Immigration Federalism as Ideology: Lessons from the States

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Instrumental and Expressive Faces of Immigration Federalism

3. Immigration and Federalism in the Courts

States, Immigration and Consolidation of a National Regime

The demand for immigrants was most widespread and intense outside the densely populated states of the Northeast; in the West and South, virtually every state appointed agents or boards of immigration to lure new settlers from overseas. Michigan began the practice in 1845. By the end of the Civil War the northwestern states were competing with each other for Europeans to people their vacant lands and develop their economies. The South joined in, hoping to divert part of the current in its direction in order to restore shattered commonwealths and replace emancipated Negroes. In the 1860’s and 1870’s, at least twenty-five out of thirty-eight states took official action to promote immigration. South Carolina, in its desperation, added the inducement of a five-year tax exemption on all real estate bought by immigrants.([45], pp. 17–18)

Though it be conceded that there is a class of legislation which may affect commerce, both with foreign nations and between the states, in regard to which the laws of the states may be valid in the absence of action under the authority of Congress on the same subjects, this can have no reference to matters which are in their nature national or which admit of a uniform system or plan of regulation.([47], p. 260)

…a statute…framed, to place in the hands of a single man the power to prevent entirely vessels engaged in a foreign trade, say with China, from carrying passengers, or to compel them to submit to systematic extortion of the grossest kind.([48], p. 278)

4. Immigration Federalism in the Contemporary Era

4.1. State Lawmaking: An Overview

| Policy Areas | Bill Totals by Area | Percent Resolutions |

|---|---|---|

| Celebrate state’s immigrant heritage | 365 | 98% (357) |

| Border control & “comprehensive reform” | 32 | 88% (28) |

| Private bills, etc. | 372 | 85% (315) |

| Legal services for immigrants | 30 | 63% (19) |

| Education | 161 | 13% (21) |

| Employment | 200 | 13% (25) |

| Law enforcement | 225 | 11% (24) |

| Omnibus bills | 19 | 11% (2) |

| Human trafficking | 97 | 10% (10) |

| Health & health care | 121 | 10% (12) |

| Public benefits | 137 | 9% (13) |

| Voting and elections | 32 | 9% (3) |

| ID/Driver’s licenses, other licenses | 299 | 7% (20) |

| State budgets/appropriations relating to immigration or related agencies | 167 | 1% (2) |

| Policy Area | No. Laws | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | ID/driver’s licenses/other licenses | 279 |

| 2. | Law enforcement | 201 |

| 3. | Employment | 175 |

| 4. | State budgets/appropriations relating to immigration or related agencies | 165 |

| 5. | Education | 140 |

| 6. | Public benefits | 124 |

| 7. | Health & health care | 109 |

| 8. | Human trafficking | 87 |

| 9. | Private bills, etc. | 57 |

| 10. | Voting and elections | 29 |

| 11. | Omnibus bills | 17 |

| 12. | Legal services/assistance | 11 |

| 13. | Celebrate state’s immigrant heritage | 8 |

| 14. | Border control | 4 |

| Total Laws | 1406 | |

4.1.1. Identification and Licensing

| ID/Driver’s License Bills | Other State License Bills | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Allows ID/ Driver’s irrespective of immigration status | 8 | Professional Licensing | 63 |

| ID theft/fraud | 16 | Other Requirements (fees, expiration dates) | 49 |

| Anti-REAL ID | 28 | Gun permits/licensing | 34 |

| Regulations Consistent with REAL ID | 51 | Regulatory Business/Operating | 32 |

| Recreational licensing (hunting, fishing, etc.) | 16 | ||

| Birth certificates (overseas adoptions) | 3 | ||

| Subtotal | 103 | Subtotal | 197 |

4.1.2. Law Enforcement

| Type of Immigration Enforcement Law | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NJ | AZ (2) * MI, NY, TN (2) | MS | AZ (2) | AZ | SC | ||

