Trajectories and Risk Factors of Criminal Behavior among Females from Adolescence to Early Adulthood

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Trajectories of Criminal Behavior

3. Current Study

- Identify different trajectories of offending from adolescence through early adulthood among a large, representative sample of female adolescents;

- Identify the risk and protective factors that are related to membership in each trajectory during adolescence.

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. Variables 2

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | ||||

| Serious physical fight * | 0.24 (0.42) | 0.13 (0.34) | - | 0.12 (0.15) |

| Hurt someone | 0.11 (0.31) | 0.04 (0.20) | 0.02 (0.15) | 0.01 (0.07) |

| Group fight | 0.17 (0.38) | 0.14 (0.34) | 0.03 (0.18) | 0.01 (0.11) |

| Pulled a knife/weapon out | 0.02 (0.15) | 0.02 (0.14) | 0.01 (0.07) | 0.01 (0.11) |

| Weapon to steal | 0.03 (0.17) | 0.02 (0.14) | 0.01 (0.09) | 0.01 (0.06) |

| Burglary | 0.03 (0.18) | 0.03 (0.16) | 0.01 (0.10) | 0.01 (0.06) |

| Stole something worth more than $50 | 0.03 (0.18) | 0.03 (0.17) | 0.02 (0.14) | 0.01 (0.10) |

| Stole something worth less than $50 | 0.17 (0.36) | 0.14 (0.35) | 0.05 (0.22) | 0.02 (0.15) |

| Sold drugs | 0.04 (0.20) | 0.04 (0.19) | 0.04 (0.19) | 0.02 (0.14) |

| Deliberately damaged property | 0.13 (0.33) | 0.09 (0.29) | 0.05 (0.21) | 0.02 (0.15) |

