Is Deep Remission the Right Time to De-Escalate Biologic Therapy in IBD? A Single-Center Retrospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Continuous use, of at least one year, of anti-TNF therapy (infliximab and adalimumab);

- Mucosal healing as an endoscopic finding at de-escalation;

- Discontinuation of therapy as a decision of the National Committee for Biologic Therapy due to achieving clinical and endoscopic remission.

- Exclusion criteria were as follows:

- Endoscopic and/or clinically active disease;

- Decision of the National Committee to continue therapy in addition to achieving mucosal healing after two years of treatment.

- Evaluation of disease activity:

- Endoscopic activity in patients with CD was evaluated by SES.

- Clinical activity in patients with UC was evaluated by the modified Truelove Witts score (MTWS):

- Endoscopic activity in patients with UC was evaluated by the Mayo sub-score.

- Clinical activity in patients with CD was evaluated by the CDAI score.

- Histological activity in patients with UC was evaluated by Nancy’s index.

- Histological activity in patients with CD was evaluated by GHAS (Global Histologic Disease Activity Score).

3. Statistics

4. Results (Patient Outcomes After Biologic De-Escalation)

- a.

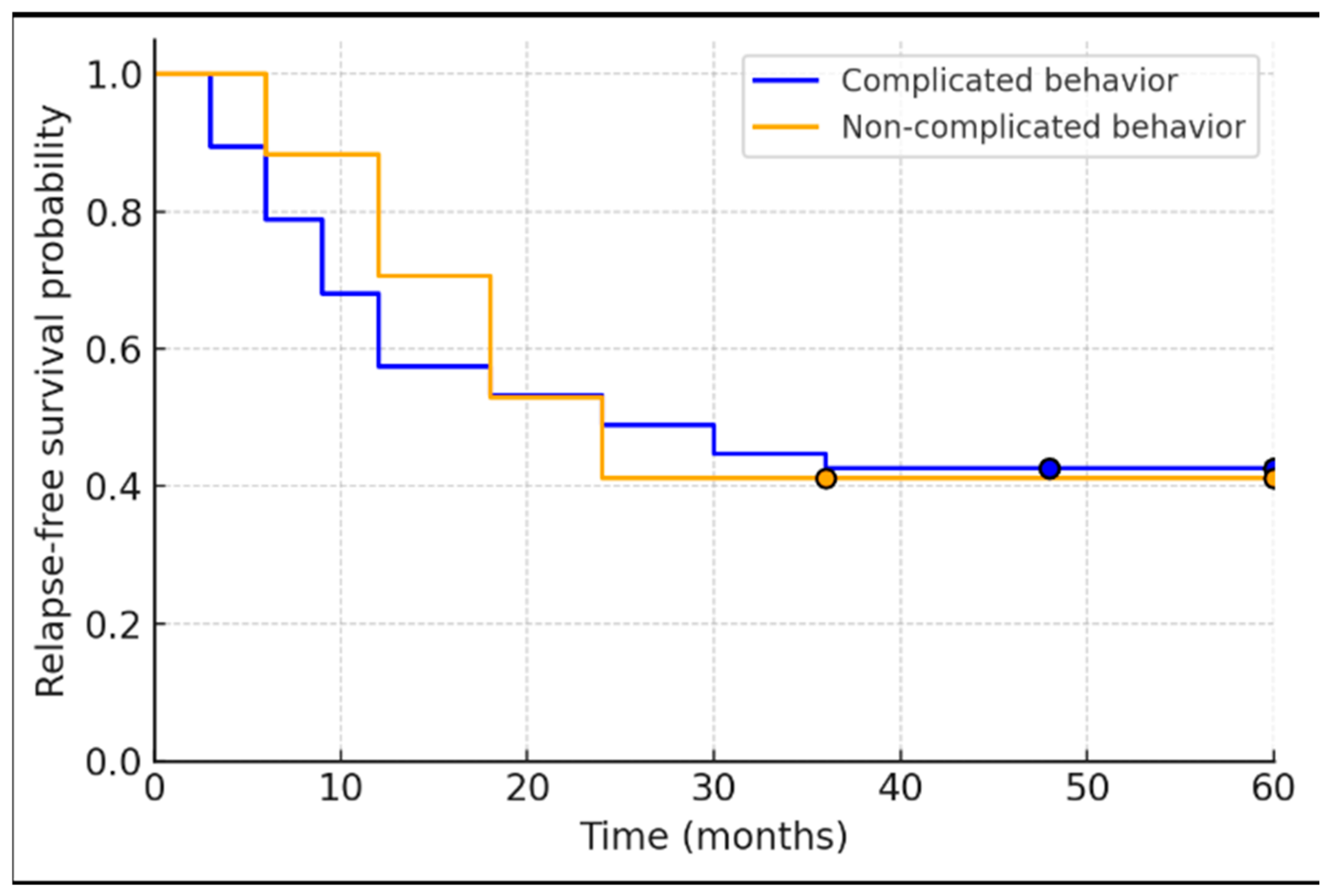

- Study Population and Baseline Characteristics: A total of 67 IBD patients met the initial inclusion criteria. Of these, 3 patients were excluded due to unavailable biopsy data, yielding 64 patients for analysis. Baseline demographic and disease characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The cohort included 25 UC patients (39.1%) and 39 CD patients (60.9%). The average age was 45 (SD ± 11.7) years, with 45.3% (29/64) of patients being male. The mean