| GA **, OH, IL (2), VA | AZ (2) AZ CO | AL, GA, IL, VA | CA, LA,SC | AZ (3), CA (2, 1 vetoed), CO, TX | DE | OK | |

| OH | NY, IL, TX | NC | AR, NH, OK | AZ | WA | DC, IL, PA | |

| GA, OH | NC | GA, VA | AZ, LA, OK | ||||

| CO, GA, OH | OK, TN | CO | CA (vetoed) TN, UT | GA, VA | AZ, MN (vetoed) TX, VA | AL | |

| GA | AZ, OK | MT (vetoed) | IN | ||||

| CO, SD | ME, OK, TN | CA, HI, UT, TN, CA | IA, TN, UT, AL | AL, CT, UT, MD, TN, KS | CA, ND, CT, UT, MI, MS, NM, OK, SD | KS, ME, UT | CO, MI, NM, |

| PA | DE, FL, LA | ||||||

| OK | TX |

4.1.3. Employment Laws

| Type of Employment Law | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Mandates BasicPilot/e-Verify…* | CO, PA, TN, GA | AZ, GA, IA, MI, TN, CO, GA, OKT, PA | CO, ID, AZ MS, AZ, SC * UT | GA, UT, VA | LA, TN, VA (2) | LA, PA, WV | GA, MO | |

| 2. Verification of work eligibility (without mandate for Basic Pilot/E-Verify)… | TX, HI, IA, WV | VA (3), TN, WV | IL, UT | FL, NE (2) | NC | |||

| 3. Workplace regulation, employment taxes, civil rights protections… | ID, WA, GA | AR, AZ, GA, IL | AZ, CO, FL | CA, IA, SC, VA, WA | CA, UT, VA | CT, CA | ||

| 4. Proof of legal status required to collect unemployment insurance or workman’s compensation.... | ID, KS, WA | HI, CO, IL, KS, LA, MN, MS, MT, NM, OR, UT, ME | AK | |||||

| 5. Penalties for employer violations of state eligibility laws… | LA, GA,CO | AZ, TN, WV, OKb | AZ, CO, MD, MO, MS, VA | HI, TN | HI, KS, ME, WV, WI | LA | MA, VA, TN | |

| 6. Penalties for immigrants falsifying work eligibility… | TN (2) | ID | NH | |||||

| 7. Restricts unemployment and/or workman’s comp, job training based on legal status... | MN, IA, IL | MS, NE, OK | MI, MIS, MO, NJ (vetoed), OR, UT, WA | AL | TN | |||

| 8. State limits or bans employer participation in BasicPilot/ E-Verify | IL (Ban) | CA (Bans unless federal funding at stake) |

