Sphingolipid Metabolism Is Associated with Cardiac Dyssynchrony in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects and Study Protocol

2.2. Echocardiographic Assessments

2.3. Measurement of Sphingomyelin and Acid Ceramidase

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Concentrations of Acid Ceramidase and Sphingomyelin

3.2. Comparisons between Patients with Low and High Baseline Plasma Acid Ceramidase Concentrations

| AMI Group | Control Group | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 62 | n = 54 | ||

| Age, year | 55.4 ± 10.3 | 55.3 ± 7.4 | 0.264 |

| Sex (M/F) | 55/7 | 47/8 | 0.384 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dL | 191.6 ± 46.5 | 174.9 ± 23.4 | 0.014 * |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 41.4 ± 9.8 | 65.0 ± 14.4 | <0.001 ** |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 134.3 ± 38.8 | 97.2 ± 22.9 | <0.001 ** |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL | 89.0 ± 117.9 | 70.6 ± 36.8 | 0.239 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 156.3 ± 93.2 | 87.0 ± 7.7 | <0.001 ** |

| HbA1C, % | 6.5 ± 1.7 | 5.1 ± 0.3 | <0.001 ** |

| BUN, mg/dL | 15.9 ± 6.8 | 12.3± 2.9 | 0.019 * |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ±0.1 | <0.001 ** |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL | 452.9 ± 92.5 | 285.5 ± 51.1 | <0.001 ** |

