A Retrospective Study Regarding the Implementation of Laparoscopy in Colon Cancer Through the Evaluation of Lymph Node Yield and Oncological Safety Margins in a Medium-Volume Center in Eastern Europe

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Adjustment for Confounding and Bias

3. Results

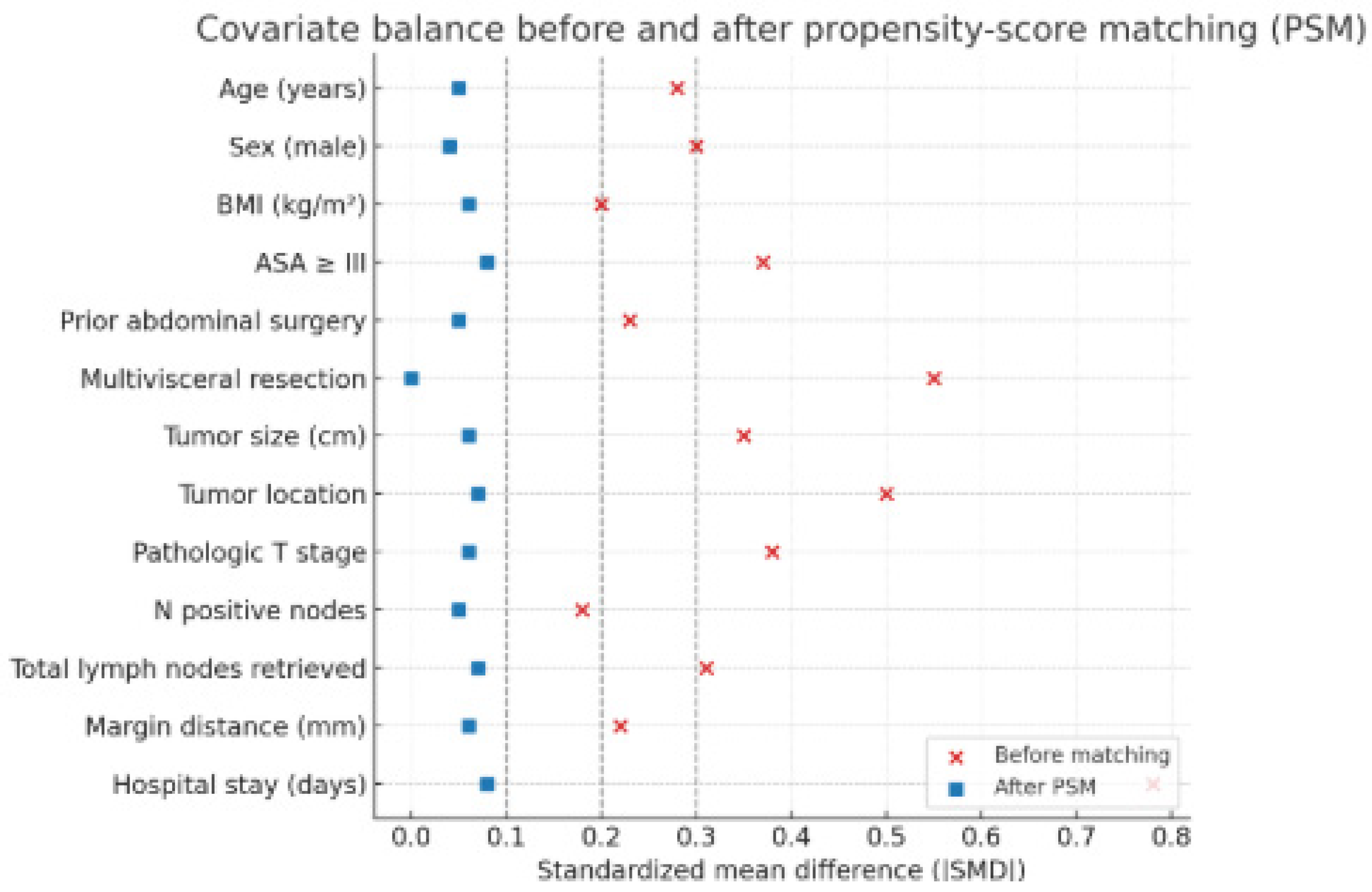

Adjustment for Confounding and Bias

4. Discussion

- (1)

