Development of a Collagen–Cerium Oxide Nanohydrogel for Wound Healing: In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To develop the synthesis of new collagen-nanoceria composites with new pharmacological and regenerative properties.

- To conduct cultural studies and select the best components for the effectiveness and safety of the nanocomposites.

- To obtain data on the induction and protective activity for parameters such as general toxicity, antioxidant, prooxidant, antigenotoxic, and promutagenic activity, using live bacterial biosensors.

- To study the effectiveness and regenerative potential of the developed nanocompositions on full-thickness skin wound models in animals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Synthesis of the Nanocomposites

2.2.1. Collagen-Containing Solution

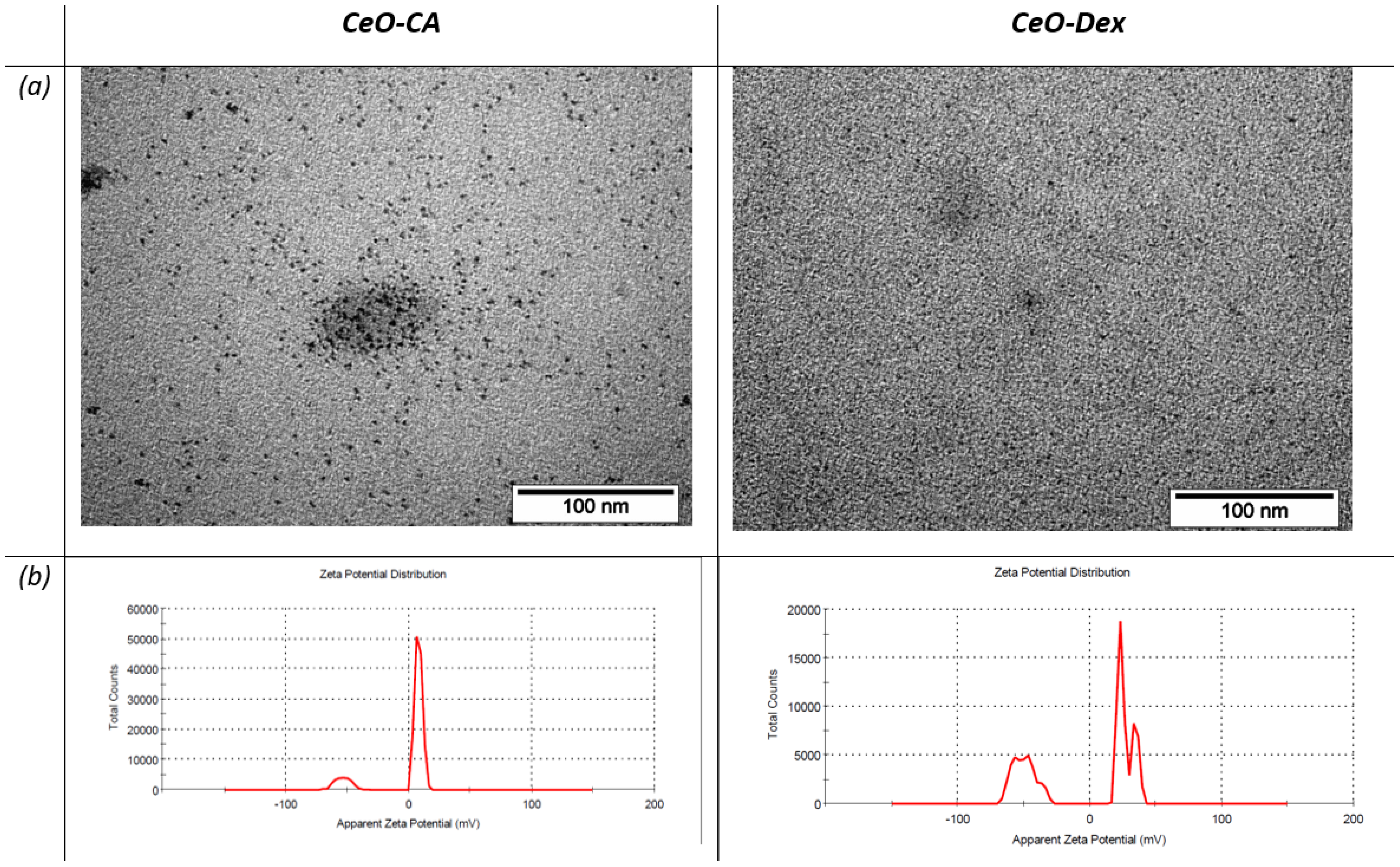

2.2.2. Nanocerium

2.2.3. Collagen–Nanocerium Composites

2.3. Influence of Various Concentrations of Collagen–Nanocerium Composites and Their Components on Human Fibroblast Cytotoxicity and Proliferative and Metabolic Activity

2.3.1. MTT Assay

2.3.2. Quantitative Cell Counting and Cytotoxicity Assessment

2.4. Bacterial Biosensors

Bioluminescent Test with Inducible E. coli Strains

2.5. In Vivo Studies of Collagen–Nanocerium Hydrogel Drug Prototypes to Determine Efficacy in an Animal Model of Acute Full-Thickness Skin Wound

2.5.1. Treatment and Groups

2.5.2. Assessment of Effectiveness

2.5.3. Histological and Morphometric Examination of the Wound Tissues

2.5.4. Ethics

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.6.1. Cultural Studies on Fibroblasts