3.1.2. Analysis

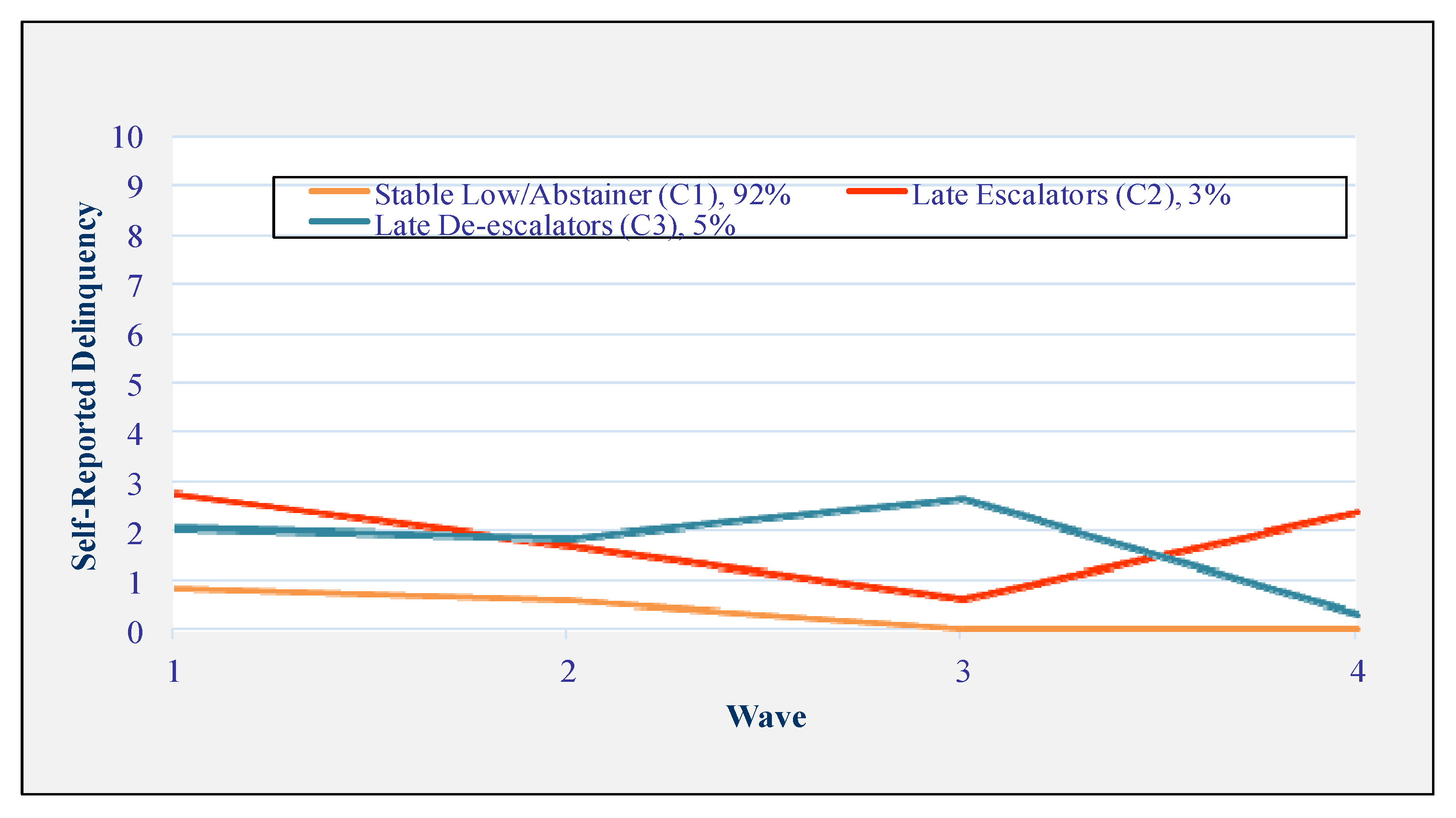

3.2. Results

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Wave 2 | 0.54 | - | - | - |

| Wave 3 | 0.19 | 0.22 | - | - |

| Wave 4 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.26 | - |

| BIC | Log Likelihood | Entropy | LMR | LRT | Average Latent ClassProbabilities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Classes | 49262.86 | −24575.89 | 0.98 | 4435.82 (p = 0.40) | 4334.36 (p = 0.40) | 1.00, 0.95 |

| 3-Classes | 45833.20 | −21896.54 | 0.99 | 3472.38 (p = 0.02) | 3392.96 (p = 0.02) | 1.00, 0.99, 0.99 |

| 4-Classes | 40083.29 | −19943.39 | 0.98 | 5189.53 (p = 0.68) | 5070.84 (p = 0.68) | 0.91, 0.99, 0.99, 0.99 |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 Stable Low/Abstainers | C2 Late Escalators | C3 Late De-Escalators | |

| Self-Control a,b | 4.61 (3.17) | 5.91 (3.54) | 5.83 (3.32) |

| Depression a,b,c | 10.50 (7.17) | 14.02 (8.43) | 11.98 (8.07) |

| Self-Esteem b | 5.31 (1.82) | 5.27 (1.98) | 5.57 (2.03) |

| Parental Attachment b | 14.85 (1.81) | 15.11 (1.83) | 15.14 (1.84) |

| Parental Involvement a,c | 1.51 (1.02) | 1.29 (0.92) | 1.60 (1.06) |

| Parental Control | 4.98 (1.66) | 4.98 (1.74) | 4.95 (1.64) |

| Peer Substance Use a,c | 2.24 (2.52) | 3.15 (2.77) | 2.50 (2.70) |

| Marijuana Use a,b | 0.82 (4.79) | 2.50 (9.75) | 2.15 (9.67) |

| Cigarette Use a,c | 3.70 (8.96) | 6.82 (11.52) | 4.47 (9.21) |

| School Attachment a,b | 18.10 (4.81) | 17.32 (4.90) | 17.43 (5.16) |

| Truancy | 8.72 (13.24) | 10.10 (16.05) | 6.63 (6.99) |

| Percentage | Percentage | Percentage | |

| Frequency of Getting Drunk a | |||

| Never | 76.6% | 58.8% | 69.6% |

| 1–2 times | 11.7% | 19.4% | 14.3% |

| Less than once a month | 4.9% | 10.3% | 6.3% |

| Two or more times per month | 3.8% | 5.5% | 5.5% |

| At least once per week | 3.1% | 6.1% | 4.2% |

| Use of Other Drugs a | |||

| No | 96.1% | 90.9% | 89.7% |

| Yes | 3.9% | 9.1% | 10.3% |

| Stable Low/Abstainers → Late Escalators | Stable Low/Abstainers → Late De-Escalators | Late Escalators → Late De-Escalators | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RRR (CI) | RRR (CI) | RRR (CI) | |