disease duration prior to de-escalation was 11.6 ± 8.3 years. All patients had been treated with anti-TNF therapy for a minimum of 24 months (by inclusion criteria) and had achieved endoscopic remission at the time of biologic withdrawal. The majority of patients (54.7%, 35/64) had received infliximab as their biologic, while 34.4% (22/64) had received adalimumab; a small subset (7.8%, 5/64) had been treated with both infliximab and adalimumab sequentially, and 3.1% (2/64) had been on a different advanced therapy (one on vedolizumab and one on a JAK inhibitor) prior to de-escalation. At the point of de-escalation, more than half of the patients—60.9% (39/64)—had achieved deep remission, defined as concurrent endoscopic and histological remission. After discontinuation of the biologic, 79.6% (51/64) of patients were maintained on immunomodulator therapy (thiopurine or methotrexate), whereas the remainder either received mesalamine only or no maintenance therapy. Among the 64 patients included in the cohort, 25 (39.1%) were diagnosed with ulcerative colitis (UC), the majority of whom (92%) presented with an extensive disease phenotype. The remaining 39 patients (60.9%) were diagnosed with Crohn’s disease (CD). Within the CD group, the most common disease location according to the Montreal classification was ileocolonic (L3), observed in 27 patients (69.2%), followed by colonic (L2) in 8 patients (20.5%), ileal (L1) in 4 patients (10.3%), and upper gastrointestinal involvement (L4) in 1 patient (2.5%). Regarding disease behavior, a stricturing phenotype (B2) was seen in 23 patients (58.9%), an inflammatory phenotype (B1) in 14 patients (35.8%), and a penetrating disease (B3) in 2 patients (5.1%). Additionally, perianal disease was documented in 9 patients (23.1%).

- b.

