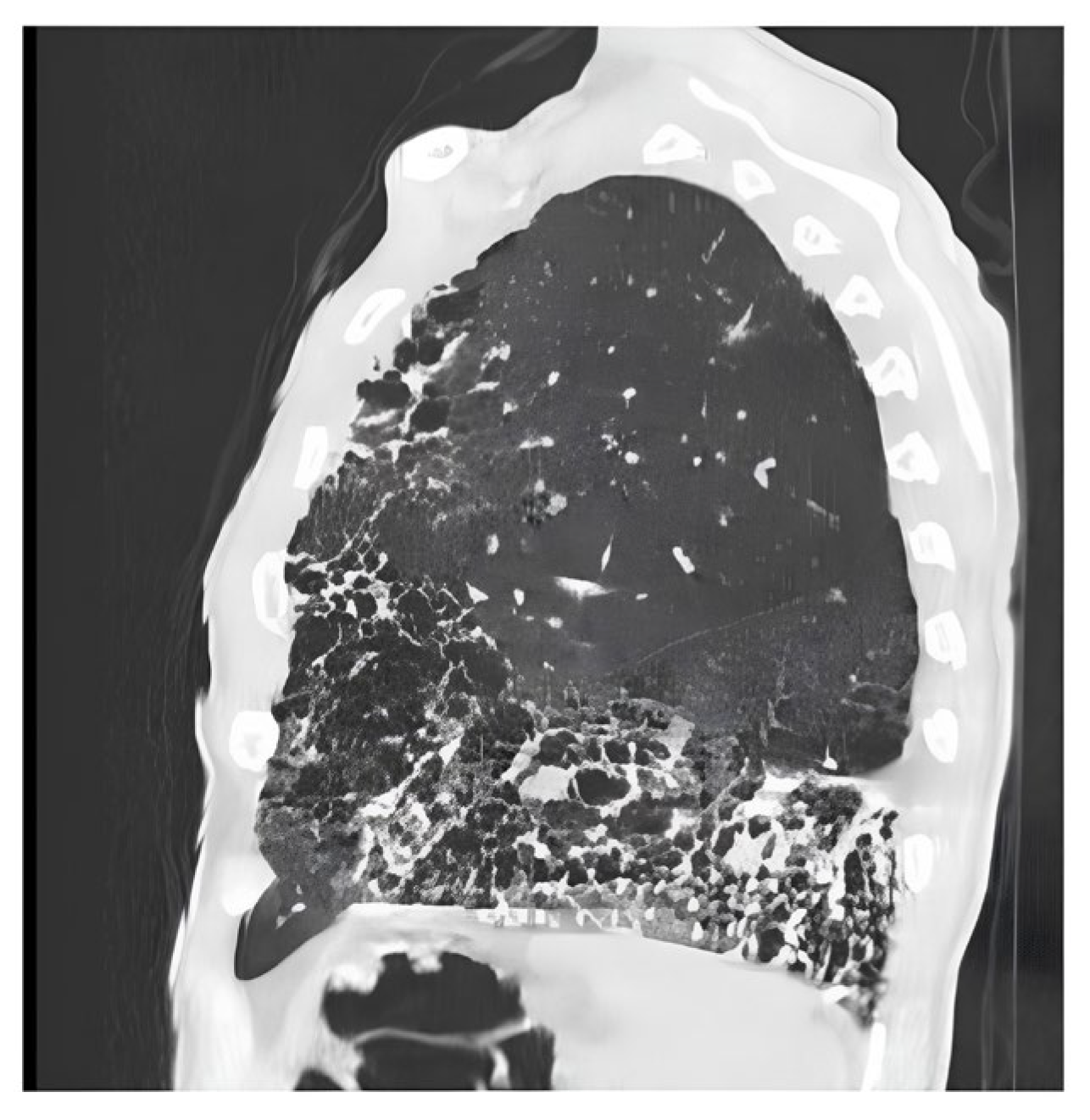

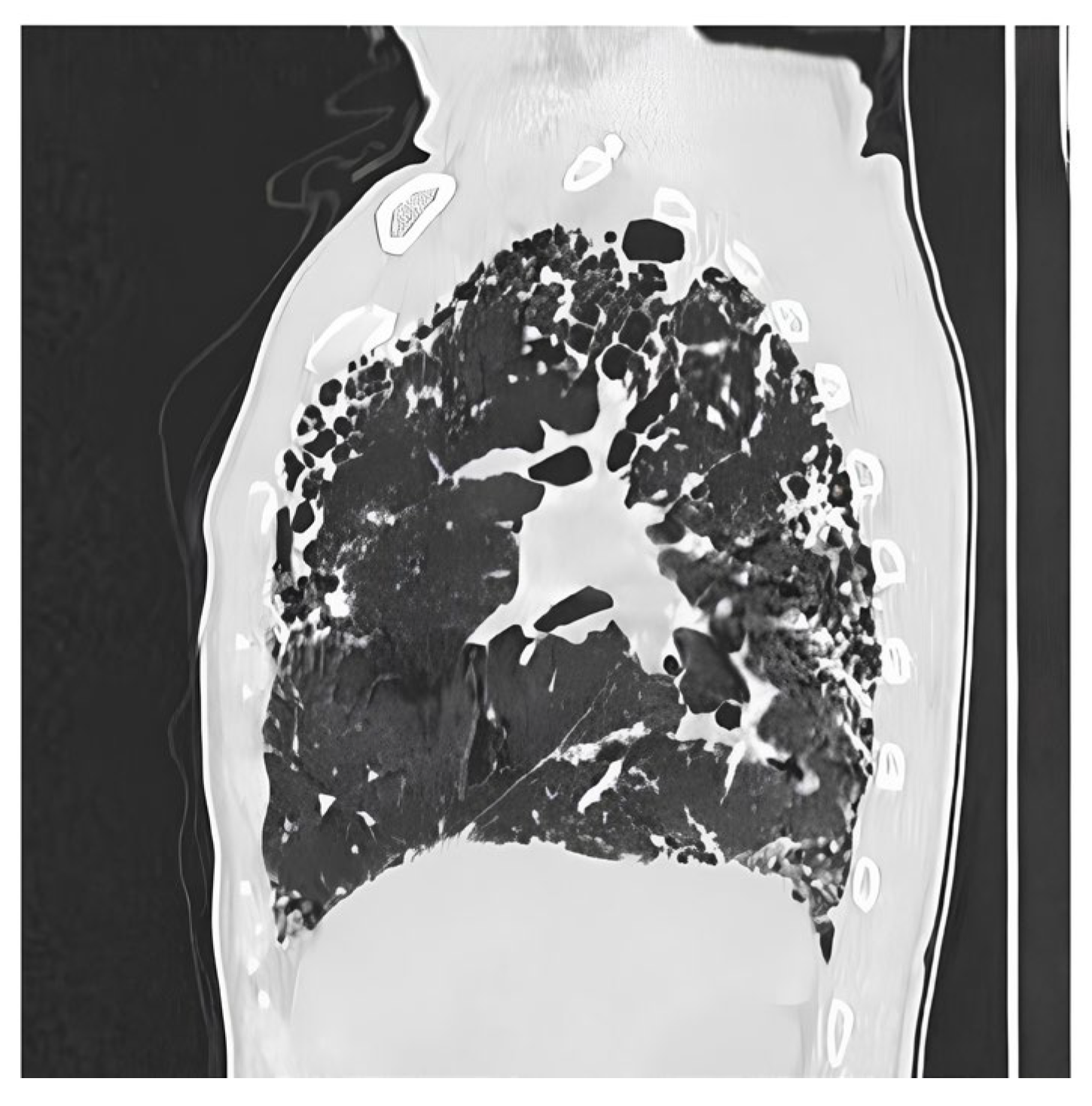

5. Diagnosis

- -

- A scannographic appearance consistent with definite or probable UIP.

- -

- Exclusion of differential diagnoses through comprehensive history-talking and laboratory investigations.

