Coenzyme A in Brain Biology and Neurodegeneration

Abstract

1. Introduction

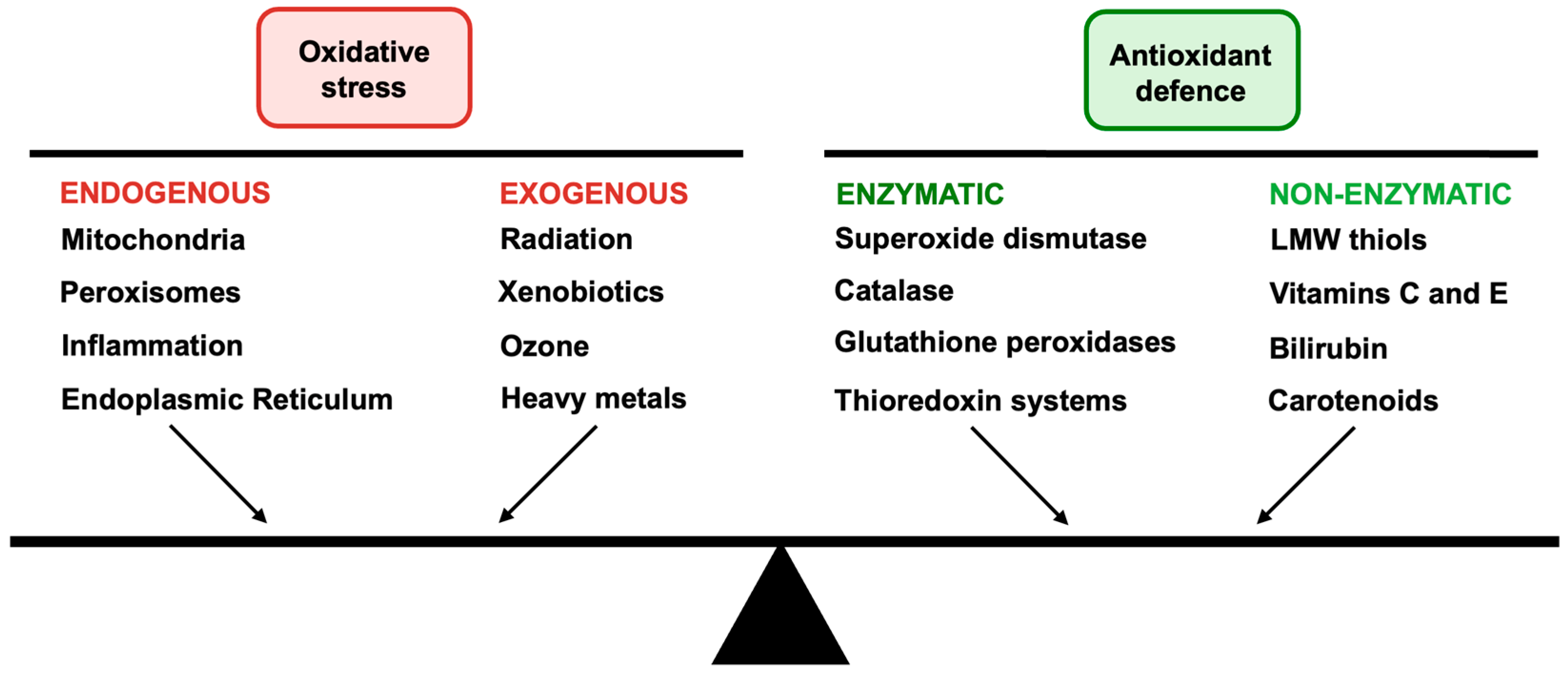

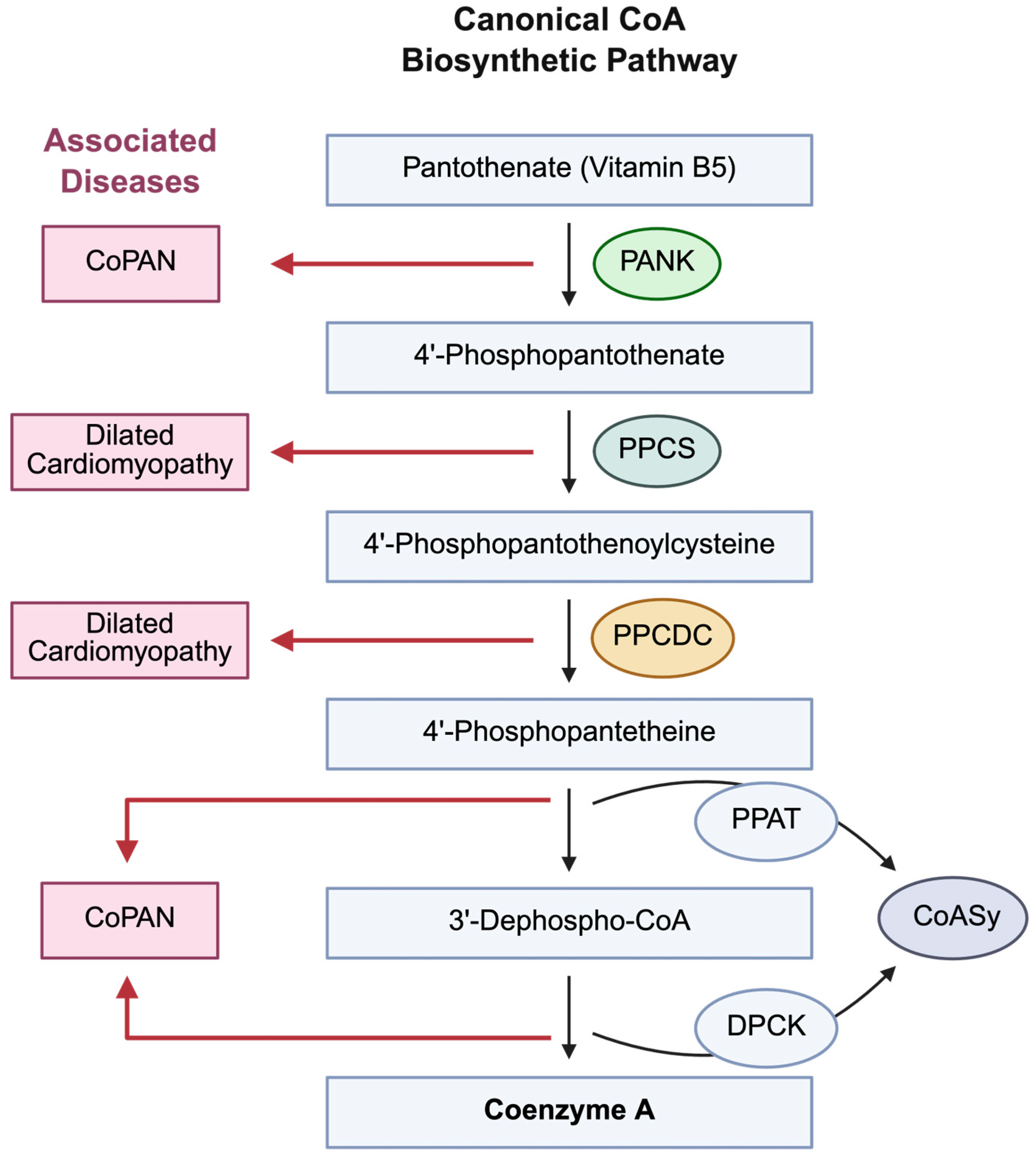

2. CoA in Brain Metabolism

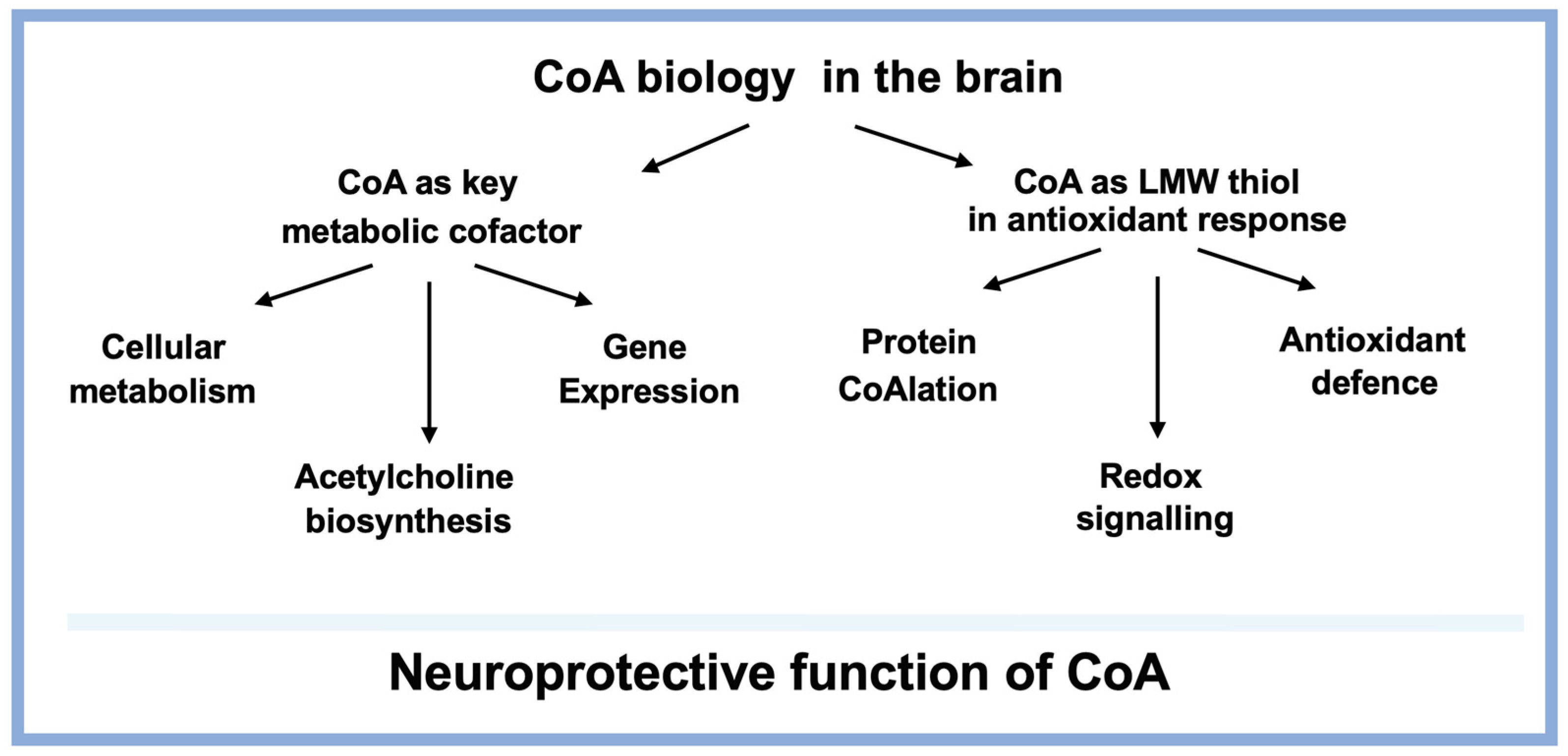

3. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Defence in Neuronal System

4. Antioxidant Functions of CoA in the Brain

5. Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CoA | Coenzyme A |

| PANK2 | Pantothenate Kinase 2 |

| CoASy | CoA Synthase |

| NBIA | Neurodegeneration with Brain Iron Accumulation |

| ETC | Electron Transport Chain |

| AD | Alzheimer’s Disease |