4.1.4. Other Policy Areas

4.2. Immigration Federalism 2006–2013: A Reassessment

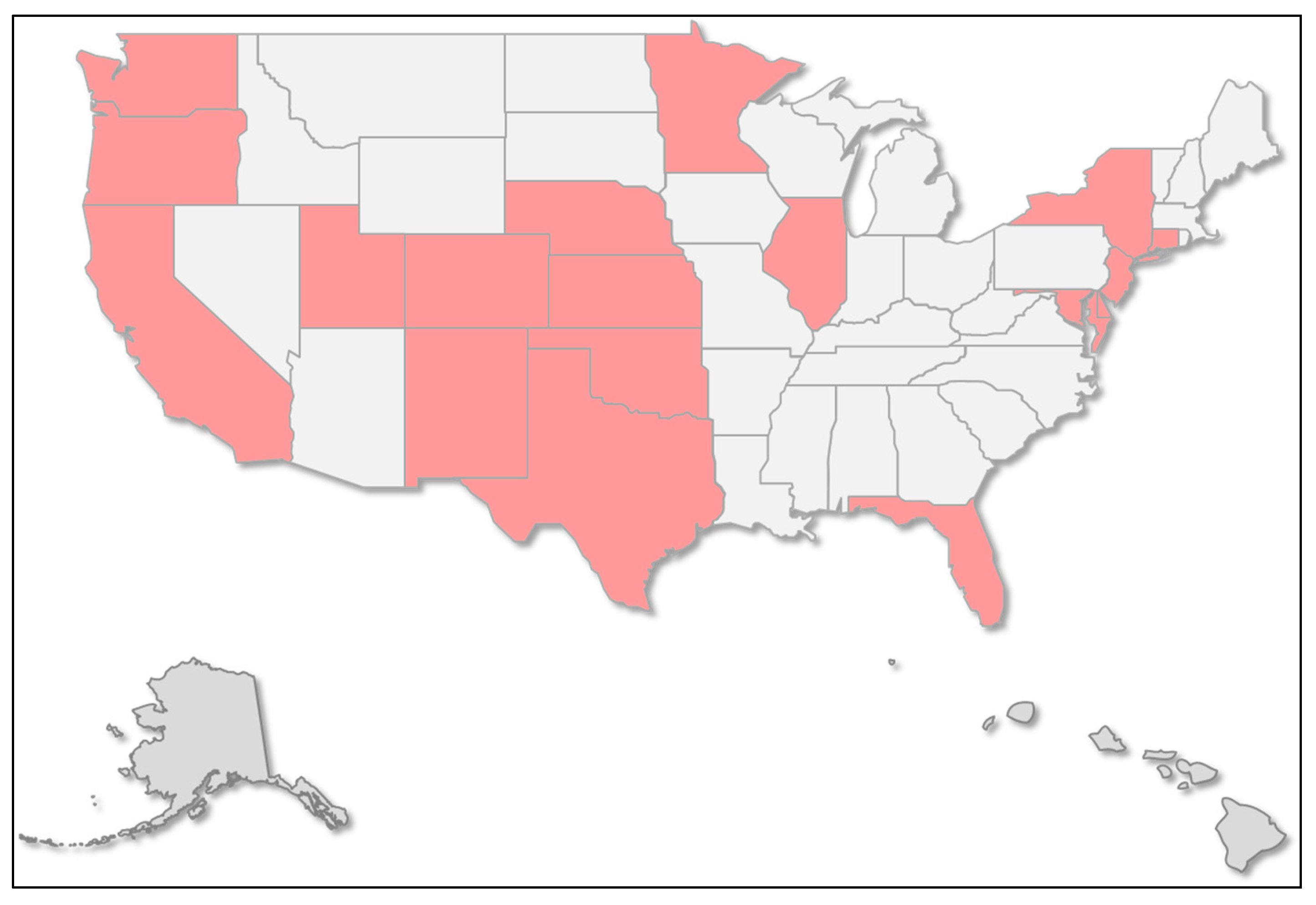

4.2.1. Higher Education Access for Undocumented Immigrants

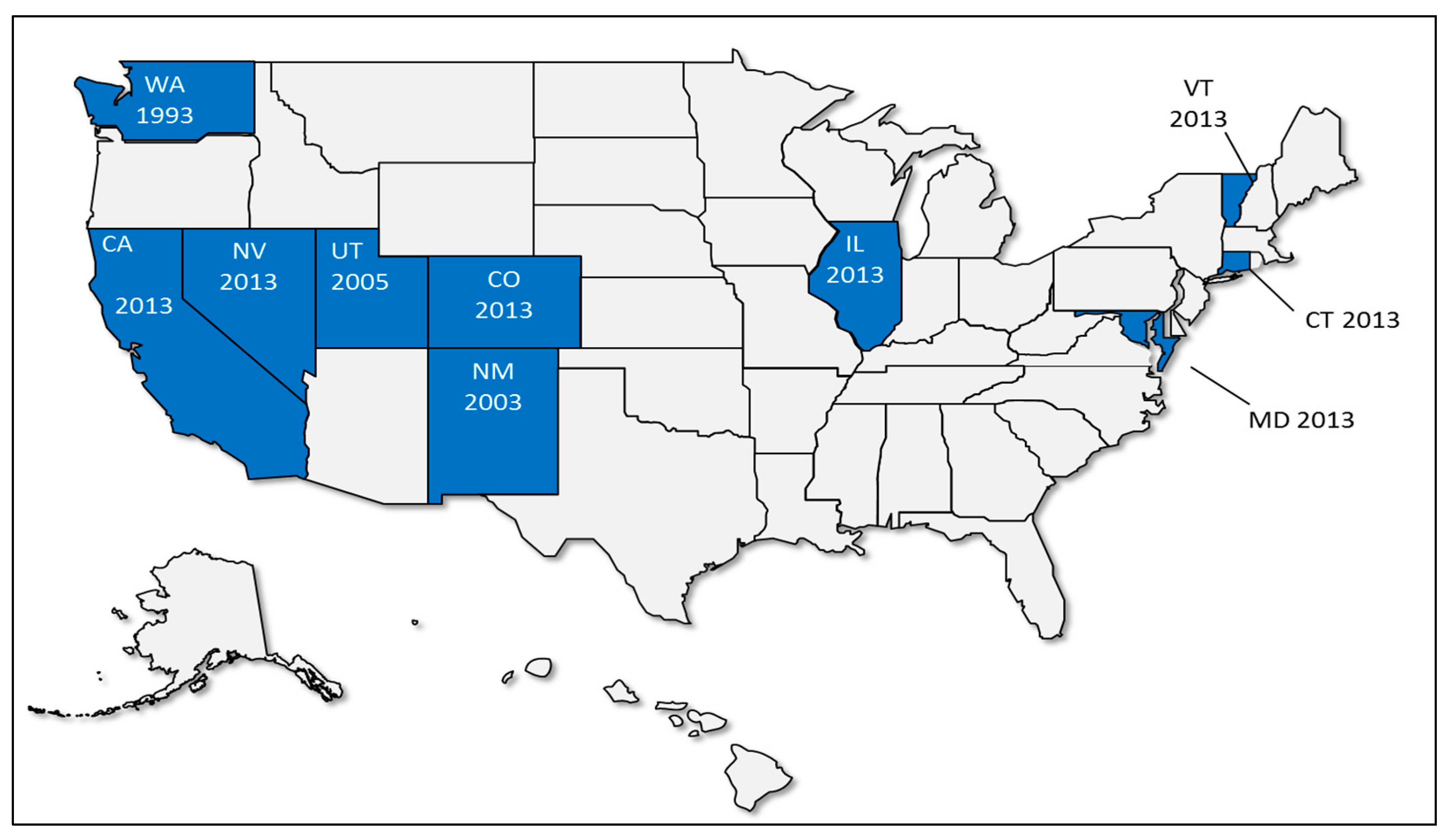

4.2.2. Driver’s Licenses and State-Issued Personal Identifiers

5. Discussion

“The bill I’m about to sign into law—Senate Bill 1070—represents another tool for our state to use as we work to solve a crisis we did not create and the federal government has refused to fix the crisis caused by illegal immigration and Arizona’s porous border”.—Arizona Governor Jan Brewer, 2010 [67]

“When a million people without their documents drive legally and with respect in the state of California, the rest of this country will have to stand up and take notice”.—California Governor Jerry Brown, 2013 [68]

6. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Paul Feldman. “Anti-Illegal Immigration Prop. 187 Keeps 2-To-1 Edge.” Los Angeles Times. 15 October 1994. Available online: http://articles.latimes.com/1994-10-15/news/mn-50380_1_illegal-immigrants (accessed on 2 October 2015).

- Paul Feldman. “Support for Prop. 187 Erodes, but It still Leads.” Los Angeles Times. 15 October 1994. Available online: http://articles.latimes.com/1994-10-27/news/mn-55339_1_times-poll (accessed on 2 October 2015).

- Kirin Kalia. “Top 10 of 2007-Issue #7: U.S. Cities Face Legal Challenges, and All 50 States Try Their Hand at Making Immigration-Related Laws.” In Migration Information Source: The Online Journal of the Migration Policy Institute. Washington: Migration Policy Institute, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- “National Conference of State Legislatures.” Available online: www.ncsl.org (accessed on 15 August 2015).