2.6.2. Lux-Biosensor Study

2.6.3. Statistical Analysis of Animal Study Results

3. Results

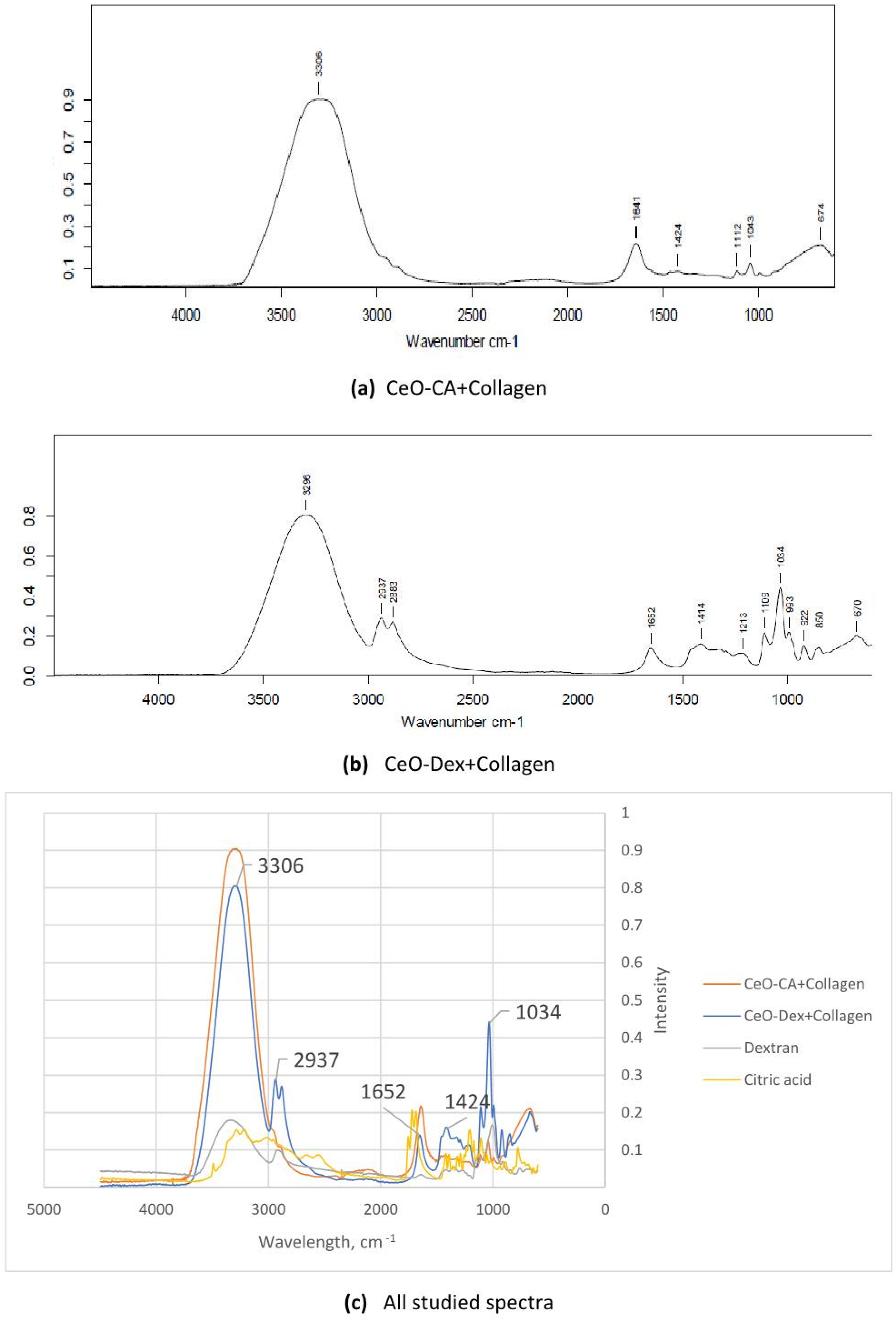

3.1. FTIR Spectroscopy Results of Nanocomposites

3.2. Results of the Cell Culture Studies

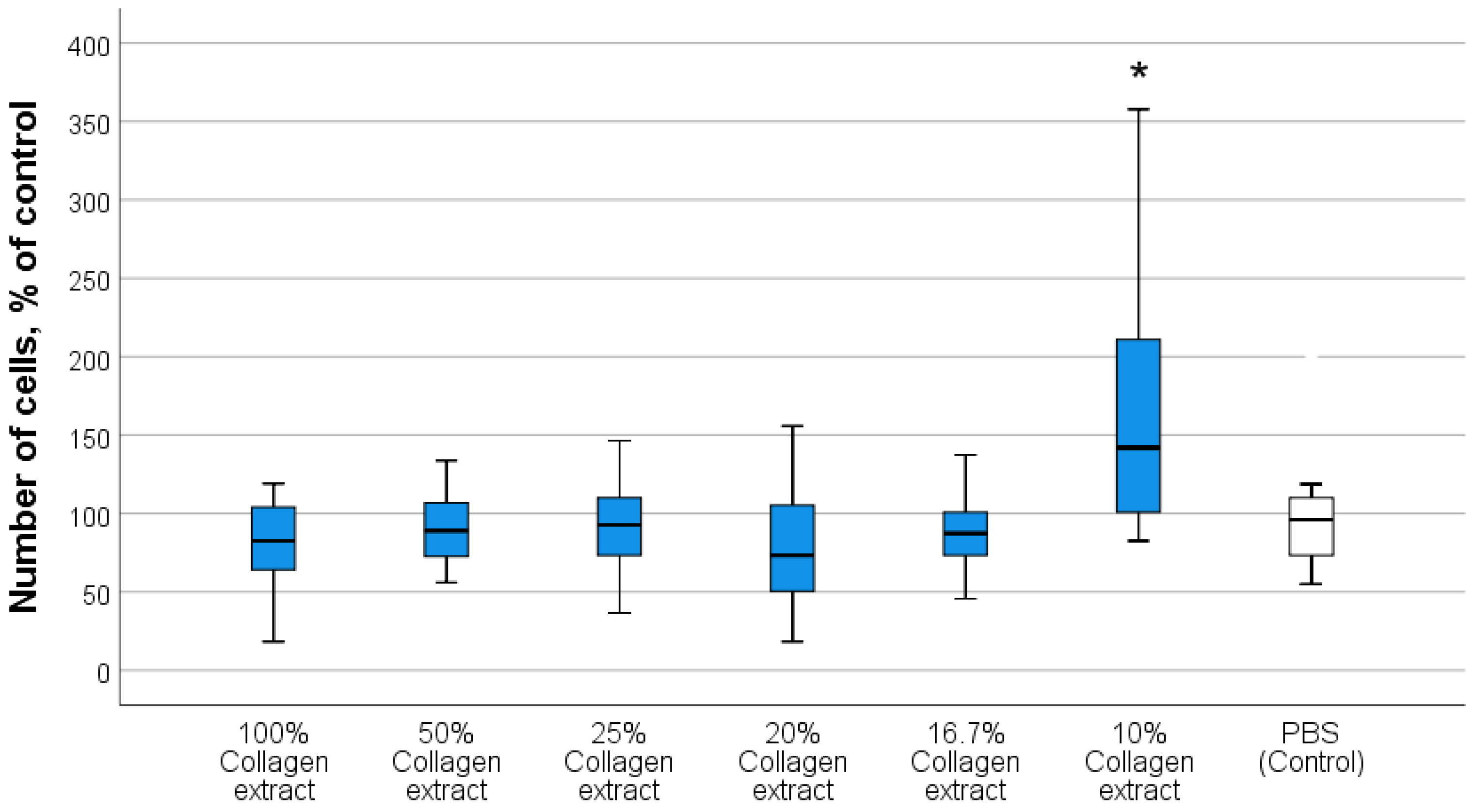

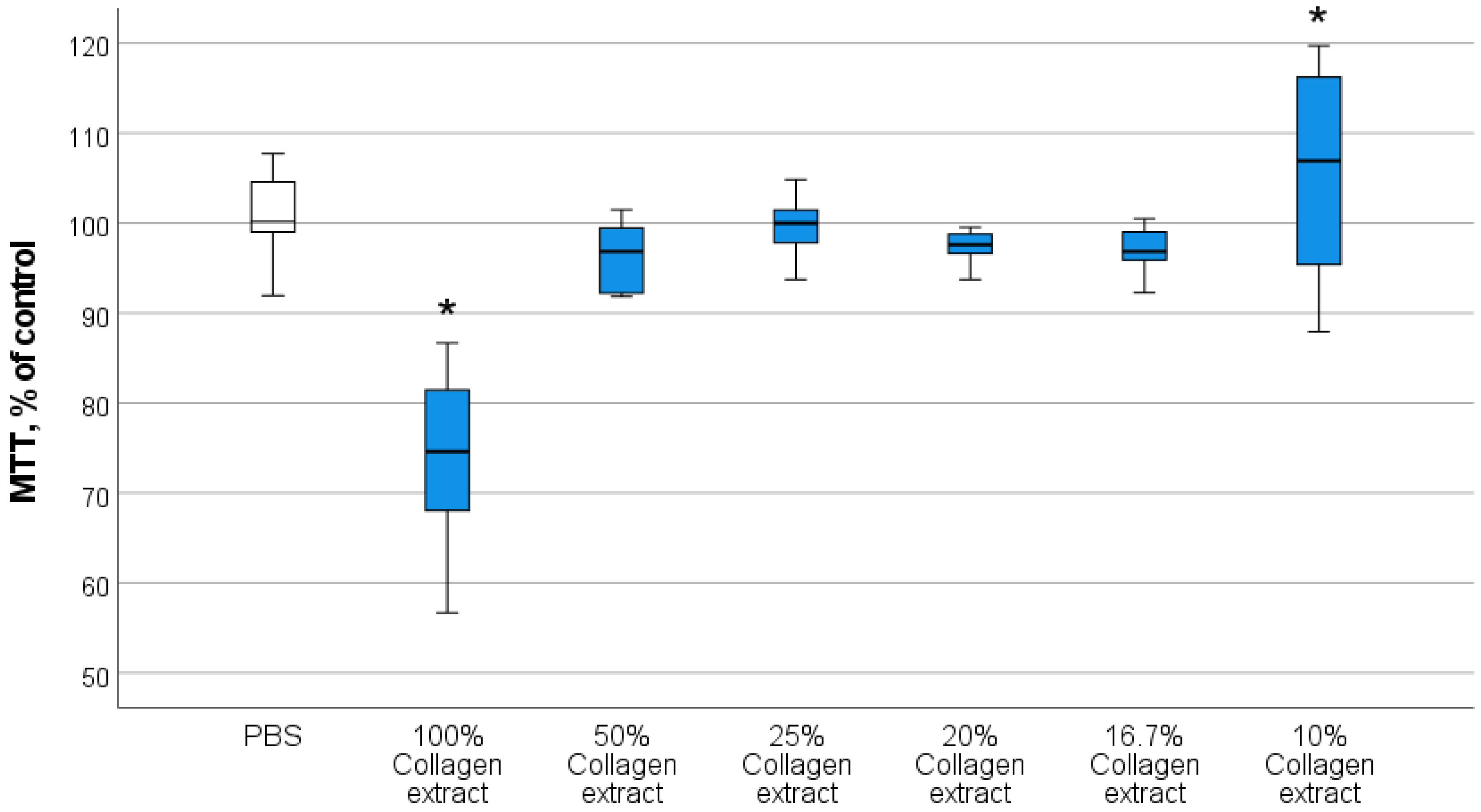

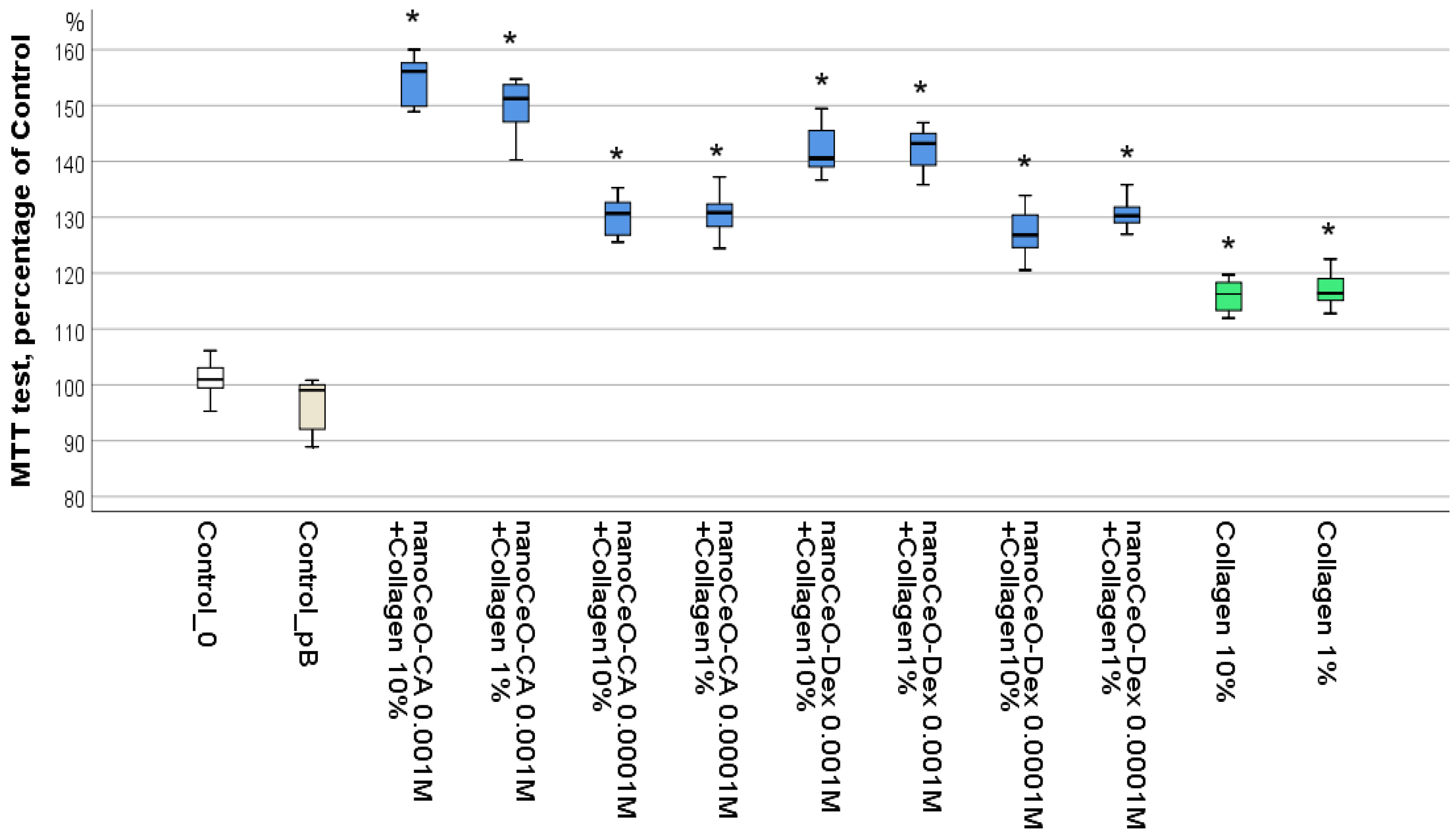

3.2.1. Optimal Concentrations of Composite Components Stimulating Human Fibroblast Activity

3.2.2. Investigation of the Effect of Collagen–Nanocerium Composites on Proliferative and Metabolic Cell Activity

3.3. Results of the Bacterial Biosensor Studies

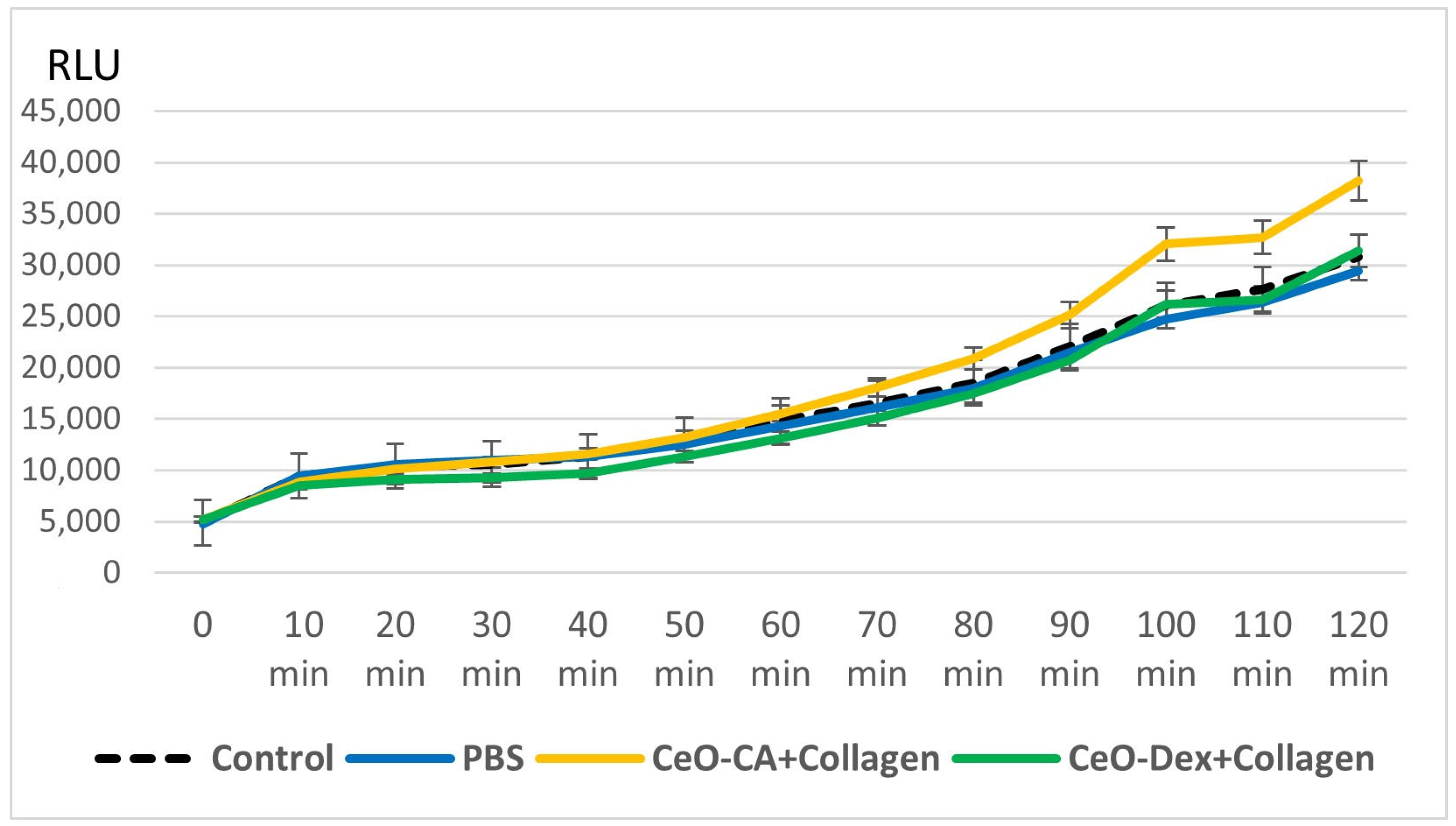