| Self-Control | 1.03 (0.97–1.09) | 1.09 (1.04–1.14) *** | 1.06 (0.99–1.13) |

| Depression | 1.06 (1.03–1.08) *** | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | 0.95 (0.92–0.98) ** |

| Self-Esteem | 0.84 (0.76–0.93) ** | 1.01 (0.93–1.11) | 1.21 (1.06–1.38) ** |

| Parental Attachment | 1.00 (0.92–1.10) | 1.07 (0.99–1.16) | 1.07 (0.95–1.21) |

| Parental Involvement | 0.87 (0.73–1.03) | 1.17 (1.02–1.37) * | 1.35 (1.08–1.67) ** |

| Peer Substance Use | 1.02 (0.95–1.05) | 1.01 (0.94–1.08) | 0.99 (0.89–1.09) |

| Frequency of Getting Drunk | 1.18 (1.00–1.39) | 1.08 (0.91–1.27) | 0.91 (0.73–1.14) |

| Marijuana Use | 1.01 (0.99–1.07) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) |

| Cigarette Use | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) | 0.98 (0.96–1.01) |

| Use of Other Drugs | 1.50 (0.80–2.83) | 2.09 (1.22–3.57) ** | 1.40 (0.63–3.07) |

| School Attachment | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) | 1.00 (0.96–1.04) | 1.00 (0.95–1.07) |

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Add Health | National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health; |

| LCA | Latent Class Analysis; |

| LMR | Lo-Mendall Rubin; |

| LRT | Lo-Mendall Rubin Likelihood Ratio Test; |

| SE | standard error; |

| SD | standard deviation; |

| RRR | relative risk ratio. |

References

- Howard N. Snyder. “Juvenile Arrests, 1992.” In Office of Juvenile Justice Delinquency and Prevention; 1994. Available online: https://www.ncjrs.gov/txtfiles/fs-9413.txt (accessed on 19 September 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Charles Puzzanchera. “Juvenile Arrests, 2011.” In Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice Delinquency and Prevention; 2013. Available online: http://www.ojjdp.gov/pubs/244476.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Sarah C. Walker, Ann Muno, and Cheryl Sullivan-Colglazier. “Principles in Practice: A Multistate Study of Gender-Responsive Reforms in the Juvenile Justice System.” Crime & Delinquency 58 (2012): 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Meda Chesney-Lind, and Randall G. Shelden. Girls, Delinquency, and Juvenile Justice. Belmont: Wadsworth, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pernilla Johansson, and Kimberly Kempf-Leonard. “A Gender-Specific Pathway to Serious, Violent, and Chronic Offending?: Exploring Howell’s Risk Factors for Serious Delinquency.” Crime & Delinquency 55 (2009): 216–40. [Google Scholar]

- Mark A. Cohen, Alex R. Piquero, and Wesley G. Jennings. “Monetary Costs of Gender and Ethnicity Disaggregated Group-Based Offending.” American Journal of Criminal Justice 35 (2010): 159–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyeon Park, Merry Morash, and Tia Stevens. “Gender Differences in Predictors of Assaultive Behavior in Late Adolescence.” Youth Violence & Juvenile Justice 8 (2010): 314–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jennifer M. Reingle, Wesley G. Jennings, and Mildred M. Maldonado-Molina. “Risk and Protective Factors for Trajectories of Violent Delinquency among a Nationally Representative Sample of Early Adolescents.” Youth Violence & Juvenile Justice 10 (2012): 260–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin Aguilar, L. Alan Sroufe, Byron Egeland, and Elizabeth Carlson. “Distinguishing the Early-onset/Persistent and Adolescence-onset Antisocial Behavior Types: From Birth to 16 Years.” Development and Psychopathology 12 (2000): 109–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alex R. Piquero. “Taking Stock of Developmental Trajectories of Criminal Activity over the Life Course.” In The Long View of Crime: A Synthesis of Longitudinal Research. New York: Springer, 2008, pp. 23–78. [Google Scholar]