- Hiroshi Motomura. “Federalism, International Human Rights, and Immigration Exceptionalism.” University of Colorado Law Review 70 (1999): 1361–94. [Google Scholar]

- Cristina M. Rodriguez. “The Significance of the Local in Immigration Regulation.” Michigan Law Review 106 (2008): 567–642. [Google Scholar]

- Peter H. Schuck. “Taking immigration federalism seriously.” The University of Chicago Legal Forum, 2007, 57–92. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel J. Tichenor, and Alexandra Filindra. “Raising Arizona V. United States: Historical Patterns of American Immigration Federalism.” Lewis and Clark Law Review 16 (2012): 1215–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hiroshi Matomura. “Immigration outside the Law.” Columbia Law Review 108 (2010): 2037–97. [Google Scholar]

- Michael A. Olivas. “Immigration-Related State and Local Ordinances: Preemption, Prejudice, and the Proper Role for Enforcement.” The University of Chicago Legal Forum, 2007, 27–56. [Google Scholar]

- Michael J. Wishnie. “Laboratories of Bigotry? Devolution of the Immigration Power, Equal Protection, and Federalism.” New York University Law Review 76 (2001): 493–569. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas Guttentag. “The Forgotten Equality Norm in Immigration Preemption: Discrimination, Harassment and the Civil Rights Act Of 1870.” Duke Journal of Constitutional Law & Public Policy 8 (2013): 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick S. Roberts. “Dispersed Federalism as a New Regional Governance for Homeland Security.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 38 (2008): 416–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lina Newton. “Policy Innovation or Vertical Integration? A View of Immigration Federalism from the States.” Law and Policy 34 (2012): 113–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monica W. Varsanyi, Paul G. Lewis, Doris Marie Provine, and Scott Decker. “A Multilayered Jurisdictional Patchwork: Immigration Federalism in the United States.” Law & Policy 34 (2012): 138–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David Brian Robertson. Federalism and the Making of America. New York and London: Taylor Francis, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jorge M. Chavez, and Doris Marie Provine. “Race and the Response of State Legislatures to Unauthorized Immigrants.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences 623 (2009): 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doris Marie Provine, and Gabriella Sanchez. “Suspecting Immigrants: Exploring Links between Racialised Anxieties and Expanded Police Powers in Arizona.” Policing & Society 21 (2011): 468–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Karthick Ramakrishnan, and Tom Wong. Immigration Policies Go Local: The Varying Responses of Local Governments to Low-Skilled and Undocumented Immigration. Washington: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Otto Santa Ana, and Celeste González de Bustamante, eds. Arizona Firestorm: Global Immigration Realities, National Media, and Provincial Politics. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2012.

- Trip Gabriel. “Kris Kobach pushed Kansas to the Right. Now Kansas is Pushing Back.” The New York Times. 16 October 2014. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/17/us/politics/voter-id-firebrand-kris-kobach-takes-a-low-profile-kansas-office-out-of-the-shadows.html?_r=0 (accessed on 16 October 2014).

- Kris W. Kobach. “Reinforcing the Rule of Law: What States Can and Should Do to Reduce Illegal Immigration.” In Strange Neighbors: The Role of States in Immigration Policy. Edited by Gabriel Jackson Chin and Carissa Byrne Hessick. New York: New York University Press, 2012, pp. 99–129. [Google Scholar]

- Eli Saslow. “Conservative Expert on Immigration Law to Pursue Suit against Executive Action.” Washington Post. 22 November 2014. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/2014/11/22/f6d2b3fe-728a-11e4-ad12-3734c461eab6_story.html (accessed on 23 November 2014).

- Shawn Zeller. “Alec Racks up Wins in States.” CQ Weekly, 2014, 84. [Google Scholar]

- Gary Reich, and Jay Barth. “Immigration Restriction in the States: Contesting the Boundaries of Federalism? ” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 42 (2012): 422–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeme Boushey, and Adam Luedtke. “Immigrants across the U.S. Federal Laboratory: Explaining State-Level Innovation in Immigration Policy.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 11 (2011): 390–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter J. Spiro. “Learning to Live with Immigration Federalism.” Connecticut Law Review 29 (1997): 1627–46. [Google Scholar]

- Randal C. Archibold. “Judge Blocks Arizona’s Immigration Law.” The New York Times. 28 July 2010. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/07/29/us/29arizona.html?_r=0 (accessed on 22 September 2015).

- Rick Lyman. “In Georgia Law, A Wide-Angle View of Immigration.” The New York Times. 12 May 2006. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/2006/05/12/us/12georgia.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0 (accessed on 26 September 2015).