6. Biomarkers: [90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97]

7. Treatment

7.1. Pharmalogical Treatment

7.1.1. Approved Antifibrotic Therapies: (Table 3)

Nintedanib

| Trial Acronym | Drug | Study Design | Primary Endpoint | Key Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAPACITY (1 and 2) | Pirfenidone | Phase 3, randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled (72 weeks) | Change from baseline in percent predicted FVC. | In CAPACITY 2, Pirfenidone significantly reduced the decline in FVC. Pooled data showed a reduction in disease progression. |

| ASCEND | Pirfenidone | Phase 3, randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled (52 weeks) | Change from baseline in percent predicted FVC. | Confirmed the findings of CAPACITY, showing a significant reduction in FVC decline. Pooled analysis with CAPACITY demonstrated a reduction in all-cause mortality. |

| TOMORROW | Nintedanib | Phase 2, randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled (12 months) | Rate of decline in FVC. | Nintedanib (150 mg twice daily) significantly reduced the rate of FVC decline by ~68% and lowered the incidence of acute exacerbations. |

| INPULSIS (1 and 2) | Nintedanib | Phase 3, randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled (52 weeks) | Annual rate of decline in FVC (mL/year). | Both trials met the primary endpoint, showing that Nintedanib slowed FVC decline by ~50% compared to placebo. |

Pirfenidone

- -

- When should treatment be initiated?

- -

- Which antifibrotic agent should be selected?

- -

- Is there a rationale for combining both treatments?

- -

- At what point should treatment be deemed ineffective, necessitating cessation?

Nerandomilast

7.1.2. Investigational Drugs with Promising Results

7.1.3. The Shift Toward Combination and Personalized Therapies

7.2. Non-Pharmacological Treatment

7.2.1. Oxygen Therapy

7.2.2. Pulmonary Rehabilitation

7.2.3. Lung Transplantation

7.2.4. Vaccination

7.3. Treatment of Symptoms

7.3.1. Management of Cough

7.3.2. Management of Dyspnea [8,144]

8. Comorbidities and Complications

8.1. Comorbidities

8.1.1. Respiratory Comorbidities

- ➢

- Combined Pulmonary Fibrosis and Emphysema (CPFE) syndrome

- ➢

- Bronchopulmonary cancer

- ➢

- Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome OSA

8.1.2. Extra Respiratory Comorbidities

- ➢

- Gastroesophageal reflux (GERD)

- ➢

- Other comorbidities

8.2. Complications

8.2.1. Acute Exacerbation of IPF

8.2.2. Pulmonary Hypertension PH

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AE-IPF | Acute Exacerbation of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis |

| ALAT | Latin American Thoracic Association |

| ANA | Antinuclear Antibody |

| ANCA | Anti-Neutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibodies |

| ATP11A | ATPase Phospholipid Transporting 11A |

| ATS | American Thoracic Society |

| BAL | Bronchoalveolar Lavage |

| CPFE | Combined Pulmonary Fibrosis and Emphysema |

| CTGF | Connective Tissue Growth Factor |

| CXCL | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) Ligand |

| DLCO | Diffusing Capacity of the Lungs for Carbon Monoxide |

| DPP9 | Dipeptidyl Peptidase 9 |

| ERS | European Respiratory Society |

| FGF | Fibroblast Growth Factor |

| FVC | Forced Vital Capacity |

| GERD | Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease |

| HRCT | High-Resolution Computed Tomography |

| ILA | Interstitial Lung Abnormality |

| ILD | Interstitial Lung Disease |

| IPF | Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis |

| JRS | The Japanese Respiratory Society |

| KIF15 | Kinesin Family Member 15 |

| KL6 | Krebs von den Lungen-6 |

| LPA | Lysophosphatidic Acid |

| LPA1 | Lysophosphatidic Acid Receptor 1 |

| MAD1L1 | MAD1 Mitotic Arrest Deficient 1 Like 1 |

| MMP | Matrix Metalloproteinase |

| mMRC | Modified Medical Research Council |

| MUC5B | Mucin 5B |

| OSA | Obstructive Sleep Apnea |

| PDGF | Platelet-Derived Growth Factor |

| PFT | Pulmonary Function Test |

| PH | Pulmonary Hypertension |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| SFTPA | Surfactant Protein A |

| SGRQ | St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire |

| SP | Surfactant Protein |

| TERC | Telomerase RNA Component |

| TERT | Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor-Beta |

| TKI | Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor |

| TNIK | TRAF2 and NCK-Interacting Kinase |

| TNFα | Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha |

| TOLLIP | Toll Interacting Protein |

| UIP | Usual Interstitial Pneumonia |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