- Terrie E. Moffitt. “Adolescence-limited and Life-course-persistent Antisocial Behavior: A Developmental Taxonomy.” Psychological Review 100 (1993): 674–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alex R. Piquero. “Assessing the Relationships between Gender, Chronicity, Seriousness, and Offense Skewness in Criminal Offending.” Journal of Criminal Justice 28 (2000): 103–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ick-Joong Chung, Karl G. Hill, J. David Hawkins, Lewayne D. Gilchrist, and Daniel S. Nagin. “Childhood predictors of Offense Trajectories.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 39 (2002): 60–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David M. Fergusson, and John L. Horwood. “Male and Female Offending Trajectories.” Development and Psychopathology 14 (2002): 159–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesley G. Jennings, and Jennifer M. Reingle. “On the Number and Shape of Developmental/Life-Course Violence, Aggression, and Delinquency Trajectories: A state-of-the-art Review.” Journal of Criminal Justice 40 (2012): 472–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David Huizinga, Shari Miller, and The Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. “Developmental Sequences of Girls’ Behavior.” U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice Delinquency and Prevention, 2013 December. Available online: http://www.ojjdp.gov/pubs/238276.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Shari Miller, Patrick S. Malone, and Kenneth A. Dodge. “Developmental Trajectories of Boys’ and Girls’ Delinquency: Sex Differences and Links to Later Adolescent Outcomes.” Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 38 (2010): 1021–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennifer M. Reingle, Wesley G. Jennings, and Mildred M. Maldonado-Molina. “The Mediated Effect of Contextual Risk Factors on Trajectories of Violence: Results from a Nationally Representative, Longitudinal Sample of Hispanic Adolescents.” American Journal of Criminal Justice 36 (2011): 327–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman A. White, and Alex R. Piquero. “A Preliminary Empirical Test of Silverthorn and Frick’s Delayed-onset Pathway in Girls using an Urban, African-American, US-Based Sample.” Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health 14 (2004): 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debra J. Pepler, Depeng Jiang, Wendy M. Craig, and Jennifer Connolly. “Developmental Trajectories of Girls’ and Boys’ Delinquency and Associated Problems.” Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 38 (2010): 1033–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alex R. Piquero, and He Len Chung. “On the Relationships between Gender, Early Onset, and the Seriousness of Offending.” Journal of Criminal Justice 29 (2001): 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debra A. Murphy, Mary-Lynn Brecht, David Huang, and Diane M. Herbeck. “Trajectories of Delinquency from Age 14 to 23 in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth sample.” International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 17 (2012): 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthew C. Aalsma, and Daniel K. Lapsley. “A Typology of Adolescent Delinquency: Sex Differences and Implications for Treatment.” Criminal Behaviour & Mental Health 11 (2001): 173–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persephanie Silverthorn, Paul J. Frick, and Richard Reynolds. “Timing of Onset and Correlates of Severe Conduct Problems in Adjudicated Girls and Boys.” Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 23 (2001): 171–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao Zheng, and H. Harrington Cleveland. “Identifying Gender-Specific Developmental Trajectories of Nonviolent and Violent Delinquency from Adolescence to Young Adulthood.” Journal of Adolescence 36 (2013): 371–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deborah Gorman-Smith, and Rolf Loeber. “Are Developmental Pathways in Disruptive Behaviors the Same for Girls and Boys? ” Journal of Child and Family Studies 14 (2005): 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen D. Whitney, Lynette M. Renner, and Todd I. Herrenkohl. “Gender Differences in Risk and Promotive Classifications Associated with Adolescent Delinquency.” The Journal of Genetic Psychology 171 (2010): 