Successful Introduction of Benralizumab for Eosinophilic Ascites

Abstract

:1. Introduction

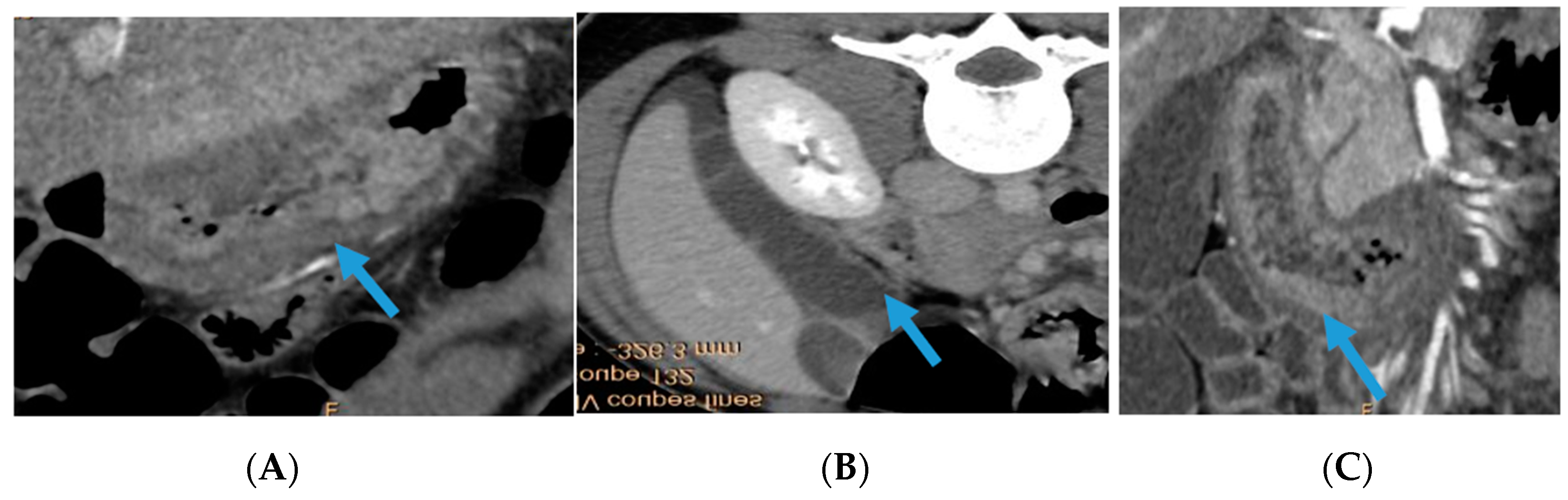

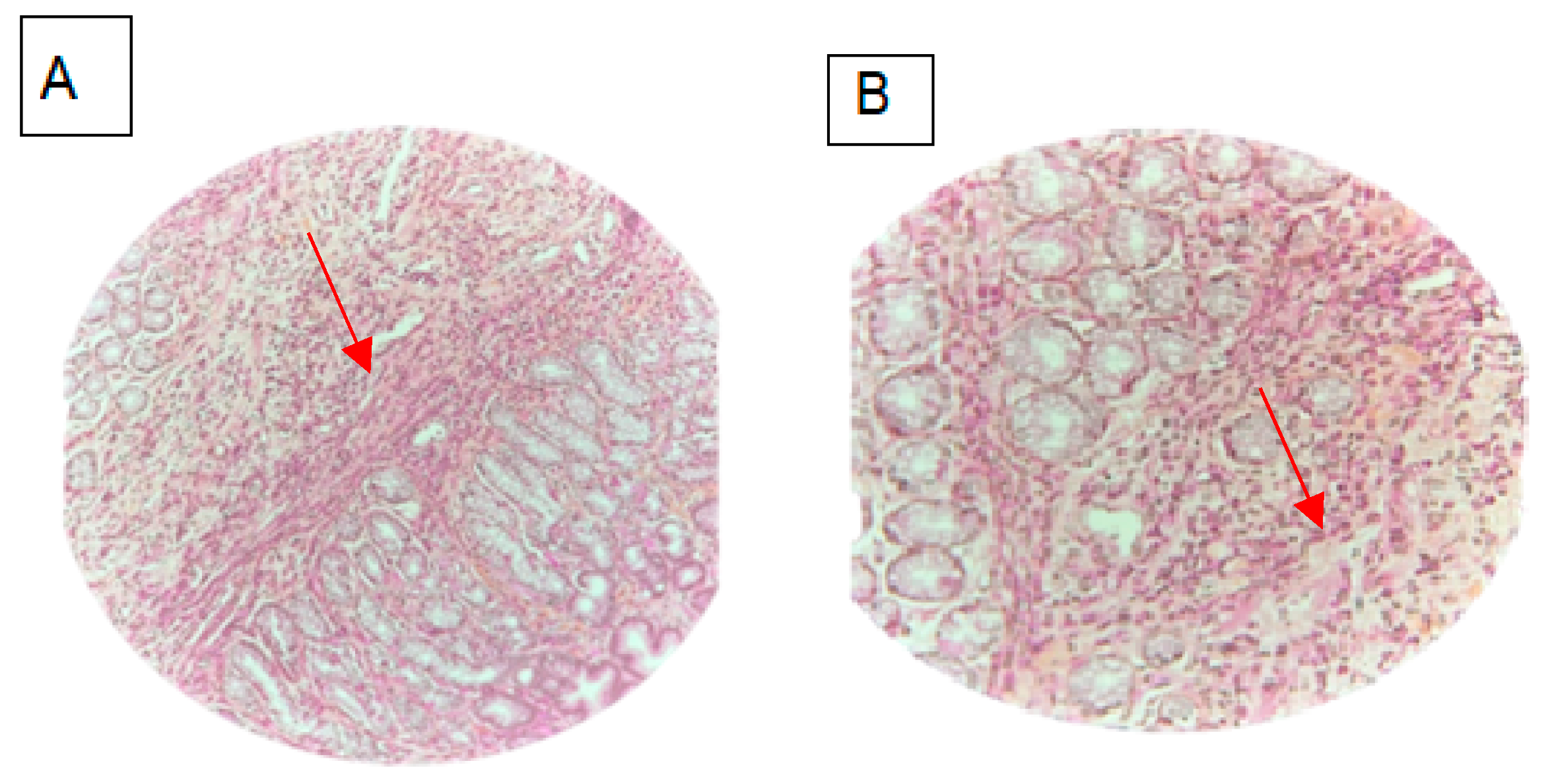

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pinte, L.; Baicuş, C. Causes of eosinophilic ascites—A systematic review. Rom. J. Intern. Med. Rev. Roum. Med. Interne 2019, 57, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hepburn, I.S.; Sridhar, S.; Schade, R.R. Eosinophilic ascites, an unusual presentation of eosinophilic gastroenteritis: A case report and review. World J. Gastrointest. Pathophysiol. 2010, 1, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineton de Chambrun, G.; Gonzalez, F.; Canva, J.Y.; Gonzalez, S.; Houssin, L.; Desreumaux, P.; Cortot, A.; Colombel, J.F. Natural history of eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 9, 950–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, N.C.; Hargrove, R.L.; Sleisenger, M.H.; Jeffries, G.H. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Medicine 1970, 49, 299–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Lagos Maldonado, A.; Alcazar Jaén, L.M.; Benavente Fernández, A. Eosinophilic ascites: A case report. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Engl. Ed. 2018, 41, 372–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, F.L.; De Melo, M.S.; Makiya, M.; Kumar, S.; Brown, T.; Wetzler, L.; Ware, J.M.; Khoury, P.; Collins, M.H.; Quezado, M.; et al. Benralizumab Completely Depletes Gastrointestinal Tissue Eosinophils and Improves Symptoms in Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2022, 10, 1598–1605.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbdullGaffar, B. Eosinophilic effusions: A clinicocytologic study of 12 cases. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2018, 46, 1015–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunkara, T.; Rawla, P.; Yarlagadda, K.S.; Gaduputi, V. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: Diagnosis and clinical perspectives. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 2019, 12, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Rached, A.; El Hajj, W. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: Approach to diagnosis and management. World J. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 7, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, Y. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: A state-of-the-art review. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 32, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talley, N.J.; Shorter, R.G.; Phillips, S.F.; Zinsmeister, A.R. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: A clinicopathological study of patients with disease of the mucosa, muscle layer, and subserosal tissues. Gut 1990, 31, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, S.; Vohra, S.; Rawat, S.; Kashyap, V. Eosinophilic ascites: A diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2016, 8, 656–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roufosse, F. Targeting the Interleukin-5 Pathway for Treatment of Eosinophilic Conditions Other than Asthma. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrett, J.K.; Jameson, S.C.; Thomson, B.; Collins, M.H.; Wagoner, L.E.; Freese, D.K.; Beck, L.A.; Boyce, J.A.; Filipovich, A.H.; Villanueva, J.M.; et al. Anti-interleukin-5 (mepolizumab) therapy for hypereosinophilic syndromes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2004, 113, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FitzGerald, J.M.; Bleecker, E.R.; Nair, P.; Korn, S.; Ohta, K.; Lommatzsch, M.; Ferguson, G.T.; Busse, W.W.; Barker, P.; Sproule, S.; et al. Benralizumab, an anti-interleukin-5 receptor α monoclonal antibody, as add-on treatment for patients with severe, uncontrolled, eosinophilic asthma (CALIMA): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016, 388, 2128–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, F.L.; Legrand, F.; Makiya, M.; Ware, J.; Wetzler, L.; Brown, T.; Magee, T.; Piligian, B.; Yoon, P.; Ellis, J.H.; et al. Benralizumab for PDGFRA-Negative Hypereosinophilic Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1336–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M.L.; Collins, M.H.; Villanueva, J.M.; Kushner, J.P.; Putnam, P.E.; Buckmeier, B.K.; Filipovich, A.H.; Assa’ad, A.H.; Rothenberg, M.E. Anti-IL-5 (mepolizumab) therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 118, 1312–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuko, L.; Bilaj, F.; Bega, B.; Barbullushi, A.; Resuli, B. Eosinophilic ascites, as a rare presentation of eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Hippokratia 2014, 18, 275–277. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, A.A.; Barbosa, S.M.; Oliveira, S.; Ramada, J.; Silva, A. Subserous Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis: A Rare Cause of Ascites. Eur. J. Case Rep. Intern. Med. 2017, 4, 000586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.; Morgado, F.; Blanco, C.; Parreira, J.; Costa, J.; Rodrigues, L.; Marfull, L.; Cardoso, P. Ascites in a Young Woman: A Rare Presentation of Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis. Case Rep. Gastrointest. Med. 2018, 2018, 1586915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Zheng, K.; Shen, H. Eosinophilic ascites: An unusual manifestation of eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2020, 35, 765–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.Q.; Chen, X.; Chen, S.L. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis with abdominal pain and ascites: A case report. World J. Clin. Cases 2021, 9, 4238–4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Ray, A.; Montasser, A.; El Ghannam, M.; El Ray, S.; Valla, D. Eosinophilic ascites as an uncommon presentation of eosinophilic gastroenteritis: A case report. Arab. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 22, 184–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cuko, L [18] 2014 | Agrawal, Shefali [12] 2016 | Ferreira, António- Araújo [19] 2017 | Martín-Lagos Maldonado, Alicia [5] 2018 | Santos, Carina [20] 2018 | Feng, Wan [21] 2020 | Tian, Xiao-Qing [22] 2021 | El Ray, Ahmed [23] 2021 | Our Case | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Woman | Woman | Woman | Man | Woman | Man | Man | Woman | Woman |

