A Word of Caution: Human Rights, Disability, and Implementation of the Post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. The CRPD and Sustainable Development

2.2. A Closer Look at the Formulation of the Post-2015 SDG Agenda

“[The MDGs] express targets that are feasible at the global level. They should not been seen as a normative statement of what is desirable in an ideal world, which is already embedded in the various human rights treaties that have been ratified by member state to varying degrees. There is no need to repeat or overlap with these instruments…”([32], p. 14)

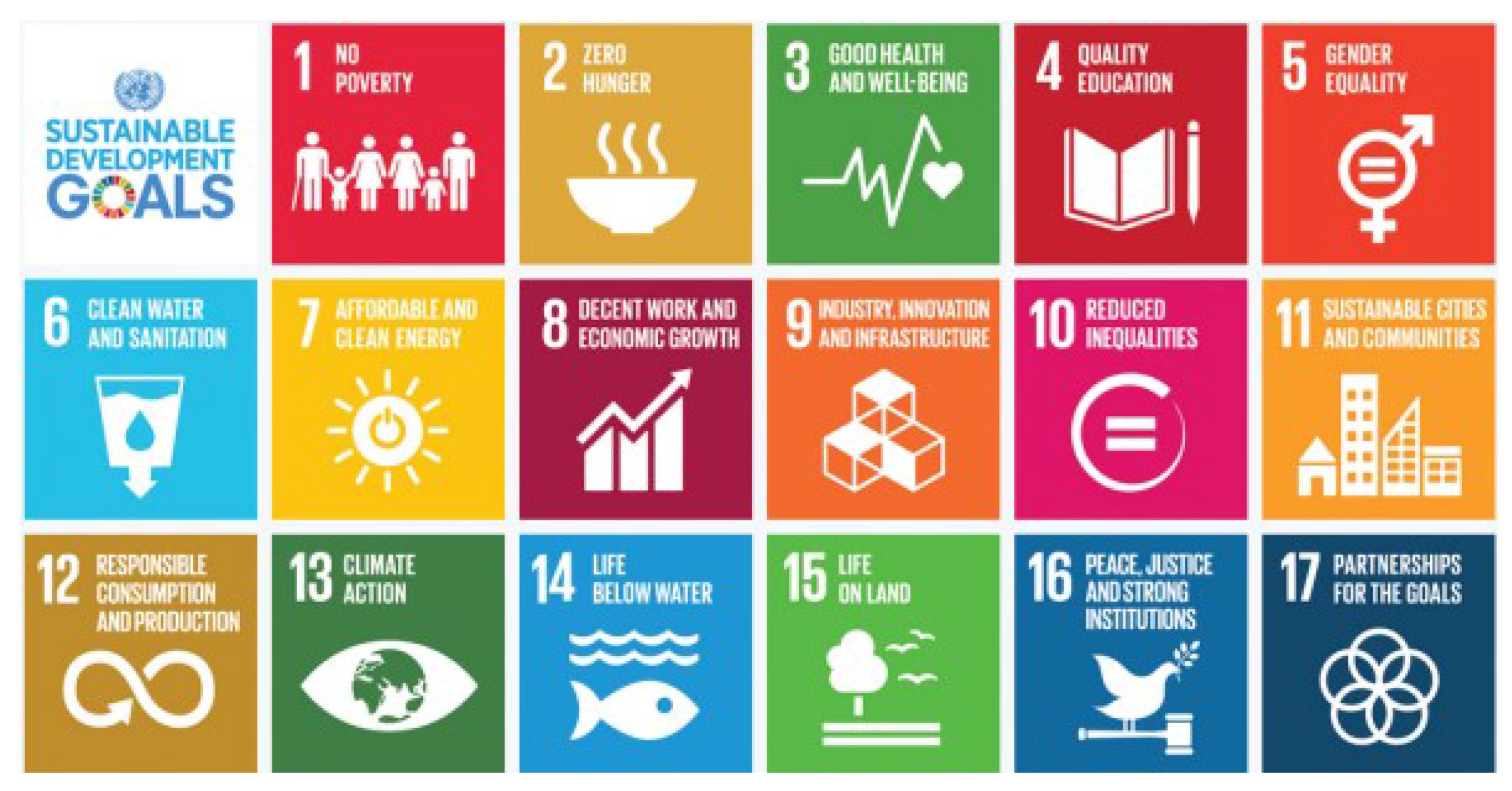

3. The Post-2015 SDGs Are an Advance on the MDG Agenda for Persons with Disabilities

3.1. The SDGs Are a Universal Agenda

“As we embark on this great collective journey, we pledge that no one will be left behind. Recognising that the dignity of the human person is fundamental, we wish to see the Goals and targets met for all nations and peoples and for all segments of society. And we will endeavour to reach the furthest behind first”([1], para. 4)

