Tax Control Between Legality and Motivation: A Case Study on Romanian Legislation

Abstract

1. Introduction: Legal Framework of Tax Control in Romania

1.1. Concept of Tax Control and Its Relevancy

1.2. Forms of Tax Control Under Romanian Legislation

1.2.1. Fiscal Inspection

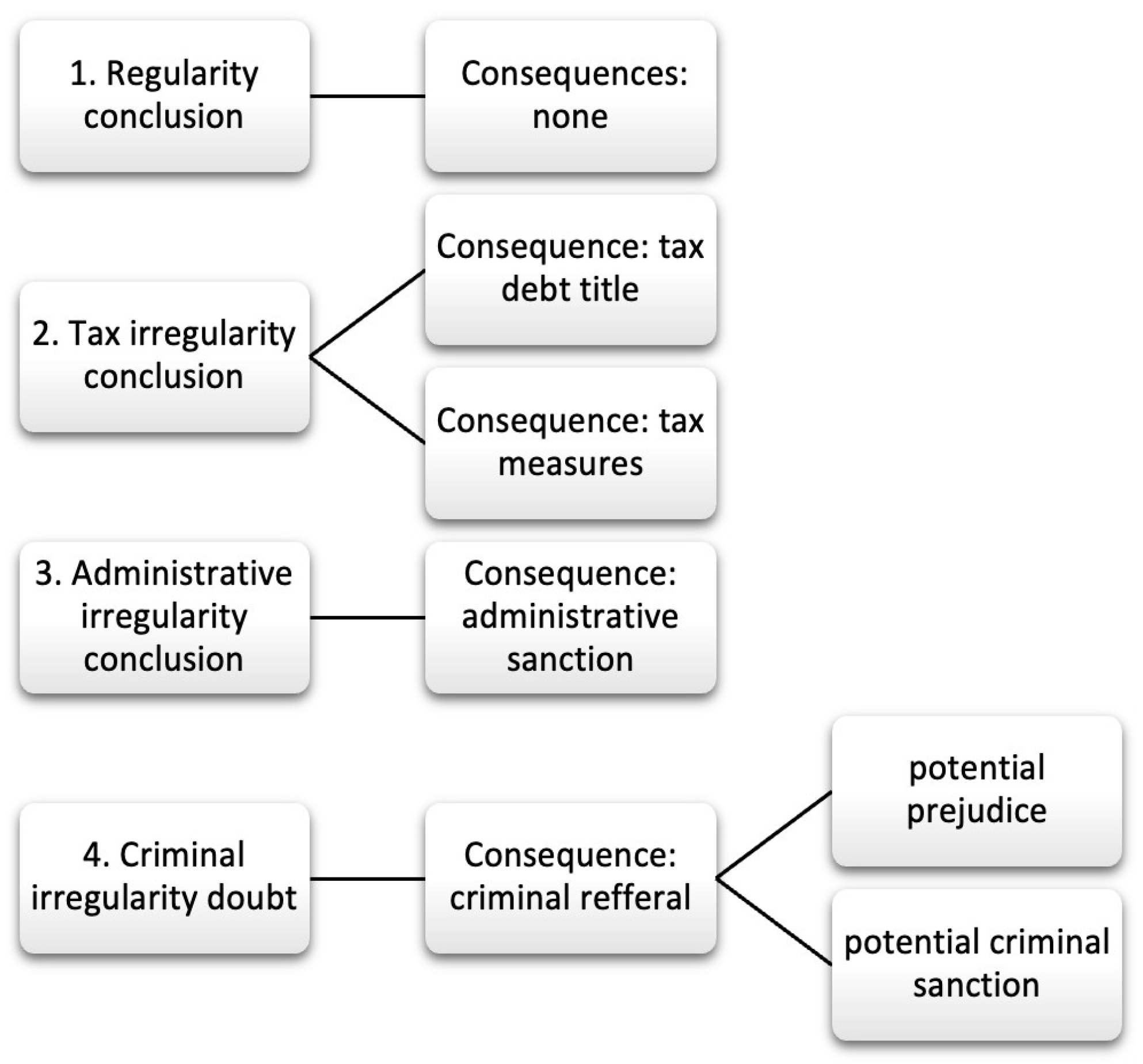

- If the fiscal inspection body identifies a completely legal state of facts, as the tax bases and debts were correctly established by the taxpayer, a decision not to change the taxable base is issued;

- If the fiscal inspection reveals an illegal tax situation, but which does not affect the tax result nor generate additional tax claims, a decision to impose non-patrimonial measures is issued;

- If an illegal tax situation that requires the establishment of additional tax debts is found, a tax decision is issued.

1.2.2. Unforeseen Control

1.2.3. Antifraud Control

1.2.4. Personal Patrimony Audit

1.2.5. Documentary Audit

2. Methods

2.1. Methodology

2.2. Variables Review

2.3. Hypotheses

- Are tax control forms legal institutions with precise purpose and well-determined shapes and effects?

- Are tax control forms a substantial contributor to aggregating fiscal revenues as part of tax effectiveness?

- Are tax control forms a substantial source of identifying and sanctioning illegal fiscal behavior as an agent of tax compliance?

- The current legal frame of tax control is heterogenous, incomplete, and conditioned by administrative practices (Blanc 2012);

- Debt collection is an inconstant effect of tax control forms with a marginal overall input in budget dynamics;

- Identifying illegal fiscal behavior relies on tax control, but administrative sanctions and criminal sanctions have different rates and unpredictable moments of occurrence.

