1. Introduction

While separation and divorce are often assumed to mark the end of an abusive relationship, for many abused mothers, it triggers an escalating cycle of control and harm that continues long after the relationship has formally ended. Over the past two decades, scholars and practitioners have increasingly recognized the phenomenon of post-separation abuse—a persistent pattern of intimidation, coercion, and retaliation that frequently exploits legal and parental frameworks through repeated lawsuits, custody disputes, and strategic use of legal procedures (

Brownridge 2006, p. 516;

Hardesty et al. 2012, pp. 449–50;

Kelly et al. 2014, p. 5;

Jeffries 2016;

Spearman et al. 2024b, p. 2). Research has demonstrated how ex-partners weaponize legal systems intended to provide support, actively undermining abused mothers’ abilities to recover through tactics such as retaliatory custody filings, false allegations, and accusations of parental alienation (

Meier 2017;

Krigel and Hopenung Asulin 2022;

Gutowski and Goodman 2023b;

Spearman et al. 2024b;

Bradshaw et al. 2024;

Pears and Easteal 2025). Nevertheless, existing scholarship has only begun to explore how post-separation abused mothers experience and make sense of these processes, and how their evolving understandings of legality and justice themselves become entangled in the continuation of abuse. Such exploration is especially significant in light of radical feminist scholarship that argues that women’s experiences are often marginalized and that the law often reinforces power inequalities (

Schneider 2004, p. 239;

MacKinnon 2007, p. 41;

2017, p. 29).

As a contribution to this burgeoning effort, this study offers a rich phenomenological account of post-separation legal consciousness, namely, of how post-separation abused mothers understand, experience, and navigate the legal system that continues to bind them to their abusive ex-partner. Following a radical feminist perspective, situating post-separation abuse within broader gendered power relations, the first contribution of this inquiry is therefore phenomenological: Through in-depth interviews with 32 Israeli mothers co-parenting with abusive ex-partners and engaged in family court proceedings, we examine how encounters with the family law system shape mothers’ perceptions of justice, protection, and institutional authority. The Israeli context offers particular insights, as divorce proceedings operate under dual religious and civil legal systems, while litigants initially engage in mandatory dispute resolution processes that aim to facilitate early agreements and reduce adversarial litigation. When intimate partner violence is present, the law allows expedited access to court proceedings, yet victims frequently face institutional barriers, including mischaracterization of abuse as mutual conflict and systemic neglect of coercive control tactics (

Stark 2007, pp. 203–5;

Renan Barzilay and Youseri 2016;

Fitch and Easteal 2017;

Natalier 2018;

Krigel and Benjamin 2021, p. 1226;

Renan Barzilay et al. 2023;

Gutowski and Goodman 2023b, pp. 470–72;

Carline et al. 2024). In this context, this study contributes to existing work on legal consciousness by showing how disillusionment is not only a product of unmet expectations, but also a creative process—a mechanism through which abused mothers’ understanding of justice, legitimacy, and protection is fundamentally reshaped. Moreover, it demonstrates how contradictory legal orientations may function not only as sites of resistance but also as mechanisms that may sustain coercive control. This interpretation builds upon

Easteal et al.’s (

2019) and

Gutowski and Goodman’s (

2023a) findings on procedural injustice and institutional betrayal, offering a complementary perspective rooted in the lived experiences of post-separation abused mothers.

Our second contribution is analytical. Building on our phenomenological study, we identify distinct yet interconnected orientations that jointly comprise abused mothers’ dialectical legal consciousness: (a) Institutional Trust and Disillusionment, based in a belief that the law can provide safety, (b) Institutional Asymmetry, as mothers learn to “play by the rules” despite feeling compelled under conditions of asymmetrical power, and (c) Recognizing Entrapment, where abused mothers realize that legal processes, to which they are now bound, may perpetuate rather than interrupt coercive dynamics. Crucially, these contradictory orientations may unfold diachronically as cases progress, or exist synchronously as mothers navigate legal proceedings. Throughout this process, mothers describe feeling caught between the necessity of legal participation—to protect custody rights and financial security—and the realization that such participation exposes them and their children to continued harm.

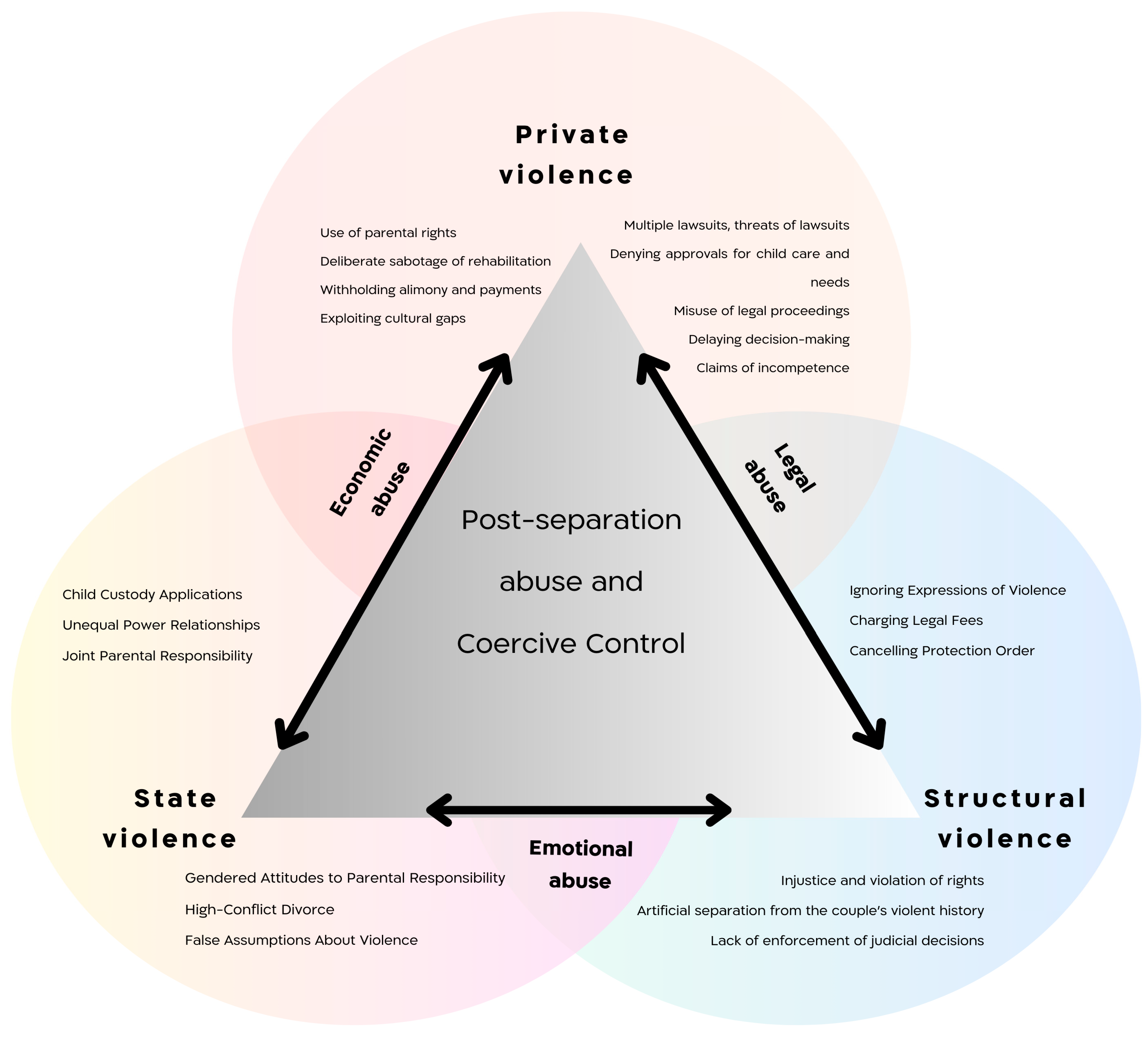

By informing our analysis with two theoretical frameworks, one concerning the Trias Violentiae framework, and the other concerning legal consciousness, emerges our last, conceptual contribution, which we denote through the notion of Entrapped Legal Consciousness. Post-separation abused mothers develop a paradoxical relationship with law—simultaneously seeking protection and distrusting the system that mandates continued contact with their abusers through custody arrangements, mediation requirements, and legal procedures. They thus understand themselves as trapped in a second-order abusive relationship through legal institutions, compelled to cooperate with processes they perceive as harmful yet unable to withdraw without risking greater harm. From the perspective of abused mothers, this dynamic enables the continuity of coercive control through legal institutions that they experience as reinforcing the very dynamics they sought to escape. Entrapped Legal Consciousness captures this perception of legality as a mechanism of continued constraint, extending legal consciousness theory by showing how contradictory orientations may effectively sustain, rather than break away from, continued control and established social relations.

