This subsection describes the principal characteristics of classical, neoclassical, and relational contract law, the latter having recently gained traction in the construction field. C such as discreteness, presentation, contract incompleteness, flexibility, and solidarity are discussed, as well as their application to the field of construction.

2.1.2. Neoclassical Contract Law

The emergence of concepts such as good faith—an anti-presentiation and anti-discrete notion (

MacNeil 1978)—coupled with the desire for greater flexibility to adjust to unforeseeable problems that will inevitably arise over the course of a relationship, are characteristics of neoclassical contract law. Long-term arrangements in a complex industry facing conditions of uncertainty render the use of presentiation techniques practically impossible because of the contract’s inherently incomplete nature (

Hart 2003;

MacNeil 1974a;

Williamson 1979) and the contract planner’s quest for flexibility (

MacNeil 1978). Because all future contingencies for which adaptation will be required cannot be fully anticipated at the beginning of the transaction, a different contracting framework that enables the preservation of the relationship and therefore of the exchange, while also providing an additional governance structure, had to emerge.

Neoclassical contract law mainly concerns flexibility—a way to structure the exchange and the evolution of the key stakeholders’ relationship—which could lead to cost and time savings in future disputes (

Nystén-Haarala et al. 2010). The use of standards, direct determination of performance by third parties, one-party control of terms, cost, and agreements to agree are considered flexible mechanisms of neoclassical contract law (

MacNeil 1978). External standards are not usually controlled by either of the parties or by an unrelated entity or party. Balance needs to be struck between sufficient flexibility and too much flexibility to ensure that parties will not have to repeatedly negotiate values or performance. Examples of external standards include certification agencies, such as the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), or the National Building Code of Canada, and the norms they produce.

Direct third-party determination of performance, while not offering a guarantee of smooth performance in the context of construction projects (

MacNeil 1978), refers to the use of an expert to determine contract content or performance. To this end, Macneil extensively cites the example of the architect’s role under the American Institute of Architects standardized construction contracts because of their role in determining the general administration of the contract. To this we could add engineering firms’ control of general contractors’ performance in terms of certifying when a project reaches a certain stage, such as substantial completion. The same goes for the mediation and arbitration process for the harmonization of conflicts affecting a relationship, which offers a less formal procedural approach than litigation, with the arbitrator being able to frequently interrupt witnesses with questions in an informal education process, thereby enabling the parties to proceed more intelligently with the case (

Fuller 1963). Continuity, or at least the completion of the contract, is therefore presumed in an arbitration process (

Williamson 1979), which is not always the case with litigation. In cases where external standards and direct third-party determination of performance mechanisms are not used, the contract may designate one party to define parts of the relationship, such as termination mechanisms (

MacNeil 1978). Even if this is considered to be a more relational approach, this mechanism still has a heavy weight in the power balance, or imbalance, of the relationship.

Cost can also be looked at as being a flexible mechanism if it provides compensation to the supplier for the expenses incurred in the production of the good or service, to which additional fees can be added, such as an anticipated overhead, with or without a definition of what is a cost (

MacNeil 1978). Cost-plus contracts, as opposed to fixed-price contracts, are a prime example of a flexibility mechanism, because the contractors’ expenses are all covered plus additional payments to allow a level of profit. Finally, agreements to agree refer to parties expressing their willingness to participate in a future process of expression of will (

MacNeil 1978). The inherent incomplete nature of long-term arrangements can lead parties to agree on details of the relationship’s performance at the time it best suits them. However, because there are no guarantees that parties will agree to terms at said time, contract drafters should prepare an alternative to fill the gaps of the contract.

Redetermination and renegotiation mechanisms represent other flexibility mechanisms (

Crocker and Reynolds 1993) and are considered to be viable options in uncertain or changing market conditions that could potentially affect the contractual relationship, as is the case in long-term arrangements (

Crocker and Masten 1991;

Nystén-Haarala et al. 2010). Redetermination implies the reassessment, or change, of a value or direct measurement of performance, as predetermined in the contract. On the other hand, renegotiation means changing the agreed-upon contract terms through a new negotiation and therefore concerns the decision-making process, which is an organic way of dealing with changes and uncertainties as opposed to more mechanical redetermination mechanisms. In a way, redetermination mechanisms could be linked to the use of external standards, cost measures, or the unilateral control of terms by a party, whereas renegotiation mechanisms relate to third-party direct determination of performance and agreements to agree. Contracts including renegotiation modalities should specify what is to happen in the event no agreement is reached between the parties (

Alleman et al. 2014). Flexibility measures are essential because of the incomplete nature of long-term arrangements and are considered to be the most cost-effective form of governance for this type of contract (

Campbell and Harris 1993).

Neoclassical contract law tries to move away from presentiation and discreteness by acting upon flexibility and recognizing the conflict between planning for all future contingencies and the inevitable changes that will occur throughout a relationship and by being willing to take action when such changes arise instead of only awarding monetary judgments (

MacNeil 1978). In other words, neoclassical contract law focuses more on the preservation of the relationship than its classical counterpart. However, this system has been proven to have shortcomings when the self-interest or other motivations of the parties impede the continuation of the relationship. Because the overall structure of neoclassical contract law resembles classical contract law, it can be unsuitable for dealing with relational issues (

MacNeil 1978).