3. Findings and Discussions

3.1. A Map of Tax Control Forms by Legal Content

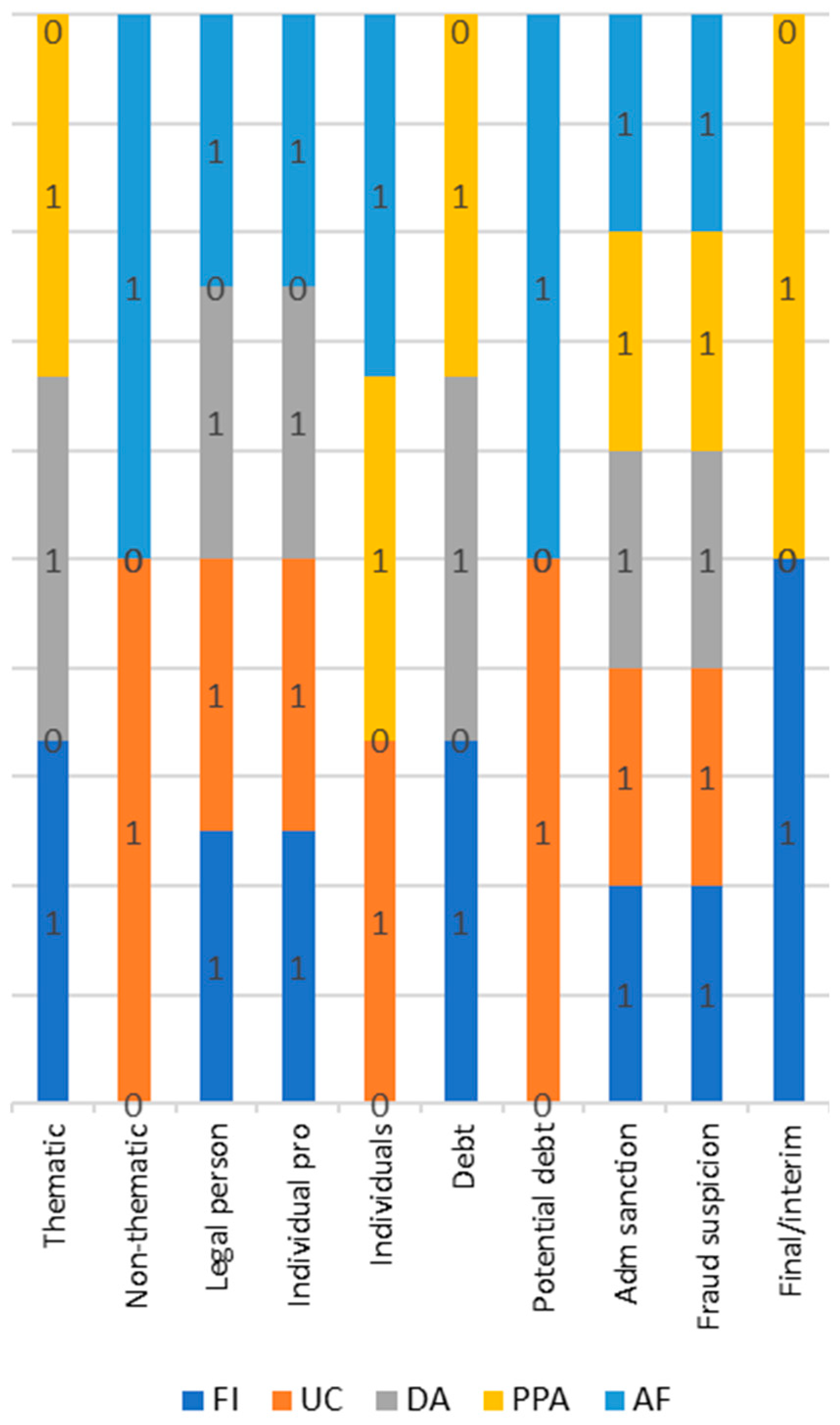

3.1.1. A Diversity Matrix

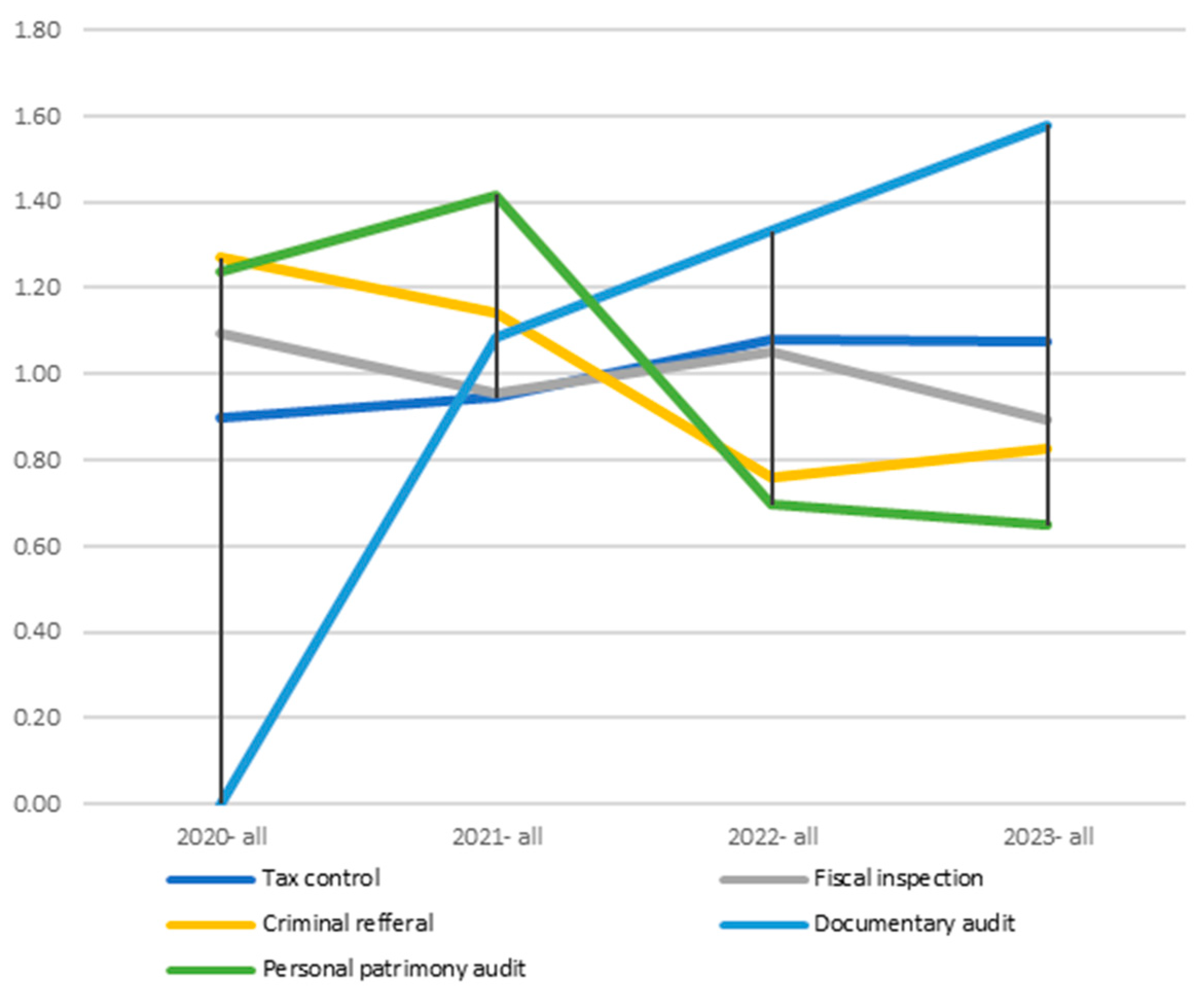