- Progressive case selection for early-stage, technically favorable tumors, which in our series were significantly more likely to undergo LS (χ2(5) = 16.72, p < 0.01);

- (2)

- (3)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LS | Laparoscopy |

| CRM | Circumferential resection margin |

| OS | Open surgery |

| BMI | Body mass index |

References

- Jacobs, M.; Verdeja, J.C.; Goldstein, H.S. Minimally invasive colon resection (laparoscopic colectomy). Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. 1991, 1, 144–150. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhry, E.; Schwenk, W.; Gaupset, R.; Romild, U.; Bonjer, H.J.; Cochrane Colorectal Cancer Group. Long-term results of laparoscopic colorectal cancer resection. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, 2008, CD003432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, A.M.; García-Valdecasas, J.C.; Delgado, S.; Castells, A.; Taule, J.; Piqué, J.M. Laparoscopy-assisted colectomy versus open colectomy for non-metastatic colon cancer: A randomised trial. Lancet 2002, 359, 2224–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theophilus, M.; Platell, C.; Spilsbury, K.; Phillips, D. Long-term survival following laparoscopic and open colectomy for colon cancer: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Color. Dis. 2014, 16, O75–O81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devoto, L.; Celentano, V.; Cohen, R.; Khan, J.; Chand, M. Colorectal cancer surgery in the very elderly patient: A systematic review of laparoscopic versus open colorectal resection. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2017, 32, 1237–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, P.R.; Joseph, A.; Haray, P.N. Laparoscopic colorectal surgery: Learning curve and training implications. Postgrad. Med. J. 2005, 81, 537–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekkis, P.P.; Senagore, A.J.; Delaney, C.P.; Fazio, V.W. Evaluation of the learning curve in laparoscopic colorectal surgery: Comparison of right-sided and left-sided resections. Ann. Surg. 2005, 242, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonjer, H.J.; Deijen, C.L.; Abis, G.A.; Cuesta, M.A.; van der Pas, M.H.; de Lange-de Klerk, E.S.; Lacy, A.M.; Bemelman, W.A.; Andersson, J.; Angenete, E.; et al. A randomized trial of laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1324–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gietelink, L.; Wouters, M.W.; Bemelman, W.A.; Dekker, J.W.; Tollenaar, R.A.; Tanis, P.J.; Dutch Surgical Colorectal Cancer Audit Group. Reduced 30-Day Mortality After Laparoscopic Colorectal Cancer Surgery: A Population-Based Study From the Dutch Surgical Colorectal Audit (DSCA). Ann. Surg. 2016, 264, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warps, A.K.; Saraste, D.; Westerterp, M.; Detering, R.; Sjövall, A.; Martling, A.; Dekker, J.W.T.; Tollenaar, R.A.E.M.; Matthiessen, P.; Tanis, P.J.; et al. National differences in implementation of minimally invasive surgery for colorectal cancer and the influence on short-term outcomes. Surg. Endosc. 2022, 36, 5986–6001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, A.J.; Simpson, A.; Humes, D.J. Regional variations and deprivation are linked to poorer access to laparoscopic and robotic colorectal surgery: A national study in England. Tech. Coloproctol. 2023, 28, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, M.G.; Hanna, G.B.; Kennedy, R.; National Training Programme (Lapco). The National Training Programme for Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgery in England: A new training paradigm. Color. Dis. 2011, 13, 614–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.F.; Thomas, J.D.; Whitehouse, L.E.; Quirke, P.; Jayne, D.; Finan, P.J.; Forman, D.; Wilkinson, J.R.; Morris, E.J. Population-based study of laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery 2006–2008. Br. J. Surg. 2013, 100, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadban, T.; Reeh, M.; Bockhorn, M.; Heumann, A.; Grotelueschen, R.; Bachmann, K.; Izbicki, J.R.; Perez, D.R. Minimally invasive surgery for colorectal cancer remains underutilized in Germany despite its nationwide application over the last decade. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bintintan, V.V.; Fagarasan, V.; Seicean, R.I.; Andras, D.; Ene, A.I.; Chira, R.; Bintintan, A.; Nagy, G.; Petrisor, C.; Cocu, S.; et al. Laparoscopic Radical Colectomy with Complete Mesocolic Excision Offers Similar Results Compared with Open Surgery. Medicina 2025, 61, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Negrut, R.L.; Cote, A.; Caus, V.A.; Maghiar, A.M. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Laparoscopic versus Robotic-Assisted Surgery for Colon Cancer: Efficacy, Safety, and Outcomes-A Focus on Studies from 2020-2024. Cancers 2024, 16, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Morarasu, S.; Clancy, C.; Gorgun, E.; Yilmaz, S.; Ivanecz, A.; Kawakatsu, S.; Musina, A.M.; Velenciuc, N.; Roata, C.E.; Dimofte, G.M.; et al. Laparoscopic versus open resection of primary colorectal cancers and synchronous liver metastasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2023, 38, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S. Simplified and reproducible laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision with D3 right hemicolectomy. Color. Dis. 2025, 27, 17242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedrazzani, C.; Conti, C.; Zamboni, G.A.; Chincarini, M.; Turri, G.; Valdegamberi, A.; Guglielmi, A. Impact of visceral obesity and sarcobesity on surgical outcomes and recovery after laparoscopic resection for colorectal cancer. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 3763–3770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.C.; Lin, W.L.; Shi, H.Y.; Huang, C.C.; Chen, J.J.; Su, S.B.; Lai, C.C.; Chao, C.M.; Tsao, C.J.; Chen, S.H.; et al. Comparison of Oncologic Outcomes in Laparoscopic versus Open Surgery for Non-Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Personal Experience in a Single Institution. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edge, S.B.; Compton, C.C. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: The 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2010, 17, 1471–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szostek, J.; Serafin, M.; Mąka, M.; Jabłońska, B.; Mrowiec, S. Right- vs left-sided colon cancer: 5-year single-centre observational study. Cancers 2025, 17, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghioldis, A.C.; Sarbu, V.; Dan, C.; Butelchin, C.; Olteanu, C.; Popescu, R.C. Open versus laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer in elderly patients with comorbidities. Arch. Balk. Med. Union. 2024, 59, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.; Erkan, A.; Alhassan, N.; Kelly, J.J.; Nassif, G.J.; Albert, M.R.; Monson, J.R. Lower survival after right- vs left-sided colon cancers: Is extended lymphadenectomy the answer? Surg. Oncol. 2018, 27, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balciscueta, Z.; Balciscueta, I.; Uribe, N.; Pellino, G.; Frasson, M.; García-Granero, E.; Garcia-Granero, A. D3-lymphadenectomy enhances oncological clearance in right colon cancer: Meta-analysis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 47, 1541–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhoff, R.; Sjövall, A.; Buchli, C.; Granath, F.; Holm, T.; Martling, A. Complete mesocolic excision in right-sided colon cancer does not increase severe short-term postoperative adverse events. Color. Dis. 2018, 20, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.H.; Yang, B.; Su, X.Q.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Z. Comparison of clinical efficacy and postoperative inflammatory response between laparoscopic and open radical resection of colorectal cancer. World J. Clin. Cases 2022, 10, 4042–4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Macovei Oprescu, A.M.; Dumitriu, B.; Stefan, M.A.; Oprescu, C.; Venter, D.P.; Mircea, V.; Valcea, S. Open Versus Laparoscopic Oncological Resections for Colon Cancer: An Experience at an Average-Volume Center. Cureus 2024, 16, e70535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enciu, O.; Avino, A.; Calu, V.; Toma, E.A.; Tulin, A.; Tulin, R.; Slavu, I.; Răducu, L.; Balcangiu-Stroescu, A.E.; Gheoca Mutu, D.E.; et al. Laparoscopic vs open resection for colon cancer-quality of oncologic resection evaluation in a medium volume center. Exp. Ther. Med. 2022, 24, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Huh, J.W.; Park, Y.A.; Cho, Y.B.; Yun, S.H.; Kim, H.C.; Lee, W.Y.; Chun, H.K. Clinically suspected T4 colorectal cancer may be resected laparoscopically. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, M.; Vignali, A.; Zuliani, W.; Frasson, M.; Di Serio, C.; Di Carlo, V. Laparoscopic vs open colorectal surgery: Cost-benefit analysis in a randomized trial. Ann. Surg. 2005, 242, 890–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Johnston, S.; Goldstein, L.; Nagle, D. Minimally invasive colectomy is associated with reduced risk of anastomotic leak and other major perioperative complications and reduced hospital resource utilization as compared with open surgery: A retrospective population-based study of comparative effectiveness and trends of surgical approach. Surg. Endosc. 2020, 34, 610–621. [Google Scholar]