| hsCRP(mg/L) | 0.46 ± 0.67 | 0.05 ± 0.04 | 0.003 * |

| oxLDL, mg/dL | 65.7± 21.8 | 51.8± 31.0 | 0.002 * |

| MCN (per cell) | 118.4 ± 103.4 | 194.9 ± 119.5 | 0.003 * |

| Sphingomyelin (mg/dL) | 16.8 ± 14.9 | 31.17 ± 8.57 | <0.001 ** |

| aCD (ng/mL) | 17.0 ± 8.09 | 43.48 ± 14.9 | <0.001 ** |

| Sphingomyelin/aCD | 1.19 ± 1.15 | 0.79 ± 0.32 | 0.010 * |

| Current smoking, % | 39(63%) | 2(4%) | <0.001 ** |

3.3. Comparisons between Patients with Low and High Baseline Sphingomyelin Concentrations

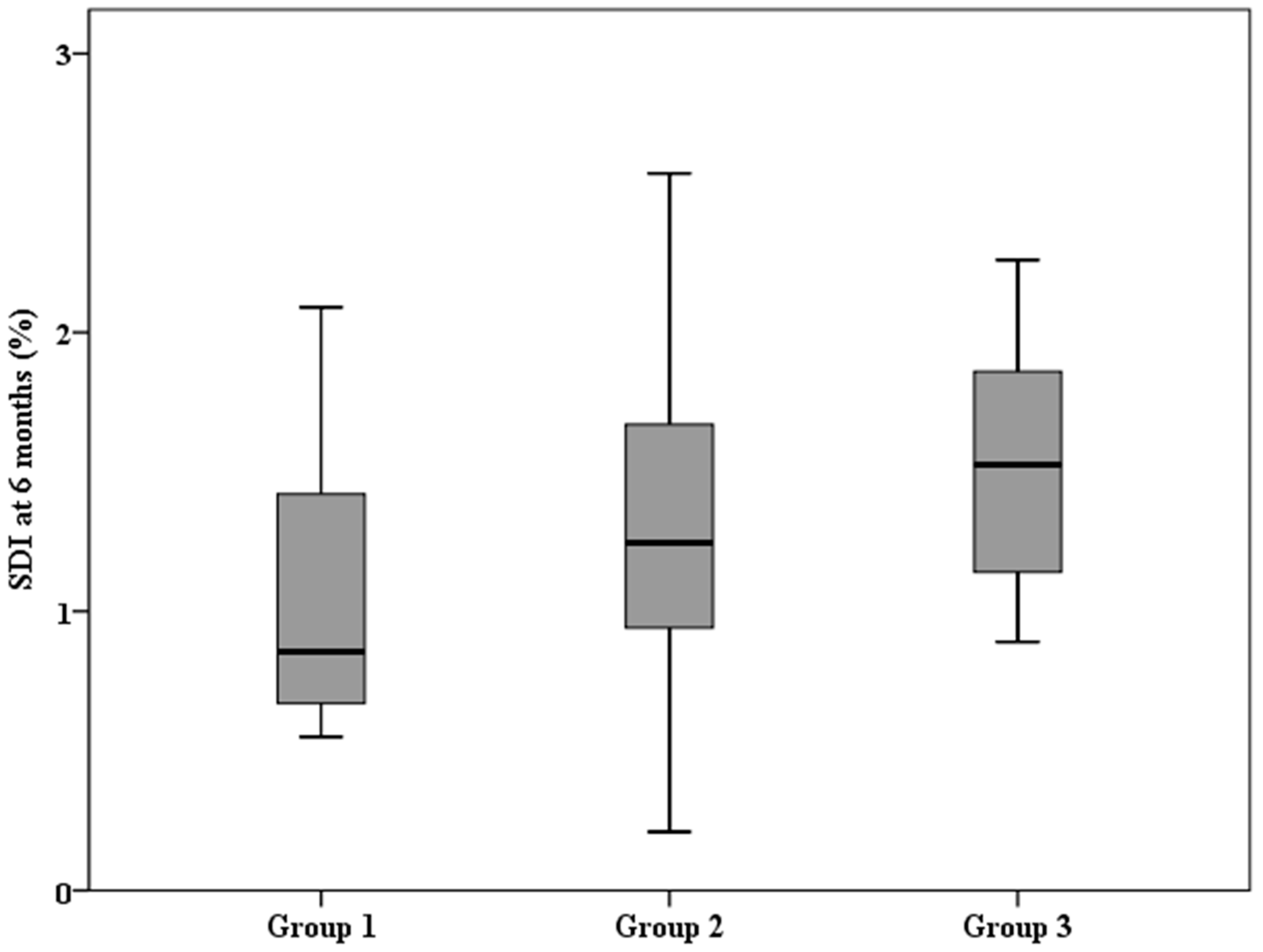

3.4. Trend Analysis Revealed That SDI Was Positively Proportional to Baseline Acid Ceramidase and Sphingomyelin Concentrations

3.5. Evaluation of Possible Predictors of Worsening SDI at 6 Months

4. Discussion

4.1. Sphingomyelin/Ceramide Pathway Metabolism and LV Dyssynchrony

4.2. The Yin/Yang Concept of Efficient Ceramide Metabolism

4.3. A Possible Reason for Lipid Metabolism and Heart Dyssynchrony

4.4. Plasma Levels of Acid Ceramidase and Sphingomyelin in AMI Patients

4.5. Research Strengths and Future Research Directions

4.6. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

6. Clinical Perspectives

- Patients with AMI with a higher baseline plasma sphingomyelin/acid ceramidase ratio had a significantly higher SDI at six months.

- We demonstrated that the ratio of sphingomyelin/acid ceramidase can be considered as a surrogate marker of plasma ceramide load or inefficient ceramide metabolism.