3.1.2. The Internal Equilibrium

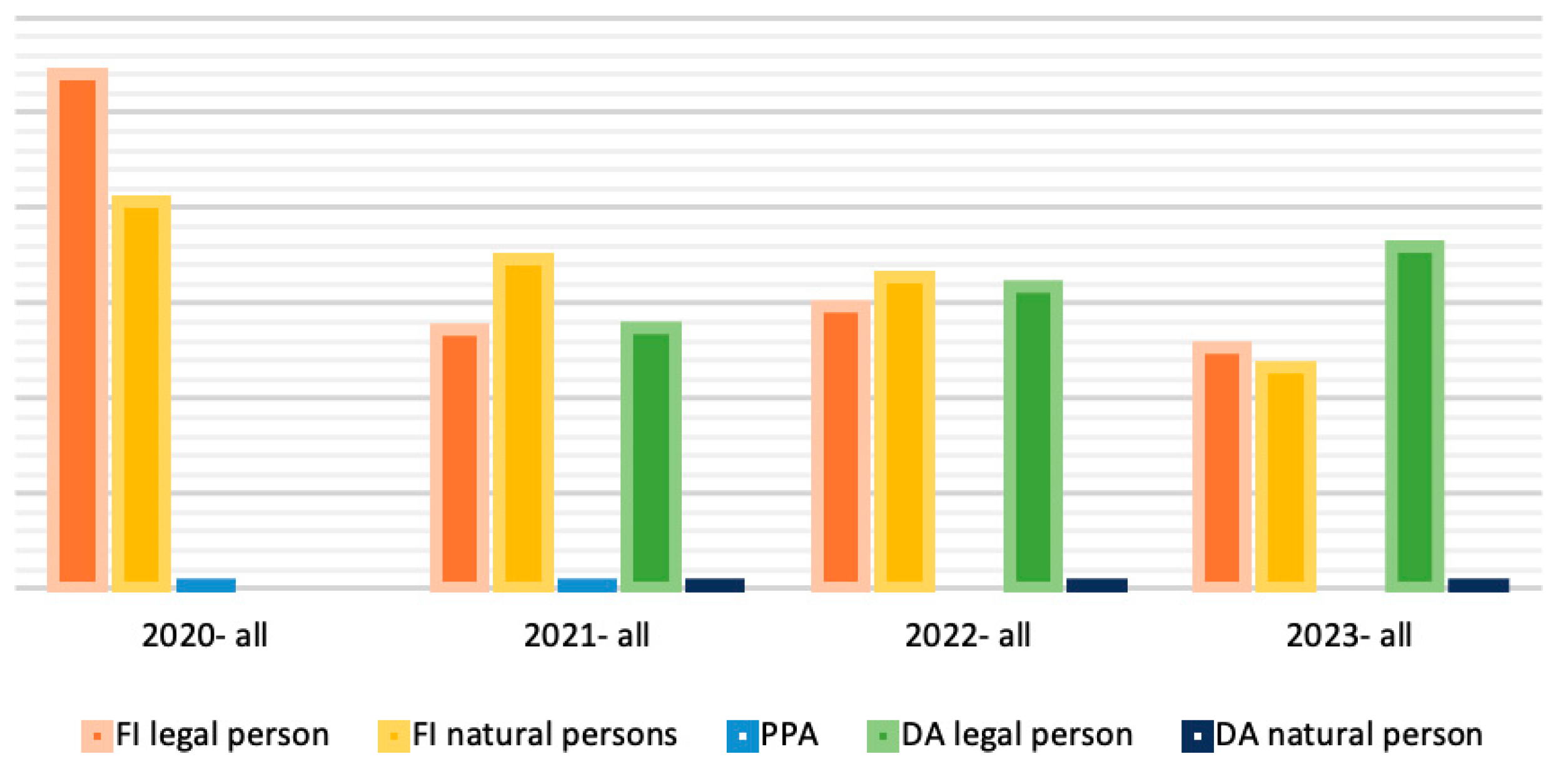