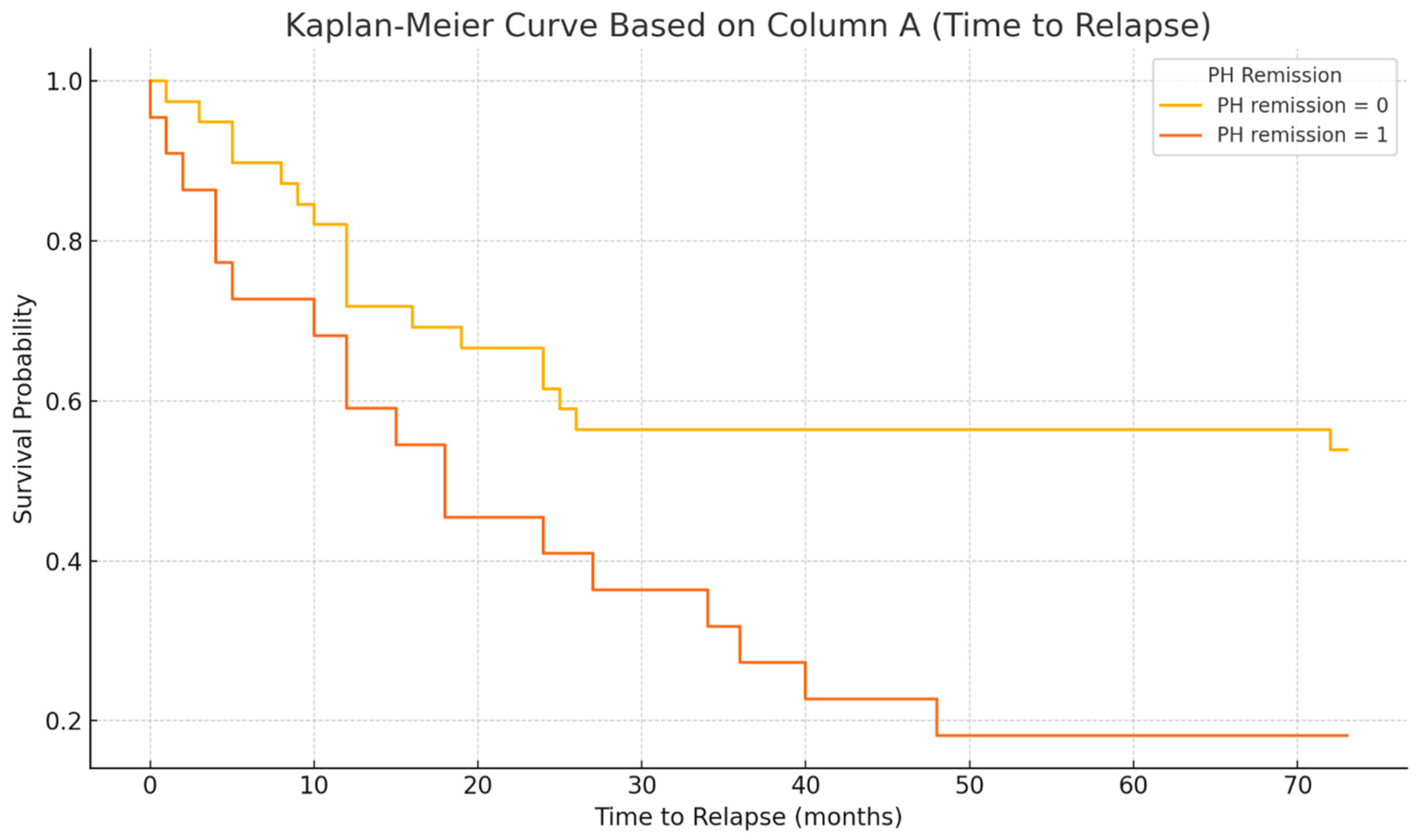

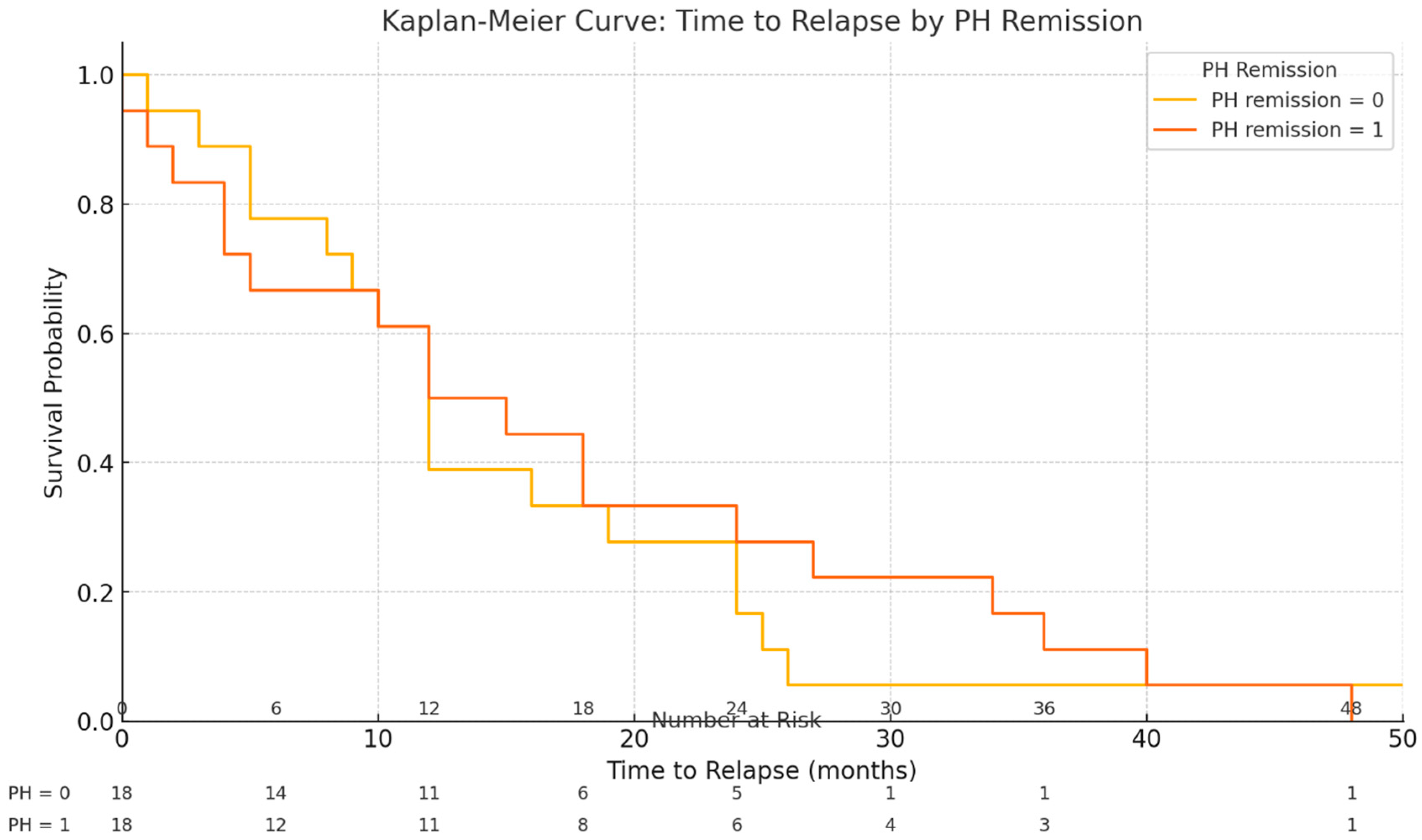

- Clinical Outcomes After Biologic Discontinuation: The median follow-up period after stopping the biologic therapy was 39 months (IQR 30–48 months). During this time, 57.8% of patients (37/64) experienced a clinical relapse of the disease (defined as recurrence of symptoms with objective inflammation requiring treatment re-initiation). The median time to relapse was 13.5 months (IQR 8–24 months) after biologic discontinuation (Table 2). Among the 37 patients who relapsed, 13.5% (5/37) were not receiving any maintenance therapy at the time of relapse, and an additional two ulcerative colitis patients (out of the 37 relapsers) were on mesalamine alone. The remaining 30 relapsing patients (30/37, 81.1%) had been on immunomodulator maintenance (azathioprine or methotrexate) when they relapsed. No significant differences were observed between patients who relapsed and those who remained in remission in terms of baseline age (p = 0.620), disease duration (p = 0.084), duration of anti-TNF therapy (p = 0.110), hemoglobin level (p = 0.323), or C-reactive protein (p = 0.424) at time of de-escalation.

- c.

- Biologic Re-Initiation and Treatment Responses

- d.

- Histological Activity and Relapse: Histological outcomes at baseline were strongly associated with relapse patterns. Among the 37 patients who relapsed, 18 patients (48.6%) had been in histologic remission at the time of biologic withdrawal, whereas the remaining 19 relapsers (51.4%) had signs of histological activity on their last biopsy despite endoscopic healing. Notably, all of these patients with baseline histologic activity were on immunomodulator maintenance therapy after de-escalation (i.e., histologic inflammation occurred despite concurrent IM). In contrast, of the 27 patients who did not experience relapse during the follow-up period, only 3 patients (11.1%) had residual histological activity at baseline. Two of those three non-relapsing patients with baseline histologic inflammation had not been on any maintenance therapy after biologic withdrawal (which may have contributed to their ongoing microscopic inflammation). Overall, histological remission was achieved in 65.6% of the cohort (42/64 patients) at the time of biologic cessation. There was a clear difference in outcomes: patients with any histological inflammation at withdrawal were more likely to relapse than those with complete histologic remission. We found a moderate positive correlation between the degree of histological activity (by histology scores) and the likelihood of relapse (Spearman’s rho = 0.467, p < 0.001). In a univariate analysis, the odds of relapse within the ~4-year follow-up were approximately 2.72-fold higher in patients with histologically active disease at baseline compared to those in histological remission. Stated differently, deep remission (combined endoscopic and histological remission) at the time of biologic discontinuation was associated with a more favorable course, whereas microscopic disease activity portended a higher risk of disease flare.