- Plasma sphingolipid pathway metabolism may be a new biomarker for therapeutic intervention to prevent adverse remodelling after AMI.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gomez-Larrauri, A.; Presa, N.; Dominguez-Herrera, A.; Ouro, A.; Trueba, M.; Gomez-Muñoz, A. Role of bioactive sphingolipids in physiology and pathology. Essays Biochem. 2020, 64, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinville, B.M.; Deschenes, N.M.; Ryckman, A.E.; Walia, J.S. A comprehensive review: Sphingolipid metabolism and implications of disruption in sphingolipid homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Echten-Deckert, G.; Herget, T. Sphingolipid metabolism in neural cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Biomembr. 2006, 1758, 1978–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Schuchman, E.H. Ceramide and Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. J. Lipids 2018, 2018, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klevstig, M.; Ståhlman, M.; Lundqvist, A.; Täng, M.S.; Fogelstrand, P.; Adiels, M.; Andersson, L.; Kolesnick, R.; Jeppsson, A.; Borén, J.; et al. Targeting acid sphingomyelinase reduces cardiac ceramide accumulation in the post-ischemic heart. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2016, 93, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Pendurthi, U.R.; Rao, L.V.M. Acid sphingomyelinase plays a critical role in LPS- and cytokine-induced tissue factor procoagulant activity. Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 2019, 134, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havulinna, A.S.; Sysi-Aho, M.; Hilvo, M.; Kauhanen, D.; Hurme, R.; Ekroos, K.; Salomaa, V.; Laaksonen, R. Circulating ceramides predict cardiovascular outcomes in the population-based FINRISK 2002 cohort. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2016, 36, 2424–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doehner, W.; Bunck, A.C.; Rauchhaus, M.; von Haehling, S.; Brunkhorst, F.M.; Cicoira, M.; Tschope, C.; Ponikowski, P.; Claus, R.A.; Anker, S.D. Secretory sphingomyelinase is upregulated in chronic heart failure: A second messenger system of immune activation relates to body composition, muscular functional capacity, and peripheral blood flow. Eur. Heart J. 2007, 28, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Kaddai, V.; Ching, J.; Fridianto, K.T.; Sieli, R.J.; Sugii, S.; Summers, S.A. A role for ceramides, but not sphingomyelins, as antagonists of insulin signaling and mitochondrial metabolism in C2C12 myotubes. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 23978–23988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadas, Y.; Vincek, A.S.; Youssef, E.; Żak, M.M.; Chepurko, E.; Sultana, N.; Sharkar, M.T.K.; Guo, N.; Komargodski, R.; Kurian, A.A.; et al. Altering sphingolipid metabolism attenuates cell death and inflammatory response after myocardial infarction. Circulation 2020, 141, 916–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yip, G.W.; Chan, A.K.; Wang, M.; Lam, W.W.; Fung, J.W.; Chan, J.Y.; Sanderson, J.E.; Yu, C.-M. Left ventricular systolic dyssynchrony is a predictor of cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction. Am. Heart J. 2008, 156, 1124–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nucifora, G.; Bertini, M.; Marsan, N.A.; Delgado, V.; Scholte, A.J.; Ng, A.C.; van Werkhoven, J.M.; Siebelink, H.-M.J.; Holman, E.R.; Schalij, M.J.; et al. Impact of left ventricular dyssynchrony early on left ventricular function after first acute myocardial infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 2010, 105, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo, O.; Cordeiro, F.; Gago, M.F.; Miltenberger-Miltenyi, G.; Ferreira, C.; Sousa, N.; Cunha, D. Fabry disease and the heart: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cianciulli, T.F.; Saccheri, M.C.; Rísolo, M.A.; Lax, J.A.; Méndez, R.J.; Morita, L.A.; Beck, M.A.; Kazelián, L.R. Mechanical dispersion in Fabry disease assessed with speckle tracking echocardiography. Echocardiography 2020, 37, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thygesen, K.; Alpert, J.S.; Jaffe, A.S.; Chaitman, B.R.; Bax, J.J.; Morrow, D.A.; White, H.D. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 237–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.M.; Bierig, M.; Devereux, R.B.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Pellikka, P.A.; Picard, M.H.; Roman, M.J.; Seward, J.; Shanewise, J.S.; et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: A report from the american society of echocardiography’s guidelines and standards committee and the chamber quantification writing group, developed in conjunction with the european association of echocardiography, a branch of the european society of cardiology. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2005, 18, 1440–1463. [Google Scholar]

