A Retrospective Observational Study of Pulmonary Impairments in Long COVID Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Pulmonary Function Test Assessment

2.3. Data Source and Management

2.4. Study Outcomes

2.5. Ethical Approval

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Participants

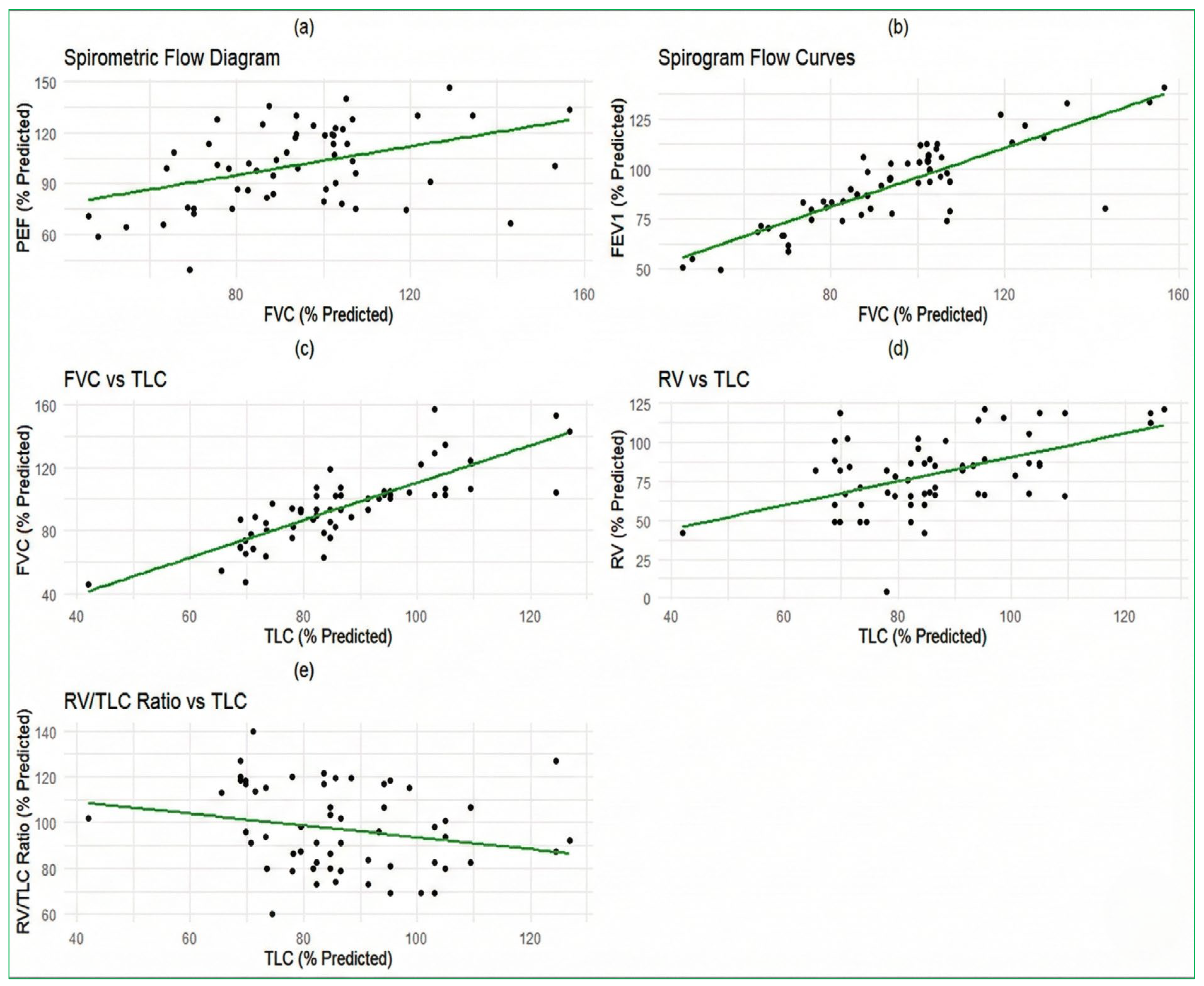

3.2. Pulmonary Function Test

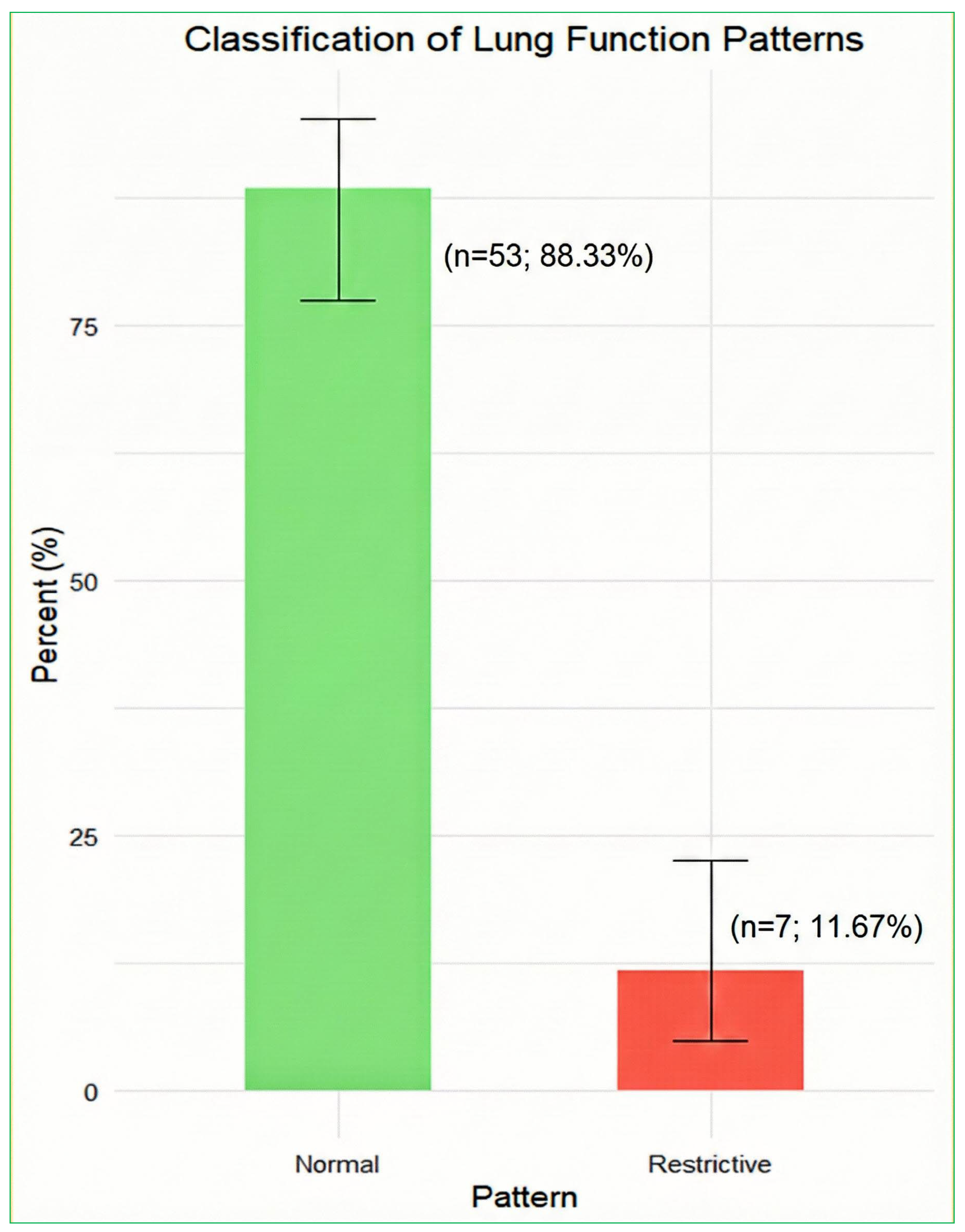

3.3. Lung Function Patterns

3.4. Radiographic and Tomographic Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARDS | Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| CXR | Chest X-Ray |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| DLCO | Diffusing Capacity of the Lungs for Carbon Monoxide |

| FVC | Forced Vital Capacity |

| FEV1 | Forced Expiratory Volume in One Second |

| FRC | Functional Residual Capacity |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| ILD | Interstitial Lung Disease |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| PFT | Pulmonary Function Test |

| RV | Residual Volume |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| TLC | Total Lung Capacity |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

