‘Some Animals Are More Equal Than Others’: The Hierarchy of Citizenship in Austria

Abstract

:1. Introduction

‘No one believes more firmly than Comrade Napoleon that all animals are equal.’—George Orwell.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Citizenship

a status bestowed on those who are full members of a community. All who possesses the status are equal with respect to the rights and duties which with the status is endowed. There is no universal principle that determines what those rights and duties shall be, but societies in which citizenship is a developing institution create an image of an ideal citizenship against which achievement can be measured and towards which aspiration can be directed. The urge forward along the path thus plotted is an urge towards a fuller measure of equality, an enrichment of the stuff of which the status is made and an increase in the number of those on whom the status is bestowed.

2.2. Citizenship and ‘Race’ Connection

2.3. Fiction and Social Reality: Austria

2.4. State of the Art in Literature: Austria

3. Methodology

3.1. Methodological Theory

3.2. Methods—Participants Descriptions

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Methods—Central Interview Question

- How does your ‘racial’ or ‘ethnic background’ have bearing on your rights as an Austrian citizen?

3.5. Methods—Identification of Themes, Coding and Analysis

4. Findings

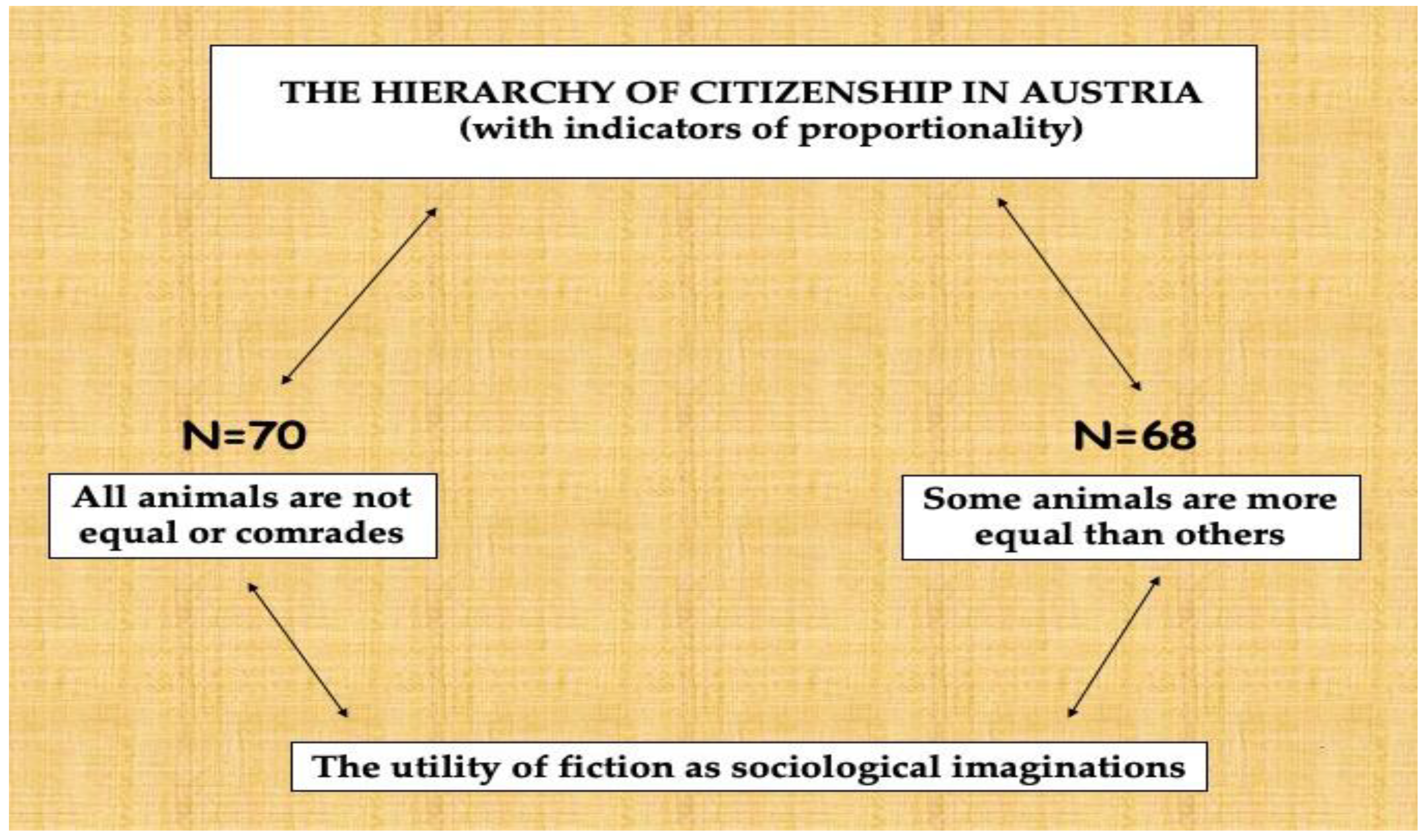

4.1. All Animals are Not Equal or Comrades (n = 70)

‘Black-is-black. Whether you have an Austrian passport or not, ‘egal’ [it doesn’t matter]. But if you are white Austrian from here and there [other European countries], ‘whiteness’ opens doors for you’.[Male, Black African background]

‘I think people with darker skin are most discriminated against. Black Africans…well that sounds stupid, but the fact is people from northern Africa are classified [as] different again from other Africans…but they are all blacks…’.[Female, Turkish background]

‘I think the ones who are easily identified [as outsiders] are the ones with the most differences to themselves. Yes, Africans, the ones who mirror [represent] the biggest difference’..[Female, German background]

‘For example, I have a friend from [Kenya]…a nurse. She says that sometimes in the hospital patients shout at her: “Don’t touch me! Don’t touch me!” She only wants to prepare them to get an injection…or something like that…but they tell her: “Don’t touch me!” Because she is black. If she is white from God-knows-where, they wouldn’t see the colour and they wouldn’t say: “Don’t touch me!”…’.[Female, Black African background]

4.2. Some Animals Are More Equal Than Others (n = 68)

‘…my opinion is that [some] people suffer less discrimination because they are white. [Followed by] Turkish people and Arabs and other immigrant background [who] also have an advantage over black people. Even if they’ve just an ordinary visa in their hands and are newcomers. Because of skin colour…they are better off than black Austrians’.[Male, Black African background]