- Kapetanakis, S.; Kearney, M.; Siva, A.; Gall, N.; Cooklin, M.; Monaghan, M. Real-time three-dimensional echocardiography: A novel technique to quantify global left ventricular mechanical dyssynchrony. Circulation 2005, 112, 992–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, J.S.; Jeong, M.H.; Lee, M.G.; Lee, S.E.; Kang, W.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Park, K.-H.; Sim, D.S.; Yoon, N.S.; Yoon, H.J.; et al. Left ventricular dyssynchrony after acute myocardial infarction is a powerful indicator of left ventricular remodeling. Korean Circ. J. 2009, 39, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, K.; Sayed, A.; Banach, M. Coenzyme Q10 reduces infarct size in animal models of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: A meta-analysis and summary of underlying mechanisms. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 857364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.H.; Kuo, C.L.; Huang, C.S.; Tseng, W.M.; Lian, I.B.; Chang, C.C.; Liu, C.S. High plasma coenzyme Q10 concentration is correlated with good left ventricular performance after primary angioplasty in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Medicine 2016, 95, e4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfield, T.L. Membrane lipids and CFTR: The Yin/Yang of efficient ceramide metabolism. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 202, 1074–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaurasia, B.; Summers, S.A. Ceramides in metabolism: Key lipotoxic players. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2021, 83, 303–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, A.I.; Haq, I.J.; Simpson, A.J.; Becker, K.A.; Gallagher, J.; Saint-Criq, V.; Verdon, B.; Mavin, E.; Trigg, A.; Gray, M.A.; et al. Recombinant acid ceramidase reduces inflammation and infection in cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 202, 1133–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coant, N.; Sakamoto, W.; Mao, C.; Hannun, Y.A. Ceramidases, roles in sphingolipid metabolism and in health and disease. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2017, 63, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Uhlig, S. The role of sphingolipids in respiratory disease. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2011, 5, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, A.; Moss, A.; Kokkotou, E.; Usheva, A.; Sun, X.; Cheifetz, A.; Zheng, Y.; Longhi, M.S.; Gao, W.; Wu, Y.; et al. CD39 and CD161 modulate Th17 responses in Crohn’s disease. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 3366–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirillo, F.; Piccoli, M.; Ghiroldi, A.; Monasky, M.M.; Rota, P.; La Rocca, P.; Tarantino, A.; D’Imperio, S.; Signorelli, P.; Pappone, C. The antithetic role of ceramide and sphingosine-1-phosphate in cardiac dysfunction. J. Cell. Physiol. 2021, 236, 4857–4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drevinge, C.; Karlsson, L.O.; Ståhlman, M.; Larsson, T.; Perman Sundelin, J.; Grip, L.; Andersson, L.; Borén, J.; Levin, M.C. Cholesteryl esters accumulate in the heart in a porcine model of ischemia and reperfusion. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, A.D.; Guido, M.C.; Tavares, E.R.; Carvalho, P.O.; Marques, A.F.; de Melo, M.D.T.; Salemi, V.M.C.; Kalil-Filho, R.; Maranhão, R.C. The expression of lipoprotein receptors is increased in the infarcted area after myocardial infarction induced in rats with cardiac dysfunction. Lipids 2018, 53, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samouillan, V.; Samper, I.M.M.D.L.; Amaro, A.B.; Vilades, D.; Dandurand, J.; Casas, J.; Jorge, E.; Calvo, D.d.G.; Gallardo, A.; Lerma, E.; et al. Biophysical and lipidomic biomarkers of cardiac remodeling post-myocardial infarction in humans. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulart, V.A.M.; Santos, A.K.; Sandrim, V.C.; Batista, J.M.; Pinto, M.C.X.; Cameron, L.C.; Resende, R.R. Metabolic disturbances identified in plasma samples from st-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients. Dis. Markers 2019, 2019, 7676189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Li, T.; Liu, Y.-W.; Zhang, L.; Dong, Z.-H.; Liu, S.-Y.; Gao, Y.-T. Plasma metabolic profile determination in young st-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients with ischemia and reperfusion: Ultra-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry for pathway analysis. Chin. Med. J. 2016, 129, 1078–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Chang, T.; Shi, C.; Wang, Y.; Ho, W.; Huang, H.; Chang, S.; Pan, K.; Chen, M. Liver x receptor/retinoid x receptor pathway plays a regulatory role in pacing-induced cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e009146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canals, D.; Perry, D.M.; Jenkins, R.W.; Hannun, Y.A. Drug targeting of sphingolipid metabolism: Sphingomyelinases and ceramidases. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 694–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikas, P.; Chalikias, G.; Tziakas, D. Cardiovascular implications of sphingomyelin presence in biological membranes. Eur. Cardiol. Rev. 2018, 13, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaggini, M.; Sabatino, L.; Vassalle, C. Conventional and innovative methods to assess oxidative stress biomarkers in the clinical cardiovascular setting. BioTechniques 2020, 68, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaggini, M.; Pingitore, A.; Vassalle, C. Plasma ceramides pathophysiology, measurements, challenges, and opportunities. Metabolites 2021, 11, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Low Baseline aCD | High Baseline aCD | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (≤14.28 ng/mL; n = 31) | (>14.28 ng/mL; n = 31) | p-Value | |