References

- Yong, S. Long COVID or Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: Putative Pathophysiology, Risk Factors, and Treatments. Infect. Dis. 2021, 53, 737–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuliano, M.; Tiple, D.; Agostoni, P.; Armocida, B.; Biardi, L.; Bonfigli, A.R.; Campana, A.; Ciardi, M.; Di Marco, F.; Floridia, M.; et al. Italian Good Practice Recommendations on Management of Persons with Long-COVID. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1122141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, G. Exercise Is the Most Important Medicine for COVID-19. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2023, 22, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahal, A.; Pohl, G.; Laxmi, R.; Devkota, T.P.; Gurung, S. Long COVID-19 Effects (Chronic COVID-19 Syndrome) in Nepalese Cohort Recovered from SARS-CoV-2 Infection. J. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2023, 6, 1884–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideratou, C. Persisting Shadows: Unravelling the Impact of Long COVID-19 on Respiratory, Cardiovascular, and Nervous Systems. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2023, 15, 806–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somalwar, S. Long COVID and Perimenopause. J. South Asian Fed. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2024, 16, 174–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalski, J.E.; Kurche, J.S.; Schwartz, D.A. From ARDS to Pulmonary Fibrosis: The Next Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic? Transl. Res. 2022, 241, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Peng, F.; Zhou, Y. Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Short- or Long-Term Sequela of Severe COVID-19? Chin. Med. J. Pulm. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 1, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajjar, L.A.; Costa, I.B.S.; Rizk, S.I.; Biselli, B.; Gomes, B.R.; Bittar, C.S.; de Oliveira, G.Q.; de Almeida, J.P.; de Oliveira Bello, M.V.; Garzillo, C.; et al. Intensive Care Management of Patients with COVID-19: A Practical Approach. Ann. Intensive Care 2021, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myall, K.; Mukherjee, B.; West, A. How COVID-19 Interacts with Interstitial Lung Disease. Breathe 2022, 18, 210158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mart, M.F.; Ware, L.B. The Long-Lasting Effects of the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2020, 14, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijts, T.; Witvliet, M.G.; Balaj, M.; Eikemo, T.A. Assessing the Long-Term Health Impact of COVID-19: The Importance of Using Self-Reported Health Measures. Scand. J. Public Health 2023, 51, 645–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, S.; Sharma, P.; Harishkumar, A.; Rai, D.K. Post-COVID-19 Pulmonary Fibrosis: Report of Two Cases. EMJ Respir. 2021, 10, 2028–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweis, J. From Acute Infection to Prolonged Health Consequences: Understanding Health Disparities and Economic Implications in Long COVID Worldwide. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheibe, E. The Multisystem Effects of Long COVID Syndrome and Potential Benefits of Massage Therapy in Long COVID Care. Int. J. Ther. Massage Bodywork Res. Educ. Pract. 2024, 17, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalbandian, A.; Sehgal, K.; Gupta, A.; Madhavan, M.V.; McGroder, C.; Stevens, J.S.; Cook, J.R.; Nordvig, A.S.; Shalev, D.; Sehrawat, T.S.; et al. Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crook, H.; Raza, S.; Nowell, J.; Young, M.; Edison, P. Long COVID—Mechanisms, Risk Factors, and Management. BMJ 2021, 374, n1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation (WHO). A Clinical Case Definition of Post COVID-19 Condition by a Delphi Consensus; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). COVID-19 Rapid Guideline: Managing the Long-Term Effects of COVID-19 (NG188); NICE: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, S.; Liu, S. Proposed Subtypes of Post-COVID-19 Syndrome (or Long-COVID) and Their Respective Potential Therapies. Rev. Med. Virol. 2021, 32, e2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Respiratory Society (ERS). European Respiratory Society Statement on Long COVID Follow-Up. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 58, 2102174. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, X.; Jian, W.; Su, Z.; Chen, M.; Peng, H.; Peng, P.; Lei, C.; Chen, R.; Zhong, N.; Li, S. Abnormal Pulmonary Function in COVID-19 Patients at Time of Hospital Discharge. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, 2001217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnweber, T.; Sahanic, S.; Pizzini, A.; Luger, A.; Schwabl, C.; Sonnweber, B.; Kurz, K.; Koppelstätter, S.; Haschka, D.; Petzer, V.; et al. Cardiopulmonary Recovery after COVID-19—An Observational Prospective Multicentre Trial. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 57, 2003481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asimakos, A.T.; Vassiliou, A.G.; Keskinidou, C.; Spetsioti, S.; Antonoglou, A.; Vrettou, C.S.; Mourelatos, P.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Pratikaki, M.; Athanasiou, N.; et al. Persistent Endothelial Lung Damage and Impaired Diffusion Capacity in Long COVID. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yelin, D.; Ghantous, N.; Awwad, M.; Daitch, V.; Kalfon, T.; Mor, M.; Buchrits, S.; Shafir, Y.; Shapira-Lichter, I.; Leibovici, L.; et al. Pulmonary Diffusing Capacity among Individuals Recovering from Mild to Moderate COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.-M.; Shang, Y.-M.; Song, W.-B.; Li, Q.-Q.; Xie, H.; Xu, Q.-F.; Jia, J.-L.; Li, L.-M.; Mao, H.-L.; Zhou, X.-M.; et al. Follow-Up Study of the Pulmonary Function and Related Physiological Characteristics of COVID-19 Survivors Three Months After Recovery. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 25, 100463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, S. Pulmonary Features of Long COVID-19: Where Are We Now? J. Clin. Oncol. Rep. 2023, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montani, D.; Savale, L.; Noël, N.; Meyrignac, O.; Colle, R.; Gasnier, M.; Corruble, E.; Beurnier, A.; Jutant, E.M.; Pham, T.; et al. Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2022, 31, 210185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazdar, S.; Kwee, A.K.A.L.; Houweling, L.; de Wit-van Wijck, Y.; Mohamed Hoesein, F.A.A.; Downward, G.S.; Nossent, E.J.; Maitland-van der Zee, A.H.; on behalf of the P4O2 Consortium. A Systematic Review of Chest Imaging Findings in Long COVID Patients. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce, M.C.; Sankari, A.; Sharma, S. Pulmonary Function Tests. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Funke-Chambour, M.; Bridevaux, P.-O.; Clarenbach, C.F.; Soccal, P.M.; Nicod, L.P.; von Garnier, C.; on behalf of the Swiss COVID Lung Study Group and the Swiss Society of Pulmonology. Swiss Recommendations for the Follow-Up and Treatment of Pulmonary Long COVID. Respiration 2021, 100, 826–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppini, N.; Fira-Mladinescu, O.; Traila, D.; Motofelea, A.C.; Marc, M.S.; Manolescu, D.; Vastag, E.; Maganti, R.K.; Oancea, C. Longitudinal Analysis of Pulmonary Function Impairment One Year Post-COVID-19: A Single-Center Study. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aritonang, M.E.; Pandia, P.; Pradana, A.; Ashar, T. Factors Associated with Small Airway Obstruction in COVID-19 Survivors: A Cross-Sectional Study Among Health-Care Providers. Narra J. 2023, 3, e437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teles, G.B.D.S.; Fonseca, E.K.U.N.; Capobianco, J.; Yokoo, P.; Rosa, M.E.E.; Antunes, T.; Bernardes, C.S.; Marques, T.C.; Chate, R.C.; Szarf, G. Correlation Between Chest Computed Tomography Findings and Pulmonary Function Test Results in the Post-Recovery Phase of COVID-19. Einstein 2023, 21, eAO0288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrajhi, N.N. Post-COVID-19 Pulmonary Fibrosis: An Ongoing Concern. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2023, 18, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Price, O.J.; Hull, J.H. Pulmonary Function and COVID-19. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2021, 21, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laveneziana, P.; Straus, C.; Meiners, S. How and to What Extent Immunological Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Shape Pulmonary Function in COVID-19 Patients. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 628288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vontetsianos, A.; Chynkiamis, N.; Anagnostopoulou, C.; Lekka, C.; Zaneli, S.; Anagnostopoulos, N.; Rovina, N.; Kampolis, C.F.; Papaioannou, A.I.; Kaltsakas, G.; et al. Small Airways Dysfunction and Lung Hyperinflation in Long COVID-19 Patients as Potential Mechanisms of Persistent Dyspnoea. Adv. Respir. Med. 2024, 92, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimmino, G.; D’Elia, S.; Morello, M.; Titolo, G.; Luisi, E.; Solimene, A.; Serpico, C.; Conte, S.; Natale, F.; Loffredo, F.S.; et al. Cardio-Pulmonary Features of Long COVID: From Molecular and Histopathological Characteristics to Clinical Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkissoon, R. Journal Club: The Intersection of Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Coronavirus Disease 2019 and COPD. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2021, 8, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poerio, A.; Carlicchi, E.; Lotrecchiano, L.; Praticò, C.; Mistè, G.; Scavello, S.; Morsiani, M.; Zompatori, M.; Ferrari, R. Evolution of COVID-19 Pulmonary Fibrosis-Like Residual Changes over Time: Longitudinal Chest CT up to 9 Months After Disease Onset. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2022, 4, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Feng, Q.; Yuan, X.; Lu, C.; Wang, S.; Yuan, Y. Diagnostic Value of Lung Function Tests in Long COVID: Analysis of Positive Bronchial Provocation Test Outcomes. Front. Med. 2025, 11, 1512658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bretas, D.C.; Leite, A.S.; Mancuzo, E.V.; Prata, T.A.; Andrade, B.H.; Oliveira, J.d.G.F.; Batista, A.P.; Machado-Coelho, G.L.L.; Augusto, V.M.; Marinho, C.C. Lung Function Six Months After Severe COVID-19: Does Time, in Fact, Heal All Wounds? Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 26, 102352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, S.S.; Ghorpade, D.; Dhoori, S.; Dhar, R.; Dumra, H.; Chhajed, P.N.; Bhattacharya, P.; Rajan, S.; Talwar, D.; Christopher, D.J.; et al. Role of Antifibrotic Drugs in the Management of Post-COVID-19 Interstitial Lung Disease: A Review of Literature and Expert Working Group Report. Lung India 2022, 39, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durak, G.; Akin, K.; Cetin, O.; Uysal, E.; Aktas, H.E.; Durak, U.; Karkas, A.Y.; Senkal, N.; Savas, H.; Tunaci, A.; et al. Radiologic and Clinical Correlates of Long-Term Post-COVID-19 Pulmonary Sequelae. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treasa, S. Post-COVID Pulmonary Fibrosis: Pathophysiological Mechanisms, Diagnostic Tools, and Emerging Therapies. J. Pulmonol. Respir. Res. 2025, 9, 009–013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konkol, S.B.; Ramani, C.; Martin, D.N.; Harnish-Cruz, C.K.; Mietla, K.M.; Sessums, R.F.; Widere, J.C.; Kadl, A. Differences in Lung Function between Major Race/Ethnicity Groups Following Hospitalisation with COVID-19. Respir. Med. 2022, 201, 106939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, D.J.; Isaac, B.T.J.; John, F.B.; Shankar, D.; Samuel, P.; Gupta, R.; Thangakunam, B. Impact of Post-COVID-19 Lung Damage on Pulmonary Function, Exercise Tolerance and Quality of Life in Indian Subjects. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0002884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, M.A.; Malhotra, A.; Non, A.L. Could Routine Race-Adjustment of Spirometers Exacerbate Racial Disparities in COVID-19 Recovery? Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 124–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Bai, W.; Yue, J.; Qin, L.; Zhang, C.; Xu, S.; Liu, X.; Ni, W.; Xie, M. Eight months follow-up study on pulmonary function, lung radiographic, and related physiological characteristics in COVID-19 survivors. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Xu, J.; Liao, T.; Yin, Z.; Yang, F.; Wang, K.; Wang, Z.; Yang, D.; Wang, S.; Peng, Y.; et al. Comparison of residual pulmonary abnormalities 3 months after discharge in patients who recovered from COVID-19 of different severity. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 682087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Willigen, H.D.G.; Wynberg, E.; Verveen, A.; Dijkstra, M.; Verkaik, B.J.; Figaroa, O.J.A.; de Jong, M.C.; van der Veen, A.L.I.P.; Makowska, A.; Koedoot, N.; et al. One-fourth of COVID-19 patients have an impaired pulmonary function after 12 months of disease onset. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, M.; Benson, D.; Robison, S.; Raval, D.; Locy, M.L.; Patel, K.; Grumley, S.; Levitan, E.B.; Morris, P.; Might, M.; et al. Characteristics and Determinants of Pulmonary Long COVID. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e177518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Kanne, J.; Ashizawa, K.; Biederer, J.; Castañer, E.; Fan, L.; Frauenfelder, T.; Ghaye, B.; Henry, T.S.; Huang, Y.-S.; et al. Best Practice: International Multisociety Consensus Statement for Post-COVID-19 Residual Abnormalities on Chest CT Scans. Radiology 2025, 316, e243374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pulmonary Function Pattern | Diagnostic Criteria |

