Antioxidant and Neuroprotective Capacity of Resveratrol-Loaded Polymeric Micelles in In Vitro and In Vivo Models with Generated Oxidative Stress

Abstract

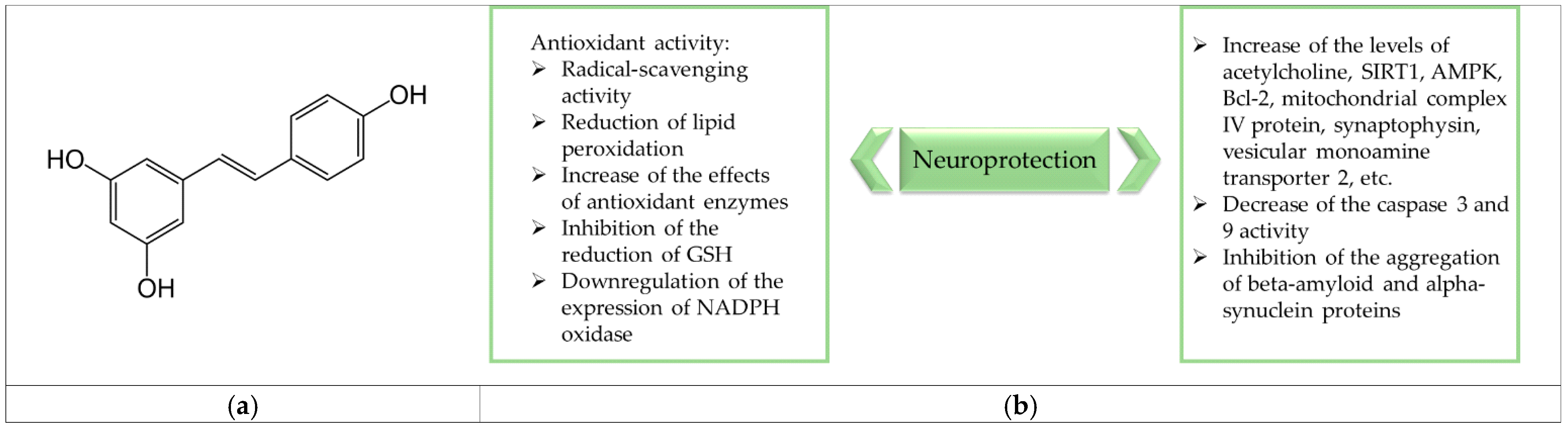

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Resveratrol-Loaded Micelles

2.3. In Vitro Antioxidant Activity

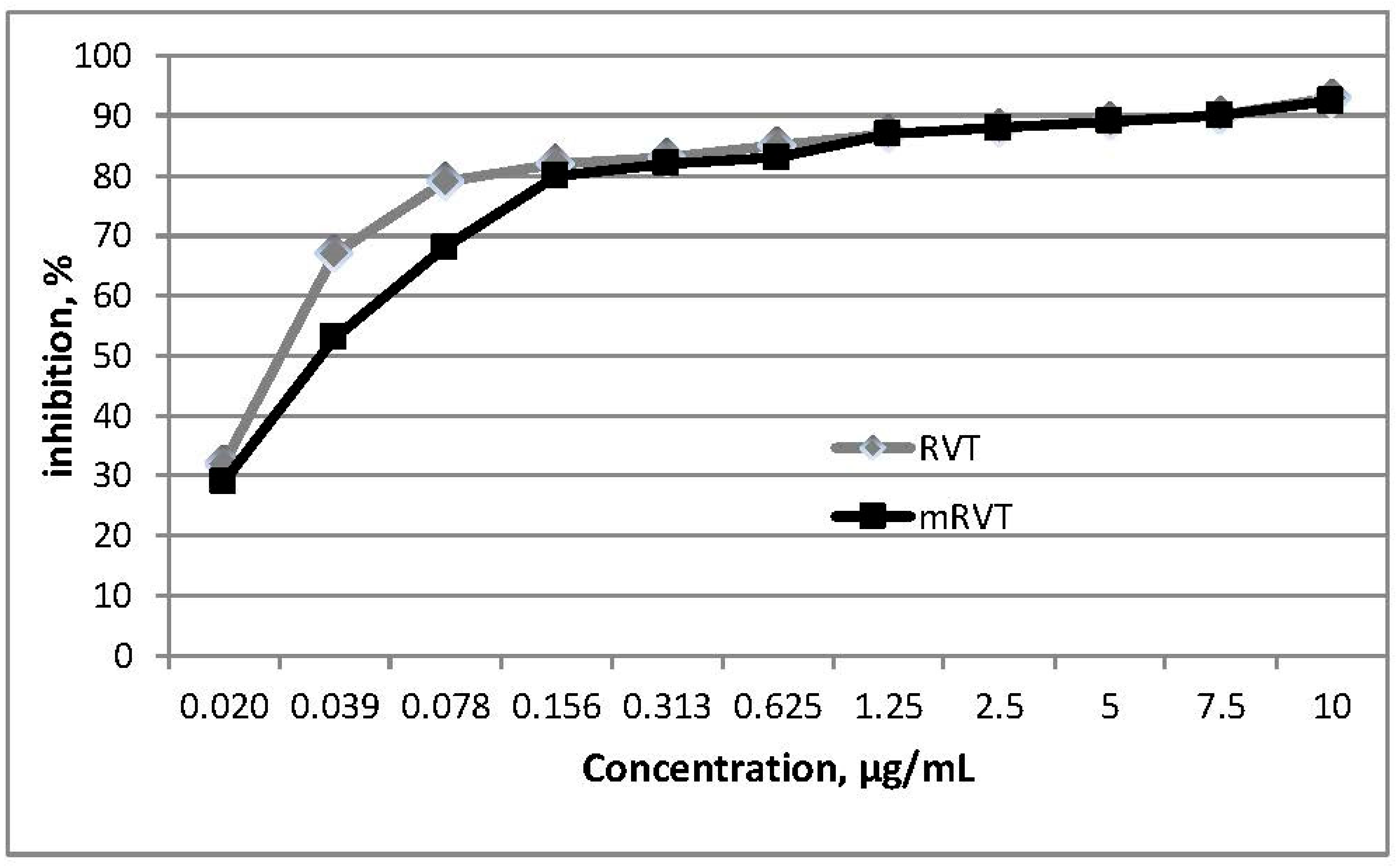

2.3.1. DPPH and ABTS Radical Scavenging Activity

2.3.2. Superoxide Anion Scavenging Assay (NBT)

2.3.3. Ferric-Reducing Power Assay (FRAP)

2.3.4. Copper-Reducing Power Assay (CUPRAC)

2.3.5. Iron-Induced Lipid Peroxidation (TBA-Test)

2.4. In Vivo Antioxidant Activity

2.4.1. Animals

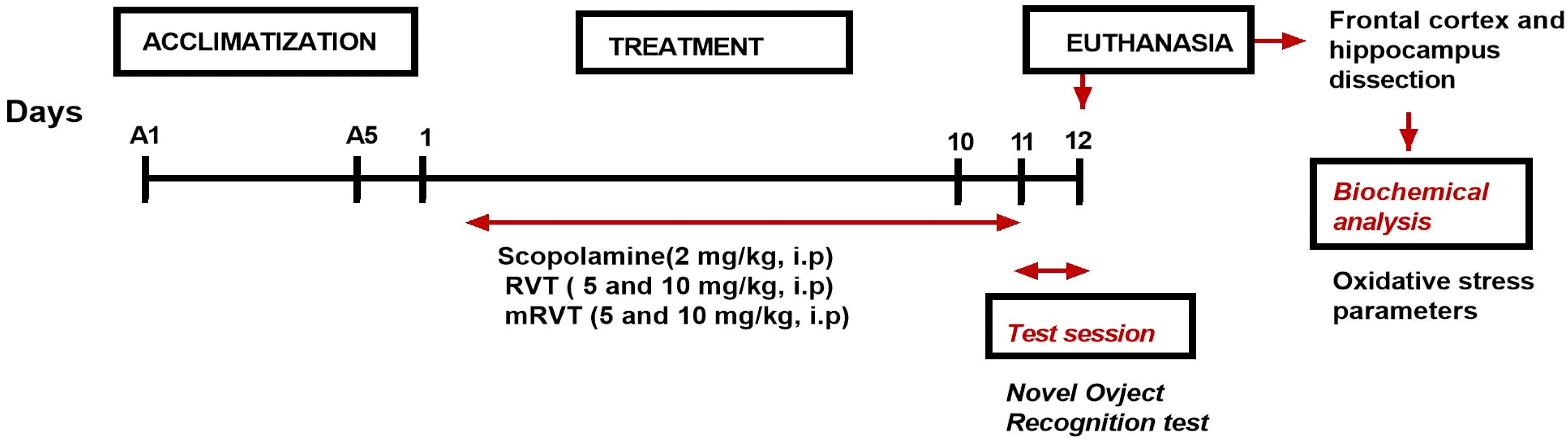

2.4.2. Experimental Design

- Control (0.9% NaCl, i.p);

- Sco (scopolamine 2 mg/kg, i.p);

- Sco + RVT 5 (5 mg/kg RVT, i.p);

- Sco + RVT 10 (10 mg/kg RVT, i.p);

- Sco + mRTV 5 (5 mg/kg RVT, i.p);

- Sco + mRTV 10 (10 mg/kg RVT, i.p).