“This is an Agenda of unprecedented scope and significance. It is accepted by all countries and is applicable to all, taking into account different national realities, capacities and levels of development and respecting national policies and priorities. These are universal goals and targets which involve the entire world, developed and developing countries alike. They are integrated and indivisible and balance the three dimensions of sustainable development”([1], para. 5)

3.2. The SDGs Explicitly Embrace a Human Rights Agenda

“[The 17 SDGs and 169 targets are a]…new universal Agenda. They seek to build on the MDGs and complete what they did not achieve. They seek to realise the human rights of all…”[emphasis added] ([1], p. 1, preamble)

“Guided by the purposes and principles of the Charter of the UN, including full respect for international law. It is grounded in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, international human rights treaties, the Millennium Declaration and the 2005 World Summit Outcome. It is informed by other instruments such as the Declaration of the Right to Development”[emphasis added] ([1], para. 10)

“We reaffirm the importance of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, as well as other international instruments relating to human rights and international law. We emphasize the responsibilities of all States, in conformity with the Charter of the UNs, to respect, protect and promote human rights and fundamental freedoms for all, without distinction of any kind as to race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth, disability or other status”[emphasis added] ([1], para. 19)

3.3. The SDGs Expressly Include Persons with Disabilities

“People who are vulnerable must be empowered. Those whose needs are reflected in the Agenda include all children, youth, persons with disabilities (of whom more than 80 per cent live in poverty), people living with HIV/AIDS, older persons, indigenous peoples, refugees and internally displaced persons and migrants”[emphasis added] ([1], para. 23)

4. Three Steps Forward, But Four Steps Back

4.1. The UN Resolution on the Post-2015 SDGs Is a High-Level Policy Document Only, It Is Not Binding Instrument of International Law

4.2. As a High-Level Policy Document without Legal Standing, Its Accountability Mechanisms Are Flimsy

4.3. What Matters Is What Governments Will Prioritise for SDG Implementation: The 17 Goals, Their Targets and Means of Implementation, and Inter-Linked Country Indicators

4.4. The SDG Metrics Framework Does Not Sufficiently Identify and Include Persons with Disabilities

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRPD | Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities |

| MDG | Millennium Development Goal |

| NGOs | Non-government organisations |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| UN | United Nations |