116–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machteld Hoeve, Juditch S. Dubas, Veroni I. Eichelsheim, Peter H. van der Laan, Wilma Smeenk, and Jane R. M. Gerris. “The Relationship between Parenting and Delinquency: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 37 (2009): 749–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dana Peterson, and Kirstin A. Morgan. “Sex Differences and the Overlap in Youths’ Risk Factors for Onset of Violence and Gang Involvement.” Journal of Crime & Justice 37 (2014): 129–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanne Belknap, and Kristi Holsinger. “The Gendered Nature of Risk Factors for Delinquency.” Feminist Criminology 1 (2006): 48–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abigail A. Fagan, M. Lee Van Horn, Susan Antaramian, and J. David Hawkins. “How do Families Matter? Age and Gender Differences in Family Influences on Delinquency and Drug Use.” Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 9 (2011): 150–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dana J. Hubbard, and Travis C. Pratt. “A Meta-Analysis of the Predictors of Delinquency among Girls.” Journal of Offender Rehabilitation 34 (2002): 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abigail A. Fagan, M. Lee Van Horn, J. David Hawkins, and Michael W. Arthur. “Gender Similarities and Differences in the Association between Risk and Protective Factors and Self-Reported Serious Delinquency.” Prevention Science 8 (2007): 115–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisa M. Broidy, Daniel S. Nagin, Richard E. Tremblay, John E. Bates, Bobby Brame, Kenneth A. Dodge, David Fergusson, John L. Horwood, Rolf Loeber, Robert Laird, and et al. “Developmental Trajectories of Childhood Disruptive Behaviors and Adolescent Delinquency: A Six-site, Cross-National Study.” Developmental Psychology 39 (2003): 222–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teresa C. LaGrange, and Robert A. Silverman. “Low Self-Control and Opportunity: Testing the General Theory of Crime as an Explanation for Gender Differences in Delinquency.” Criminology 37 (1999): 41–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majone Steketee, Marianne Junger, and Josine Junger-Tas. “Sex Differences in the Predictors of Juvenile Delinquency: Females are more Susceptible to Poor Environments; Males are Influenced more by Low Self-Control.” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 29 (2013): 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizabeth Cauffman, Francis J. Lexcen, Asha Goldweber, Elizabeth P. Shulman, and Thomas Grisso. “Gender Differences in Mental Health Symptoms among Delinquent and Community Youth.” Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 5 (2007): 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael K. Ostrowsky. Self-Medication and Violent Behavior. El Paso: LFB Scholarly Publishing, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory D. Webster, Lee A. Kirkpatrick, John B. Nezlek, Veronica C. Smith, and Layne E. Paddock. “Different Slopes for Different Folks: Self-esteem Instability and Gender as Moderators of the Relationship between Self-Esteem and Attitudinal Aggression.” Self & Identity 6 (2007): 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannes A. Landsheer, and C. van Dijkum. “Male and Female Delinquency Trajectories from Pre through Middle Adolescence and their Continuation in Late Adolescence.” Adolescence 40 (2005): 729–48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bo Wang, Lynette Deveaux, Xiaoming Li, Sharon Marshall, Xinguang Chen, and Bonita Stanton. “The Impact of Youth, Family, Peer and Neighborhood Risk Factors on Developmental Trajectories of Risk Involvement from Early through Middle Adolescence.” Social Science & Medicine 106 (2014): 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesley G. Jennings, Mildred M. Maldonado-Molina, Alex R. Piquero, Candice L. Odgers, Hector Bird, and Glorisa Canino. “Sex Differences in Trajectories of Offending among Puerto Rican Youth.” Crime & Delinquency 56 (2010): 327–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David P. Farrington, and Kate A. Painter. Gender Differences in Offending: Implications for Risk-Focused Prevention. London: Home Office RDA, 2004, Available online: http://www.crim.cam.ac.uk/people/academic_research/david_farrington/olr0904.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2014).