2.1.3. Relational Contract Law

A classic way to look at the financial records of a company is to consider the balance sheet as a snapshot of what the company owns and owes at a specific moment in time, whereas the income statement is more of a video showing the income and expenses generated during a given period (

Levitt 1998). The same analogy applies to the main difference between neoclassical contract law and relational contract law. In neoclassical contracts, the reference point for raised issues concerning changes is the original agreement or the framed picture of the initial contract, whereas relational approaches use the entire relation and the way it has evolved up to the time of the change issue arising—a video of the relationship evolution (

MacNeil 1978;

Williamson 1979). Increasingly long and complex contracts and the necessity to sustain long-term relationships have led to the displacement of neoclassical contract law by the more transaction-specific, ongoing administrative adjustment process of relational contract law in which discreteness and presentiation become just another decision factor (

MacNeil 1978;

Williamson 1979).

Relational contract theory is derived from empirical works led by Macaulay (

Macaulay 1963), as well as Beale and Dugdale (

Beale and Dugdale 1975), before being theorized by Macneil (

MacNeil 1980a). It was found that contract law is often not followed in business transactions and that it might be substituted with non-legal norms, such as bargaining power (

Macaulay 1963). Informal social controls are therefore seen as complements to formal controls and even sometimes supplant them (

Black 1976;

Ellickson 1994;

Granovetter 1985). Parties use incomplete contracts and undetailed planning and avoid legal remedies because of their flexible nature (

Beale and Dugdale 1975). Macneil conceptualized the relational approach, which he describes as a “mini society with a vast array of norms beyond those centered on the exchange and its immediate processes” (

MacNeil 1978)—a different paradigm of contracts and contract law (

Belley 1998). In his theory, Macneil assumes the existence of 10 common contractual norms—meaning ways parties must or should behave during the exchange—interpreted according to a discrete/relational spectrum: role integrity, reciprocity, planning, effectuation of consent, flexibility, solidarity, cohesive norms (restitution, reliance, and expectation), power, propriety of means, and harmonization with the social matrix (

MacNeil 1980a). Of these norms, two are considered to be more discrete: implementation of planning and effectuation of consent, which in turn he renames as discreteness and presentiation. He also singles out five particularly relational norms: role integrity, preservation of the relationship (derived from solidarity), harmonization of relational conflict (derived from harmonization with the social matrix), propriety of means, and supra-contractual norms, which refers to broader norms, such as distributive and procedural justice, liberty, human dignity, and social equality (

MacNeil 1978,

1980a,

1983). Relational norms can be internal, internalized, or external (

Macneil and Campbell 2001). Internal norms concern the contract terms and the development and evolution of obligations during the actual relationship, whereas external norms are found in the context and environment surrounding the relationship, such as in the regulatory framework for the procurement of work and professional services. Mandatory obligations derived from the regulatory framework and included in the contract are of an internalized nature (

Jobidon et al. 2018).

A fully relational contractual arrangement has defining characteristics. Communications between parties are not limited to the formal linguistic form but instead are informal, deep, and extensive. Parties find satisfaction not only in the economic exchange, but also in the complex and personal social exchange. The nature of the exchange is difficult to monetize, and the commencement and termination of the relationship is gradual. The planning focus is mainly on the structures and processes of the relationship with limited specific planning of substance. Mutual planning is important, as parties are not likely to adhere to contractual terms without bargaining and will try to jointly develop such planning. Tacit assumptions are an aspect of relational planning and a precondition to a relationship’s survival. Part of the planning might be binding, but a degree of tentativeness will remain with respect to some or all of the terms. Future cooperation regarding planning and performance is anticipated and considered necessary to a successful long-term arrangement. The benefits and burdens deriving from the exchange shall be shared and undivided. Sources of obligations are both external and internal to the relationship, which may also develop obligations itself. Obligations are usually nonspecific, non-measurable, and of a restorative nature. The number of parties to the arrangement will likely be more than two but will often include more stakeholders or parties, which are expected to behave in altruistic fashion. Instead of the presentiation expected in a transactional exchange, relational arrangements futurize the present and anticipate troubles and conflicts as a normal feature of a long-term contract, which should be dealt with using cooperative and restorative measures (

MacNeil 1974b,

1978).

Contract law has seen a paradigm shift from freedom to morality, transaction to relationship, fragmentation to integration, and from the closing to the opening of the system (

Rolland 1998). Individualism and antagonism now leave room for collaboration and solidarity in dynamic, complex, and ever-changing economies—a phenomenon partly created by division and specialization of labor (

Durkheim 1893). According to Durkheim, social harmony results from the division of labor, which is “characterized by a cooperation which is automatically produced through the pursuit in each individual of his own interests. It suffices that each individual consecrate himself to a special function in order, by the force of events, to make himself solidary with others” (

Durkheim 1893). More specifically, Durkheim refers to the notion of organic solidarity, which is a form of necessary trust based on the interdependence of highly specialized roles in a complex system of division of labor requiring the cooperation of all the groups and individuals in society (

Durkheim 1893). Construction contracts are a prime example of the necessity of organic solidarity, as they are characterized by an ever-growing number of key stakeholders involved in the production process. These include architects, engineers, general contractors, construction managers, representatives from public entities, end users, and others who need to cooperate and trust each other during the long-term arrangement binding them.