- e.

- Outcomes After Biologic Re-treatment (details regarding biologic therapy re-initiation and outcomes are provided in Table 3):

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Al-Bawardy, B.; Shivashankar, R.; Proctor, D.D. Novel and Emerging Therapies for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 651415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molander, P.; Kemppainen, H.; Ilus, T.; Sipponen, T. Long-term deep remission during maintenance therapy with biological agents in inflammatory bowel disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 55, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Gulati, A.; Alipour, O.; Shao, L. Relapse from deep remission after therapeutic de-escalation in inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Crohns Colitis 2020, 14, 1413–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, T.; Bonovas, S.; Burisch, J.; Kucharzik, T.; Adamina, M.; Annese, V.; Bachmann, O.; Bettenworth, D.; Chaparro, M.; Czuber-Dochan, W.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Ulcerative Colitis: Medical Treatment. J. Crohns Colitis 2022, 16, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.H.; Wu, R.C.; Kuo, C.J.; Chiu, H.Y.; Yeh, P.J.; Chen, C.M.; Chiu, C.T.; Tsou, Y.K.; Chang, C.W.; Pan, Y.B.; et al. Impact of complete histological remission on reducing flare-ups in moderate-to-severe, biologics-experienced ulcerative colitis patients with endoscopic remission. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2025, 124, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogler, G.; Vavricka, S.; Schoepfer, A.; Lakatos, P.L. Mucosal healing and deep remission: What does it mean? World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 7552–7560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gisbert, J.P.; Chaparro, M. De-escalation of Biologic Treatment in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Comprehensive Review. J. Crohns Colitis 2024, 18, 642–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frias Gomes, C.; Colombel, J.F.; Torres, J. De-escalation of Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2018, 20, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reenaers, C.; Mary, J.-Y.; Nachury, M.; Bouhnik, Y.; Laharie, D.; Allez, M.; Fumery, M.; Amiot, A.; Savoye, G.; Altwegg, R.; et al. Outcomes 7 Years After Infliximab Withdrawal for Patients With Crohn’s Disease in Sustained Remission. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 16, 234–243.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, D.H.W.; Tabatabavakili, S.; Shaffer, S.R.; Nguyen, G.C.; Weizman, A.V.; Targownik, L.E. Effectiveness of Dose De-escalation of Biologic Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 1768–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bots, S.J.; Kuin, S.; Ponsioen, C.Y.; Gecse, K.B.; Duijvestein, M.; D’Haens, G.R.; Löwenberg, M. Relapse rates and predictors for relapse in a real-life cohort of IBD patients after discontinuation of anti-TNF therapy. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 54, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, G.; Katsanos, K.H.; Burisch, J.; Allez, M.; Papamichael, K.; Stallmach, A.; Mao, R.; Berset, I.P.; Gisbert, J.P.; Sebastian, S.; et al. European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation Topical Review on Treatment Withdrawal (‘Exit Strategies’) in IBD. J. Crohns Colitis 2018, 12, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, E.D.; Siegel, C.A.; Chong, K.; Melmed, G.Y. Evaluating study withdrawal among biologics and immunomodulators in ulcerative colitis: A meta-analysis of trials. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 933–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, M.J.; Chaparro, M.; García-Sánchez, V.; Nantes, O.; Leo, E.; Rojas-Feria, M.; Jauregui-Amezaga, A.; García-López, S.; Huguet, J.M.; Arguelles-Arias, F.; et al. Evolution after anti-TNF discontinuation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A long-term follow-up study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 112, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, N.A.; Warner, B.; Johnston, E.L.; Flanders, L.; Hendy, P.; Ding, N.S.; Harris, R.; Fadra, A.S.; Basquill, C.; Lamb, C.A.; et al. Relapse after withdrawal from anti-TNF therapy for IBD: An observational study, plus systematic review and meta-analysis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 43, 910–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, R.; Boal, A.; Squires, S.I.; Lamb, C.; Clark, L.L.; Lamont, S.; Naismith, G. Optimising IBD patient selection for de-escalation of anti-TNF therapy to immunomodulator maintenance. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2020, 11, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, J. Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 765474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ni, R.S.; Daperno, M.; Scaglione, N.; Na, A.L.; Rocca, R.; Pera, A. Review article: Crohn’s disease: Monitoring disease activity. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003, 17, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Daperno, M.; Haens, G.D.; van Assche, G.; Baert, F. Development and validation of a new, simplified endoscopic activity score for Crohn’s disease: The SES-CD. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004, 60, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, R.V.; Winer, S.; Spl, T.; Riddell, R.H. Systematic review: Histological remission in inflammatory bowel disease. Is ‘complete’ remission the new treatment paradigm? An IOIBD initiative. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2014, 8, 1582–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mojtahed, A.; Khanna, R.; Sandborn, W.J.; D’Haensm, G.R.; Feagan, B.G.; Shackelton, L.M.; Baker, K.A.; Dubcenco, E.; Valasek, M.A.; Geboes, K.; et al. Assessment of Histologic Disease Activity in Crohn’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2014, 20, 2092–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchal-Bressenot, A.; Salleron, J.; Boulagnon-Rombi, C.; Bastien, C.; Cahn, V.; Cadiot, G.; Diebold, M.D.; Danese, S.; Reinisch, W.; Schreiber, S.; et al. Development and validation of the Nancy histological index for UC. Gut 2017, 66, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, E.; Mary, Y.; Vernier–Massouille, G.; Grimaud, J.-C.; Bouhnik, Y.; Laharie, D.; Dupas, J.-L.; Pillant, H.; Picon, L.; Veyrac, M.; et al. Maintenance of remission among patients with Crohn’s disease on antimetabolite therapy after infliximab therapy is stopped. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 63–70.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorino, G.; Cortes, P.N.; Ellul, P.; Felice, C.; Karatzas, P.; Silva, M.; Lakatos, P.L.; Bossa, F.; Ungar, B.; Sebastian, S.; et al. Discontinuation of Infliximab in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis is Associated with Increased Risk of Relapse: A Multinational Retrospective Cohort Study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 14, 1426–1432.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortlik, M.; Duricova, D.; Machkova, N.; Hruba, V.; Lukas, M.; Mitrova, K.; Romanko, I.; Bina, V.; Malickova, K.; Kolar, M.; et al. Discontinuation of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in inflammatory bowel disease patients: A prospective observation. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 51, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rismo, R.; Olsen, T.; Cui, G.; Paulssen, E.J.; Christiansen, I.; Johnsen, K.; Florholmen, J.; Goll, R. Normalization of mucosal cytokine gene expression levels predicts long-term remission after discontinuation of anti-TNF therapy in Crohn’s disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 48, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korelitz, B.I.; de Chambrun, P. Mucosal Healing as an Index of Colitis Activity: Back to Histological Healing for Future Indices. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2010, 16, 1628–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, L.; Nanda, K.S.; Zenlea, T.; Gifford, A.; Lawlor, G.O.; Falchuk, K.R.; Wolf, J.L.; Cheifetz, A.S.; Goldsmith, J.D.; Moss, A.C. Histologic markers of inflammation in patients with ulcerative colitis in clinical remission. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 991–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolford, D.D.; Fichera, A. Prophylaxis of Crohn’s disease recurrence: A surgeon’s perspective. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2020, 4, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Omidakhsh, N.; Bohn, R.L.; Thompson, J.S.; Brodovicz, K.G.; Deepak, P. Patients With Stricturing or Penetrating Crohn’s Disease Phenotypes Report High Disease Burden and Treatment Needs. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2023, 29, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pauwels, R.W.M.; van der Woude, C.J.; Nieboer, D.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Casanova, M.J.; Gisbert, J.P.; Kennedy, N.A.; Lees, C.W.; Louis, E.; Molnár, T.; et al. Prediction of Relapse After Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Cessation in Crohn’s Disease: Individual Participant Data Meta-analysis of 1317 Patients From 14 Studies. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 1671–1686.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Value (N = 64) |

