Custodian of Autonomous AI Systems in the UAE: An Adapted Legal Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Application of the Custodianship Provisions to the Operator of AI System

2.1. Expanding the Interpretation of the Concept of “Thing”

2.2. Legal Custodianship as an Alternative to Actual Custodianship: A Suitable Solution

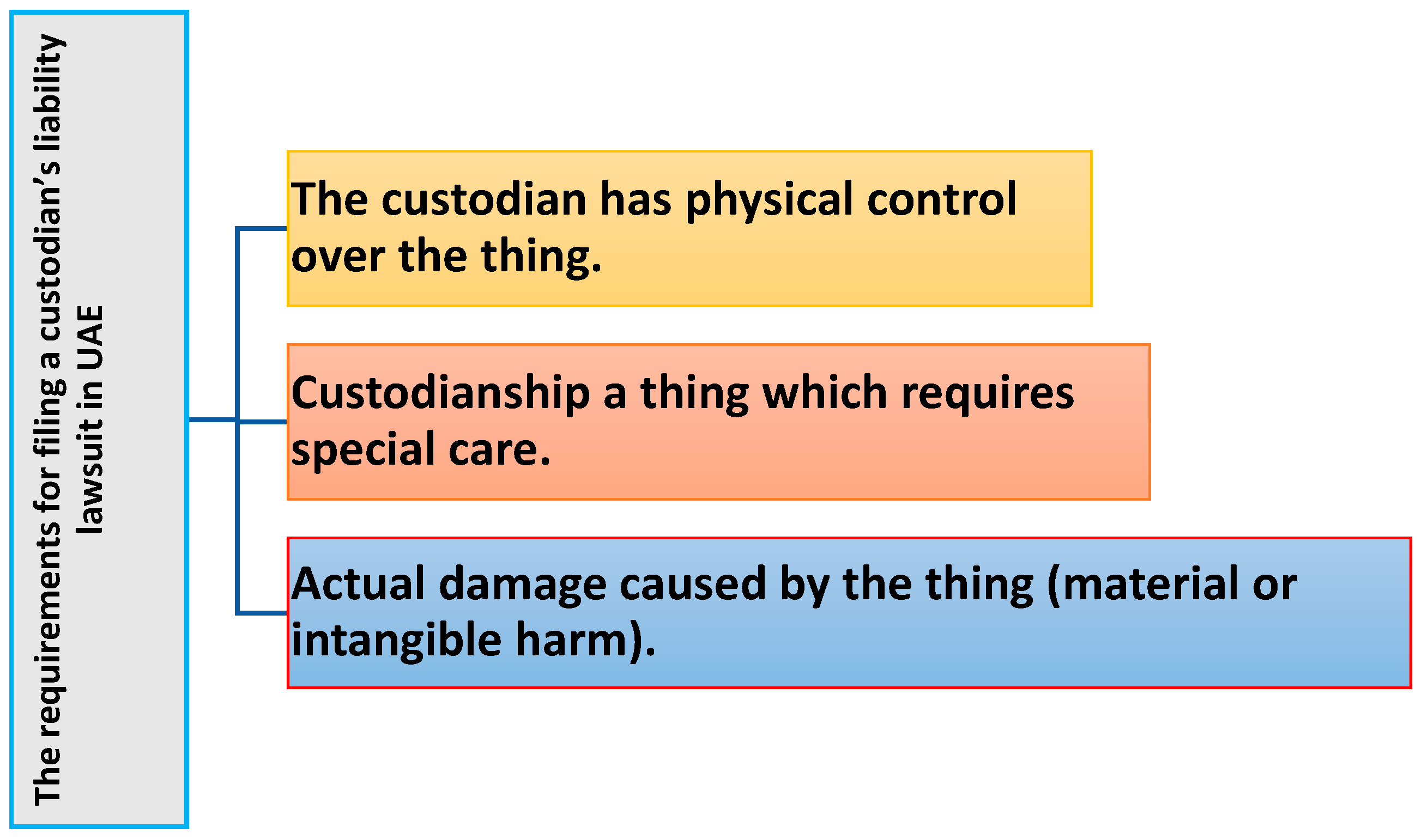

3. Requirements for the Safe and Legal Operation of AI Systems

3.1. Having an Effective Mechanism to Identify the Custodian of AI Systems: Mandatory Registration of AI Systems

3.2. Compulsory Insurance Against Liability Arising from the Operation of AI Systems

3.3. Compensate the Injured Decisively

3.4. Limitation of Liability for AI Operation Claims

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdou, Mohamed Morsi. 2024. The problem of legal recognition of an artificial intelligence system as an inventor—Comparative study. Journal of Law 1: 317–58. [Google Scholar]