2.1.4. Relational Contract Law in Different Fields

Even if the roots of relational contract theory are deeply embedded in sociolegal and sociological theory, it has been utilized in many fields, such as law, economics, governance, marketing, management, and, specifically, construction management. Each will be treated in this order.

Belley (

1991,

2000) distinguishes his work from that of Macneil by inscribing it in the legal pluralism current, which proceeds from the assumption of a plurality of legal orders whose interaction, whether complementary or conflicting, would be manifested in contractual practices and contract representation. According to Belley, relational contract theory presents a very rich, and perhaps too rich, representation of the sociological reality to the detriment of the coherence of the legal analysis. Although he criticizes some aspects of Macneil’s theory, he still mostly abides by it throughout his analysis of the role of law and legal institutions in the regional supply department. His study reveals the rather marginal role of state contract law and court law as planning instruments or as methods of conflict resolution and states that trust, flexibility, and the desire to preserve the commercial relationship are the prime factors to which parties agree in a compromise (

Belley 1991). He also claims in his later work that problems confronting public and private law cannot find a judicial or administrative solution without the express consideration of standards that are proven, presumed, or deemed to be constitutive of the relevant social context (

Belley 2011). Researchers have also tried to operationalize Macneil’s theory. Campbell and Harris attempted to create a testable model of the cooperative attitudes and behavior of parties to a long-term contract. Their model could offer a potentially more interesting explanation than the individual utility-maximization model, therefore rejecting classical law when explaining long-term arrangements and endorsing relational contract law as the appropriate framework for their studies (

Campbell and Harris 1993).

Goetz and Scott analyzed the issue in greater depth by examining contractual language usually found in relational agreements: a “best efforts” standard of performance and a discretionary termination privilege (

Goetz and Scott 1981). In complex and uncertain economies, parties will more frequently rely on interactive and dynamic contractual arrangements because of the difficulty of circumscribing, analyzing, or identifying risks associated with contingencies, therefore complexifying the ex-ante negotiation process. The capacity of humans to respond to external complexity and uncertainty can be extremely costly and sometimes render the quest for presentiation impossible for parties that are inherently rationally bound (

Simon 1957). Despite these premises, Goetz and Scott advance that parties to a long-term contract are still seeking cost minimization, because the “best efforts” concept can be translated into an expected level of effort needed by the parties in order to maximize the net joint product resulting from the relationship, especially in a context where performance is not precisely specified (

Goetz and Scott 1981). To achieve maximum output, parties should use appropriate monitoring mechanisms, such as a discretionary termination provision, which act as risk allocation mechanisms. The authors suggest that even if courts seem to understand the relationship between “best efforts” and termination, the legal doctrine is still uncertain and ambiguous. The reconciliation of the two could facilitate the drafting of these types of mechanisms in complex and uncertain contexts while also giving the courts the opportunity to understand the mechanisms’ inherent tension and the policies meant to regulate them (

Goetz and Scott 1981).

Other researchers have investigated the role of court intervention, whether passive or active, in areas of contract law. Schwartz found four factors making courts inclined to activism (

Schwartz 1992): (1) The contract formation process or the course of performance affects process values, such as asymmetric information and parties not being commercially sophisticated or facing monopoly power; (2) third parties are affected by the enforcement of the contract; (3) a substantially unfair outcome results from the contract; and (4) the incomplete contract is completed by the court with terms that parties will accept and the court will apply. Relational contracts often do not satisfy the first and fourth factors, because parties are usually commercially sophisticated and because the incomplete nature of the contract derives from missing, incomplete, or asymmetric information, and parties looking for legal enforcement will usually reject terms relying on unverifiable or unobservable information. The author suggests that contract theorists now explain contract content as the echoing parties’ foresight of the possibility of renegotiation. Moreover, because parties are not able to predict all future risks associated with contingencies, they will create “structures” that will enable them to answer these contingencies in a desirable fashion. Schwartz concludes that regulatory caution is probably justified by the suggestion that relational contracts are efficient structures for the governance of commercial exchange and that judicial passivity may facilitate the parties’ behavior in this context. He also notes that imminent regulatory attention to relational contracts might need further study (

Schwartz 1992). The notion of “structures” is essential for the analysis of public construction projects and the content of professional services contracts. The actual behavior of parties not being part of the present study, our focus is placed on relational governance structures and mechanisms present in the contract language and serving as foundations for the development of the long-term relationship.

