1. Introduction

Hypospadias is a common congenital malformation of the male genitourinary system, affecting approximately 1 in 300 live births. It is characterized by an abnormally positioned urethral opening and underdevelopment of the ventral aspect of the penis [

1], often accompanied by structural abnormalities of the corpus spongiosum surrounding the urethral plate.

Gearhart et al. [

2] described morphological defects in the corpus spongiosum, noting that its distal portion forms a bifurcated columnar structure on both sides of the urethral plate, extending distally to merge with the glans. Subsequent studies by Baskin [

3] and Putte [

4] revealed irregular dilation of vascular sinuses in the fetal corpus spongiosum and glans. Our previous work further demonstrated that a key pathological feature of the urethral corpus spongiosum in hypospadias is thickening of the vascular smooth muscle layer [

5], which was similar to the pathological changes seen in erectile dysfunction (ED), where vascular density decreases and vessel walls become thickened. These findings suggest that abnormalities in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) may contribute to the pathogenesis of hypospadias

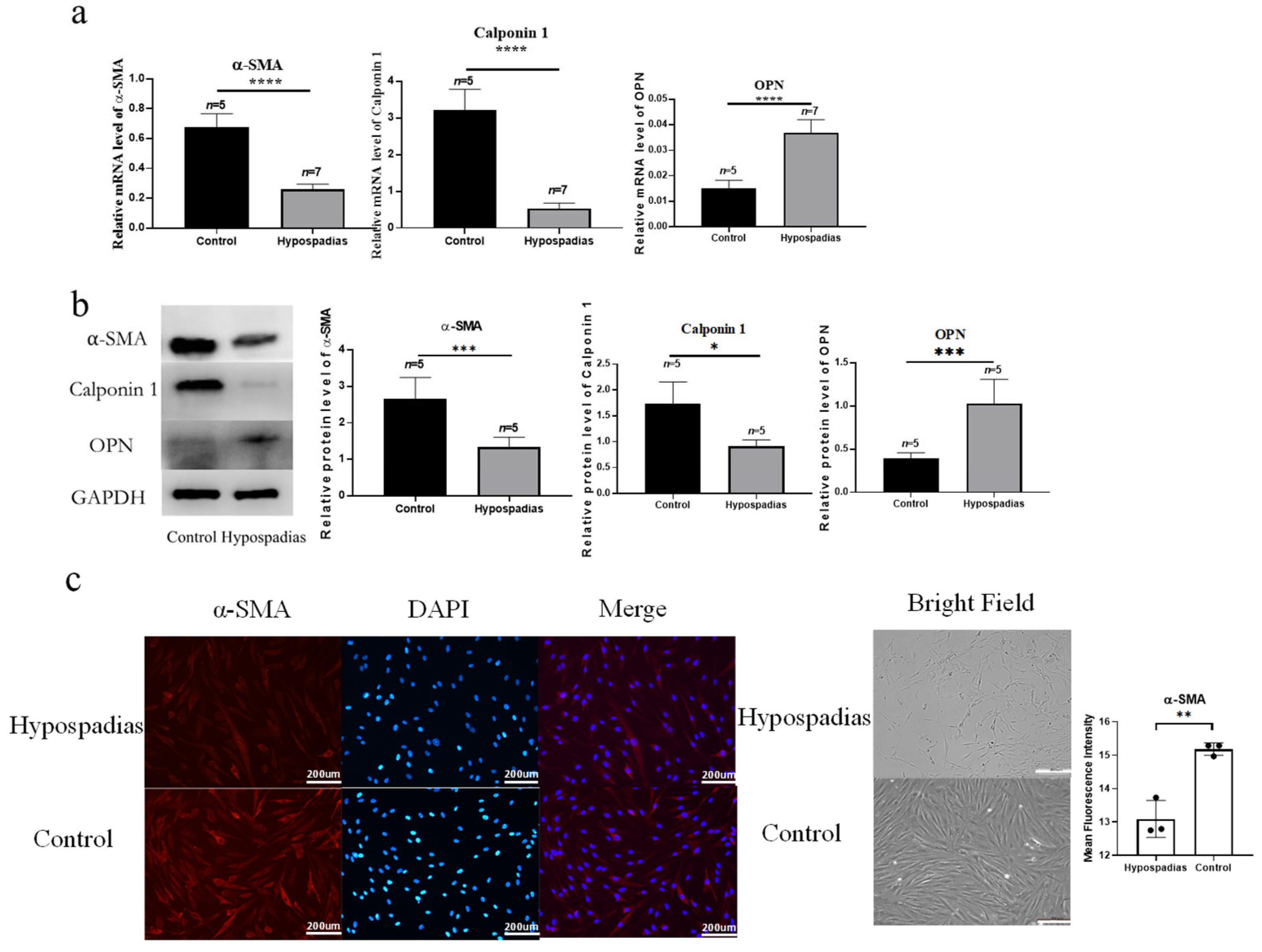

VSMCs are highly plastic cells capable of reversible transitions between contractile and synthetic phenotypes in response to environmental cues. In our earlier research, we observed phenotypic alterations of VSMCs within the urethral corpus spongiosum in hypospadias, supporting the notion that such phenotypic modulation may underlie the abnormal structure of the corpus spongiosum [

6]. Our previous study mainly described phenotypic alterations of vascular smooth muscle cells in hypospadias [

6]. In the present work, we extend these observations by using RNA sequencing combined with weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) to explore the upstream molecular mechanisms underlying this phenotypic switch.