| ChAT | Choline Acetyltransferase |

| ACSS2 | Acetyl-CoA Synthetase |

| BHB | β-Hydroxybutyrate |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RNS | Reactive Nitrogen Species |

| VMAT2 | Vesicular Monoamine Transporter 2 |

| PD | Parkinson’s Disease |

| Aβ | Amyloid Beta |

| PUFAs | Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| Cat | Catalase |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| GSSG | Glutathione Disulfide |

| Trx | Thioredoxin |

| Prx | Peroxiredoxin |

| LMW | Low Molecular Weight |

| MS | Mass Spectrometry |

| TXNRD2 | Thioredoxin Reductase 2 |

| PPAT | Phospho-panthethine transferase |

| DPCK | Dephospho CoA kinase |

| CoADR | CoA Disulfide Reductase |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| IF | Immunofluorescence |

| NFT | Neurofibrillary Tangle |

| PKAN | Pantothenate Kinase-Associated Neurodegeneration |

| iPSc | induced Pluripotent Stem Cells |

References

- Sokoloff, L. The metabolism of the central nervous system in vivo. In Handbook of Physiology-Neurophysiology; Field, J.J., Magoun, H.W., Hall, V.E., Eds.; American Physiological Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1960; Volume 3, pp. 1843–1860. [Google Scholar]