- Terrie E. Moffitt. “Juvenile Delinquency and Attention Deficit Disorder: Boys’ Developmental Trajectories from Age 3 to Age 15.” Child Development 61 (1990): 893–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David S. Nagin, David P. Farrington, and Terrie E. Moffitt. “Life-course Trajectories of Different Types of Offenders.” Criminology 33 (1995): 111–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathleen M. Harris. “The Add Health Study: Design and Accomplishments.” Available online: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/data/guides/DesignPaperWIIV.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2013).

- Kim Chantala, and Joyce Tabor. “Strategies to Perform a Design-Based Analysis using the Add Health data.” Available online: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/data/guides/weight1.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2013).

- Naomi Brownstein, William D. Kalsbeck, Joyce Tabor, Pamela Entzel, Eric Daza, and Kathleen M. Harris. “Non-Response in Wave IV of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health.” Available online: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/data/guides/W4_nonresponse.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2013).

- Martha Gault-Sherman. “It’s a Two-way Street: The Bidirectional Relationship between Parenting and Delinquency.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 41 (2012): 121–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monica K. Johnson, Robert Crosnoe, and Lyssa L. Thaden. “Gendered Patterns in Adolescents’ School Attachment.” Social Psychology Quarterly 69 (2006): 284–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilary D. Joyce, and Theresa J. Early. “The Impact of School Connectedness and Teacher Support on Depressive Symptoms in Adolescents: A Multilevel Analysis.” Children and Youth Services Review 39 (2014): 101–07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renee V. Galliher, Sharon S. Rostosky, and Hannah K. Hughes. “School Belonging, Self-Esteem, and Depressive Symptoms in Adolescents: An Examination of Sex, Sexual Attraction Status, and Urbanicity.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 33 (2004): 235–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gene H. Brody, Xiaojia Ge, Rand Conger, Fredrick X. Gibbons, Velma M. Murry, Meg Gerrard, and Ronald L. Simons. “The Influence of Neighborhood Disadvantage, Collective Socialization, and Parenting on African American Children’s Affiliation with Deviant Peers.” Child Development 72 (2001): 1231–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott R. Weaver, and Hazel M. Prelow. “A Mediated-moderation Model of Maternal Parenting Style, Association with Deviant Peers, and Problem Behaviors in Urban African American and European American Adolescents.” Journal of Child and Family Studies 14 (2005): 343–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arielle R. Deutsch, Lisa J. Crockett, Jennifer M. Wolff, and Stephen T. Russell. “Parent and Peer Pathways to Adolescent Delinquency: Variations by Ethnicity and Neighborhood Context.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 41 (2012): 1078–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mary R. Gillmore, Sandra S. Butler, Mary J. Lohr, and Lewayne Gilchrist. “Substance Use and Other Factors Associated with Risky Sexual Behavior among Pregnant Adolescents.” Family Planning Perspectives 24 (1992): 255–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheryl A. Hemphill, Todd I. Herrenkohl, Andrea N. LaFazia, Barbara J. McMorris, John W. Toumbourou, Michael W. Arthur, Richard F. Catalano, J. David Hawkins, and Lyndal Bond. “Comparison of the Structure of Adolescent Problem Behavior in the United States and Australia.” Crime & Delinquency 53 (2007): 303–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dina Perrone, Christopher J. Sullivan, Travis C. Pratt, and Satenik Margaryan. “Parental Efficacy, Self-Control, and Delinquency: A Test of a General Theory of Crime on a Nationally Representative Sample of Youth.” International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 48 (2004): 298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph O. Baker. “The expression of low self-control as problematic drinking in adolescents: An integrated control perspective.” Journal of Criminal Justice 38 (2011): 237–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew M. Guest, and Nick Mcree. “A School-Level Analysis of Adolescent Extracurricular Activity, Delinquency, and Depression: The Importance of Situational Context.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 38 (2009): 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R. Barry Ruback, Valerie A. Clark, and Cody Warner. “Why Are Crime Victims at Risk of Being Victimized Again? Substance Use, Depression, and Offending as Mediators of the Victimization-Revictimization Link.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 29 (2013): 157–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brianna Remster. “Self-Control and the Depression–Delinquency Link.” Deviant Behavior 35 (2014): 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan L. McCutcheon. “Basic Concepts and Procedures in Single and Multiple Group Latent Class Analysis.” In Applied Latent Class Analysis. Edited by Jacques A. Hagenaars and Allan L. McCutcheon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002, pp. 56–88. [Google Scholar]