| UNDG | UN Development Group |

References

- UN General Assembly. “Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.” 2015. Available online: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- UN General Assembly. “Road Map towards the Implementation of the UN Millennium Declaration: Report of the Secretary-General.” 6 September 2001. Available online: http://www.un.org/documents/ga/docs/56/a56326.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- Gorik Ooms, Claire Brolan, Natalie Eggermont, Asbjørn Eide, Walter Flores, Lisa Forman, Eric A. Friedman, Thomas Gebauer, Lawrence O. Gostin, Peter S. Hill, and et al. “Universal health coverage anchored in the right to health.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 91 (2013): 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peter S. Hill, Kent Buse, Claire E. Brolan, and Gorik Ooms. “How can health remain central post-2015 in a sustainable development paradigm? ” Globalization and Health 10 (2014): 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claire E. Brolan, and Peter S. Hill. “Countdown for health to the post-2015 UN Sustainable Development Goals.” Medical Journal of Australia 202 (2015): 289–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moses Mulumba, Juliana Nantaba, Claire E. Brolan, Ana Lorena Ruano, Katie Brooker, and Rachel Hammonds. “Perceptions and experiences of access to public healthcare by people with disabilities and older people in Uganda.” International Journal for Equity in Health 13 (2014): 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo Durham, Claire E. Brolan, and Bryan Mukandi. “The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: A foundation for ethical disability and health research in developing countries.” American Journal of Public Health 104 (2014): 2037–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anh D. Ngo, Claire Brolan, Lisa Fitzgerald, Van Pham, and Ha Phan. “Voices from Vietnam: Experiences of children and youth with disabilities, and their families, from an Agent Orange affected rural region.” Disability and Society 28 (2012): 955–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claire E. Brolan, K. Van Dooren, M. Taylor Gomez, Robert S. Ware, and Nicholas G. Lennox. “Suranho healing: Filipino concepts of intellectual disability and treatment choices in Negros Occidental.” Disability and Society 29 (2013): 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claire E. Brolan, M. Taylor Gomez, Nicholas G. Lennox, and Robert S. Ware. “Australians from a non-English speaking background with intellectual disability: The importance of research.” Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability 38 (2013): 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN General Assembly. “Resolution adopted by the General Assembly. United Nations Millennium Declaration.” 18 September 2000. Available online: http://www.un.org/millennium/declaration/ares552e.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- United Nations. “Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Adopted 13 December 2016, GA Res 61/106, UN Doc A/Res/61/106, Entered into Force 3 May 2008.” Available online: http://www.un.org/disabilities/convention/conventionfull.shtml (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- Paul Harpur. “Embracing the new disability rights paradigm: The importance of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.” Disability and Society 27 (2012): 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart W. Mercer, and Rhona MacDonald. “Disability and human rights.” The Lancet 370 (2007): 548–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neha Bhat. “Mainstreaming Disability in International Development: A Review of Article 32 on International Co-Operation on the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.” 6 May 2013. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2262946 (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- Alana Officer, and Nora E. Groce. “Key concepts in disability.” The Lancet 374 (2009): 1795–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria Kett, and Mark van Ommeren. “Disability, conflict, and emergencies.” The Lancet 374 (2009): 1801–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, and the World Bank. “World Report on Disability.” 2011. Available online: http://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/en/ (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- World Health Organization. “Disability and Health (Factsheet No. 352).” December 2015. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs352/en/ (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- UN Development Group (UNDG). “Developing the Post-2015 Development Agenda: Opportunities at the National and Local Levels.” 2014. Available online: http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/MDG/Post2015-SDG/UNDP-MDG-Delivering-Post-2015-Report-2014.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- Beyond2015. “UN Thematic Consultations.” 2015. Available online: http://www.beyond2015.org/un-thematic-consultations (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- International Disability Alliance, and the International Disability and Development Consortium. “Include Persons with Disabilities in the Sustainable Development Process.” Available online: http://iddcconsortium.net/sites/default/files/pages/files/ida_and_iddc_owg_statement.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- World Health Organization. “UN High-Level Meeting on Disability and Development.” 2016. Available online: http://www.who.int/disabilities/hlm/en/ (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- UN General Assembly. “Outcome Document of the High-Level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Realization of the Millennium Development Goals and Other Internationally Agreed Development Goals for Persons with Disabilities: The Way Forward, a Disability-Inclusive Development Agenda towards 2015 and Beyond.” September 2013. Available online: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/68/L.1 (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- Nora E. Groce, and Jean-Francois Trani. “Millennium Development Goals and people with disabilities.” The Lancet 374 (2009): 1800–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan Vandemoortele. “Making sense of the MDGs.” Development 51 (2008): 220–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael W. Doyle. “Dialectics of a global constitution: The struggle over the UN Charter.” European Journal of International Relations 18 (2011): 601–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mac Darrow. “The Millennium Development Goals: Milestones or Millstones? Human Rights Priorities for the Post-2015 Development Agenda.” Yale Human Rights and Development Law Journal 15 (2012): 55–127. [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm Langford. “The Art of the Impossible: Measurement Choices and the Post-2015 Development Agenda (Background Paper Governance and Human Rights: Criteria and Measurement Proposals for a Post-2015 Development Agenda).” 2012. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/776langford.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- Jan Vandemoortele. “The MDG Conundrum: Meeting the Targets without Missing the Point.” Development Policy Review 27 (2009): 355–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John McArthur. “Own the Goals: What the Millennium Development Goals Have Accomplished.” Brookings. 21 February 2013. Available online: http://www.brookings.edu/research/articles/2013/02/21-millennium-dev-goals-mcarthur (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- Jan Vandemoortele. “If not the Millennium Development Goals, then What? ” Third World Quarterly 32 (2011): 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David Hulme. “Governing global Poverty? Global ambivalence and the Millennium Development Goals.” In Governance, Poverty and Inequality. Edited by Jennifer Clapp and Rorden Wilkinson. London and New York: Routledge, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sakiko Fukuda-Parr. “Recapturing the narrative of international development.” In The Millennium Development Goals and Beyond. Edited by Rorden Wilkinson and David Hulme. Milton Park: Routledge, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Claire E. Brolan, Robert S. Ware, Miriam Taylro Gomez, and Nicholas G. Lennox. “The right to health of Australians with intellectual disability.” Australian Journal of Human Rights 17 (2011): 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Claire E. Brolan, Sameera Hussain, Eric A. Friedman, Ana Lorena Ruano, Moses Mulumba, Itai Rusike, Claudia Beiersmann, and Peter S. Hill. “Community participation in formulating the post-2015 health and development goal agenda: Reflections on a multi-country research collaboration.” International Journal for Equity in Health 13 (2014): 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. “The Millennium Development Goals Report 2015.” Available online: http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2015_MDG_Report/pdf/MDG%202015%20rev%20%28July%201%29.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- Rahul Chandran, Hannah Cooper, and Alexandra Ivanovic. “Managing Major Risks to Sustainable Development: Conflict, Disaster, the SDGs and the United Nations: A Report Prepared for the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs for the 2016 Quadrennial Comprehensive Policy Review.” 17 December 2015. Available online: http://www.un.org/en/ecosoc/qcpr/pdf/sgr2016-deskreview-transition.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- UNDP. “Helen Clark: Speech on 2030 Agenda and the SDGs in Fragile States.” 3 March 2016. Available online: http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/presscenter/speeches/2016/03/03/helen-clark-2030-agenda-and-the-sdgs-in-fragile-states-european-parliament.html (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- Andy Sumner. “The New Bottom Billion: What if Most of the World’s Poor Live in Middle-Income Countries? Center for Global Development (CGD Brief).” March 2011. Available online: http://www.cgdev.org/files/1424922_file_Sumner_brief_MIC_poor_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- Paul Lucas, Norichika Kanie, and Nina Weitz. “Translating the SDGs to High-Income Countries: Integration at Last? IISD Reporting Services.” 17 March 2016. Available online: http://sd.iisd.org/guest-articles/translating-the-sdgs-to-high-income-countries-integration-at-last/ (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- United Nations. “Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action: Adopted by the World Conference on Human Rights on 25 June 1993, UN Doc A/CONF.157/23.” Available online: http://www.un-documents.net/ac157-23.htm (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- United Nations. “Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties Concluded at Vienna on 23 May 1969. Entered into Force on 27 January 1980.” Available online: https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%201155/volume-1155-I-18232-English.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- International Court of Justice. “Statute of the International Court of Justice (Annexed to the Charter of the United Nations).” Available online: http://www.icj-cij.org/documents/?p1=4&p2=2#CHAPTER_II (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- Andre Da Rocha Ferreira, Cristieli Carvalho, Fernanda Graeff Machry, and Pedro Barreto Vianna Rigon. “Formation and Evidence of Customary International Law.” UFRGS Model United Nations Journal 1 (2013): 182–201. [Google Scholar]