3.1.3. A Shared Task in an Autophagic System

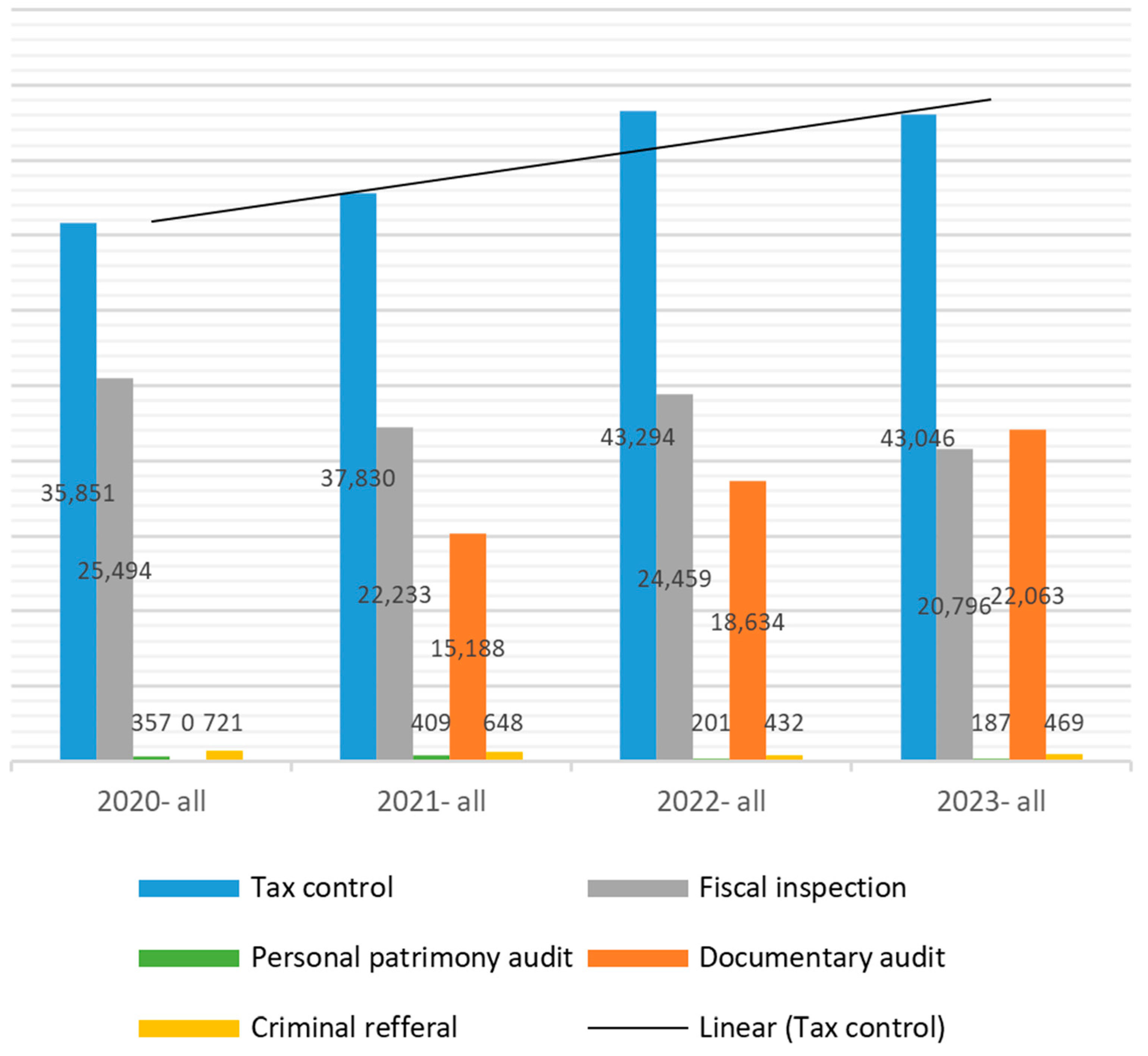