Researchers have suggested where future research regarding relational contract theory should be focused. Feinman suggests that future research should be concentrated towards further fragmenting analysis, such as the possibility of commercial construction contracting, rather than extending Macneil’s general theory of contracts. Standardized contracts repeatedly used by recurrent or occasional parties of different sizes and sophistication, between which interactions in a variety of settings occur and difficulties surely arise, are considered by Macneil to be a premium choice for the application of relational contract theory (

Feinman 2000). On the other hand, Gudel came to the realization that the limitation of legal techniques has led to a growing interest in alternative dispute resolution, mediation, and counseling, which are interested not only in extending a relationship’s norms, but also in giving structure and order to a clash of power. He therefore invited future researchers to investigate how the law could be made a more effective instrument for reinforcing contract norms (

Gudel 1998). Only a few scholars in the legal field have addressed these pleas for scholarly attention (

Harries and Vincent-Jones 2001;

Stipanowich 1998;

Sweet 1997;

Vincent-Jones and Harries 1998;

Vincent-Jones 2012).

Stipanowich analyzed the transactional features of the procurement system and concluded that genuine systemic reform, from the transactional framework to a more collective, cooperative, and relational framework, is essential in an era of evolving delivery systems that is witnessing a shift in roles and relationships (

Stipanowich 1998). The United Kingdom’s competitive tendering system has been analyzed by researchers looking to evaluate the transactional or relational nature of the system. They found that, while the procurement process is prone to transactional tendencies, relational techniques, such as (1) framework agreements implying the awarding of contracts to the same provider over a number of tendering rounds, (2) the negotiation of details after the decision to award the tender, (3) the use of approved lists, and (4) the importance of reputation and past dealings of tendering parties, could be used to counterbalance these tendencies (

Macneil and Campbell 2001;

Vincent-Jones 2012). The lack of trust affecting the compulsory procurement system was found, among others reasons, to lead to contractual problems (

Vincent-Jones and Harries 1998). Studies have also focused on the application of relational contract law in the context of housing management and legal services and found that voluntary tendering, such as greater choice for public authorities and more flexible timeframes and selection criteria procedures, which facilitate cooperative relationships, presents more relational features than its compulsory counterpart (

Harries and Vincent-Jones 2001;

Macneil and Campbell 2001;

Vincent-Jones and Harries 1998;

Vincent-Jones 2012). Jobidon et al. analyzed the procurement legislation, regulations, and context of three jurisdictions using a comparative law approach with respect to relational contract law and found that the relational features of the procurement systems analyzed could be implemented within a regulatory framework to counterbalance their transactional aspects in order to facilitate the implementation of more collaborative delivery methods (

Jobidon et al. 2018). Studies have thus mainly focused on the validity and pertinence of relational contract law in the context of long-term contractual relationships, as well as on the direction of future work in the field and the application of the theory to the procurement process. The fact that the actual content of construction and professional services contracts and the language used to form the parties’ obligations have not been specifically studied within the field of law contributes to the pertinence of this paper.

Economics scholars have also paid attention to the concept of relational contract law and especially to the incompleteness of long-term contracts (

MacNeil 1974a). In practice, contracts cannot foresee every possible contingency (

Grossman and Hart 1986;

Hart and Moore 1990;

Hart 1995). Hart defines an incomplete contract as one that “has gaps, missing provisions, and ambiguities and has to be completed (by renegotiation or by the courts)” (

Hart 1995). Hart researched this concept in the context of PPPs, privatization, and integration (

Hart 2003). Hart confirms that long-term contracts are not only effectively incomplete in practice but that they should be incomplete. He developed a model of incomplete contracting to analyze PPPs, suggesting that the choice between PPPs and conventional provisions depends on whether it is easier to write contracts on service provisions rather than on building provisions (

Hart 2003). The incompleteness of contracts has been attributed to the transaction costs associated with contracting for a given contingency, which are greater than the benefits of such formalization (

Ayres and Gertner 1989;

MacNeil 1978;

Williamson 1985). Transaction costs include the negotiation process and fees, drafting costs, legal fees, and researching of a contingency’s effects and probability, as well as the judicial fees associated with determining whether the contingency occurred (

Ayres and Gertner 1989). The notion of incomplete contracts is therefore similar to the theory of the firm because of the difficulties arising in foreseeing the uncertain future and the parties’ desire to minimize transaction costs (

Hart 2003;

Hart and Moore 2008), defined by Arrow as the costs of running the economic system (

Arrow 1969).

Moreover, incomplete contracts are considered to be the most cost-effective form of governance for long-term contracts (

Campbell and Harris 1993). Filling the gaps left in long-term contracts requires the use of flexibility and soft terms, which structure the exchange and its evolution, therefore enabling parties to minimize costs and save time in certain future disputes (

Nystén-Haarala et al. 2010;

Woolthuis et al. 2005). Of course, there are risks to the use of incomplete contracts and soft terms, such as opportunistic and narrow interpretation by parties in the event of a dispute, as well as parties not shifting their attitudes to more cooperative stances (

Campbell and Harris 1993). Transaction costs would not be of the greatest importance if parties had the opportunity to find easy contracting alternatives, but because a breakup is more often than not inefficient, parties are often faced with the hold-up problem (

Klein et al. 1978;

Williamson 1985). Specific investments of the ex-ante relationship increase the potential surplus generated by the long-term exchange, and most of these investments will be lost when the relationship is broken. When negotiating the sharing of the ex post surplus, ex-ante investments have already been made and therefore do not affect the bargaining outcome, which could lead parties to rely on the wrong investment incentives. Because the sharing of the ex post surplus cannot be fixed ex ante, renegotiation of the initial contract will therefore inevitably occur when the exchange surplus becomes clear (