References

- Patel, H.; Shah, J.R.; Patel, D.R.; Avanthika, C.; Jhaveri, S.; Gor, K. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Diagnosis, biomarkers and newer treatment protocols. Dis. Mon. 2023, 69, 101484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koudstaal, T.; Wijsenbeek, M.S. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Presse Med. 2023, 52, 104166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J.; Fogarty, A.; Hubbard, R.; McKeever, T. Global incidence and mortality of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A systematic review. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 46, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.J.; Collard, H.R.; Pardo, A.; Raghu, G.; Richeldi, L.; Selman, M.; Swigris, J.J.; Taniguchi, H.; Wells, A.U. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchemann, B.; Annesi-Maesano, I.; de Naurois, C.J.; Sanyal, S.; Brillet, P.-Y.; Brauner, M.; Kambouchner, M.; Huynh, S.; Naccache, J.M.; Borie, R.; et al. Prevalence and incidence of interstitial lung diseases in a multi-ethnic county of Greater Paris. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, 1602419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swigris, J.J.; Olson, A.L.; Huie, T.J.; Fernandez-Perez, E.R.; Solomon, J.; Sprunger, D.; Brown, K.K. Ethnic and racial differences in the presence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis at death. Respir. Med. 2012, 106, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elftouh, M.; Amro, L.; Abid, A.; Amara, B.; Kouismi, H.; Benjelloun, A.; Hammi, S.; Zaghba, N.; Serhane, H.; Djahdou, Z.; et al. EPH166 Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF: Epidemiology and Characteristics of Patients in Morocco. Value Health 2022, 25, S223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guide de Pratique Clinique FPI [FPI Clinical Practice Guide]. STMRA. Available online: https://stmra.org/index.php/guidelines (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Sgalla, G.; Iovene, B.; Calvello, M.; Ori, M.; Varone, F.; Richeldi, L. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Pathogenesis and management. Respir. Res. 2018, 19, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, S.L.; Creamer, A.; Hayton, C.; Chaudhuri, N. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF): An Overview. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.K.; Scruggs, A.M.; McEachin, R.C.; White, E.S.; Peters-Golden, M. Lung fibroblasts from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis exhibit genome-wide differences in DNA methylation compared to fibroblasts from nonfibrotic lung. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-U.; Son, J.-H.; Shim, E.-Y.; Cheong, H.S.; Shin, S.-W.; Shin, H.D.; Baek, A.R.; Ryu, S.; Park, C.-S.; Chang, H.S.; et al. Global DNA Methylation Pattern of Fibroblasts in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. DNA Cell Biol. 2019, 38, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio, K.; Singh, I.; Dobersch, S.; Sarvari, P.; Günther, S.; Cordero, J.; Mehta, A.; Wujak, L.; Cabrera-Fuentes, H.; Chao, C.-M.; et al. Inactivation of nuclear histone deacetylases by EP300 disrupts the MiCEE complex in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiao, H.; Zhao, F.; Li, H.; Gao, R.; Yan, B.; Ren, J.; Yang, J. Decrypting the crosstalk of noncoding RNAs in the progression of IPF. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 3169–3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadjicharalambous, M.R.; Lindsay, M.A. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Pathogenesis and the Emerging Role of Long Non-Coding RNAs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Song, M.; Guo, J.; Ma, J.; Qiu, M.; Yang, Z. The function of non-coding RNAs in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Open Med. 2021, 16, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seibold, M.A.; Wise, A.L.; Speer, M.C.; Steele, M.P.; Brown, K.K.; Loyd, J.E.; Fingerlin, T.E.; Zhang, W.; Gudmundsson, G.; Groshong, S.D.; et al. A common MUC5B promoter polymorphism and pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1503–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Noth, I.; Garcia, J.G.; Kaminski, N. A Variant in the Promoter of MUC5B and Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1576–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.G.; Livraghi-Butrico, A.; Fletcher, A.A.; McElwee, M.M.; Evans, S.E.; Boerner, R.M.; Alexander, S.N.; Bellinghausen, L.K.; Song, A.S.; Petrova, Y.M.; et al. Muc5b is required for airway defence. Nature 2014, 505, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Yang, I.V.; Walts, A.D.; Watson, A.M.; Helling, B.A.; Fletcher, A.A.; Lara, A.R.; Schwarz, M.I.; Evans, C.M.; Schwartz, D.A. MUC5B Promoter Variant rs35705950 Affects MUC5B Expression in the Distal Airways in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 193, 464–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horimasu, Y.; Ohshimo, S.; Bonella, F.; Tanaka, S.; Ishikawa, N.; Hattori, N.; Hattori, N.; Kohno, N.; Guzman, J.; Costabel, U. MUC5B promoter polymorphism in Japanese patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology 2015, 20, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peljto, A.L.; Selman, M.; Kim, D.S.; Murphy, E.; Tucker, L.; Pardo, A.; Lee, J.S.; Ji, W.; Schwarz, M.I.; Yang, I.V.; et al. The MUC5B promoter polymorphism is associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in a Mexican cohort but is rare among Asian ancestries. Chest 2015, 147, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhuang, Y.; Guo, W.; Cao, L.; Zhang, H.; Xu, L.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y. Mucin 5B Promoter Polymorphism Is Associated with Susceptibility to Interstitial Lung Diseases in Chinese Males. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Li, W.; Luo, Z.; Chen, Y. The minor T allele of the MUC5B promoter rs35705950 associated with susceptibility to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 24007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Vis, J.; Prasse, A.; Renzoni, E.; Stock, C.; Caliskan, C.; Maher, T.; Bonella, F.; Borie, R.; Crestani, B.; Petrek, M.; et al. Association of mUC5B rs35705950 minor allele with age and survival in European patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 60, 1044. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Goobie, G.C.; Gregory, A.D.; Kass, D.J.; Zhang, Y. Toll-Interacting Protein in Pulmonary Diseases. Abiding by the Goldilocks Principle. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2021, 64, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Kim, S.E.; Chen, T.; Wang, J.; Yang, X.; Tabib, T.; Tan, J.; Guo, B.; Fung, S.; Zhao, J.; et al. Toll interacting protein protects bronchial epithelial cells from bleomycin-induced apoptosis. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 9884–9898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonella, F.; Campo, I.; Zorzetto, M.; Boerner, E.; Ohshimo, S.; Theegarten, D.; Taube, C.; Costabel, U. Potential clinical utility of MUC5B und TOLLIP single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the management of patients with IPF. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldham, J.M.; Ma, S.-F.; Martinez, F.J.; Anstrom, K.J.; Raghu, G.; Schwartz, D.A.; Valenzi, E.; Witt, L.; Lee, C.; Vij, R.; et al. TOLLIP, MUC5B, and the Response to N-Acetylcysteine among Individuals with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 192, 1475–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fingerlin, T.E.; Murphy, E.; Zhang, W.; Peljto, A.L.; Brown, K.K.; Steele, M.P.; Loyd, J.E.; Cosgrove, G.P.; Lynch, D.; Groshong, S.; et al. Genome-wide association study identifies multiple susceptibility loci for pulmonary fibrosis. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 613–620, Erratum in Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 1409. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng1113-1409a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noth, I.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, S.-F.; Flores, C.; Barber, M.; Huang, Y.; Broderick, S.M.; Wade, M.S.; Hysi, P.; Scuirba, J.; et al. Genetic variants associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis susceptibility and mortality: A genome-wide association study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2013, 1, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, R.J.; Oldham, J.M.; A Jenkins, D.; Leavy, O.C.; Guillen-Guio, B.; A Melbourne, C.; Ma, S.-F.; Jou, J.; Kim, J.S.; A Fahy, W.; et al. Longitudinal lung function and gas transfer in individuals with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A genome-wide association study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2023, 11, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partanen, J.J.; Häppölä, P.; Zhou, W.; Lehisto, A.A.; Ainola, M.; Sutinen, E.; Allen, R.J.; Stockwell, A.D.; Leavy, O.C.; Oldham, J.M.; et al. Leveraging global multi-ancestry meta-analysis in the study of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis genetics. Cell Genom. 2022, 2, 100181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-Gonzalez, A.; Tosco-Herrera, E.; Molina-Molina, M.; Flores, C. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and the role of genetics in the era of precision medicine. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1152211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peljto, A.L.; Blumhagen, R.Z.; Walts, A.D.; Cardwell, J.; Powers, J.; Corte, T.J.; Dickinson, J.L.; Glaspole, I.; Moodley, Y.P.; Vasakova, M.K.; et al. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Is Associated with Common Genetic Variants and Limited Rare Variants. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 207, 1194–1202, Erratum in Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 209, 462. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.v209erratum2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Martínez, P.; Blasco, M.A. Replicating through telomeres: A means to an end. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015, 40, 504–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulet, A.; Signes-Costa, J. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Telomeres. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsakiri, K.D.; Cronkhite, J.T.; Kuan, P.J.; Xing, C.; Raghu, G.; Weissler, J.C.; Rosenblatt, R.L.; Shay, J.W.; Garcia, C.K. Adult-onset pulmonary fibrosis caused by mutations in telomerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 7552–7557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armanios, M.Y.; Chen, J.J.-L.; Cogan, J.D.; Alder, J.K.; Ingersoll, R.G.; Markin, C.; Lawson, W.E.; Xie, M.; Vulto, I.; Phillips, J.A.I.; et al. Telomerase Mutations in Families with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1317–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulliamy, T.J.; Walne, A.; Baskaradas, A.; Mason, P.J.; Marrone, A.; Dokal, I. Mutations in the reverse transcriptase component of telomerase (TERT) in patients with bone marrow failure. