Iron-Related Metabolic Targets in the Treatment of Osteosarcoma: Research Progress and Prospects

Abstract

1. Introduction

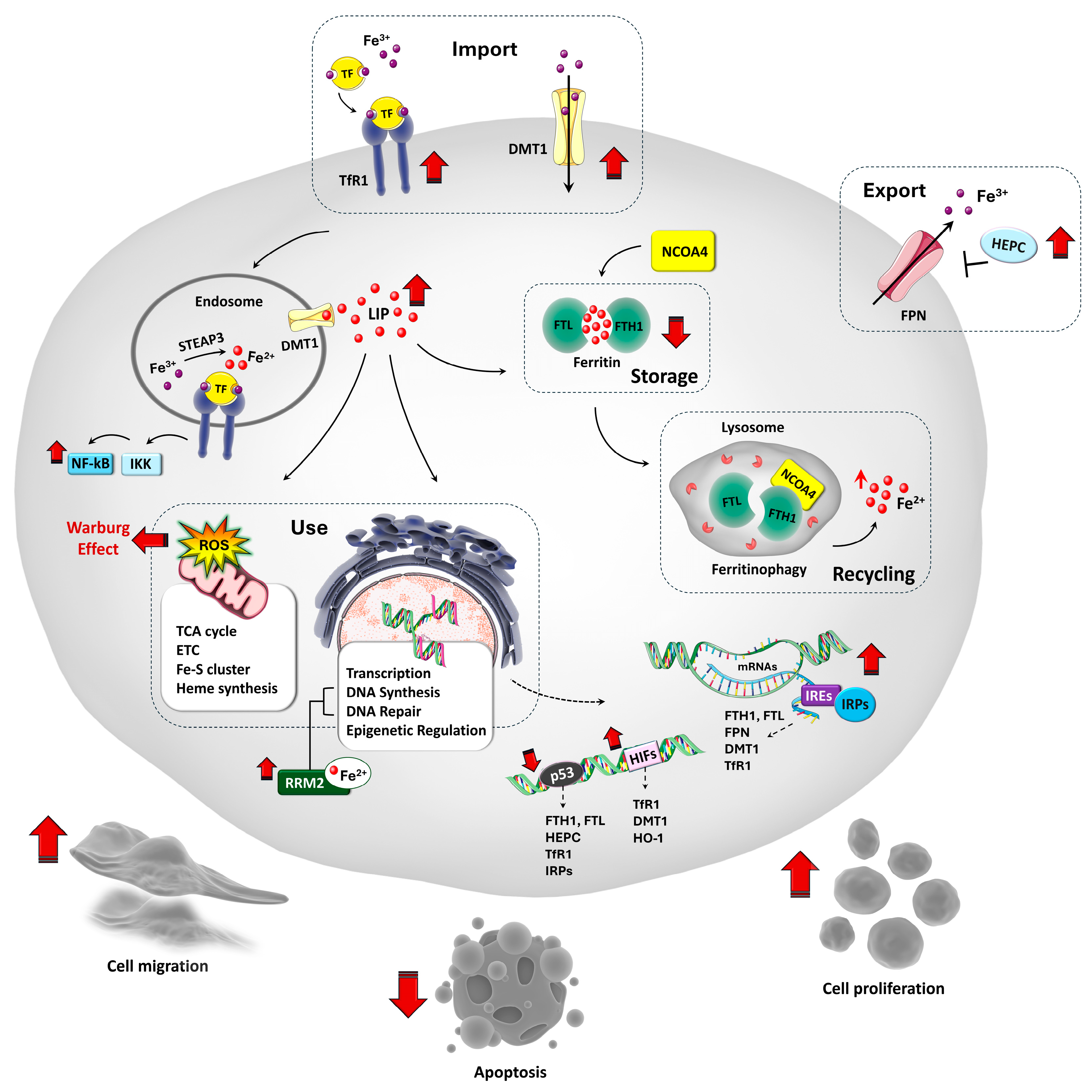

2. The Relevance of Iron in Cell Biology

3. Iron Homeostasis and Its Regulation in Physiological States

4. Iron Metabolism Dysregulation in OS

5. Manipulating Iron Homeostasis in OS

5.1. Targeting TfR1 for OS Therapy

5.2. Iron Chelation for OS Therapy

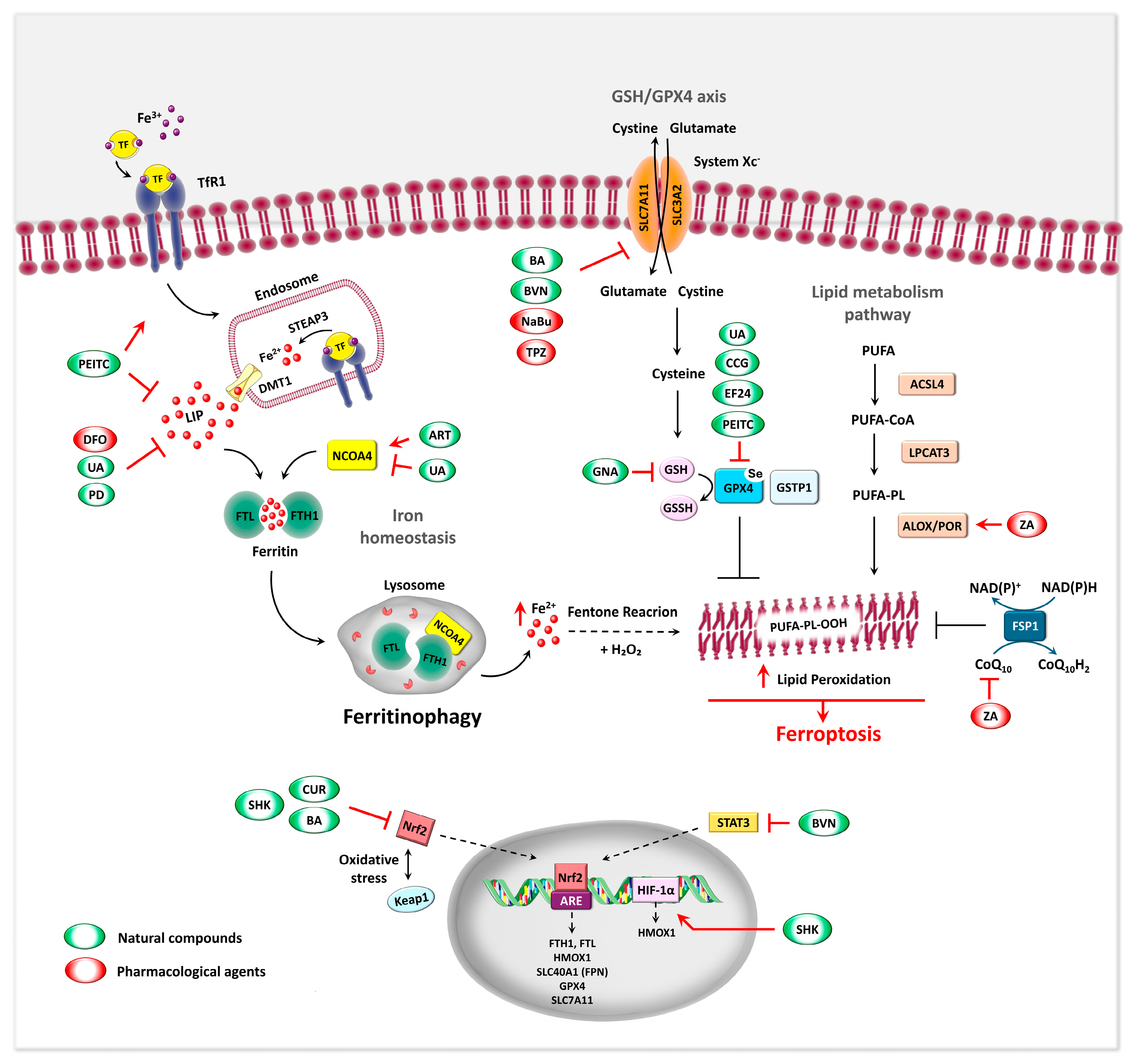

5.3. Ferroptosis as Iron-Related Metabolic Target in OS

5.3.1. Molecular Regulation and Morphological Features of Ferroptosis–General Aspects

5.3.2. Ferroptosis-Associated Markers in the Regulation of OS

5.3.3. Ferroptosis Inducers in OS

Natural Products Inducing Ferroptosis

| Compound | Cell Line/In Vivo Model | Concentrations | Combined Treatment | Molecular Mechanism | Observed Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bavachin | MG63, HOS | 5–80 μM | DFO, Fer-1, Lip-1, Vit E | ↓ SLC7A11 via STAT3 inhibition and P53 upregulation | ↑ Fe2+, ROS, LPO, ferroptosis | [155] |

| Baicalin | MG63, 143B/ xenograft | 60–120 μg/mL 200 mg/kg/day | Fer-1 | ↓ Nrf2 ↓ xCT GPX4 axis | ↑ ferroptosis, ↓ tumor growth | [156] |

| Curcumin | MG63, MNNG/HOS /xenograft | 22.5 μM | Lip-1, BM | ↓ Nrf2 ↓ GPX4 | ↑ ROS, ferroptosis, apoptosis ↓ tumor growth | [159] |

| EF24 | U2OS, SaOS-2 | 0.75–1.5 μM | Fer-1 | ↑ HMOX1 ↓ GPX4 | ↑ Fe2+, ROS, LPO ferroptosis | [154] |

| Gambogenic Acid | HOS, 143B/ xenograft | 0.25–8 μM 30 mg/kg/day | Fer-1, Eastin, NAC | ↑ P53, ↓SLC7A11, GPX4 | ↓ GSH, ↑ ROS, Mito dysfunction, ferroptosis and apoptosis ↓ tumor growth | [162] |

| β-Phenethyl isothiocyanate | MNNG/HOS, U-2OS, MG-63, 143B/xenograft | 30 μM 30 mg/kg/day | z-VAD-FMK, Ner-1, Fer-1, Lip-1, Baf-A1, 3-MA, NAC | ↑ TfR1, ↓ FTH1/FPN/DMT1 via MAPK, ↓ GPX4 | ↑ ferroptosis, apoptosis, autophagy ↓ tumor growth | [139] |

| Artesunate | MG63, 143B/ xenograft | 5–100 μM/ 200 mg/kg/day | Fer-1, DFO, 3-MA, Nec-1, NAC | ↑ TFR, DMT1, NCOA4, Mfrn2 ↓ GPX4, xCT | ↓ GSH, ↑ Fe2+, LPO ferroptosis, ferritinophagy, apoptosis ↓ tumor growth | [18] |