- Abdou, Mohamed Morsi, and Shikha Alqydi. 2024. The issue of classifying smart pontoons as ships according to UAE Maritime Law. University of Sharjah (UoS) Journal of Law Sciences 21: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Abed, Fayed A. A. 2011. Automatic Compensation for Damages through Insurance and Guarantee Funds—A Comparative Study in Egyptian and French Law. Helwan Law Journal for Legal and Economic Studies 25: 11. [Google Scholar]

- Abu Dhabi Court of Cassation. 2016. Case Number: 590, UAE. February 1. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sanhouri, Abdelrazaq. 1952. The Mediator in Explanation of the New Civil Law, The Theory of Commitment in General, 3rd ed. Cairo: Egyptian Universities Publishing House Press. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sanhouri, Abdelrazaq. n.d. Explanation of the Civil Law, Property Rights with a Detailed Statement of Things and Money. Beirut: Arab Heritage Revival House.

- Bensamoun, Alexandra. 2023. Intelligence artificielle—Maîtriser les risques de l’intelligence artificielle: Entre éthique, responsabilisation et responsabilité. La Semaine Juridique Edition Générale 5: 181. [Google Scholar]

- Borghetti, Jean-Sébastien. 2019. Civil Liability for Artificial Intelligence: What Should its Basis Be? La Revue des Juristes de Sciences Po 17: 94–102. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, Georg. 2019. New Liability Concepts: The Potential of Insurance and Compensation Funds. In Liability for Artificial Intelligence and the Internet of Things. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG, pp. 145–63. [Google Scholar]

- Calo, Ryan. 2015. Robotics and the Lessons of Cyberlaw. California Law Review 103: 538. [Google Scholar]

- Cristono Almonte v. Averna Vision, and Robotics, Inc. 2015. Case Number: 11–CV–1088 EAW, United States District Court, W.D. New York, 31 August 2015. Available online: https://www.casemine.com/judgement/us/5914fc14add7b049349b1637 (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- De Mot, Jeff, and Louis Visscher. 2014. Custodian Liability. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Eling, Martin. 2019. How Insurance Can Mitigate AI Risks. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/how-insurance-can-mitigate-ai-risks/ (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Européenne Commission. 2020. Intelligence Artificielle, Une Approche Européenne Axée Sur L’excellence et la Confiance. Bruxelles: Office des Publications de l’Union Européenne. [Google Scholar]

- Faure, Michael, and Shu Li. 2022. Artificial Intelligence and (Compulsory) Insurance. Journal of European Tort Law 13: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French Court of Cassation. 2006. Case Namber: 04-15995, Paris, 25 April 2006. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/juri/id/JURITEXT000007499275 (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Gonzalez Prod. Sys., Inc. v. Martinrea Int’l Inc. 2016. Available online: https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/michigan/miedce/2:2013cv11544/279694/232/ (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Imad, Al-Din Ahmed, and Mohamed Abdou. 2021. Maritime Law of the United Arab Emirates, 1st ed. Sharjah: University of Sharjah. [Google Scholar]

- Kallem, Sreekanth Reddy. 2012. Artificial Intelligence Algorithms. Journal Of Computer Engineering 6: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamina, Pascal. 1996. L’utilisation Finale en Propriété Intellectuelle. Doctoral Dissertation, Université de Poitiers, Poitiers, France. [Google Scholar]

- Kingston, John K. C. 2016. Artificial Intelligence and Legal Liability. In Research and Development in Intelligent Systems XXXIII. SGAI 2016. Edited by M. Bramer and M. Petridis. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Ram Shankar Siva, and Frank Nagle. 2020. The Case for AI Insurance. Harvard Business Review Digital Article, April 29. [Google Scholar]

- Lachièze, Christophe. 2020. Intelligence Artificielle: Quel modèle de responsabilité? Dalloz IP/IT 12: 665. [Google Scholar]

- Latil, Arnaud. 2024. Droit de l’intelligence artificielle (droit international et droit européen). JurisClasseur Communication Fasc. 988: 6. [Google Scholar]

- LEI Packaging, LLC v. Emery Silfurtun Inc. 2015. LEI Packaging, LLC v. Emery Silfurten Incorporated et al, No. 0:2015cv02446 - Document 174 (D. Minn. 2017). Available online: https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/minnesota/mndce/0:2015cv02446/148896/174/ (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Lucas, A. 2001. La Responsabilité du Fait des Choses Immatérielles [Responsibility for the Fact of Immaterial Things]. In Études offertes à Pierre Catala. Le droit privé français à la fin du XXe siècle. Paris: Litec, pp. 817–826. [Google Scholar]

- Madison, Michael J. 2017. IP Things as Boundary Objects: The Case of the Copyright Work. Laws 6: 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, Rex. 2019. Artificial Intelligence: Distinguishing Between Types & Definitions. Nevada Law Journal 19: 1027. [Google Scholar]