- International Law Association. London Statement of Principles Relating to the Formation of General Customary International Law. London: International Law Association, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm N. Shaw. International Law, 4th ed. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Claire E. Brolan, Peter S. Hill, and Gorik Ooms. “‘Everywhere but not specifically somewhere’: A qualitative study on why the right to health is not explicit in the post-2015 negotiations.” BMC International Health and Human Rights 15 (2015): 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. “High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development.” Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/hlpf (accessed on 11 May 2016).

- United Nations. “Millennium Goal 8 the Global Partnership for Development: Making Rhetoric a Reality.” Available online: http://www.who.int/medicines/mdg/mdg8report2012_en.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- Charles Kenny, and Sarah Dykstra. “The Global Partnership for Development: A Review of MDG 8 and Proposals for the Post-2015 Development Agenda (Background Research Paper).” Submitted to the High Level Panel on the Post-2015 Development Agenda. May 2013. Available online: http://www.post2015hlp.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Kenny-Dykstra_The-Global-Partnership-for-Development-Proposals-for-the-Post-2015-Development-Agenda.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- Aldo Caliari. “Analysis of Millennium Development Goal 8: A Global Partnership for Development.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 15 (2014): 275–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakiko Fukuda-Parr. “Millennium Development Goal 8: Indicators for International Human Rights Obligations? ” Human Rights Quarterly 28 (2006): 966–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip Alston. “Ships Passing in the Night: The Current State of the Human Rights and Development Debate seen through the Lens of the Millennium Development Goals.” Human Rights Quarterly 27 (2005): 755–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaine Unterhalter. “Measuring Education for the Millennium Development Goals: Reflections on Targets, Indicators, and a Post-2015 Framework.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 15 (2014): 176–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claire E. Brolan, Peter S. Hill, and Ignacio Correa-Velez. “Refugees: The Millennium Development Goals’ Overlooked Priority Group.” Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies 10 (2012): 426–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claire E. Brolan, Stephanie Dagron, Lisa Forman, Rachel Hammonds, Lyla Latif Abdul, and Attiya Waris. “Health rights in the post-2015 development agenda: Including non-nations.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 91 (2013): 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF. “Expanding Millennium Development Goal 5: Universal Access to Reproductive Health by 2015.” Available online: http://www.unicef.org/sowc09/docs/SOWC09-Panel-1.4-EN.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (Ministry of Economy). “Afghanistan Millennium Development Goals Report 2012.” Available online: http://www.af.undp.org/content/dam/afghanistan/docs/MDGs/Afghanistan%20MDGs%202012%20Report.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2016).