Bös and Lülfesmann 1996). However, the classic hold-up problem has been developed in a private procurement or private buyer–private seller context (

Hart and Moore 1988;

Williamson 1985). In a public procurement setting, where public bodies seek to maximize social welfare and private firms wish to maximize profit, authors claim that the suppliers’ overall profit should be zero but not necessarily at every step of the procurement process. Negative economic profit should be earned in the procurement’s innovation phase, meaning the design phase of a building process, whereas positive profit should be earned in the realization phase (

Bös and Lülfesmann 1996;

Rogerson 1992). Soft budget constraints for public entities are considered necessary to enable renegotiation when the private contractor is not willing to complete the project because of an underestimated ex-ante trade price (

Bös and Lülfesmann 1996). A need for innovation—so important in the case of public procurement for ecofriendly buildings—should lead public entities to pay a price to enhance innovative practices (

Rogerson 1992).

Bridging the gap between the fields of economics and governance is Williamson’s work regarding transaction cost economics and the governance of contractual relations (

Williamson 1979). He identifies the critical factors that need to be accounted for while describing contractual relations or the type of transaction: uncertainty, frequency (recurrence of the transaction), and idiosyncrasy (the degree to which durable transaction-specific investments are incurred). The classification of the type of transaction is important because, depending on the type, transactions should be matched with the appropriate governance structure. Williamson describes idiosyncratic services as those in which investments of transaction-specific human and physical capital are made and gives the example of trades where delivery for a specialized design is extended over a long period of time, such as some construction contracts (

Williamson 1979). He, therefore, gives the example of the construction of a plant, which is considered to be an occasional, idiosyncratic transaction. Williamson then identifies three broad types of governance structures: non-transaction-specific, semi-specific, and highly specific. The prime example of a non-transaction-specific governance structure is the market, an impersonal structure for the exchange of standardized goods at an equilibrium price (

Ben-Porath 1980), whereas highly specific structures are bespoke to the transaction’s special exigencies. Williamson then relates these governance structures with Macneil’s distinction between classical, neoclassical, and relational contract law, adding that relational contracting is best-suited for recurrent and non-standardized transactions, whereas neoclassical contracting (or trilateral governance) is adapted for occasional, non-standardized transactions. This implies that public contracts for construction projects and professional services should, according to Williamson, be governed by a neoclassical structure. While recent approaches to governance applied to the broader field of global supply chains have nuanced Williamson’s three main governance structures to include a four-way classification of governance structures (

Gereffi 2014;

Locke 2013;

Salminen 2017), the more relevant field of procurement of complex performance has let go of Williamson’s neoclassical governance structure by continuously trying to oppose classical formal and relational governance, leaving the neoclassical intermediary relegated to an afterthought.

Governance research has recently addressed the question of procurement of complex performance as it pertains to relational contract theory (

Caldwell and Howard 2010;

Lewis and Roehrich 2009). Complexity is considered to be a mesh of different factors, covering the number of project stakeholders, the length of the planning negotiations, and the construction phase, as well as the presence of bespoke infrastructural components. It can be applied to IPD projects, which deal with organizational complexity in terms of horizontal differentiation, personal specialization, and reciprocal interdependencies, as well as with technological complexity, such as task interdependency created, for instance, by the utilization of BIM (

Baccarini 1996;

Mohr 1971;

Roehrich and Lewis 2014). Other forms of complexity specifically affect the procurement process for construction projects and professional services, mainly involving ex-ante transactional complexity, such as design and service specifications, as well as infrastructural complexity, such as financial and organizational structures (

Zheng et al. 2008). As discussed above, contractual and relational structures are the two main governance structures that have been proposed in the literature in recent years. While it seems odd to oppose the two usually intricate notions, governance literature diverges from law inasmuch as contractual governance loosely relates to discrete transactions and the predominant role of formal contracts to safeguard parties from opportunistic behavior (

Cao and Lumineau 2015). Relational governance more specifically relates to trust as an alternative to formal contracts and to presentiation to mitigate uncertain and transaction-specific investments (

Cao and Lumineau 2015;

Heide and John 1992;

MacNeil 1980a).

As is the case with many concepts, striking a balance between seemingly opposite poles seems to be the preferred option. The literature states that contractual and relational governance should be considered complementary mechanisms (

Cao and Lumineau 2015;

Ferguson et al. 2005;

Poppo and Zenger 2002). In complex procurement arrangements, an increase in relational exchange governance should help contractual exchange governance (

Roehrich and Lewis 2014) mainly by improving relationship performance, especially in a high uncertainty contractual relationship (

Cannon et al. 2000). Researchers have identified a correspondence principle between the complexity of projects and that of governance structures: the more complex the project, the more complex the governance structures, decision processes, and strategies should be (

Boisot and Child 1999;

Eisenhardt et al. 2000). The importance of trust in the procurement process is repeatedly emphasized in the governance field. Fostering interpersonal and inter-organizational trust through the iterative processes of bargaining, commitment, and joint activities between partners helps to establish feedback channels and develop team familiarity, which in turn can lead to increased project performance (

Ring and Van de Ven 1994;

Roehrich and Lewis 2014). Establishing trusting relationships during the more sensitive early stage of the procurement process was also found to help with the development of the relationship. This also helps parties resolve contractual issues arising in later project phases due to the incompleteness of long-term arrangements in a more flexible manner (

Roehrich and Lewis 2014). IPD projects are often tinged with complexity, whether organizational or technological, and are inherently uncertain because of the long-term nature of the arrangement and the myriad possible design outcomes. There is, therefore, a need to identify specific relational content or mechanisms that can complement the formal contractual public procurement process—one of the aims of the present paper.