Based on these findings, we hypothesized that VSMC phenotypic switching plays a critical role in the abnormal remodeling of the corpus spongiosum in hypospadias. To unbiasedly explore upstream regulators of this process, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) to compare gene expression profiles between hypospadias and control tissues, and applied Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) to identify gene modules and hub genes associated with the hypospadias phenotype. We then focused on the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor CDKN2B, a hub gene within the most strongly hypospadias-associated module, and investigated its role in regulating VSMCs phenotypic transformation and associated signaling pathways.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Children’s Hospital (No. 2021RY033-E01). The experimental group comprised seven patients with scrotal hypospadias (mean age: 29.14 ± 15.27 months). Corpus spongiosum tissue was obtained from both sides of the forked urethral plate during surgical repair. The control group included five patients with urethral stricture secondary to trauma (mean age: 15.80 ± 8.81 years); samples of normal corpus spongiosum tissue adjacent to the stricture site were collected as control group [

5].

2.2. RNA Sequencing (RNA-seq) and Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA)

Total RNA was extracted from corpus spongiosum tissue using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA). RNA libraries were constructed using the TruSeq RNA Library Prep Kit v2 (Illumina, Inc, San Diego, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol and sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform with 150 bp paired-end reads.

Raw sequencing reads were processed using Skewer to remove adaptor sequences and low-quality fragments. Read quality was assessed with FastQC (

www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/, accessed on 1 January 2023). Clean reads were aligned to the human reference genome (GRCh38) using STAR, and transcript assembly was performed with StringTie (v2.2.1) using Ensembl (v110) annotations. Gene expression levels were quantified as FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped fragments).

Differential gene expression was analyzed using the DESeq2 package in R (v4.3.2.) Genes with |log2 fold change| ≥ 1 and adjusted p < 0.05 (false discovery rate, FDR) were considered significantly differentially expressed. Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG pathway analyses were performed to explore functional enrichment of the identified genes.