| Ursolic Acid | HOS, 143B/ xenograft | 35 μmol/L | DFO, CIS (20 μmol/L) | ↑ TFR, ↓ NCOA4, GPX4 | ↑ Fe2+, LPO ferroptosis, ferritinophagy, ↓ drug resistance ↓ tumor growth | [163] |

| Shikonin | MG63, HOS/ xenograft | 1 or 4 μM/ 2 mg/kg/day | Fer-1, DFO | ↑ HIF-1α/HO-1 → mito ROS | ↑ Fe2+, ROS, LPO, ferroptosis ↓tumor growth | [164] |

| MG63, 143B | 0.25–10 μM | Fer-1 | ↓ Nrf2 ↓ xCT GPX4 axis | ↑ Fe2+, ROS, LPO, ferroptosis | [165] | |

| Polydatin | SAOS-2, U2OS | 25–200 μM | Fer-1, NAC, DOX, CIS (10–20 µM) | ¯ | ↑ Fe2+, ROS, LPO, ↓ GSH, drug resistance | [151] |

| Curculigoside | HOS, U2OS, sjsa1, 143b/xenograft and mini-PDX | 50 and 75 μM/mL | Fer-1, DFO | ↑ TFR, ↓ GPX4, ↑ NF-κB, iNOS in macrophages | ↑ Fe2+, ROS, LPO, ferroptosis, apoptosis, maturation of RAW264.7 cells | [166] |

| Tirapazamine | 143B, MNNG/HOS, U2OS | 5–20 μM | Fer-1 | ↓ SLC7A11, GPX4 | ↑ Fe2+, ROS, ferroptosis under hypoxia | [167] |

| Sodium Butyrate | MNNG/HOS, U-2OS/xenograft | 0.5–2.5 mM | erastin | ↑ ATF3 ↓ SLC7A11 | ↑ LPO, erastin-induced ferroptosis, ↓ tumor growth | [168] |

| Zoledronic Acid | MG63, 143B/ xenograft | 2–16 μM/100 μg/kg | Lip-1, Z-VAD-FMK, Ner-1 | ↑ POR | ↑ ferroptosis ↓ tumor growth | [169] |

| U2OS, MNNG/HOS | 1–80 μM | Fer-1 | ↑ HMOX1, ↓ CoQ10 | ↑ LPO, ROS, ferroptosis | [170] |