- Karen L. Nylund, Tihomir Asparouhov, and Bengt O. Muthen. “Deciding on the Number of Classes in Latent Class Analysis and Growth Mixture Modeling: A Monte Carlo Simulation Study.” Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 14 (2007): 535–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yungtai T. Lo, Nancy R. Mendell, and Donald B. Rubin. “Testing the number of components in a normal mixture.” Biometrika 88 (2001): 767–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeroen K. Vermunt, and Jay Magidson. “Latent Class Analysis.” In The Sage Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods. Edited by Michael S. Lewis-Beck, Alan E. Bryman and Tim F. Liao. Newbury Park: Sage, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bengt O. Muthén, and Linda K. Muthén. Mplus User’s Guide, 3rd ed. Los Angles: Muthén & Muthén, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Victor van der Geest, Arjan Blokland, and Catrien Bijleveld. “Delinquent Development in a Sample of High-Risk Youth: Shape, Content, and Predictors of Delinquent Trajectories from Age 12 to 32.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 46 (2009): 111–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steven A. McFadyen-Ketchum, John E. Bates, Kenneth A. Dodge, and Gregory S. Pettit. “Patterns of Change in Early Childhood Aggressive-Disruptive Behavior: Gender Differences in Predictions from Early Coercive and Affectionate Mother-Child Interactions.” Child Development 67 (1996): 2417–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amy V. D’Unger, Kenneth C. Land, and Patricia L. McCall. “Sex Differences in Age Patterns of Delinquent/Criminal Careers: Results from Poisson Latent Class Analyses of the Philadelphia Cohort Study.” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 18 (2002): 349–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin B. Lahey, Carol A. Van Hulle, Irwin D. Waldman, Joseph Lee Rodgers, Brian M. D’Onofrio, Steven Pedlow, Paul Rathouz, and Kate Keenan. “Testing Descriptive Hypotheses Regarding Sex Differences in the Development of Conduct Problems and Delinquency.” Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 34 (2006): 730–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick H. Tolan, and Peter Thomas. “The Implications of Age of Onset for Delinquency Risk II: Longitudinal Data.” Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 23 (1995): 157–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynn Kratzer, and Sheilagh Hodgins. “A Typology of Offenders: A Test of Moffitt’s Theory among Males and Females from Childhood to Age 30.” Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health 9 (1999): 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persephanie Silverthorn, and Paul J. Frick. “Developmental Pathways to Antisocial Behavior: The Delayed-onset Pathway in Girls.” Development and Psychopathology 11 (1999): 101–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofia Diamantopoulou, Frank C. Verhulst, and Jan van der Ende. “Gender Differences in the Development and Adult Outcome of Co-occurring Depression and Delinquency in Adolescence.” Journal of Abnormal Psychology 120 (2011): 644–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristen C. Kling, and Janet Shibley Hyde. “Gender differences in self-esteem: A meta-analysis.” Psychological Bulletin 125 (1999): 470–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susan Nolen-Hoeksema, and Joan S. Girgus. “Emergence of Gender Differences in Depression during Adolescence.” Psychological Bulletin 115 (1994): 424–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allison Foley. “The Current State of Gender-Specific Delinquency Programming.” Journal of Criminal Justice 36 (2008): 262–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana L. Haynie. “Contexts of Risk? Explaining the Link between Girls’ Pubertal Development and their Delinquency Involvement.” Social Forces 82 (2003): 355–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbert S. Elliott, David Huizinga, and Scott W. Menard. Multiple Problem Youth: Delinquency, Substance Abuse, and Mental Health Problems. New York: Springer, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- David Huizinga, and Cynthia Jakob-Chien. “The Contemporaneous Co-occurrence of Serious and Violent Juvenile Offender and Other Problem Behaviors.” In Serious and Violent Juvenile Offenders: Risk Factors and Successful Interventions. Edited by Roll Loeber and David P. Farrington. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 1998, pp. 47–67. [Google Scholar]