These findings have crucial implications for the development of family law practices that acknowledge how legal proceedings may, from the perspective of abused mothers, inadvertently sustain rather than resolve patterns of coercion and harm. By tracing how legal processes are experienced by these women as reproducing rather than remedying post-separation abuse, this study contributes to ongoing calls for reforms that move beyond procedural fairness to address the substantive power asymmetries that legal formalism may obscure (

Schneider 2004;

Gutowski and Goodman 2020). Understanding how abused mothers perceive themselves as entrapped within legal institutions designed to help them is essential for designing interventions that are responsive to their lived experience in cycles of abuse.

1.1. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

This study draws on two complementary theoretical frameworks to examine how post-separation abused mothers experience and navigate family law proceedings. First, structural violence perspectives, including Schinkel’s (

Schinkel 2010;

Noordegraaf and Schinkel 2011, pp. 320–22) Trias Violentiae framework informed by a radical feminist perspective (

Schneider 2004;

MacKinnon 2007,

2017), illuminate how legal institutions can reproduce and legitimize power inequalities under the guise of fairness, and how they can reinforce gender-based structural inequalities. Second, legal consciousness theory explores how individuals understand, experience, and respond to law in their daily lives, revealing the dynamic relationship between institutional structures and individual interpretation (

Ewick and Silbey 1998;

Nielsen 2000;

Hull 2003;

Silbey 2005;

Chua and Engel 2019).

Together, these frameworks provide analytic purchase to examine how legal processes shape abused mothers’ understanding of justice and protection, and how these understandings themselves become entangled in the continuation of abuse. Emerging research suggests that victims’ legal consciousness is shaped through interactions with legal institutions, as they confront re-traumatization and the burden of proof in hostile legal environments (

Porter 2020;

Bierria and Lenz 2020). The frequent denial or minimization of abuse by courts constitutes a form of secondary victimization, damaging victims’ trust in legal institutions (

Schneider 2004;

Gutowski and Goodman 2020). This emergent body of work suggests we have still much to learn about how mothers experience, interpret, and navigate these legal processes, and how their evolving understandings of law become part of the dynamics they sought to escape. This study seeks to contribute to this effort through detailed phenomenological inquiry into post-separation legal consciousness.

1.2. Post-Separation Legal Proceedings

1.2.1. The Phenomenon of Post-Separation Abuse

Separation from an abusive partner presents a potential opportunity for recovery, yet this is rarely straightforward. For many abused mothers, separation triggers an escalation of control and harm that continues long after the relationship has formally ended. Over the past two decades, scholars and practitioners have increasingly recognized post-separation abuse—a persistent pattern of intimidation, coercion, and retaliation that frequently exploits legal and parental frameworks (

Brownridge 2006;

Hardesty et al. 2012;

Kelly et al. 2014;

Spearman et al. 2024b;

Avieli 2025). This abuse includes stalking, financial manipulation, reputational attacks, and harassment through legal channels such as repeated lawsuits and custody disputes. These tactics reflect not merely individual persistence, but a systematic strategy to undermine mothers’ autonomy and safety, often exploiting the legal and parental frameworks that remain in place post-separation (

Bierria and Lenz 2020;

Katz et al. 2020;

Porter 2020;

Gezinski and Gonzalez-Pons 2022;

Gutowski and Goodman 2020,

2023a,

2023b;

Hay et al. 2023;

Spearman et al. 2024a;

Carline et al. 2024;

Bradshaw et al. 2024;

Wilde et al. 2024).

Post-separation abuse can be difficult to identify, particularly when its forms are less overt than physical violence. Key indicators include the abuser’s misuse of legal processes (such as repeated filings or false claims), weaponization of child custody and visitation arrangements, and persistent economic control (

Jeffries 2016;

Meier 2017;

Katz 2022;

Krigel and Hopenung Asulin 2022;

Gutowski and Goodman 2023a;

Avieli 2024). These behaviors often escape formal recognition, as they are masked by the language of rights, shared parenting, and procedural fairness (

Easteal et al. 2019, pp. 14–15). Common tactics include retaliatory custody filings in response to protection orders, false allegations, and accusations of parental alienation or incompetence (

Spearman et al. 2024b). Specifically, the call for “parental alienation” has been increasingly recognized as a discursive strategy used especially by men accused of violence or abusive behavior, as a way to attack women’s credibility and maintain control through the legal system (

Meier 2020;

Barnett 2024), even as others have contested such assertions (

Marcus 2020, p. 548;

Bernet 2020;

Bala et al. 2024, p. 944).

While the phenomenon of post-separation abuse is widely recognized in international research, the Israeli case offers a particularly instructive lens through which to examine the role of legal institutions in sustaining gendered power dynamics. Israel’s dual legal system, comprising both civil and religious family courts, operates within a broader cultural and institutional context in which gendered assumptions about parenting, authority, and legitimacy are deeply embedded (

Bogoch and Halperin-Kaddari 2006). This structural duality creates a legal environment that may amplify tensions between formal protections and normative expectations, especially for abused mothers seeking safety and recognition.

1.2.2. Legal System Responses and Limitations

Abusive ex-partners often exploit legal systems intended to provide support, actively undermining the abused mother’s ability to recover. As a result, many abused mothers describe their legal experiences as a form of institutional or “judicial betrayal”—a systemic denial or minimization of the abuse (

Gutowski and Goodman 2023a;

Spearman et al. 2024a;

Carline et al. 2024). While existing literature has often framed legal institutions as external mediators of first-order abuse—violence enacted directly by the abusive partner, this study points to a deeper entanglement. This study introduces the concept of second-order abuse to describe how legal processes themselves may come to be experienced by abused women as a continuation of coercive control. While first-order abuse refers to the interpersonal violence enacted by the ex-partner, second-order abuse captures moments in which the legal system—through court decisions, procedural asymmetries, or failures of enforcement is perceived as replicating, legitimizing, or amplifying the dynamics of power and fear that characterized the abusive relationship. This distinction highlights how abused mothers come to see the legal process not merely as ineffective, but as complicit in sustaining the very harms it was meant to remedy. This experience of institutional reconfiguration of abuse demonstrates how legal consciousness mediates the movement of violence across private, structural, and state domains. In doing so, the study offers an empirical application of the Trias Violentae framework, revealing how legality can become a pathway to sustaining coercive power under institutional protection.

1.2.3. Institutional Barriers and “High-Conflict” Framing

Post-separation abused mothers, particularly in high-conflict divorces, frequently face institutional barriers. When post-separation abuse is interpreted as “high-conflict” divorce, rather than involving asymmetrical violence and coercive control behaviors, these presumptions can result in court orders that mandate continued interaction between abused mothers and their abusive ex-partners through custody exchanges, joint decision-making requirements, and shared parenting responsibilities (

Humphreys and Thiara 2003;

Stark 2007;

Krigel and Benjamin 2021).

Institutionally, there is a prevailing assumption that once separation occurs, the violence ends, and children are no longer exposed (

Brownridge 2006;

Spearman et al. 2024a, p. 197). In a longitudinal study of post-separation legal abuse,

Gutowski and Goodman (

2023a) found that in approximately 30% of cases, the level of violence did not diminish over time, and in nearly 80% of cases, victims reported continued harm—emotional, functional, and economic—long after the separation. Continued exposure to violence, trauma, and fear places both mothers and children at further risk (

Gezinski and Gonzalez-Pons 2022;

Krigel and Hopenung Asulin 2022;

Hay et al. 2023).