- Eve de La Mothe, Jessica Espey, and Guido Schmidt-Traub. “GSDR 2015 Brief. Measuring Progress on the SDGs: Multi-level Reporting.” Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/6464102-Measuring%20Progress%20on%20the%20SDGs%20%20%20Multi-level%20Reporting.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2016).

- 1I note that subsequent to writing this article, and such is the dynamic nature of the entire SDG process, a High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (the “HLPF”) has been advertised by the UN as the planned “central platform for the follow-up and review of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the SDGs” [49]. As to whether the HLPF will be duly respected by the UN Member States (and their development partners), and duly funded, so as to become an effective overarching accountability mechanism remains to be seen.

| Thematic Consultation Number | Issue Focus |

|---|---|

| 1 | Conflict, Violence and Disaster |

| 2 | Water |

| 3 | Education |

| 4 | Energy |

| 5 | Environmental Sustainability |

| 6 | Food Security and Nutrition |

| 7 | Governance |

| 8 | Growth and Employment |

| 9 | Health |

| 10 | Addressing Inequalities |

| 11 | Population Dynamics |

| SDG | Metric | Target Aim |

|---|---|---|

| Goal 4: Quality Education | Goal 4, Target 5 | 4.5 By 2030, eliminate gender disparities in education and ensure equal access to all levels of education and vocational training for the vulnerable, including persons with disabilities, indigenous peoples and children in vulnerable situations |

| Goal 8: Decent work and economic growth | Goal 8, Target 5 | 8.5 By 2030, achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value |

| Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities | Goal 11, Target 2 | 11.2 By 2030, provide access to safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable transport systems for all, improving road safety, notably by expanding public transport, with special attention to the needs of those in vulnerable situations, women, children, persons with disabilities and older persons |

| Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities | Goal 11, Target 7 | By 2030, provide universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible, green and public spaces, in particular for women and children, older persons and persons with disabilities |

| Finance | SDG-Target Detail |

| 17.1 | Strengthen domestic resource mobilization, including through international support to developing countries, to improve domestic capacity for tax and other revenue collection |

| 17.2 | Developed countries to implement fully their official development assistance commitments, including the commitment by many developed countries to achieve the target of 0.7 per cent of gross national income for official development assistance (ODA/GNI) to developing countries and 0.15 to 0.20 per cent of ODA/GNI to least developed countries; ODA providers are encouraged to consider setting a target to provide at least 0.20 per cent of ODA/GNI to least developed countries |

| 17.3 | Mobilize additional financial resources for developing countries from multiple sources |

| 17.4 | Assist developing countries in attaining long-term debt sustainability through coordinated policies aimed at fostering debt financing, debt relief and debt restructuring, as appropriate, and address the external debt of highly indebted poor countries to reduce debt distress |

| 17.5 | Adopt and implement investment promotion regimes for least developed countries |

| Technology | |

| 17.6 | Enhance North-South, South-South and triangular regional and international cooperation on and access to science, technology and innovation and enhance knowledge sharing on mutually agreed terms, including through improved coordination among existing mechanisms, in particular at the United Nations level, and through a global technology facilitation mechanism |

| 17.7 | Promote the development, transfer, dissemination and diffusion of environmentally sound technologies to developing countries on favourable terms, including on concessional and preferential terms, as mutually agreed. |

| 17.8 | 17.8 Fully operationalize the technology bank and science, technology and innovation capacity-building mechanism for least developed countries by 2017 and enhance the use of enabling technology, in particular information and communications technology |

| Capacity-Building | |

| 17.9 | Enhance international support for implementing effective and targeted capacity-building in developing countries to support national plans to implement all the Sustainable Development Goals, including through North-South, South-South and triangular cooperation |