3.3.1. Results of Collagen–Nanocerium Composites Testing for General Toxicity on the E. coli MG 1655 pXen7 Biosensor

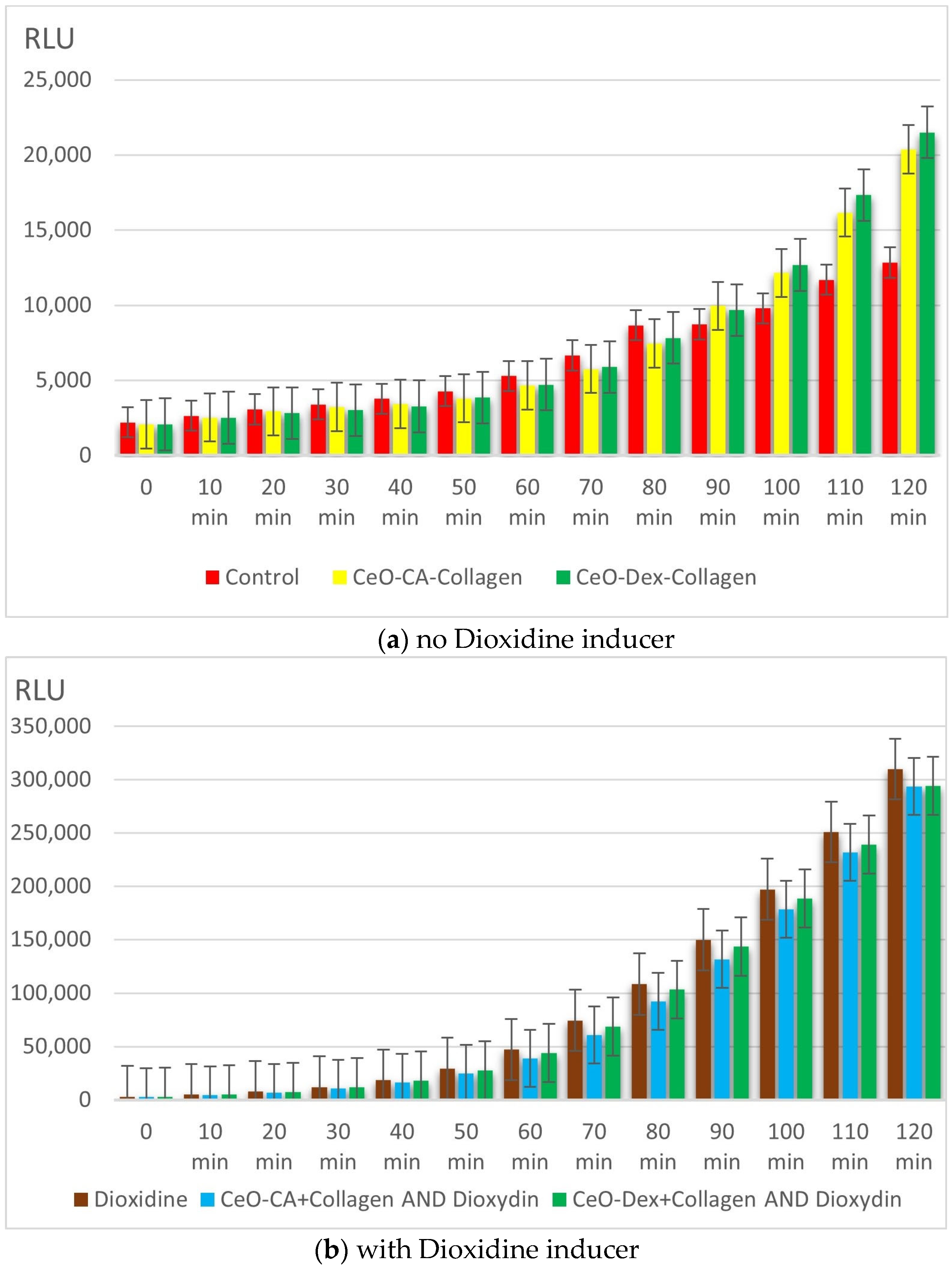

3.3.2. Antigenotoxic and Promutagenic Activity of Collagen–Nanocerium Composites on the E. coli MG1655 pRecA Biosensor

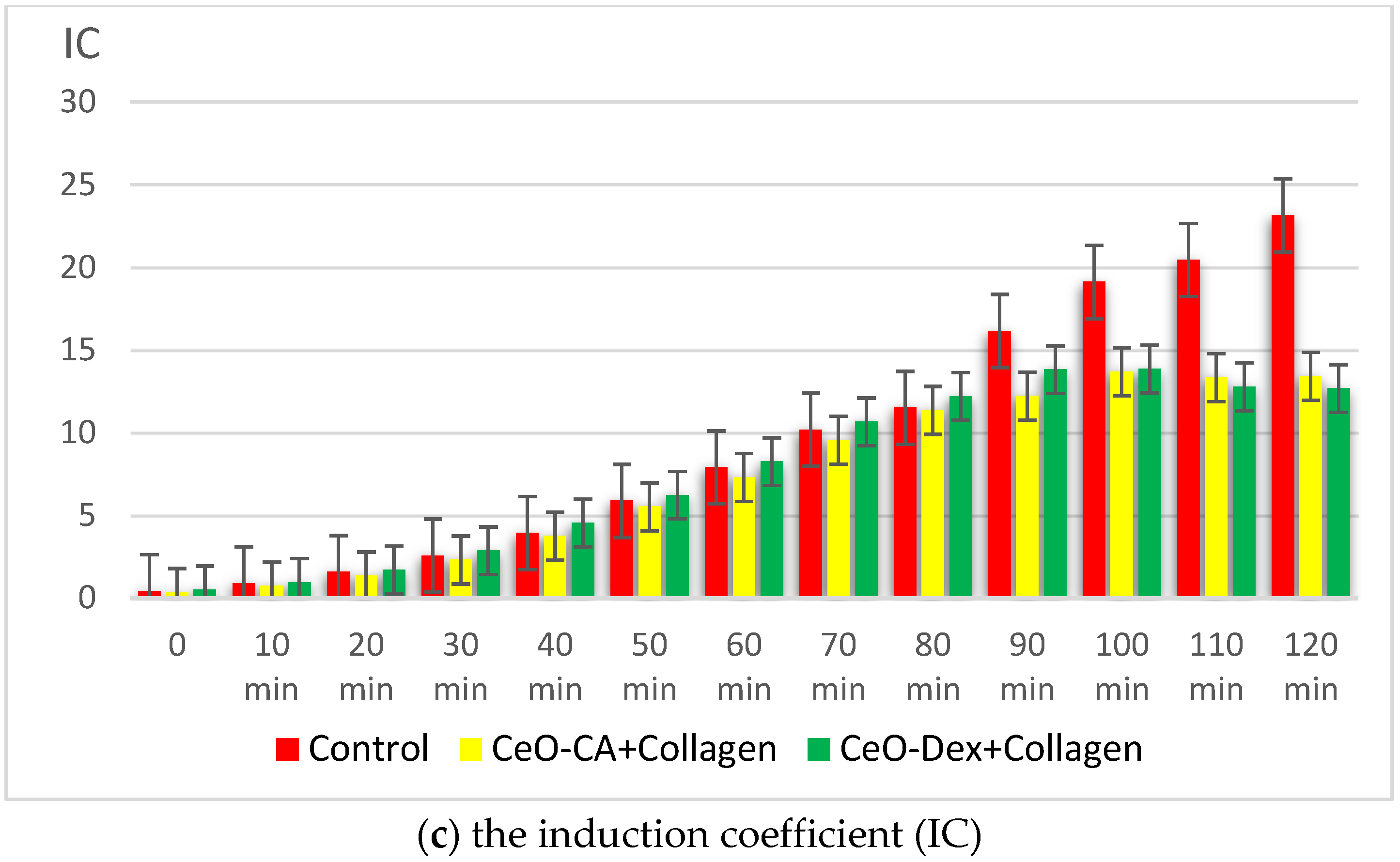

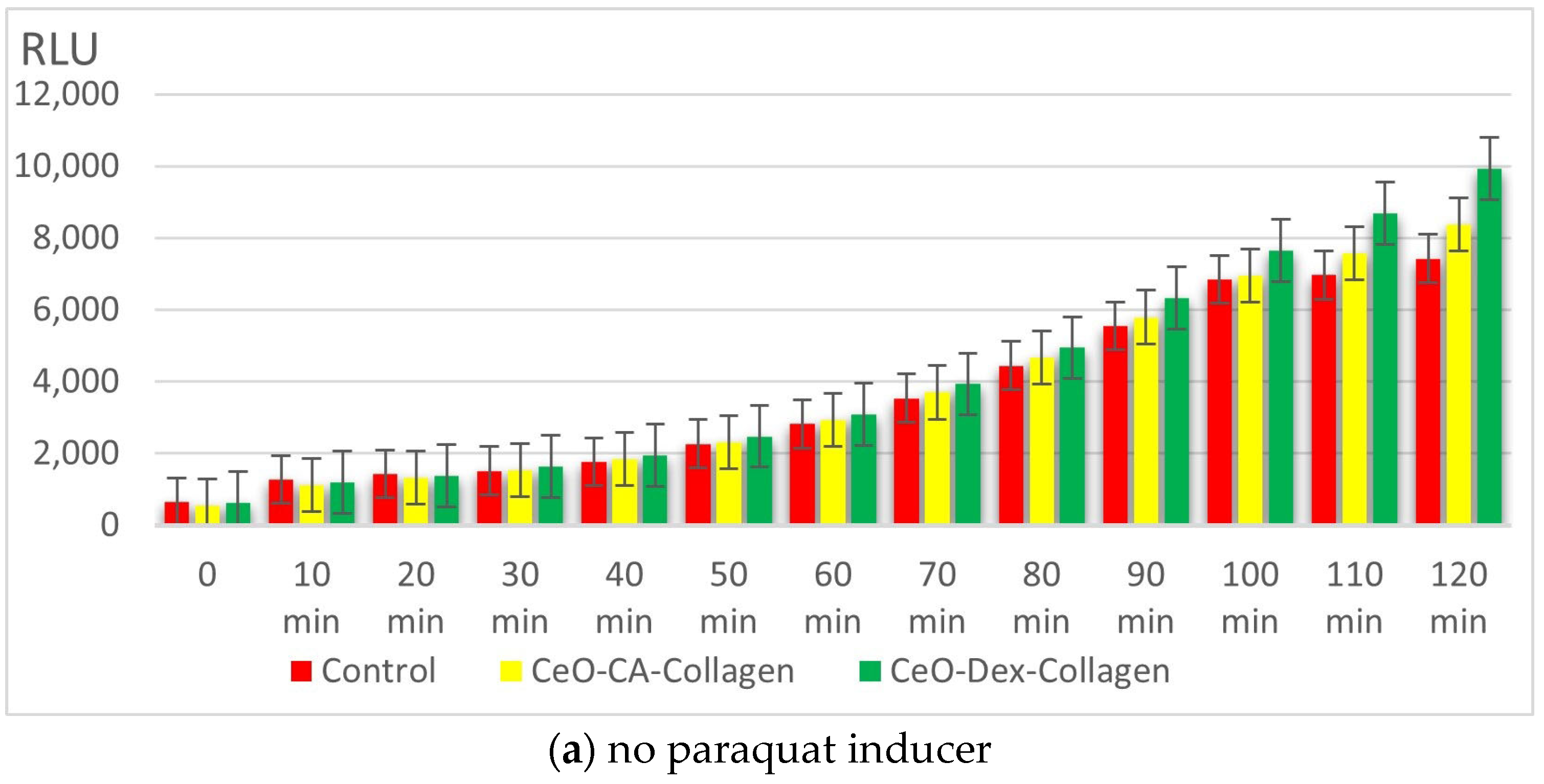

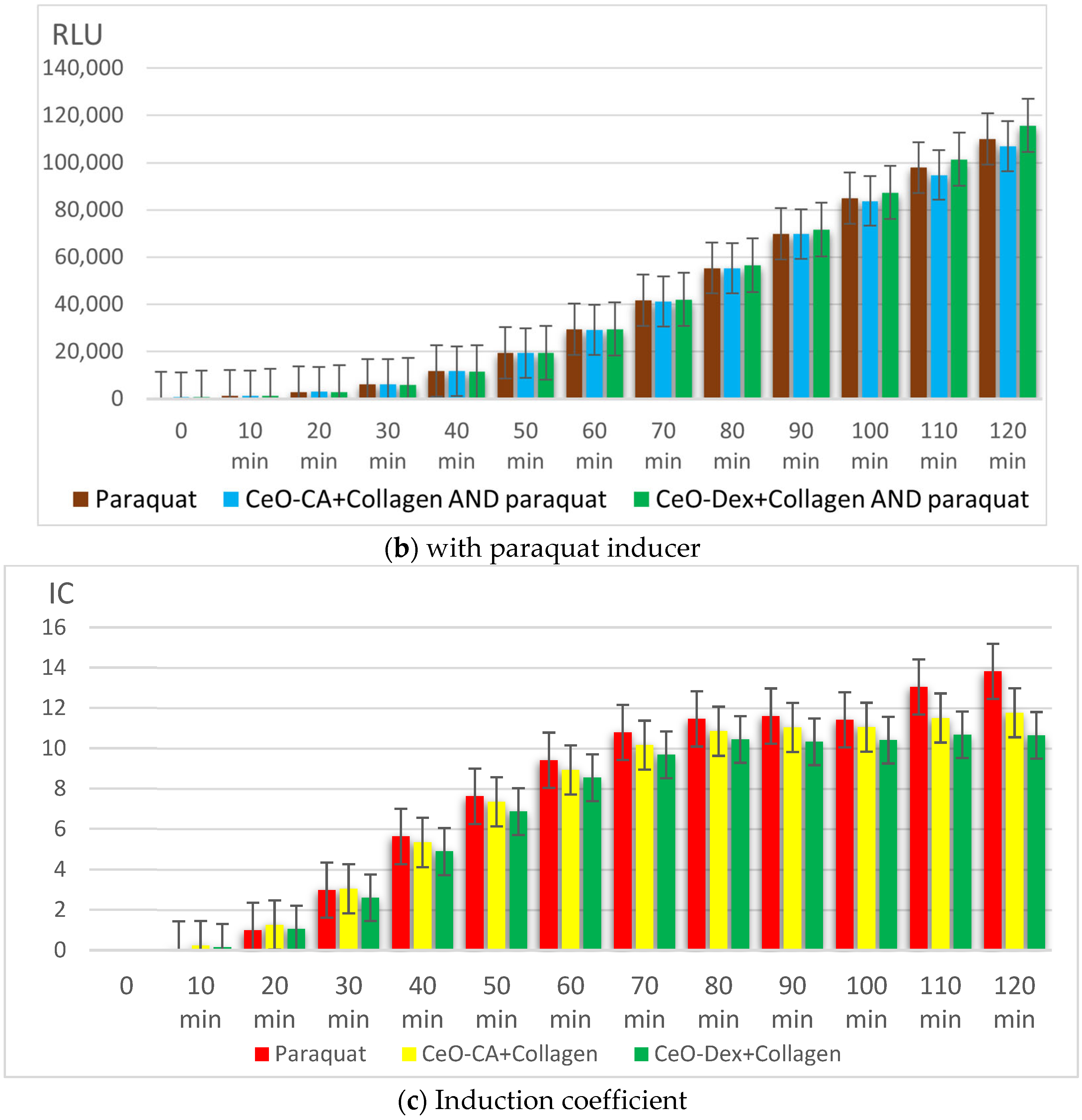

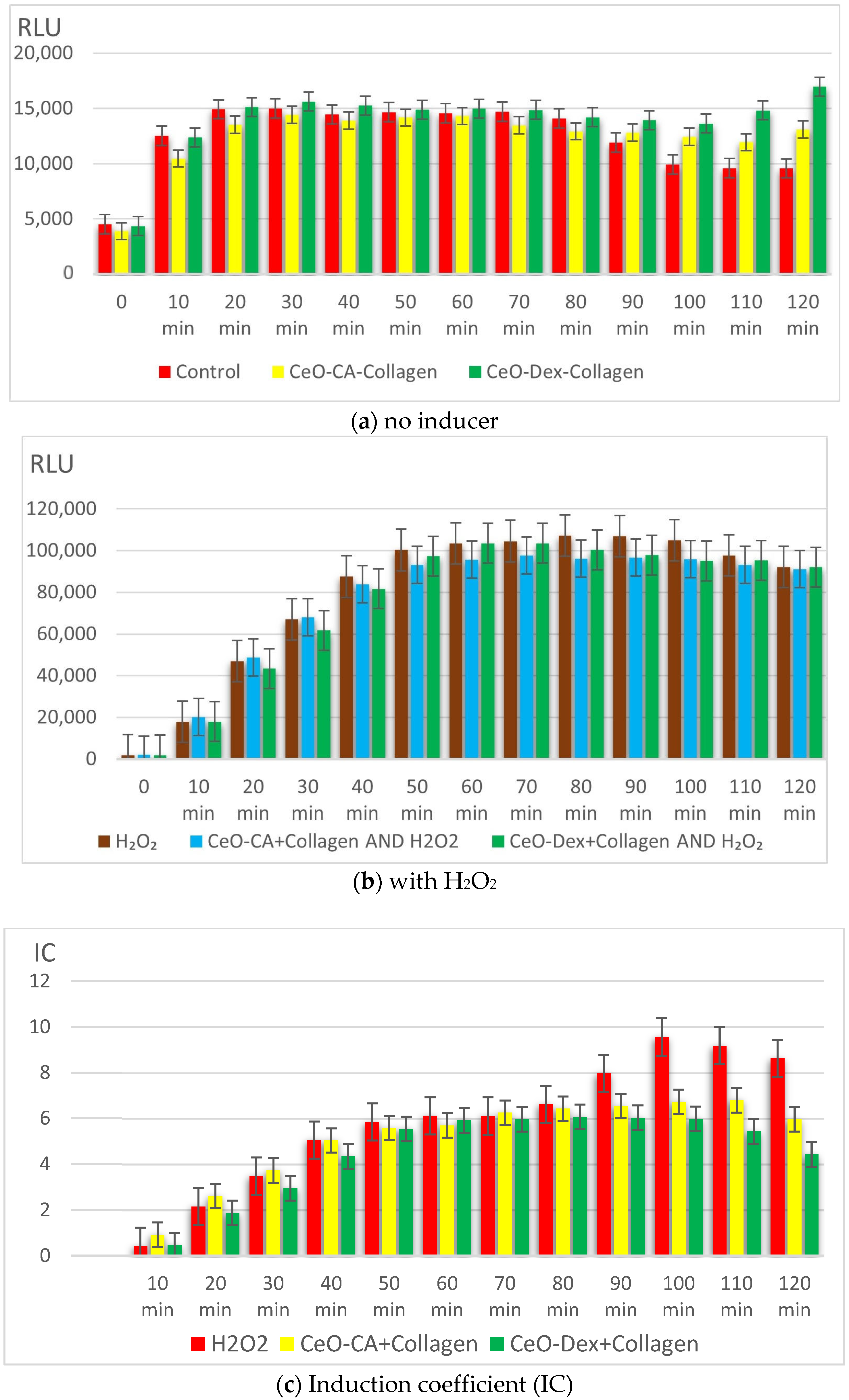

3.3.3. Redox Activity of Collagen–Nanocerium Composites on the Bioluminescent Biosensors E. coli MG1655 pSoxS-lux and pKatG

3.4. Efficacy of Drug Prototypes Based on Cerium Dioxide Nanoparticles and Collagen Biopolymer in an Animal Model of Acute Full-Thickness Skin Wound