Pharmacological Agents Inducing Ferroptosis

5.3.4. Nanomedicine Strategies to Promote Ferroptosis in OS

5.3.5. Genetic and RNA Biomarkers of Ferroptosis in the Regulation of OS

Ferroptosis-Related Genes in OS

Ferroptosis-Related ncRNA Networks in OS

5.4. Ferritinophagy: A Novel Target for OS Therapy

5.4.1. Ferritinophagy Regulatory Mechanism

5.4.2. Modulation of Ferritinophagy in OS: Emerging Therapeutic Approaches

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Muckenthaler, M.U.; Rivella, S.; Hentze, M.W.; Galy, B. A Red Carpet for Iron Metabolism. Cell 2017, 168, 344–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recalcati, S.; Gammella, E.; Buratti, P.; Cairo, G. Molecular regulation of cellular iron balance. IUBMB Life 2017, 69, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Wang, L. Iron metabolism and the tumor microenvironment: A new perspective on cancer intervention and therapy (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2024, 55, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, L.; Ding, J.; Chen, Y. Iron Metabolism in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 20, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, R.; Schreiber, S.L.; Conrad, M. Persister cancer cells: Iron addiction and vulnerability to ferroptosis. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 728–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, W.; Ferrara, N. Iron Metabolism in the Tumor Microenvironment: Contributions of Innate Immune Cells. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 626812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torti, S.V.; Torti, F.M. Iron: The cancer connection. Mol. Asp. Med. 2020, 75, 100860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.; Gianferante, D.M.; Zhu, B.; Mirabello, L. Osteosarcoma: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program-based analysis from 1975 to 2017. Cancer 2022, 128, 2107–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.A.; Hawkins, C.J. Recent and Ongoing Research into Metastatic Osteosarcoma Treatments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Li, R.; Li, J.; Lu, X.; Zhang, Y. The efficacy and safety comparison of first-line chemotherapeutic agents (high-dose methotrexate, doxorubicin, cisplatin, and ifosfamide) for osteosarcoma: A network meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. 2020, 15, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xie, L.; Ren, T.; Huang, Y.; Xu, J.; Guo, W. Immunotherapy for osteosarcoma: Fundamental mechanism, rationale, and recent breakthroughs. Cancer Lett. 2021, 500, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilienthal, I.; Herold, N. Targeting Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Treatment Efficacy and Resistance in Osteosarcoma: A Review of Current and Future Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badran, O.; Cohen, I.; Bar-Sela, G. The Impact of Iron on Cancer-Related Immune Functions in Oncology: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Evidence. Cancers 2024, 16, 4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, S.; Wang, S.; Lv, H.; Zhou, L.; Shang, P. Iron Chelator Induces Apoptosis in Osteosarcoma Cells by Disrupting Intracellular Iron Homeostasis and Activating the MAPK Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelaria, P.V.; Leoh, L.S.; Penichet, M.L.; Daniels-Wells, T.R. Antibodies Targeting the Transferrin Receptor 1 (TfR1) as Direct Anti-cancer Agents. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 607692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vico, G.; Martano, M.; Maiolino, P.; Carella, F.; Leonardi, L. Expression of transferrin receptor-1 (TFR-1) in canine osteosarcomas. Vet. Med. Sci. 2020, 6, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Cong, L.; Shen, W.; Yang, C.; Ye, K. Ferroptosis defense mechanisms: The future and hope for treating osteosarcoma. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2024, 42, e4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Xu, R.; Shi, J.; Yang, Z.; Zheng, J.; Wei, D. Artesunate induces ferroptosis in osteosarcoma through NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2025, 39, e70488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, K.; Leandri, R.; Federico, G.; De Vico, G.; Leonardi, L. Ferritinophagy: A possible new iron-related metabolic target in canine osteoblastic osteosarcoma. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1546872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreini, C.; Putignano, V.; Rosato, A.; Banci, L. The human iron-proteome. Met. Integr. Biometal Sci. 2018, 10, 1223–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, S.J.F.; Woolf, C.J.; Weiss, G.; Penninger, J.M. The Role of Iron Regulation in Immunometabolism and Immune-Related Disease. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2019, 6, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, M.R.; Armitage, A.E.; Drakesmith, H. Why cells need iron: A compendium of iron utilisation. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 35, 1026–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganz, T. Systemic iron homeostasis. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 1721–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskenkorva-Frank, T.S.; Weiss, G.; Koppenol, W.H.; Burckhardt, S. The complex interplay of iron metabolism, reactive oxygen species, and reactive nitrogen species: Insights into the potential of various iron therapies to induce oxidative and nitrosative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 65, 1174–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantopoulos, K.; Porwal, S.K.; Tartakoff, A.; Devireddy, L. Mechanisms of mammalian iron homeostasis. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 5705–5724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardi, C.; Arezzini, B.; Fortino, V.; Comporti, M. Effect of free iron on collagen synthesis, cell proliferation and MMP-2 expression in rat hepatic stellate cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002, 64, 1139–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, S.; Hamza, I.; Bartnikas, T.B. Molecular Mechanisms of Iron and Heme Metabolism. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2022, 42, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.-L.; Ghosh, M.C.; Rouault, T.A. The physiological functions of iron regulatory proteins in iron homeostasis—An update. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koleini, N.; Shapiro, J.S.; Geier, J.; Ardehali, H. Ironing out mechanisms of iron homeostasis and disorders of iron deficiency. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e148671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C.P.; Shen, M.; Eisenstein, R.S.; Leibold, E.A. Mammalian iron metabolism and its control by iron regulatory proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Mol. Cell Res. 2012, 1823, 1468–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philpott, C.C.; Protchenko, O.; Wang, Y.; Novoa-Aponte, L.; Leon-Torres, A.; Grounds, S.; Tietgens, A.J. Iron-tracking strategies: Chaperones capture iron in the cytosolic labile iron pool. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1127690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoelzgen, F.; Nguyen, T.T.P.; Klukin, E.; Boumaiza, M.; Srivastava, A.K.; Kim, E.Y.; Zalk, R.; Shahar, A.; Cohen-Schwartz, S.; Meyron-Holtz, E.G.; et al. Structural basis for the intracellular regulation of ferritin degradation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes-Hampton, G.P.; Ghosh, M.C.; Rouault, T.A. Methods for Studying Iron Regulatory Protein 1: An Important Protein in Human Iron Metabolism. Methods Enzymol. 2018, 599, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.M.; Lee, J.; Finley, L.W.S.; Schmidt, P.J.; Fleming, M.D.; Haigis, M.C. SIRT3 regulates cellular iron metabolism and cancer growth by repressing iron regulatory protein 1. Oncogene 2015, 34, 2115–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazawa, M.; Bogdan, A.R.; Hashimoto, K.; Tsuji, Y. Regulation of transferrin receptor-1 mRNA by the interplay between IRE-binding proteins and miR-7/miR-141 in the 3′-IRE stem–loops. RNA 2018, 24, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camaschella, C.; Nai, A.; Silvestri, L. Iron metabolism and iron disorders revisited in the hepcidin era. Haematologica 2020, 105, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, E.; Tuttle, M.S.; Powelson, J.; Vaughn, M.B.; Donovan, A.; Ward, D.M.V.; Ganz, T.; Kaplan, J. Hepcidin Regulates Cellular Iron Efflux by Binding to Ferroportin and Inducing Its Internalization. Science 2004, 306, 2090–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemeth, E.; Ganz, T. Hepcidin-Ferroportin Interaction Controls Systemic Iron Homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowdley, K.V.; Gochanour, E.M.; Sundaram, V.; Shah, R.A.; Handa, P. Hepcidin Signaling in Health and Disease: Ironing Out the Details. Hepatol. Commun. 2021, 5, 723–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Alfaro-Magallanes, V.M.; Babitt, J.L. Bone morphogenic proteins in iron homeostasis. Bone 2020, 138, 115495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masoud, G.N.; Li, W. HIF-1α pathway: Role, regulation and intervention for cancer therapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2015, 5, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Y.M.; Xie, L. Hypoxia-inducible factors link iron homeostasis and erythropoiesis. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyssonnaux, C.; Zinkernagel, A.S.; Schuepbach, R.A.; Rankin, E.; Vaulont, S.; Haase, V.H.; Nizet, V.; Johnson, R.S. Regulation of iron homeostasis by the hypoxia-inducible transcription factors (HIFs). J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 1926–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slominski, R.M.; Raman, C.; Chen, J.Y.; Slominski, A.T. How cancer hijacks the body’s homeostasis through the neuroendocrine system. Trends Neurosci. 2023, 46, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Yang, W.; Liu, J.; Zhang, F. Interleukin-6 upregulates SOX18 expression in osteosarcoma. OncoTargets Ther. 2017, 10, 5329–5336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czarnecka, A.M.; Synoradzki, K.; Firlej, W.; Bartnik, E.; Sobczuk, P.; Fiedorowicz, M.; Grieb, P.; Rutkowski, P. Molecular Biology of Osteosarcoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Gong, J.; Sheng, S.; Lu, M.; Guo, S.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Tian, Z.; Tian, Y. Increased hepcidin in hemorrhagic plaques correlates with iron-stimulated IL-6/STAT3 pathway activation in macrophages. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 515, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela, D.; Vela-Gaxha, Z. Differential regulation of hepcidin in cancer and non-cancer tissues and its clinical implications. Exp. Mol. Med. 2018, 50, e436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, F.; Tuffour, A.; Hao, G.; Peprah, F.A.; Huang, A.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H. Distinctive modulation of hepcidin in cancer and its therapeutic relevance. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1141603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinnix, Z.K.; Miller, L.D.; Wang, W.; D’AGostino, R.; Kute, T.; Willingham, M.C.; Hatcher, H.; Tesfay, L.; Sui, G.; Di, X.; et al. Ferroportin and Iron Regulation in Breast Cancer Progression and Prognosis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2010, 2, 43ra56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, X.; Mu, Y.; Lu, C.; Tang, S.; Lu, K.; Qiu, X.; Wei, A.; Cheng, Y.; Wei, W. The iron chelator desferrioxamine synergizes with chemotherapy for cancer treatment. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2019, 56, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joachim, J.H.; Mehta, K.J. Hepcidin in hepatocellular carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2022, 127, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Zhou, J.; Su, Y.; Yang, Q.; Li, J. TFRC promotes the proliferation, migration, and invasion of osteosarcoma cells by increasing the intracellular iron content and RRM2 expression. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1567216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, J.; Dai, R.; Xu, J.; Feng, H. Transferrin receptor-1 and VEGF are prognostic factors for osteosarcoma. J. Orthop. Surg. 2019, 14, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenneth, N.S.; Mudie, S.; Naron, S.; Rocha, S. TfR1 interacts with the IKK complex and is involved in IKK-NF-κB signalling. Biochem. J. 2013, 449, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Y.; Guo, W.; Ling, J.; Xu, D.; Liao, Y.; Zhao, H.; Du, X.; Wang, H.; Xu, M.; Song, H.; et al. Iron-dependent CDK1 activity promotes lung carcinogenesis via activation of the GP130/STAT3 signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, S.; Kuang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Yu, B. Mitochondrion-mediated iron accumulation promotes carcinogenesis and Warburg effect through reactive oxygen species in osteosarcoma. Cancer Cell Int. 2020, 20, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.; Xue, X. Targeting iron metabolism in cancer therapy. Theranostics 2021, 11, 8412–8429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Zheng, A.; Chen, L.; Dang, F.; Liu, X.; Gao, J. Benzo(a)pyrene affects proliferation with reference to metabolic genes and ROS/HIF-1α/HO-1 signaling in A549 and MCF-7 cancer cells. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 45, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Wang, D.; Li, N. MicroRNA-20b Downregulates HIF-1α and Inhibits the Proliferation and Invasion of Osteosarcoma Cells. Oncol. Res. 2016, 23, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renassia, C.; Peyssonnaux, C. New insights into the links between hypoxia and iron homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2019, 26, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, M.; Huang, E.; Chen, X. Iron regulatory protein 2 is a suppressor of mutant p53 in tumorigenesis. Oncogene 2019, 38, 6256–6269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weizer-Stern, O.; Adamsky, K.; Margalit, O.; Ashur-Fabian, O.; Givol, D.; Amariglio, N.; Rechavi, G. Hepcidin, a key regulator of iron metabolism, is transcriptionally activated by p53. Br. J. Haematol. 2007, 138, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, W.; Tsuji, Y.; Torti, S.V.; Torti, F.M. Post-transcriptional modulation of iron homeostasis during p53-dependent growth arrest. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 33911–33918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G.-H.; Fu, L.; Chen, J.; Wei, F.; Shi, W.-X. Decreased expression of ferritin light chain in osteosarcoma and its correlation with epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 2580–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, W.; Razak, S.R.A.; Han, T.; Ahmad, N.H.; Li, X. Ferroptosis as a potential target for cancer therapy. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, R.; Liao, L.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Cai, S.; Miao, X.; Li, T.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Q.; Cheng, X.; et al. Downregulation of ferroptosis-related Genes can regulate the invasion and migration of osteosarcoma cells. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhao, J.; Feng, H. Targeting iron metabolism in osteosarcoma. Discov. Oncol. 2023, 14, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorella, S.; Karagiannis, T.C. Transferrin Receptor-Mediated Endocytosis: A Useful Target for Cancer Therapy. J. Membr. Biol. 2014, 247, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Fan, K.; Wang, L.; Ying, X.; Sanders, A.J.; Guo, T.; Xing, X.; Zhou, M.; Du, H.; Hu, Y.; et al. TfR1 binding with H-ferritin nanocarrier achieves prognostic diagnosis and enhances the therapeutic efficacy in clinical gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, B.; Connor, J.R. Emerging and Dynamic Biomedical Uses of Ferritin. Pharmaceuticals 2018, 11, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, T.R.; Bernabeu, E.; Rodríguez, J.A.; Patel, S.; Kozman, M.; Chiappetta, D.A.; Holler, E.; Ljubimova, J.Y.; Helguera, G.; Penichet, M.L. The transferrin receptor and the targeted delivery of therapeutic agents against cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1820, 291–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songbo, M.; Lang, H.; Xinyong, C.; Bin, X.; Ping, Z.; Liang, S. Oxidative stress injury in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Toxicol. Lett. 2019, 307, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almagro, J.C.; Daniels-Wells, T.R.; Perez-Tapia, S.M.; Penichet, M.L. Progress and Challenges in the Design and Clinical Development of Antibodies for Cancer Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.P.; Helguera, G.; Daniels, T.R.; Lomas, S.Z.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Schiller, G.; Bonavida, B.; Morrison, S.L.; Penichet, M.L. Molecular events contributing to cell death in malignant human hematopoietic cells elicited by an IgG3-avidin fusion protein targeting the transferrin receptor. Blood 2006, 108, 2745–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, T.R.; Ortiz-Sánchez, E.; Luria-Pérez, R.; Quintero, R.; Helguera, G.; Bonavida, B.; Martínez-Maza, O.; Penichet, M.L. An Antibody-based Multifaceted Approach Targeting the Human Transferrin Receptor for the Treatment of B-cell Malignancies. J. Immunother. 2011, 34, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels-Wells, T.R.; Widney, D.P.; Leoh, L.S.; Martínez-Maza, O.; Penichet, M.L. Efficacy of an Anti-transferrin Receptor 1 Antibody Against AIDS-related Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Brief Communication. J. Immunother. 2015, 38, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neiveyans, M.; Melhem, R.; Arnoult, C.; Bourquard, T.; Jarlier, M.; Busson, M.; Laroche, A.; Cerutti, M.; Pugnière, M.; Ternant, D.; et al. A recycling anti-transferrin receptor-1 monoclonal antibody as an efficient therapy for erythroleukemia through target up-regulation and antibody-dependent cytotoxic effector functions. mAbs 2019, 11, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakase, M.; Inui, M.; Okumura, K.; Kamei, T.; Nakamura, S.; Tagawa, T. p53 gene therapy of human osteosarcoma using a transferrin-modified cationic liposome. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2005, 4, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford, M.R.; Ford, S.J.; Horniblow, R.D.; Iqbal, T.H.; Tselepis, C. Iron chelation in the treatment of cancer: A new role for deferasirox? J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 53, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tury, S.; Assayag, F.; Bonin, F.; Chateau-Joubert, S.; Servely, J.; Vacher, S.; Becette, V.; Caly, M.; Rapinat, A.; Gentien, D.; et al. The iron chelator deferasirox synergises with chemotherapy to treat triple-negative breast cancers. J. Pathol. 2018, 246, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.-H.; Jeong, J.-K.; Park, S.-Y. Deferoxamine inhibits TRAIL-mediated apoptosis via regulation of autophagy in human colon cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 33, 1171–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.L.; Lee, D.-H.; Na, Y.J.; Kim, B.R.; Jeong, Y.A.; Lee, S.I.; Kang, S.; Joung, S.Y.; Lee, S.-Y.; Oh, S.C.; et al. Iron chelator-induced apoptosis via the ER stress pathway in gastric cancer cells. Tumour Biol. J. Int. Soc. OncoDev. Biol. Med. 2016, 37, 9709–9719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wang, S.; Liu, P. Deferoxamine Enhanced Mitochondrial Iron Accumulation and Promoted Cell Migration in Triple-Negative MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Cells Via a ROS-Dependent Mechanism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rensvold, J.W.; Ong, S.-E.; Jeevananthan, A.; Carr, S.A.; Mootha, V.K.; Pagliarini, D.J. Complementary RNA and Protein Profiling Identifies Iron as a Key Regulator of Mitochondrial Biogenesis. Cell Rep. 2013, 3, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Zheng, X.; Shou, K.; Niu, Y.; Jian, C.; Zhao, Y.; Yi, W.; Hu, X.; Yu, A. The iron chelator Dp44mT suppresses osteosarcoma’s proliferation, invasion and migration: In vitro and in vivo. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2016, 8, 5370–5385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Argenziano, M.; Di Paola, A.; Tortora, C.; Di Pinto, D.; Pota, E.; Di Martino, M.; Perrotta, S.; Rossi, F.; Punzo, F. Effects of Iron Chelation in Osteosarcoma. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2021, 21, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Niu, X.; Wang, Z.; Song, C.-L.; Huang, Z.; Chen, K.-N.; Duan, J.; Bai, H.; Xu, J.; Zhao, J.; et al. Multiregion Sequencing Reveals the Genetic Heterogeneity and Evolutionary History of Osteosarcoma and Matched Pulmonary Metastases. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, O.; O’Sullivan, J. Iron chelators in cancer therapy. BioMetals 2020, 33, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitnall, M.; Howard, J.; Ponka, P.; Richardson, D.R. A class of iron chelators with a wide spectrum of potent antitumor activity that overcomes resistance to chemotherapeutics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 14901–14906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, G.; Zhuang, L.; Gan, B. Targeting ferroptosis as a vulnerability in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2022, 22, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, F.; Liao, M.; Qin, R.; Zhu, S.; Peng, C.; Fu, L.; Chen, Y.; Han, B. Regulated cell death (RCD) in cancer: Key pathways and targeted therapies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, X.; Jin, S.; Chen, Y.; Guo, R. Ferroptosis in cancer therapy: A novel approach to reversing drug resistance. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, E.; Chen, X.; Linkermann, A.; Jiang, X.; Kang, R.; Kagan, V.E.; Bayir, H.; Yang, W.S.; Garcia-Saez, A.J.; Ioannou, M.S.; et al. A guideline on the molecular ecosystem regulating ferroptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2024, 26, 1447–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coradduzza, D.; Congiargiu, A.; Chen, Z.; Zinellu, A.; Carru, C.; Medici, S. Ferroptosis and Senescence: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Loenhout, J.; Peeters, M.; Bogaerts, A.; Smits, E.; Deben, C. Oxidative Stress-Inducing Anticancer Therapies: Taking a Closer Look at Their Immunomodulating Effects. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Shen, G.; Fan, M.; Zheng, P. Lipid metabolic reprogramming and associated ferroptosis in osteosarcoma: From molecular mechanisms to potential targets. J. Bone Oncol. 2025, 51, 100660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, G.; Alloisio, G.; Lelli, V.; Marini, S.; Rinalducci, S.; Gioia, M. Mechano-induced cell metabolism disrupts the oxidative stress homeostasis of SAOS-2 osteosarcoma cells. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1297826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yan, Q.; Wang, Z.; Hu, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Gao, X.; Bai, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; et al. Ferroptosis and its implications in bone-related diseases. PeerJ 2024, 12, e18626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Dou, Y.; Xia, R.; Liu, S.; Fu, J.; Li, D.; Wang, R.; Tie, F.; Li, L.; Jin, H.; et al. Research progress on the role of lncRNA, circular RNA, and microRNA networks in regulating ferroptosis in osteosarcoma. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 176, 116924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Su, Y.; Xu, K.; Zheng, H.; Yuan, Q.; Cai, Y.; Aihaiti, Y.; Xu, P. Ferroptosis-related lncRNAs guiding osteosarcoma prognosis and immune microenvironment. J. Orthop. Surg. 2023, 18, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Tang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, G.; Jiang, X.; Mo, Y.; Wu, P.; Deng, X.; Li, L.; Zuo, S.; et al. Regulatory pathways and drugs associated with ferroptosis in tumors. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, P.; Roth, M.E.; Gill, J.; Piperdi, S.; Chinai, J.M.; Geller, D.S.; Hoang, B.H.; Park, A.; Fremed, M.A.; Zang, X.; et al. Immune infiltration and PD-L1 expression in the tumor microenvironment are prognostic in osteosarcoma. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, P.; Roth, M.E.; Gill, J.; Chinai, J.M.; Ewart, M.R.; Piperdi, S.; Geller, D.S.; Hoang, B.H.; Fatakhova, Y.V.; Ghorpade, M.; et al. HHLA2, a member of the B7 family, is expressed in human osteosarcoma and is associated with metastases and worse survival. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, F.; Lu, G.-H.; Nie, W.; Zhang, L.; Lv, Y.; Bao, W.; Gao, X.; Wei, W.; Pu, K.; et al. Engineering Magnetosomes for Ferroptosis/Immunomodulation Synergism in Cancer. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 5662–5673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf-Dennen, K.; Gordon, N.; Kleinerman, E.S. Exosomal communication by metastatic osteosarcoma cells modulates alveolar macrophages to an M2 tumor-promoting phenotype and inhibits tumoricidal functions. OncoImmunology 2020, 9, 1747677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Aabed, N.; Shah, Y.M. Reactive Oxygen Species and Ferroptosis at the Nexus of Inflammation and Colon Cancer. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2023, 39, 551–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, D.; Chen, X.; Kroemer, G. Cuproptosis: A copper-triggered modality of mitochondrial cell death. Cell Res. 2022, 32, 417–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, B.R.; Jiang, X. The Chemistry and Biology of Ferroptosis. Cell Chem. Biol. 2020, 27, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursini, F.; Maiorino, M. Lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis: The role of GSH and GPx4. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 152, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Kang, R.; Klionsky, D.J.; Tang, D. GPX4 in cell death, autophagy, and disease. Autophagy 2023, 19, 2621–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J.; Patel, D.N.; Welsch, M.; Skouta, R.; Lee, E.D.; Hayano, M.; Thomas, A.G.; Gleason, C.E.; Tatonetti, N.P.; Slusher, B.S.; et al. Pharmacological inhibition of cystine–glutamate exchange induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis. eLife 2014, 3, e02523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.-R.; Zhu, W.-T.; Pei, D.-S. System Xc-: A key regulatory target of ferroptosis in cancer. Invest. New Drugs 2021, 39, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Wang, W.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Yu, X.; Tu, J.; Zhang, Z. Ferroptosis: A New Regulatory Mechanism in Osteoporosis. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 2634431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anandhan, A.; Dodson, M.; Schmidlin, C.J.; Liu, P.; Zhang, D.D. Breakdown of an Ironclad Defense System: The Critical Role of NRF2 in Mediating Ferroptosis. Cell Chem. Biol. 2020, 27, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellezza, I.; Giambanco, I.; Minelli, A.; Donato, R. Nrf2-Keap1 signaling in oxidative and reductive stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2018, 1865, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, K. The induction of ferroptosis by impairing STAT3/Nrf2/GPx4 signaling enhances the sensitivity of osteosarcoma cells to cisplatin. Cell Biol. Int. 2019, 43, 1245–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, Y. The interaction between ferroptosis and lipid metabolism in cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, X.; Green, M.D.; Wang, W.; Yu, J.; Choi, J.E.; Jiang, L.; Liao, P.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Q.; Dow, A.; et al. Radiotherapy and Immunotherapy Promote Tumoral Lipid Oxidation and Ferroptosis via Synergistic Repression of SLC7A11. Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 1673–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhu, T.; Wang, X.; Xiong, F.; Hu, Z.; Qiao, X.; Yuan, X.; Wang, D. ACSL3 and ACSL4, Distinct Roles in Ferroptosis and Cancers. Cancers 2022, 14, 5896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, F.; Liu, J.; Tang, D.; Kang, R. Oxidative Damage and Antioxidant Defense in Ferroptosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 586578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.; Zhang, M.; Luo, C.; Wei, P.; Cui, K.; Chen, Z. Targeting Ferroptosis Attenuates Inflammation, Fibrosis, and Mast Cell Activation in Chronic Prostatitis. J. Immunol. Res. 2022, 2022, 6833867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Dai, J.; Hou, G.; Liu, H.; Zheng, S.; Wang, X.; Lin, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, M.; Gong, Y.; et al. SMURF2 predisposes cancer cell toward ferroptosis in GPX4-independent manners by promoting GSTP1 degradation. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 4352–4369.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zuo, M.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, X. Glutathione S-transferase-Pi 1 protects cells from irradiation-induced death by inhibiting ferroptosis in pancreatic cancer. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2024, 38, e70033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, F.; Chen, F.; Chen, S.; Wang, B.; Liu, J.; Shao, Z. Association between GSTP1 polymorphisms and prognosis of osteosarcoma in patients treated with chemotherapy: A meta-analysis. OncoTargets Ther. 2015, 8, 1835–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnova, Y.D.; Hanetseder, D.; Derigo, L.; Gasser, A.S.; Vaglio-Garro, A.; Sperger, S.; Brunauer, R.; Korneeva, O.S.; Duvigneau, J.C.; Presen, D.M.; et al. Osteosarcoma Cells and Undifferentiated Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Are More Susceptible to Ferroptosis than Differentiated Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Karakhanova, S.; Hartwig, W.; D’HAese, J.G.; Philippov, P.P.; Werner, J.; Bazhin, A.V. Mitochondria and Mitochondrial ROS in Cancer: Novel Targets for Anticancer Therapy. J. Cell. Physiol. 