‘I just remember one time while shopping someone [openly] addressed me as ‘Piefke’… and I said to myself, “Oh now it happens even to me!” ...But I can’t compare it to what other immigrants suffer…for example, my husband [is] from Nigerian origin’.[Female, German background]

‘Passport’ will not help you with anything. You have the citizenship and still have no respect from people… What does that mean? It means that your ‘passport’ is divided into two, you know… If your passport is halved that also means your ration as an Austrian is halved... The epic thing is that a brother with a passport, university degree, and all that…is lower than a Kosovo man or a Turkish man, or some ‘halal meat’ from Arab… that may only have training in how to slaughter ram or cut onions and make kebab…. I don’t know how to describe it… but the real whites are like kings, the other fake whites are their royal servants and…blacks are common slaves’.[Male, Black African background]

‘All whites think they are better than people from my homeland [Turkey]. Blacks unfortunately I must say are at the floor [bottom]. It’s true…. Everyone is ranked [laughed at] like in the military’.[Male, Turkish background]

5. Discussion

In dichotomies crucial for the practice and the vision of social order the differentiating power hides as a rule behind one of the members of the opposition. Both sides depend on each other, but this dependence is not symmetrical. The second side depends on the first for its contrived and enforced isolation. The first depends on the second for its self-assertion.

“…there was a black woman, a cleaner in their company. The cooks, Turkish, were harassing her till she left work after a month. I tried to help her but because the ‘cooks’ were more in number and so had more ‘power’, she decided to resign”[Female, Turkish background]

6. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aburabia, Rawia. 2017. Trapped between national boundaries and patriarchal structures: Palestinian Bedouin women and polygamous marriage in Israel. Journal of Comparative Family Studies 48: 339–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agozino, Biko. 2018. Black Women and the Criminal Justice System: Towards the Decolonisation of Victimisation. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Akrivopoulou, Christina M. 2013. Citizen and Citizenship in the Era of Globalization: Theories and Aspects of the Classic and Modern Citoyen. In Digital Democracy and the Impact of Technology on Governance and Politics: New Globalized Practices: New Globalized Practices. Edited by Christina Akrivopoulou and Nicolaos Garipidis. Hershey: IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, Michelle. 2012. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Bridget. 2013. Us and Them?: The Dangerous Politics of Immigration Control. Oxford: OUP Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Banton, Michael. 1998. Racial Theories. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2013. Modernity and Ambivalence. Cambridge: Polity Press. First published 1991. [Google Scholar]

- BBC. 2016. ‘David Alaba’. Available online: http://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/football/35842558 (accessed on 24 April 2017).