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2005, 34, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gable, D.L.; Gaysinskaya, V.; Atik, C.C.; Talbot, C.C.; Kang, B.; Stanley, S.E.; Pugh, E.W.; Amat-Codina, N.; Schenk, K.M.; Arcasoy, M.O.; et al. ZCCHC8, the nuclear exosome targeting component, is mutated in familial pulmonary fibrosis and is required for telomerase RNA maturation. Genes Dev. 2019, 33, 1381–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alder, J.K.; Chen, J.J.-L.; Lancaster, L.; Danoff, S.; Su, S.-C.; Cogan, J.D.; Vulto, I.; Xie, M.; Qi, X.; Tuder, R.M.; et al. Short telomeres are a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 13051–13056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronkhite, J.T.; Xing, C.; Raghu, G.; Chin, K.M.; Torres, F.; Rosenblatt, R.L.; Garcia, C.K. Telomere Shortening in Familial and Sporadic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2008, 178, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, B.D.; Lee, J.S.; Kozlitina, J.; Noth, I.; Devine, M.S.; Glazer, C.S.; Torres, F.; Kaza, V.; E Girod, C.; Jones, K.D.; et al. Effect of telomere length on survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: An observational cohort study with independent validation. Lancet Respir. Med. 2014, 2, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, B.D.; Choi, J.; Zaidi, S.; Xing, C.; Holohan, B.; Chen, R.; Choi, M.; Dharwadkar, P.; Torres, F.; E Girod, C.; et al. Exome sequencing links mutations in PARN and RTEL1 with familial pulmonary fibrosis and telomere shortening. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropski, J.A.; Mitchell, D.B.; Markin, C.; Polosukhin, V.V.; Choi, L.; Johnson, J.E.; Lawson, W.E.; Phillips, J.A.; Cogan, J.D.; Blackwell, T.S.; et al. A Novel Dyskerin (DKC1) Mutation Is Associated With Familial Interstitial Pneumonia. Chest 2014, 146, e1–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, S.E.; Gable, D.L.; Wagner, C.L.; Carlile, T.M.; Hanumanthu, V.S.; Podlevsky, J.D.; Khalil, S.E.; DeZern, A.E.; Rojas-Duran, M.F.; Applegate, C.D.; et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the RNA biogenesis factor NAF1 predispose to pulmonary fibrosis–emphysema. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 351ra107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alder, J.K.; Stanley, S.E.; Wagner, C.L.; Hamilton, M.; Hanumanthu, V.S.; Armanios, M. Exome Sequencing Identifies Mutant TINF2 in a Family With Pulmonary Fibrosis. Chest 2015, 147, 1361–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, T.W.; van der Vis, J.J.; van der Smagt, J.J.; Massink, M.P.G.; Grutters, J.C.; van Moorsel, C.H.M. Pulmonary fibrosis linked to variants in the ACD gene, encoding the telomere protein TPP1. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 54, 1900809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borie, R. Fibrose Pulmonaire Idiopathique: De la Génétique à la Clinique [Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: From Genetics to the Clinic]. Doctoral Dissertation, Université Paris Diderot-Paris 7, Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Glasser, J.R.; Mallampalli, R.K. Surfactant and its role in the pathobiology of pulmonary infection. Microbes Infect Inst. Pasteur 2012, 14, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, M.; Wang, Y.; Gerard, R.D.; Mendelson, C.R.; Garcia, C.K. Surfactant Protein A2 Mutations Associated with Pulmonary Fibrosis Lead to Protein Instability and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 22103–22113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, N.; Giraud, V.; Picard, C.; Nunes, H.; Moal, F.D.-L.; Copin, B.; Galeron, L.; De Ligniville, A.; Kuziner, N.; Reynaud-Gaubert, M.; et al. Germline SFTPA1 mutation in familial idiopathic interstitial pneumonia and lung cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016, 25, 1457–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Kuan, P.J.; Xing, C.; Cronkhite, J.T.; Torres, F.; Rosenblatt, R.L.; DiMaio, J.M.; Kinch, L.N.; Grishin, N.V.; Garcia, C.K. Genetic Defects in Surfactant Protein A2 Are Associated with Pulmonary Fibrosis and Lung Cancer. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009, 84, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Moorsel, C.H.M.; Ten Klooster, L.; van Oosterhout, M.F.M.; de Jong, P.A.; Adams, H.; Wouter van Es, H.; Ruven, H.J.T.; van der Vis, J.J.; Grutters, J.C. SFTPA2 Mutations in Familial and Sporadic Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 192, 1249–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, S.; Tanaka, T.; Ishida, M.; Kinoshita, A.; Fukuoka, J.; Takaki, M.; Sakamoto, N.; Ishimatsu, Y.; Kohno, S.; Hayashi, T.; et al. Surfactant protein C G100S mutation causes familial pulmonary fibrosis in Japanese kindred. Eur. Respir. J. 2011, 38, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.Q.; Lane, K.; Phillips, J.; Prince, M.; Markin, C.; Speer, M.; Schwartz, D.A.; Gaddipati, R.; Marney, A.; Johnson, J.; et al. Heterozygosity for a surfactant protein C gene mutation associated with usual interstitial pneumonitis and cellular nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis in one kindred. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 165, 1322–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Moorsel, C.H.M.; van Oosterhout, M.F.M.; Barlo, N.P.; de Jong, P.A.; van der Vis, J.J.; Ruven, H.J.T.; van Es, H.W.; van den Bosch, J.M.M.; Grutters, J.C. Surfactant protein C mutations are the basis of a significant portion of adult familial pulmonary fibrosis in a dutch cohort. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 182, 1419–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulugeta, S.; Nguyen, V.; Russo, S.J.; Muniswamy, M.; Beers, M.F. A Surfactant Protein C Precursor Protein BRICHOS Domain Mutation Causes Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress, Proteasome Dysfunction, and Caspase 3 Activation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2005, 32, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghlan, M.A.; Shifren, A.; Huang, H.J.; Russell, T.D.; Mitra, R.D.; Zhang, Q.; Wegner, D.J.; Cole, F.S.; Hamvas, A. Sequencing of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis-related genes reveals independent single gene associations. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2014, 1, e000057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröner, C.; Wittmann, T.; Reu, S.; Teusch, V.; Klemme, M.; Rauch, D.; Hengst, M.; Kappler, M.; Cobanoglu, N.; Sismanlar, T.; et al. Lung disease caused by ABCA3 mutations. Thorax 2017, 72, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manali, E.D.; Legendre, M.; Nathan, N.; Kannengiesser, C.; Coulomb-L’HErmine, A.; Tsiligiannis, T.; Tomos, P.; Griese, M.; Borie, R.; Clement, A.; et al. Bi-allelic missense ABCA3 mutations in a patient with childhood ILD who reached adulthood. ERJ Open Res. 2019, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, T.; Lee, J.S. Risk factors for the development of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A review. Curr. Pulmonol. Rep. 2018, 7, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, M.; Calyeca, J.; Rojas, M.; Mora, A.L. Mitochondria dysfunction and metabolic reprogramming as drivers of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Redox Biol. 2020, 33, 101509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.K.; Zhou, Y.; Murray, S.; Tayob, N.; Noth, I.; Lama, V.N.; Moore, B.B.; White, E.S.; Flaherty, K.R.; Huffnagle, G.B.; et al. Lung microbiome and disease progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: An analysis of the COMET study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2014, 2, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amati, F.; Stainer, A.; Mantero, M.; Gramegna, A.; Simonetta, E.; Suigo, G.; Voza, A.; Nambiar, A.M.; Cariboni, U.; Oldham, J.; et al. Lung Microbiome in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Other Interstitial Lung Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo, P.; Molyneaux, P.L.; Bernardinello, N.; Cocconcelli, E.; Biondini, D.; Fracasso, F.; Tiné, M.; Saetta, M.; Maher, T.M.; Balestro, E. The Role of the Lung’s Microbiome in the Pathogenesis and Progression of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickson, R.P.; Huffnagle, G.B. The Lung Microbiome: New Principles for Respiratory Bacteriology in Health and Disease. PLOS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, G.; Freudenberger, T.D.; Yang, S.; Curtis, J.R.; Spada, C.; Hayes, J.; Sillery, J.K.; Pope, C.E.; Pellegrini, C.A. High prevalence of abnormal acid gastro-oesophageal reflux in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2006, 27, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Collard, H.R.; Anstrom, K.J.; Martinez, F.J.; Noth, I.; Roberts, R.S.; Yow, E.; Raghu, G. Anti-acid treatment and disease progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: An analysis of data from three randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir. Med. 2013, 1, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuter, M.; Wuyts, W.; Renzoni, E.; Koschel, D.; Maher, T.M.; Kolb, M.; Weycker, D.; Spagnolo, P.; Kirchgaessler, K.-U.; Herth, F.J.F.; et al. Antacid therapy and disease outcomes in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A pooled analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2016, 4, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, T.H.G.; Paliogiannis, P.; Nasrallah, G.K.; Giordo, R.; Eid, A.H.; Fois, A.G.; Zinellu, A.; Mangoni, A.A.; Pintus, G. Emerging cellular and molecular determinants of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 78, 2031–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottin, V.; Bonniaud, P.; Cadranel, J.; Crestani, B.; Jouneau, S.; Marchand-Adam, S.; Hachulla, E.; Arnaud, L.; Pellegrin, J.-L.; Valeyre, D.; et al. Recommandations pratiques pour le diagnostic et la prise en charge de la fibrose pulmonaire idiopathique—Actualisation 2021. Version intégrale [Practical recommendations for the diagnosis and management of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis—Updated 2021. Full version]. Rev. Mal. Respir. 2022, 39, e35–e106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wakwaya, Y.; Brown, K.K. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Epidemiology, Diagnosis andOutcomes. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 357, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillard, F. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Available online: https://radiopaedia.org/cases/idiopathic-pulmonary-fibrosis-5?case_id=idiopathic-pulmonary-fibrosis-5 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Raghu, G.