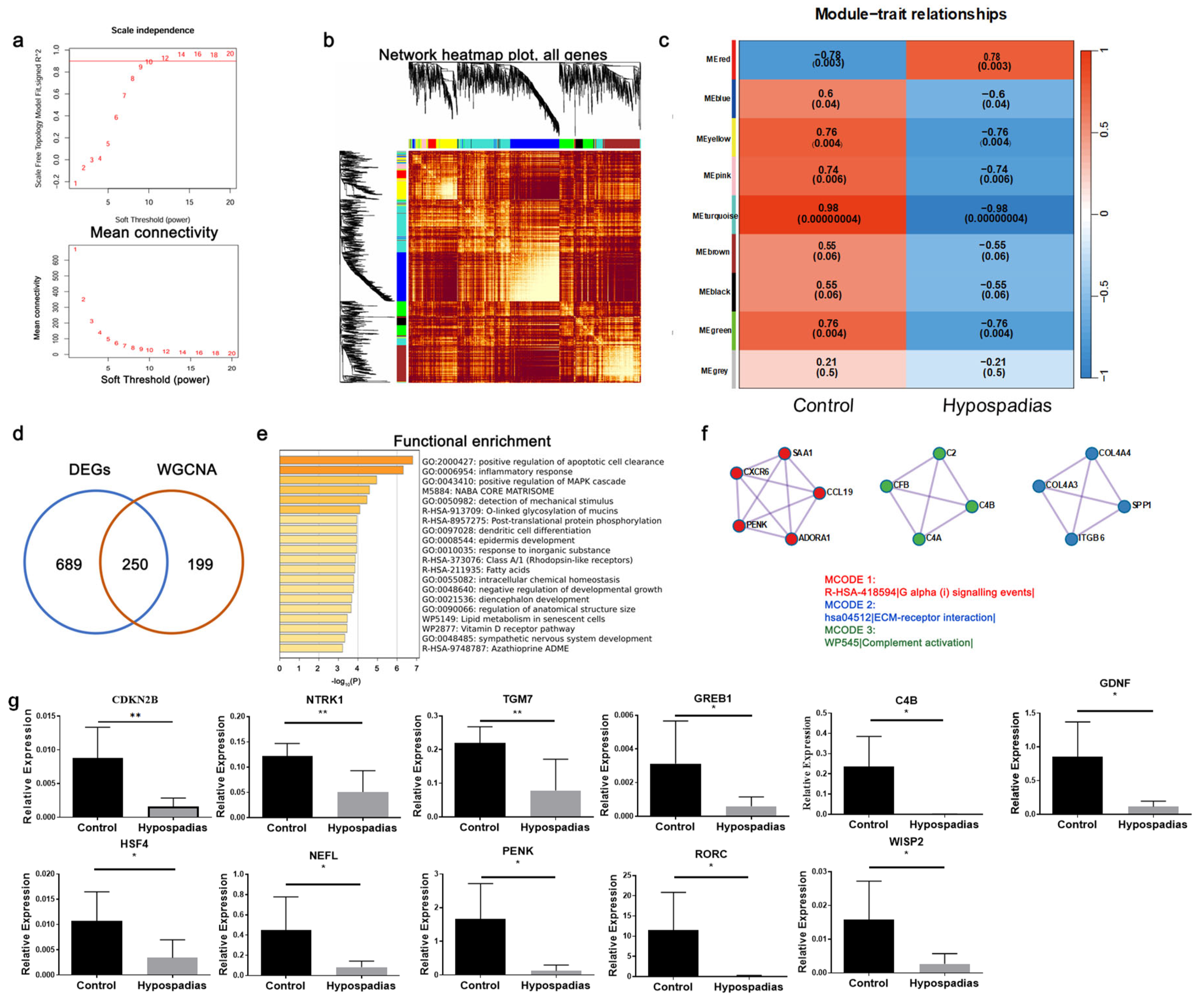

The present study employed the WGCNA package (v1.73) in R software to cluster functional modules in RNA-seq data, utilizing a defined cut-off height of 0.25 to merge similar modules. The co-expression network was integrated with group phenotypes (control vs. hypospadias), and hub genes with high modularity were identified through modular-trait correlation analysis. A heatmap was utilized to visualize the correlation between gene modules and clinical traits, followed by the identification of modules associated with co-expression patterns (turquoise module) and phenotypes. The shared genes between DEGs and WGCNA hub genes were obtained through the utilization of Venny.2, version 2.1.0, an online tool for VENN analysis. The identification of crucial pathways involved in phenotypic switching was achieved by analyzing the shared genes, utilizing Metascape (

http://metascape.org/, accessed on 1 January 2023).

2.3. Histological Studies and Immunohistochemical Staining

The tissue samples were fixed in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 6 h, then embedded in paraffin and consecutively sectioned. To observe the structure of corpus spongiosum, HE staining was performed. The expression and distribution of the target protein were observed through immunohistochemical staining using the DAB method.

2.4. Real-Time Fluorescent Quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and reverse-transcribed to cDNA using a reverse transcription kit (Takara, kusatsu shiga, Japan). qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green Master Mix in a 10 μL reaction system under the following cycling conditions: 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s.

Primer sequences for target genes (α-SMA, Calponin 1, OPN, SRF, MYOCD, SMAD2, SMAD3, TGF-β1, FOXO4, and KLF4) were designed based on published human sequences (

Table S1).