| Age (years) | 55.25 ± 11.93 | 60.58 ± 11.59 | 0.073 |

| Sex (Male/female) | 29/2 | 26/5 | 0.082 |

| CPK, μ/L | 1995.84 ± 1742.19 | 2684.59 ± 2269.83 | 0.178 |

| CKMB, ng/mL | 204.71 ± 174.80 | 260.22 ± 206.84 | 0.248 |

| Troponin I, ng/mL | 4.04 ± 8.62 | 6.70 ± 20.21 | 0.545 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.04 ± 0.38 | 0.96 ± 0.22 | 0.357 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dL | 189.61 ± 41.88 | 193.48 ± 51.16 | 0.742 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 40.81 ± 9.53 | 42.03 ± 10.18 | 0.624 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 132.76 ± 36.66 | 135.78 ± 41.20 | 0.756 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL | 97.94 ± 152.83 | 80.36 ± 70.67 | 0.552 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 144.23 ± 86.81 | 168.29 ± 99.11 | 0.313 |

| HbA1C, % | 6.20 ± 1.43 | 6.79 ± 1.94 | 0.164 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.99 ± 3.07 | 26.24 ± 3.95 | 0.172 |

| Risk factors | |||

| Hypertension | 26(84%) | 20(65%) | 0.039 * |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7(23%) | 12(39%) | 0.062 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 30(96%) | 28(90%) | 0.310 |

| Smoking | 21(68%) | 18(58%) | 0.880 |

| Infarct-related artery | 0.774 | ||

| LAD | 17(53%) | 18(60%) | |

| LCX | 5(16%) | 3(10%) | |

| RCA | 10(31%) | 9(30%) | |

| SDI baseline (%) | 1.11 ± 0.65 | 1.58 ± 1.21 | 0.079 |

| SDI 6M (%) | 1.24 ± 0.59 | 2.19 ± 1.97 | 0.026 * |

| LVEF baseline (%) | 63.6 ± 8.7 | 57.5 ± 12.1 | 0.038 * |

| LVEF 6M (%) | 65.8 ± 10.5 | 59.1 ± 11.8 | 0.031 * |

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 0.25 ± 0.29 | 0.64 ± 0.86 | 0.022 * |

| oxLDL (mg/dL) | 57.64 ± 19.62 | 72.18 ± 22.79 | 0.046 * |

| CyPA (ng/mL) | 52.97 ± 20.37 | 67.06 ± 26.90 | 0.021 * |

| TIMI risk score | 2.41 ± 0.87 | 3.21 ± 1.15 | 0.007 ** |

| Sphingomyelin (mg/dL) | 17.23 ± 10.38 | 16.40 ± 18.47 | 0.833 |

| Sphingomyelin/aCD | 1.68 ± 1.32 | 0.70 ± 0.69 | 0.001 ** |

| Low Baseline Sphingomyelin | High Baseline Sphingomyelin | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (≤12.67 mg/dL; n = 31) | (>12.67 mg/dL; n = 31) | p-Value | |

| Age (years) | 61.10 ± 12.42 | 55.17 ± 11.51 | 0.060 |

| Sex (Male/female) | 27/4 | 28/3 | 0.723 |

| CPK, μ/L | 2307.03 ± 2021.92 | 2200.52 ± 2059.64 | 0.842 |

| CKMB, ng/mL | 223.47 ± 177.35 | 225.31 ± 204.18 | 0.970 |

| Troponin I, ng/mL | 5.39 ± 11.04 | 6.14 ± 20.43 | 0.876 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.00 ± 0.25 | 1.02 ± 0.38 | 0.826 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dL | 175.59 ± 38.06 | 203.97 ± 51.51 | 0.020 * |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 41.53 ± 10.34 | 41.79 ± 8.49 | 0.920 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 122.79 ± 31.05 | 142.09 ± 44.40 | 0.056 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL | 56.37 ± 33.23 | 124.17 ± 164.38 | 0.034 * |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 150.46 ± 94.49 | 153.90 ± 85.14 | 0.886 |