2.4.3. Novel Object Recognition Test (NOR)

2.4.4. Tissue Preparation

2.4.5. Oxidative Stress Parameters

2.5. Neuroprotective Capacity

2.5.1. Synaptosomal Viability Assay

2.5.2. GSH Determination in Isolated Brain Synaptosomes

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

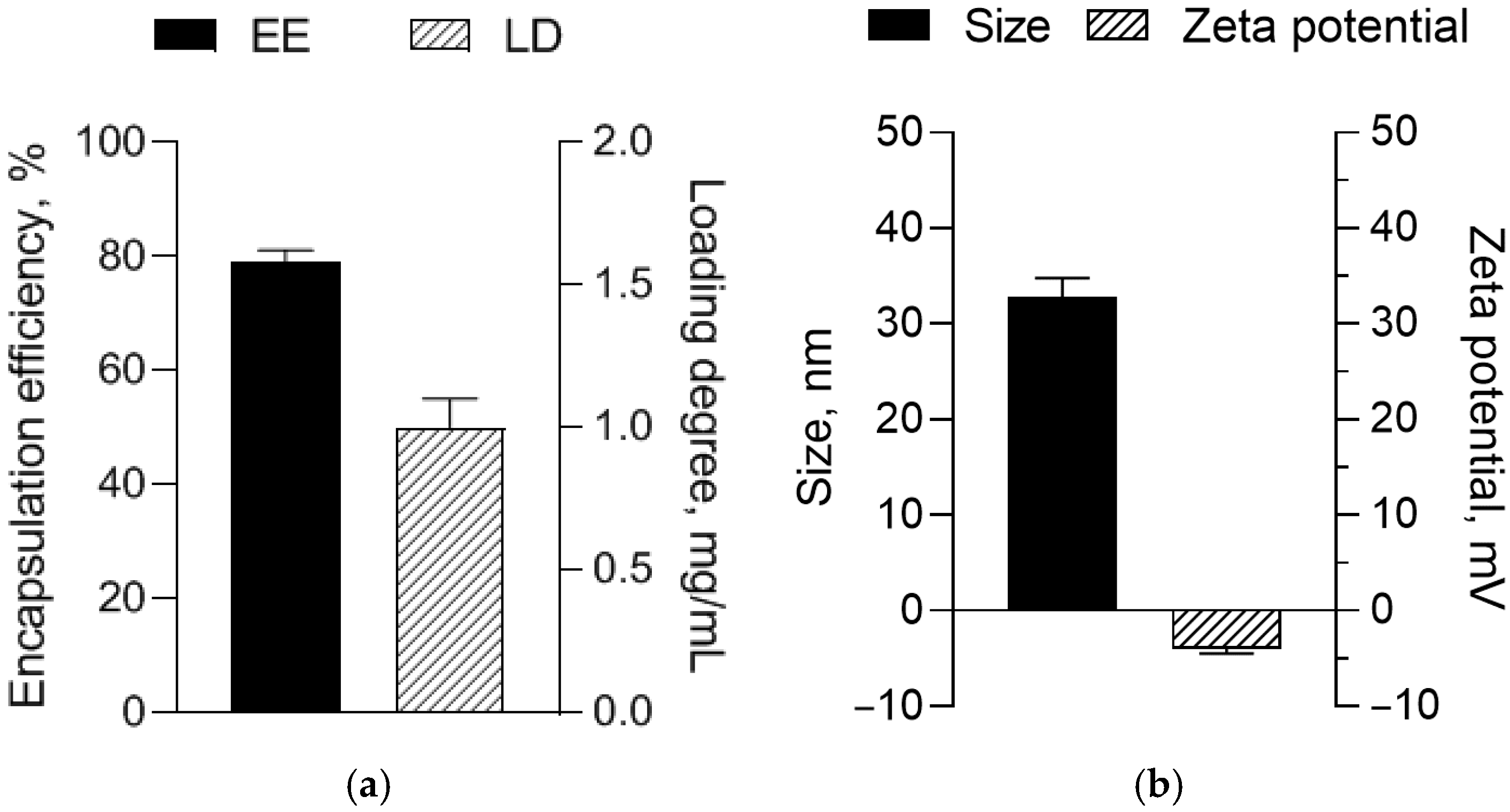

3.1. Characterization of Resveratrol-Loaded Micelles

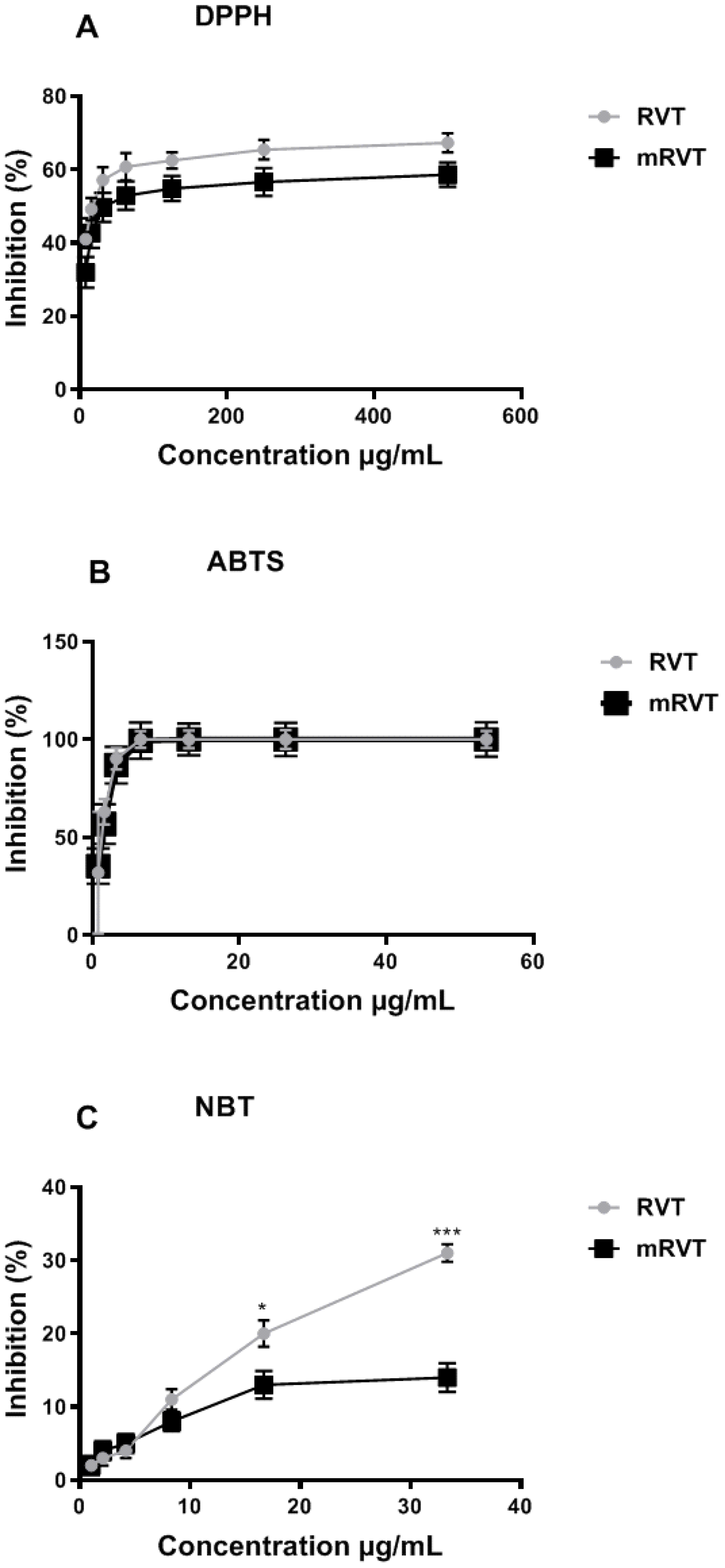

