The Role of GLP-1 Analogues in the Treatment of Obesity-Related Asthma Phenotype

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Asthma Phenotypes and Endotypes

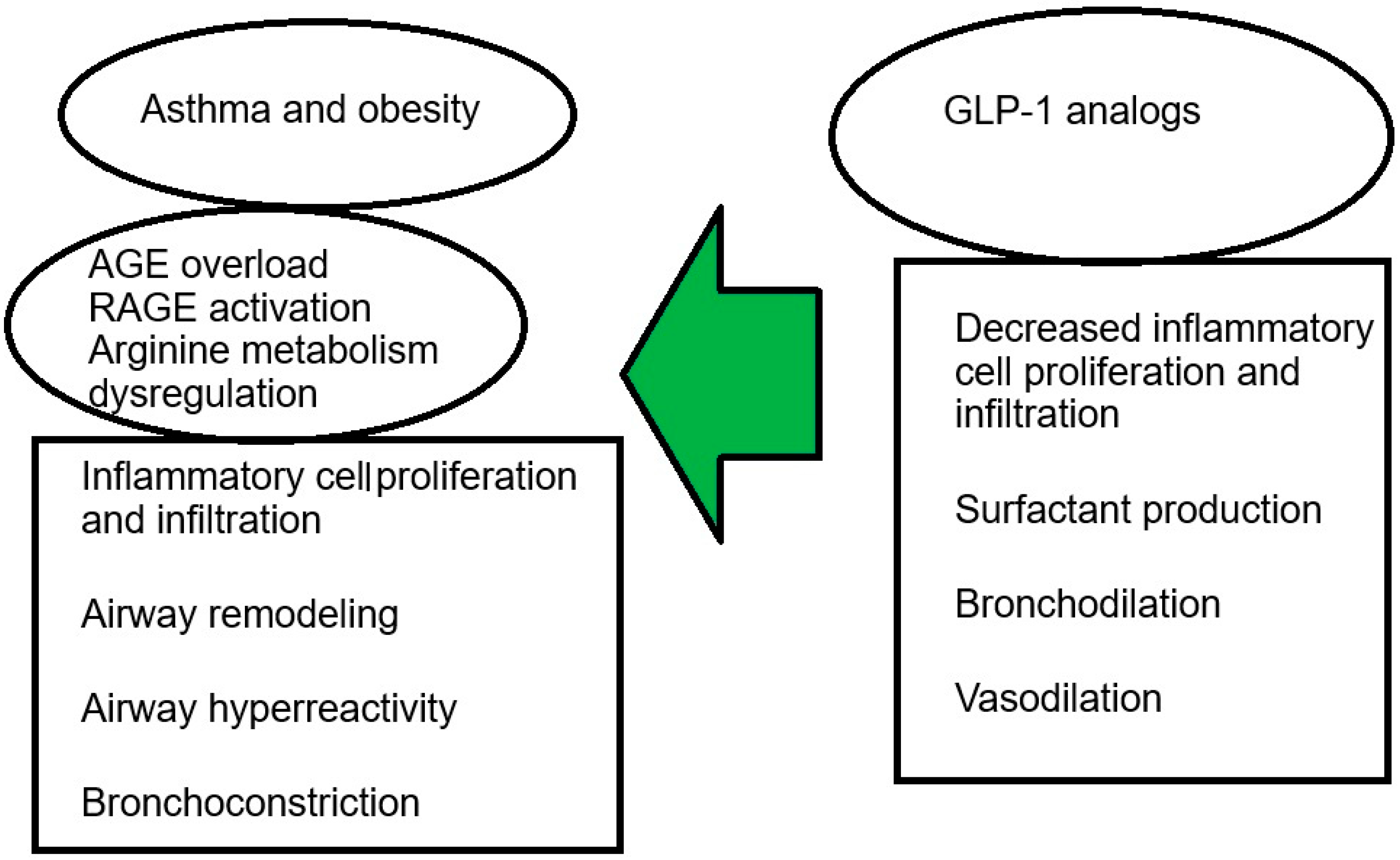

4. The Impact of Obesity on Asthma

5. The Role of GLP-1 Receptor Analogues in the Treatment of Asthma in Obese Individuals

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACQ | Asthma Control Questionnaire |