- Hyder, F.; Rothman, D.L.; Bennett, M.R. Cortical energy demands of signaling and nonsignaling components in brain are conserved across mammalian species and activity levels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 3549–3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.J.; Jolivet, R.; Attwell, D. Synaptic energy use and supply. Neuron 2012, 75, 762–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.H.; Qiao, H.; Du, F.; Xiong, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Ugurbil, K.; Chen, W. Quantitative imaging of energy expenditure in human brain. Neuroimage 2012, 60, 2107–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, N.J.; Wodschow, H.Z.; Nilsson, M.; Rungby, J. Effects of Ketone Bodies on Brain Metabolism and Function in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonardi, R.; Zhang, Y.M.; Rock, C.O.; Jackowski, S. Coenzyme A: Back in action. Prog. Lipid Res. 2005, 44, 125–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakovic, J.; Lopez Martinez, D.; Nikolaou, S.; Yu, B.Y.K.; Tossounian, M.A.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Thrasivoulou, C.; Filonenko, V.; Gout, I. Regulation of the CoA Biosynthetic Complex Assembly in Mammalian Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tossounian, M.A.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, B.Y.K.; Markey, S.A.; Malanchuk, O.; Zhu, Y.; Cain, A.; Gout, I. Low-molecular-weight thiol transferases in redox regulation and antioxidant defence. Redox Biol. 2024, 71, 103094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filonenko, V.; Gout, I. Discovery and functional characterisation of protein CoAlation and the antioxidant function of coenzyme A. BBA Adv. 2023, 3, 100075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gout, I. Coenzyme A, protein CoAlation and redox regulation in mammalian cells. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2018, 46, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoulou, F.L.; Sibon, O.C.; Jackowski, S.; Gout, I. Coenzyme A and its derivatives: Renaissance of a textbook classic. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2014, 42, 1025–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, C.; Gout, I. The two faces of coenzyme A in cellular biology. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 233, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, Y.; Zhyvoloup, A.; Bakovic, J.; Thomas, N.; Yu, B.Y.K.; Das, S.; Orengo, C.; Newell, C.; Ward, J.; Saladino, G.; et al. Protein CoAlation and antioxidant function of coenzyme A in prokaryotic cells. Biochem. J. 2018, 475, 1909–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuchiya, Y.; Peak-Chew, S.Y.; Newell, C.; Miller-Aidoo, S.; Mangal, S.; Zhyvoloup, A.; Bakovic, J.; Malanchuk, O.; Pereira, G.C.; Kotiadis, V.; et al. Protein CoAlation: A redox-regulated protein modification by coenzyme A in mammalian cells. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 2489–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakovic, J.; Yu, B.Y.K.; Silva, D.; Baczynska, M.; Peak-Chew, S.Y.; Switzer, A.; Burchell, L.; Wigneshweraraj, S.; Vandanashree, M.; Gopal, B.; et al. Redox Regulation of the Quorum-sensing Transcription Factor AgrA by Coenzyme A. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellany, F.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Tran, T.M.; Chan, A.W.E.; Allan, H.; Gout, I.; Tabor, A.B. Design and synthesis of Coenzyme A analogues as Aurora kinase A inhibitors: An exploration of the roles of the pyrophosphate and pantetheine moieties. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2020, 28, 115740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakovic, J.; Yu, B.Y.K.; Silva, D.; Chew, S.P.; Kim, S.; Ahn, S.H.; Palmer, L.; Aloum, L.; Stanzani, G.; Malanchuk, O.; et al. A key metabolic integrator, coenzyme A, modulates the activity of peroxiredoxin 5 via covalent modification. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 461, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Westaway, S.K.; Levinson, B.; Johnson, M.A.; Gitschier, J.; Hayflick, S.J. A novel pantothenate kinase gene (PANK2) is defective in Hallervorden-Spatz syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2001, 28, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusi, S.; Valletta, L.; Haack, T.B.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Venco, P.; Pasqualato, S.; Goffrini, P.; Tigano, M.; Demchenko, N.; Wieland, T.; et al. Exome sequence reveals mutations in CoA synthase as a cause of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2014, 94, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.M., 3rd; Cookson, M.R.; Van Den Bosch, L.; Zetterberg, H.; Holtzman, D.M.; Dewachter, I. Hallmarks of neurodegenerative diseases. Cell 2023, 186, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashley, T.; Tossounian, M.A.; Costello Heaven, N.; Wallworth, S.; Peak-Chew, S.; Bradshaw, A.; Cooper, J.M.; de Silva, R.; Srai, S.K.; Malanchuk, O.; et al. Extensive Anti-CoA Immunostaining in Alzheimer’s Disease and Covalent Modification of Tau by a Key Cellular Metabolite Coenzyme A. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 739425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzig, S.; Raemy, E.; Montessuit, S.; Veuthey, J.L.; Zamboni, N.; Westermann, B.; Kunji, E.R.; Martinou, J.C. Identification and functional expression of the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier. Science 2012, 337, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, J.C.; Jitrapakdee, S.; Chapman-Smith, A. Pyruvate carboxylase. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1998, 30, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowska-Kulawy, A.; Klimaszewska-Lata, J.; Gul-Hinc, S.; Ronowska, A.; Szutowicz, A. Metabolic and Cellular Compartments of Acetyl-CoA in the Healthy and Diseased Brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindasamy, L.; Pedersen, B.; Lian, W.; Kukar, T.; Gu, Y.; Jin, S.; Agbandje-McKenna, M.; Wu, D.; McKenna, R. Structural insights and functional implications of choline acetyltransferase. J. Struct. Biol. 2004, 148, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strada, O.; Vyas, S.; Hirsch, E.C.; Ruberg, M.; Brice, A.; Agid, Y.; Javoy-Agid, F. Decreased choline acetyltransferase mRNA expression in the nucleus basalis of Meynert in Alzheimer disease: An in situ hybridization study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 9549–9553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mews, P.; Donahue, G.; Drake, A.M.; Luczak, V.; Abel, T.; Berger, S.L. Acetyl-CoA synthetase regulates histone acetylation and hippocampal memory. Nature 2017, 546, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Lin, A.; Cai, L.; Huang, W.; Yan, S.; Wei, Y.; Ruan, X.; Fang, W.; Dai, X.; Cheng, J.; et al. ACSS2-dependent histone acetylation improves cognition in mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2023, 18, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poitelon, Y.; Kopec, A.M.; Belin, S. Myelin Fat Facts: An Overview of Lipids and Fatty Acid Metabolism. Cells 2020, 9, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, M.C.W.; Garnham, N.; Sweeney, S.T.; Landgraf, M. Regulation of neuronal development and function by ROS. FEBS Lett. 2018, 592, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogan, N.; Cabot, J.B. Light and electron microscopic analyses of intraspinal axon collaterals of sympathetic preganglionic neurons. Brain Res. 1991, 541, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Z.H.; Cai, Q. Mitochondrial transport in neurons: Impact on synaptic homeostasis and neurodegeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, R.Z.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Z.B. Mitochondrial electron transport chain, ROS generation and uncoupling (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 44, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, A.; de Oliveira, J.; da Silva Pontes, L.V.; de Souza Junior, J.F.; Goncalves, T.A.F.; Dantas, S.H.; de Almeida Feitosa, M.S.; Silva, A.O.; de Medeiros, I.A. ROS: Basic Concepts, Sources, Cellular Signaling, and its Implications in Aging Pathways. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 1225578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada Sanchez, A.M.; Mejia-Toiber, J.; Massieu, L. Excitotoxic neuronal death and the pathogenesis of Huntington’s disease. Arch. Med. Res. 2008, 39, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olajide, O.J.; Gbadamosi, I.T.; Yawson, E.O.; Arogundade, T.; Lewu, F.S.; Ogunrinola, K.Y.; Adigun, O.O.; Bamisi, O.; Lambe, E.; Arietarhire, L.O.; et al. Hippocampal Degeneration and Behavioral Impairment During Alzheimer-Like Pathogenesis Involves Glutamate Excitotoxicity. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 71, 1205–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafon-Cazal, M.; Pietri, S.; Culcasi, M.; Bockaert, J. NMDA-dependent superoxide production and neurotoxicity. Nature 1993, 364, 535–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudle, W.M.; Richardson, J.R.; Wang, M.Z.; Taylor, T.N.; Guillot, T.S.; McCormack, A.L.; Colebrooke, R.E.; Di Monte, D.A.; Emson, P.C.; Miller, G.W. Reduced vesicular storage of dopamine causes progressive nigrostriatal neurodegeneration. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 8138–8148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamagno, E.; Bardini, P.; Obbili, A.; Vitali, A.; Borghi, R.; Zaccheo, D.; Pronzato, M.A.; Danni, O.; Smith, M.A.; Perry, G.; et al. Oxidative stress increases expression and activity of BACE in NT2 neurons. Neurobiol. Dis. 2002, 10, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opazo, C.; Huang, X.; Cherny, R.A.; Moir, R.D.; Roher, A.E.; White, A.R.; Cappai, R.; Masters, C.L.; Tanzi, R.E.; Inestrosa, N.C.; et al. Metalloenzyme-like activity of Alzheimer’s disease beta-amyloid. Cu-dependent catalytic conversion of dopamine, cholesterol, and biological reducing agents to neurotoxic H2O2. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 40302–40308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuppusamy, P.; Zweier, J.L. Characterization of free radical generation by xanthine oxidase. Evidence for hydroxyl radical generation. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 9880–9884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Tabales, J.; Garcia-Martin, E.; Agundez, J.A.G.; Gutierrez-Merino, C. Modulation of CYP2C9 activity and hydrogen peroxide production by cytochrome b5. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, E.; Sevier, C.S.; Heldman, N.; Vitu, E.; Bentzur, M.; Kaiser, C.A.; Thorpe, C.; Fass, D. Generating disulfides enzymatically: Reaction products and electron acceptors of the endoplasmic reticulum thiol oxidase Ero1p. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babior, B.M. NADPH Oxidase: An Update. Blood 1999, 93, 1464–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, B.; Hemmens, B. Biosynthesis and action of nitric oxide in mammalian cells. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1997, 22, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doser, R.L.; Knight, K.M.; Deihl, E.W.; Hoerndli, F.J. Activity-dependent mitochondrial ROS signaling regulates recruitment of glutamate receptors to synapses. Elife 2024, 13, e92376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehm, R.; Baldensperger, T.; Raupbach, J.; Hohn, A. Protein oxidation—Formation mechanisms, detection and relevance as biomarkers in human diseases. Redox Biol. 2021, 42, 101901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringfellow, H.M.; Jones, M.R.; Green, M.C.; Wilson, A.K.; Francisco, J.S. Selectivity in ROS-induced peptide backbone bond cleavage. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 11399–11404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajieva, P.; Bayatti, N.; Granold, M.; Behl, C.; Moosmann, B. Membrane protein oxidation determines neuronal degeneration. J. Neurochem. 2015, 133, 352–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, G.L.; Yin, H.; Hardy, K.D.; Davies, S.S.; Roberts, L.J., 2nd. Isoprostane generation and function. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 5973–5996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratico, D.; Uryu, K.; Leight, S.; Trojanoswki, J.Q.; Lee, V.M. Increased lipid peroxidation precedes amyloid plaque formation in an animal model of Alzheimer amyloidosis. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 4183–4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, F.; Ma, X.; Perry, G.; Zhu, X. Mitochondria dysfunction in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: Recent advances. Mol. Neurodegener. 2020, 15, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valko, M.; Rhodes, C.J.; Moncol, J.; Izakovic, M.; Mazur, M. Free radicals, metals and antioxidants in oxidative stress-induced cancer. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2006, 160, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighodaro, O.M.; Akinloye, O.A. First line defence antioxidants-superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX): Their fundamental role in the entire antioxidant defence grid. Alex. J. Med. 2018, 54, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agar, N.S.; Sadrzadeh, S.M.; Hallaway, P.E.; Eaton, J.W. Erythrocyte catalase. A somatic oxidant defense? J. Clin. Investig. 1986, 77, 319–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berdynski, M.; Miszta, P.; Safranow, K.; Andersen, P.M.; Morita, M.; Filipek, S.; Zekanowski, C.; Kuzma-Kozakiewicz, M. SOD1 mutations associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis analysis of variant severity. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, C.; Olinescu, R.; Reid, K.G.; O’Brien, P.J. Properties and regulation of glutathione peroxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 1970, 245, 3632–3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Yu, W.; Liu, J.; Tang, D.; Yang, L.; Chen, X. Oxidative cell death in cancer: Mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aust, S.D.; Morehouse, L.A.; Thomas, C.E. Role of metals in oxygen radical reactions. J. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1985, 1, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, B. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant vitamins: Mechanisms of action. Am. J. Med. 1994, 97, 5S–13S; discussion 22S–28S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, S.; Li, L.; Weeber, E.J.; May, J.M. Ascorbate transport by primary cultured neurons and its role in neuronal function and protection against excitotoxicity. J. Neurosci. Res. 2007, 85, 1046–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, A.; Gautam, R.; Chatterjee, S.; Ariese, F.; Sikdar, S.K.; Umapathy, S. Ascorbate protects neurons against oxidative stress: A Raman microspectroscopic study. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2015, 6, 1794–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doba, T.; Burton, G.W.; Ingold, K.U. Antioxidant and co-antioxidant activity of vitamin C. The effect of vitamin C, either alone or in the presence of vitamin E or a water-soluble vitamin E analogue, upon the peroxidation of aqueous multilamellar phospholipid liposomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1985, 835, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niki, E. Role of vitamin E as a lipid-soluble peroxyl radical scavenger: In vitro and in vivo evidence. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 66, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Boiti, A.; Vallone, D.; Foulkes, N.S. Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling and Oxidative Stress: Transcriptional Regulation and Evolution. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malanchuk, O.M.; Panasyuk, G.G.; Serbyn, N.M.; Gout, I.T.; Filonenko, V.V. Generation and characterization of monoclonal antibodies specific to Coenzyme A. Biopolym. Cell 2015, 31, 187–192. [Google Scholar]