- Bellamy, Richard. 2008. Citizenship: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo, and David G. Embrick. 2001. Are Blacks Color Blind Too?: An Interview-Based Analysis of Black Detroiters’ Racial Views. Race and Society 4: 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, Rogers. 1992. Citizenship and Nationhood in France and Germany. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, Alan. 2012. Social Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, Callie Harbin, Simons Roland L, and Gibbons Frederick X. 2012. Racial Discrimination, Ethnic-Racial Socialization, and Crime: A Micro-sociological Model of Risk and Resilience. American Sociological Review 77: 648–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byerman, K. 2019. Talking Back: Phillis Wheatley, Race and Religion. Religions 10: 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappetti, C. 1993. Writing Chicago: Modernism, Ethnography, and the Novel. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, David. 2008. 1. Narrative Explanation and Its Malcontents. History and Theory 47: 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, Christopher, and Neil Nevitte. 2014. Scapegoating: Unemployment, Far-right Parties and Anti-immigrant Sentiment. Comparative European Politics 12: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Code, Lorraine. 1991. What Can She Know?: Feminist Theory and the Construction of Knowledge. New York: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, Enzo, and Paola Rebughini. 2016. Intersectionality and Beyond. Rassegna Italiana di Sociologia 57: 439–60. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, Enzo, Leonini Luisa, and Rebughini Paola. 2009. Different but Not Stranger: Everyday Collective Identifications Among Adolescent Children of Immigrants in Italy. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35: 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlstedt, Magnus, and Vicktor Vesterberg. 2017. Citizens in the Making: The Inclusion of Racialized Subjects in Labour Market Projects in Sweden. Scandinavian Political Studies 40: 228–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlstedt, Magnus, Runqvist Mikael, and Vesterberg Vicktor. 2017. Citizenship—Rights, Obligations and Changing Citizenship Deals. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/9148828/Citizenship_Rights_Obligations_and_Changing_Citizenship_Ideals (accessed on 18 November 2017).

- Domingues, Jose Mauricio. 2017. From Citizenship to Social Liberalism or Beyond? Some Theoretical and Historical Landmarks. Citizenship Studies 21: 167–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, James T. 1954. Some Observation on Literature and Sociology. In Reflections at Fifty and other Essays. Edited by James T. Farrell. New York: Vanguard Press, pp. 142–55. [Google Scholar]

- Favell, Adrian. 1998. A Politics that is Shared, Bounded, and Rooted? Rediscovering Civic Political Culture in Western Europe. Theory and Society 27: 209–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrajoli, Luigi. 2001. Fundamental Rights. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law 14: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogiel-Bijaoui, Sylvie. 2016. The Cosmopolitan Future: A Feminist Approach. Laws 5: 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, Craig J., Howat Holly, Pei Lai K, Forsyth York A, Asmus Gary, and Stokes Billy R. 2013. Examining the infractions causing higher rates of suspensions and expulsions: Racial and ethnic considerations. Laws 2: 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, Ira N., Francisco Rivera-Batiz, and Myeong-Su Yun. 2002. Economic Strain, Ethnic Concentration and Attitudes towards Foreigners in the European Union. Available online: http://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/21350/1/dp578.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2014).