1.2.4. Structural Analysis: Legality as a Site of Power Reproduction

These empirical findings align with broader theoretical insights about legality’s role in reproducing structural inequalities. Schinkel’s (

Schinkel 2010;

Noordegraaf and Schinkel 2011;

Schinkel 2013) Trias Violentiae framework offers a conceptual model for analyzing the movement between three interrelated forms of violence—private, structural, and state—and the ways in which each may disguise itself as another. In the context of post-separation abuse, the harm experienced by abused mothers is a byproduct of legal norms and procedures that fail to account for the ongoing nature of coercive control. While prior research focused on how legal processes may overlook coercive dynamics (

Stark 2007;

Bierria and Lenz 2020), less attention has been paid to how such processes might participate in an institutional reconfiguration of violence across multiple levels.

Radical feminist theory, particularly

MacKinnon (

2007) and

Schneider (

2004), reinforces this view by analyzing how law institutionalizes gendered power through the systematic distribution of resources, authority, and credibility. Legal systems are not neutral arbiters, but rather mechanisms that organize social hierarchies and maintain gendered forms of control—especially in cases of intimate partner violence. Feminist legal scholars argue that the “personal is political,” (

Schneider 2004;

MacKinnon 2007) and that legal responses to abuse reflect structural gender inequalities rather than merely individual disputes (

MacKinnon 2007,

2017).

1.3. Legal Consciousness

Legal consciousness scholarship examines how individuals other than legal professionals perceive, experience, and respond to law in their daily lives (

Ewick and Silbey 1998). Rather than viewing law as external to everyday experience, this framework explores how people actively interpret and make sense of legal encounters, revealing the dynamic relationship between institutional structures and individual understandings. As originally articulated, the theory identifies three dominant orientations or “schemas”: before the law, in which law is seen as authoritative but remote (p. 83); with the law, where law is viewed as a strategic tool to navigate or manipulate (p. 131); and against the law, where individuals perceive the legal system as harmful or inaccessible, leading them to resist or avoid legal engagement (p. 188).

Subsequent scholarship has critiqued and refined this framework to emphasize the relational, fluid and at times contradictory dynamics of legal consciousness (

Abrego 2008, pp. 727–31;

Chua and Engel 2019).

Nielsen (

2000, pp. 1086–89) and

Hull (

2003, pp. 654–55) demonstrated that individuals often move fluidly between schemas, sometimes within a single legal encounter, rather than maintaining fixed orientations.

Levine and Mellema (

2001) showed how people can simultaneously hold contradictory understandings of law, experiencing it as both protective and threatening. More recent work by

Young (

2014) and

Abrego (

2018, pp. 198–200) emphasizes the contextual, relational, and even collective dynamics of legal consciousness as shaped through institutional encounters rather than stable individual orientations.

Hefner et al. (

2022) found that when the asymmetry of power between an abusive ex-partner and the abused mother is reinforced by the manner in which the legal system operates, the mothers’ willingness to see the law as a tool for achieving justice diminishes (

Hefner et al. 2022, p. 1387). This evolving understanding highlights legal consciousness as a dynamic, multifaceted phenomenon, particularly relevant for understanding how abused mothers navigate complex and prolonged legal proceedings in post-separation contexts.

Post-Separation Legal Consciousness

The phenomenological focus of legal consciousness literature can offer several insights for understanding post-separation abuse. First, it may help capture how abused mothers’ understanding of legality emerges through lived experience rather than abstract legal doctrine. This approach reveals how encounters with family law proceedings shape their perceptions of justice, protection, and institutional authority in ways that may not align with formal institutional goals.

Second, the framework foregrounds the links between individual perception and institutional structural dynamics through the concept of legal hegemony (

Silbey 2005). Silbey argues that legal institutions reproduce inequality not through explicit coercion, but through routinized decision-making scripts that become culturally embedded and invisible. Legal consciousness is thus shaped by social context and power relations, reinforcing unequal structures even as law purports to ensure justice and objectivity (

Ewick 2009;

Silbey 2005). This insight aligns with structural violence perspectives, particularly Schinkel’s analysis of how violence moves between private, institutional, and state forms through seemingly neutral mechanisms. Similarly,

MacKinnon’s (

2017) critique of law’s claimed neutrality reveals how legal processes can systematically disadvantage already marginalized groups while maintaining an appearance of fairness. The integration of legal consciousness theory with structural violence frameworks thus reveals how individual interpretations of legality—even and perhaps especially when they reveal internal tensions and contradictions—can become mechanisms through which power relations are reproduced.

Third, more recent scholarship on legal consciousness discusses contradictions and paradoxes in how people relate to law. Rather than assuming consistent schemes or orientations, this body of work recognizes that individuals may simultaneously hold multiple, even conflicting, understandings of legal authority (

Nielsen 2000;

Ewick 2009;

Young 2014). Yet such relational and dynamic understandings of legal consciousness should not be romanticized. As Chua and Engel caution (

Chua and Engel 2019, p. 345):

To the extent that individual personhood is subsumed within other social relationships, there is a possibility that these relationships are unequal and maintain existing social hierarchies. Certain forms of relational consciousness may normalize the plight of an abused spouse or an exploited laborer.

In the context of post-separation, abused mothers may shift between or simultaneously experience different orientations toward legality as their legal experiences unfold, yet these contradictions may themselves become mechanisms of control.

Spearman et al. (

2024a) explored how legal consciousness, legal mobilization, intersectionality, and relative power can explain survivor decision-making. Their findings revealed that survivors frequently explain how they had adapted their survival strategies to account for how the legal system operated in their everyday lives (

Spearman et al. 2024a, p. 196). This relational framework recognizes that individuals actively interpret legal experiences and make strategic choices within circumstances of constraint—choices that may help them navigate impossible realities but might also reinforce the dynamics they seek to escape. This perspective is crucial for understanding how post-separation abused mothers navigate legal systems—not as passive victims of institutional failure, but as active interpreters who develop complex understandings of how legality functions in their lives, understandings that may themselves become entangled in cycles of ongoing abuse.

This theoretical integration provides the analytical framework for examining how post-separation abused mothers’ legal consciousness takes shape through their encounters with family law proceedings, and how these understandings themselves become part of the dynamics of ongoing abuse. Accordingly, this study employs a relational conception of legal consciousness to explore distinct and at times contradictory orientations, while considering how these operate through and within asymmetrical institutional dynamics. While existing scholarship has begun to document conflicting orientations, we are yet to fully understand how these contradictions might function not only as strategies of survival and resistance but also, possibly, as mechanisms that perpetuate rather than disrupt coercive control.

The Israeli family law context, with its unique institutional features, provides a particularly generative setting for exploring these dynamics. This institutional landscape is crucial for understanding the experiences, understandings, and orientations of post-separation abused mothers. Indeed as

Ewick and Silbey (

2003) emphasize, legal consciousness is not a free-floating analytic object that can be studied in isolation; it is rather always rooted in, and shaped by material and symbolic conditions and contingent institutional arrangements. The particular features of the Israeli family law system—mandatory mediation mechanisms, dual legal frameworks, civil protection mechanisms, and presumptions toward shared parenting (

Krigel and Hopenung Asulin 2022;

Hacker and Ladani 2023;

Avieli 2024), provide a compelling context for examining how legal institutions intended to protect can inadvertently become mechanisms through which control and abuse continue. At the same time, this context offers insights that extend beyond the Israeli case to other legal systems grappling with similar tensions between protecting victims and maintaining procedural fairness.

2. Methods

2.1. Methodological Approach

To explore the intricacies of post-separation legal consciousness among abused mothers, we employed an Interpretative Phenomenological–Hermeneutic approach, emphasizing the understanding of lived experience within broader legal, social, and institutional contexts (

Smith 2011, p. 10). This Double Hermeneutic lens enabled us to interpret how victims of ongoing post-separation abuse made sense of their encounters with the family law system, and how their legal consciousness was shaped through these interactions. This approach is particularly suited to our framework: illuminating the dynamic interplay between institutional practices and abused mothers’ subjective experiences of power, vulnerability, and resistance within legal proceedings (

Neubauer et al. 2019, p. 94).