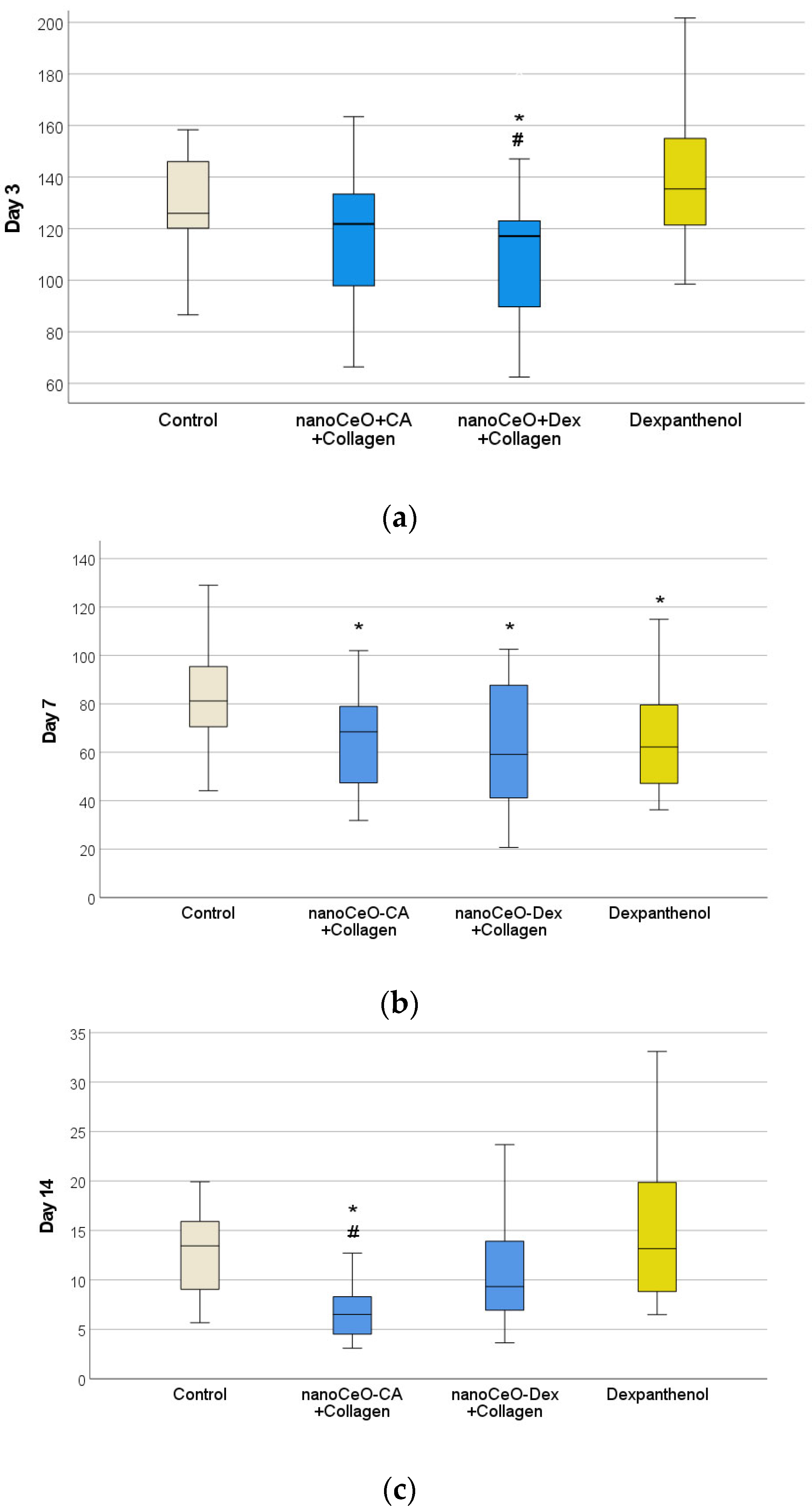

3.4.1. Wound-Healing Dynamics

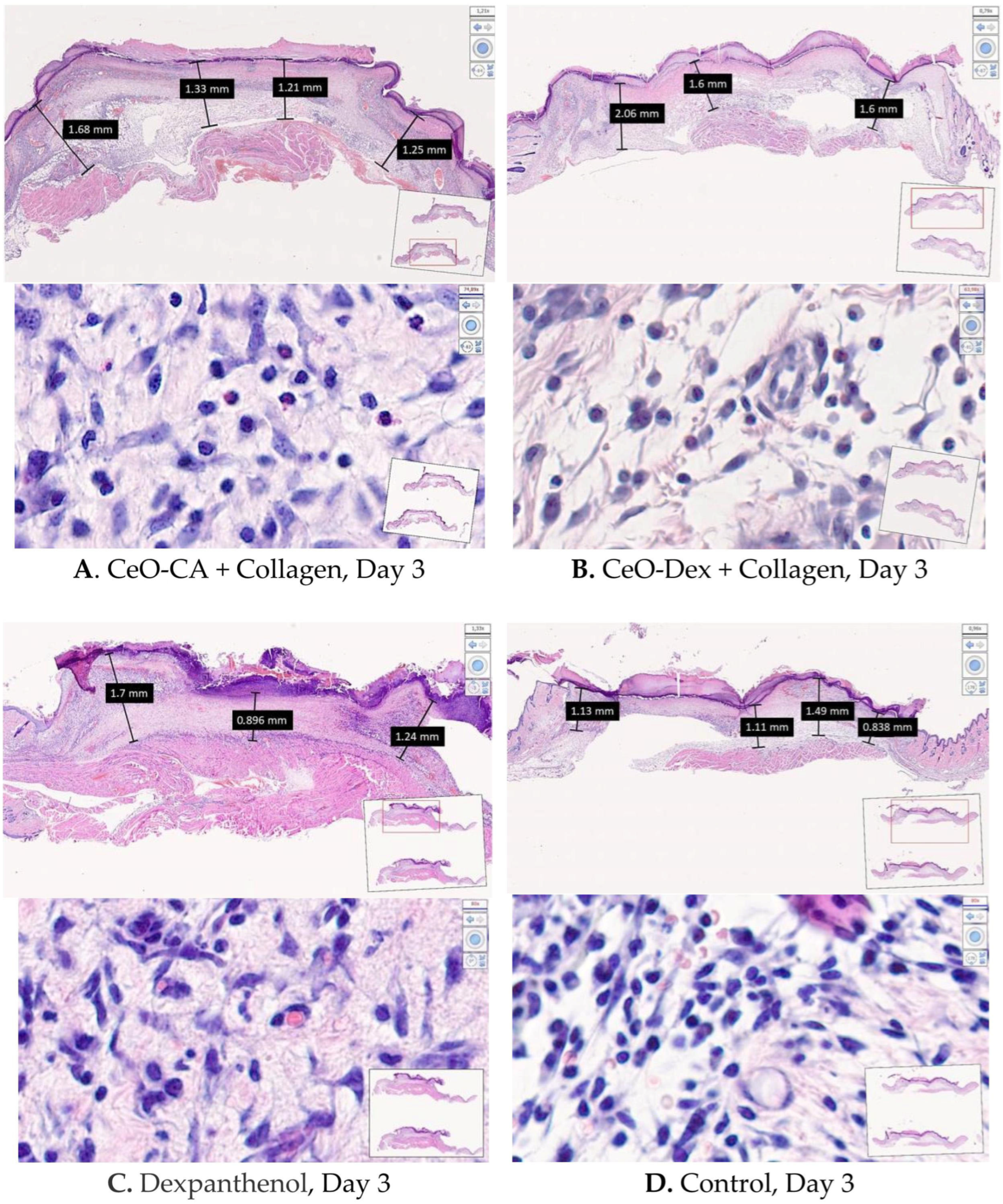

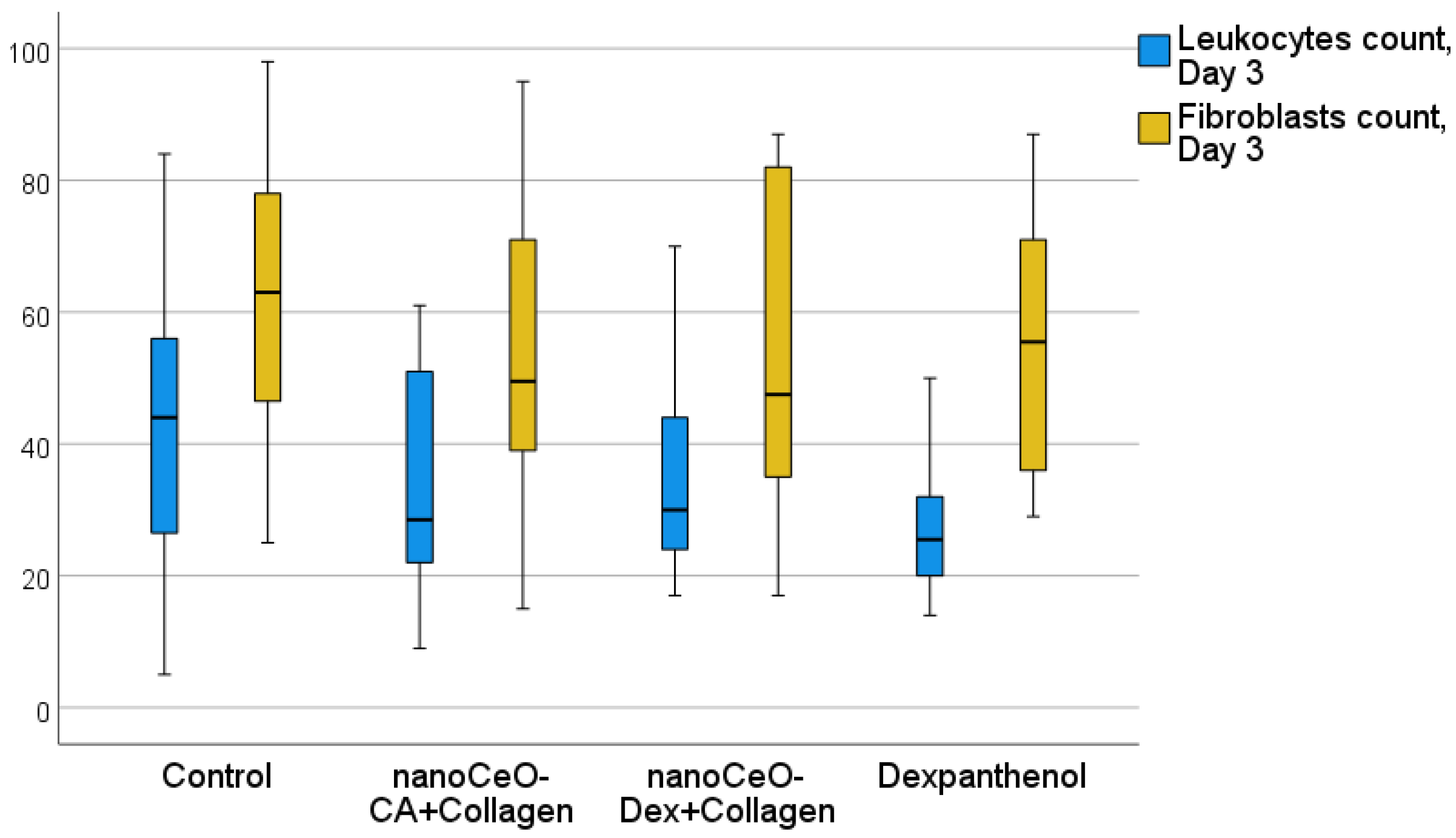

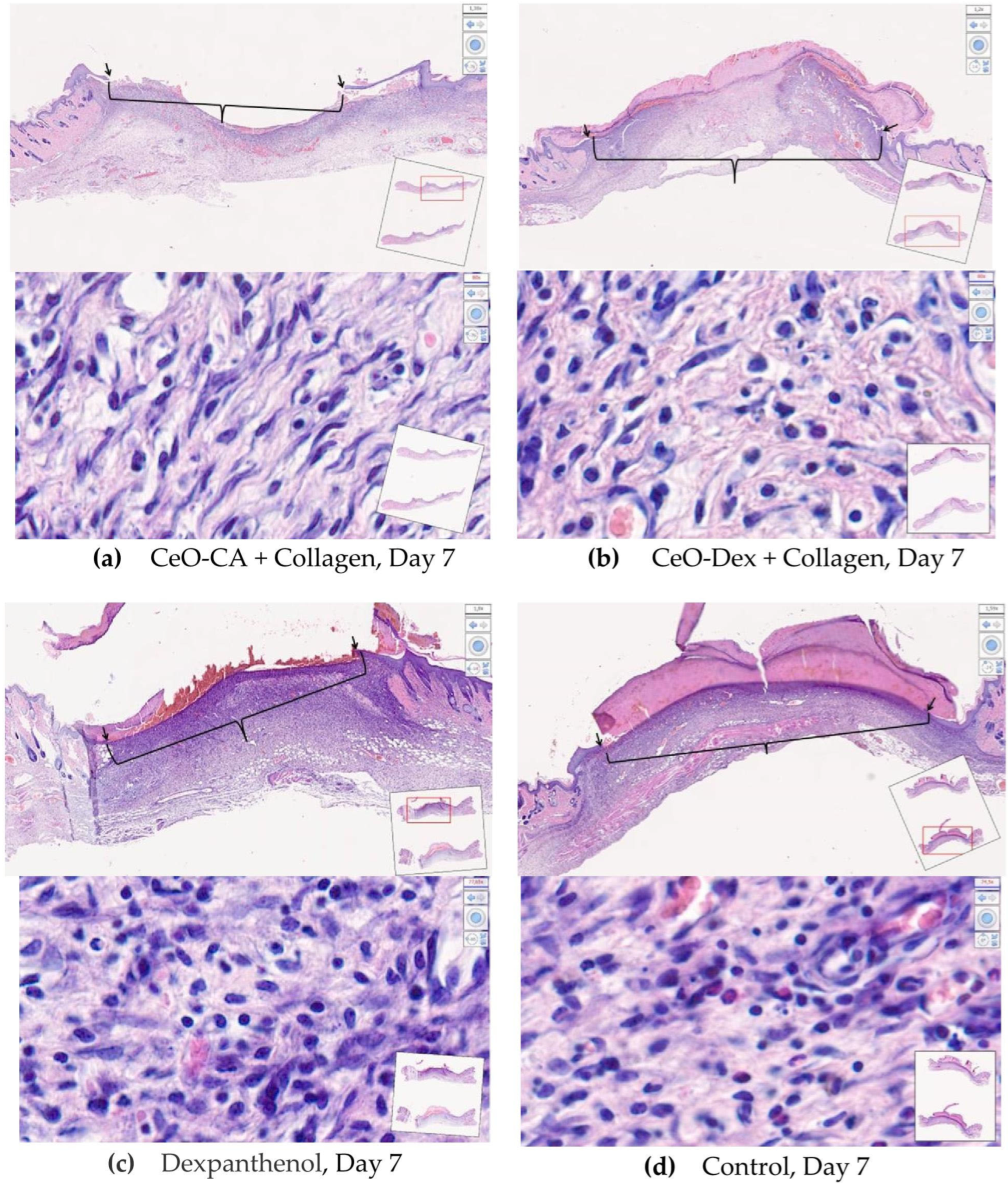

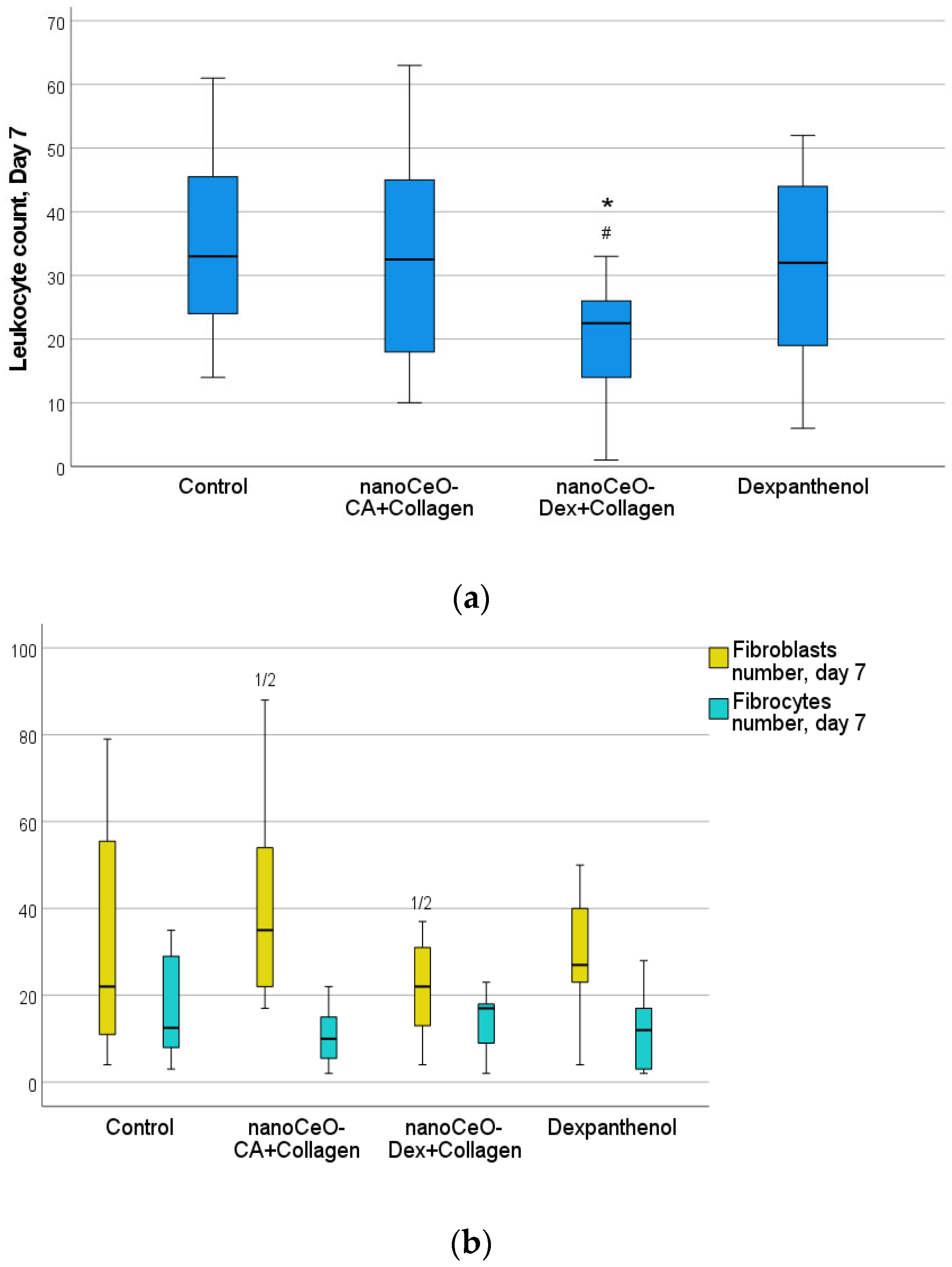

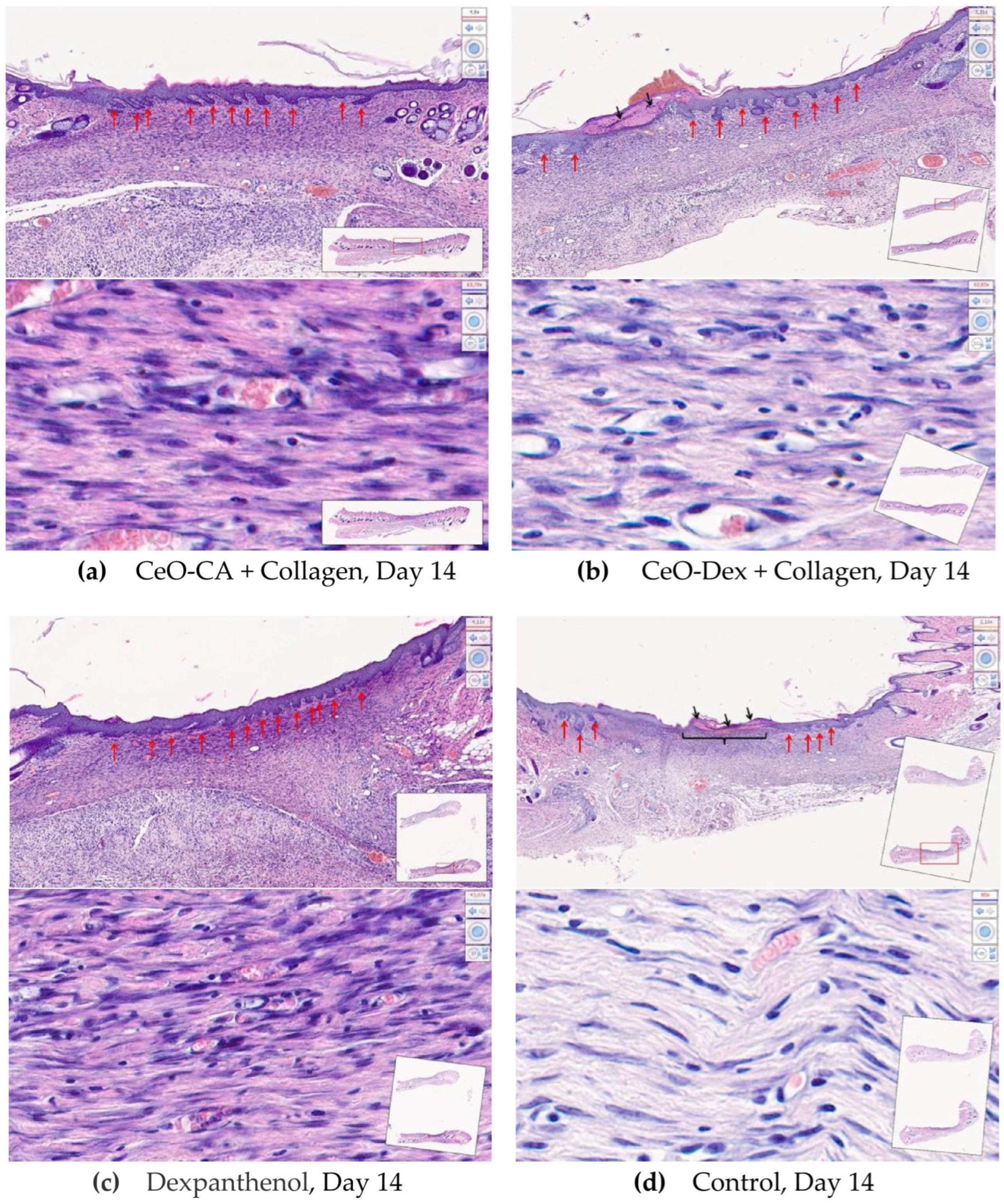

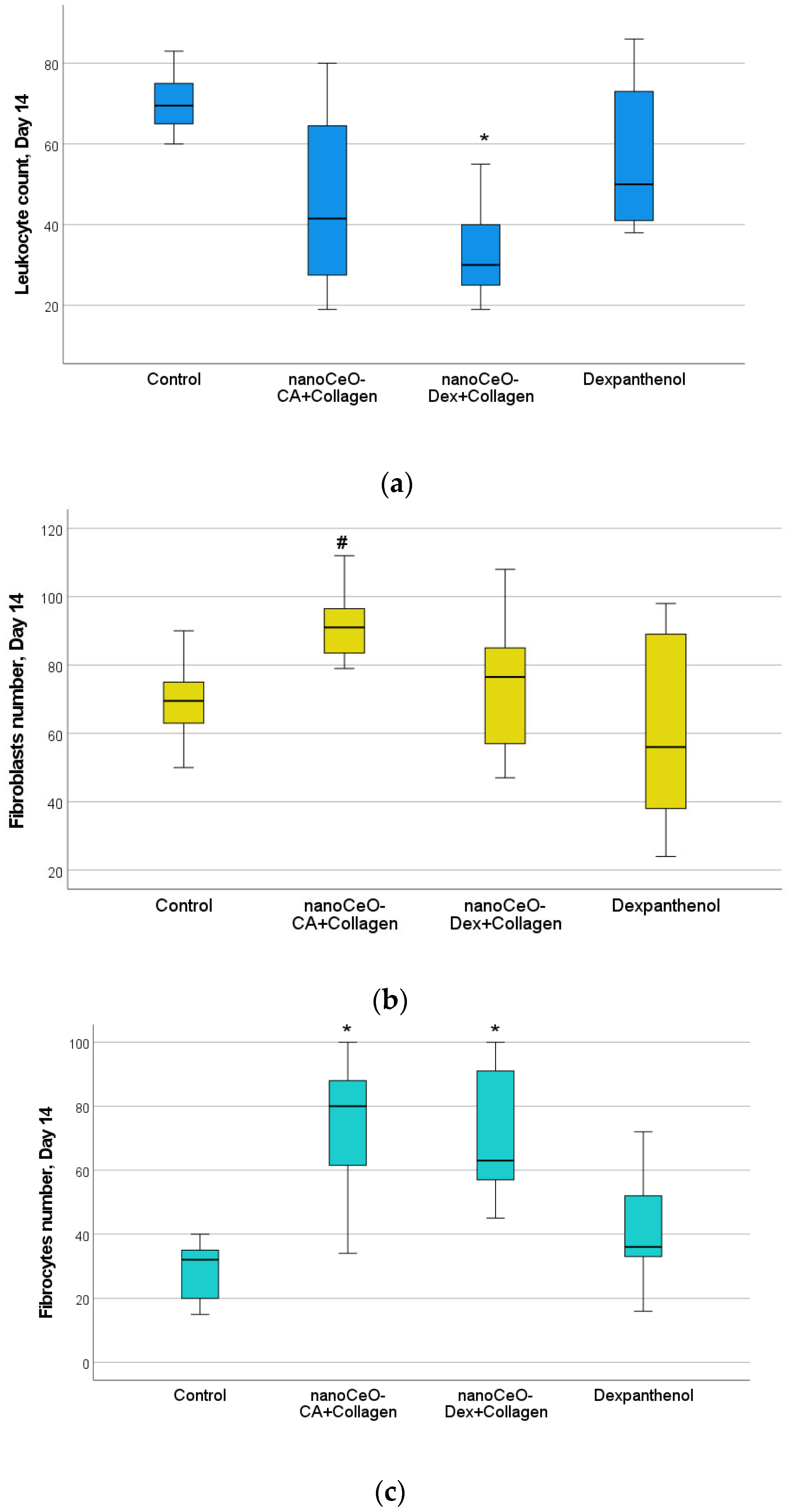

3.4.2. Histological and Morphometric Examination of Wound Tissues

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- A new protein-nanocerium composite based on collagen and cerium dioxide nanoparticles coated with a polysaccharide (dextran) or a carboxylic acid (citric acid) was developed. These composites possess novel pharmacological properties, including regenerative and antioxidant effects.

- The cell culture studies allowed for the selection of the most active and safe collagen-CeO2 complex composites − CeO (10−3 M)-CA + Collagen (10%) and CeO (10−3 M)-Dextran + Collagen (10%), which significantly stimulated fibroblasts by 1.5 and 1.4 times (by 42–55%), respectively, after just 72 h of co-incubation.

- Studies on bacterial lux-biosensors have provided data on induction and protective activity for parameters such as general toxicity, antioxidant, pro-oxidant, antigenotoxic, and promutagenic activities. It was established that the nanocomposites did not demonstrate a toxic effect but possessed antigenotoxicity at a level of up to 45% as well as antioxidant activity against H2O2 (up to 49% in the CeO-Dex + Collagen group and 31% in the CeO-CA + Collagen group), thus exhibiting a protective effect.

- Accelerated wound healing was demonstrated, starting from day 3 and continuing until day 14 (up to complete epithelialization), owing to faster ECM formation and early skin cell differentiation.

- In models of acute skin wounds, the regenerative effect of the nanocomposites was demonstrated and exceeded that of not only the control group but also some clinical drugs, which are routinely used for skin wound healing management.

Limitations and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCE | Collagen-Containing Extract |

| ECM | extracellular matrix |

| E. coli | Escherichia coli |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| IC | induction coefficient |

| OD | optical density |

| PBS | phosphate-buffered saline |

| RLU | relative light units |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SAR | superoxide anion radical |