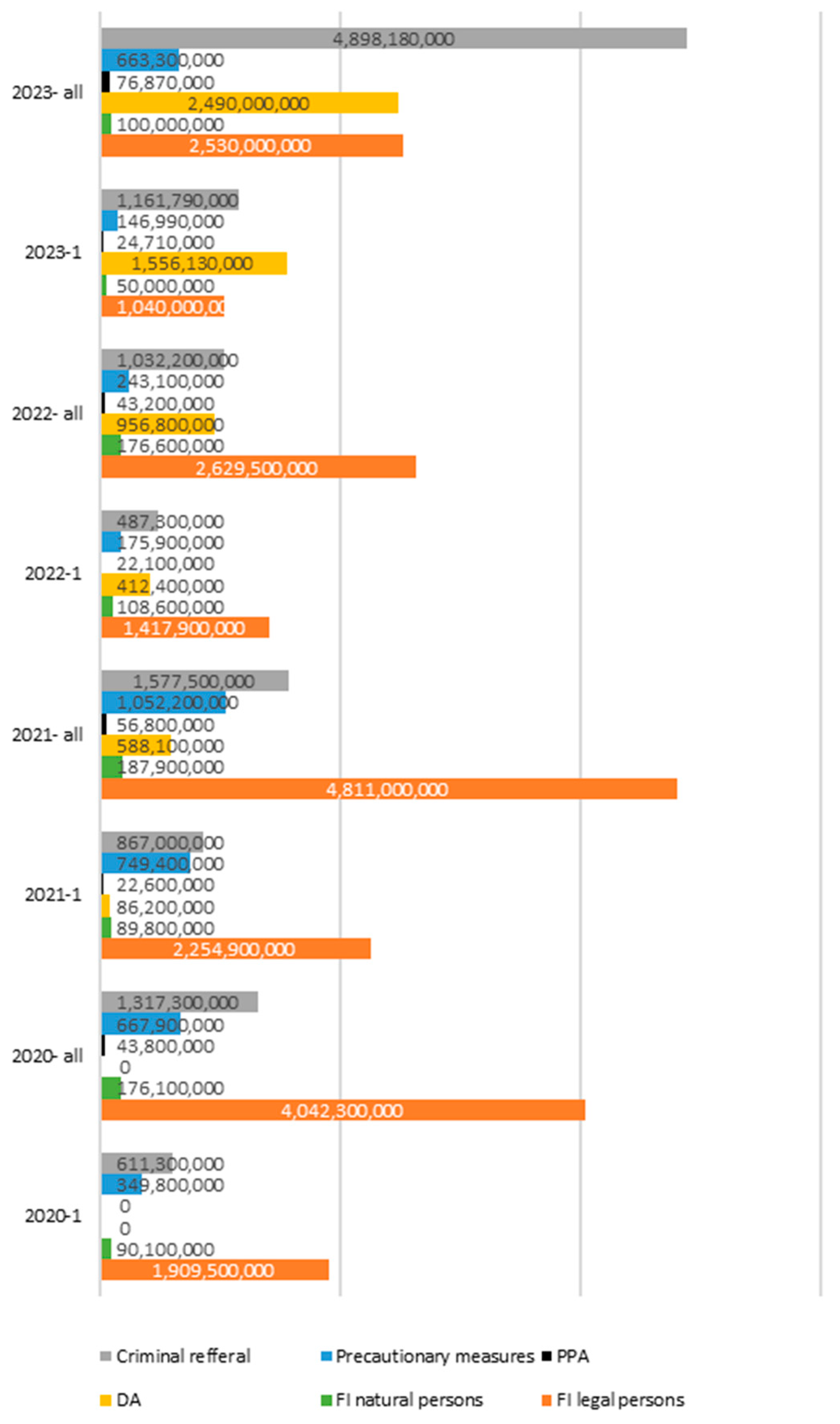

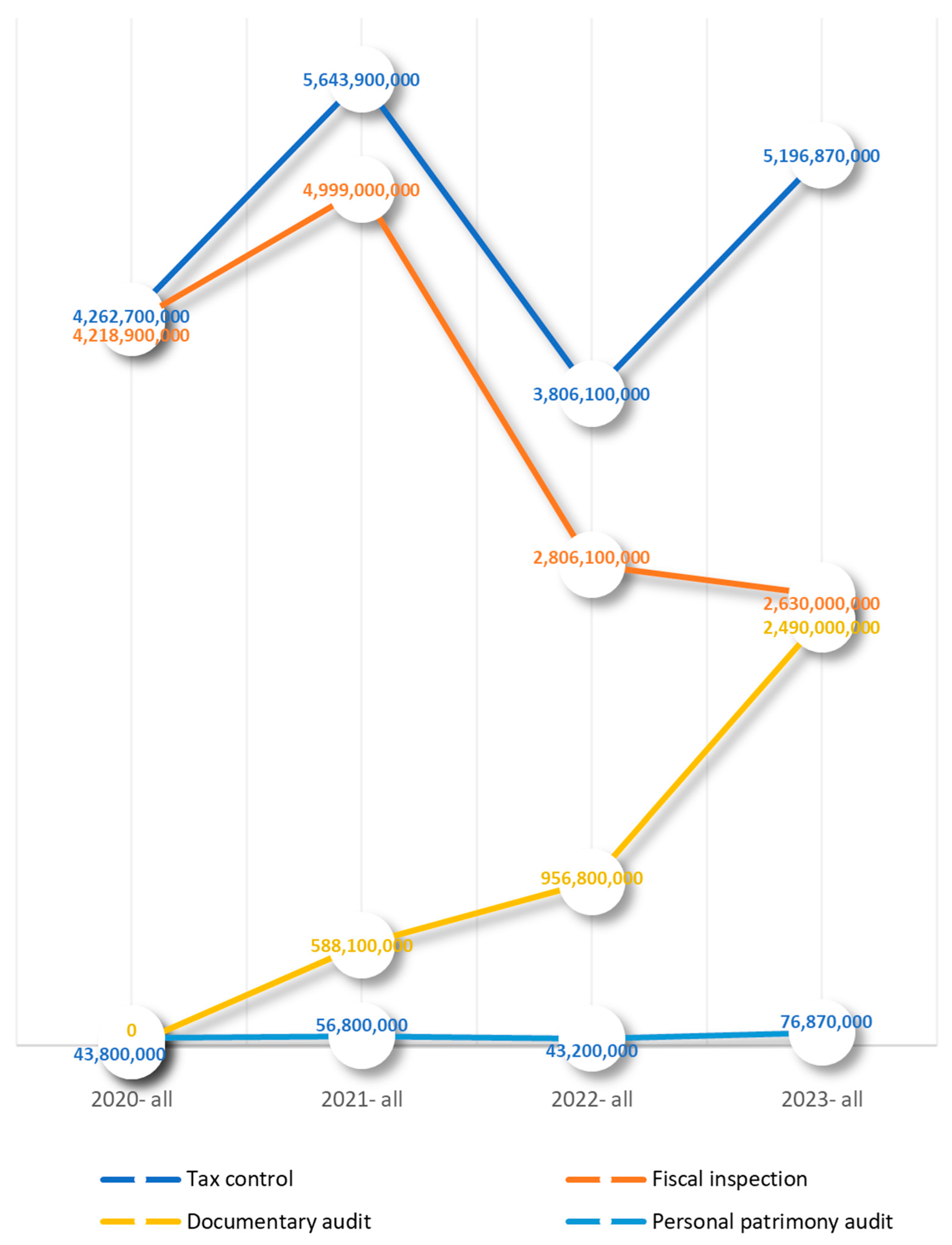