2.2. Data Collection

After receiving IRB approval, we conducted thirty-two in-depth, semi-structured interviews, each lasting about 90 min, with mothers who met the following criteria: (1) they had experienced violence before, during, and after separation; (2) they were co-parenting with the abusive ex-partner; (3) they had been involved in family law legal proceedings; and (4) they had been divorced for at least two years, during which abuse continued. Participants were recruited through purposive heterogeneous sampling to ensure diversity (

Patton 2014, p. 423) across geographic (urban, rural), cultural (secular, religious) and legal domains (family courts, religious courts, appellate courts), as described in

Appendix A.

We used social network communities to find participants, and each participant completed an online anonymous questionnaire to verify her suitability for the research. Afterwards, we scheduled a phone call between the researcher and the interviewee to thoroughly explain the purpose and potential risks of participating, and we obtained written consent. The interviews were designed to gather open, narrative-driven accounts of participants’ experiences with legal processes, aiming to create opportunities for respondents to share diverse experiences and interpretations (

Ewick and Silbey 2003, p. 1339). Each interview was double-recorded on video and audio.

2.3. Data Analysis

Data analysis followed Braun and Clarke’s (

Braun and Clarke 2006,

2022) six-phase reflexive thematic analysis approach, with a constructivist and latent perspective, integrating both semantic and latent levels of interpretation. At first, we transcribed each interview recording after re-watching it, and visual characteristics were noted and incorporated as needed. Initial coding was performed inductively, identifying recurring expressions, contradictions, and emotional tones in participants’ narratives about their post-separation legal experiences (

Ewick and Silbey 2003;

Braun and Clarke 2006). In phases three and four—searching for themes and reviewing themes—coded segments were examined for conceptual links and contradictions, then organized into central themes, subthemes, and thematic maps (

Terry et al. 2017, pp. 27–30). The analysis was recursive, allowing revisiting earlier stages to improve alignment and clarity (

Braun and Clarke 2022, pp. 8–10). For example, fear was initially coded under “Daily coping with post-separation abuse,” but further analysis revealed that it stemmed not only from the abuser but also from legal encounters, prompting a reclassification under “Post-divorce fear: Control changes form, but power remains.”

In phase five—defining and naming themes—each theme was refined to clearly represent its narrative contribution, boundaries, and relation to the research question (

Braun and Clarke 2006, p. 22). Reflexivity played a key role in ensuring authenticity to participants’ voices while distinguishing between overlapping meanings (e.g., between “fear” and “lack of protection”). In phase six—producing the report—themes were contextualized within legal consciousness theory (

Ewick and Silbey 1998) to illustrate how participants’ shifting positions reflect broader dynamics of institutional power, legal hegemony, and justice denial (

Ewick and Silbey 2003;

Silbey 2005). Analysis was conducted iteratively, in conversation with the theoretical frameworks of legal consciousness and the Trias Violentae framework, highlighting how individual experiences reflected broader structures of hegemonic legal power.

The interpretive nature of this research, along with the choice of reflexive thematic analysis, highlighted a methodological approach that emphasizes reflexivity and the collaborative pursuit of analytical depth over inter-rater reliability (

Braun and Clarke 2022). Consistent with this approach, coding was performed by the first author in iterative dialog with the other authors and the relevant literature. All stages of coding, like other parts of the analysis, involved ongoing discussion among the authors, with each stage reviewed separately, aiming to maximize analytical depth as well as to minimize biases. Reflexivity was maintained throughout via analytic memos and feedback among researchers, ensuring that theoretical insights were grounded in the abused mothers’ lived experiences while remaining critically attentive to researchers’ positionality.

2.4. Limitations

One limitation of this study lies in the retrospective nature of the narratives, which reflect participants’ current meaning-making processes rather than offering direct access to real-time events or changes over time. These accounts are shaped by the moment of telling and the relational and institutional contexts in which they are told. As such, the data does not allow for causal inferences or demonstrable links to broader structural processes. However, this interpretive approach offers rich insight into how abused mothers reflexively construct meaning out of past and ongoing experiences and navigate post-separation violence through situated and dynamic forms of legal consciousness.

Another limitation of this study relates to our phenomenological-interpretive research approach, which centers on subjective experiences and perceptions. This study focuses specifically on how abused mothers experience their encounters with the family court system rather than evaluating the objective performance of legal decision-making processes. We acknowledge the inherent limitations of subjective perception and memory, as well as participants’ constrained ability to verify information. These constraints are amplified by Israel’s practice of not publishing family court rulings by name, to preserve parties’ privacy. Recognizing these methodological considerations, we interviewed over 30 Israeli post-separation abused mothers to enhance the reliability of findings within our interpretive framework.

While the study generated rich, nuanced data, certain themes—such as parental alienation used as a form of legal abuse—emerged but could not be fully explored within the current scope. These aspects may be addressed in future publications.

3. Findings

This section presents the core findings of the study, organized analytically around three orientations that emerged from the interviews: Institutional Trust and Disillusionment, Institutional Asymmetry, and Recognizing Entrapment. These orientations offer a framework for understanding how post-separation abused mothers navigate and interpret their interactions with the family law system in the years after separation. The first orientation, Institutional Trust and Disillusionment, emerges from a hope that the legal system will provide protection and recognition; the second orientation, Institutional Asymmetry, reflects an understanding of the legal systems as unequal; and the third orientation, Recognizing Entrapment, marks a critical awareness of the system’s role in reproducing coercive dynamics. Together, they expose the ways in which abused mothers navigate legal terrain not as passive recipients of justice, but as active interpreters of its limits and contradictions. Their legal consciousness is not static—it is adaptive, responsive, and at times resigned, but rarely detached.

Findings describe how abused mothers perceive and interpret their encounters with the family law system, often revealing a painful gap between the law’s protective promise and how the abused mothers experience and make sense of its lived outcomes. Drawing on their narratives, the analysis traces the shifting contours of legal consciousness as it evolves under conditions of structural constraint and ongoing legal abuse and other types of coercive control by the ex-partner. These orientations illustrate how legal consciousness is shaped within and through the legal system, revealing it as a mechanism that enables the continuity of violence. This framework culminates in the concept of entrapped legal consciousness, which captures how legal norms and procedures may sustain coercive control across private, structural, and state domains.

3.1. Institutional Trust and Disillusionment

As abused mothers emerge from abusive relationships and enter the legal system in search of protection, their experiences reveal how private violence is not dismantled by legal intervention, but rather reframed through institutional mechanisms. While some participants initially articulated hope, expecting the legal system to act upon their testimony or prioritize their children’s safety, the abused mothers did not describe this hope as rooted in emotional trust, but rather in a culturally embedded narrative that framed the court as the appropriate venue for protection. As

Ewick and Silbey (

2003) note, individuals often construct their legal narratives in ways that conform to dominant schemas, even when these schemas later prove incompatible with their lived realities. In this way, the initial disposition of trust reflects less a psychological state and more a socialized position vis-à-vis the legality—one that presumes accessibility, fairness, and authority. As participant 17 shared: “

I thought once the divorce was finalized, I’d finally be free. But now I have to keep seeing him in court, negotiating with someone who spent years threatening me—and the judge keeps saying we both need to compromise.” (P17)

Over time and repeated exposure to legal procedures, participants described a growing realization that the system failed to offer the protection it promised. As Participant 2 explained: “There is a very great disappointment in the understanding that there is no justice in the courtroom. Very disappointing. It’s very disappointing that there are people out there who come out of the water dry.” (P2)

When testimonies were dismissed, protection orders denied, or the violence reframed as mutual high conflict divorce, participants described a sense of confusion, isolation, and feeling of betrayal. Participant 48 describes the fear of trusting the legal system when she says:

I can’t trust anyone who doesn’t believe me, my story and what I’m experiencing. I can’t trust! It’s really become a situation of—either you’re with me or you’re against me. All of life has become a court. About everything. So my whole life is now a legal proceeding.