- American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). AJCC 8th Edition Colon and Rectal Cancer Staging: Colon & Rectal—Webinar/Presentation. 2018. Available online: https://www.facs.org/media/vf4n5vzd/colorectal-8th-ed.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Huang, F.; Jiang, S.; Wei, R.; Xiao, T.; Wei, F.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, Q. Association of resection margin distance with anastomotic recurrence in stage I-III colon cancer: Data from the National Colorectal Cancer Cohort (NCRCC) study in China. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2024, 39, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkionis, I.G.; Flamourakis, M.E.; Tsagkataki, E.S.; Kaloeidi, E.I.; Spiridakis, K.G.; Kostakis, G.E.; Alegkakis, A.K.; Christodoulakis, M.S. Multidimensional analysis of the learning curve for laparoscopic colorectal surgery in a regional hospital: The implementation of a standardized surgical procedure counterbalances the lack of experience. BMC Surg. 2020, 20, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayne, D.; Pigazzi, A.; Marshall, H.; Croft, J.; Corrigan, N.; Copeland, J.; Quirke, P.; West, N.; Rautio, T.; Thomassen, N.; et al. Effect of robotic-assisted vs conventional laparoscopic surgery on risk of conversion to open surgery among patients undergoing resection for rectal cancer. JAMA 2017, 318, 1569–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miskovic, D.; Ni, M.; Wyles, S.M.; Tekkis, P.; Hanna, G.B. Learning curve and case selection in laparoscopic colorectal surgery: Systematic review and international multicenter analysis of 4852 cases. Dis. Colon Rectum 2012, 55, 1300–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, G.B.; Mackenzie, H.; Miskovic, D.; Ni, M.; Wyles, S.; Aylin, P.; Parvaiz, A.; Cecil, T.; Gudgeon, A.; Griffith, J.; et al. Laparoscopic colorectal surgery outcomes improved after National Training Program (LAPCO) for specialists in England. Ann. Surg. 2022, 275, 1149–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xynos, E.; Gouvas, N.; Triantopoulou, C.; Tekkis, P.; Vini, L.; Tzardi, M.; Boukovinas, I.; Androulakis, N.; Athanasiadis, A.; Christodoulou, C.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the surgical management of colon cancer: A consensus statement of the Hellenic and Cypriot Colorectal Cancer Study Group by the HeSMO. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2016, 29, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kolfschoten, N.E.; Van Leersum, N.J.; Gooiker, G.A.; Van De Mheen, P.J.; Eddes, E.H.; Kievit, J.; Brand, R.; Tanis, P.J.; Bemelman, W.A.; Tollenaar, R.A.; et al. Successful and safe introduction of laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery in Dutch hospitals. Ann. Surg. 2013, 257, 916–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odermatt, M.; Khan, J.; Parvaiz, A. Supervised training of laparoscopic colorectal cancer resections does not adversely affect short- and long-term outcomes: A propensity-score-matched cohort study. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 20, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelsen, C.A.; Neuenschwander, A.U.; Jansen, J.E.; Wilhelmsen, M.; Kirkegaard-Klitbo, A.; Tenma, J.R.; Bols, B.; Ingeholm, P.; Rasmussen, L.A.; Jepsen, L.V.; et al. Disease-free survival after complete mesocolic excision compared with conventional colon cancer surgery: A retrospective, population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, H.; Miskovic, D.; Ni, M.; Parvaiz, A.; Acheson, A.G.; Jenkins, J.T.; Griffith, J.; Coleman, M.G.; Hanna, G.B. Clinical and educational proficiency gain of supervised laparoscopic colorectal surgical trainees. Surg. Endosc. 