References

- Schneider, C.; Stratman, S.; Kirsner, R.S. Lower Extremity Ulcers. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 105, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, K.A.; Mills, J.L.; Armstrong, D.G.; Conte, M.S.; Kirsner, R.S.; Minc, S.D.; Plutzky, J.; Southerland, K.W.; Tomic-Canic, M.; American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; et al. Current Status and Principles for the Treatment and Prevention of Diabetic Foot Ulcers in the Cardiovascular Patient Population: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2024, 149, e232–e253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, J.P.; Hedayati, N. Challenges of treating mixed arterial-venous disease of lower extremities. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2021, 62, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter-Riesch, B. The Diabetic Foot: The Never-Ending Challenge. Endocr. Dev. 2016, 31, 108–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayala, B.Z. Skin Ulcers: Prevention and Diagnosis of Pressure, Venous Leg, and Arterial Ulcers. FP Essent. 2020, 499, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Deinsberger, J.; Moschitz, I.; Marquart, E.; Manz-Varga, A.K.; Gschwandtner, M.E.; Brugger, J.; Rinner, C.; Böhler, K.; Tschandl, P.; Weber, B. Development of a localization-based algorithm for the prediction of leg ulcer etiology. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2023, 21, 1339–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garavello, A.; Fransvea, P.; Gilardi, S.; Fiamma, P. Venous ulcers: Look at the patient, not at the ulcer! Risk factors and comorbid conditions in venous ulcers of lower limbs. Minerva Cardiol. Angiol. 2023, 71, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayrovitz, H.N.; Wong, S.; Mancuso, C. Venous, Arterial, and Neuropathic Leg Ulcers with Emphasis on the Geriatric Population. Cureus 2023, 25, e38123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjunath, K.N.; Nisarga, V.; Venkatesh, M.S.; Sanmathi, P.; Shanthkumar, S. Efficacy of collagen and elastin matrix in the treatment of complex lower extremity wounds. Acta Chir. Plast. 2024, 66, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosti, J.K.; Chandler, L.A. Intervention with Formulated Collagen Gel for Chronic Heel Pressure Ulcers in Older Adults with Diabetes. Adv. Skin Wound Care 2015, 28, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiser, I.; Tamir, E.; Kaufman, H.; Keren, E.; Avshalom, S.; Klein, D.; Heller, L.; Shapira, E. A Novel Recombinant Human Collagen-based Flowable Matrix for Chronic Lower Limb Wound Management: First Results of a Clinical Trial. Wounds 2019, 31, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Silina, E.V.; Stupin, V.A.; Zolotareva, L.S.; Komarov, A.N. Native collagen application in clinical practice for chronic wounds treatment. Pirogov Russ. J. Surg. 2017, 9, 78–84. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stupin, V.A.; Silina, E.V.; Gorskij, V.A.; Gorjunov, S.V.; Zhidkih, S.Y.; Komarov, A.N.; Sivkov, A.S.; Gabitov, R.B.; Zolotareva, L.S.; Sinel’nikova, T.G.; et al. Efficacy and safety of collagen biomaterial local application in complex treatment of the diabetic foot syndrome (final results of the multicenter randomised study). Khirurgiia 2018, 6, 91–100. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silina, E.V.; Manturova, N.E.; Litvitskiy, P.F.; Stupin, V.A. Comparative Analysis of the Effectiveness of Some Biological Injected Wound Healing Stimulators and Criteria for Its Evaluation. Drug. Des. Devel. Ther. 2020, 14, 4869–4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, H.R.; Emadi, E.; Hamidi Alamdari, D. Limb Saving with a Combination of Allogenic Platelets-Rich Plasma, Fibrin Glue, and Collagen Matrix in an Open Fracture of the Tibia: A Case Report. Arch. Bone Jt. Surg. 2023, 11, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cwajda-Białasik, J.; Mościcka, P.; Szewczyk, M.T.; Hojan-Jezierska, D.; Kawałkiewicz, W.; Majewska, A.; Janus-Kubiak, M.; Kubisz, L.; Jawieñ, A. Venous leg ulcers treated with fish collagen gel in a 12-week randomized single-centre study. Postepy. Dermatol. Alergol. 2022, 39, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Rai, V.K.; Narang, R.K.; Markandeywar, T.S. Collagen-based formulations for wound healing: A literature review. Life Sci. 2022, 290, 120096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Dong, J.; Du, R.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, P. Collagen study advances for photoaging skin. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2024, 40, e12931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, H.L. Extracellular Matrix and Ageing. Subcell. Biochem. 2018, 90, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, V.; Sekaran, S.; Dhanasekaran, A.; Warrier, S. Type 1 collagen: Synthesis, structure and key functions in bone mineralization. Differentiation 2024, 136, 100757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Añazco, C.; Ojeda, P.G.; Guerrero-Wyss, M. Common Beans as a Source of Amino Acids and Cofactors for Collagen Biosynthesis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, T.T.; Tey, J.Y.; Soon, K.S.; Woo, K.K. Utilizing Fish Skin of Ikan Belida (Notopterus lopis) as a Source of Collagen: Production and Rheology Properties. Mar. Drugs. 2022, 20, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila Rodríguez, M.I.; Rodríguez Barroso, L.G.; Sánchez, M.L. Collagen: A review on its sources and potential cosmetic applications. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2018, 17, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Wu, G. Roles of dietary glycine, proline, and hydroxyproline in collagen synthesis and animal growth. Amino Acids 2018, 50, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrajabian, M.H.; Sun, W. Mechanism of Action of Collagen and Epidermal Growth Factor: A Review on Theory and Research Methods. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2024, 24, 453–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.M.; Wei, C.Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, L.; Lu, L.; Qi, F.Z. M2-polarized macrophages mediate wound healing by regulating connective tissue growth factor via AKT, ERK1/2, and STAT3 signaling pathways. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 6443–6456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maksimova, A.A.; Shevela, E.Y.; Sakhno, L.V.; Tikhonova, M.A.; Ostanin, A.A.; Chernykh, E.R. Influence of Secretome of Different Functional Phenotypes of Macrophages on Proliferation, Differentiation, and Collagen-Producing Activity of Dermal Fibroblasts In Vitro. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2021, 171, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, D.; Chen, R.; Li, H.; Zheng, J.; Fu, W.; Shi, Z.; You, C.; Yang, M.; Ma, L. Reduced M2 macrophages and adventitia collagen dampen the structural integrity of blood blister-like aneurysms and induce preoperative rerupture. Cell Prolif. 2022, 55, e13175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesketh, M.; Sahin, K.B.; West, Z.E.; Murraym, R.Z. Macrophage Phenotypes Regulate Scar Formation and Chronic Wound Healing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.M.; Batsukh, S.; Sung, M.J.; Lim, T.H.; Lee, M.H.; Son, K.H.; Byun, K. Poly-L-Lactic Acid Fillers Improved Dermal Collagen Synthesis by Modulating M2 Macrophage Polarization in Aged Animal Skin. Cells 2023, 12, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motz, K.; Lina, I.; Murphy, M.K.; Drake, V.; Davis, R.; Tsai, H.W.; Feeley, M.; Yin, L.X.; Ding, D.; Hillel, A. M2 Macrophages Promote Collagen Expression and Synthesis in Laryngotracheal Stenosis Fibroblasts. Laryngoscope 2021, 131, e346–e353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccarone, R.; Tisi, A.; Passacantando, M.; Ciancaglini, M. Ophthalmic Applications of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 36, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadidi, H.; Hooshmand, S.; Ahmadabadi, A.; Javad Hosseini, S.; Baino, F.; Vatanpour, M.; Kargozar, S. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles (Nanoceria): Hopes in Soft Tissue Engineering. Molecules 2020, 25, 4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casals, E.; Zeng, M.; Parra-Robert, M.; Fernández-Varo, G.; Morales-Ruiz, M.; Jiménez, W.; Puntes, V.; Casals, G. Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles: Advances in Biodistribution, Toxicity, and Preclinical Exploration. Small 2020, 16, e1907322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charbgoo, F.; Ahmad, M.B.; Darroudi, M. Cerium oxide nanoparticles: Green synthesis and biological applications. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 1401–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humaira; Bukhari, S.A.R.; Shakir, H.A.; Khan, M.; Saeed, S.; Ahmad, I.; Irfan, M. Biosynthesized Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles CeO2NPs: Recent Progress and Medical Applications. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2023, 24, 766–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnatskaya, V.; Shlapa, Y.; Yushko, L.; Shton, I.; Solopan, S.; Ostrovska, G.; Kalachniuk, L.; Negelia, A.; Garmanchuk, L.; Prokopenko, I.; et al. Biological activity of cerium dioxide nanoparticles. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2020, 108, 1703–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manturova, N.E.; Stupin, V.A.; Silina, E.V. Cerium oxide nanoparticles for surgery, plastic surgery and aesthetic medicine. Plast. Surg. Aesthetic Med. 2023, 3, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosrati, H.; Heydari, M.; Khodaei, M. Cerium oxide nanoparticles: Synthesis methods and applications in wound healing. Mater. Today Bio. 2023, 23, 100823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silina, E.V.; Manturova, N.E.; Erokhina, A.G.; Shatokhina, E.A.; Stupin, V.A. Nanomaterials based on cerium oxide nanoparticles for wound regeneration: A literature review. Russ. J. Transplantology Artif. Organs 2024, 26, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xu, J.; Sun, G.; Cheng, X.; An, Y.; Yao, X.; Nie, G.; Zhang, Y. Enteric-coated cerium dioxide nanoparticles for effective inflammatory bowel disease treatment by regulating the redox balance and gut microbiome. Biomaterials 2025, 314, 122822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Ojeda, S.; Marchio, P.; Rueda, C.; Suarez, A.; Garcia, H.; Victor, V.M.; Juez, M.; Martin-Gonzalez, I.; Vila, J.M.; Mauricio, M.D. Cerium dioxide nanoparticles modulate antioxidant defences and change vascular response in the human saphenous vein. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 193, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, N.; Manna, P.; Das, J. Synthesis and biomedical applications of nanoceria, a redox active nanoparticle. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2019, 17, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, K.; Dutta, K.; Chatterjee, A.; Sarkar, J.; Das, D.; Prasad, A.; Chattopadhyay, D.; Acharya, K.; Das, M.; Verma, S.K.; et al. Nanotherapeutic potential of antibacterial folic acid-functionalized nanoceria for wound-healing applications. Nanomedicine 2023, 18, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmorshdy Elsaeed Mohammed Elmorshdy, S.; Ahmed Shaker, G.; Eldken, Z.H.; Salem, M.A.; Awadalla, A.; Shakour, H.M.A.; Elmahdy El Hosiny Sarhan, M.; Hussein, A.M. Impact of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles on Metabolic, Apoptotic, Autophagic and Antioxidant Changes in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiomyopathy: Possible Underlying Mechanisms. Rep. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2023, 12, 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Li, S.; Ma, X.; Xue, T.; Shen, F.; Ru, Y.; Jiang, J.; Kuai, L.; Li, B.; Zhao, H.; et al. Cerium oxide nanoparticles in diabetic foot ulcer management: Advances, limitations, and future directions. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2023, 231, 113535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Han, Z.; Wang, T.; Ma, C.; Li, H.; Lei, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pei, Z.; Liu, Z.; et al. Cerium oxide nanoparticles with antioxidative neurorestoration for ischemic stroke. Biomaterials 2022, 291, 121904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmanan, M.; Saini, M.; Nune, M. Exploring the innovative application of cerium oxide nanoparticles for addressing oxidative stress in ovarian tissue regeneration. J. Ovarian Res. 2024, 17, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenkenschuh, E.; Friess, W. Freeze-drying of nanoparticles: How to overcome colloidal instability by formulation and process optimization. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2021, 165, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Ryan, K.M.; Padrela, L. Production and isolation of pharmaceutical drug nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 603, 120708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titova, S.A.; Kruglova, M.P.; Stupin, V.A.; Manturova, N.E.; Achar, R.R.; Deshpande, G.; Parfenov, V.A.; Silina, E.V. Excipients for Cerium Dioxide Nanoparticle Stabilization in the Perspective of Biomedical Applications. Molecules 2025, 30, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevastianov, V.I.; Basok, Y.B. (Eds.) Biomimetics of Extracellular Matrices for Cell and Tissue Engineered Medical Products; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar, S.H.; Di Luca, A.; Zaccaria, S.; Baaijens, F.P.T.; Bouten, C.V.C.; Dankers, P.Y.W. Dual Electrospun Supramolecular Polymer Systems for Selective Cell Migration. Macromol. Biosci. 2018, 18, e1800004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.K. From fundamental supramolecular chemistry to self-assembled nanomaterials and medicines and back again—How Sam inspired SAMul. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 4743–4760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Li, B.; Xie, M.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, H.; Qiu, L.; Huang, L.; et al. Triple-crosslinked double-network alginate/dextran/dendrimer hydrogel with tunable mechanical and adhesive properties: A potential candidate for sutureless keratoplasty. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 344, 122538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piras, C.C.; Smith, D.K. Multicomponent polysaccharide alginate-based bioinks. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 8171–8188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silina, E.V.; Ivanova, O.S.; Manturova, N.E.; Medvedeva, O.A.; Shevchenko, A.V.; Vorsina, E.S.; Achar, R.R.; Parfenov, V.A.; Stupin, V.A. Antimicrobial Activity of Citrate-Coated Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silina, E.V.; Stupin, V.A.; Manturova, N.E.; Ivanova, O.S.; Popov, A.L.; Mysina, E.A.; Artyushkova, E.B.; Kryukov, A.A.; Dodonova, S.A.; Kruglova, M.P.; et al. Influence of the Synthesis Scheme of Nanocrystalline Cerium Oxide and Its Concentration on the Biological Activity of Cells Providing Wound Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silina, E.V.; Manturova, N.E.; Ivanova, O.S.; Baranchikov, A.E.; Artyushkova, E.B.; Medvedeva, O.A.; Kryukov, A.A.; Dodonova, S.A.; Gladchenko, M.P.; Vorsina, E.S.; et al. Cerium Dioxide–Dextran Nanocomposites in the Development of a Medical Product for Wound Healing: Physical, Chemical and Biomedical Characteristics. Molecules 2024, 29, 2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, A.; Hafeez, S.; Habibovic, P.; Baker, M.; van Rijt, S. Extracellular matrix mimetic supramolecular hydrogels reinforced with covalent crosslinked mesoporous silica nanoparticles. J. Mater. Chem. B 2024, 12, 12577–12588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Lu, L.; Wu, H.; Hu, J.; Wang, F.; Zhang, B.; Wang, J.; Yang, X.; Luo, R.; et al. Tailored extracellular matrix-mimetic coating facilitates reendothelialization and tissue healing of cardiac occluders. Biomaterials 2025, 313, 122769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Li, M.; Wu, H.; Qin, Y.; Wang, J.; Xu, K.; Luo, R.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. An extracellular matrix-mimetic coating with dual bionics for cardiovascular stents. Regen. Biomater. 2023, 10, rbad055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevastyanov, V.P.; Perova, N.V. Injectable Heterogeneous Biopolymer Hydrogel for Replacement and Regenerative Surgery and a Method for Its Production. Russian Federation Patent RU 2433828 C1, 20 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Silina, E.V.; Stupin, V.A.; Manturova, N.E.; Chuvilina, E.L.; Gasanov, A.A.; Ostrovskaya, A.A.; Andreeva, O.I.; Tabachkova, N.Y.; Abakumov, M.A.; Nikitin, A.A.; et al. Development of Technology for the Synthesis of Nanocrystalline Cerium Oxide Under Production Conditions with the Best Regenerative Activity and Biocompatibility for Further Creation of Wound-Healing Agents. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazhenov, S.V.; Novoyatlova, U.S.; Scheglova, E.S.; Prazdnova, E.V.; Mazanko, M.S.; Kessenikh, A.G.; Kononchuk, O.V.; Gnuchikh, E.Y.; Liu, Y.; Al Ebrahim, R.; et al. Bacterial lux-biosensors: Constructing, applications, and prospects. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 13, 100323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, Q.; Lawson, T.; Shan, S.; Yan, L.; Liu, Y. The Application of Whole Cell-Based Biosensors for Use in Environmental Analysis and in Medical Diagnostics. Sensors 2017, 17, 1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilov, V.; Zarubina, A.; Eroshnikov, G.E. Sensory Bioluminescent Systems Based on the lux Operons of Different Species of Luminescent Bacteria. Vestn. Mosk. Univ. 2002, 16, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Abilev, S.K.; Igonina, E.V.; Sviridova, D.A.; Smirnova, S.V. Bacterial Lux Biosensors in Genotoxicological Studies. Biosensors 2023, 13, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotova, V.Y.; Manukhov, I.V.; Zavilgelskii, G.B. Lux-biosensors for detection of SOS-response, heat shock, and oxidative stress. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2010, 46, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavilgelsky, G.B.; Kotova, V.Y.; Manukhov, I.V. Titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles induce bacterial stress response detectable by specific lux biosensors. Nanotechnologies Russ. 2011, 6, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimova, D.N.; Manukhov, I.V.; Gnuchikh, E.Y.; Karimov, I.F.; Deryabin, D.G. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species’ effect on lux-biosensors based on Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2016, 52, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimov, I.F.; Kondrashova, K.S.; Kulikova, N.A.; Manukhov, I.V. Effects of Antioxidant Molecules on Sensor and Reporter Luminescent Strains. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2019, 55, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erental, A.; Sharon, I.; Engelberg-Kulka, H. Two programmed cell death systems in Escherichia coli: An apoptotic-like death is inhibited by the mazEF-mediated death pathway. PLoS Biol. 2012, 10, e1001281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abilev, S.K.; Kotova, V.Y.; Smirnova, S.; Shapiro, T.; Zavilgelsky, G. Specific lux biosensors of Escherichia coli containing pRecA:: Lux, pColD:: Lux, and pDinI:: Lux plasmids for detection of genotoxic agents. Russ. J. Genet. 2020, 56, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazykin, I.S.; Sazykina, M.A.; Khmelevtsova, L.E.; Mirina, E.A.; Kudeevskaya, E.M.; Rogulin, E.A. Biosensor-based comparison of the ecotoxicological contamination of the wastewaters of Southern Russia and Southern Germany. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 13, 945–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chistyakov, V.A.; Semenyuk, Y.P.; Morozov, P.G.; Prazdnova, E.V.; Chmykhalo, V.K.; Kharchenko, E.Y.; Kletskii, M.E.; Borodkin, G.S.; Lisovin, A.V.; Burov, O.N.; et al. Synthesis and biological properties of nitrobenzoxadiazole derivatives as potential nitrogen(ii) oxide donors: SOX induction, toxicity, genotoxicity, and DNA protective activity in experiments using Escherichia coli-based lux biosensors. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2015, 64, 1369–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikov, M.P.; Statsenko, V.N.; Prazdnova, E.V.; Emelyantsev, S.A. Antioxidant, DNA-protective, and SOS inhibitory activities of Enterococcus durans metabolites. Gene Rep. 2022, 27, 101544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silina, E.; Stupin, V.; Koreyba, K.; Bolevich, S.; Suzdaltseva, Y.; Manturova, N. Local and Remote Effects of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Administration on Skin Wound Regeneration. Pathophysiology 2021, 28, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silina, E.V.; Stupin, V.A.; Suzdaltseva, Y.G.; Aliev, S.R.; Abramov, I.S.; Khokhlov, N.V. Application of Polymer Drugs with Cerium Dioxide Nanomolecules and Mesenchymal Stem Cells for the Treatment of Skin Wounds in Aged Rats. Polymers 2021, 13, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silina, E.V.; Stupin, V.A.; Manturova, N.; Vasin, V.; Koreyba, K.; Litvitskiy, P.; Saltykov, A.; Balkizov, Z. Acute Skin Wounds Treated with Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Biopolymer Compositions Alone and in Combination: Evaluation of Agent Efficacy and Analysis of Healing Mechanisms. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NSW Department of Primary Industries and Animal Research Review Panel. Three Rs. Available online: https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/dpi/animals/animal-ethics-infolink/three-rs (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Pedre, B. A guide to genetically-encoded redox biosensors: State of the art and opportunities. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2024, 758, 110067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, G.A.; Erdoğan, Y.C.; Caglar, T.A.; Eroglu, E. Chemogenetic approaches to dissect the role of H2O2 in redox-dependent pathways using genetically encoded biosensors. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2022, 50, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Xie, Z.; Jiang, X.; Li, Z.; Shen, Y.; Wang, B.; Liu, J. The Applications of Promoter-gene-Engineered Biosensors. Sensors 2018, 18, 2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinna, A.; Torki Baghbaderani, M.; Vigil Hernández, V.; Naruphontjirakul, P.; Li, S.; McFarlane, T.; Hachim, D.; Stevens, M.M.; Porter, A.E.; Jones, J.R. Nanoceria provides antioxidant and osteogenic properties to mesoporous silica nanoparticles for osteoporosis treatment. Acta Biomater. 2021, 122, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Peng, E.; Ba, X.; Wu, J.; Deng, W.; Huang, Q.; Tong, Y.; Shang, H.; Zhong, Z.; Liu, X.; et al. ROS Responsive Cerium Oxide Biomimetic Nanoparticles Alleviates Calcium Oxalate Crystals Induced Kidney Injury via Suppressing Oxidative Stress and M1 Macrophage Polarization. Small 2025, 21, e2405417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.L.; Jin, G.Z. Exploring the Antioxidant Mechanisms of Nanoceria in Protecting HT22 Cells from Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, N.; Negi, D.; Singh, Y. Thiol-Functionalized, Antioxidant, and Osteogenic Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for Osteoporosis. ACS Biomater Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 3535–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; He, Q.; Zhai, Q.; Tang, H.; Li, D.; Zhu, X.; Zheng, X.; Jian, G.; Cannon, R.D.; Mei, L.; et al. Adaptive Nanoparticle-Mediated Modulation of Mitochondrial Homeostasis and Inflammation to Enhance Infected Bone Defect Healing. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 22960–22978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, V.; Pandey, A. Synthesis and characterization of CeO2 and SiO2 nanoparticles and their effect on growth parameters and the antioxidant defense system in Vigna mungo L. Hepper. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 100814–100827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, M.; Gowtham, H.G.; Shilpa, N.; Singh, S.B.; Aiyaz, M.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Shivamallu, C.; Achar, R.R.; Silina, E.; Stupin, V.; et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles prepared through microbial mediated synthesis for therapeutic applications: A possible alternative for plants. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1227951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbasz, A.; Oćwieja, M.; Piergies, N.; Duraczyńska, D.; Nowak, A. Antioxidant-modulated cytotoxicity of silver nanoparticles. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2021, 41, 1863–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, T.; Afsheen, S.; Iqbal, T. Nanocidal Effect of Rice Husk-Based Silver Nanoparticles on Antioxidant Enzymes of Aphid. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2022, 200, 4855–4864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, N.; Liu, Y.; Dai, X.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Q.; Li, Q. Advanced applications of cerium oxide based nanozymes in cancer. RSC Advances 2022, 12, 1486–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Cheng, N.; Zhang, J.; Huang, H.; Yuan, Y.; He, X.; Luo, Y.; Huang, K. Nanoscale Cerium Oxide: Synthesis, Biocatalytic Mechanism, and Applications. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, M.; Barayeu, U.; Gharibi, H.; Kuzhelev, A.; Riedmiller, K.; Zilke, J.; Noack, K.; Denysenkov, V.; Kappl, R.; Prisner, T.F.; et al. DOPA Residues Endow Collagen with Radical Scavenging Capacity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202216610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soeiro, V.C.; Melo, K.R.; Alves, M.G.; Medeiros, M.J.; Grilo, M.L.; Almeida-Lima, J.; Pontes, D.L.; Costa, L.S.; Rocha, H.A. Dextran: Influence of Molecular Weight in Antioxidant Properties and Immunomodulatory Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Luo, D.; Liang, M.; Zhang, T.; Yin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, W. Spectrum-Effect Relationships between High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) Fingerprints and the Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Collagen Peptides. Molecules 2018, 23, 3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupu, A.; Gradinaru, L.M.; Balan-Porcarasu, M.; Darie-Ion, L.; Petre, B.A.; Gradinaru, V.R. The hidden power of a novel collagen octapeptide: Unveiling its antioxidant and cofactors releasing capacity from polyurethane based systems. React. Funct. Polym. 2025, 207, 106131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naha, P.C.; Hsu, J.C.; Kim, J.; Shah, S.; Bouché, M.; Si-Mohamed, S.; Rosario-Berrios, D.N.; Douek, P.; Hajfathalian, M.; Yasini, P.; et al. Dextran-Coated Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles: A Computed Tomography Contrast Agent for Imaging the Gastrointestinal Tract and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 10187–10197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.; Šmíd, B.; Johánek, V.; Khalakhan, I.; Yakovlev, Y.; Matolínová, I.; Matolín, V. Investigation of dextran adsorption on polycrystalline cerium oxide surfaces. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 544, 148890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konduru, N.V.; Jimenez, R.J.; Swami, A.; Friend, S.; Castranova, V.; Demokritou, P.; Brain, J.D.; Molina, R.M. Silica coating influences the corona and biokinetics of cerium oxide nanoparticles. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2015, 12, 31, Erratum in Part Fibre Toxicol. 2016, 13, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.; Gong, L.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liao, F. Cerium Oxide-Loaded Exosomes Derived From Regulatory T Cells Ameliorate Inflammatory Bowel Disease by Scavenging Reactive Oxygen Species and Modulating the Inflammatory Response. J. Inflamm. Res. 2025, 18, 4395–4408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, F.; Huang, F.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, P.; Wei, H. Nanoceria as an Electron Reservoir: Spontaneous Deposition of Metal Nanoparticles on Oxides and Their Anti-inflammatory Activities. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 20567–20576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-da-Silva, N.C.; Correa, L.B.; Gonzalez, M.M.; Franca, A.R.S.; Alencar, L.M.R.; Rosas, E.C.; Ricci-Junior, E.; Aguiar, T.K.B.; Souza, P.F.N.; Santos-Oliveira, R. Nanoceria Anti-inflammatory and Antimicrobial Nanodrug: Cellular and Molecular Mechanism of Action. Curr. Med. Chem. 2025, 32, 1017–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.S.; Hadrick, K.; Chung, S.J.; Carley, I.; Yoo, J.Y.; Nahar, S.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, T.; Jeong, J.W. Nanoceria as a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug for endometriosis theranostics. J. Control Release 2025, 378, 1015–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San Miguel, S.M.; Opperman, L.A.; Allen, E.P.; Zielinski, J.; Svoboda, K.K. Bioactive polyphenol antioxidants protect oral fibroblasts from ROS-inducing agents. Arch. Oral Biol. 2012, 57, 1657–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.S.; Park, B.S.; Kim, H.K.; Park, J.S.; Kim, K.J.; Choi, J.S.; Chung, S.J.; Kim, D.D.; Sung, J.H. Evidence supporting antioxidant action of adipose-derived stem cells: Protection of human dermal fibroblasts from oxidative stress. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2008, 49, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muire, P.J.; Thompson, M.A.; Christy, R.J.; Natesan, S. Advances in Immunomodulation and Immune Engineering Approaches to Improve Healing of Extremity Wounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CeO2 and Collagen Content in the Final Concentration of the Prototype Drug | Nanoparticles (CeO-CA, CeO-Dex) | Collagen-Containing Extract, mL | Phosphate Buffer (mL) | Total Volume (mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CeO2 (10−3 M) + Collagen (10%) | 10−2 M—10 mL | 10 | 80 | 100 |