(P48)

This disorientation was not only emotional. It marked a cognitive rupture that began to reshape how they interpreted the role of legality in their lives. In the absence of validation, they began to question not only the system’s ability to protect them, but also its willingness to even recognize their experiences as legitimate. As

Gutowski and Goodman (

2020) argue, legal responses that ignore the gendered dynamics of control and coercion can retraumatize the abused mothers, exacerbating their sense of vulnerability and undermining trust. Within this shifting legal consciousness, trust becomes a fleeting phase, undone by a sense of the system’s failure to uphold its own promises. Participant 54 talks about how she experienced the judge’s treatment of her attempt to rebuild her life under the economic abuse she has been experiencing from her ex-partner:

So… I lost everything. I was left with nothing, not even the confidence to tell my daughters that they would have an inheritance. I have nothing to give them really, I don’t have any. (…) and all the judge had to say to me was: ‘What do you want to say? I saw you wrote that in the lawsuit. So what?’ so I said to her, ‘I want to live.’

(P54)

Building on

Gutowski and Goodman’s (

2020,

2023a) findings regarding the centrality of procedural justice and validation for survivors of post-separation abuse, this study complicates the assumption that recognition alone is sufficient to restore institutional trust. While prior research has shown that validation of the abuse, through acknowledgement in court decisions, protective orders, or judicial language, can play a crucial role in mothers’ psychological recovery, the narratives in this study reveal a more fragile and ambivalent dynamic. Several participants described moments in which the court acknowledged the abuse, either explicitly or implicitly, yet failed to provide concrete protection or enforce existing decisions. In these cases, the gap between symbolic validation and material protection created a heightened sense of abandonment and risk. As Participant 5 shared:

He did not comply with any legal decision. (…) he simply did what he wanted and took the children, or did not take the children, and eventually when I asked for sanctions for that, the judge said: ‘Even if you agree on sanctions among yourselves, I will not approve it.’

(P5)

These accounts complicate existing findings on the importance of validation within legal processes. While prior studies have emphasized the psychological and relational importance of being recognized and validated by the court (

Gutowski and Goodman 2020;

Bradshaw et al. 2024;

Pears and Easteal 2025), participants in this study highlighted how such recognition, when not accompanied by concrete protective outcomes, could deepen feelings of second-order abuse. Participant 21, who had sought a restraining order, described how the judge refused her request and ordered her to pay legal fees: “

After I told her everything, and cried to her, she didn’t give him a restraining order, and I also received a thousand shekels in legal expenses.” (P21). This experience was often described as an experience of institutional reconfiguration, as Participant 7 noted: “

Just the fact that you’re coming and telling the court about the abuse—that already leads to more abuse.” (P7).

In their view, being believed but left unprotected intensified the sense of legal abandonment, especially when abusive ex-partners retained access or control through legal proceedings. As participant 18 described the despair of being forced to return to the same judge, despite having no confidence in the system: “

Applying to court again is something that is very, very distrustful from my perspective.” (P18). The turning point was often the denial or neglect of their requests for concrete protection. as Participant 5 explained:

There were moments when I asked: How can they not see this? How can they not see what I am going through? What my children are going through? There is a conflict, they say—but I feel silenced. And I think that this blindness is ignoring a crime. A real crime.

(P5)

These experiences suggest that for some post-separation abused mothers, validation alone may not be sufficient to foster renewed trust or gain safety within the legal system. At this point, abused mothers are expected to comply with legal decisions—such as mediation or contact with the abuser—despite knowing that these processes are ineffective or harmful (

Douglas 2018;

Stoever 2019, p. 198;

Easteal et al. 2019;

Stark 2020, p. 40).

Notably, the feeling of being exposed and endangered by legal processes themselves emerges clearly: “Not only do they not address the violence, they increase the violence,” said Participant 46. “Not only do they not protect the weak, they expose them even more to danger!” (P46). Simularly, participants 10 and 24 described separately how their application for a protection order was dismissed, and their abuser’s gun license reinstated—an outcome each of them experienced as both frightening and deeply disorienting. In such moments, what emerges is not only disillusionment with the legal system, but a transformative shift in legal consciousness, where legality is no longer seen as a neutral arbiter, but as a space of risk and exposure.

3.2. Institutional Asymmetry

Following their initial disillusionment, many abused mothers who participated in this study did not retreat from the legal process but rather remained bound to it—convinced that non-participation would endanger their rights, reputation, or the wellbeing of their children. This legal expectation is often justified through appeals to procedural neutrality, equality between parents, and the best interest of the child (

Hacker and Ladani 2023). Yet, as

Ewick and Silbey (

2003) argue, the law’s claim to neutrality is always embedded in a broader cultural and institutional context, one that shapes how legal actors interpret conflict and assign responsibility. What appears to be neutral from a formal standpoint may, in practice, reflect and reproduce the very inequalities it purports to remedy. As

Durfee (

2021) claims, the process by which this occurs may not be intentional, and often occurs when institutions make inappropriate assumptions about the individuals who work in or come into contact with those institutions (

Durfee 2021, 651). Court decisions are perceived as unequally enforced: violations by abusive ex-partners often go unaddressed, while abused mothers feel they are held to stricter standards of cooperation, civility, and parental availability. Participant 54 feels bound and helpless in the face of the lack of enforcement in daily economic coping, when she finds herself each month late in payments depending on her ex-partner’s decision whether and when to transfer child support payments to her as determined by the court’s decision: “

He lives his life, he does whatever he wants, whenever he wants. I’m stuck. I can’t do what I want to the extent of going out to work. I can’t.” (P54).

The experience of being limited by court decisions, as participants described how they feel as if legal instruments—such as salary foreclosure, travel restrictions or residency requirements—can be mobilized against them, even though they are the ones whose rights have been violated. Participant 44, who is involved in a cross-border divorce case involving assets outside of the country, said:

I can’t leave the city I’m in. There was a point where I think they came to my employer to foreclosure my salary so they could get money from me. It’s total control. You feel trapped. I can be like others I know—completely stuck in this country, never able to leave.

(P44)

Such cases resonate with emerging research on the legal entanglement of international divorce, especially when relocation or jurisdictional complexities make abused mothers more vulnerable to manipulation through technicalities and institutional inertia. For abused mothers, the line between legal coercion and structural violence is increasingly blurred, as legality itself is experienced as an extension of coercive control, reconfiguring in legal terms.

Avieli (

2024) shows that even when the abusive ex-partner is convicted and incarcerated, abused mothers are still forced to settle with the abuser over financial and parental matters, as he gets to use his legal rights to maintain his control over her life (

Avieli 2024, pp. 4–5). The coercion, as experienced by post-separation abused mothers, was not only material, but psychological: they learned that even protective orders were meaningless if the system continued to enforce contact. “

I had both a restraining order and a protective order—and they still told me it was my responsibility to take the girls to see him, or I would break the visitation agreement.” (P7). In one striking example, Participant 10 expressed concern upon learning that her ex-partner, despite a criminal conviction in a separate case, had his gun license reinstated: “

And now he has his gun license back.” (P10). Similarly, Participant 14 recounted the outcome of the court hearing in which her request for a protective order was denied: “

The end of the hearing was: the protective order was revoked, his gun returned, and legal fees were imposed on me.” (P14). That is the moment when legal consciousness is no longer shaped by disappointment alone, but by the realization that legality itself may deepen vulnerability through its formal authority.

Participants described how decisions made by the courts not only ignore the threat of ongoing abuse, but in some cases re-enable it. In this context, abused mothers’ legal consciousness adapts itself to the rules and norms of the system. They do not express agreement with legal expectations, but rather describe a form of compliance grounded in risk management—a strategy of self-protection rather than trust. As one woman explained, complying with contact orders or mediation referrals was not about believing the system would protect her, but about avoiding outcomes she feared would be worse. This sense of limited choice resonates with what participants describe as institutional asymmetry—the belief that their experiences of abuse are minimized or mischaracterized, while their own actions are closely scrutinized and sanctioned.