2016, 231, 2570–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppula, P.; Lei, G.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Mao, C.; Kondiparthi, L.; Shi, J.; Liu, X.; Horbath, A.; Das, M.; et al. A targetable CoQ-FSP1 axis drives ferroptosis- and radiation-resistance in KEAP1 inactive lung cancers. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panczyszyn, E.; Saverio, V.; Monzani, R.; Gagliardi, M.; Petrovic, J.; Stojkovska, J.; Collavin, L.; Corazzari, M. FSP1 is a predictive biomarker of osteosarcoma cells’ susceptibility to ferroptotic cell death and a potential therapeutic target. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Comish, P.B.; Tang, D.; Kang, R. Characteristics and Biomarkers of Ferroptosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 637162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Chen, X.; Kang, R.; Kroemer, G. Ferroptosis: Molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell Res. 2021, 31, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Liu, T.; Luo, D.; Luan, D.; Cheng, L.; Wang, S. Novel Therapeutic Savior for Osteosarcoma: The Endorsement of Ferroptosis. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 746030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isani, G.; Bertocchi, M.; Andreani, G.; Farruggia, G.; Cappadone, C.; Salaroli, R.; Forni, M.; Bernardini, C. Cytotoxic Effects of Artemisia annua L. and Pure Artemisinin on the D-17 Canine Osteosarcoma Cell Line. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 1615758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guanizo, A.C.; Fernando, C.D.; Garama, D.J.; Gough, D.J. STAT3: A multifaceted oncoprotein. Growth Factors 2018, 36, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liao, S.; Bennett, S.; Tang, H.; Song, D.; Wood, D.; Zhan, X.; Xu, J. STAT3 and its targeting inhibitors in osteosarcoma. Cell Prolif. 2021, 54, e12974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, D.; Kim, E.H.; Lee, J.; Roh, J.-L. Nrf2 inhibition reverses resistance to GPX4 inhibitor-induced ferroptosis in head and neck cancer. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 129, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Li, T.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Wang, W.; Fu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Hao, Y. Activatable nanomedicine for overcoming hypoxia-induced resistance to chemotherapy and inhibiting tumor growth by inducing collaborative apoptosis and ferroptosis in solid tumors. Biomaterials 2021, 268, 120537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, H.-H.; Zhen, C.-X.; Liu, J.-Y.; Shang, P. PEITC triggers multiple forms of cell death by GSH-iron-ROS regulation in K7M2 murine osteosarcoma cells. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 41, 1119–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghimi, M.; Sobhan, M.R.; Jarahzadeh, M.H.; Morovati-Sharifabad, M.; Aghili, K.; Ahrar, H.; Zare-Shehneh, M.; Neamatzadeh, H. Association of GSTM1, GSTT1, GSTM3, and GSTP1 Genes Polymorphisms with Susceptibility to Osteosarcoma: A Case- Control Study and Meta-Analysis. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP 2019, 20, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Xia, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Li, A.; Li, H.; Xiao, T. LncRNA XIST from the bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell derived exosome promotes osteosarcoma growth and metastasis through miR-655/ACLY signal. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Han, T.; Su, H.; Xuan, J.; Wang, X. Comprehensive analysis of fatty acid and lactate metabolism-related genes for prognosis value, immune infiltration, and therapy in osteosarcoma patients. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 934080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; He, C.; Shu, Z.; Liu, N.; Zhong, Y.; Long, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, F.; Liu, Z.; Huang, P. Identification and experimental validation of Stearoyl-CoA desaturase is a new drug therapeutic target for osteosarcoma. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 963, 176249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Ou, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, K.; Huang, W.; Jiang, D. The mevalonate pathway promotes the metastasis of osteosarcoma by regulating YAP1 activity via RhoA. Genes Dis. 2022, 9, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Chen, W.; Long, X.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, S. iTRAQ-based proteomic analysis of the molecular mechanisms and downstream effects of fatty acid synthase in osteosarcoma cells. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2021, 35, e23653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Ji, Y.; Cui, Y.; Xu, L.; Liu, H.; Wang, J. Simvastatin-Incorporated Drug Delivery Systems for Bone Regeneration. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 2177–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Wei, R.; Zhou, J.; Wu, K.; Li, J. Emerging roles of long non-coding RNAs in osteosarcoma. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1327459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, Y. KDM4A-mediated histone demethylation of SLC7A11 inhibits cell ferroptosis in osteosarcoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 550, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, E.; Fuchs, Y. Modes of Regulated Cell Death in Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 245–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Hao, Y.; Yang, N.; Liu, M.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Liu, H.; Li, J. Oridonin-induced ferroptosis and apoptosis: A dual approach to suppress the growth of osteosarcoma cells. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimmino, A.; Gioia, M.; Clementi, M.E.; Faraoni, I.; Marini, S.; Ciaccio, C. Polydatin-Induced Shift of Redox Balance and Its Anti-Cancer Impact on Human Osteosarcoma Cells. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 47, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrens-Mas, M.; Roca, P. Phytoestrogens for Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Biology 2020, 9, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimmino, A.; Fasciglione, G.F.; Gioia, M.; Marini, S.; Ciaccio, C. Multi-Anticancer Activities of Phytoestrogens in Human Osteosarcoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, C.; Yang, T.; Deng, Z.; Song, Y.; Huang, L.; Li, F.; Li, Q.; Lin, S.; et al. EF24 induces ferroptosis in osteosarcoma cells through HMOX1. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 136, 111202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Gao, X.; Zou, L.; Lei, M.; Feng, J.; Hu, Z. Bavachin Induces Ferroptosis through the STAT3/P53/SLC7A11 Axis in Osteosarcoma Cells. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 1783485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, R.; Dong, X.; Zhuang, H.; Pang, F.; Ding, S.; Li, N.; Mai, Y.; Zhou, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J. Baicalin induces ferroptosis in osteosarcomas through a novel Nrf2/xCT/GPX4 regulatory axis. Phytomedicine 2023, 116, 154881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Wang, H.; Yang, F.; Chen, H.; He, W.; Wang, J. Curcumin Promotes Osteosarcoma Cell Death by Activating miR-125a/ERRα Signal Pathway. J. Cell. Biochem. 2017, 118, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Zeng, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Wan, Y. Fabrication of Curcumin-Modified TiO2 Nanoarrays via Cyclodextrin Based Polymer Functional Coatings for Osteosarcoma Therapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, e1901031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Fan, R.; Zhu, K.; Wang, Y.; Xie, W.; Liang, Y. Curcumin induces ferroptosis and apoptosis in osteosarcoma cells by regulating Nrf2/GPX4 signaling pathway. Exp. Biol. Med. 2023, 248, 2183–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, W.; Hu, G.; Sun, H.; Kong, Q. Bioactivities of EF24, a Novel Curcumin Analog: A Review. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wu, S.; Shi, L.; Zhang, S.; Ren, J.; Yao, S.; Yun, D.; Huang, L.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; et al. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of asymmetric EF24 analogues as potential anti-cancer agents for lung cancer. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 125, 1321–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Yang, X.; Huang, J.; Ji, C.; Li, X.; Li, L.; Zhou, J.; Hu, Y. Gambogenic acid induces cell death in human osteosarcoma through altering iron metabolism, disturbing the redox balance, and activating the P53 signaling pathway. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2023, 382, 110602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Dong, H.; Li, T.; Wang, N.; Wei, X.; Wu, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Guo, Z.; Xiao, X. The Synergistic Reducing Drug Resistance Effect of Cisplatin and Ursolic Acid on Osteosarcoma through a Multistep Mechanism Involving Ferritinophagy. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 5192271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, Y.; Wang, X.; Qian, J.; Bian, Z. Shikonin induces ferroptosis in osteosarcomas through the mitochondrial ROS-regulated HIF-1α/HO-1 axis. Phytomedicine 2024, 135, 156139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Chu, D.; Shi, J.; Xu, R.; Wang, K. Shikonin suppresses proliferation of osteosarcoma cells by inducing ferroptosis through promoting Nrf2 ubiquitination and inhibiting the xCT/GPX4 regulatory axis. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1490759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ding, S.; Fan, J.; Li, T.; Xiao, X.; Li, J. Curculigoside exhibits multiple therapeutic efficacy to induce apoptosis and ferroptosis in osteosarcoma via modulation of ROS and tumor microenvironment. Tissue Cell 2025, 93, 102745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Gong, M.; Deng, Z.; Liu, H.; Chang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Cai, L. Tirapazamine suppress osteosarcoma cells in part through SLC7A11 mediated ferroptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 567, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Ling, Y.; Jin, M.; Chen, Z.; Liu, W.; Shen, W.; Fang, T.; Li, J.; He, Y. Butyrate enhances erastin-induced ferroptosis of osteosarcoma cells via regulating ATF3/SLC7A11 pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 957, 176009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiacong, H.; Qirui, Y.; Haonan, L.; Yichang, S.; Yan, C.; Keng, C. Zoledronic acid induces ferroptosis by upregulating POR in osteosarcoma. Med. Oncol. 2023, 40, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.; Huang, J.; Sun, W.; Wang, G.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Lv, Y.; Wu, G.; Cao, J.; Liu, M.; et al. Zoledronic acid induces ferroptosis by reducing ubiquinone and promoting HMOX1 expression in osteosarcoma cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1071946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palliyaguru, D.L.; Yuan, J.-M.; Kensler, T.W.; Fahey, J.W. Isothiocyanates: Translating the Power of Plants to People. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, e1700965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasukabe, T.; Honma, Y.; Okabe-Kado, J.; Higuchi, Y.; Kato, N.; Kumakura, S. Combined treatment with cotylenin A and phenethyl isothiocyanate induces strong antitumor activity mainly through the induction of ferroptotic cell death in human pancreatic cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 36, 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Zhen, C.; Liu, J.; Shang, P. β-Phenethyl Isothiocyanate Induces Cell Death in Human Osteosarcoma through Altering Iron Metabolism, Disturbing the Redox Balance, and Activating the MAPK Signaling Pathway. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 5021983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaw-Luximon, A.; Jhurry, D. Artemisinin and its derivatives in cancer therapy: Status of progress, mechanism of action, and future perspectives. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2017, 79, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salaroli, R.; Andreani, G.; Bernardini, C.; Zannoni, A.; La Mantia, D.; Protti, M.; Forni, M.; Mercolini, L.; Isani, G. Anticancer activity of an Artemisia annua L. hydroalcoholic extract on canine osteosarcoma cell lines. Res. Vet. Sci. 2022, 152, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ding, X.; Wu, H.; Liu, C. Artemisinin inhibits angiogenesis by regulating p38 MAPK/CREB/TSP-1 signaling pathway in osteosarcoma. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 11462–11470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.; Ao, P.Y.; Zhao, Y.Q.; Huang, S.Z.; Jin, Y.; Liu, J.J.; Luo, J.P.; Zheng, J.; Shi, D.P. Effect and mechanism of dihydroartemisinin on proliferation, metastasis and apoptosis of human osteosarcoma cells. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2015, 29, 881–887. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Ding, C.; Zhu, W.; Li, X.; Chen, T.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, T.-C.; Ma, W. Chemotherapeutic drugs induce oxidative stress associated with DNA repair and metabolism modulation. Life Sci. 2022, 289, 120242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, E.; Attri, D.C.; Sati, P.; Dhyani, P.; Szopa, A.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Hano, C.; Calina, D.; Cho, W.C. Recent updates on anticancer mechanisms of polyphenols. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 1005910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhosale, P.B.; Ha, S.E.; Vetrivel, P.; Kim, H.H.; Kim, S.M.; Kim, G.S. Functions of polyphenols and its anticancer properties in biomedical research: A narrative review. Transl. Cancer Res. 2020, 9, 7619–7631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedzwiecki, A.; Roomi, M.; Kalinovsky, T.; Rath, M. Anticancer Efficacy of Polyphenols and Their Combinations. Nutrients 2016, 8, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Li, T.; Ye, J.; Sun, F.; Hou, B.; Saeed, M.; Gao, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Xu, Z.; et al. Acidity-Activatable Dynamic Nanoparticles Boosting Ferroptotic Cell Death for Immunotherapy of Cancer. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2101155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yao, L.; Hu, Q.; Liu, H.; Zhao, G.; Wang, K.; Zeng, J.; Sun, M.; Lv, C. Capsaicin Enhanced the Efficacy of Photodynamic Therapy Against Osteosarcoma via a Pro-Death Strategy by Inducing Ferroptosis and Alleviating Hypoxia. Small 2024, 20, 2306916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Li, Y.; Wu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Li, X.; Luo, W. Eriodictyol-cisplatin coated nanomedicine synergistically promote osteosarcoma cells ferroptosis and chemosensitivity. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wu, J.; He, M.; Hou, X.; Wang, Y.; Cai, X.; Xin, H.; Gao, F.; Chen, Y. Combined Cancer Chemo-Photodynamic and Photothermal Therapy Based on ICG/PDA/TPZ-Loaded Nanoparticles. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 2172–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.B.; Williamson, S.K. Tirapazamine: A novel agent targeting hypoxic tumor cells. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2009, 18, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Jiang, W.; Wang, Q.; Hang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. ROS-sensitive biomimetic nanocarriers modulate tumor hypoxia for synergistic photodynamic chemotherapy. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 3706–3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Zhao, D.; Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Cao, L.; Sun, J.; Jiang, Q.; He, Z. Recent progress of hypoxia-modulated multifunctional nanomedicines to enhance photodynamic therapy: Opportunities, challenges, and future development. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2020, 10, 1382–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Ran, X.; Li, B.; Li, Y.; He, D.; Huang, B.; Fu, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, W. Sodium Butyrate Inhibits Inflammation and Maintains Epithelium Barrier Integrity in a TNBS-induced Inflammatory Bowel Disease Mice Model. eBioMedicine 2018, 30, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medzhitov, R.; Horng, T. Transcriptional control of the inflammatory response. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatoum, H.T.; Lin, S.-J.; Smith, M.R.; Barghout, V.; Lipton, A. Zoledronic acid and skeletal complications in patients with solid tumors and bone metastases: Analysis of a national medical claims database. Cancer 2008, 113, 1438–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohno, N.; Aogi, K.; Minami, H.; Nakamura, S.; Asaga, T.; Iino, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Goessl, C.; Ohashi, Y.; Takashima, S. Zoledronic acid significantly reduces skeletal complications compared with placebo in Japanese women with bone metastases from breast cancer: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 3314–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christou, A.; Ferreira, N.; Sophocleous, A. Effects of zoledronic acid on osteosarcoma progression and metastasis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Exp. Med. 2023, 23, 3041–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.H.; Kim, M.-S.; Takahashi, A.; Suzuki, M.; Vares, G.; Uzawa, A.; Fujimori, A.; Ohno, T.; Sai, S. Carbon-Ion Beam Irradiation Alone or in Combination with Zoledronic acid Effectively Kills Osteosarcoma Cells. Cancers 2020, 12, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piperno-Neumann, S.; Le Deley, M.-C.; Rédini, F.; Pacquement, H.; Marec-Bérard, P.; Petit, P.; Brisse, H.; Lervat, C.; Gentet, J.-C.; Entz-Werlé, N.; et al. Zoledronate in combination with chemotherapy and surgery to treat osteosarcoma (OS2006): A randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 1070–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Ye, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, B.; Li, K.; Zhou, K.; Cao, H.; Zheng, J.; Wang, G. Employing machine learning using ferroptosis-related genes to construct a prognosis model for patients with osteosarcoma. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1099272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, N.; Fatima, S.; Tahar, M.; Rizwanullah; Firdous, J.; Ahmad, R.; Mazhar, F.; Khan, M.A. Nanomedicines in Diagnosis and Treatment of Cancer: An Update. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020, 26, 1216–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira-Silva, M.; Alvarez-Lorenzo, C.; Concheiro, A.; Santos, A.C.; Veiga, F.; Figueiras, A. Nanomedicine in osteosarcoma therapy: Micelleplexes for delivery of nucleic acids and drugs toward osteosarcoma-targeted therapies. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2020, 148, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, T.; Ma, Q.; Zhang, C.; He, X.; Wang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Qin, K.; Liao, F.; Zhou, P.; Xu, P.; et al. A novel nanomedicine for osteosarcoma treatment: Triggering ferroptosis through GSH depletion and inhibition for enhanced synergistic PDT/PTT therapy. J. Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zuo, Z.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, W. Tumor Cell Membrane-Encapsulated Nanoparticles Composed of FeS2 and Radical-Initiator Nanoparticles for Osteosarcoma Cell Death. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 10138–10149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Jin, L.; Liu, B.; Xia, K.; Wang, J.; Gao, J.; Liang, C.; Tao, H. Autophagy inhibitor enhance ZnPc/BSA nanoparticle induced photodynamic therapy by suppressing PD-L1 expression in osteosarcoma immunotherapy. Biomaterials 2019, 192, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Feng, L.; Yang, P.; Liu, B.; Gai, S.; Yang, G.; Dai, Y.; Lin, J. Enhanced up/down-conversion luminescence and heat: Simultaneously achieving in one single core-shell structure for multimodal imaging guided therapy. Biomaterials 2016, 105, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buglione, A.; Becerril Rodriguez, D.; Dogali, S.; Alloisio, G.; Ciaccio, C.; Luce, M.; Marini, S.; Campagnolo, L.; Cricenti, A.; Gioia, M. A ‘Spicy’ Mechanotransduction Switch: Capsaicin-Activated TRPV1 Receptor Modulates Osteosarcoma Cell Behavior and Drug Sensitivity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Dai, W.; Man, J.; Hu, H.; Jin, Q.; Zhang, B.; Tang, Z. Lonidamine liposomes to enhance photodynamic and photothermal therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma by inhibiting glycolysis. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Wang, M.; Huang, J.; Tang, S.; Yang, J.; Xu, Z.; Xu, G.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, C. High-performance pyrite nano-catalyst driven photothermal/chemodynamic synergistic therapy for Osteosarcoma. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Deng, X.; Xing, X.; Hu, H.; Zhang, Y. Iron-Based Nanovehicle Delivering Fin56 for Hyperthermia-Boosted Ferroptosis Therapy Against Osteosarcoma. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, K.; Skouta, R.; Kaplan, A.; Yang, W.S.; Hayano, M.; Dixon, S.J.; Brown, L.M.; A Valenzuela, C.; Wolpaw, A.J.; Stockwell, B.R. Global survey of cell death mechanisms reveals metabolic regulation of ferroptosis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016, 12, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debnath, S.; Sarkar, A.; Das Mukherjee, D.; Ray, S.; Mahata, B.; Mahata, T.; Parida, P.K.; Das, T.; Mukhopadhyay, R.; Ghosh, Z.; et al. Eriodictyol mediated selective targeting of the TNFR1/FADD/TRADD axis in cancer cells induce apoptosis and inhibit tumor progression and metastasis. Transl. Oncol. 2022, 21, 101433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Gu, M.; Wu, M.; Ji, L. Eriodictyol suppresses the malignant progression of colorectal cancer by downregulating tissue specific transplantation antigen P35B (TSTA3) expression to restrain fucosylation. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 5551–5563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Du, S.; Wang, S.; Ye, K. Ferroptosis in osteosarcoma: A promising future. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1031779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Lei, J.; Xu, D.; Yu, W.; Bai, J.; Wu, G. Integrative analyses of ferroptosis and immune related biomarkers and the osteosarcoma associated mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, J.; Liu, S. Clinical significance and immune landscape of a novel ferroptosis-related prognosis signature in osteosarcoma. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastiano, M.R.; Konstantinidou, G. Targeting Long Chain Acyl-CoA Synthetases for Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, H.; Guan, J.; Mo, L.; He, J.; Wu, Z.; Lin, X.; Liu, B.; Yuan, Z. ATF4 regulated by MYC has an important function in anoikis resistance in human osteosarcoma cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 17, 3658–3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Saide, A.; Cagliani, R.; Cantile, M.; Botti, G.; Russo, G. rpL3 promotes the apoptosis of p53 mutated lung cancer cells by down-regulating CBS and NFκB upon 5-FU treatment. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishizawa, N.; Harada, H.; Kumamoto, Y.; Kaizu, T.; Katoh, H.; Tajima, H.; Ushiku, H.; Yokoi, K.; Igarashi, K.; Fujiyama, Y.; et al. Diagnostic potential of hypermethylation of the cysteine dioxygenase 1 gene (CDO 1) promoter DNA in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Sci. 2019, 110, 2846–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, C.; Cui, X.; Zhan, B.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Bi, J.; Zhang, Z.; Kong, C. Inhibition of stearoyl CoA desaturase-1 activity suppresses tumour progression and improves prognosis in human bladder cancer. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 2064–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfarsi, L.H.; El-Ansari, R.; Craze, M.L.; Masisi, B.K.; Mohammed, O.J.; Ellis, I.O.; Rakha, E.A.; Green, A.R. Co-Expression Effect of SLC7A5/SLC3A2 to Predict Response to Endocrine Therapy in Oestrogen-Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Du, H.; Lu, J.; Wang, H. Construction and validation of a predictive nomogram for ferroptosis-related genes in osteosarcoma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 14227–14239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, M.; Lang, J. The roles of metallothioneins in carcinogenesis. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 11, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Qin, S. Glucose-6-phosphate Dehydrogenase: A Biomarker and Potential Therapeutic Target for Cancer. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2014, 14, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocellin, S.; Tropea, S.; Benna, C.; Rossi, C.R. Circadian pathway genetic variation and cancer risk: Evidence from genome-wide association studies. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, F.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zou, Y.; Han, H.; Huang, J. Baicalein induces human osteosarcoma cell line MG-63 apoptosis via ROS-induced BNIP3 expression. Tumor Biol. 2015, 36, 4731–4740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Hou, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhu, P.; Wan, X.; Zhao, M.; Peng, M.; Zeng, H.; Li, Q.; Jin, T.; et al. A Novel Long Non-Coding RNA lnc030 Maintains Breast Cancer Stem Cell Stemness by Stabilizing SQLE mRNA and Increasing Cholesterol Synthesis. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2002232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Guo, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhu, Y. Exploration of various roles of hypoxia genes in osteosarcoma. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, F.J.; Chinnaiyan, A.M. The Role of Non-coding RNAs in Oncology. Cell 2019, 179, 1033–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.B.; Wan, Y.J.; Chen, D.H.; Xiao, Y.J.; Shen, L.S.; Peng, Z. Identification of an Iron Metabolism-Related lncRNA Signature for Predicting Osteosarcoma Survival and Immune Landscape. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 816460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ding, W.; Wang, J.; Ao, X.; Xue, J. Non-coding RNAs in lung cancer: Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1256537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Wang, Y.; Ma, C.; Lv, Q. Competitive endogenous network of circRNA, lncRNA, and miRNA in osteosarcoma chemoresistance. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2023, 28, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, Y.; Gao, L.; Wang, B.; Ren, W.; Liang, K.X.; Zhi, K. Ferroptosis Holds Novel Promise in Treatment of Cancer Mediated by Non-coding RNAs. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 686906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; He, Y.; Yuan, C. LncSNHG14 promotes nutlin3a resistance by inhibiting ferroptosis via the miR-206/SLC7A11 axis in osteosarcoma cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 2023, 30, 704–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, Z.; Du, S.; Li, W.; Bai, Y.; Lu, C.; Xu, T. A novel ferroptosis-related microRNA signature with prognostic value in osteosarcoma. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2023, 55, 1758–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Luo, Y.; Wang, C.; Han, D.; Sun, W. Circular RNA circBLNK promotes osteosarcoma progression and inhibits ferroptosis in osteosarcoma cells by sponging miR-188-3p and regulating GPX4 expression. Oncol. Rep. 2023, 50, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Andresen, J.L.; Manan, R.S.; Langer, R. Nucleic acid delivery for therapeutic applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 178, 113834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, W.; Rong, X.; Zhong, Z.; Jiang, L.; Chen, S.; Li, C.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, J. Delivery of miRNAs Using Nanoparticles for the Treatment of Osteosarcoma. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 8641–8660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Jike, Y.; Liu, K.; Gan, F.; Zhang, K.; Xie, M.; Zhang, J.; Chen, C.; Zou, X.; Jiang, X.; et al. Exosome-mediated miR-144-3p promotes ferroptosis to inhibit osteosarcoma proliferation, migration, and invasion through regulating ZEB1. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, S.; Liang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhong, W.; Ma, Y. MAT2A inhibits the ferroptosis in osteosarcoma progression regulated by miR-26b-5p. J. Bone Oncol. 2023, 41, 100490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Wang, Y.; Xie, J.; Pu, J.; Shen, Z.; Wang, A.; Li, T.; Wang, T.; Li, G.; Liu, Y.; et al. M7G modification of FTH1 and pri-miR-26a regulates ferroptosis and chemotherapy resistance in osteosarcoma. Oncogene 2024, 43, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Chen, L.; Wang, C.; Zhang, L.; Xu, W. MicroRNA-1287-5p promotes ferroptosis of osteosarcoma cells through inhibiting GPX4. Free Radic. Res. 2021, 55, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Feng, J.; Huang, S.; Li, Q. LncRNA-PVT1 Inhibits Ferroptosis through Activating STAT3/GPX4 Axis to Promote Osteosarcoma Progression. Front. Biosci. Landmark 2024, 29, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.