| ACT | Asthma Control Test |

| AGE | advanced glycation end products |

| AQLQ | Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| FeNO | Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide |

| GIP | glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide |

| GLP-1 | glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| GLP-1 | analogues to asthma treatment in obese individuals |

| IgE | Immunoglobulin E |

| MASLD | metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease |

| mini AQLQ | mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| PEF | peak expiratory flow |

| RAGE | advanced glycation end products receptor |

| RCTs | randomised controlled trails |

| T2DM | type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| Th | helper lymphocytes |

References

- WHO. Asthma—Key Facts. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/asthma (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. 2025. Available online: www.ginasthma.org (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Kaur, R.; Chupp, G. Phenotypes and endotypes of adult asthma: Moving toward precision medicine. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 144, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, W.C.; Meyers, D.A.; Wenzel, S.E.; Teague, W.G.; Li, H.; Li, X.; D’Agostino, R.; Castro, M.; Curran-Everett, D.; Fitzpatrick, A.M.; et al. Identification of Asthma Phenotypes Using Cluster Analysis in the Severe Asthma Research Program. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 181, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, S.E. Asthma: Defining of the persistent adult phenotypes. Lancet 2006, 368, 804–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel, E.H. Clinical phenotypes of asthma. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2004, 10, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lötvall, J.; Akdis, C.A.; Bacharier, L.B.; Bjermer, L.; Casale, T.B.; Custovic, A.; Lemanske, R.F.L.; Wardlaw, A.J.; Wenzel, S.E.; Greenberger, P.A. Asthma endotypes: A new approach to classification of disease entities within the asthma syndrome. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 127, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutel, M.; Agache, I.; Zemelka-Wiacek, M.; Akdis, M.; Chivato, T.; del Giacco, S.; Gajdanowicz, P.; Gracia, I.E.; Klimek, L.; Lauerma, A.; et al. Nomenclature of allergic diseases and hypersensitivity reactions: Adapted to modern needs: An EAACI position paper. Allergy 2023, 78, 2851–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Obesity and Overweight. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- World Obesity Atlas 2025 n.d. Available online: https://data.worldobesity.org/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Forno, E.; Lescher, R.; Strunk, R.; Weiss, S.; Fuhlbrigge, A.; Celedón, J.C. Decreased response to inhaled steroids in overweight and obese asthmatic children. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 127, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forno, E.; Han, Y.-Y.; Mullen, J.; Celedón, J.C. Overweight, Obesity, and Lung Function in Children and Adults—A Meta-analysis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018, 6, 570–581.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, A.E.; Peters, U. The effect of obesity on lung function. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2018, 12, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mraz, M.; Haluzik, M. The role of adipose tissue immune cells in obesity and low-grade inflammation. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 222, R113–R127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.Y.; Cahill, K.N.; Toki, S.; Peebles, R.S. Evaluating the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor in managing asthma. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 22, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainardi, V.; Esposito, S.; Chetta, A.; Pisi, G. Asthma phenotypes and endotypes in childhood. Minerva Medica 2022, 113, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuruvilla, M.E.; Lee, F.E.-H.; Lee, G.B. Understanding Asthma Phenotypes, Endotypes, and Mechanisms of Disease. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2019, 56, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsthoorn, S.E.M.; van Krimpen, A.; Hendriks, R.W.; Stadhouders, R. Chronic Inflammation in Asthma: Looking Beyond the Th2 Cell. Immunol. Rev. 2025, 330, e70010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammad, H.; Lambrecht, B.N. The basic immunology of asthma. Cell 2021, 184, 1469–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahy, J.V. Type 2 inflammation in asthma—Present in most, absent in many. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelaia, G.; Vatrella, A.; Busceti, M.T.; Gallelli, L.; Calabrese, C.; Terracciano, R.; Maselli, R. Cellular Mechanisms Underlying Eosinophilic and Neutrophilic Airway Inflammation in Asthma. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 879783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, T.; Li, H. T-helper cells and their cytokines in pathogenesis and treatment of asthma. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1149203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinks, T.S.C.; Levine, S.J.; Brusselle, G.G. Treatment options in type-2 low asthma. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 57, 2000528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, U.; Dixon, A.E.; Forno, E. Obesity and asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 141, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stream, A.R.; Sutherland, E.R. Obesity and asthma disease phenotypes. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 12, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cildir, G.; Akıncılar, S.C.; Tergaonkar, V. Chronic adipose tissue inflammation: All immune cells on the stage. Trends Mol. Med. 2013, 19, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, E.B. The complex role of adipokines in obesity, inflammation, and autoimmunity. Clin. Sci. 2021, 135, 731–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantulà, M.; Roca-Ferrer, J.; Arismendi, E.; Picado, C. Asthma and Obesity: Two Diseases on the Rise and Bridged by Inflammation. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Kusminski, C.M.; Scherer, P.E. Adipose tissue remodeling and obesity. J. Clin. Invest. 2011, 121, 2094–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caslin, H.L.; Bhanot, M.; Bolus, W.R.; Hasty, A.H. Adipose tissue macrophages: Unique polarization and bioenergetics in obesity. Immunol. Rev. 2020, 295, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Yang, H. Modulation of macrophage activation and programming in immunity. J. Cell Physiol. 2013, 228, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.-V.; Linderholm, A.; Haczku, A.; Kenyon, N. Glucagon-like peptide 1: A potential anti-inflammatory pathway in obesity-related asthma. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 180, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, S.; Nakamura, N.; Suematsu, M.; Kaseda, K.; Matsui, T. Advanced Glycation End Products: A Molecular Target for Vascular Complications in Diabetes. Mol. Med. 2015, 21, S32–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Strub, P.; Xiao, L.; Lavori, P.W.; Camargo, C.A.; Wilson, S.R.; Gardner, C.D.; Buist, A.S.; Haskell, W.L.; Lv, N. Behavioral Weight Loss and Physical Activity Intervention in Obese Adults with Asthma. A Randomized Trial. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2015, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pakhale, S.; Baron, J.; Dent, R.; Vandemheen, K.; Aaron, S.D. Effects of Weight Loss on Airway Responsiveness in Obese Adults with Asthma. Chest 2015, 147, 1582–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, P.D.; Ferreira, P.G.; Silva, A.G.; Stelmach, R.; Carvalho-Pinto, R.M.; Fernandes, F.L.A.; Mancini, M.C.; Sato, M.N.; Martins, M.A.; Carvalho, C.R.F. The Role of Exercise in a Weight-Loss Program on Clinical Control in Obese Adults with Asthma. A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 195, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Tian, Y.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, J. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: Mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, N.; Hölscher, C. The neuroprotective effects of glucagon-like peptide 1 in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease: An in-depth review. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 970925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meurot, C.; Jacques, C.; Martin, C.; Sudre, L.; Breton, J.; Rattenbach, R.; Bismuth, K.; Berenbaum, F. Targeting the GLP-1/GLP-1R axis to treat osteoarthritis: A new opportunity? J. Orthop. Transl. 2022, 32, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badve, S.V.; Bilal, A.; Lee, M.M.Y.; Sattar, N.; Gerstein, H.C.; Ruff, C.T.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Rossing, P.; Bakris, G.; Mahaffey, K.W.; et al. Effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists on kidney and cardiovascular disease outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligumsky, H.; Wolf, I.; Israeli, S.; Haimsohn, M.; Ferber, S.; Karasik, A.; Kaufman, B.; Rubinek, T. The peptide-hormone glucagon-like peptide-1 activates cAMP and inhibits growth of breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012, 132, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Wang, X.; Ren, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yang, M.; Li, J. High glucose promotes the progression of colorectal cancer by activating the BMP4 signaling and inhibited by glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.K. Mechanisms of action and therapeutic applications of GLP-1 and dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1431292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, S.F.; Pusapati, S.; Anwar, M.S.; Lohana, D.; Kumar, P.; Nandula, S.A.; Nawaz, F.K.; Tracey, K.; Yang, H.; LeRoith, D.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1: A multi-faceted anti-inflammatory agent. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1148209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Wu, X.; Zhang, W.; Xiao, M. Glucagon Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) Modulates OVA-Induced Airway Inflammation and Mucus Secretion Involving a Protein Kinase A (PKA)-Dependent Nuclear Factor-κB (NF-κB) Signaling Pathway in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 20195–20211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Shimizu, T.; Fujita, H.; Imai, Y.; Drucker, D.J.; Seino, Y.; Yamada, Y. GLP-1 Receptor Signaling Differentially Modifies the Outcomes of Sterile vs Viral Pulmonary Inflammation in Male Mice. Endocrinology 2020, 161, bqaa201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toki, S.; Newcomb, D.C.; Printz, R.L.; Cahill, K.N.; Boyd, K.L.; Niswender, K.D.; Peebles, R.S. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist inhibits aeroallergen-induced activation of ILC2 and neutrophilic airway inflammation in obese mice. Allergy 2021, 76, 3433–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, S.; Zhu, T.; Wang, W.; Xiao, M.; Wang, X.-C.; Chen, Z.-H. Glucagon like peptide-1 attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, involving the inactivation of NF-κB in mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2014, 22, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogliani, P.; Calzetta, L.; Capuani, B.; Facciolo, F.; Cazzola, M.; Lauro, D.; Matera, M.G. Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor: A Novel Pharmacological Target for Treating Human Bronchial Hyperresponsiveness. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2016, 55, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Mat, A.; E Hogan, A.; Kent, B.D.; Eigenheer, S.; Corrigan, M.; O’Shea, D.; Butler, M.W. Preliminary asthma-related outcomes following glucagon-like peptide 1 agonist therapy. QJM Int. J. Med. 2017, 110, 853–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albogami, Y.; Cusi, K.; Daniels, M.J.; Wei, Y.-J.J.; Winterstein, A.G. Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonists and Chronic Lower Respiratory Disease Exacerbations Among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 1344–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foer, D.; Beeler, P.E.; Cui, J.; Karlson, E.W.; Bates, D.W.; Cahill, K.N. Asthma Exacerbations in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Asthma on Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 203, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foer, D.; Beeler, P.; Cui, J.; Boyce, J.; Karlson, E.; Bates, D.; Cahill, K. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists decrease systemic Th2 inflammation in asthmatics. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, AB241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billington, C.K.; Ojo, O.O.; Penn, R.B.; Ito, S. cAMP regulation of airway smooth muscle function. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 26, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, P.D.; Salter, B.M.; Oliveria, J.P.; El-Gammal, A.; Tworek, D.; Smith, S.G.; Sehmi, R.; Gauvreau, G.M.; Butler, M.; O’Byrne, P.M. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor expression on human eosinophils and its regulation of eosinophil activation. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2017, 47, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogliani, P.; Matera, M.G.; Calzetta, L.; Hanania, N.A.; Page, C.; Rossi, I.; Andreadi, A.; Galli, A.; Coppola, A.; Cazzola, M.; et al. Long-term observational study on the impact of GLP-1R agonists on lung function in diabetic patients. Respir. Med. 2019, 154, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Keil, A.P.; Buse, J.B.; Keet, C.; Kim, S.; Wyss, R.; Pate, V.; Jonsson-Funk, M.; Pratley, R.E.; Kvist, K.; et al. Glucagon-like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonists and Asthma Exacerbations: Which Patients Benefit Most? Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2024, 21, 1496–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.; Heatley, H.; Townend, J.; Skinner, D.; Carter, V.; Hubbard, R.; Lee, T.; Koh, M.S.; Price, D. CO59 Do Asthma Patients Prescribed a GLP1 Have Improved Asthma and Weight Loss Outcomes? Value Health 2024, 27, S25–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.P.; Aggarwal, R.; Singh, S.; Banik, A.; Ahmad, T.; Patnaik, B.R.; Nappanveettil, G.; Singh, K.P.; Aggarwal, M.L.; Ghosh, B.; et al. Metabolic Syndrome Is Associated with Increased Oxo-Nitrative Stress and Asthma-Like Changes in Lungs. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, J.; Kang, J.Y.; Kim, Y.K.; Lee, S.Y.; Lee, H.Y. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonist relieved asthmatic airway inflammation via suppression of NLRP3 inflammasome activation in obese asthma mice model. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 67, 102003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toki, S.; Goleniewska, K.; Reiss, S.; Zhang, J.; Bloodworth, M.H.; Stier, M.T.; Zhou, W.; Newcomb, D.C.; Ware, L.B.; Stanwood, G.D.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 signaling inhibits allergen-induced lung IL-33 release and reduces group 2 innate lymphoid cell cytokine production in vivo. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 142, 1515–1528.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Tan, J.; Yuan, Y.; Shen, J.; Chen, Y. Semaglutide ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury through inhibiting HDAC5-mediated activation of NF-κB signaling pathway. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2022, 41, 9603271221125931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toki, S.; Zhang, J.; Printz, R.L.; Newcomb, D.C.; Cahill, K.N.; Niswender, K.D.; Peebles, R.S. Dual GIPR and GLP-1R agonist tirzepatide inhibits aeroallergen-induced allergic airway inflammation in mouse model of obese asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2023, 53, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figat, M.; Kardas, G.; Kuna, P.; Panek, M.G. Beneficial Influence of Exendin-4 on Specific Organs and Mechanisms Favourable for the Elderly with Concomitant Obstructive Lung Diseases. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Asthma Th2-High | Asthma Th2-Low |