2013, 27, 2704–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akiyoshi, T.; Kuroyanagi, H.; Ueno, M.; Oya, M.; Fujimoto, Y.; Konishi, T.; Yamaguchi, T. Learning curve for standardized laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer under supervision: Single-center experience. Surg. Endosc. 2011, 25, 1409–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staiger, R.D.; Rössler, F.; Kim, M.J.; Brown, C.; Trenti, L.; Sasaki, T.; Uluk, D.; Campana, J.P.; Giacca, M.; Schiltz, B.; et al. Benchmarks in colorectal surgery: Multinational study to define quality thresholds in anterior resections. Br. J. Surg. 2022, 109, 1274–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, I.; Ghignone, F.; Ugolini, G.; Ercolani, G.; Montroni, I.; Capelli, P.; Garulli, G.; Catena, F.; Lucchi, A.; Ansaloni, L.; et al. Emilia-Romagna Surgical Colorectal Cancer Audit (ESCA): A value-based healthcare retro-prospective study to measure and improve the quality of surgical care in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2022, 37, 1727–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.M.; Johnston, L.; Sarosiek, B.; Rogers, T.; Cohn, H.; Hedrick, T.L. Reducing readmissions while shortening length of stay: The positive impact of an enhanced recovery protocol in colorectal surgery. Dis. Colon. Rectum. 2017, 60, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleshman, J.; Branda, M.; Sargent, D.J.; Boller, A.M.; George, V.; Abbas, M.; Peters, W.R., Jr.; Maun, D.; Chang, G.; Herline, A.; et al. Effect of laparoscopic-assisted vs open resection of stage II/III rectal cancer on pathologic outcomes: ACOSOG Z6051. JAMA 2015, 314, 1346–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitano, S.; Inomata, M.; Sato, A.; Yoshimura, K.; Moriya, Y. Randomized controlled trial to evaluate laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer: Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG 0404. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 35, 475–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.B.; Park, J.W.; Jeong, S.Y.; Nam, B.H.; Choi, H.S.; Kim, D.W.; Lim, S.B.; Lee, T.G.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, J.S.; et al. Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid or low rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): Short-term outcomes of an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deijen, C.L.; Vasmel, J.E.; de Lange-de Klerk, E.S.; Cuesta, M.A.; Coene, P.P.; Lange, J.F.; Meijerink, W.J.; Jakimowicz, J.J.; Jeekel, J.; Kazemier, G.; et al. Ten-year outcomes of a randomised trial of laparoscopic vs open surgery for colon cancer. Surg. Endosc. 2017, 31, 2607–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitano, S.; Inomata, M.; Mizusawa, J.; Katayama, H.; Watanabe, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Ito, M.; Saito, S.; Fujii, S.; Konishi, F.; et al. Survival outcomes following laparoscopic versus open D3 dissection for stage II or III colon cancer (JCOG0404): A phase 3 randomized controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 2, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitous, C.A.; Ivatury, S.J.; Suwanabol, P.A. Value of Qualitative Research in Colorectal Surgery. Dis. Colon. Rectum. 2021, 64, 1444–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Pas, M.H.; Haglind, E.; Cuesta, M.A.; Fürst, A.; Lacy, A.M.; Hop, W.C.; Bonjer, H.J.; COLOR II Study Group. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer (COLOR II): Short-term outcomes of a randomized, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | LS (n = 71) | OS (n = 203) | Test Used (Statistic, df) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 64 ± 10 | 67 ± 11 | t(272) = 1.74 | 0.08 |