- Aloum, L.; Brimson, C.A.; Zhyvoloup, A.; Baines, R.; Bakovic, J.; Filonenko, V.; Thompson, C.R.L.; Gout, I. Coenzyme A and protein CoAlation levels are regulated in response to oxidative stress and during morphogenesis in Dictyostelium discoideum. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 511, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, Y.; Byrne, D.P.; Burgess, S.G.; Bormann, J.; Bakovic, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhyvoloup, A.; Yu, B.Y.K.; Peak-Chew, S.; Tran, T.; et al. Covalent Aurora A regulation by the metabolic integrator coenzyme A. Redox Biol. 2020, 28, 101318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, B.Y.K.; Tossounian, M.A.; Hristov, S.D.; Lawrence, R.; Arora, P.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Peak-Chew, S.Y.; Filonenko, V.; Oxenford, S.; Angell, R.; et al. Regulation of metastasis suppressor NME1 by a key metabolic cofactor coenzyme A. Redox Biol. 2021, 44, 101978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, J.T.; Lin, C.C.; Lin, Y.T.; Chen, S.Y.; Setayeshpour, Y.; Chen, Y.; Dunn, D.; Soderblom, E.; Zhang, G.F.; Filonenko, V.; et al. Coenzyme A protects against ferroptosis via CoAlation of thioredoxin reductase 2. Res. Sq. 2024, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- delCardayre, S.B.; Davies, J.E. Staphylococcus aureus coenzyme A disulfide reductase, a new subfamily of pyridine nucleotide-disulfide oxidoreductase. Sequence, expression, and analysis of cdr. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 5752–5757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olzhausen, J.; Schubbe, S.; Schuller, H.J. Genetic analysis of coenzyme A biosynthesis in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Identification of a conditional mutation in the pantothenate kinase gene CAB1. Curr. Genet. 2009, 55, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizioli, D.; Tiso, N.; Guglielmi, A.; Saraceno, C.; Busolin, G.; Giuliani, R.; Khatri, D.; Monti, E.; Borsani, G.; Argenton, F.; et al. Knock-down of pantothenate kinase 2 severely affects the development of the nervous and vascular system in zebrafish, providing new insights into PKAN disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2016, 85, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatri, D.; Zizioli, D.; Tiso, N.; Facchinello, N.; Vezzoli, S.; Gianoncelli, A.; Memo, M.; Monti, E.; Borsani, G.; Finazzi, D. Down-regulation of coasy, the gene associated with NBIA-VI, reduces Bmp signaling, perturbs dorso-ventral patterning and alters neuronal development in zebrafish. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrechts, R.A.; Schepers, H.; Yu, Y.; van der Zwaag, M.; Autio, K.J.; Vieira-Lara, M.A.; Bakker, B.M.; Tijssen, M.A.; Hayflick, S.J.; Grzeschik, N.A.; et al. CoA-dependent activation of mitochondrial acyl carrier protein links four neurodegenerative diseases. EMBO Mol. Med. 2019, 11, e10488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosveld, F.; Rana, A.; van der Wouden, P.E.; Lemstra, W.; Ritsema, M.; Kampinga, H.H.; Sibon, O.C. De novo CoA biosynthesis is required to maintain DNA integrity during development of the Drosophila nervous system. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008, 17, 2058–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, Y.M.; Duncan, J.L.; Westaway, S.K.; Yang, H.; Nune, G.; Xu, E.Y.; Hayflick, S.J.; Gitschier, J. Deficiency of pantothenate kinase 2 (Pank2) in mice leads to retinal degeneration and azoospermia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 14, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, D.; Dusi, S.; Morbin, M.; Uggetti, A.; Moda, F.; D’Amato, I.; Giordano, C.; d’Amati, G.; Cozzi, A.; Levi, S.; et al. Pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration: Altered mitochondria membrane potential and defective respiration in Pank2 knock-out mouse model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 5294–5305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, C.; Yao, J.; Frank, M.W.; Rock, C.O.; Jackowski, S. A pantothenate kinase-deficient mouse model reveals a gene expression program associated with brain coenzyme a reduction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Meo, I.; Cavestro, C.; Pedretti, S.; Fu, T.; Ligorio, S.; Manocchio, A.; Lavermicocca, L.; Santambrogio, P.; Ripamonti, M.; Levi, S.; et