3.2. In Vitro Antioxidant Activity

3.3. In Vivo Antioxidant Activity

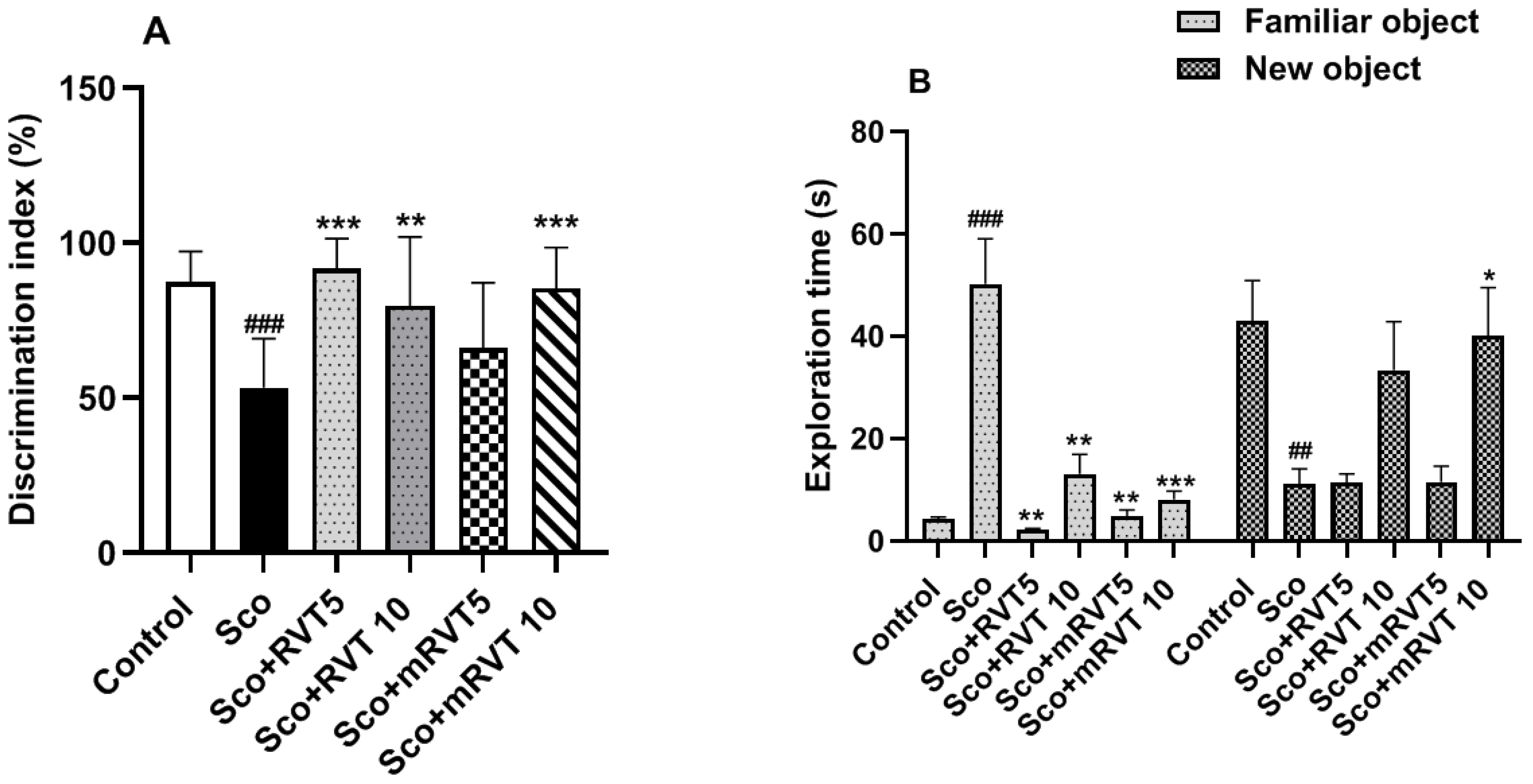

3.3.1. Effect of RVT and mRVT on Recognition Memory of Rats with Scopolamine-Induced Memory Impairment (Novel Object Recognition Test)

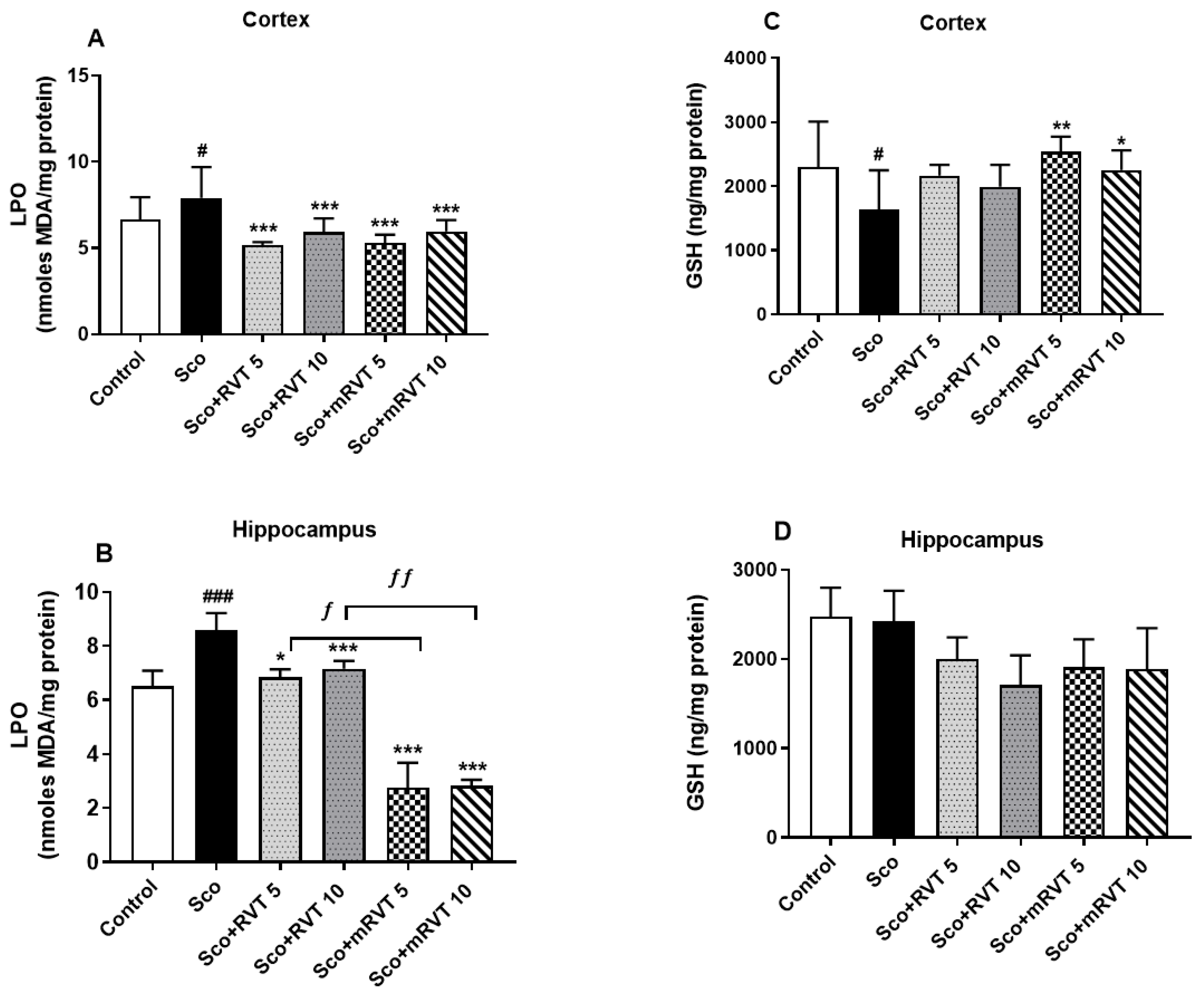

3.3.2. Effect of RVT and mRVT on LPO and GSH Levels in the Cortex and Hippocampus of Rats with Scopolamine-Induced Memory Impairment