2.5. Western Blot

Tissue samples were lysed in RIPA buffer and centrifuged to obtain protein extracts. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA assay. Equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS–PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and blocked for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against CDKN2B, β-actin, GAPDH, α-SMA, Calponin 1, OPN, TGF-β1, Smad2, and Smad3 (Abcam or CST; dilutions 1:500–1:1000). After incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, signals were detected using an ECL chemiluminescence system, and relative expression levels were quantified by grayscale analysis

2.6. Primary Cell Culture

Fresh corpus spongiosum tissue was rinsed in PBS (Gibco, NY, USA), minced into approximately 1 mm3 fragments, and digested with type IV collagenase for 30 min at 37 °C. The digested mixture was centrifuged, washed with prewarmed medium, and transferred to 24-well plates containing a commercially available smooth muscle cell medium (Smooth Muscle Cell Medium, ScienCell, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with the manufacturer’s smooth muscle growth supplement and 1% penicillin–streptomycin. Cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. The medium was changed every two days, and cells were subcultured upon reaching 80–90% confluence.

2.7. Cell Immunofluorescence Staining

The protocol involved fixing cells with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilizing them with 0.5% Triton X-100, incubating with a primary antibody against α-SMA (a marker of smooth muscle cells), and then incubating with a secondary antibody conjugated with a fluorescent dye. The nuclei were stained with DAPI, a fluorescent DNA-binding dye. The cells were then visualized under a fluorescence microscope, which allows for the visualization of the fluorescent signals emitted by the secondary antibody and the DAPI stain.

2.8. Cell Transfection

Lentiviral vectors encoding CDKN2B overexpression (oeRNA) or CDKN2B knockdown (shRNA) constructs were obtained from Shanghai Hanheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Lentiviral particles were produced by co-transfecting the constructs with packaging and envelope plasmids into 293T cells. Primary VSMCs were infected with lentivirus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 (1 × 108 TU/mL). The experimental groups were as follows:

Control group (blank lentiviral control);

ko-CDKN2B group (CDKN2B shRNA-infected controls);

Hypospadias group (blank lentiviral infection in hypospadias-derived VSMCs);

oe-CDKN2B group (CDKN2B overexpression in hypospadias-derived VSMCs).