|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 29 (45.3%) |

| Age (mean ± SD), years | 45.1 ± 11.8 |

| Disease duration (mean ± SD), years | 11.6 ± 8.3 |

| Diagnosis: Ulcerative colitis (UC) Extensive distal | 25 (39.1%) 23 (92%) 2 (8%) |

| Diagnosis: Crohn’s Disease (CD) L1 4 L2 8 L3 27 L4 1 B1 14 B2 23 B3 2 P 9 | 39 (60.9%) 4 (10.25%) 8 (20. 51%) 27 (69.2%) 1 (2.5%) 14 (35.8%) 23 (58.9%) 2 (5.1%) 9 (23.07%) |

| Biologic agent at withdrawal: Infliximab (anti-TNF) | 35 (54.7%) |

| Biologic agent: Adalimumab (anti-TNF) | 22 (34.4%) |

| Biologic agent: Sequential IFX → ADA | 5 (7.8%) |

| Biologic agent: Other (vedolizumab or JAK inhibitor) | 2 (3.1%) |

| Histological remission at withdrawal (deep remission) | 39 (60.9%) |

| On immunomodulator maintenance post-biologic, n (%) | 51 (79.7%) |

| Follow-Up Outcomes | Value |

|---|---|

| Follow-up duration, median (IQR) | 39.0 months (30–48) |

| Median time to relapse (among relapsers) | 13.5 months (8–24) |

| Maintained immunomodulator therapy | 51/64 patients (79.6%) |

| Patients with clinical relapse | 37/64 patients (57.8%) |

| No maintenance therapy at relapse | 5/37 relapsers (13.5%) |

| Mesalamine only at relapses (UC) | 2/37 relapsers (5.4%) |

| Immunomodulator at relapse (AZA/MTX) | 30/37 relapsers (81.1%) |

| Restart of Biologic Therapy | Patients (n) |

|---|---|

| Patients who restarted biologics after relapse | 34 |

| – Resumed the same anti-TNF agent | 27/34 (79.4%) |

| – Switched to a different anti-TNF (class swap) | 2/34 (5.9%) |

| – Switched to a different class (e.g., vedolizumab, ustekinumab) | 5/34 (14.7%) |

| Outcome after biologic re-initiation (subset analyzed, n = 18) | |

| – Achieved remission after restart | 15/18 (83.3%) |

| – Primary non-response (required surgery) | 2/18 (11.1%) |

| – Initial non-response but remission after switch within class | 1/18 (5.6%) |

| – Serious adverse event (e.g., anaphylaxis, psoriasis) | 2/18 (11.1%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Knezevic Ivanovski, T.; Perovic, M.M.; Stopic, B.; Golubovic, O.; Kralj, D.; Mitrovic, M.; Sreckovic, S.; Dobrosavljevic, A.; Svorcan, P.; Markovic, S. Is Deep Remission the Right Time to De-Escalate Biologic Therapy in IBD? A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1928. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13081928

Knezevic Ivanovski T, Perovic MM, Stopic B, Golubovic O, Kralj D, Mitrovic M, Sreckovic S, Dobrosavljevic A, Svorcan P, Markovic S. Is Deep Remission the Right Time to De-Escalate Biologic Therapy in IBD? A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(8):1928. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13081928

Chicago/Turabian StyleKnezevic Ivanovski, Tamara, Marija Milic Perovic, Bojan Stopic, Olga Golubovic, Djordje Kralj, Milos Mitrovic, Slobodan Sreckovic, Ana Dobrosavljevic, Petar Svorcan, and Srdjan Markovic. 2025. "Is Deep Remission the Right Time to De-Escalate Biologic Therapy in IBD? A Single-Center Retrospective Study" Biomedicines 13, no. 8: 1928. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13081928

APA StyleKnezevic Ivanovski, T., Perovic, M. M., Stopic, B., Golubovic, O., Kralj, D., Mitrovic, M., Sreckovic, S., Dobrosavljevic, A., Svorcan, P., & Markovic, S. (2025). Is Deep Remission the Right Time to De-Escalate Biologic Therapy in IBD? A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Biomedicines, 13(8), 1928. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13081928