| CeO2 (10−3 M) + Collagen (1%) | 10−2 M—10 mL | 1 | 89 | 100 |

| CeO2 (10−4 M) + Collagen (10%) | 10−3 M—10 mL | 10 | 80 | 100 |

| CeO2 (10−4 M) + Collagen (1%) | 10−3 M—10 mL | 1 | 89 | 100 |

| No | Collagen | CeO-CA NPs | CeO-Dex NPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10% | 10−3 M | – |

| 2 | 10% | 10−4 M | – |

| 3 | 10% | – | 10−3 M |

| 4 | 10% | – | 10−4 M |

| 5 | 1% | 10−3 M | – |

| 6 | 1% | 10−4 M | – |

| 7 | 1% | – | 10−3 M |

| 8 | 1% | – | 10−4 M |

| E. coli Strains | Detectable Change Type | Measurable Factor |

|---|---|---|

| MG1655 pXen7 | Decrease | Toxicity |

| MG1655 pKatG | Increase/Decrease | Prooxidant/antioxidant activity (hydrogen peroxide) |

| MG1655 pSoxS | Increase/Decrease | Prooxidant/antioxidant activity (superoxide anion radical) |

| MG1655 pRecA | Increase/Decrease | Antigenotoxic/promutagenic activity |

| Control (C) | CeO-CA + Collagen + (1) | CeO-Dex + Collagen (2) | Dexapantenol (D) | p-Value (Total) | p-Value with the Bonferroni Correction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | 144,7 [128.3, 170.3] | 143,1 [121.9, 158.1] | 141,9 [116.1, 161.7] | 149,2 [137.2, 173.0] | 0.328 | |

| Day 3 | 125.9 [120.2, 146.0] | 121.8 [97.9, 133.8] | 117.1 [89.7, 123.0] | 135.4 [121.4, 155.0] | 0.003 C/2 * D/2 * D/1 * | D/2 (0.003) |

| Day 7 | 81.2 [70.6, 95.5] | 68.4 [47.4, 78.9] | 59.1 [41.2, 87.7] | 62.2 [47.2, 79.6] | 0.041 C/1 * C/2 * C/D * | K/2 (0.042) |

| Day 14 | 13.5 [9.06, 15.9] | 6.5 [4.5, 8.3] | 9.3 [6.9, 13.9] | 13.2 [8.8, 19.9] | 0.004 C/1 * D/1 * | K/1 (0.022) D/1 (0.006) |

| Day | Number of Cells in the | Control (C) | CeO-CA + Collagen + (1) | CeO-Dex + Collagen (2) | Dexapantenol (D) | p-Value (Total) | p-Value with the Bonferroni Correction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Leukocytes | 44 [26, 56] | 29 [22, 51] | 30 [24, 44] | 26 [20, 32] | 0.067 | |

| 3 | Fibroblasts | 63 [46, 78] | 49 [39, 71] | 48 [35, 82] | 56 [36, 71] | 0.314 | |

| 7 | Leukocytes | 33 [24, 46] | 32 [18, 45] | 23 [14, 26] | 32 [19, 44] | 0.008 * | C/2, 2/D |

| 7 | Fibrocytes | 13 [8, 29] | 10 [6, 15] | 17 [9, 18] | 12 [3, 17] | 0.745 | |

| 7 | Fibroblasts | 23 [11, 56] | 35 [22, 54] | 22 [13, 31] | 27 [23, 40] | 0.036 * | 1/2 |

| 14 | Leukocytes | 69 [64, 75] | 42 [27, 64] | 30 [24, 41] | 51 [41, 73] | 0.029 * | C/2 |

| 14 | Fibrocytes | 32 [20, 35] | 79 [61, 88] | 63 [57, 91] | 36 [33, 52] | 0.005 * | C/1, C/2 |

| 14 | Fibroblasts | 70 [63, 76] | 91 [83, 97] | 77 [57, 85] | 56 [38, 89] | 0.049 * | 1/D |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silina, E.V.; Manturova, N.E.; Sevastianov, V.I.; Perova, N.V.; Gladchenko, M.P.; Kryukov, A.A.; Ivanov, A.V.; Dudka, V.T.; Prazdnova, E.V.; Emelyantsev, S.A.; et al. Development of a Collagen–Cerium Oxide Nanohydrogel for Wound Healing: In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2623. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112623

Silina EV, Manturova NE, Sevastianov VI, Perova NV, Gladchenko MP, Kryukov AA, Ivanov AV, Dudka VT, Prazdnova EV, Emelyantsev SA, et al. Development of a Collagen–Cerium Oxide Nanohydrogel for Wound Healing: In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(11):2623. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112623

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilina, Ekaterina Vladimirovna, Natalia Evgenievna Manturova, Victor Ivanovich Sevastianov, Nadezhda Victorovna Perova, Mikhail Petrovich Gladchenko, Alexey Anatolievich Kryukov, Aleksandr Victorovich Ivanov, Victor Tarasovich Dudka, Evgeniya Valerievna Prazdnova, Sergey Alexandrovich Emelyantsev, and et al. 2025. "Development of a Collagen–Cerium Oxide Nanohydrogel for Wound Healing: In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation" Biomedicines 13, no. 11: 2623. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112623

APA StyleSilina, E. V., Manturova, N. E., Sevastianov, V. I., Perova, N. V., Gladchenko, M. P., Kryukov, A. A., Ivanov, A. V., Dudka, V. T., Prazdnova, E. V., Emelyantsev, S. A., Kozhukhova, E. I., Parfenov, V. A., Ivanov, A. V., Popov, M. A., & Stupin, V. A. (2025). Development of a Collagen–Cerium Oxide Nanohydrogel for Wound Healing: In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation. Biomedicines, 13(11), 2623. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112623