- Lieutenant Governor Casey Cagle. “Lt Governor Cagle: New Immigration Law Draws Line in the Sand.” In States News Service; 29 June 2007. Available online: http://ltgov.georgia.gov/press-releases/2007-06-29/lt-governor-cagle-new-immigration-law-draws-line-sand (accessed on 8 August 2008). [Google Scholar]

- States News Service. “Gov. Blunt Signs Legislation Protecting Missouri Families, Tax Dollars from Illegal Immigration.” 8 July 2008. Available online: http://www.infozine.com/news/stories/op/storiesView/sid/29277/ (accessed on 8 August 2008).

- States News Service. “Gov. Sanford Calls for Passage of Immigration Reforms.” States News Service, 29 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony Faiola. “States’ Immigrant Policies Diverge.” The Washington Post. 15 October 2007. Available online: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/10/14/AR2007101401266.html (accessed on 8 August 2008).

- States News Service. “Ellis Joins Nationwide Effort to Address Illegal Immigration.” States News Service, 31 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Reid Wilson. “States Take Action on Immigration as Congress Stalls.” The Washington Post. 21 January 2014. Available online: http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/govbeat/wp/2014/01/21/states-take-action-on-immigration-as-congress-stalls/ (accessed on 21 January 2014).

- Amy Worden. “Pa., N.J. Join Flood of Bills on Immigrants.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. 30 August 2007. Available online: http://articles.philly.com/2007-08-30/news/25230403_1_illegal-immigrants-immigration-laws-immigration-legislation (accessed on 8 August 2008).

- Shawn Zeller. “Real Id Act Makes State Officials Really Angry.” CQ Weekly, 2006, 2354–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lina Newton, and Brian E. Adams. “State Immigration Policies: Innovation, Cooperation, or Conflict? ” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 39 (2009): 408–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidney Plotkin, and William Scheuerman. Private Interest, Public Spending: Balanced-Budget Conservatism and the Fiscal Crisis. Boston: South End Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kitty Calavita. “The New Politics of Immigration: ‘Balanced-Budget Conservatism’ and the Symbolism of Proposition 187.” Social Problems 43 (1996): 284–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray Jacob Edelman. The Symbolic Uses of Politics. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond King. Making Americans: Immigration, Race and the Origins of the Diverse Democracy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mae Ngai. Impossible Subjects: Illegal Immigrants and the Making of Modern America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gerald L. Neuman. “The Lost Century of American Immigration Law (1776–1875).” Columbia Law Review 93 (1993): 1833–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John Higham. Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism 1860–1925. New York: Atheneum, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- The Passenger Cases, 48 U.S. (7 How) 283 (1849).

- Henderson V. Mayor of the City of New York, 92 U.S. 259 (1875).

- Chy Lung V. Freeman, 92 U.S. 276 (1875).

- Kitty Calavita. “The Paradoxes of Race, Class, Identity, and ‘Passing’: Enforcing the Chinese Exclusion Acts, 1882–1910.” Law and Social Inquiry 25 (2000): 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mae M. Ngai. “The Architecture of Race in American Immigration Law: A Reexamination of the Immigration Act of 1924.” Journal of American History 86 (1999): 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers M. Smith. Civic Ideals. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel J. Tichenor. Dividing Lines: The Politics of Immigration Control in America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chae Chan Ping V. United States, 130 U.S. 581 (1889).

- Fong Yue Ting V. United States, 149 U.S. 698 (1893).

- Edward George Hartmann. The Movement to Americanize the Immigrant. New York: Columbia University Press, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Hines V. Davidowitz, 312 U.S. 52 (1941).

- De Canas V. Bica, 424 U.S. 351 (1976).

- Thomas Byrne Edsall, and Mary D. Edsall. Chain Reaction: The Impact of Race, Rights and Taxes on American Politics. New York: Norton, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Plyler V. Doe, 457 U.S. 202 (1982).

- Toll V. Moreno, 458 U.S. 1 (1982).

- Chamber of Commerce of the United States v. Edmondson U.S. Court of Appeals (2010).