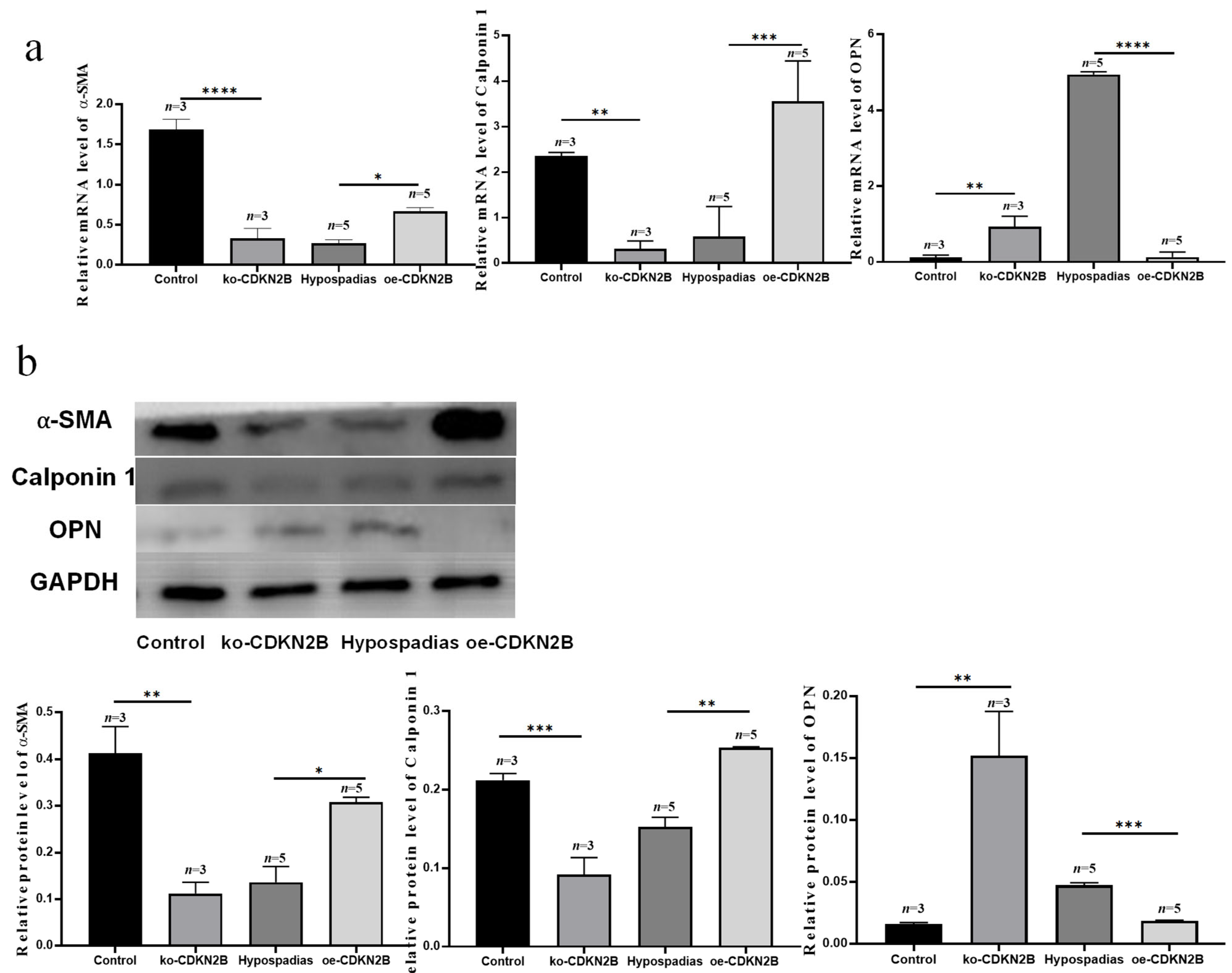

Thus, CDKN2B was knocked down in control-derived VSMCs and overexpressed in hypospadias-derived VSMCs to examine loss- and gain-of-function effects in complementary cellular backgrounds.

2.9. TGF-β1 Supplement

After establishing primary cultures of hypospadias-derived VSMCs, recombinant TGF-β1 protein (Abclonal, Wuhan, China) was added to the culture medium at a final concentration of 1 μg/mL. Cells were maintained for 7 days to evaluate the effect of exogenous TGF-β1 stimulation [

7].

2.10. Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). For normally distributed data with homogenous variance, comparisons between two groups were performed using an unpaired Student’s t-test, and multiple-group comparisons were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Nonparametric data were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. A two-sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