- Gärtner, Reinhold. 2017. The FPÖ, foreigners, and Racism in the Haider Era. In The Haider Phenomenon in Austria. Edited by Ruth Wodak and Anton Pelinka. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, pp. 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ghafournia, Nafiseh, and Patricia Easteal. 2018. Are Immigrant Women Visible in Australian Domestic Violence Reports that Potentially Influence Policy? Laws 7: 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, John. 2007. Fiction and the Weave of Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy, Paul. 1987. There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack: The Cultural Politics of Race and Nation. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn, Evelyn Nakano. 2009. Unequal Freedom: How Race and Gender Shaped American Citizenship and Labor. London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glezakos, Stavroula. 2012. Truth and Reference in Fiction. In The Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Language. Edited by Gillian Russel and Delia Graff Fara. London: Routledge, pp. 177–85. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 1990. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Doubleday. First published 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales Rose, Jasmine B. 2017. Toward a Critical Race Theory of Evidence. Minnesota Law Review 101: 2016–29. [Google Scholar]

- Graber, Jennifer. 2019. Natives Need Prison: The Sanctification of Racialized Incarceration. Religions 10: 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazard, Anthony Q. 2011. A Racialized Deconstruction? Ashley Montagu and the 1950 UNESCO statement on race. Transforming Anthropology 19: 174–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipfl, Brigitte, and Daniela Gronold. 2011. Asylum Seekers as Austria’s Other: The Re-Emergence of Austria’s Colonial Past in a State-of-exception. Social Identities 17: 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipp, John R., and Charis E. Kubrin. 2017. From bad to worse: How changing inequality in nearby areas impacts local crime. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 3: 129–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, Helmut, Titelbach Gerlinde, and Winter-Ebmer Rudolf. 2014. Wage Discrimination against Immigrants in Austria? (No. 1406). Working Paper. Linz: Department of Economics, Johannes Kepler University of Linz. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, Kenneth. 2014. Policing the Borders of the ‘Centaur State’: Deportation, Detention, And Neoliberal Transformation Processes—The Case of Austria. Social Inclusion 2: 113–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Hsiu-Fang, and Sarah E. Shannon. 2005. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research 15: 1277–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huddleston, Thomas, and Jasper D. Tjaden. 2012. Immigrant Citizens Survey. How Immigrants Experience Integration in 15 European Cities. Brussels: Joint publication of the King Baudouin Foundation and the Migration Policy Group. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, Suleman. 2015. A Binary Model of Broken Home: Parental Death-Divorce Hypothesis of Male Juvenile Delinquency in Nigeria and Ghana. In Contemporary Perspectives in Family Research. Edited by Sheila Royo Maxwell and Sampson Lee Blair. New York: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, vol. 9, pp. 311–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kranz, Dani. 2017. Changing Measures of the Quantum of Sufficient Germanness: Access to German Citizenship of Children of German/Non-German Parentage, and Children Eligible under Jus Soli Provisions. Journal of Comparative Family Studies 48: 367–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyzanowski, Michal. 2017. The Politics of Exclusion: Debating Migration in Austria. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, Gloria. 2010. Just What is Critical Race Theory and What’s It Doing in a Nice Field Like Education? International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 11: 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavee, Einat, and Orly Benjamin. 2017. Between Social Rights and Human Rights: Israeli Mothers’ Right to be Protected from Poverty and Prostitution. Journal of Comparative Family Studies 48: 315–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, Suleman. 2019a. Just married: the synergy between feminist criminology and the Tripartite Cybercrime Framework. International Social Science Journal, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, Suleman. 2019b. Where Is the Money? The Intersectionality of the Spirit World and the Acquisition of Wealth. Religions 10: 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, Suleman. 2019c. Betrayals in Academia and a Black Demon from Ephesus. Wisdom in Education 9: 3. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, Suleman, and Geoffrey U. Okolorie. 2019. The bifurcation of the Nigerian cybercriminals: Narratives of the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) agents. Telematics and Informatics 40: 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, Suleman I., Michael Rush, Edward T. Dibiana, and Claire P. Monks. 2017. Gendered penalties of divorce on remarriage in Nigeria: A qualitative study. Journal of Comparative Family Studies 48: 351–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, Mariano. 2015. Fiction and Social Reality: Literature and Narrative as Sociological Resources. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Malkki, Liisa H. 1997. Purity and Exile. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, Thomas Humphrey. 1950. Citizenship and Social Class and Other Essays. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, Thomas Humphrey, and Thomas Bottomore. 1992. Citizenship and Social Class. London: Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Messinger, Irene. 2013. There is something about marrying… The case of human rights vs. migration regimes using the example of Austria. Laws 2: 376–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, Charles Wright. 2000. The Sociological Imagination. Oxford: Oxford University Press. First published 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt, Ursula, Linda P. Juang, and Moin Syed. 2018. “We don’t do that in Germany!” A critical race theory examination of Turkish heritage young adults’ school experiences. Ethnicities, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudde, Cas. 2012. The Relationship between Immigration and Nativism in Europe and North America. Washington, DC: 10th Anniversary MPI Migration Policy Institute, pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Nationality Act. 1985. Federal Law Concerning Austrian Nationality. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/5c863d394.html (accessed on 22 February 2017).