| Trade | |

| 17.10 | Promote a universal, rules-based, open, non-discriminatory and equitable multilateral trading system under the World Trade Organization, including through the conclusion of negotiations under its Doha Development Agenda |

| 17.11 | Significantly increase the exports of developing countries, in particular with a view to doubling the least developed countries’ share of global exports by 2020 |

| 17.12 | Realize timely implementation of duty-free and quota-free market access on a lasting basis for all least developed countries, consistent with World Trade Organization decisions, including by ensuring that preferential rules of origin applicable to imports from least developed countries are transparent and simple, and contribute to facilitating market access |

| Systemic Issues | Policy and institutional coherence |

| 17.13 | Enhance global macroeconomic stability, including through policy coordination and policy coherence |

| 17.14 | Enhance policy coherence for sustainable development |

| 17.15 | Respect each country’s policy space and leadership to establish and implement policies for poverty eradication and sustainable development |

| Multi-stakeholder partnerships | |

| 17.16 | Enhance the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development, complemented by multi-stakeholder partnerships that mobilize and share knowledge, expertise, technology and financial resources, to support the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals in all countries, in particular developing countries |

| 17.17 | Encourage and promote effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships, building on the experience and resourcing strategies of partnerships |

| Data, monitoring and accountability | |

| 17.18 | By 2020, enhance capacity-building support to developing countries, including for least developed countries and small island developing States, to increase significantly the availability of high-quality, timely and reliable data disaggregated by income, gender, age, race, ethnicity, migratory status, disability, geographic location and other characteristics relevant in national contexts |

| 17.19 | By 2030, build on existing initiatives to develop measurements of progress on sustainable development that complement gross domestic product, and support statistical capacity-building in developing countries |

| 8.A | Develop further an open, rule-based, predictable, non-discriminatory trading and financial system Includes a commitment to good governance, development and poverty reduction—both nationally and internationally |

| 8.B | Address the special needs of the least developed countries Includes tariff and quota free access for the least developed countries’ exports; enhanced programme of debt relief for heavily indebted poor countries (HIPC) and cancellation of official bilateral debt; and more generous ODA for countries committed to poverty reduction |

| 8.C | Address the special needs of landlocked developing countries and small island developing States (through the Programme of Action for the Sustainable Development of Small Island Developing States and the outcome of the twenty-second special session of the General Assembly) |

| 8.D | Deal comprehensively with the debt problems of developing countries through national and international measures in order to make debt sustainable in the long term |

| 8.E | In cooperation with pharmaceutical companies, provide access to affordable essential drugs in developing countries |

| 8.F | In cooperation with the private sector, make available the benefits of new technologies, especially information and communications |

| Post-2015 Goal | Target | Means of Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Goal 1: End poverty in all its forms everywhere | 1.4: By 2030, ensure that all men and women, in particular the poor and the vulnerable, have equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to basic services, ownership and control over land and other forms of property, inheritance, natural resources, appropriate new technology and financial services, including microfinance. | |

| Goal 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages | 3.b Support the research and development of vaccines and medicines for the communicable and non-communicable diseases that primarily affect developing countries, provide access to affordable essential medicines and vaccines, in accordance with the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health, which affirms the right of developing countries to use to the full the provisions in the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights regarding flexibilities to protect public health, and, in particular, provide access to medicines. | |

| Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all | 4.7: By 2030, ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development. | |

| Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls | 5.6: Ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights as agreed in accordance with the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development and the Beijing Platform for Action and the outcome documents of their review conferences. | 5.a: Undertake reforms to give women equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to ownership and control over land and other forms of property, financial services, inheritance and natural resources, in accordance with national laws. |

| Goal 8: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all | 8.8: Protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers in particular women migrants, and those in precarious employment. |

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brolan, C.E. A Word of Caution: Human Rights, Disability, and Implementation of the Post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals. Laws 2016, 5, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws5020022

Brolan CE. A Word of Caution: Human Rights, Disability, and Implementation of the Post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals. Laws. 2016; 5(2):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws5020022

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrolan, Claire E. 2016. "A Word of Caution: Human Rights, Disability, and Implementation of the Post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals" Laws 5, no. 2: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws5020022

APA StyleBrolan, C. E. (2016). A Word of Caution: Human Rights, Disability, and Implementation of the Post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals. Laws, 5(2), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws5020022