Porter (

2020) and

Douglas (

2018) highlight how such performative cooperation is not merely behavioral, but also deeply emotional: abused mothers learn to suppress legitimate fear and anger in order to meet gendered demands for civility, reasonableness, and co-parenting harmony. Similarly, scholars like

Stoever (

2019) and Spearman (

Spearman et al. 2024b) have shown that the family law system often rewards procedural compliance over substantive safety, shifting the burden of stability onto mothers, even when such expectations expose them to further harm.

The experience of abused women in this study highlights how legal mechanisms, designed to be neutral and protective, may be perceived as reconfiguring rather than mitigating the dynamics of coercive control. The abused mothers understand that the mediation process is not the appropriate solution for dealing with the violent spouse, but accept the court’s choice to refer them to mediation, with all that this implies, as is evident from the description of participant 10:

Yes, so I went to mediation and at some point I realized that there was a sword hanging over my neck. Because of the economic abuse I was dealing with I couldn’t pay the grocery store or the electric company and he was willing to continue this mediation process indefinitely and I also saw that he was managing to spin that lawyer who conducted the mediation.

(P10)

Abused mothers recognize that non-compliance may result in harsher outcomes: financial penalties, legal accusations of non-cooperation and even loss of custody. This internalized understanding of “how the system works” led to a reluctant, yet strategic, form of compliance. These findings echo critiques by feminist legal scholars, including

Katz’s (

2022) work on post-separation abuse, and

Easteal et al.’s (

2019) analysis of how coercive legal procedures can be used. However, this study adds a critical insight: the legal consciousness of abused mothers is itself shaped by this misrecognition, creating a patterned understanding that compliance is the only viable way to avoid further harm—despite the knowledge that compliance perpetuates their subordination. Participant 27 shares:

I withdrew the lawsuit because later in the hearing the judge “offered” me again. She stopped the hearing and said to me, ‘If we continue, I don’t think I will rule in your favor, I recommend that you withdraw the lawsuit.’ So I tearfully withdrew the lawsuit. I should also have said thank you for not charging me legal fees. I’m just sitting there, not standing up for my rights, not suing for anything.

(P27)

From the abused mothers’ perspective, this may be more than a manipulation of legal tools by the abuser, but also a structural phenomenon of second-order abuse where formal processes, decisions, and routines facilitate the continuation of power asymmetries through institutional design.

In this orientation, legal consciousness is shaped not by faith in justice but by an awareness of how institutional norms are perceived to reflect and legitimize unequal burdens. Within this legal consciousness, women describe navigating a system they experience as formally neutral yet practically unbalanced. What participants experienced was not a neutral system, but one that imposed demands under the guise of fairness, while overlooking their past victimization and ongoing vulnerability. This asymmetry, when internalized, shaped a legal consciousness attuned to risk and silencing, where compliance was not strategic but coerced by institutional norms. Compliance becomes a tactic—not a sign of acceptance, but a necessary adaptation to navigate a system they experience as simultaneously demanding and indifferent.

The accounts of participants in this study illustrate how legal consciousness becomes a strategic tool of self-preservation under conditions of institutional asymmetry. While seeking protection and justice, post-separation abused mothers found themselves increasingly entrapped, expected to participate in legal processes that both mirrored and legitimized the coercive dynamics they sought to escape.

3.3. Recognizing Entrapment

The third orientation reflects a shift in which legality is no longer viewed as an imperfect yet necessary resource, but as a system that reinforces, legitimizes, or reactivates the very power relations they sought to leave behind.

This experience was often described as an experience of double jeopardy: being bound by the law and abandoned at the same time, as one participant put it. From their perspective, the legal system of family law thus becomes a space in which abused mothers internalize a logic of limited choice: one in which they must comply with legal demands, however unsatisfactory, or repeat the trauma, in order to avoid even greater risks. Their legal consciousness, shaped by these conditions, reflects a strategic adaptation to institutional expectations—a mode of survival that reflects the control they previously endured in the private sphere. Participant 14 expresses fear when she seeks help for the distress she experiences due to the ongoing violence and the legal system’s response to it when describing this entrapment, she finds herself in:

I am in some kind of circle that you are trapped in. On the one hand, it is as if you are trying to function for the children, on the other hand, you understand that for the children you need to slow down, and on the third, if you dare to turn to the system and say I am under terror and I am in mental distress, they will tell you that you are unfit to parent.

(P14)

This entrapment reveals how movement between private spheres of violence and structural or state spheres of violence is made possible by legal mechanisms. Participant 48 tells about her difficult experience when she was asked to reveal the details of her financial conduct, at the request of the judge, even during a period that was not relevant to the hearing of the application and said: “I was really scared! Because it’s all your bank statements, it’s all your credit details from three years ago, all your expenses! Everything! And it’s like revealing… I just felt naked.” (P48).

As the ex-partner’s violent history and the need for ongoing control are either ignored or being recognized without concrete protective outcomes and enforcement, the abused mothers experience the court’s response as it legitimizes the disconnection from the supportive environment, while affecting the children in the process. Participant 23 describes it in her own words:

Guilt means that there are two guilty parties, but they don’t look at the other party who is guilty, they only look at me (…) There is nothing else, nothing interests them, they are busy with a fight between spouses, a high-intensity conflict, and that the father should see the children.

(P23)

The recurring presence of legal mechanisms, such as custody arrangements, visitation rulings, and mandatory mediation, as tools for post-separation control echoes

Jeffries (

2016) and Katz’s (

Katz et al. 2020;

2022) analysis of domestic abuse through child contact, in which the parental sphere becomes a site of continued coercion. As Participant 36 painfully observed, “

An abusive man knows that a child is everything to a mother—and that is where he hits the hardest.” This realization reframes legal interventions not as neutral or protective, but as complicit extensions of private violence cloaked in institutional legitimacy. However, this study extends their work by showing how family law proceedings themselves—often under the framing of promoting the “best interests of the child”—serve as a fertile ground for the continuation of coercion. Participant 43 tells of a case in which she tried to involve the social worker in the legal proceedings accompanying the case because she experienced ongoing violence from her ex-partner who used shared parenting “at the expense” of the child’s welfare, just to maintain the relationship of control: “

I told her (the social worker), ‘But I’m being abused! The fact that he has power over her means he has power over me. She’s like a hostage and I have to do what he tells me.’” (P43), and participant 18 painfully expresses the experience in which she feels that the legal system does not attach importance to harming children due to the use of parental space to preserve violence: “

There are children here who are often helpless in the face of this and in the face of the parents’ rights to actually meet and see them. It’s as if there is too much tolerance for violence in the courts.” (P18).

These experiences demonstrate what

Spearman et al. (

2024b) terms the weaponization of legal process. In this context, abused mothers’ legal consciousness transforms into a schema of entrapment: they begin to anticipate that asserting boundaries will result in institutional punishment, not protection. They are caught in a paradox where withdrawing from legal proceedings is perceived as neglect, while participation exposes them and their children to further harm. Their legal consciousness, then, is not shaped merely by notions of protection or abandonment, but by the recognition that legality often reproduces the same coercive dynamics they hoped to escape.

Taken together, these experiences mark a turning point in abused mothers’ legal consciousness: from efforts to navigate and comply with the legal system, to a deeper awareness of its entanglement in sustaining coercive dynamics. The system is no longer seen as inattentive or inefficient, but as a legitimizing force that reproduces violence and control under the language of due process, fairness, and parental equality. This realization, emerging not from isolated incidents but from patterned encounters across legal procedures, forms the groundwork for what this study conceptualizes as Entrapped Legal Consciousness. In this mode of consciousness, mothers come to see the legal system as a site that reconfigures their resistance, restricts their options, and reinscribes the power relations they sought to dismantle. The following section elaborates on this conceptual framing and its theoretical implications.