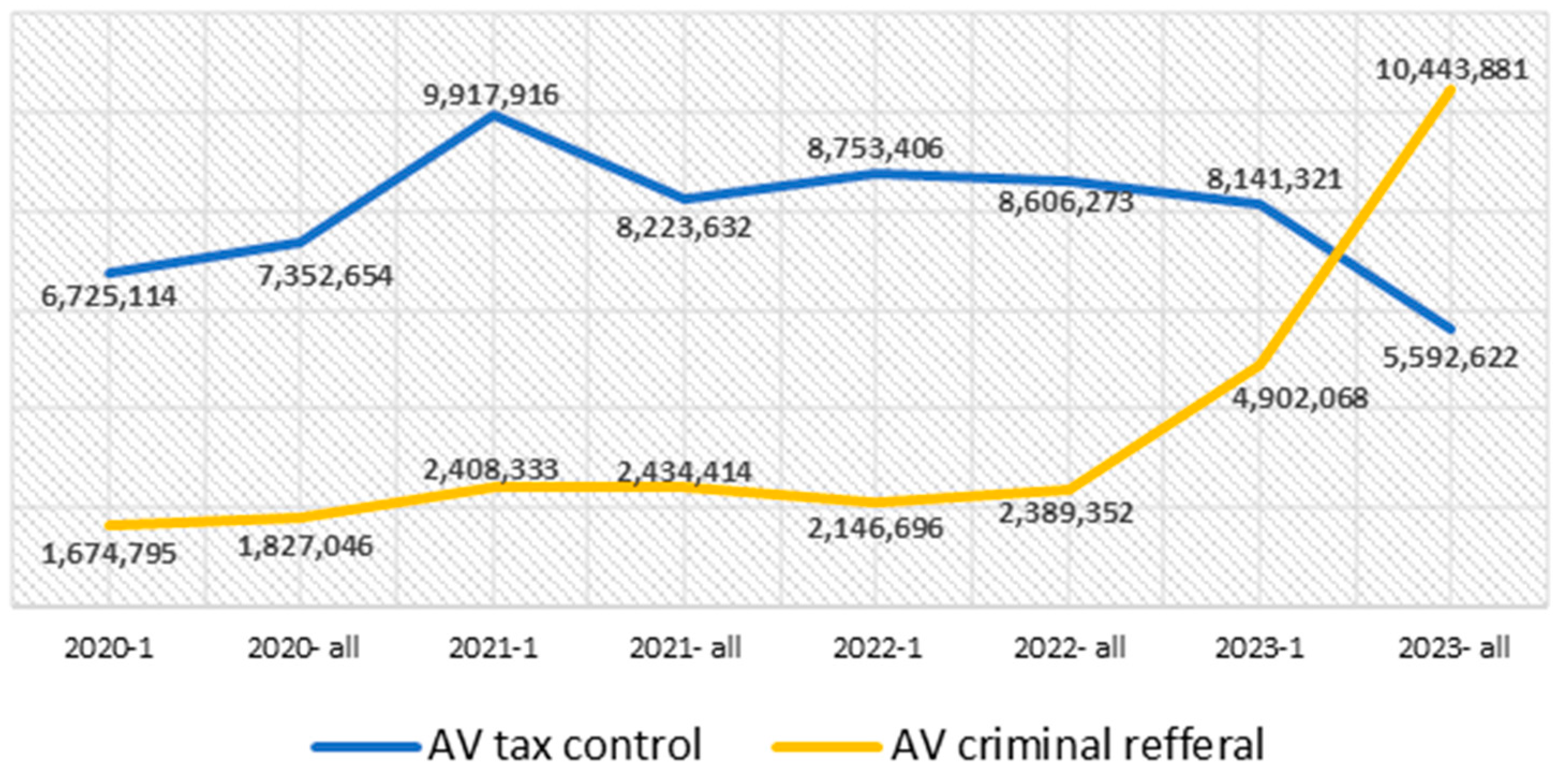

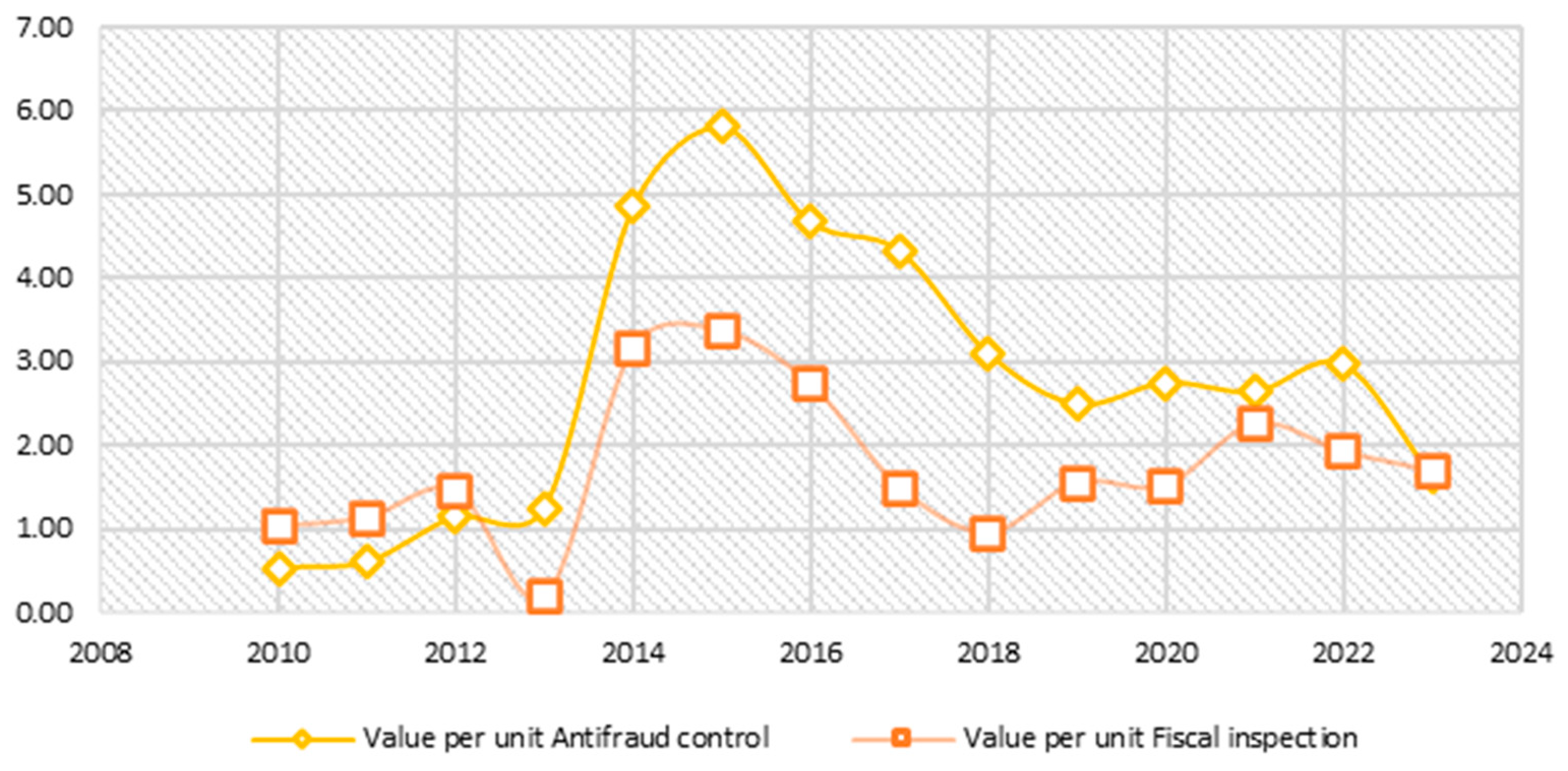

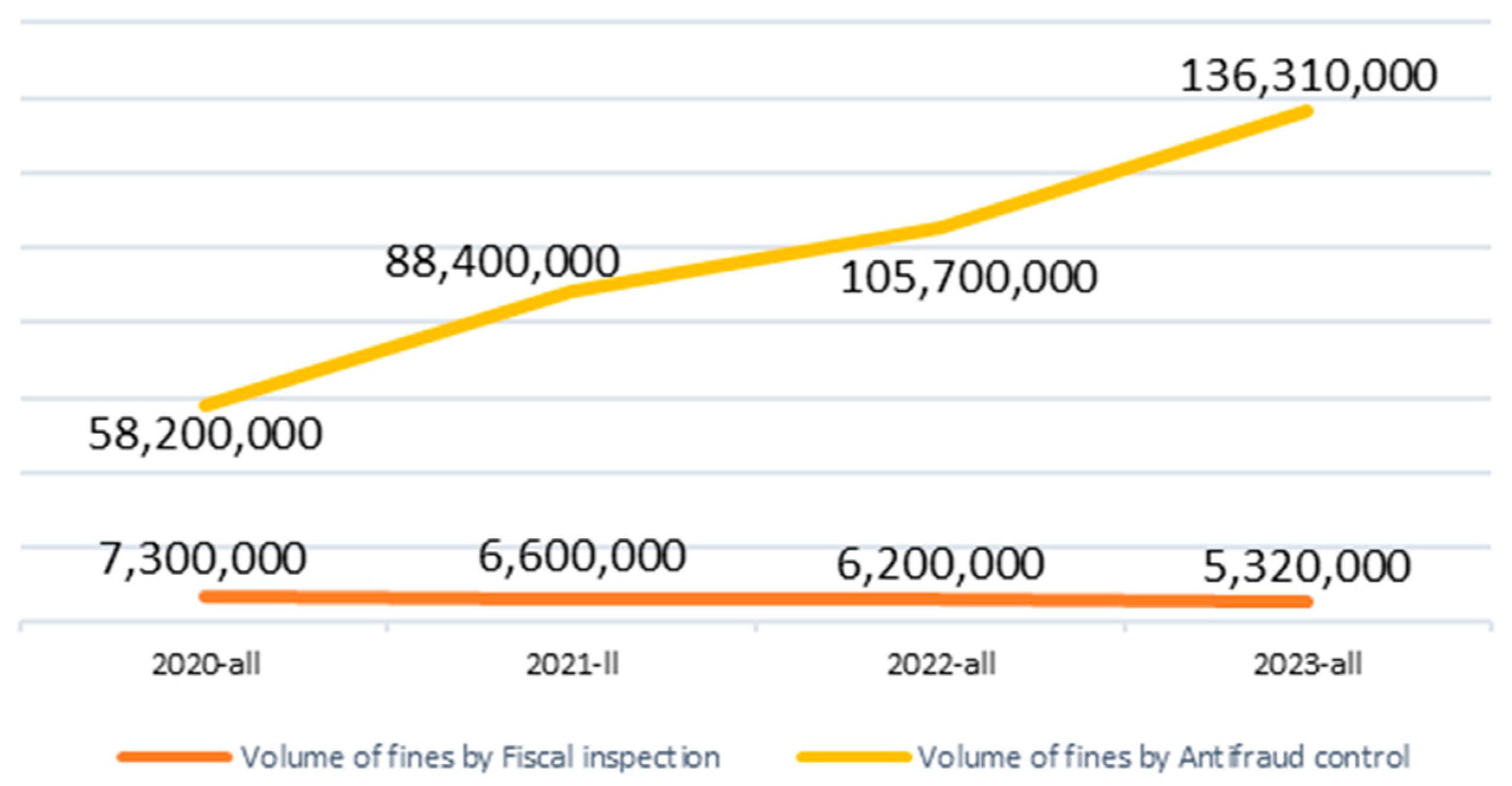