- Orwell, Gorge. 1955. Animal Farm. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Robert E., and Ernest W. Burgess. 1921. Introduction to the Science of Sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pechar, Hans. 2015. Austria: From Legacy to Reform. Education in the European Union: Pre-2003 Member States 1: 21. [Google Scholar]

- Pepper, Andrew. 2017. Race, violence and neoliberalism: crime fiction in the era of Ferguson and Black Lives Matter. Textual Practice, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perchinig, Bernhard, and Tobias Troger. 1990. Migrationshintergrund als Differenzkategorie. Vom Notwendigen Konfliket Zwischen Theorie und Empirie in der Migrationsforschung. In Zukunft. Werte. Europa. Die Europäische Wertestudie 1990. Edited by Polak Regina. Wien: Böhlau. [Google Scholar]

- Permoser, Julia Mourão, and Sieglinde Rosenberger. 2016. Religious citizenship as a substitute for immigrant integration? The governance of diversity in Austria. In Illiberal Liberal States. London: Routledge, pp. 149–64. [Google Scholar]

- Philips, Coretta, and Lucinda Platt. 2016. ‘Race’ and Ethnicity. In 2016 Social Advantage and Disadvantage. Edited by Hartley Dean and Lucinda Platt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Platt, Lucinda. 2002. Parallel Lives? Poverty among Ethnic Minority Groups in Britain. (No. 107). London: Child Poverty Action Group. [Google Scholar]

- Platt, Lucinda. 2016. Class, Capital and Social Mobility. In 2016 Social Advantage and Disadvantage. Edited by Hartley Dean and Lucinda Platt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Polanco, Mieka Brand. 2015. Punishment and the State: Imprisonment, Transgressions, Scapegoats, and the Contributions of Anthropology: An Introduction. PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review 38: 200–3. [Google Scholar]

- Policek, Nicoletta, Ravagnani Luisa, and Romano Carlo. 2019. Victimization of young foreigners in Italy. European Journal of Criminology, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polkinghorne, Donald. 1988. Narrative Knowing and the Human Sciences. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Redfield, Robert. 1962. Social Science among the Humanities. In Human Nature and the Study of Society: The Papers of Robert Redfield. Edited by Margaret Park Redfield. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, Vol. I, pp. 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Refaie, Elisabeth. 2001. Metaphors We Discriminate By: Naturalized Themes in Austrian Newspaper Articles About Asylum Seekers. Journal of Sociolinguistics 5: 352–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichel, David. 2012. Regulating Political Incorporation of Immigrants–Naturalisation Rates in Europe. Vienna: International Centre for Migration Policy Development. [Google Scholar]

- Reichel, David, and Bernhard Perchinig. 2015. Reflections on the value of citizenship-explaining naturalisation practices/Der Wert der Staatsbürgerschaft: Zur empirischen Erklärung von Einbürgerungspraxen. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft 44: 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiner, Robert. 2016. Crime, the Mystery of the Common-Sense Concept. London: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Rheindorf, Markus, and Wodak Ruth. 2019. ‘Austria First ’revisited: A diachronic cross-sectional analysis of the gender and body politics of the extreme right. Patterns of Prejudice 53: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rush, Michael, and Suleman I. Lazarus. 2018. ‘Troubling’ Chastisement: A Comparative Historical Analysis of Child Punishment in Ghana and Ireland. Sociological Research Online 23: 177–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shutes, Isabel. 2016. Citizenship and Migration. In 2016 Social Advantage and Disadvantage. Edited by Hartley Dean and Lucinda Platt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, Patrick, Piché Victor, and Gagnon Amélie. 2015. Social Statistics and Ethnic Diversity. Cross-National Perspectives in Classifications and Identity Politics. IMISCOE Research Series; Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Miri. 2014. Challenging a Culture of Racial Equivalence. The British Journal of Sociology 65: 107–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stambolis-Ruhstorfer, Michael. 2013. Labels of love: How migrants negotiate (or not) the culture of sexual identity. American Journal of Cultural Sociology 1: 321–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supik, Linda. 2014. Statistik und Rassismus. Das Dilemma der Erfassung von Ethnizität. Frankfurt: Campus. [Google Scholar]