-Y.; Jian, Y.-K.; Zhu, H.-Y.; Li, B. lncRNAPVT1 targets miR-152 to enhance chemoresistance of osteosarcoma to gemcitabine through activating c-MET/PI3K/AKT pathway. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2019, 215, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Yang, G.; Xu, J.; Zhang, C. Silencing of SNHG6 induced cell autophagy by targeting miR-26a-5p/ULK1 signaling pathway in human osteosarcoma. Cancer Cell Int. 2019, 19, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, R.; Lei, X.; Mao, L.; Yin, Z.; Zhong, X.; Cao, W.; Zheng, Q.; Li, D. Comprehensive Analysis of a Ferroptosis-Related lncRNA Signature for Predicting Prognosis and Immune Landscape in Osteosarcoma. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 880459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, H.; Shang, G.; Cui, Y.; Liu, J.; Sun, X.; Cao, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y. Long noncoding RNA APTR contributes to osteosarcoma progression through repression of miR-132-3p and upregulation of yes-associated protein 1. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 8998–9007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Liu, F.; Wang, Z.; Gong, H.; Zhang, M.; Jia, Z.; Zhai, X. CircKIF4A enhances osteosarcoma proliferation and metastasis by sponging MiR-515-5p and upregulating SLC7A11. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 4525–4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Zhu, X.; Ke, Y.; Xiao, D.; Liang, C.; Chen, J.; Chang, Y. LncRNA FTX inhibition restrains osteosarcoma proliferation and migration via modulating miR-320a/TXNRD1. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2020, 21, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, X.; Zhu, C.; Wang, K. lncRNA PVT1: A novel oncogene in multiple cancers. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2022, 27, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, K.; Foulkes, P.; Hills, F.; Roberts, H.C.; Stordal, B. The efficacy of gemcitabine and docetaxel chemotherapy for the treatment of relapsed and refractory osteosarcoma: A systematic review and pre-clinical study. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e70248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Kawashima, H.; Sasaki, T.; Ariizumi, T.; Oike, N.; Ogose, A. Heterogeneous c-Met Activation in Osteosarcoma Dictates Synergistic Vulnerability to Combined c-Met Inhibition and Methotrexate Therapy. Anti-Cancer Res. 2025, 45, 2791–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhuang, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, Y. Inhibition of c-Met activation sensitizes osteosarcoma cells to cisplatin via suppression of the PI3K–Akt signaling. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 526, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Wu, X.; Liu, F.; Li, M.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhu, K.; Jia, X.; Wang, B.; et al. Long non-coding RNA PVT1 promotes glycolysis and tumor progression by regulating miR-497/HK2 axis in osteosarcoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 490, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Fang, L.; Zhao, H.; Xiang, T.; Wang, D. MDM2 inhibitor Nutlin-3a suppresses proliferation and promotes apoptosis in osteosarcoma cells. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2012, 44, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, L.S.; Andersen, M.S.; Stagsted, L.V.W.; Ebbesen, K.K.; Hansen, T.B.; Kjems, J. The biogenesis, biology and characterization of circular RNAs. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 675–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Jing, J.; Li, J. The Roles of Circular RNAs in Osteosarcoma. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 6378–6382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Q. CircRNA_103801 accelerates proliferation of osteosarcoma cells by sponging miR-338-3p and regulating HIF-1/Rap1/PI3K-Akt pathway. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. AGENTS 2021, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, G.; Han, Z.; Wang, W.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, J. Silencing hsa_circRNA_0008035 exerted repressive function on osteosarcoma cell growth and migration by upregulating microRNA-375. Cell Cycle 2020, 19, 2139–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Jiang, C.; Zou, Z.; Huang, H.; Li, X.; Xu, S.; Tan, R. Ferritinophagy in the etiopathogenic mechanism of related diseases. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2023, 117, 109339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancias, J.D.; Wang, X.; Gygi, S.P.; Harper, J.W.; Kimmelman, A.C. Quantitative proteomics identifies NCOA4 as the cargo receptor mediating ferritinophagy. Nature 2014, 509, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochette, L.; Dogon, G.; Rigal, E.; Zeller, M.; Cottin, Y.; Vergely, C. Lipid Peroxidation and Iron Metabolism: Two Corner Stones in the Homeostasis Control of Ferroptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Y.; Liu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Wu, J. The emerging role of nuclear receptor coactivator 4 in health and disease: A novel bridge between iron metabolism and immunity. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Codina, N.; del Rey, M.Q.; Kapner, K.S.; Zhang, H.; Gikandi, A.; Malcolm, C.; Poupault, C.; Kuljanin, M.; John, K.M.; Biancur, D.E.; et al. NCOA4-Mediated Ferritinophagy Is a Pancreatic Cancer Dependency via Maintenance of Iron Bioavailability for Iron-Sulfur Cluster Proteins. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 2180–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Li, C.; Liao, S.; Yao, X.; Ouyang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Yao, F. Ferritinophagy, a form of autophagic ferroptosis: New insights into cancer treatment. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1043344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, N.; Peng, M.; Oyang, L.; Jiang, X.; Peng, Q.; Zhou, Y.; He, Z.; Liao, Q. Ferritinophagy: Research advance and clinical significance in cancers. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Hyun, D.-H. The Interplay between Intracellular Iron Homeostasis and Neuroinflammation in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotla, N.K.; Dutta, P.; Parimi, S.; Das, N.K. The Role of Ferritin in Health and Disease: Recent Advances and Understandings. Metabolites 2022, 12, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana-Codina, N.; Gikandi, A.; Mancias, J.D. The Role of NCOA4-Mediated Ferritinophagy in Ferroptosis. In Ferroptosis: Mechanism and Diseases; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Florez, A.F., Alborzinia, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 1301, pp. 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Mou, H.; Huang, Q.; Jian, C.; Tao, Y.; Tan, F.; Ou, Y. Synergistic induction of ferroptosis by targeting HERC1-NCOA4 axis to enhance the photodynamic sensitivity of osteosarcoma. Redox Biol. 2024, 76, 103328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lozovatsky, L.; Sukumaran, A.; Gonzalez, L.; Jain, A.; Liu, D.; Ayala-Lopez, N.; Finberg, K.E. NCOA4 is Regulated by HIF and Mediates Mobilization of Murine Hepatic Iron Stores After Blood Loss. Blood 2020, 136, 2691–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuno, S.; Fujita, H.; Tanaka, Y.; Ogra, Y.; Iwai, K. Iron-induced NCOA4 condensation regulates ferritin fate and iron homeostasis. EMBO Rep. 2022, 23, e54278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galy, B.; Conrad, M.; Muckenthaler, M. Mechanisms controlling cellular and systemic iron homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Chen, X.; Tan, Q.; Zhou, H.; Xu, J.; Gu, Q. Inhibiting Ferroptosis through Disrupting the NCOA4–FTH1 Interaction: A New Mechanism of Action. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021, 7, 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, J.; Debnath, J. Autophagy at the crossroads of catabolism and anabolism. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 16, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, J.; Omiya, S.; Rusu, M.-C.; Ueda, H.; Murakawa, T.; Tanada, Y.; Abe, H.; Nakahara, K.; Asahi, M.; Taneike, M.; et al. Iron derived from autophagy-mediated ferritin degradation induces cardiomyocyte death and heart failure in mice. eLife 2021, 10, e62174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, W.; Xie, Y.; Song, X.; Sun, X.; Lotze, M.T.; Zeh, H.J., 3rd; Kang, R.; Tang, D. Autophagy promotes ferroptosis by degradation of ferritin. Autophagy 2016, 12, 1425–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Liu, Q.; Shan, X.; Gao, W.; Chen, Q. ATM orchestrates ferritinophagy and ferroptosis by phosphorylating NCOA4. Autophagy 2023, 19, 2062–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, Q.; Li, R.; Zhang, J.; Ye, X.; Li, X. YAP1 protects against septic liver injury via ferroptosis resistance. Cell Biosci. 2022, 12, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Peng, L.; Huo, S.; Peng, D.; Gou, J.; Shi, W.; Tao, J.; Jiang, T.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Q.; et al. STAT3 signaling promotes cardiac injury by upregulating NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy and ferroptosis in high-fat-diet fed mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 201, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchinetti, M.M. Heme-Oxygenase-1. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2020, 32, 1239–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancias, J.D.; Vaites, L.P.; Nissim, S.; E Biancur, D.; Kim, A.J.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Goessling, W.; Kimmelman, A.C.; Harper, J.W. Ferritinophagy via NCOA4 is required for erythropoiesis and is regulated by iron dependent HERC2-mediated proteolysis. eLife 2015, 4, e10308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yuan, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Xie, Q.; Ma, R.; Wang, J.; Ren, M.; Lu, D.; Xu, Z. d-Borneol enhances cisplatin sensitivity via autophagy dependent EMT signaling and NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy. Phytomedicine 2022, 106, 154411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nai, A.; Lidonnici, M.R.; Federico, G.; Pettinato, M.; Olivari, V.; Carrillo, F.; Crich, S.G.; Ferrari, G.; Camaschella, C.; Silvestri, L.; et al. NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy in macrophages is crucial to sustain erythropoiesis in mice. Haematologica 2021, 106, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; You, J.H.; Roh, J.-L. Poly(rC)-binding protein 1 represses ferritinophagy-mediated ferroptosis in head and neck cancer. Redox Biol. 2022, 51, 102276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, H.; Zhou, L.; Zhu, G.; Zheng, Y.; Ye, Z.; Huang, Z.; Teng, X.; Ai, C.; Ge, G.; Xiao, Y. Super-Resolution Imaging of Autophagy by a Preferred Pair of Self-Labeling Protein Tags and Fluorescent Ligands. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 15057–15066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masaldan, S.; Clatworthy, S.A.; Gamell, C.; Meggyesy, P.M.; Rigopoulos, A.-T.; Haupt, S.; Haupt, Y.; Denoyer, D.; Adlard, P.A.; Bush, A.I.; et al. Iron accumulation in senescent cells is coupled with impaired ferritinophagy and inhibition of ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2018, 14, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, O.; Canadas, A.; Faria, F.; Oliveira, E.; Amorim, I.; Seixas, F.; Gama, A.; Lobo-Da-Cunha, A.; da Silva, B.M.; Porto, G.; et al. Expression of iron-related proteins in feline and canine mammary gland reveals unexpected accumulation of iron. Biotech. Histochem. 2017, 92, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, S.; Dunning, M.D.; De Brot, S.; Grau-Roma, L.; Mongan, N.P.; Rutland, C.S. Comparative review of human and canine osteosarcoma: Morphology, epidemiology, prognosis, treatment and genetics. Acta Vet. Scand. 2017, 59, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y.; Du, X.; Liu, S.; Ji, J.; Yang, X.; Zhai, G. Oxygen-boosted biomimetic nanoplatform for synergetic phototherapy/ferroptosis activation and reversal of immune-suppressed tumor microenvironment. Biomaterials 2022, 290, 121832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, T.; Qian, H.; Lei, P.; Hu, Y. Ferroptosis-related gene signature associates with immunity and predicts prognosis accurately in patients with osteosarcoma. Cancer Sci. 2021, 112, 4785–4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wang, H.; Qi, G.; Jiang, C.; Chen, K.; Yan, Z. Iron overload-induced ferroptosis of osteoblasts inhibits osteogenesis and promotes osteoporosis: An in vitro and in vivo study. IUBMB Life 2022, 74, 1052–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ru, Q.; Li, Y.; Xie, W.; Ding, Y.; Chen, L.; Xu, G.; Wu, Y.; Wang, F. Fighting age-related orthopedic diseases: Focusing on ferroptosis. Bone Res. 2023, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Naowarojna, N.; Zou, Y. Stratifying ferroptosis sensitivity in cells and mouse tissues by photochemical activation of lipid peroxidation and fluorescent imaging. STAR Protoc. 2022, 3, 101189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayaman, R.W.; Saad, M.; Thorsson, V.; Hu, D.; Hendrickx, W.; Roelands, J.; Porta-Pardo, E.; Mokrab, Y.; Farshidfar, F.; Kirchhoff, T.; et al. Germline genetic contribution to the immune landscape of cancer. Immunity 2021, 54, 367–386.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nirala, B.K.; Yamamichi, T.; Petrescu, D.I.; Shafin, T.N.; Yustein, J.T. Decoding the Impact of Tumor Microenvironment in Osteosarcoma Progression and Metastasis. Cancers 2023, 15, 5108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, T.; Han, J.; Yang, L.; Cai, Z.; Sun, W.; Hua, Y.; Xu, J. Immune Microenvironment in Osteosarcoma: Components, Therapeutic Strategies and Clinical Applications. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 907550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.; Luo, J.; Wu, Y.; Shen, G.; Kuang, X. The biological essence of synthetic lethality: Bringing new opportunities for cancer therapy. MedComm-Oncol. 2024, 3, e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinowaki, Y.; Taguchi, T.; Onishi, I.; Kirimura, S.; Kitagawa, M.; Yamamoto, K. Overview of Ferroptosis and Synthetic Lethality Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Nanoplatform | Cell Line/In Vivo Model | Combined Treatment | Molecular Mechanism | Observed Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI@HSA NPs (capsaicin + IR780 in albumin NPs) | 143B, HOS xenograft | capsaicin + PDT | ↑ TRPV1/Ca2+, ↓ Nrf2/GPX4, HIF-1α; ↑ MAPK, ↓ PI3K/AKT | ↑ ferroptosis, ↓ tumor hypoxia, ↓ tumor growth, good biosafety | [183] |