- Matthias, Andreas. 2004. The responsibility gap: Ascribing responsibility for the actions of learning automata. Ethics and Information Technology 6: 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazeau, Laurène. 2018. Intelligence artificielle et responsabilité civile: Le cas des logiciels d’aide à la décision en matière médicale [Artificial intelligence and civil liability: The case of medical decision support software]. Revue Pratique de la Prospective et de L’innovation 1: 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Caminade, Alexandra. 2016. Le droit confronté à l’intelligence artificielle des robots: Vers l’émergence de nouveaux concepts juridiques? Recueil Dalloz 8: 445. [Google Scholar]

- Mizrahi, Charles. 2019. The Economic Impact of AI Projected To Be Over $14 Trillion. Available online: https://banyanhill.com/economic-impact-ai-14-trillion/ (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Nyholm, Sven, and Jilles Smids. 2016. The Ethics of Accident-Algorithms for Self-Driving Cars: An Applied Trolley Problem? Ethical Theory and Moral Practice 19: 1275–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payas v. Adventist Health Sys./Sunbelt, Inc. 2018. District Court of Appeal of Florida. Available online: https://law.justia.com/cases/florida/second-district-court-of-appeal/2018/16-3615.html (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Pélissier, A. 2001. Possession et Meubles Incorporels. Paris: s.l.:Dalloz-Sirey. [Google Scholar]

- Pierre, Philippe. 2023. Responsabilité civile et intelligence artificielle: Une proposition de directive européenne a minima? Responsabilité Civile et Assurances 1: 2. [Google Scholar]

- PwC. 2019. Gaining National Competitive Advantage Through Artificial Intelligence (AI). Available online: https://www.pwc.lu/en/advisory/digital-tech-impact/technology/gaining-national-competitive-advantage-through-ai.html (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Rebel, Christopher. 1995. The case for a federal trade secret act. Harvard Journal of Law & Technology 8: 427. [Google Scholar]

- Revet, Thierry. 2005. Propriété et droits réels. Revue Trimestrielle de Droit Civil 4: 807. [Google Scholar]

- Roubier, P. 1954. Le Droit de la Propriété Industrielle [Industrial Property law]. Paris: Sirey. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, Matthew U. 2016. Regulating Artificial Intelligence Systems: Risks, Challenges, Competencies, and Strategies. Harvard Journal of law & Technology 29: 354. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Szaleweski, Joanna, and Jean-Luc Pierre. 1974. Le droit du breveté entre la demande et la délivrance du titre. In Mélanges en l’honneur du Professeur Daniel Bastian. Paris: Librairie Techniques, p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- Sharjah Roads and Transport Authority v. Al-Futtaim Motors and Machinery. 2019. Federal Supreme Court, Case number: 585, UAE. January 22. [Google Scholar]

- Soyer, Baris, and Andrew Tettenborn. 2022. Artificial intelligence and civil liability—Do we need a new regime? International Journal of Law and Information Technology 30: 385–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekale, Komal Manohar, and Gowtham Reddy Enjam. 2024. AI Liability Insurance: Covering Algorithmic Decision-Making Risks. International Journal of AI, BigData, Computational and Management Studies 5: 151–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touzain, Antoine. 2023. Les perspectives liées à l’intelligence artificielle—Au titre des perspectives du droit des assurances au quart du XXIe siècle. Bulletin Juridique des Assurances 88: 2. [Google Scholar]

- Tricoire, Emmanuel. 2008. La responsabilité du fait des choses immatérielles [Responsibility for immaterial things]. In Mélanges en l’honneur de Philippe Le Tourneau. Paris: Dalloz, pp. 983–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Trout, Cristian. 2025. Insuring Uninsurable Risks from AI: Government as Insurer of Last Resort. Paper presented at Generative AI and Law Workshop at the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2024), Vienna, Austria, July 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- van Genderen, Robert H. 2018. Do We Need New Legal Personhood in the Age of Robots and AI? In Robotics, AI and the Future of Law. Singapore: Springer Publishers, pp. 15–50. [Google Scholar]

- Varošanec, Ida. 2022. On the path to the future: Mapping the notion oftransparency in the EU regulatory framework for AI. International Review of Law, Computers & Technology 36: 95–117. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, Gerhard. 2011. Custodian’s Liability in European Private Law. In Handbook of European Private Law. Edited by Jürgen Basedow, Klaus J. Hopt and Reinhard Zimmermann. Amsterdam: Elsevier. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1766138 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Wendehorst, Christiane. 2020. Strict Liability for AI and other Emerging Technologies. Journal of European Tort Law 11: 150–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendehorst, Christiane. 2022. Liability for Artificial Intelligence: The Need to Address Both Safety Risks and Fundamental Rights Risks. In The Cambridge Handbook of Responsible Artificial Intelligence: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Edited by Silja Voeneky, Philipp Kellmeyer, Oliver Mueller and Wolfram Burgard. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 187–209. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, John Frank. 2014. We Need to Pass Legislation on Artificial Intelligence Early and Often. Available online: https://slate.com/technology/2014/09/we-need-to-pass-artificial-intelligence-laws-early-and-often.html (accessed on 8 March 2024).