The field of marketing has also contributed to relational contract theory by analyzing the applicability of Macneil’s norms in the context of a commercial exchange. The norms of solidarity, mutuality (reciprocity), flexibility, role integrity, restraint of power, conflict resolution (harmonization of conflict), and relationship focus (implementation of planning and effectuation of consent) were found to be operationalizable to analyze buyer–seller relationships (

Harper 2014;

Kaufmann and Dant 1992). Reciprocity, role integrity, and solidarity were also found to have an effect on the perception of unfair treatment by a party, which also affects the ex post retained level of hostility, thereby relating solidarity to the level of perceived fairness (

Harper 2014;

Kaufmann and Stern 1988). Other researchers have also confirmed the pertinence of using a transactional/relational continuum and have empirically observed that transactional and relational types of exchange can coexist at the supply chain level (

Lefaix-Durand and Kozak 2009). Furthermore, it was found that healthy business relationships are considered to be a major source of value creation and that a link between value creation in relationships and competitiveness exists (

Lefaix-Durand 2008).

Management scholars have also shown interest in Macneil’s relational contract law and application, especially in the concept of trust, or solidarity. Sake and Helper carried out a comparative study regarding the determinants of inter-organizational trust in supplier relations in Japan and the United States (US). They found significant differences between each country’s perception of written contracts. Contracts were considered to be irrelevant governance mechanisms in Japan, whereas the use of formal agreements and the length of past trading were correlated with greater opportunism in the US. The researchers also identified conditions facilitating the creation and sustenance of trust, such as long-term commitment, information exchange, technical assistance, and customer reputation (

Sako and Helper 1998). In earlier work, Sako also found that trust reduces transaction costs in relation to bargaining and monitoring, thus enhancing performance (

Sako 1991). Jeffries and Reed explored the effects of interaction between organizational and interpersonal trust on negotiators’ motivation to problem solve in a relational contract environment. Trust has almost always been perceived as good and as having positive effects on performance, but the authors propose a counter-intuitive conclusion by stating that there is a downside to trust, mainly in the form of reduced motivation for negotiators. They, therefore, demonstrate Granovetter’s paradox of trust: while trust facilitates the emergence of norms, such as expectations of proper behavior, it also reduces risk perception and enables abuse through opportunism (

Dyer and Singh 1998;

Granovetter 1985). However, Jeffries and Reed suggest that when organizations enter relational contracts in a low trust environment, negotiators should not change over a sufficiently long period of time to help develop affect-based trust (

Jeffries and Reed 2000).

Blomqvist et al. analyzed the roles of trust and contracts in the context of an asymmetric research and development (R/D) collaboration. First, they reiterate the quasi-impossibility and futility of trying to presentiate a long-term arrangement embedded in uncertainty by stating that a successful collaborative exchange cannot be guaranteed by a detailed contract. However, they do affirm that the contract and the contracting process have the potential to increase mutual understanding and learning, thereby building trust (

Blomqvist et al. 2005). This relates to the previously addressed vision of trust by governance scholars, who state that trust is a cyclical process of recurrent bargaining commitment and execution of events between partners—a notion somewhat similar to Zucker’s process-based or relational trust (

Zucker 1985). While earlier scholars thought that trust was either present or absent (

Hirshleifer 1983;

Raiffa 1957), Zucker confirmed that there exist trust-producing mechanisms whether from individuals, firms, or industries (

Zucker 1985). In the present paper, we adhere to this interpretation of trust-producing mechanisms and identify those mechanisms associated with different procurement delivery methods.

More specifically, the field of construction management is related to public construction contracts. Alsagoff and McDermott believe the industry’s fascination with relational contracting, long-term partnering, and collaborative contracting stems from “Japan manufacturing”-style contracting, notably the works of Asanuma (

Asanuma 1988), Ikeda (

Ikeda 1987), and Morris and Imrie (

Morris and Imrie 1993), which see relational contracting as a solution offering the benefits of vertical integration while still maintaining flexibility in competitive markets (

Alsagoff and McDermott 1994). The authors also note that major institutional research wishes to encourage healthy long-term relationships in the United Kingdom (UK)’s construction industry through the use of joint ventures and partnering (

Latham 1994). The famous Latham Report conveys relational attitudes, ideas, and principles, such as the fact that (1) good relationships based on mutual trust benefit clients, (2) the use of contractual documents should place the emphasis on teamwork and partnership to solve problems, and (3) there is a need for a general duty to trade fairly (