| Age | 37 | 34 | 41 | 35 | 32 | 26 | 34 | 30 | 16 |

| Abdominal pain | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Diarrhea | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + |

| Abdominal distension | - | - | + | - | + | + | - | + | + |

| Nausea | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | + |

| Blood eosinophil count | 4.94 G/L | 11.9 G/L | 3.454 G/L | 2.969 G/L | 4.88 G/L | 8.2 G/L | 4.85 G/L | 9.45 G/L | 13.0 G/L |

| Intestinal wall thickening | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Ascitic fluid analysis | 94% Eo | 100% Eo | Inflammatory liquid with predominance of Eo | 95% Eo | 93.3% Eo | High eosinophil count | - | 90% Eo | 89% Eo |

| Endoscopic findings | Normal | Eosinophilic gastritis and duodenitis | Normal | Normal | Eosinophilic colitis | Eosinophilic gastritis and colitis | Eosinophilic colitis | Normal | Eosinophilic duodenitis and colitis |

| Treatment | Prednisone (40 mg/d than 15 mg/d) | Prednisone (25 mg/d) | Prednisone (40 mg/d) | Prednisone (25 mg/d) | Prednisone (40 mg/d) | Prednisone (40 mg/d) | Prednisone (40 mg/d) 6 months | Prednisone (40 mg/d) 1 month | Prednisone (30 mg/d) 3 months |

| Outcome | improvement | improvement | relapse | improvement | improvement | improvement | improvement | improvement | Relapse |

| Follow-up | ND | 2 years | ND | 2 months | ND | ND | 1 year | 3 months | 4 years |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Belfeki, N.; Ghriss, N.; Zayet, S.; El Hedhili, F.; Moini, C.; Lefevre, G. Successful Introduction of Benralizumab for Eosinophilic Ascites. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12010117

Belfeki N, Ghriss N, Zayet S, El Hedhili F, Moini C, Lefevre G. Successful Introduction of Benralizumab for Eosinophilic Ascites. Biomedicines. 2024; 12(1):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12010117

Chicago/Turabian StyleBelfeki, Nabil, Nouha Ghriss, Souheil Zayet, Faten El Hedhili, Cyrus Moini, and Guillaume Lefevre. 2024. "Successful Introduction of Benralizumab for Eosinophilic Ascites" Biomedicines 12, no. 1: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12010117

APA StyleBelfeki, N., Ghriss, N., Zayet, S., El Hedhili, F., Moini, C., & Lefevre, G. (2024). Successful Introduction of Benralizumab for Eosinophilic Ascites. Biomedicines, 12(1), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12010117