al. Neuronal Ablation of CoA Synthase Causes Motor Deficits, Iron Dyshomeostasis, and Mitochondrial Dysfunctions in a CoPAN Mouse Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.; Kureishy, N.; Church, S.J.; Scholefield, M.; Unwin, R.D.; Xu, J.; Patassini, S.; Cooper, G.J.S. Vitamin B5 (d-pantothenic acid) localizes in myelinated structures of the rat brain: Potential role for cerebral vitamin B5 stores in local myelin homeostasis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 522, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholefield, M.; Church, S.J.; Xu, J.; Patassini, S.; Cooper, G.J.S. Localized Pantothenic Acid (Vitamin B5) Reductions Present Throughout the Dementia with Lewy Bodies Brain. J. Park. Dis. 2024, 14, 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.K.; Subramanian, C.; Yun, M.K.; Frank, M.W.; White, S.W.; Rock, C.O.; Lee, R.E.; Jackowski, S. A therapeutic approach to pantothenate kinase associated neurodegeneration. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ma, H.; Jin, M.; Zhang, S.; Qu, S.; Wang, G.; Aa, J. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Evaluation of PZ-2891, an Anti-Alzheimer’s Disease Agonist of PANK2. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, C.; Frank, M.W.; Sukhun, R.; Henry, C.E.; Wade, A.; Harden, M.E.; Rao, S.; Tangallapally, R.; Yun, M.K.; White, S.W.; et al. Pantothenate Kinase Activation Restores Brain Coenzyme A in a Mouse Model of Pantothenate Kinase-Associated Neurodegeneration. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2024, 388, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BridgeBio Pharma Inc. Available online: https://bridgebio.com/news/bridgebio-pharma-presents-positive-phase-1-data-in-healthy-volunteers-advancing-development-of-bbp-671-for-pantothenate-kinase-associated-neurodegeneration-pkan-and-organic-acidemias/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Bais, S.; Rana, R.K.; Dongre, N.; Goyanar, G.; Panwar, A.S.; Soni, A.K.; Singune, S.L. Protective effect of pantothenic acid in kainic acid-induced status eilepticus and associated neurodegeneration in mice. Adv. Neurol. 2022, 1, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.Y.; Hogarth, P.; Placzek, A.; Gregory, A.M.; Fox, R.; Zhen, D.; Hamada, J.; van der Zwaag, M.; Lambrechts, R.; Jin, H.; et al. 4′-Phosphopantetheine corrects CoA, iron, and dopamine metabolic defects in mammalian models of PKAN. EMBO Mol. Med. 2019, 11, e10489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Gijsel-Bonnello, M.; Baranger, K.; Benech, P.; Rivera, S.; Khrestchatisky, M.; de Reggi, M.; Gharib, B. Metabolic changes and inflammation in cultured astrocytes from the 5xFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease: Alleviation by pantethine. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Cordoba, M.; Reche-Lopez, D.; Cilleros-Holgado, P.; Talaveron-Rey, M.; Villalon-Garcia, I.; Povea-Cabello, S.; Suarez-Rivero, J.M.; Suarez-Carrillo, A.; Munuera-Cabeza, M.; Pinero-Perez, R.; et al. Therapeutic approach with commercial supplements for pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration with residual PANK2 expression levels. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orellana, D.I.; Santambrogio, P.; Rubio, A.; Yekhlef, L.; Cancellieri, C.; Dusi, S.; Giannelli, S.G.; Venco, P.; Mazzara, P.G.; Cozzi, A.; et al. Coenzyme A corrects pathological defects in human neurons of PANK2-associated neurodegeneration. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016, 8, 1197–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, D.; Brett, C.; Cho, J.; Lashley, T.; Gout, I. Coenzyme A in Brain Biology and Neurodegeneration. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010069

Zhang D, Brett C, Cho J, Lashley T, Gout I. Coenzyme A in Brain Biology and Neurodegeneration. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010069

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Dejun, Charlie Brett, Jason Cho, Tammaryn Lashley, and Ivan Gout. 2026. "Coenzyme A in Brain Biology and Neurodegeneration" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010069

APA StyleZhang, D., Brett, C., Cho, J., Lashley, T., & Gout, I. (2026). Coenzyme A in Brain Biology and Neurodegeneration. Biomedicines, 14(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010069