4. Discussion

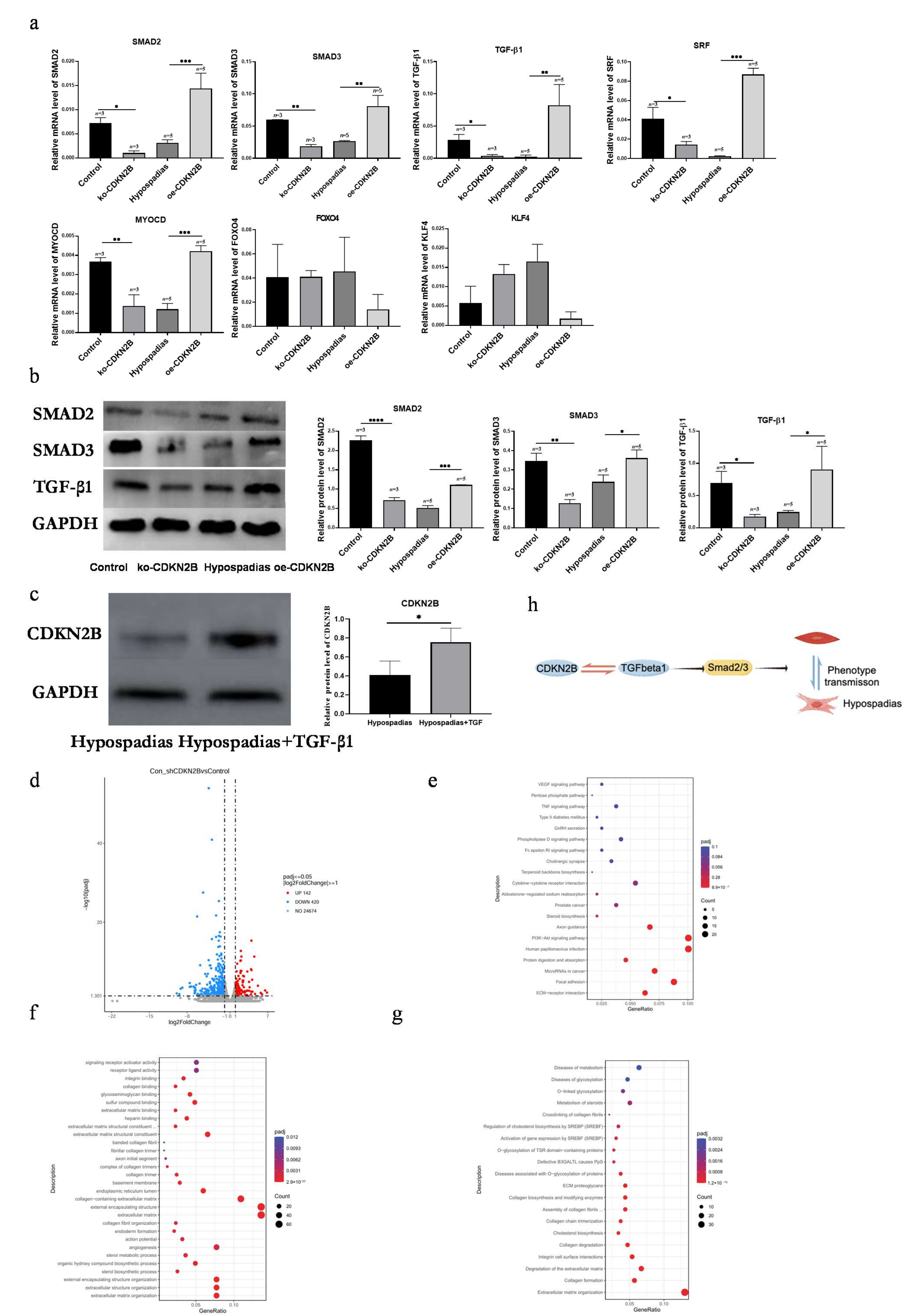

In summary, our findings demonstrate that downregulation of

CDKN2B in vascular smooth muscle tissue of the corpus spongiosum from patients with hypospadias is associated with a phenotypic switch of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) from a contractile to a secretory state. This phenotypic transition contributes to the abnormal vascular composition of the corpus spongiosum in hypospadias. Mechanistically, this process appears to be mediated through the

CDKN2B–TGF/Smad signaling axis (

Figure 5h). Taken together, our findings indicate that CDKN2B plays a crucial role in regulating the phenotypic switch of corpus spongiosum VSMCs in hypospadias. This study therefore builds on our previous phenotypic observations [

6] by providing a systems-level view of the regulatory network (via RNA-seq and WGCNA) and highlighting CDKN2B-centered signaling as a key mechanistic axis.

Hypospadias is a congenital malformation of the ventral penis characterized by incomplete development of the urethral spongiosum. Morphologically, the distal corpus spongiosum often presents as bifurcated columnar structures extending bilaterally along the urethral plate and merging with the glans penis. Histological observations by Baskin [

3] and Putte [

4] on fetal specimens confirmed the irregular dilation of vascular spaces in the urethral and penile spongiosum, consistent with aberrant tissue morphogenesis. Our previous work further showed that vascular abnormalities—such as loosely arranged vascular sinusoids, enlarged vascular cavities, and thickened vascular smooth muscle layers—are key features of the corpus spongiosum in hypospadias [

5]. These findings collectively suggest that abnormal VSMC behavior plays a central role in hypospadias-related vascular malformation. Consistent with this, our earlier studies revealed a phenotypic transformation of spongiosal VSMCs from the contractile to the synthetic type [

6].

VSMCs exhibit two interconvertible phenotypes: the contractile phenotype, which maintains vascular tone and structural stability under physiological conditions, and the secretory phenotype, which is characterized by enhanced extracellular matrix (ECM) synthesis and active proliferation. Contractile VSMCs express markers such as α-SMA and Calponin 1, whereas secretory VSMCs predominantly express OPN [

10].

Under normal physiological conditions, VSMCs are primarily contractile; however, they retain remarkable plasticity and can transition between phenotypes in response to environmental cues. For instance, PDGF-BB promotes differentiation toward the contractile type, maintaining mature vessel integrity, while vascular injury or inflammatory cytokines—mediated through

KLF4 and other transcription factors—induce conversion to the secretory phenotype [

11]. Excessive or dysregulated phenotypic switching contributes to disease progression, such as in atherosclerosis, where over-proliferation of secretory VSMCs thickens the vessel wall and increases secretion of inflammatory mediators like IL-1β [

12].