|---|---|

| Restrictive pattern | FVC < 80% predicted; TLC < 80% predicted; TLCO (DLCO single-breath) < 80% predicted; preserved FEV1 (≥65% predicted); FEV1/FVC ratio ≥ 70% |

| Obstructive pattern | FEV1 < 80% predicted; FEV1/FVC ratio < 70%; preserved lung volumes (TLC ≥ 80% predicted or FVC ≥ 80% predicted); TLCO < 80% predicted |

| Combined pattern | Obstructive physiology (FEV1 < 80% predicted and FEV1/FVC ratio < 70%) with reduced lung volumes (FVC < 80% predicted or TLC < 80% predicted) |

| Variables | N = 60 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) 1 | 60(13) |

| Gender 2 | |

| Female | 34 (57%) |

| Male | 26 (43%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) 1 | 32.4 (6.3) |

| Ethnicity 2 | |

| White | 24 (40%) |

| Black | 12 (20%) |

| Asian | 16 (27%) |

| Any other ethnic | 8 (13%) |

| Smoking status 2 | |

| Non-smoker | 40 (67%) |

| Ex-smoker | 18 (30%) |

| Smoker | 2 (3.3%) |

| Patient on medications 2 | 21(35%) |

| PFT | |

| Spirometry 1 | |

| FEV1 | 92 (21) |

| FVC | 94 (23) |

| VC | 92 (22) |

| FEV/VC | 102 (14) |

| PEF | 100 (23) |

| MMEF75/25 | 93 (44) |

| Lung volume 1 | |

| TLC | 86 (18) |

| ERV | 95 (52) |

| RV | 83 (25) |

| RV/TLC | 98 (19) |

| Diffusion capacity 1 | |

| TLCO SB | 83 (92) |

| VA Single Breath | 77 (17) |

| 1 Mean (SD); 2 n (%) | |

| Parameter | Percentage of Patients | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|

| FEV1 | 30.00% | p < 0.001 |

| FVC | 25.00% | p < 0.001 |

| FEV1/VC | 3.33% | p < 0.001 |

| TLC | 35.00% | p < 0.001 |

| TLCO | 75.00% | p < 0.001 |

| VC | 25.00% | p < 0.001 |

| Sensitivity Scenario | Normal, n (%) | Restrictive, n (%) | Obstructive, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FEV1/FVC < 70%, TLCO required | 53 (88.3) | 7 (11.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| FEV1/FVC < 75%, TLCO required | 53 (88.3) | 7 (11.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| FEV1/FVC < 70%, TLCO not required | 52 (86.7) | 7 (11.7) | 1 (1.7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Daodu, L.P.; Raste, Y.; Allgrove, J.E.; Arrigoni, F.I.F.; Kayyali, R. A Retrospective Observational Study of Pulmonary Impairments in Long COVID Patients. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010145

Daodu LP, Raste Y, Allgrove JE, Arrigoni FIF, Kayyali R. A Retrospective Observational Study of Pulmonary Impairments in Long COVID Patients. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010145

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaodu, Lanre Peter, Yogini Raste, Judith E. Allgrove, Francesca I. F. Arrigoni, and Reem Kayyali. 2026. "A Retrospective Observational Study of Pulmonary Impairments in Long COVID Patients" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010145

APA StyleDaodu, L. P., Raste, Y., Allgrove, J. E., Arrigoni, F. I. F., & Kayyali, R. (2026). A Retrospective Observational Study of Pulmonary Impairments in Long COVID Patients. Biomedicines, 14(1), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010145