| Sex (male/female) | 32/39 | 121/82 | χ2(1) = 3.94 | <0.05 |

| BMI (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 25.5 ± 3.1 | 26.7 ± 3.6 | t(272) = 1.80 | 0.07 |

| * ASA ≥ III n (%) | 12 (17%) | 66 (33%) | χ2(1) = 6.01 | <0.05 |

| * Prior abdominal surgery n (%) | 8 (11%) | 42 (21%) | χ2(1) = 3.52 | 0.06 |

| * Multivisceral resection n (%) | 0 (0%) | 19 (9%) | Fisher’s Exact | <0.01 |

| * Tumor size (cm, mean ± SD) | 4.5 ± 1.8 | 5.3 ± 2.1 | t(272) = 2.40 | 0.02 |

| Tumor location (8 regions) | – | – | χ2(7) = 44.11 | <0.001 |

| Tumor staging (Tis–T4b) | – | – | χ2(5) = 16.72 | <0.01 |

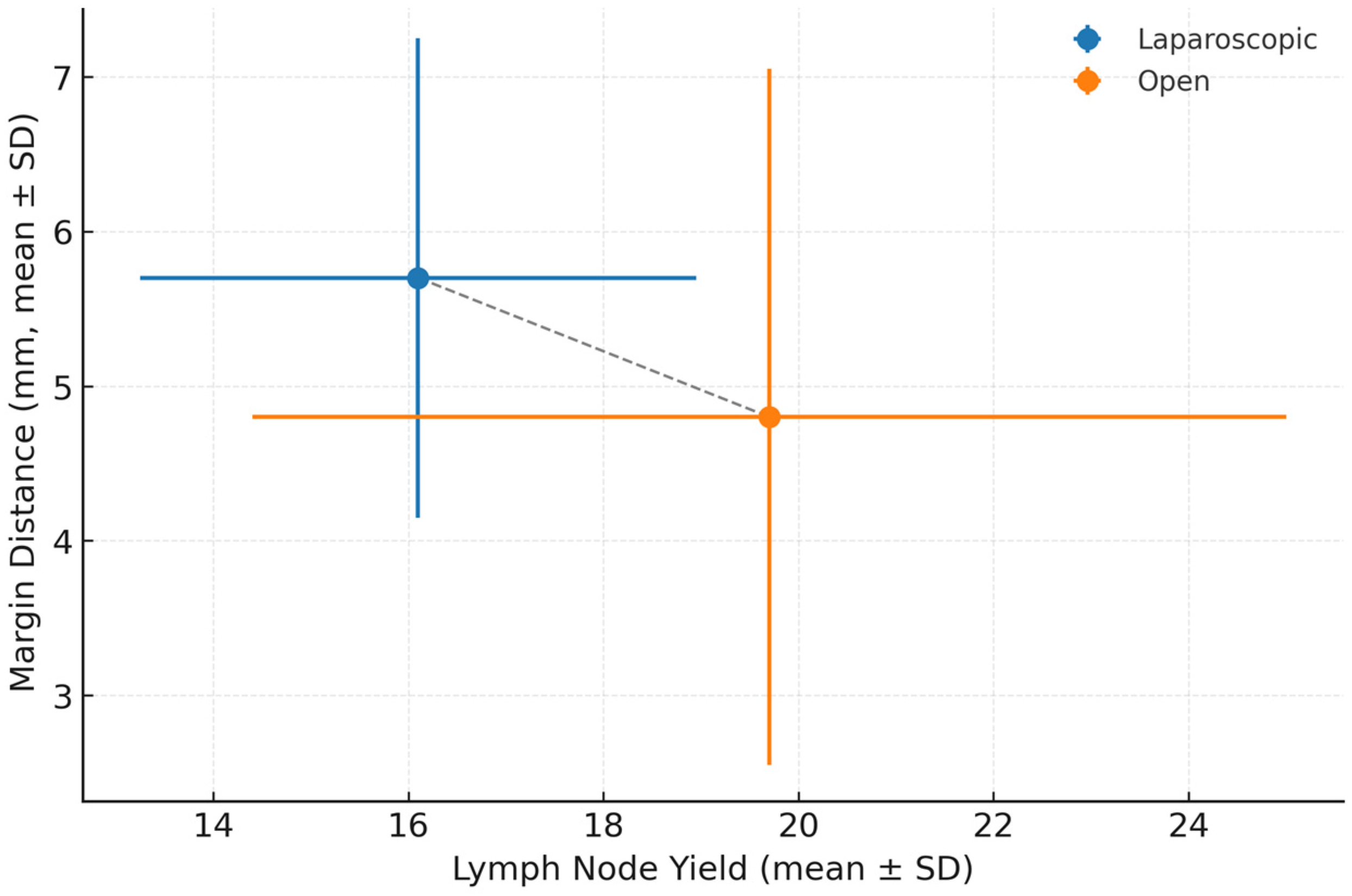

| Lymph nodes retrieved (mean ± SD) | 16.1 ± 5.7 | 19.7 ± 10.6 | Wilcoxon rank-sum (W = 8239.5) | <0.05 |

| N positive nodes (%) | 24 (34%) | 86 (42%) | χ2(1) = 1.28 | 0.26 |

| Margin distance (mm, mean ± SD) | 5.7 ± 3.1 | 4.8 ± 4.5 | Wilcoxon rank-sum (W = 5074.5) | <0.01 |

| Positive margin n (%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (5%) | Fisher’s Exact | 0.07 |