| CSIR (SRF@CuSO4·5H2O@IR780) | K7M2 xenograft | PDT + PTT | ↓ xCT | ↓ GSH, ↑ ROS, ↑ ferroptosis, ↓ tumor growth | [199] |

| FeS2@CP NPs | U2OS, MNNG/HOS xenograft | PTT + CDT | ↓ GPX4 | ↑ Fe2+, ROS, LPO, ↓ GSH, ↑ ferroptosis, apoptosis, ↓ tumor growth, minimal side effects | [205] |

| FAM (FeS2-AIPH@Membrane) | MNNG/HOS xenograft | PTT + CDT + TDT | __ | ROS-induced tumor ablation, low systemic toxicity | [200] |

| SR-Fin56 (Fe3O4@SiO2-RGD loaded with Fin56) | MNNG/HOS xenograft | PTT + CDT | ↓ GPX4 | ↓ GSH, ↑ Fe2+, ROS, LPO, ↑ ferroptosis, safe and effective in vivo | [206] |

| HMPB@Cisplatin@Eriodictyol | U2OS, MG63, 293T, xenograft | cisplatin + eriodictyol | ↓ GPX4 | ↓ GSH, ↑ Fe2+, ROS, LPO, ↑ ferroptosis, ↑ cisplatin sensitivity; no organ toxicity | [184] |

| FR-miRNAs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Trend in OS | Functional Effects | Model Type | References | |

| miR-593 | upregulated | regulates FRGs; promotes proliferation and migration; associated with poor prognosis. | HOS, in silico | [232] |

| miR-635 | downregulated | regulates FRGs; suppresses proliferation and migration; high expression correlates with favorable prognosis. | HOS, in silico | [232] |

| miR-206 | upregulated | promotes ferroptosis via ↑ PTGS2, KEAP1 and ↓ GPX4, SLC7A11, Nrf2, HO-1; increases ROS, Fe2, LPO; negatively regulated by lncRNA SNHG14 | SJSA1 | [231] |

| miR-188-3p | downregulated | promotes ferroptosis via ↓ GPX4T; tumor-suppressive; negatively regulated by circBLNK | HOS, SJSA-1, MG63, U2OS, tissues | [233] |

| miR-144-3p | downregulated | promotes ferroptosis via ↓ ZEB, ↑ ACSL4, ↓ GPX4, SLC7A11; affects iron homeostasis and metabolism, inhibits proliferation, migration, and invasion of OS cells. | 143B, SW1353, MG-63, SaOS-2, U2OS, nude mice | [236] |

| miR-26b-5p | upregulated | ↓ MAT2A → promotes ferroptosis via ↓ STAT3/SLC7A11 | MNNG/HOS, U2OS, nude mice | [237] |

| miR-26a-5p | upregulated | promotes ferroptosis via ↓ FTH1; increases sensitivity to cisplatin/doxorubicin; regulated by METTL1, which enhances miR-26a/FTH1 interaction | U2OS, 143B xenograft | [238] |

| miR-1287-5p | downregulated | promotes ferroptosis via ↓ GPX4; ↑ cisplatin sensitivity | SaOS2, U2OS | [239] |

| FR-lncRNAs | ||||

| PVT1 | upregulated | inhibits ferroptosis via ↑ STAT3/GPX4; ↑ metastasis | MG63 | [240] |

| upregulated | regulates glycolysis and chemoresistance through ↑ c-MET/PI3K/AKT | MG63 | [241] | |

| SNHG14 | upregulated | sponges miR-206 → inhibits ferroptosis via ↑ SLC7A11; increases nutlin-3a resistance | nutlin3a-resistant NR-SJSA1 | [231] |

| SNHG6 | upregulated | promotes autophagy via miR-26a-5p/ULK1 axis | MG63 | [242] |

| upregulated | possibly regulates ferroptosis indirectly, correlates to OS prognosis and immunity | in silico | [243] | |

| APTR | upregulated | suppresses miR-132-3p → ↑ YAP1 → promotes proliferation and invasion | MG63, 143B, Saos-2, HOS | [244] |

| upregulated | included in high-risk ferroptosis-related signatures | in silico | [243] | |

| GAS5 | — | included in iron metabolism-related prognostic models; correlates with OS progression and immunotherapy response. | in silico | [227] |

| UNC5B-AS1 | ||||

| LINC01060 | ||||

| AC124798.1 | ||||

| AC104825.1 | ||||

| LINC02298 | downregulated | negatively correlated with PD-L1 → reduce immune suppression | in silico | [243] |

| LINC01549 | ||||

| AC010609.1 | ||||

| LINC02593 | ||||

| AC093673.1 | upregulated | positively correlated with PD-L1 → promote immune evasion | in silico | [243] |

| GAPLINC | ||||

| AL133371.2 | ||||

| CARD8-AS1 | ||||

| DSCR8 | downregulated | correlates with favorable prognosis; involved in immune cell infiltration | in silico | [102] |

| LOH12CR2 | ||||

| AC027307.2 | ||||

| AC025048.2 | ||||

| FR-circRNAs | ||||

| circBLNK | upregulated | sponges miR-188-3p → inhibits ferroptosis via ↑ GPX4; promotes OS progression | HOS, SJSA-1, MG63 and U2OS, tissues | [233] |

| circKIF4A | upregulated | sponges miR-515-5p → inhibits ferroptosis via ↑ SLC7A11, ↑ metastasis and proliferation | SOSP-9607, HOS, U2OS, SW1353, Saos-2, tissues | [245] |