4. Theoretical Integration

The concept of Entrapped Legal Consciousness builds on longstanding and rapidly developing bodies of literature to contribute a generative theoretical lens for understanding how legal meaning is shaped in contexts of ongoing coercion. It bridges feminist legal scholarship, theories of structural and institutional violence, and socio-legal understandings of legal consciousness by showing how mothers’ experiences of legality in post-separation abuse proceedings are not merely reactive but constitutive and relational. Building on others, this study avoids the tendency to treat legal consciousness as a cognitive stance or static belief and instead considers it as a dynamic, embodied navigation shaped through continuous exposure to overlapping forms of violence—private, institutional, and state. In this way, Entrapped Legal Consciousness offers a theoretical framework for analyzing how legality can become an enduring conduit of continued abuse.

The three orientations presented through the analysis—Institutional Trust and Disillusionment, Institutional Asymmetry, and Recognizing Entrapment—represent distinct yet interrelated orientations through which abused mothers interpret, understand and respond to their encounters with the family law system after separation. While participants did not name these processes directly, their accounts consistently pointed to a growing recognition that legal mechanisms—such as repeated filings, mandatory procedures, and courtroom formalities—often enabled patterns of pressure and control to persist. These mechanisms were experienced not simply as bureaucratic or neutral, but as structurally mirroring the imbalance of power that abused mothers had already faced. Rather than forming a linear progression, these orientations coexist and interact dynamically, reflecting the complex and often contradictory ways in which legal consciousness is shaped under conditions of post-separation abuse. This dynamic resonates with

Stark’s (

2007;

2020) insights into legal coercion and coercive control, and complements

Katz’s (

2022) argument that post-separation abuse is often misunderstood or minimized by legal institutions.

While each orientation illustrates a different disposition toward the legal system, they are not mutually exclusive. Rather, they operate simultaneously and relationally, shaping a fractured yet enduring form of legal consciousness. Taken together, they reveal how legal consciousness becomes not only a lens through which mothers make sense of legal authority, but also a dynamic constellation that entangles them in ongoing vulnerability. Crucially, what binds these orientations is a shared condition of constraint: abused mothers remain embedded in a system that promises protection while often facilitating harm. This paradox is encapsulated in the concept of Entrapped Legal Consciousness—referring to how legal knowledge, beliefs, and strategies become entangled with the very institutional logics that sustain post-separation abuse. As mothers learn to “play by the rules” to protect their children or maintain credibility, they come to understand that what the system frames as fairness or balance often masks and reinforces asymmetrical power relations rooted in their experiences of coercion. Their legal consciousness becomes a survival tool while simultaneously being forged within structures that rarely offer them exit routes.

This conceptual framework builds as well on the Trias Violentae framework, which distinguishes between private, structural, and state violence. Each orientation marks an aspect in the internalization of this entrapment: a shift occurs from trust followed by disillusionment, to an understanding of the need to navigate what are experienced as asymmetric procedures. Facing the result and coping with the implications of judicial decisions in their everyday lives, ultimately, mothers understand systemic complicity as a strategic way to minimize the threats in their lives in ways that echo the abusive relationship. These empirical findings are situated within the Trias Violentae framework, which allows us to trace how violence shifts form: from private (between the abused mother and her abusive ex-partner), to structural (maintaining unequal power relations), to state (legitimizing processes and reinstating private threats heard during the abusive intimate relationship).

While these forms of violence are often analytically separated, post-separation abused mothers’ experiences reveal how they operate in tandem. Moreover, their legal consciousness does not merely reflect each layer individually but rather functions as a pathway that connects them. It is through legal consciousness that private acts of coercion are interpreted, responded to, and often re-legitimized by institutional and state agents. The interrelation between the three orientations that emerged from the narratives reveals a broader structural pattern that goes beyond individual experiences. The model presented in

Figure 1 visualizes this dynamic, illustrating how abused mothers’ legal consciousness maintains a recursive movement between the private, institutional, and state levels of violence. Each of the three orientations contributes a layer to the formation of Entrapped Legal Consciousness. The first theme, Institutional Trust and Disillusionment, captures the initial hope for protection and the gradual realization of its absence. The second, Institutional Asymmetry, reveals how legal norms and procedures are experienced as they operate unevenly in ways that mirror the power relations of abusive ex-partners. The third, Recognizing Entrapment, marks the point at which abused mothers perceive their legal compliance as cultivating continued control, showing how violence shifts and adapts through legal engagement. Entrapped Legal Consciousness thus crystallizes how legality might be formed at the intersection of these three domains.

Through this lens, Entrapped Legal Consciousness emerges as a cognitive and emotive response to the law’s legitimizing function, where legal norms, rather than breaking cycles of abuse, can inadvertently reestablish power relations that keep abused mothers bound to systems of control. Participant 34 described her shock and disbelief upon learning that her abusive ex-partner, despite his domestic violence history and a criminal conviction in a separate case, was granted full parental rights. To her understanding, the state’s regulatory apparatus effectively revalidated the violent ex-partner as a legitimate rights-holder, thereby intensifying the abused mothers’ sense of exposure. Here, legal consciousness is shaped not by legality’s impartiality but by its capacity to erase context, stripping away the relational and historical dimensions of violence and abuse. This reflects the transition from structural to state violence: a movement where legality becomes complicit in reestablishing control, even when formal protective measures are nominally in place. Similarly to her description, we find that even criminal conviction might not put the abused mothers’ need for protection before the abusive ex-partner’s legal rights, as

Avieli (

2025) exemplifies: “

perpetrators abused the rights granted to them by law, such as the rights to make phone calls or to send letters from prison and their rights as parents and bank account owners, to continue abusing their former partners” (

Avieli 2025, p. 8). In this dynamic, the family law system does not just mirror private abuse, it translates it into legal obligations, expectations of cooperation, or institutional silencing (

Porter 2020). For example, an act of parental manipulation may be repackaged as a custody issue, as Participant 28 recounted, her request to relocate near her parents was denied by the court—effectively reinforcing her ex-partner’s strategy of isolation:

He got everything he wanted. Even the most absurd things, like the fact that he wouldn’t let me move to live above my parents… Instead of growing up in a supportive environment with help, you’ll stay here… you won’t move away from me.

(P28)

The ruling has actively extended the ex-partner’s control by transforming his coercive preferences into legally enforceable obligations. Through this lens, legality reactivates the architecture of control under conditions of institutional asymmetry. Her legal consciousness adapts to this logic, recognizing that compliance with legal norms often means perpetuating the very patterns of domination she sought to escape.

Another example is how an abused mother’s attempt to protect her child may be framed as noncompliance. Participant 7’s account encapsulates the paradox faced by many abused mothers navigating post-separation legal processes. Even when the court formally acknowledges their risk and issues protective orders, the enforcement of contact and visitation obligations continues to expose them and their children to harm. The private violence she sought to escape has been reinstated and the very authority meant to shield her becomes a pathway through which coercion is maintained.

Drawing on Schinkel’s concept of the “Trias Violentae,” the model presented in

Figure 1 illustrates how violence can move between private, institutional, and state domains.

The dynamics between different levels of violence are cyclical, as

Schinkel (

2010) suggests. From this movement, a legal consciousness is formed that fosters a sense of entrapment: a subjective experience of entanglement within the legal system. Over time, abused mothers internalize what they make of as the logic behind the outcomes of legal decisions: a logic that reaffirms the authority of legality while rendering them vulnerable to further control. Entrapped Legal Consciousness, then, is not only a psychological state—it is a structural position, forged at the intersection of intimate violence, institutional processes, and state-sanctioned authority. It captures how legal norms, procedures, and narratives can coalesce to reproduce harm across domains, making it increasingly difficult for abused mothers to extract themselves from the cycle of violence.

5. Conclusions

This study set out to explore how abused mothers who experience post-separation abuse engage with, interpret, and are affected by their encounters with the family law system. Drawing on in-depth narratives and a thematic analysis using legal consciousness theory as a framework, the findings reveal how post-separation abused mothers’ legal consciousness takes shape through three distinct yet interconnected orientations that may exist simultaneously or shift in prominence as mothers navigate family law proceedings. Rather than representing linear stages, these reflect different orientations toward legality that mothers may experience concurrently, creating the contradictory relationship with legal institutions that characterizes Entrapped Legal Consciousness.