- Scott Menard, Sharon Mihalic, and David Huizinga. “Drugs and Crime Revisited.” Justice Quarterly 18 (2001): 269–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolf Loeber, and David P. Farrington. “Young Children Who Commit Crime: Epidemiology, Developmental Origins, Risk Factors, Early Interventions, and Policy Implications.” Development and Psychopathology 12 (2000): 737–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabnam Javdani, Naomi Sadeh, and Edelyn Verona. “Expanding Our Lens: Female Pathways to Antisocial Behavior in Adolescence and Adulthood.” Clinical Psychology Review 31 (2011): 1324–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leoniek Kroneman, Rolf Loeber, and Alison E. Hipwell. “Is Neighborhood Context Differently Related to Externalizing Problems and Delinquency for Girls Compared with Boys? ” Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 7 (2004): 109–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabnam Javdani, Erin M. Rodriguez, Sara R. Nichols, Erin Emerson, and Geri R. Donenberg. “Risking it for Love: Romantic Relationships and Early Pubertal Development Confer Risk for Later Disruptive Behavior Disorders in African-American Girls Receiving Psychiatric Care.” Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 2014, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magda Stouthamer-Loeber, Rolf Loeber, David P. Farrington, Quanwu Zhang, Welmoet van Kammen, and Eugene Maguin. “The Double Edge of Protective and Risk Factors for Delinquency: Interrelations and Developmental Patterns.” Development and Psychopathology 5 (1993): 683–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edward P. Mulvey, Laurence Steinberg, Jeffrey Fagan, Elizabeth Cauffman, Alex R. Piquero, Laurie Chassin, George P. Knight, Robert Brame, Carol A. Schubert, Thomas Hecker, and et al. “Theory and Research on Desistance from Antisocial Activity among Serious Adolescent Offenders.” Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 2 (2004): 213–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephanie T. Lanza, and Brittany L. Rhoades. “Latent Class Analysis: An Alternative Perspective on Subgroup Analysis in Prevention and Treatment.” Prevention Science 14 (2013): 157–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charles D. Ayers, James H. Williams, J. David Hawkins, Peggy L. Peterson, Richard F. Catalano, and Robert D. Abbott. “Assessing Correlates of Onset, Escalation, De-escalation, and Desistance of Delinquent Behavior.” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 15 (1999): 277–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadine Lanctŏt, and Marc LeBlanc. “Explaining Deviance by Adolescent Females.” Crime and Justice: A Review of Research 29 (2002): 113–202. [Google Scholar]

- 1Response rates for each wave ranged from 77% to 89%.

- 2See Harris et al. for a detailed description of each of the study variables [46].

- 3The Wave 3 interview did not include a measure of past year involvement in a serious physical fight. Therefore, the wave 3 index ranged from 0 to 9.

- 4There were no significant differences in the four delinquency indices across the females included in the sample and those excluded (due to not participating in all four waves of data or having invalid sampling weights). In addition, the original Add Health investigators concluded that the bias due to nonresponse was small in magnitude. For the delinquency and violence indices specifically, they concluded that the bias was not significantly different from zero [48].

- 5We chose to include substance use as a predictor of delinquent trajectories instead of a form of delinquent behavior for many reasons. Indeed, both substance use and delinquent behavior are forms of deviant behavior. However, there are also important differences in the characteristics of substance use and delinquent behavior that suggest that these behaviors are conceptually distinct. A number of studies have found substance use and delinquent behavior to be distinct dimensions of deviant or risk-taking behavior [56,57]. Since the goal of this study was to examine trajectories of delinquent behavior among girls over time, we felt that is was necessary to include substance use as a risk factor for delinquent behavior, rather than a form of delinquent behavior itself.

- 6Growth mixture models and latent class growth analyses were considered, but due to the low levels of delinquency found at each of the four waves, the low number of time points available, and the complex nature of measuring growth over time, a parsimonious LCA model was chosen.

- 7Missing delinquency data ranged from 0.8% in Wave 1 to 10% in Wave 4. All study participants had at least one wave of valid delinquency data. Mplus uses full information maximum likelihood to estimate the latent classes based on available information.

- 8Age and race were included as control variables. Age was a continuous variable representing age at the time of the Wave 1 interview. The average age at Wave 1 was 15.2 (SD = 1.6). Race was a categorical variable coded as White (64%), Black (23%), and Other (13%).

- 9The correlations among the risk and protective factors ranged from −0.08 to 0.52 and all variation inflation factors were less than 2.0.

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krupa, J.M.; Childs, K.K. Trajectories and Risk Factors of Criminal Behavior among Females from Adolescence to Early Adulthood. Laws 2014, 3, 651-673. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws3040651

Krupa JM, Childs KK. Trajectories and Risk Factors of Criminal Behavior among Females from Adolescence to Early Adulthood. Laws. 2014; 3(4):651-673. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws3040651

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrupa, Julie M., and Kristina K. Childs. 2014. "Trajectories and Risk Factors of Criminal Behavior among Females from Adolescence to Early Adulthood" Laws 3, no. 4: 651-673. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws3040651

APA StyleKrupa, J. M., & Childs, K. K. (2014). Trajectories and Risk Factors of Criminal Behavior among Females from Adolescence to Early Adulthood. Laws, 3(4), 651-673. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws3040651