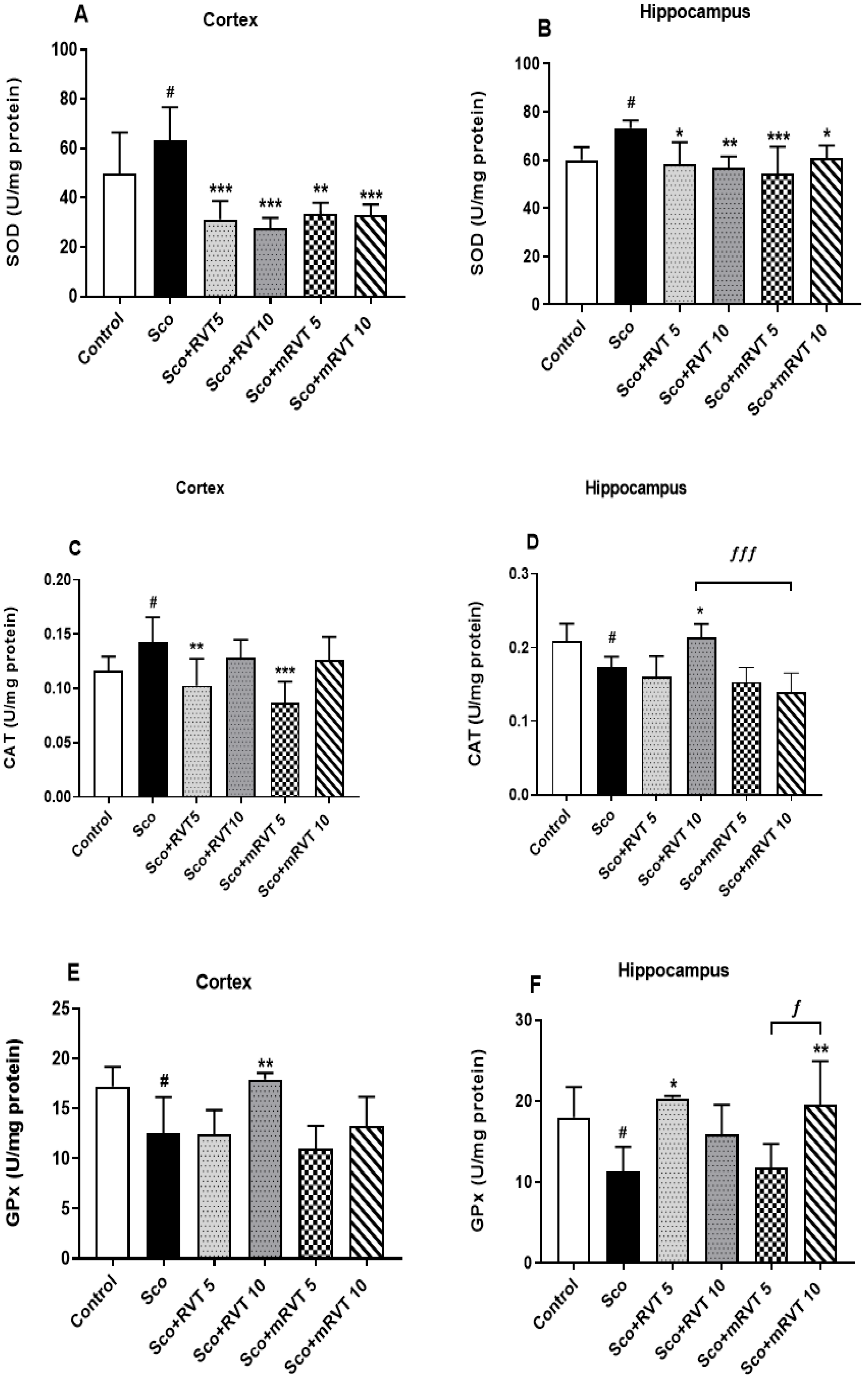

3.3.3. Effect of RVT and mRVT on SOD, CAT, and GPx Activity in the Cortex and Hippocampus of Rats with Scopolamine-Induced Memory Impairment

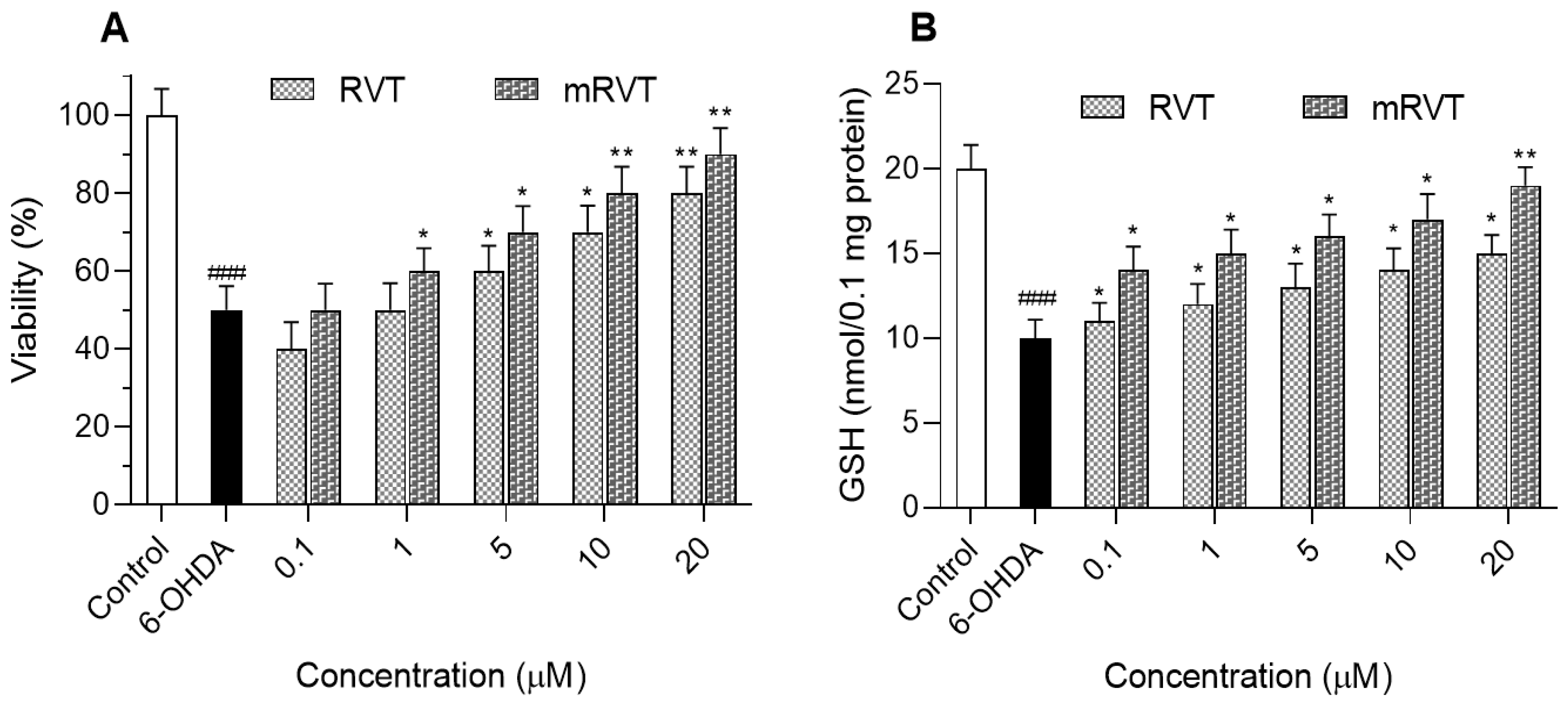

3.4. Neuroprotective Capacity in a Synaptosomal Model of Neurotoxicity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABTS | 2,2′-azino-bis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid |

| AChE | Acetylcholineesterase |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| CAT | Catalase |

| CUPPRAC | Cupric reducing antioxidant capacity |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| FRAP | Ferric reducing antioxidant power |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| IC50 | Half maximal inhibitory concentration |

| i.p. | Intraperitoneal |

| LPO | Lipid peroxidation |

| MDA | Malonedialdehyde |

| NADPH | Nicotine adenine dinucleotide phosphate hydrate |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RVT | Resveratrol |

| mRVT | Micellar resveratrol |

| OS | Oxidative stress |

| Sco | Scopolamine |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| TE | Trolox equivalent |

| TBA | Thiobarbituric acid |

| 6-OHDA | 6-hydroxydopamine hydrobromide |

References

- Rego, A.C.; Oliveira, C.R. Mitochondrial dysfunction and reactive oxygen species in excitotoxicity and apoptosis: Implications for the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Neurochem. Res. 2003, 28, 1563–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlief, M.L.; Gitlin, J.D. Copper homeostasis in the CNS: A novel link between the NMDA receptor and copper homeostasis in the hippocampus. Mol. Neurobiol. 2006, 33, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.P.; Sies, H. The Redox Code. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015, 23, 734–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Michaelis, E.K. Selective neuronal vulnerability to oxidative stress in the brain. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2010, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Cha, M.; Lee, B.H. Neuroprotective Effect of Antioxidants in the Brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dröge, W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol. Rev. 2002, 82, 47–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wuliji, O.; Li, W.; Jiang, Z.G.; Ghanbari, H.A. Oxidative Stress and Neurodegenerative Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 24438–24475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubczyk, K.; Dec, K.; Kałduńska, J.; Kawczuga, D.; Kochman, J.; Janda, K. Reactive oxygen species-sources, functions, oxidative damage. Pol. Merkur. Lek. 2020, 48, 124–127. [Google Scholar]

- Kamaljeet; Singh, S.; Gupta, G.D.; Aran, K.R. Emerging role of antioxidants in Alzheimer’s disease: Insight into physiological, pathological mechanisms and management. Pharm. Sci. Adv. 2024, 2, 100021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yuan, F.; Li, P.; Gu, J.; Han, J.; Ni, Z.; Liu, F. Resveratrol inhibits HeLa cell proliferation by regulating mitochondrial function. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 241, 113788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, G.; Liu, Q.; Gao, T.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, O.; Cao, C.; Mao, M.; Xiao, M.; Zhang, X.; et al. Resveratrol and FGF1 synergistically ameliorates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity via activation of SIRT1-NRF2 pathway. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, C.; Sciatti, E.; Favero, G.; Bonomini, F.; Vizzardi, E.; Rezzani, R. Essential hypertension and oxidative stress: Novel future perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, Y.; Amin, H.I.M.; Mishra, V.; Vyas, M.; Prabhakar, P.K.; Gupta, M.; Kanday, R.; Sudhakar, K.; Saini, S.; Hromić-Jahjefendić, A.; et al. Application of nanotechnology to herbal antioxidants as improved phytomedicine: An expanding horizon. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 153, 113413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorowska, D.; Radzik, T.; Kalenik, S.; Rodacka, A. Natural radiosensitizers in radiotherapy: Cancer treatment by combining ionizing radiation with resveratrol. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizard, G.; Latruffe, N.; Vervandier-Fasseur, D. Aza- and aza-stilbens: Bio-isosteric analogs of resveratrol. Molecules 2020, 25, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borys, F.; Tobiasz, P.; Poterała, M.; Fabczak, H.; Krawczyk, H.; Joachimiak, E. Systematic studies on anti-cancer evaluation of stilbene and dibenzo[b,f]oxepine derivatives. Molecules 2023, 28, 3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannu, N.; Bhatnagar, A. Resveratrol: From enhanced biosynthesis and bioavailability to multitargeting chronic diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 2237–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbadua, O.G.; Kúsz, N.; Berkecz, R.; G’ati, T.; T’oth, G.; Hunyadi, A. Oxidized resveratrol metabolites as potent antioxidants and xanthine oxidase inhibitors. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, C.; Wang, Z.; Liu, W.; Pu, L.; Li, R.; Ai, C.; Xu, H.; Zhang, B.; Wang, T.; Zhang, X.; et al. Resveratrol ameliorates high altitude hypoxia-induced osteoporosis by suppressing the ROS/HIF signaling pathway. Molecules 2022, 27, 5538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramatyka, M. The radioprotective activity of resveratrol–metabolomic point of view. Metabolites 2022, 12, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.; Zhang, Z.; Han, X.; Yang, F.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, H. Systematic insight of resveratrol activated SIRT1 interactome through proximity labeling strategy. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, S.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Hu, X.; Shao, Y.; Wang, G.; Mao, D.; Li, C.; Chen, B.; Chen, X. The role of resveratrol on rheumatoid arthritis: From bench to bedside. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 829677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, M.C.; Nicol, C.J.B.; Lo, S.S.; Hung, S.W.; Wang, C.J.; Lin, C.H. Resveratrol mitigates oxygen and glucose deprivation-induced inflammation, NLRP3 inflammasome, and oxidative stress in 3D neuronal culture. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auti, A.; Alessio, N.; Ballini, A.; Dioguardi, M.; Cantore, S.; Scacco, S.; Vitiello, A.; Quagliuolo, L.; Rinaldi, B.; Santacroce, L.; et al. Protective effect of resveratrol against hypoxia-induced neural oxidative stress. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, I.M.; Subramanian, U.; Thirupathi, P.; Venkidasamy, B.; Samynathan, R.; Gangadhar, B.H.; Rajakumar, G.; Thiruvengadam, M. Resveratrol nanoparticles: A promising therapeutic advancement over native resveratrol. Processes 2020, 8, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Liu, J. Resveratrol: A review of plant sources, synthesis, stability, modification and food application. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 1392–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athar, M.; Back, J.H.; Tang, X.; Kim, A. Resveratrol: A reviewof preclinical studies for human cancer prevention. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2007, 224, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szende, B.; Tyihбk, E.; Kirбly-Vйghely, Z. Dose-dependent effect of resveratrol on proliferation and apoptosis in endothelialand tumor cell cultures. Exp. Mol. Med. 2000, 32, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotomatsu, A.; Nakano, M.; Hirai, S. Phospholipid peroxidation induced by the catechol-Fe3+ (Cu2+) complex: A possible mechanismof nigrostriatal cell damage. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1990, 283, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice-Evans, C.; Burdon, R. Free radical–Lipid interactions and their pathological consequences. Prog. Lipid Res. 1993, 32, 71–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, G.; Sabzevari, O.; Wilson, J.X.; O’Brien, P.J. Prooxidant activity and cellular effects of the phenoxyl radicals of dietary flavonoids and other polyphenolics. Toxicology 2002, 177, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minotti, G.; Aust, S.D. The role of iron in oxygen radical mediated lipid peroxidation. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1989, 71, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zupančič, Š.; Lavrič, Z.; Kristl, J. Stability and solubility of trans-resveratrol are strongly influenced by pH and temperature. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2015, 93, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.C.; Pereira-Silva, M.; Marto, J.; Chá-Chá, R.; Martins, A.; Ribeiro, H.; Veiga, F. Nanotechnology-based sunscreens—A review. Mater. Today Chem. 2022, 23, 100709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarova, M.; Stefanova, M.; Tsvetanova, E.; Georgieva, A.; Tasheva, K.; Radeva, L.; Yoncheva, K. Resveratrol-Loaded Pluronic Micelles Ameliorate Scopolamine-Induced Cognitive Dysfunction Targeting Acetylcholinesterase Activity and Programmed Cell Death. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulikovska, I.; Tsvetanova, E.; Georgieva, A.; Djeliova, V.; Radeva, L.; Yoncheva, K.; Lazarova, M. In Vitro Protective Effects of Resveratrol-Loaded Pluronic Micelles Against Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Oxidative Damage in U87MG Glioblastoma Cells. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raynova, Y.; Marchev, A.; Doumanova, L.; Pavlov, A.; Idakieva, K. Antioxidant Activity of Helix aspersa maxima (Gastropod) Hemocyanin. Acta Microbiol. Bulg. 2015, 31, 127–131. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp, C.; Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase: Improved assays and assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 1971, 44, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of ‘antioxidant power’: The FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apak, R.; Güçlü, K.; Özyürek, M.; Karademir, S.E. Novel total antioxidant capacity index for dietary polyphenols and vitamins C and E, using their cupric ion reducing capability in the presence of neocuproine: CUPRAC method. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 7970–7981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, F.; Gebinski, J.; Hoffstein, P.; Weinstein, J.; Scott, A. Swelling and lysis of rat liver mitochondria by ferrous ions. J. Biol. Chem. 1963, 238, 828–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.; Gupta, L.K.; Mediratta, P.K.; Bhattacharya, S.K. Effect of Resveratrol on Scopolamine-Induced Cognitive Impairmentin Mice. Pharmacol. Rep. 2012, 64, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennaceur, A.; Delacour, J. A new one-trial test for neurobiological studies of memory in rats. 1: Behavioral data. Behav. Brain Res. 1988, 31, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertaina-Anglade, V.; Enjuanes, E.; Morillon, D.; Drieu la Rochelle, C. The object recognition task in rats and mice: A simple and rapid model in safety pharmacology to detect amnesic properties of a new chemical entity. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 2006, 54, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Kode, A.; Biswas, S.K. Assay for quantitative determination of glutathione and glutathione disulfide levels using enzymatic recycling method. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 3159–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peskin, A.V.; Winterbourn, C.C. A microtiter plate assay for superoxide dismutase using a water-soluble tetrazolium salt (WST-1). Clin. Chim. Acta 2000, 293, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, O.; Rosebrough, N.; Farr, A.; Randall, R. Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951, 193, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taupin, P.; Ben-Ari, Y.; Roisin, M.P. Subcellular fractionation on Percoll gradient of mossy fiber synaptosomes: Evoked release of glutamate, GABA, aspartate and glutamate decarboxylase activity in control and degranulated rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 1994, 644, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungarro-Menchaca, X.; Ferrera, P.; Morán, J.; Arias, C. beta-Amyloid peptide induces ultrastructural changes in synaptosomes and potentiates mitochondrial dysfunction in the presence of ryanodine. J. Neurosci. Res. 2002, 68, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robyt, J.F.; Ackerman, R.J.; Chittenden, C.G. Reaction of protein disulfide groups with Ellman’s reagent: A case study of the number of sulfhydryl and disulfide groups in Aspergillus oryzae α-amylase, papain, and lysozyme. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1971, 147, 262–269. [Google Scholar]