|---|---|

| Children and adults | Adults (female predominance) |

| Eosinophilic inflammation | Neutrophilic inflammation |

| Th2 inflammatory cytokines: IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 | Th1 inflammatory cytokines: IL-8, IL-17 |

| Responsiveness to glucocorticosteroids | Lack of responsiveness to glucocorticosteroids |

| Responsiveness to inhibitors of type 2 inflammation | Lack of responsiveness to inhibitors of type 2 inflammation |

| GLP-1 Analogues | In Vivo/Ex Vivo Animal Studies | Human Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Lixisenatide | No data available | No data available |

| Exenatide /exendin-4 | Isolated human bronchi—dilation [49] | No data available |

| Liraglutide | Inhibition of eosinophilic bronchitis and bronchial hyperresponsiveness in mice [60] Inhibition of IL-33, IL-5, IL-13 release, reduction in pulmonary eosinophilia [61] Reduction in pulmonary fibrosis [48] Reduction in inflammation and mucus secretion in OVA-induced asthma [45] | No data available |

| Semaglutide | Reduces acute lung injury [62] | No data available |

| GIP/GLP-1R agonist | ||

| Tirzepatide | Reduction in leptin concentration, anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic effects in asthma in mice [63] | No data available |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Radzik-Zając, J. The Role of GLP-1 Analogues in the Treatment of Obesity-Related Asthma Phenotype. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2610. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112610

Radzik-Zając J. The Role of GLP-1 Analogues in the Treatment of Obesity-Related Asthma Phenotype. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(11):2610. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112610

Chicago/Turabian StyleRadzik-Zając, Joanna. 2025. "The Role of GLP-1 Analogues in the Treatment of Obesity-Related Asthma Phenotype" Biomedicines 13, no. 11: 2610. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112610

APA StyleRadzik-Zając, J. (2025). The Role of GLP-1 Analogues in the Treatment of Obesity-Related Asthma Phenotype. Biomedicines, 13(11), 2610. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112610