Latham 1994). Following the Latham Report, scholars have paid further attention to the concept of relational contracting in the field of construction. Cheung et al. discussed the application of relational contracts in construction by examining the relational level of construction contracts using a relational index based on eight factors: (1) cooperation, (2) organizational culture, (3) risk, (4) trust, (5) good faith, (6) flexibility, (7) the use of alternative dispute resolution, and (8) contract duration. Although their analysis was restricted to the context of the traditional design–bid–build (DBB) method, it was found that the main contract and domestic subcontract forms are more relational than those of the nominated subcontracts and the direct labor contract. The authors also note that a major prerequisite for fostering cooperation relies on maintaining a good relationship between the client and the main contractor. Because the client is the main source of work and revenue, the maintenance of a healthy long-term relationship is key for the survival of a main contractor. More importantly, the authors found that the concepts of relational contracting may not be applicable to every delivery method type, such as DBB. According to them, different contract types foster different characteristics, whether transactional or relational, and some delivery methods might be ill-suited to the use of relational contracting principles (

Cheung et al. 2006). This last point is of great importance to the theme of this paper, which will demonstrate the gap in relational content in the contractual language presented by different project delivery methods.

In a series of papers regarding relational contracting and the necessity of relationally integrated teams, Rahman and Kumaraswamy reiterate the need for appropriate contracting methods and documents coupled with the attitude of contracting parties and their cooperative relationship to ensure successful project delivery (

Rahman and Kumaraswamy 2002). They underline the necessity of joint and dynamic risk management and flexible contract conditions, allowing for quick adjustment by the parties to the inevitable problems that will arise and highlighting the advantages of joint risk management (

Rahman and Kumaraswamy 2002). In a subsequent paper regarding the need for relational integration, these researchers found four factors facilitating the team-building process: (1) the client’s competencies and overall learning/training policy; (2) previous interactions, performance, competencies, and specific input and outputs of various partners; (3) compatible organizational culture, longer-term focus, and emphasis on trust building; and (4) improved selection of project partners and better delegation of responsibilities (

Kumaraswamy et al. 2005). The factors deterring the team-building process are divided into five major components: (1) lack of trust, open communication, and uneven commitment; (2) commercial pressure, absent or unfair risk/reward planning, and incompatible personalities or organizational cultures; (3) lack of general top management commitment and client’s knowledge/initiative; (4) lack of good relationships among the team players; and (5) exclusion of some team players in risk/reward plans, errors, and cultural inertia (

Kumaraswamy et al. 2005). Although these components go beyond the frame of the present study, many of them can be related to contractual language and content, such as the presence or absence of trust-producing mechanisms (

Zucker 1985) and the risk sharing or risk allocation mechanisms laid out by the contract. In further research, Rahman and Kumaraswamy highlight the need for reviewing contractual conditions to accommodate relational contracting principles (

Bayliss 2002;

Motiar Rahman and Kumaraswamy 2005), such as using contractual incentives to persuade contractors to adopt relational contracting approaches (

Ling et al. 2006). Kumaraswamy et al. also note that relational contracting principles are more easily applied to private sector projects than public ones (

Kumaraswamy et al. 2010;

Ling et al. 2013a). They also point out that it is still not well known if public projects can fully benefit from relational contracting principles (

Dulaimi et al. 2007), because of the necessity of public clients to use the competitive bidding process, which does not put them in a position to offer incentives for future relationships. The mistrust of public clients developing business relationships with private providers—a fear embedded in the state’s desire to reduce corruption in construction—has also affected institutional trust and relational development in Quebec (

Jobidon et al. 2018). A recent study conducted by Ling et al investigated relational transactions and overall relationship quality by using common contractual norms of role integrity, flexibility, solidarity, propriety of means, and harmonization with the social matrix (

Ling et al. 2013b). Relationship quality between project partners can be predicted according to which relational practices are implemented, such as the adoption of flexible strategies, trust among team members, and the sharing of project information, just to name a few. Significant correlations between relationship quality and its impact on time performance and client satisfaction have been found, as is the case with high propriety of means, better cost performance, and client satisfaction (

Ling et al. 2013b).

One of the most recent studies focused on the construction of multiple-statement scales to measure relational norms—mainly the norms of role integrity, reciprocity, flexibility, propriety of means, reliance and expectations, restraint of power, contractual solidarity, and harmonization of conflict—in the context of construction projects (

Harper et al. 2016;

Harper 2014). The study essentially operationalized relational contracting norms to measure project integration in different construction contracts, although it mixed common contractual norms while leaving some behind, such as planning implementation with relational norms (harmonization of conflict). In his doctoral thesis, Harper found correlations between contractual norms and project success, while also concluding that IPD contracts present more relationally integrated teams than those of design–build, construction manager at risk, and design–bid–build delivery methods (

Harper 2014), thus confirming the previously stated fact by Matthews and Howell that IPD is an example of relational contracting (