| HbA1C, % | 6.44 ± 1.75 | 6.39 ± 1.48 | 0.912 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.81 ± 3.04 | 26.00 ± 4.03 | 0.217 |

| Risk factors | |||

| Hypertension | 20(65%) | 26(84%) | 0.039 * |

| Diabetes mellitus | 9(29%) | 10(32%) | 0.787 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 28(90%) | 30(97%) | 0.310 |

| Smoking | 19(61%) | 20(65%) | 0.603 |

| Infarct-related artery | 0.588 | ||

| LAD | 17(54%) | 18(58%) | |

| LCX | 4(13%) | 4(13%) | |

| RCA | 10(33%) | 9(29%) | |

| LVEF baseline (%) | 60.17 ± 11.62 | 63.12 ± 9.22 | 0.318 |

| LVEF 6M (%) | 62.35 ± 12.21 | 64.61 ± 10.58 | 0.482 |

| SDI baseline (%) | 1.55 ± 1.30 | 1.14 ± 0.62 | 0.149 |

| SDI 6M (%) | 1.96 ± 2.10 | 1.36 ± 0.52 | 0.183 |

| Apo B | 89.1 ± 17.33 | 103.73 ± 24.25 | 0.010 * |

| oxLDL (mg/dL) | 57.64 ± 19.62 | 72.18 ± 22.79 | 0.017 * |

| OLAB (U/L) | 392.62 ± 403.44 | 217.47 ± 177.88 | 0.048 * |

| aCD (ng/mL) | 16.99 ± 6.29 | 16.79 ± 10.04 | 0.928 |

| Sphingomyelin/aCD | 0.50 ± 0.35 | 1.88 ± 1.26 | <0.001 ** |

| B | SE | p-Value | Odds Ratio | 95%CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.016 | 0.032 | 0.622 | 1.016 | 0.954 | 1.082 |

| Gender | −0.619 | 1.094 | 0.572 | 0.59 | 0.063 | 4.594 |

| oxLDL | −0.009 | 0.020 | 0.678 | 0.992 | 0.953 | 1.032 |

| CoQ10 | −3.501 | 3.973 | 0.378 | 0.030 | 0.000 | 72.637 |

| CKMB mass | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.194 | 1.003 | 0.999 | 1.007 |

| Sphingomyelin/aCD | 0.817 | 0.393 | 0.038 * | 2.263 | 1.047 | 4.890 |

| IRA | −0.291 | 0.397 | 0.463 | 0.747 | 0.343 | 1.626 |

| IL-6 | 0.070 | 0.042 | 0.095 | 1.073 | 0.988 | 1.165 |

| Constant | −0.964 | 3.266 | 0.768 | 0.381 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, C.-H.; Kuo, C.-L.; Cheng, Y.-S.; Huang, C.-S.; Liu, C.-S.; Chang, C.-C. Sphingolipid Metabolism Is Associated with Cardiac Dyssynchrony in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1864. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12081864

Huang C-H, Kuo C-L, Cheng Y-S, Huang C-S, Liu C-S, Chang C-C. Sphingolipid Metabolism Is Associated with Cardiac Dyssynchrony in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. Biomedicines. 2024; 12(8):1864. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12081864

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Ching-Hui, Chen-Ling Kuo, Yu-Shan Cheng, Ching-San Huang, Chin-San Liu, and Chia-Chu Chang. 2024. "Sphingolipid Metabolism Is Associated with Cardiac Dyssynchrony in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction" Biomedicines 12, no. 8: 1864. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12081864

APA StyleHuang, C.-H., Kuo, C.-L., Cheng, Y.-S., Huang, C.-S., Liu, C.-S., & Chang, C.-C. (2024). Sphingolipid Metabolism Is Associated with Cardiac Dyssynchrony in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. Biomedicines, 12(8), 1864. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12081864