Through the analytic lens of three legal orientations—Institutional Trust and Disillusionment, Institutional Asymmetry, and Recognizing Entrapment—the study captures the concept of second-order abuse, which may appear in contradictory ways as post-separation abused mothers navigate the legal system in search of protection, justice, and stability.

The empirical contribution of this study reorganizes and reinterprets existing patterns identified in the literature on post-separation abuse by introducing a new analytical lens: three legal orientations that illuminate how abused mothers experience the legal system after separation. While our study does not claim to evaluate the family law system’s practices as a whole, these subjective accounts reveal patterned experiences that contribute to sociolegal understandings of post-separation abuse. Rather than treating known phenomena, such as institutional dismissal, procedural harm, and coercive control through custody, as isolated or cumulative, the analysis reveals how abused mothers navigate these experiences through shifting orientations. This framework enables a rich understanding of how the encounter with the family law system itself shapes abused mothers’ perceptions, strategies, and vulnerabilities, offering a nuanced empirical account of how post-separation abuse can be sustained under legal proceedings and judicial decisions.

The analytical contribution of the introduction of Institutional Trust and Disillusionment, Institutional Asymmetry, and Recognizing Entrapment as co-existing orientations expands the interpretive range of legal consciousness theory, particularly in light of

Ewick and Silbey (

2003) and others’ work on narrative tensions and simultaneous legal orientations. By extending the framing of mothers’ responses in linear terms—as belief, disappointment, or rejection—to the coexistence of conflicting orientations toward legality that are strategically managed under coercive conditions, these orientations clarify how abused mothers continue to engage with the law while simultaneously recognizing its limitations, and how this ambivalence reflects deeper structural dynamics. As such, they deepen our analytic vocabulary for understanding legal meaning-making in the context of gendered structural violence.

The conceptual contribution of the concept of Entrapped Legal Consciousness synthesizes the three orientations in ways that bridge individual experiences and structural analysis. Specifically, it allows us to articulate how legal consciousness can serve not only as a reflection of institutional experiences, but also as a mediating force that facilitates the movement of violence across private, structural, and state domains. By unpacking the three orientations and introducing the concept of Entrapped Legal Consciousness, the study illuminates important mechanisms that create a pathway by which legality may inadvertently perpetuate vulnerability and hinder recovery. Building on prior frameworks, such as legal consciousness theory, this study extends existing understandings by illustrating how these domains become intertwined through legal perceptions and expectations. While earlier approaches have shed light on critical dimensions of abused mothers’ experiences, the combined lens of the three orientations offers a distinct perspective on the recursive entanglement of agency, coercion, and legality. Within the Trias Violentae framework, this integrated view helps explain how abused mothers become entrapped in a system that simultaneously demands their participation and reproduces their vulnerability. This conceptual framework aims to enrich ongoing debates by showing, on a granular level, how legal consciousness may contribute to the endurance of coercive dynamics under conditions of formal legitimacy.

The empirical analysis of post-separation abused mothers’ narratives offers a grounded entry point into their dynamic and relational legal consciousness. Analyzing their experience, we trace how abused mothers come to perceive the legal system as ineffective and structurally complicit. To situate these dynamics in a broader explanatory framework, we draw on the Trias Violentae model, which theorizes how violence maintains its power between private, structural, and state domains. This may help in understanding abused mothers’ legal decision-making (

Spearman et al. 2024a, p. 189).

Implications for Legal Practice and Policy

The findings of this study highlight the need for legal systems, particularly the family law system, to consider recognizing post-separation abuse not merely as a private or interpersonal issue, but as a structurally mediated form of coercion. When courts default to a formalist, symmetrical interpretation of legal conflict—treating both parties as equally positioned—they risk obscuring histories of control and perpetuating violence and abusive behaviors. Incorporating assessments that differentiate between types of partner violence may support more appropriate legal responses and shift judicial attention from procedural symmetry to substantive protection.

Participants’ accounts underscore the importance of developing an attentive relationship with law, context-sensitive legal procedures that do not reproduce power imbalances under the guise of fairness. Small procedural adjustments—such as limiting unnecessary contact with abusive ex-partners, recognizing patterns of legal harassment, and tailoring custody and contact orders with specificity—may significantly affect the abused mothers’ capacity to safely navigate the legal proceedings. More broadly, this research seeks to call for institutional investment in training judges to recognize long-term patterns of post-separation abuse and control, in order to treat abused mothers’ narratives as complex legal knowledge. Ultimately, interrupting the cycle of legitimized legal coercion demands a revision of tools and policies (

Easteal and Grey 2013;

Easteal et al. 2019;

Spearman et al. 2024b, pp. 14–15;

Pears and Easteal 2025), but also a reorientation of legal consciousness within the institutions themselves.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, all authors; methodology, all authors; validation, all authors; formal analysis, all authors; investigation, all authors designing the investigation; resources, all authors; data curation, primarily E.P.; writing—original draft preparation, all authors; writing—multiple reviews, rewriting and editing, all authors; visualization, E.P.; supervision, A.R.B. and G.R.E.; project administration, all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Faculty of Law of Haifa University, approval number 015/24, on 9 of January 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Law in the University of Haifa, approval number 051/24, on 9 of January 2024.

Data Availability Statement

Interview data is publicly unavailable due to privacy and ethical restrictions. Requests to view can be forwarded to the authors and will be considered pursuant to the IRB approval obtained to conduct the research.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used generative AI tools (specifically the premium version of Grammarly, Chat-GPT-4 and Claude Opus 4) for language editing purposes, including grammar correction, sentence structure improvement, spelling, punctuation, and formatting. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Descriptive table of Interviewees’ Demographic Background.

Table A1.

Descriptive table of Interviewees’ Demographic Background.

| Variable | Descriptive Group | N (%) |

|---|

| Years since divorce | 2–4 | 13 (40.6%) |

| 5–7 | 11 (34.4%) |

| 8–10 | 5 (15.6%) |

| <10 | 3 (9.4%) |

| Legal family court domains | civil | 23 (71.9%) |

| religious | 5 (15.6%) |

| appellate | 4 (12.5%) |

| Number of joint minors | 1 | 14 (43.8%) |

| 2 | 10 (31.2%) |

| 3–4 | 6 (18.8%) |

| 5–6 | 2 (6.2%) |

| Geography | Rural | 5 (15.6%) |

| Major cities | 18 (56.3%) |

| Urban suburbs | 9 (28.1%) |

Self-identified

Culture/Religion | Jewish | 30 (93.8%) |

| Muslim | 1 (3.1%) |

| Druze | 1 (3.1%) |

References

- Abrego, Leisy J. 2008. Legitimacy, Social Identity, and the Mobilization of Law: The Effects of Assembly Bill 540 on Undocumented Students in California. Law & Social Inquiry 33: 709–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrego, Leisy J. 2018. Renewed Optimism and Spatial Mobility: Legal Consciousness of Latino Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals Recipients and Their Families in Los Angeles. Ethnicities 18: 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Shayne R., Stephen A. Anderson, Kristi L. Palmer, Matthew S. Mutchler, and Louisa K. Baker. 2010. Defining High Conflict. The American Journal of Family Therapy 39: 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avieli, Hila. 2024. Parenting-Related Abuse among Women Survivors of Attempted Intimate Partner Homicide. Child Abuse & Neglect 158: 107119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avieli, Hila. 2025. Ongoing Abuse Following Survival of Attempted Intimate Partner Homicide. Journal of Family Violence 21: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, Nicholas, Ella Benedetti, and Sydney Franzmann. 2024. Exploring Litigation Abuse in Ontario: An Analysis of Costs Decisions. Family Court Review 62: 936–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, Adrienne. 2024. Chapter 14: Domestic Abuse, Parental Alienation and Family Court Proceedings. In Research Handbook on Domestic Violence and Abuse. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. Available online: https://www.elgaronline.com/edcollchap/book/9781035300648/book-part-9781035300648-21.xml (accessed on 29 August 2025).