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Richeldi, L.; Thomson, C.C.; Inoue, Y.; Johkoh, T.; Kreuter, M.; Lynch, D.A.; Maher, T.M.; Martinez, F.J.; et al. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (an Update) and Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis in Adults: An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 205, e18–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, C.A.; Müller, N.L.; Lee, K.S.; Johkoh, T.; Mitsuhiro, H.; Chong, S. Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias: Prevalence of Mediastinal Lymph Node Enlargement in 206 Patients. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2006, 186, 995–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruden, J.F.; Green, D.B.; Legasto, A.C.; Jensen, E.A.; Panse, P.M. Dendriform Pulmonary Ossification in the Absence of Usual Interstitial Pneumonia: CT Features and Possible Association with Recurrent Acid Aspiration. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2017, 209, 1209–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egashira, R.; Jacob, J.; Kokosi, M.A.; Brun, A.-L.; Rice, A.; Nicholson, A.G.; Wells, A.U.; Hansell, D.M. Diffuse Pulmonary Ossification in Fibrosing Interstitial Lung Diseases: Prevalence and Associations. Radiology 2017, 284, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, T.L.; Tominaga, M.; Hansell, D.M.; von der Thusen, J.; Rassl, D.; Parfrey, H.; Guy, S.; Twentyman, O.; Rice, A.; Maher, T.M.; et al. Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis: A spectrum of histopathological and imaging phenotypes. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 40, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Myers, J.L.; Richeldi, L.; Ryerson, C.J.; Lederer, D.J.; Behr, J.; Cottin, V.; Danoff, S.K.; Morell, F.; et al. Diagnosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, e44–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallaert, B.; Uzunhan, Y. Épidémiologie et diagnostic de la fibrose pulmonaire idiopathique (FPI). Rev. Mal. Resp. 2019, 3, S104–S106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J.P.; Fogarty, A.W.; McKeever, T.M.; Hubbard, R.B. In-Hospital Mortality after Surgical Lung Biopsy for Interstitial Lung Disease in the United States. 2000 to 2011. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 193, 1161–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J.P.; McKeever, T.M.; Fogarty, A.W.; Navaratnam, V.; Hubbard, R.B. Surgical lung biopsy for the diagnosis of interstitial lung disease in England: 1997–2008. Eur. Respir. J. 2016, 48, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Kim, D.K.; Kim, D.S.; Koh, Y.; Lee, S.D.; Kim, W.S.; Kim, W.D.; Park, S.I. Mortality and risk factors for surgical lung biopsy in patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2007, 31, 1115–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, D.A.; Sverzellati, N.; Travis, W.D.; Brown, K.K.; Colby, T.V.; Galvin, J.R.; Goldin, J.G.; Hansell, D.M.; Inoue, Y.; Johkoh, T.; et al. Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A Fleischner Society White Paper. Lancet Respir. Med. 2018, 6, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, R.; Raparia, K.; Lynch, D.A.; Brown, K.K. Surgical Lung Biopsy for Interstitial Lung Diseases. Chest 2017, 151, 1131–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Johannson, K.; Marcoux, V.S.; E Ronksley, P.; Ryerson, C.J. Diagnostic Yield and Complications of Transbronchial Lung Cryobiopsy for Interstitial Lung Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016, 13, 1828–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podolanczuk, A.J.; Thomson, C.C.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Richeldi, L.; Martinez, F.J.; Kolb, M.; Raghu, G. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: State of the art for 2023. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 61, 2200957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.; Kim, J.; Cho, H.S.; Kim, H.C. Baseline serum Krebs von den Lungen-6 as a biomarker for the disease progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloisio, E.; Braga, F.; Puricelli, C.; Panteghini, M. Prognostic role of Krebs von den Lungen-6 (KL-6) measurement in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2021, 59, 1400–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirfenidone Clinical Study Group in Japan; Ikeda, K.; Chiba, H.; Nishikiori, H.; Azuma, A.; Kondoh, Y.; Ogura, T.; Taguchi, Y.; Ebina, M.; Sakaguchi, H.; et al. Serum surfactant protein D as a predictive biomarker for the efficacy of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A post-hoc analysis of the phase 3 trial in Japan. Respir. Res. 2020, 21, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Peng, F.; Zhou, Y. Biomarkers in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Current insight and future direction. Chin. Med J. Pulm. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 2, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karampitsakos, T.; Juan-Guardela, B.M.; Tzouvelekis, A.; Herazo-Maya, J.D. Precision medicine advances in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. eBioMedicine 2023, 95, 104766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Liu, C.; Tan, C.; Zhang, J. Predictive biomarkers of disease progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankovic, S.; Stjepanovic, M.; Asanin, M. Biomarkers in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. In Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegunsoye, A.; Alqalyoobi, S.; Linderholm, A.; Bowman, W.S.; Lee, C.T.; Pugashetti, J.V.; Sarma, N.; Ma, S.-F.; Haczku, A.; Sperling, A.; et al. Circulating Plasma Biomarkers of Survival in Antifibrotic-Treated Patients With Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Chest 2020, 158, 1526–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spagnolo, P.; Kropski, J.A.; Jones, M.G.; Lee, J.S.; Rossi, G.; Karampitsakos, T.; Maher, T.M.; Tzouvelekis, A.; Ryerson, C.J. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Disease mechanisms and drug development. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 222, 107798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richeldi, L.; Costabel, U.; Selman, M.; Kim, D.S.; Hansell, D.M.; Nicholson, A.G.; Brown, K.K.; Flaherty, K.R.; Noble, P.W.; Raghu, G.; et al. Efficacy of a Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 1079–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richeldi, L.; Du Bois, R.M.; Raghu, G.; Azuma, A.; Brown, K.K.; Costabel, U.; Cottin, V.; Flaherty, K.R.; Hansell, D.M.; Inoue, Y.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Nintedanib in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 2071–2082, Erratum in N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 782. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMx150012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richeldi, L.; Kolb, M.; Jouneau, S.; Wuyts, W.A.; Schinzel, B.; Stowasser, S.; Quaresma, M.; Raghu, G. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in patients with advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. BMC Pulm. Med. 2020, 20, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richeldi, L.; Cottin, V.; du Bois, R.M.; Selman, M.; Kimura, T.; Bailes, Z.; Schlenker-Herceg, R.; Stowasser, S.; Brown, K.K. Nintedanib in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Combined evidence from the TOMORROW and INPULSIS® trials. Respir. Med. 2016, 113, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruwanpura, S.M.; Thomas, B.J.; Bardin, P.G. Pirfenidone: Molecular Mechanisms and Potential Clinical Applications in Lung Disease. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2020, 62, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, P.W.; Albera, C.; Bradford, W.Z.; Costabel, U.; Glassberg, M.K.; Kardatzke, D.; King, T.E., Jr.; Lancaster, L.; Sahn, S.A.; Szwarcberg, J.; et al. Pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CAPACITY): Two randomised trials. Lancet 2011, 377, 1760–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, T.E., Jr.; Bradford, W.Z.; Castro-Bernardini, S.; Fagan, E.A.; Glaspole, I.; Glassberg, M.K.; Gorina, E.; Hopkins, P.M.; Kardatzke, D.; Lancaster, L.; et al. A Phase 3 Trial of Pirfenidone in Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 2083–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, P.W.; Albera, C.; Bradford, W.Z.; Costabel, U.; du Bois, R.M.; Fagan, E.A.; Fishman, R.S.; Glaspole, I.; Glassberg, M.K.; Lancaster, L.; et al. Pirfenidone for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Analysis of pooled data from three multinational phase 3 trials. Eur. Respir. J. 2016, 47, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley, B.; Swigris, J.; Day, B.-M.; Stauffer, J.L.; Raimundo, K.; Chou, W.; Collard, H.R. Pirfenidone Reduces Respiratory-related Hospitalizations in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 196, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, S.D.; Costabel, U.; Glaspole, I.; Glassberg, M.K.; Lancaster, L.H.; Lederer, D.J.; Pereira, C.A.; Trzaskoma, B.; Morgenthien, E.A.; Limb, S.L.; et al. Efficacy of Pirfenidone in the Context of Multiple Disease Progression Events in Patients With Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Chest 2019, 155, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, T.M.; Molina-Molina, M.; Russell, A.-M.; Bonella, F.; Jouneau, S.; Ripamonti, E.; Axmann, J.; Vancheri, C. Unmet needs in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis―insights from patient chart review in five European countries. BMC Pulm. Med. 2017, 17, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, T.M.; Swigris, J.J.; Kreuter, M.; Wijsenbeek, M.; Cassidy, N.; Ireland, L.; Axmann, J.; Nathan, S.D. Identifying Barriers to Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Treatment: A Survey of Patient and Physician Views. Respiration 2018, 96, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Martino, E.; Provenzani, A.; Vitulo, P.; Polidori, P. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Pirfenidone, Nintedanib, and Pamrevlumab for the Treatment of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Ann. Pharmacother. 2021, 55, 723–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vancheri, C.; Kreuter, M.; Richeldi, L.; Ryerson, C.J.; Valeyre, D.; Grutters, J.C.; Wiebe, S.; Stansen, W.; Quaresma, M.; Stowasser, S.; et al. Nintedanib with Add-on Pirfenidone in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Results of the INJOURNEY Trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 197, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, S.D.; Albera, C.; Costabel, U.; Glaspole, I.; Glassberg, M.; Lancaster, L.; Lederer, D.J.; Pereira, C.A.; Swigris, J.; Day, B.-M.; et al. Effect of Continued Treatment with Pirfenidone Following a ≥10% Relative Decline in Percent Predicted Forced Vital Capacity in Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 193, A499. [Google Scholar]