- Yanisky-Ravid, Shlomit, and Xiaoqiong (Jackie) Liu. 2018. When Artificial Intelligence Systems Produce Inventions: The 3A Era and an Alternative Model for Patent Law. Cardozo Law Review 39: 2215–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zech, Herbert. 2021. Liability for AI: Public Policy Considerations. ERA-Forum 22: 147–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | In accordance with general rules of contractual and civil liability, the US judiciary has rendered multiple rulings regarding liability for damage caused by artificial intelligence systems. These rulings cover issues such as factory liability for manufacturing defects or negligent maintenance, operator or owner liability for robot misuse, and user liability for improper or non-purpose operation. |

| 2 | “operator” means a provider, product manufacturer, deployer, authorized representative, importer or distributor, article 3, EU Artificial Intelligence Act. |

| 3 | Article 282 of the UAE Civil Transaction Code:” Any harm done to another shall render the actor, even though not a person of discretion, liable to make good the harm”. |

| 4 | The United Arab Emirates has launched a comprehensive National Artificial Intelligence Strategy 2031, which sets a clear vision to transform the country into a global leader in artificial intelligence by investing in key human capital and priority sectors. This strategy outlines objectives to build a fertile ecosystem for AI development, attract international collaboration, and support innovation within the UAE, thereby fostering an environment conducive to technological growth and practical implementation of AI solutions. https://teams.microsoft.com/l/message/19:61cbbe4f-6c5c-4624-9fa7-16a711a14828_9ede494f-50c3-47a7-ba55-44fb41fae952@unq.gbl.spaces/1766567598425?context=%7B%22contextType%22%3A%22chat%22%7D (accessed on 15 December 2025). |

| 5 | Article (1) of Federal Decree by Law No. (46) of 2021 on Electronic Transactions and Trust Services. |

| 6 | Article (1) of law No. (9) of 2023 Regulating the Operation of Autonomous Vehicles in the Emirate of Dubai. |

| 7 | Article (3/1) of Artificial Intelligence Act. |

| 8 | Article 1242, paragraph 1 of the Franche Civil Code: ”One is liable not only for damage caused by one’s own actions, but also for damage caused by the actions of persons for whom one is responsible, or by things in one’s care”. |

| 9 | Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 laying down harmonized rules on artificial intelligence and amending Regulations (EC) No 300/2008, (EU) No 167/2013, (EU) No 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, (EU) 2018/1139 and (EU) 2019/2144 and Directives 2014/90/EU, (EU) 2016/797 and (EU) 2020/1828 (Artificial Intelligence Act). |

| 10 | Paragraph (5) of Artificial Intelligence Act provides that: ”depending on the circumstances regarding its specific application, use, and level of technological development, AI may generate risks and cause harm to public interests and fundamental rights that are protected by Union law. Such harm might be material or immaterial, including physical, psychological, societal or economic harm”. |

| 11 | Article (5) of the Federal Decree-Law No. (48) of 2023 Regulating Insurance Activities. |

| 12 | Article (6) EU AI Act, Classification rules for high-risk AI systems. |

| 13 | aiSure™, Munich RE, Insure AI. https://www.munichre.com/en/solutions/for-industry-clients/insure-ai.html (accessed on 16 December 2025). |

| 14 | Article (27) of the Intelligent Robots Development and Distribution Promotion Act, No. 9014, 28 March 2008, Amended by Act No. 11690, 23 March 2013. |

| 15 | Article (7) of the Federal Decree-Law No. (48) of 2023 Regulating Insurance Activities. |

| 16 | See: Convention on Limitation of Liability for Maritime Claims (LLMC). URL: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%201456/volume-1456-I-24635-English.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abdou, M.M. Custodian of Autonomous AI Systems in the UAE: An Adapted Legal Framework. Laws 2026, 15, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws15010002

Abdou MM. Custodian of Autonomous AI Systems in the UAE: An Adapted Legal Framework. Laws. 2026; 15(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws15010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdou, Mohamed Morsi. 2026. "Custodian of Autonomous AI Systems in the UAE: An Adapted Legal Framework" Laws 15, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws15010002

APA StyleAbdou, M. M. (2026). Custodian of Autonomous AI Systems in the UAE: An Adapted Legal Framework. Laws, 15(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws15010002