- Torry, Malcolm. 2016. Religious advantage and disadvantage. In 2016 Social Advantage and Disadvantage. Edited by Hartley Dean and Lucinda Platt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Toscano, Mario Aldo. 2011. Introduzione. In Altre Sociologie: Undici Lezioni Sulla vita e la Convivenza. Milan: Angeli, pp. 9–39. [Google Scholar]

- Triger, Zvi. 2012. Fear of the Wandering Gay: some reflections on citizenship, nationalism and recognition in same-sex relationships. International Journal of Law in Context 8: 268–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tynes, Brendesha M., Joshua Schuschke, and Safiya Umoja Noble. 2016. Digital intersectionality theory and the black matter movement. In The Intersectional Internet: Race, Sex, Class, and Culture Online. Edited by Safiya Umoja Noble and Brendesha M. Tynes. Berlin: Peter Lang International Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 1969. ‘Four Statements on the Race Question’. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001229/122962eo.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2015).

- Vacchelli, Elena, and Eleonore Kofman. 2017. Towards an inclusive and gendered right to the city. Cities 76: 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warming, Hanne. 2019. Trust and Power Dynamics in Children’s Lived Citizenship and Participation: The Case of Public Schools and Social Work in Denmark. Children & Society 33: 333–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wodak, Ruth, and Bernd Matouschek. 1993. We are Dealing with People whose Origins One can clearly Tell just by Looking’: Critical Discourse Analysis and the Study of Neo-Racism in Contemporary Austria. Discourse & Society 4: 225–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, Patrick. 2017. Race and Citizenship. Available online: https://cico3dotcom.files.wordpress.com/2016/02/wolfe-patrick-2004-22race-and-citizenship22.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2017).

- Zaslove, Andrej. 2004. Closing the door? The ideology and Impact of Radical Right Populism on Immigration Policy in Austria and Italy. Journal of Political Ideologies 9: 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Znaniecki, Florian. 1934. The Method of Sociology. New York: Rinehart. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | It is noteworthy that a few contemporary endeavours (e.g., Lazarus 2019b; Pepper 2017) are beginning to recognise the value of fiction as tools of analysis in social science, and increasingly, this type of creative interventions seems to be gaining traction particularly, in sociology. |

| 2 | Concerning the “sociological imagination” here, while for Mills ([1959] 2000), the reconciliation is mainly between two social realities—the individual and society, for this article, alongside the above author’s idea, the reconciliation is also between fictional reality and social reality. |

| 3 | The author obtained ethical approval from the Royal Holloway University of London. |

| 4 | Concerning Muslims, ‘in Austria, the Federal Constitution provides a guarantee of freedom of religion in general and also the right to manifest one’s religion in private and in public as long as this does not conflict with public order and customs’ (Permoser and Rosenberger 2016, p. 149). However, the law only affords a limited scope for protecting the privileges and rights of oppressed minority groups, not the least because relational processes generally situate minority religious groups as inferior and position the majority as superior with regards to their citizenry entitlements. |

| 5 | Halal meat is the meat which adheres to Islamic law and involves the slaughtering of animals or poultry through a cut to the jugular vein, carotid artery, and windpipe. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lazarus, S. ‘Some Animals Are More Equal Than Others’: The Hierarchy of Citizenship in Austria. Laws 2019, 8, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws8030014

Lazarus S. ‘Some Animals Are More Equal Than Others’: The Hierarchy of Citizenship in Austria. Laws. 2019; 8(3):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws8030014

Chicago/Turabian StyleLazarus, Suleman. 2019. "‘Some Animals Are More Equal Than Others’: The Hierarchy of Citizenship in Austria" Laws 8, no. 3: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws8030014

APA StyleLazarus, S. (2019). ‘Some Animals Are More Equal Than Others’: The Hierarchy of Citizenship in Austria. Laws, 8(3), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws8030014