In erectile dysfunction (ED), Lv et al. [

13] and Zhang et al. [

14] demonstrated that hypoxia and diabetes induce phenotypic transformation of penile cavernosal VSMCs, and that restoration of contractile markers α-SMA and Calponin 1 correlates with improved erectile function. Our study is the first to demonstrate that such VSMC phenotypic transformation occurs in hypospadias, a congenital developmental anomaly. Reduced expression of contractile markers (α-SMA, Calponin 1) and elevated expression of secretory marker OPN indicate a switch toward the secretory phenotype, which likely contributes to the abnormal vascular architecture of the corpus spongiosum in hypospadias.

RNA-seq analysis identified 1568 DEGs in hypospadias tissues, including 334 upregulated and 1234 downregulated genes. Enrichment analyses indicated significant involvement of pathways regulating protein metabolism and muscle structural organization, both crucial for VSMC phenotypic modulation (

Figure S1). To refine the identification of functional gene modules, we applied Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA), which has greater sensitivity than DEG analysis in revealing gene–trait correlations [

15]. Importantly, by combining RNA-seq with WGCNA we were able to move beyond single-gene comparisons and identify gene modules most tightly associated with the hypospadias phenotype. The turquoise module showed a strong negative correlation with hypospadias (

Figure 2c), and overlap analysis between DEGs and WGCNA hub genes (

Figure 2d) highlighted

CDKN2B as a pivotal hub gene within this module. This systems-level approach strengthens the argument that

CDKN2B is not only differentially expressed but is embedded in a co-regulated network relevant to corpus spongiosum remodeling.

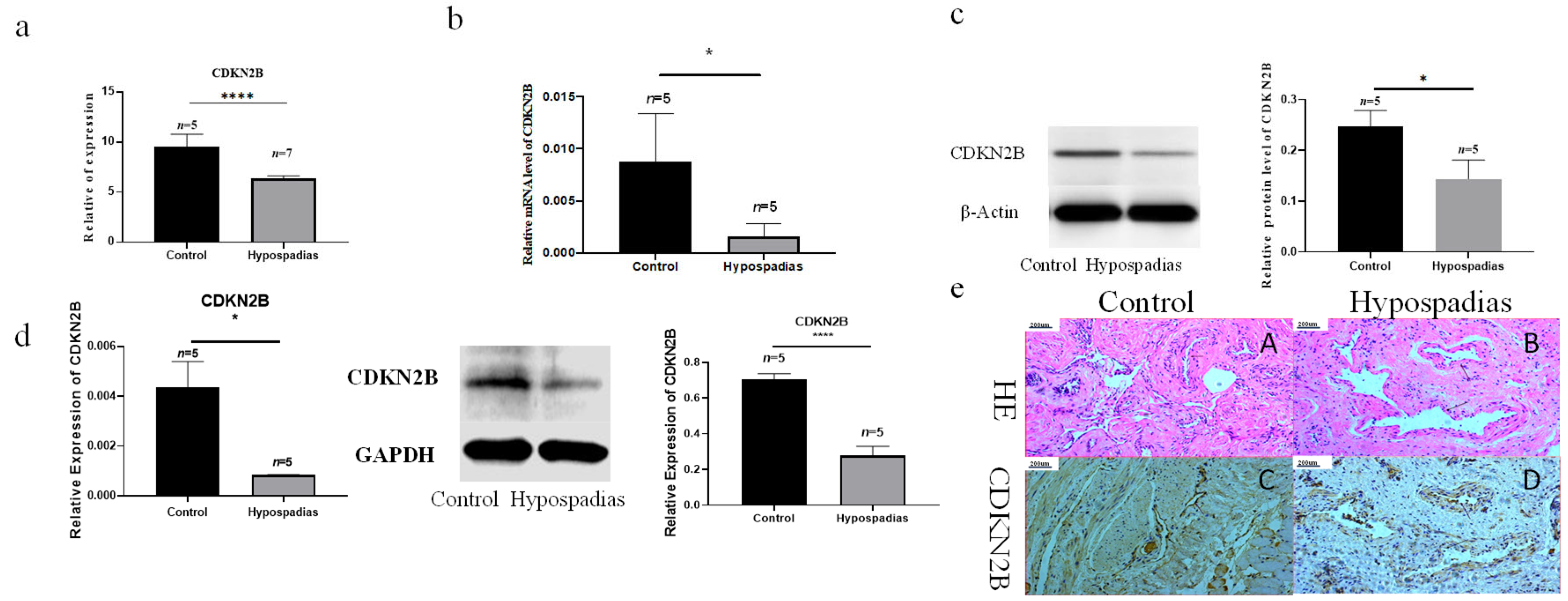

The INK4b-ARF-INK4a locus on chromosome 9p21, which includes

CDKN2B, is strongly associated with coronary artery disease and atherosclerosis.