- Wuyts, W.A.; Kolb, M.; Stowasser, S.; Stansen, W.; Huggins, J.T.; Raghu, G. First Data on Efficacy and Safety of Nintedanib in Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Forced Vital Capacity of ≤50% of Predicted Value. Lung 2016, 194, 739–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubbara, A.; Amundson, W.H.; Herman, A.; Lee, A.M.; Bishop, J.R.; Kim, H.J. Genetic variations in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and patient response to pirfenidone. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lleu, P.L.; Cottin, V.; Richeldi, L.; Assassi, S.; Azuma, A.; Hoffmann-Vold, A.M.; Kreuter, M.; Liu, Y.; Maher, T.M.; Oldham, J.M.; et al. Caractéristiques initiales des patients inclus dans FIBRONEERTM-IPF, essai de phase III randomisé, contrôlé vs placebo de l’inhibiteur préférentiel PDE4B, nerandomilast, chez des patients atteints d’une FPI. Rev. Mal. Respir. Actual. 2025, 17, 295–297. [Google Scholar]

- Reininger, D.; Fundel-Clemens, K.; Mayr, C.H.; Wollin, L.; Laemmle, B.; Quast, K.; Nickolaus, P.; Herrmann, F.E. PDE4B inhibition by nerandomilast: Effects on lung fibrosis and transcriptome in fibrotic rats and on biomarkers in human lung epithelial cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 181, 4766–4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richeldi, L.; Azuma, A.; Cottin, V.; Kreuter, M.; Maher, T.M.; Martinez, F.J.; Oldham, J.M.; Valenzuela, C.; Clerisme-Beaty, E.; Gordat, M.; et al. Nerandomilast in Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 2193–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richeldi, L.; Azuma, A.; Cottin, V.; Kreuter, M.; Maher, T.; Martinez, F.; Oldham, J.; Valenzuela, C.; Clerisme-Beaty, E.; Gordat, M.; et al. Phase III FIBRONEER-IPF Trial of Nerandomilast in Patients With Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2025, 211, A7993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouvry, D. Des essais cliniques négatifs et des molécules prometteuses: Le point sur les nouvelles thérapeutiques de la fibrose pulmonaire idiopathique. Rev. Mal. Resp. 2018, 10, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Liu, S.; Li, S.; Xia, Y. Targeting Growth Factor and Cytokine Pathways to Treat Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 918771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, S.M.; Snyder, L.; Todd, J.L.; Soule, B.; Christian, R.; Anstrom, K.; Luo, Y.; Gagnon, R.; Rosen, G. Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 2 Trial of BMS-986020, a Lysophosphatidic Acid Receptor Antagonist for the Treatment of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Chest 2018, 154, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathan, S.D.; Behr, J.; Cottin, V.; Lancaster, L.; Smith, P.; Deng, C.; Pearce, N.; Bell, H.; Peterson, L.; Flaherty, K.R. Study design and rationale for the TETON phase 3, randomised, controlled clinical trials of inhaled treprostinil in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2022, 9, e001310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzouvelekis, A.; Paspaliaris, V.; Koliakos, G.; Ntolios, P.; Bouros, E.; Oikonomou, A.; Zissimopoulos, A.; Boussios, N.; Dardzinski, B.; Gritzalis, D.; et al. A prospective, non-randomized, no placebo-controlled, phase Ib clinical trial to study the safety of the adipose derived stromal cells-stromal vascular fraction in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J. Transl. Med. 2013, 11, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntolios, P.; Manoloudi, E.; Tzouvelekis, A.; Bouros, E.; Steiropoulos, P.; Anevlavis, S.; Bouros, D.; Froudarakis, M.E. Longitudinal outcomes of patients enrolled in a phase Ib clinical trial of the adipose-derived stromal cells-stromal vascular fraction in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Clin. Respir. J. 2018, 12, 2084–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassberg, M.K.; Minkiewicz, J.; Toonkel, R.L.; Simonet, E.S.; Rubio, G.A.; DiFede, D.; Shafazand, S.; Khan, A.; Pujol, M.V.; LaRussa, V.F.; et al. Allogeneic Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Patients With Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis via Intravenous Delivery (AETHER). Chest 2017, 151, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, D.S.; Chew, T.; Flaherty, K.R.; Frye, S.; Gibson, K.F.; Kaminski, N.; Klemsz, M.J.; Lange, W.; Noth, I.; Rothhaar, K. Oral immunotherapy with type V collagen in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 45, 1393–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richeldi, L.; Pérez, E.R.F.; Costabel, U.; Albera, C.; Lederer, D.J.; Flaherty, K.R.; Ettinger, N.; Perez, R.; Scholand, M.B.; Goldin, J.; et al. Pamrevlumab, an anti-connective tissue growth factor therapy, for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (PRAISE): A phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, L.; Cottin, V.; Ramaswamy, M.; Wuyts, W.A.; Jenkins, R.G.; Scholand, M.B.; Kreuter, M.; Valenzuela, C.; Ryerson, C.J.; Goldin, J.; et al. Bexotegrast in Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: The INTEGRIS-IPF Clinical Trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 210, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, J.J.; Jacobs, S.; Lefebvre, É.A.; Cosgrove, G.P.; Clark, A.; Turner, S.M.; Decaris, M.; Barnes, C.N.; Jurek, M.; Williams, B.; et al. Bexotegrast Shows Dose-Dependent Integrin αvβ6 Receptor Occupancy in Lungs of Participants with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Phase 2, Open-Label Clinical Trial. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2022, 22, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corte, T.J.; Behr, J.; Cottin, V.; Glassberg, M.K.; Kreuter, M.; Martinez, F.J.; Ogura, T.; Suda, T.; Wijsenbeek, M.; Berkowitz, E.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Admilparant, an LPA1 Antagonist, in Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2025, 211, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Ren, F.; Wang, P.; Cao, J.; Tan, C.; Ma, D.; Zhao, L.; Dai, J.; Ding, Y.; Fang, H.; et al. A generative AI-discovered TNIK inhibitor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A randomized phase 2a trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 2602–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, A.; Chaudhuri, N.; Barczyk, A.; Wilsher, M.L.; Hopkins, P.; Glaspole, I.; Corte, T.J.; Šterclová, M.; Veale, A.; Jassem, E.; et al. Inhaled pirfenidone solution (AP01) for IPF: A randomised, open-label, dose–response trial. Thorax 2023, 78, 882–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krempaska, K.; Barnowski, S.; Gavini, J.; Hobi, N.; Ebener, S.; Simillion, C.; Stokes, A.; Schliep, R.; Knudsen, L.; Geiser, T.K.; et al. Azithromycin has enhanced effects on lung fibroblasts from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) patients compared to controls. Respir. Res. 2020, 21, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behr, J.; Bendstrup, E.; Crestani, B.; Günther, A.; Olschewski, H.; Sköld, C.M.; Wells, A.; Wuyts, W.; Koschel, D.; Kreuter, M.; et al. Safety and tolerability of acetylcysteine and pirfenidone combination therapy in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2016, 4, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, S.; Kataoka, K.; Kondoh, Y.; Kato, M.; Okamoto, M.; Mukae, H.; Bando, M.; Suda, T.; Yatera, K.; Tanino, Y.; et al. Pirfenidone plus inhaled N-acetylcysteine for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A randomised trial. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 57, 2000348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Holland, A.; Hill, C.J.; Conron, M.; Munro, P.; McDonald, C.F. Short term improvement in exercise capacity and symptoms following exercise training in interstitial lung disease. Thorax 2008, 63, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, O.; Kondoh, Y.; Kimura, T.; Kato, K.; Kataoka, K.; Ogawa, T.; Watanabe, F.; Arizono, S.; Nishimura, K.; Taniguchi, H. Effects of pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology 2008, 13, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainshelboim, B.; Oliveira, J.; Yehoshua, L.; Weiss, I.; Fox, B.D.; Fruchter, O.; Kramer, M.R. Exercise Training-Based Pulmonary Rehabilitation Program Is Clinically Beneficial for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Respiration 2014, 88, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, A.E.; Hill, C. Physical training for interstitial lung disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, 8, CD006322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, D.C.; Cherikh, W.S.; Harhay, M.O.; Hayes, D.; Hsich, E.; Khush, K.K.; Meiser, B.; Potena, L.; Rossano, J.W.; Toll, A.E.; et al. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-sixth adult lung and heart–lung transplantation Report—2019; Focus theme: Donor and recipient size match. J. Heart Lung Transplant 2019, 38, 1042–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenhorst, G.; Remschmidt, C.; Harder, T.; Hummers-Pradier, E.; Wichmann, O.; Bogdan, C. Effectiveness of the 23-Valent Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccine (PPV23) against Pneumococcal Disease in the Elderly: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnave, C.; Mertens, D.; Peetermans, W.; Cobbaert, K.; Ghesquiere, B.; Deschodt, M.; Flamaing, J. Adult vaccination for pneumococcal disease: A comparison of the national guidelines in Europe. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 38, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blin, E.; Wallaert, B. Traitement de la fibrose pulmonaire idiopathique: Prendre en charge les symptômes. Rev. Mal. Resp. 2016, 8, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, M.R.; Santopietro, V.; Mathew, L.; Horton, K.M.; Polito, A.J.; Liu, M.C.; Danoff, S.K.; Lechtzin, N. Thalidomide for the Treatment of Cough in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012, 157, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dacosta-Noble, P.; Valeyre, D. Fibrose pulmonaire idiopathique: Les comorbidités. Rev. Mal. Resp. 2016, 8, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauleda, J.; Núñez, B.; Sala, E.; Soriano, J.B. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Epidemiology, Natural History, Phenotypes. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luppi, F.; Kalluri, M.; Faverio, P.; Kreuter, M.; Ferrara, G. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis beyond the lung: Understanding disease mechanisms to improve diagnosis and management. Respir. Res. 2021, 22, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuter, M.; Wijsenbeek, M.S.; Vasakova, M.; Spagnolo, P.; Kolb, M.; Costabel, U.; Weycker, D.; Kirchgaessler, K.-U.; Maher, T.M. Unfavourable effects of medically indicated oral anticoagulants on survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Methodological concerns. Eur. Respir. J. 2016, 48, 1524–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, N.; Takasaka, N.; Yoshida, M.; Tsubouchi, K.; Minagawa, S.; Araya, J.; Saito, N.; Fujita, Y.; Kurita, Y.; Kobayashi, K.; et al. Metformin attenuates lung fibrosis development via NOX4 suppression. Respir. Res. 2016, 17, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangarajan, S.; Bone, N.B.; Zmijewska, A.A.; Jiang, S.; Park, D.W.; Bernard, K.; Locy, M.L.; Ravi, S.; Deshane, J.; Mannon, R.B.; et al. Metformin reverses established lung fibrosis in a bleomycin model. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1121–1131, Erratum in Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1627. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0170-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jouneau, S.; Kerjouan, M.; Rousseau, C.; Lederlin, M.; Llamas-Guttierez, F.; De Latour, B.; Guillot, S.; Vernhet, L.; Desrues, B.; Thibault, R. What are the best indicators to assess malnutrition in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients? A cross-sectional study in a referral center. Nutrition 2019, 62, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collard, H.R.; Ryerson, C.J.; Corte, T.J.; Jenkins, G.; Kondoh, Y.; Lederer, D.J.; Lee, J.S.; Maher, T.M.; Wells, A.U.; Antoniou, K.M.; et al. Acute Exacerbation of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An International Working Group Report. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 194, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biondini, D.; Balestro, E.; Sverzellati, N.; Cocconcelli, E.; Bernardinello, N.; Ryerson, C.J.; Spagnolo, P. Acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (AE-IPF): An overview of current and future therapeutic strategies. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2020, 14, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishaba, T. Acute Exacerbation of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Medicina 2019, 55, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Clin. Chest Med. 2012, 33, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collard, H.R.; Yow, E.; Richeldi, L.; Anstrom, K.J.; Glazer, C.; IPFnet Investigators. Suspected acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis as an outcome measure in clinical trials. Respir. Res. 2013, 14, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.W.; Hong, S.-B.; Lim, C.-M.; Koh, Y.; Kim, D.S. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Incidence, risk factors and outcome. Eur. Respir. J. 2011, 37, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondoh, Y.; Taniguchi, H.; Katsuta, T.; Kimura, T.; Kataoka, K.; Taga, S.; Johkoh, T.; Kitaichi, M. Risk factors of acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc. Diffuse Lung Dis. 2010, 27, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jeon, K.; Chung, M.P.; Lee, K.S.; Chung, M.J.; Han, J.; Koh, W.-J.; Suh, G.Y.; Kim, H.; Kwon, O.J. Prognostic factors and causes of death in Korean patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Med. 2006, 100, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natsuizaka, M.; Chiba, H.; Kuronuma, K.; Otsuka, M.; Kudo, K.; Mori, M.; Bando, M.; Sugiyama, Y.; Takahashi, H. Epidemiologic Survey of Japanese Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Investigation of Ethnic Differences. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 190, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Chen, Y.; Ye, Q. Risk factors for acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Respir. J. 2017, 12, 1084–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schupp, J.C.; Binder, H.; Jäger, B.; Cillis, G.; Zissel, G.; Müller-Quernheim, J.; Prasse, A. Macrophage activation in acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisa, M.; Marinelli, C.; Savarino, V.; Savarino, E. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and GERD: Links and risks. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2019, ume 15, 1081–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, K.; Ishimoto, H.; Yamada, S.; Kushima, H.; Ishii, H.; Imanaga, T.; Harada, T.; Ishimatsu, Y.; Matsumoto, N.; Naito, K.; et al. Autopsy analyses in acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Res. 2014, 15, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wootton, S.C.; Kim, D.S.; Chiu, C.; Kondoh, Y.; Lee, J.S.; Kistler, A.; Ganem, D.; DeRisi, J.; Collard, H.R. Occult Viral Infection In Acute Exacerbation Of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 183, 1698–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naccache, J.-M.; Montil, M.; Cadranel, J.; Cachanado, M.; Cottin, V.; Crestani, B.; Valeyre, D.; Wallaert, B.; Simon, T.; Nunes, H. Study protocol: Exploring the efficacy of cyclophosphamide added to corticosteroids for treating acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-center phase III trial (EXAFIP). BMC Pulm. Med. 2019, 19, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naccache, J.-M.; Jouneau, S.; Didier, M.; Borie, R.; Cachanado, M.; Bourdin, A.; Reynaud-Gaubert, M.; Bonniaud, P.; Israël-Biet, D.; Prévot, G.; et al. Cyclophosphamide added to glucocorticoids in acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (EXAFIP): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, K.; Ichikado, K.; Yasuda, Y.; Anan, K.; Suga, M. Azithromycin for idiopathic acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A retrospective single-center study. BMC Pulm. Med. 2017, 17, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, K.; Yatera, K.; Fujino, Y.; Ishimoto, H.; Nakao, H.; Hanaka, T.; Ogoshi, T.; Kido, T.; Fushimi, K.; Matsuda, S.; et al. Efficacy of concurrent treatments in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients with a rapid progression of respiratory failure: An analysis of a national administrative database in Japan. BMC Pulm. Med. 2016, 16, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petnak, T.; Lertjitbanjong, P.; Thongprayoon, C.; Moua, T. Impact of Antifibrotic Therapy on Mortality and Acute Exacerbation in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Chest 2021, 160, 1751–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G.; Behr, J.; Brown, K.K.; Egan, J.J.; Kawut, S.M.; Flaherty, K.R.; Martinez, F.J.; Nathan, S.D.; Wells, A.U.; Collard, H.R.; et al. Treatment of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis with Ambrisentan. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 158, 641–649, Erratum in Ann. Intern. Med. 2014, 160, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behr, J.; Nathan, S.D.; A Wuyts, W.; Bishop, N.M.; E Bouros, D.; Antoniou, K.; Guiot, J.; Kramer, M.R.; Kirchgaessler, K.-U.; Bengus, M.; et al. Efficacy and safety of sildenafil added to pirfenidone in patients with advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and risk of pulmonary hypertension: A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2b trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.K.; Bach, D.S.; Hagan, P.G.; Yow, E.; Flaherty, K.R.; Toews, G.B.; Anstrom, K.J.; Martinez, F.J. Sildenafil Preserves Exercise Capacity in Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Right-sided Ventricular Dysfunction. Chest 2013, 143, 1699–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Variant Type | Associated Pathway/Function | Key Findings in IPF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common Variants (Allele Frequency > 1%) | |||