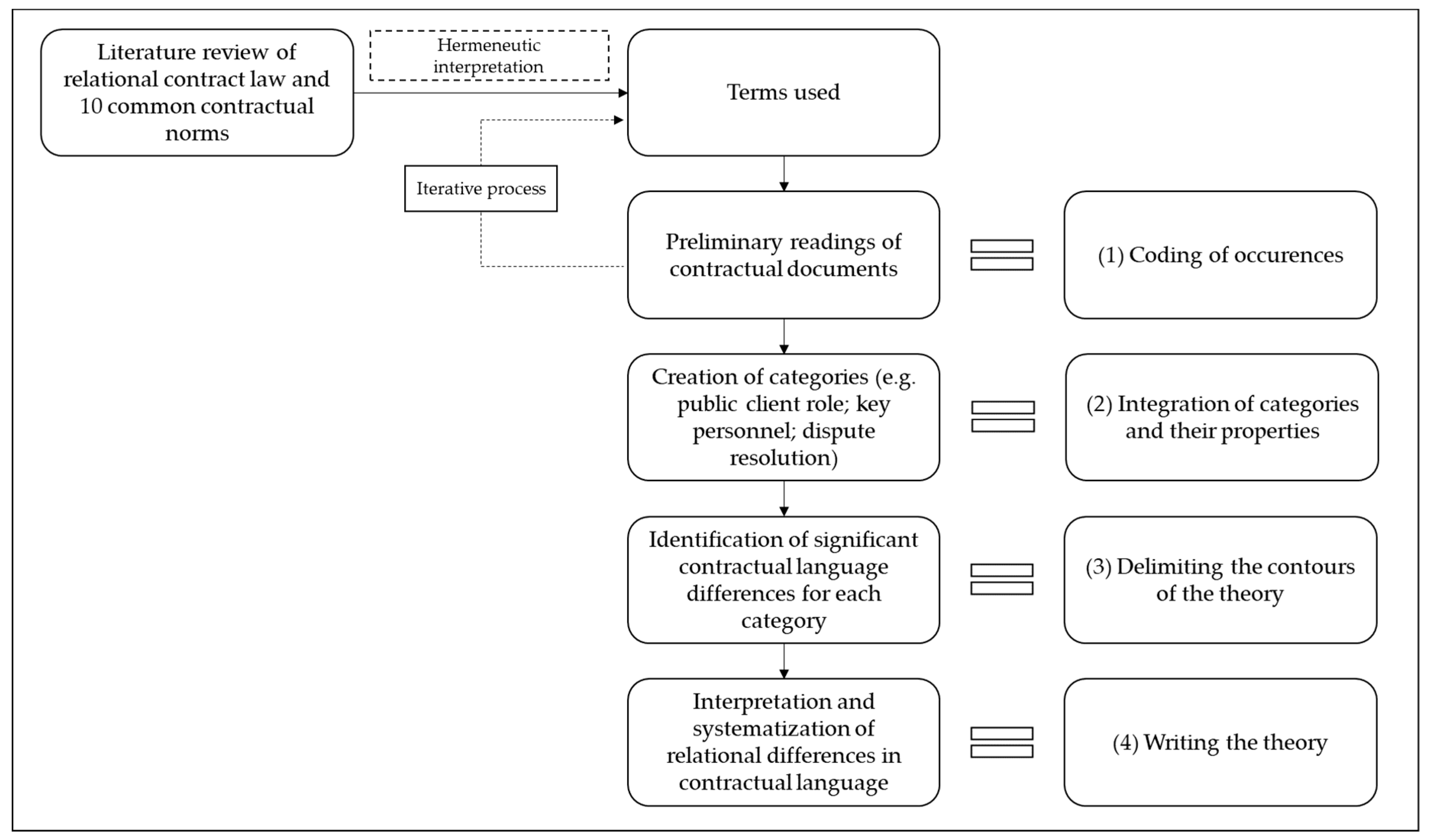

Matthews and Howell 2005). Although Harper analyzed the contractual language of different delivery methods, he did so by using occurrences, without specifying the main differences in the relational mechanisms provided for by different contracts or looking into the nature of the obligational content—elements that will be at the core of the present research.

This literature review of relational contract law, relational contracting principles, and their applications in different fields identifies the main gaps present in the literature, particularly pertaining to the application of relational contracts in the field of public contracts for construction projects and professional services in the context of vertical construction.

Table 1 below illustrates the key takeaways from this literature review.

Most of the studies cited focus on the validity and pertinence of relational contract law in the context of long-term relationships, the need for general relational contracting principles and their actual application during a project, the parties’ behavior in collaborative environments, and the need for both formal and informal processes to achieve project success. MacNeil emphasizes the element of planning in his work, and he assumes that relational contract law is useful for contract planning, which relates to the content of the contract and to the processes followed in the resulting relationship (

Diathesopoulos 2010). The present study will therefore shed light on the material differences between different public project delivery methods by analyzing the contractual language presented and the mechanisms provided for by the different contractual structures available to public clients in Quebec. In this paper, we will also identify what makes the content of a contract more or less relational and how different specific contractual mechanisms make a contract more or less relational, thus illustrating how a contract can serve as the foundation for the development of a healthy long-term relationship. The implementation of a relatively new contractual structure, such as IPD, which is tinged with organizational and technological complexity, creates the need for a better understanding of the different processes at hand for public entities wishing to enter long-term contractual relationships for the construction of vertical infrastructure.