- Oyaizu, M. Studies on product of browning reaction prepared from glucose amine. Jpn. J. Nut. 1986, 44, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.H.; Lin, H.R.; Yang, C.S.; Liaw, C.C.; Wang, I.C.; Chen, J.J. Bioactive Components from Ampelopsis japonica with Antioxidant, Anti- α-Glucosidase, and Antiacetylcholinesterase Activities. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejenaru, L.E.; Biţă, A.; Belu, I.; Segneanu, A.-E.; Radu, A.; Dumitru, A.; Ciocîlteu, M.V.; Mogoşanu, G.D.; Bejenaru, C. Resveratrol: A Review on the Biological Activity and Applications. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, X.; Liu, G.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Cao, Y.; Miao, J. Antioxidant Activity and Mechanism of Resveratrol and Polydatin Isolated from Mulberry (Morus alba L.). Molecules 2021, 26, 7574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Yuan, H.; Chen, C.; Liang, J.; Li, C. Study of the Antioxidant Capacity and Oxidation Products of Resveratrol in Soybean Oil. Foods 2024, 13, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B.; Gutteridge, J.M. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine; Oxford University Press: Oxford, MS, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheignon, C.; Tomas, M.; Bonnefont-Rousselot, D.; Faller, P.; Hureau, C.; Collin, F. Oxidative stress and the amyloid beta peptide in Alzheimer’s disease. Redox Biol. 2018, 14, 450–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, M.; Burwell, R.; Burchinal, M. Severity of spatial learning impairment in aging: Development of a learning index for performance in the Morris water maze. Behav. Neurosci. 2015, 129, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarova, M.I.; Tsekova, D.S.; Tancheva, L.P.; Kirilov, K.T.; Uzunova, D.N.; Vezenkov, L.T.; Tsvetanova, E.R.; Alexandrova, A.V.; Georgieva, A.P.; Gavrilova, P.T.; et al. New Galantamine Derivatives with Inhibitory Effect on Acetylcholinesterase Activity. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2021, 83, 1211–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzvetanova, E.R.; Georgieva, A.P.; Alexandrova, A.V.; Tancheva, L.P.; Lazarova, M.I.; Dragomanova, S.T.; Alova, L.G.; Stefanova, M.O.; Kalfin, R.E. Antioxidant mechanisms in neuroprotective action of lipoic acid on learning and memory of rats with experimental dementia. Bulg. Chem. Commun. 2018, 50, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Aydin, E.; Hritcu, L.; Dogan, G.; Hayta, S.; Bagci, E. The effects of inhaled Pimpinella peregrina essential oil on scopolamine-induced memory impairment, anxiety, and depression in laboratory rats. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 6557–6567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ennaceur, A. One-trial object recognition in rats and mice: Methodological and theoretical issues. Behav. Brain. Res. 2010, 215, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soellner, D.E.; Grandys, T.; Joseph, L.; Nunez, J.L. Chronic prenatal caffeine exposure impairs novel object recognition and radial arm maze behaviors in adult rats. Behav. Brain. Res. 2009, 205, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarkovic, K.; Jakovcevic, A.; Zarkovic, N. Contribution of the HNE-immunohistochemistry to modern pathological concepts of major human diseases. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 111, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramana, K.V.; Srivastava, S.; Singhal, S.S. Lipid peroxidation products in human health and disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 7147235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, S.J.; Leberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danışman, B.; Ercan-Kelek, S.; Aslan, M. Resveratrol in Neurodegeneration, in Neurodegenerative Diseases, and in the Redox Biology of the Mitochondria. Psychiatry. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2023, 33, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.C.; Lu, K.T.; Wo, Y.Y.; Wu, Y.J.; Yang, Y.L. Resveratrol Protects Rats from Aβ-induced Neurotoxicity by the Reduction of iNOS Expression and Lipid Peroxidation. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rege, S.; Geetha, T.; Broderick, T.; Babu, J. Resveratrol protects β amyloidinduced oxidative damage and memory associated proteins in H19-7 hippocampal neuronal cells. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2015, 12, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerszon, J.; Rodacka, A.; Puchała, M. Antioxidant Properties of Resveratrol and its Protective Effects in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Adv. Cell Biol. 2014, 4, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, S.; Matsuba, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Kamano, N.; Watamura, N.; Sasaguri, H.; Takado, Y.; Yoshihara, Y.; Saito, T.; Saido, T.C. Neuronal glutathione loss leads to neurodegeneration involving gasdermin activation. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, P.K.; Saharan, S.; Tripathi, M.; Murari, G. Brain glutathione levels—A novel biomarker for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Biol. Psychiatry 2015, 78, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kamra, D.N.; Agarwal, N.; Chaudhary, L.C. In vitro methanogenesis and fermentation of feeds containing oil seed cakes with rumen liquor of buffalo. Asian-Aust. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 20, 1196–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, G.; Lan, S. Implications of Antioxidant Systems in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 129–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirończuk-Chodakowska, I.; Witkowska, A.M.; Zujko, M.E. Endogenous non-enzymatic antioxidants in the human body. Adv. Med. Sci. 2018, 63, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavas, G.O.; Ayral, P.A.; Elhan, A.H. The effects of resveratrol on oxidant/antioxidant systems and their cofactors in rats. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2013, 22, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blandini, F.; Armentero, M.T. Animal models of Parkinson’s disease. FEBS J. 2012, 279, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | DPPH | ABTS | TBA |