CDKN2B, encoding the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2B, has been implicated in regulating VSMC proliferation and differentiation. Kojima et al. [

16] reported that

CDKN2B loss reduces Calponin synthesis, expands the lipid-rich necrotic core in plaques, and promotes the emergence of secretory VSMCs, thereby accelerating atherosclerosis. Similarly, our RNA-seq results revealed significantly lower

CDKN2B expression in hypospadias, implicating its dysregulation in the abnormal development of the spongiosum vasculature.

In cardiovascular pathology,

CDKN2B influences VSMC phenotype via

SRF (serum response factor) and

MYOCD (myocardin). Scruggs et al. [

17]. demonstrated that reduced

CDKN2B expression elevates

MRTFA, a co-activator of

SRF/MYOCD, leading to aberrant VSMC differentiation.

SRF activates transcription of contractile genes through CArG-box binding [

18]. while

MYOCD acts as a co-activator that promotes expression of contractile proteins such as α-SMA, SM-MHC, SM22α, and Calponin 1. Reduced SRF levels, as observed in atherosclerotic plaques, impair cell cycle regulation and exacerbate vascular pathology [

19]. Overexpression of

MYOCD in cavernosal tissue of ED rat models restores contractile VSMCs and improves erectile function [

14].

Consistent with these studies, we found that decreased CDKN2B expression in hypospadias correlates with reduced SRF/MYOCD signaling, diminished α-SMA and Calponin 1, and increased OPN, suggesting that loss of CDKN2B may drive VSMCs toward a secretory phenotype, contributing to vascular malformation of the corpus spongiosum.

Our findings further establish that

CDKN2B modulates VSMC phenotypic switching through the

TGF-β/Smad pathway. Li et al. [

20] demonstrated high TGF-β1 expression in the urethral folds of male fetal rats, emphasizing its role in urethral fusion, while Zhou et al. [

21]. showed that

TGF-β/Smad signaling participates in epithelial–mesenchymal transition during urethral morphogenesis.

TGF-β signaling is also essential for embryonic vascular development; its deficiency results in disorganized vasculature and abnormal vessel lumen formation [

22]. In our study, overexpression of

CDKN2B activated

TGF-β/Smad signaling and upregulated contractile gene expression, promoting the secretory-to-contractile transition in VSMCs. These results reveal a previously unrecognized interaction between

CDKN2B and

TGF-β/Smad signaling in urethral vascular development, providing new insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying hypospadias-related vascular malformation.

Our study has several limitations. First, age-matched normal pediatric corpus spongiosum tissue is difficult to obtain, and our control samples were derived from older patients with traumatic urethral stricture. Although we sampled grossly normal tissue adjacent to the stricture and used the same processing procedures for both groups, age and clinical background differences could still influence gene expression profiles. Second, we defined primary cultures as VSMCs based on spindle-shaped morphology and strong α-SMA expression; however, α-SMA can also be expressed by activated fibroblasts, and a minor fibroblast contribution cannot be excluded. Third, our lentiviral experiments focused on CDKN2B knockdown in control-derived VSMCs and overexpression in hypospadias-derived VSMCs. Additional experimental groups—such as CDKN2B overexpression in control VSMCs and knockdown in hypospadias VSMCs—would provide an even more comprehensive assessment of CDKN2B function but were not feasible due to limited patient-derived material. Finally, in vivo functional validation in animal models is needed to confirm causality and to dissect temporal dynamics of CDKN2B-dependent signaling during urethral development.

Despite these limitations, our data identify CDKN2B as a novel molecular link between VSMC phenotypic switching and abnormal vascular remodeling of the corpus spongiosum in hypospadias and highlight the CDKN2B–TGF/Smad–SRF/MYOCD axis as a potential therapeutic target