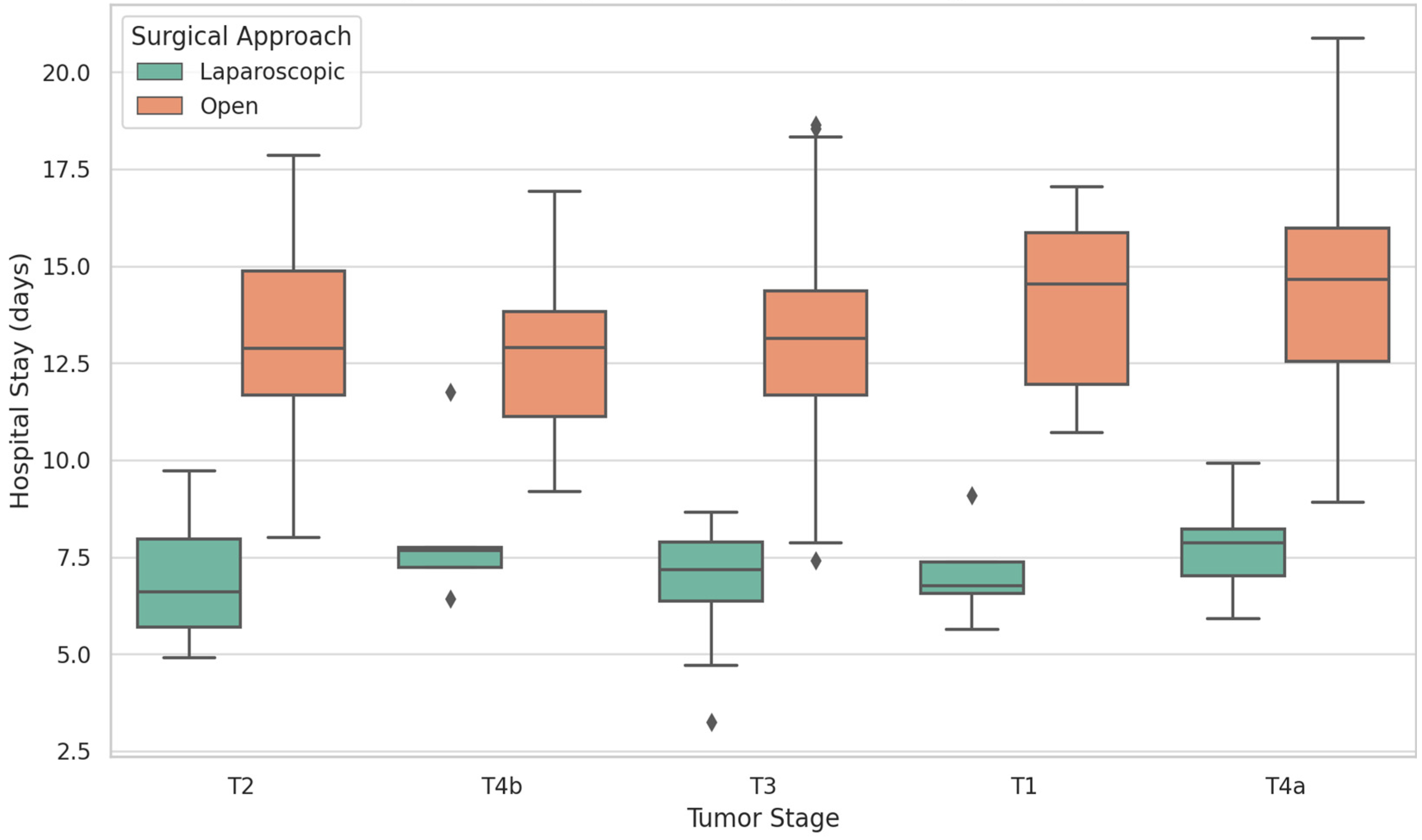

| Length of hospital stay (days, mean ± SD) | 7.1 ± 2.3 | 13.2 ± 6.8 | Wilcoxon rank-sum (W = 12,354) | <0.001 |

| * 30-day mortality n (%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1%) | Fisher’s Exact | 0.32 |

| * Conversion to open n (%) | 0 (0%) | – | – | – |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Slavu, I.; Tulin, R.; Dogaru, A.; Dima, I.; Slavu, C.O.; Popescu, M.; Nitescu, B.; Mutu, D.-E.G.; Tulin, A. A Retrospective Study Regarding the Implementation of Laparoscopy in Colon Cancer Through the Evaluation of Lymph Node Yield and Oncological Safety Margins in a Medium-Volume Center in Eastern Europe. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2570. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13102570

Slavu I, Tulin R, Dogaru A, Dima I, Slavu CO, Popescu M, Nitescu B, Mutu D-EG, Tulin A. A Retrospective Study Regarding the Implementation of Laparoscopy in Colon Cancer Through the Evaluation of Lymph Node Yield and Oncological Safety Margins in a Medium-Volume Center in Eastern Europe. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(10):2570. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13102570

Chicago/Turabian StyleSlavu, Iulian, Raluca Tulin, Alexandru Dogaru, Ileana Dima, Cristina Orlov Slavu, Marius Popescu, Bogdan Nitescu, Daniela-Elena Gheoca Mutu, and Adrian Tulin. 2025. "A Retrospective Study Regarding the Implementation of Laparoscopy in Colon Cancer Through the Evaluation of Lymph Node Yield and Oncological Safety Margins in a Medium-Volume Center in Eastern Europe" Biomedicines 13, no. 10: 2570. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13102570

APA StyleSlavu, I., Tulin, R., Dogaru, A., Dima, I., Slavu, C. O., Popescu, M., Nitescu, B., Mutu, D.-E. G., & Tulin, A. (2025). A Retrospective Study Regarding the Implementation of Laparoscopy in Colon Cancer Through the Evaluation of Lymph Node Yield and Oncological Safety Margins in a Medium-Volume Center in Eastern Europe. Biomedicines, 13(10), 2570. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13102570