|---|---|---|---|

| RVT | 21.9 ± 0.51 | 1.23 ± 0.02 | 0.021 ± 0.001 |

| mRVT | 34.19 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 0.016 | 0.036 ± 0.002 |

| Trolox | 41.7 ± 1.32 | 8.6 ± 0.79 | 37.6 ± 1.32 |

| Ferric-Reducing Power Assay of RVT and mRVT | Copper-Reducing Power Assay of RVT and mRVT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final Concentration (µg/mL) | Expressed as Trolox Equivalent (ET), µM | Final Concentration (µg/mL) | Expressed as Trolox Equivalent (ET), µM | ||

| RVT | mRVT | RVT | mRVT | ||

| 0.52 | 1.77 ± 0.01 | 3.02 ± 0.03 | 2.08 | 21.34 ± 1.23 | 6.20 ± 0.05 |

| 1.04 | 1.78 ± 0.2 | 3.68 ± 0.13 | 4.16 | 49.47 ± 2.22 | 30.32 ± 1.37 |

| 2.08 | 2.71 ± 0.05 | 5.33 ± 0.06 | 8.33 | 82.64 ± 3.45 | 59.75 ± 2.76 |

| 4.17 | 3.76 ± 0.07 | 6.67 ± 0.23 | 16.67 | 143.77 ± 4.25 | 106.94 ± 5.12 |

| 8.33 | 5.20 ± 0.21 | 7.80 ± 0.32 | 33.33 | 230.68 ± 2.91 | 184.98 ± 3.46 |

| 16.67 | 6.09 ± 0.07 | 8.31 ± 0.16 | 66.67 | 260.87 ± 4.35 | 240.59 ± 3.86 |

| 33.33 | 6.70 ± 0.04 | 8.57 ± 0.18 | 133.33 | 264.33 ± 3.21 | 241.00 ± 3.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lazarova, M.; Tsvetanova, E.; Georgieva, A.; Stefanova, M.; Tasheva, K.; Radeva, L.; Kondeva-Burdina, M.; Yoncheva, K. Antioxidant and Neuroprotective Capacity of Resveratrol-Loaded Polymeric Micelles in In Vitro and In Vivo Models with Generated Oxidative Stress. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010063

Lazarova M, Tsvetanova E, Georgieva A, Stefanova M, Tasheva K, Radeva L, Kondeva-Burdina M, Yoncheva K. Antioxidant and Neuroprotective Capacity of Resveratrol-Loaded Polymeric Micelles in In Vitro and In Vivo Models with Generated Oxidative Stress. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010063

Chicago/Turabian StyleLazarova, Maria, Elina Tsvetanova, Almira Georgieva, Miroslava Stefanova, Krasimira Tasheva, Lyubomira Radeva, Magdalena Kondeva-Burdina, and Krassimira Yoncheva. 2026. "Antioxidant and Neuroprotective Capacity of Resveratrol-Loaded Polymeric Micelles in In Vitro and In Vivo Models with Generated Oxidative Stress" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010063

APA StyleLazarova, M., Tsvetanova, E., Georgieva, A., Stefanova, M., Tasheva, K., Radeva, L., Kondeva-Burdina, M., & Yoncheva, K. (2026). Antioxidant and Neuroprotective Capacity of Resveratrol-Loaded Polymeric Micelles in In Vitro and In Vivo Models with Generated Oxidative Stress. Biomedicines, 14(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010063