- Carissa Byrne Hessick, and Gabriel Jackson Chin. “Introduction.” In Strange Neighbors: The Role of States in Immigration Policy. Edited by Gabriel Jackson Chin and Carissa Byrne Hessick. New York: New York University Press, 2012, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Priscilla M. Regan, and Christopher J. Deering. “State Opposition to Real Id.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 39 (2009): 476–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josh Keller. “State Legislatures Debate Tuition for Illegal Immigrants.” Chronicle of Higher Education 53 (2007): A28. [Google Scholar]

- Jeanne Batalova, Sarah Hooker, and Randy Capps. Daca at the Two-Year Mark: A National and State Profile of Youth Eligible and Applying for Deferred Action. Washington: Migration Policy Institute, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- California State Assembly. “Assem. Bill No. 60, 2013–2014 Reg. Sess., ch. 524 2013 Cal. Stat. ”

- Los Angeles Times. “Remarks by Arizona Gov. Jan Brewer, as Provided by Her Office.” Los Angees Times. 23 April 2010. Available online: http://Latimesblogs.Latimes.Com/Washington/2010/04/Jan-Brewer-Arizona-Illegal-Immigration (accessed on 18 June 2015).

- Office of the Governor of the State of California. “Governor Brown Signs Ab 60.” 2013. Available online: http://Gov.Ca.Gov/News.Php?Id=18246 (accessed on 22 June 2015). [Google Scholar]

- Lina Newton. Illegal, Alien, or Immigrant: The Politics of Immigration Reform. New York: New York University Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security. “Real Id Enforcement in Brief.” 2013. Available online: Http://Www.Dhs.Gov/Real-Id-Enforcement-Brief (accessed on 1 June 2015). [Google Scholar]

- Ivan Moreno. “Battle Looming over Colorado Immigrant Driver’s Licenses.” Santa Fe New Mexican. 14 October 2015. Available online: Http://Www.Santafenewmexican.Com/News/Local_News/Battle-Looming-Over-Colorado-Immigrant-Driver-S-Licenses/Article_68a9055d-3b88-5727-Bb7a-0c9b72b28408.Html (accessed on 4 November 2015).

- National Immigration Law Center. “DACA Access to Driver’s Licenses.” 2015. Available online: Https://Www.Nilc.Org/Dacadriverslicenses2.Html (accessed on 1 October 2015).

- 1LULAC v. Wilson 1997.

- 2Omnibus bills package separate (and sometimes unrelated) measures into one bill which is then brought up in a legislature for a simple “yes” or “no” vote. In this case, state omnibus bills would combine immigration-related topics such as immigration law enforcement, employment eligibility enforcement, anti-human trafficking and appropriations to various agencies including those providing immigrant services.

- 4Justice Miller rejected the revenue-raising rationale behind the since the money was not used specifically for immigrant care.

- 5In Hines v. Davidowitz (1941), Pennsylvania’s Alien Registration Act of 1939 preceded Congress’s passage of the Alien Registration Act of 1940. The Pennsylvania Law was enjoined by 3 district judges who claimed the state law both infringed on congressional powers and also denied equal protection to aliens under section 16 of the Civil Rights Act of 1870. The Supreme Court concurred, with Justice Hugo Black arguing that implementation of the Pennsylvania law would create an obstacle to congressional objectives [56].

- 6Human trafficking laws appeared 97 times, and the content of these bills typically brought aspects of state law enforcement in concert with the national Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000, which aims to combat trafficking and shield victims and witnesses from prosecution.

- 7Voting rights are protected by federal legislation (the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and its extensions and renewals through 2007) and enforced via the Justice Department. Although states are in charge of redistricting for purposes of congressional reapportionment, when a state’s electoral maps are criticized for impinging on voting rights, these can land in the Justice Department or even the federal court.

© 2015 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Newton, L. Immigration Federalism as Ideology: Lessons from the States. Laws 2015, 4, 729-754. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws4040729

Newton L. Immigration Federalism as Ideology: Lessons from the States. Laws. 2015; 4(4):729-754. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws4040729

Chicago/Turabian StyleNewton, Lina. 2015. "Immigration Federalism as Ideology: Lessons from the States" Laws 4, no. 4: 729-754. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws4040729

APA StyleNewton, L. (2015). Immigration Federalism as Ideology: Lessons from the States. Laws, 4(4), 729-754. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws4040729