| MUC5B [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25] | Common (rs35705950) | Mucin production; host defense | The strongest genetic risk factor for both familial and sporadic IPF. The T allele leads to MUC5B overexpression, mucociliary dysfunction, and ER stress. Paradoxically, carriers of the T allele are associated with better survival outcomes. |

| TOLLIP [26,27,28,29] | Common (rs5743890, rs3750920) | Innate immunity (Toll-like receptor signaling) | Modulates inflammatory responses. The minor allele of rs5743890 is linked to poorer survival and faster disease progression. The rs3750920 variant shows a significant interaction with N-acetylcysteine (NAC) therapy. |

| FAM13A [30,31,32,33] | Common | Wnt signaling | Identified in GWAS as a susceptibility locus. |

| DSP [30,31,32,33] | Common | Cell adhesion | Identified in GWAS as a susceptibility locus. |

| OBFC1 [30,31,32,33] | Common | DNA repair; telomere maintenance | Identified in GWAS as a susceptibility locus. |

| ATP11A [30,31,32,33] | Common | Unknown in IPF context | Identified in GWAS as a susceptibility locus. |

| DPP9 [30,31,32,33] | Common | Inflammation | Identified in GWAS as a susceptibility locus. |

| SPPL2C [30,31,32,33] | Common | Unknown in IPF context | Identified in GWAS as a susceptibility locus. |

| PKN2 [30,31,32,33] | Common | Unknown in IPF context | A variant has been associated with disease progression, potentially revealing a new biological mechanism. |

| GPR157, DNAJB4/GIPC2, RAPGEF2, FKBP5, RP11286H14.4, PSKH1, FUT6 [30,31,32,33] | Common | Various | Identified as novel susceptibility loci in a large multi-ancestry meta-analysis. |

| Rare Variants (Allele Frequency < 1%) | |||

| Telomere-Related Genes | |||

| TERT, TERC [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] | Rare | Telomere maintenance (telomerase components) | Monoallelic mutations cause telomere shortening, leading to premature cellular senescence and impaired epithelial repair. Found in a significant portion of familial IPF cases. |

| RTEL1, PARN [45] | Rare | Telomere maintenance | Mutations also lead to telomere shortening and are associated with familial IPF. RTEL1 is a helicase; PARN is involved in TERC RNA processing. |

| DKC1, ZCCHC8, NAF1 [46,47] | Rare | Telomerase biogenesis | Mutations in these genes, which are essential for the assembly and function of telomerase, have been identified in IPF. |

| TINF2, ACD [48,49] | Rare | Telomere integrity (Shelterin complex) | Heterozygous mutations in these genes, which encode proteins that protect telomeres, have been documented in IPF. |

| Surfactant-Related Genes | |||

| SFTPA1, SFTPA2 [50,51,52,53,54,55] | Rare | Surfactant protein A production and function | Mutations (e.g., F198S, G231V in SFTPA2) are located in the carbohydrate recognition domain, leading to misfolded proteins, ER stress, and apoptosis in alveolar epithelial cells. Associated with early-onset fibrosis and lung cancer risk. |

| SFTPC [56,57,58,59] | Rare | Surfactant protein C production and function | Mutations, often in the BRICHOS domain, cause misfolded SP-C to accumulate in the ER, inducing ER stress. Predisposes to a wide range of fibrotic lung diseases. |

| SFTPB | Rare | Surfactant protein B production and function | Pathogenic variants have been associated with IPF. |

| ABCA3 [60,61,62] | Rare | Surfactant lipid transport | Mutations impair the function of this transporter in lamellar bodies, disrupting surfactant synthesis and metabolism and contributing to epithelial cell injury. |

| NKX2.1 [60] | Rare | Lung development; surfactant protein transcription | Pathogenic variants have been associated with IPF. |

| Biomarker | Type | Source | Clinical Applicability and Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| KL-6 (MUC1) | Mucin-type glycoprotein (epithelial injury marker) | Serum/plasma; BALF (research) | Aids differential diagnosis among ILDs; higher levels associate with disease extent, progression, acute exacerbations, and mortality; and they are useful for longitudinal monitoring (widely used in Japan). |

| Surfactant Protein D (SP-D) | Surfactant-associated collectin | Serum/plasma; BALF (research) | Reflects alveolar epithelial injury; elevated in IPF; predicts FVC decline and mortality; and useful for disease monitoring. |

| Surfactant Protein A (SP-A) | Surfactant-associated collectin | Serum/plasma; BALF (research) | Elevated in IPF; supports diagnosis/monitoring; prognostic value generally weaker than SP-D. |

| MMP-7 | Matrix metalloproteinase (ECM remodeling) | Serum/plasma | One of the most consistently validated prognostic biomarkers; predicts progression and mortality; correlates with HRCT fibrosis extent and FVC decline; and often used in multi-marker panels. |

| MMP-1 | Matrix metalloproteinase | Serum/plasma | Elevated in IPF; associated with disease activity and fibrosis remodeling, though its prognostic value is less robust than MMP-7. |

| CCL18 (PARC) | Chemokine (macrophage-derived) | Serum/plasma | Higher baseline concentrations predict mortality and acute exacerbations; tracks disease activity; independent prognostic signal in several cohorts. |

| YKL-40 (CHI3L1) | Chitinase-like glycoprotein | Serum/plasma | Associated with fibrosis burden, decline in lung function, and mortality; reflects epithelial injury/repair and macrophage activation. |

| Periostin (POSTN) | Matricellular ECM protein | Serum/plasma; lung tissue | Elevated in progressive IPF; associated with fibrogenic activity and worse outcomes; and potential tool for risk stratification and treatment monitoring. |

| Osteopontin (SPP1) | Cytokine/matricellular protein | Serum/BALF; lung tissue | Upregulated in IPF; correlates with disease severity and progression; and pathway target under investigation. |

| LOXL2 | ECM cross-linking enzyme | Serum; lung tissue | Marker of active matrix remodeling; higher levels associated with severity and progression; and therapeutic targeting to date has not improved outcomes (utility mainly as disease activity marker). |

| MUC5B promoter variant (rs35705950) | Genetic risk variant | Germline DNA (blood/saliva) | Strongest common genetic risk factor for IPF; paradoxically linked to better survival; and useful for risk stratification and research, not diagnostic alone. |

| Telomere-related genes (TERT, TERC, PARN, RTEL1) | Genetic variants (telomere maintenance) | Germline DNA; leukocyte telomere length | Mutations and short telomeres are associated with familial/sporadic IPF, earlier onset, worse outcomes, and transplant complications; they inform counseling and management. |

| Leukocyte telomere length | Genomic/aging biomarker | Peripheral blood leukocytes | Shorter telomeres predict faster progression, poorer survival, and toxicity risk with some therapies; complements genetic testing. |

| Circulating fibrocytes | Cellular biomarker (CD45+Col1+) | Peripheral blood | Elevated percentages predict worse survival and severe disease; potential marker of fibrogenic activity (research/selected centers). |

| ECM neo-epitopes (e.g., PRO-C3, PRO-C6; C1M/C3M) | Collagen turnover fragments | Serum | Reflect active fibrogenesis and ECM turnover; associate with progression and mortality; and promising for treatment monitoring. |

| microRNAs (e.g., miR-21, let-7d, miR-29) | Non-coding RNAs (regulatory) | Plasma/serum; lung tissue | Dysregulated in IPF; linked to fibrotic pathways and outcomes; and emerging prognostic/theranostic markers (research stage). |

| TGF-β1 | Cytokine (profibrotic) | Serum/BALF; tissue | Central to fibrosis biology; elevated but nonspecific; limited standalone clinical utility; and useful in mechanistic and pharmacodynamic studies. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Senhaji, L.; Senhaji, N.; Abbassi, M.; Karhate, M.; Serraj, M.; El Biaze, M.; Benjelloun, M.C.; Ouldim, K.; Bouguenouch, L.; Amara, B. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Comprehensive Review of Risk Factors, Genetics, Diagnosis, and Therapeutic Approaches. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010090

Senhaji L, Senhaji N, Abbassi M, Karhate M, Serraj M, El Biaze M, Benjelloun MC, Ouldim K, Bouguenouch L, Amara B. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Comprehensive Review of Risk Factors, Genetics, Diagnosis, and Therapeutic Approaches. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):90. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010090

Chicago/Turabian StyleSenhaji, Lamiyae, Nadia Senhaji, Marieme Abbassi, Meryem Karhate, Mounia Serraj, Mohammed El Biaze, Mohamed Chakib Benjelloun, Karim Ouldim, Laila Bouguenouch, and Bouchra Amara. 2026. "Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Comprehensive Review of Risk Factors, Genetics, Diagnosis, and Therapeutic Approaches" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010090

APA StyleSenhaji, L., Senhaji, N., Abbassi, M., Karhate, M., Serraj, M., El Biaze, M., Benjelloun, M. C., Ouldim, K., Bouguenouch, L., & Amara, B. (2026). Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Comprehensive Review of Risk Factors, Genetics, Diagnosis, and Therapeutic Approaches. Biomedicines, 14(1), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010090