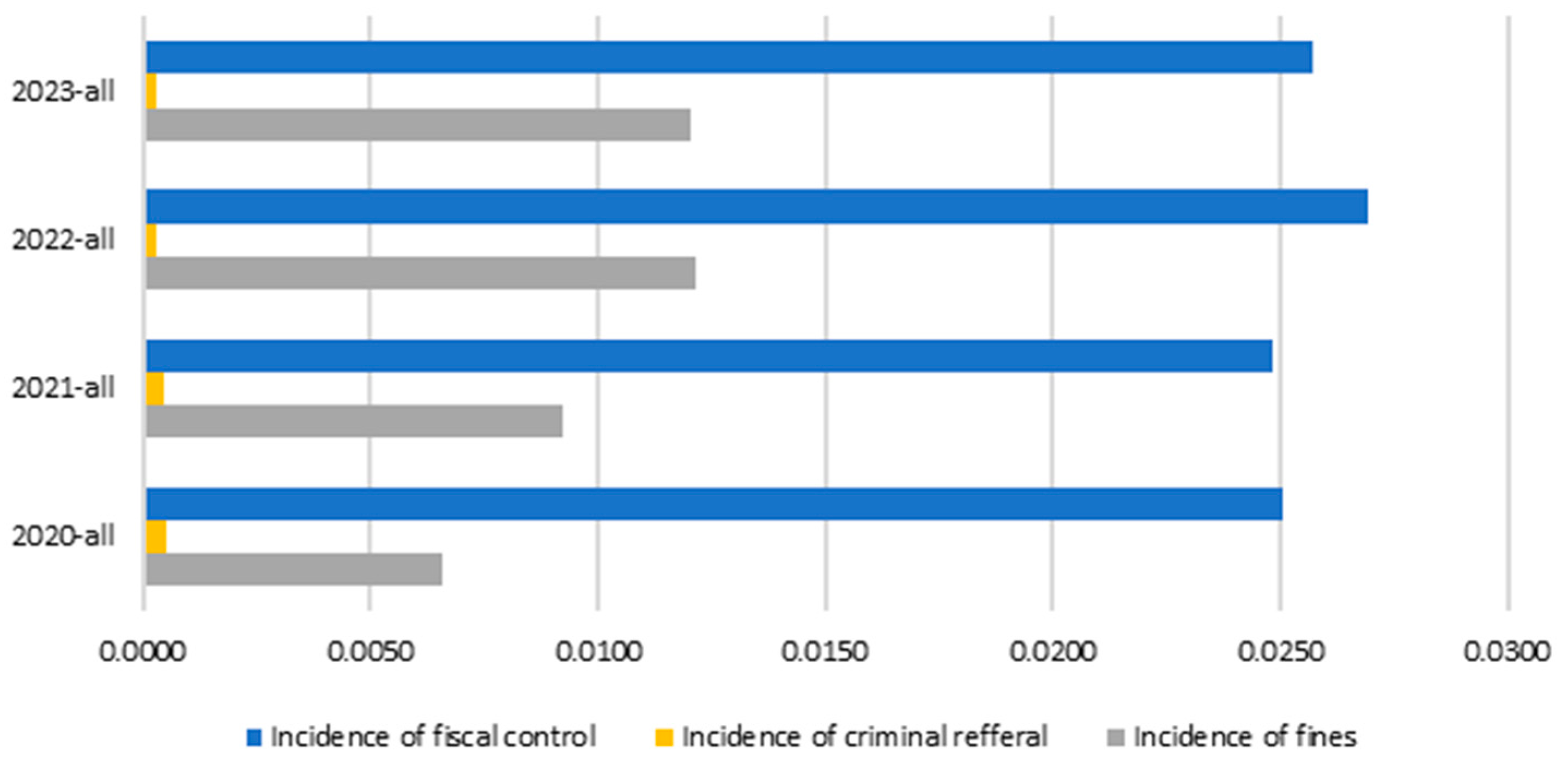

3.2. Debt and/or Potential Debt

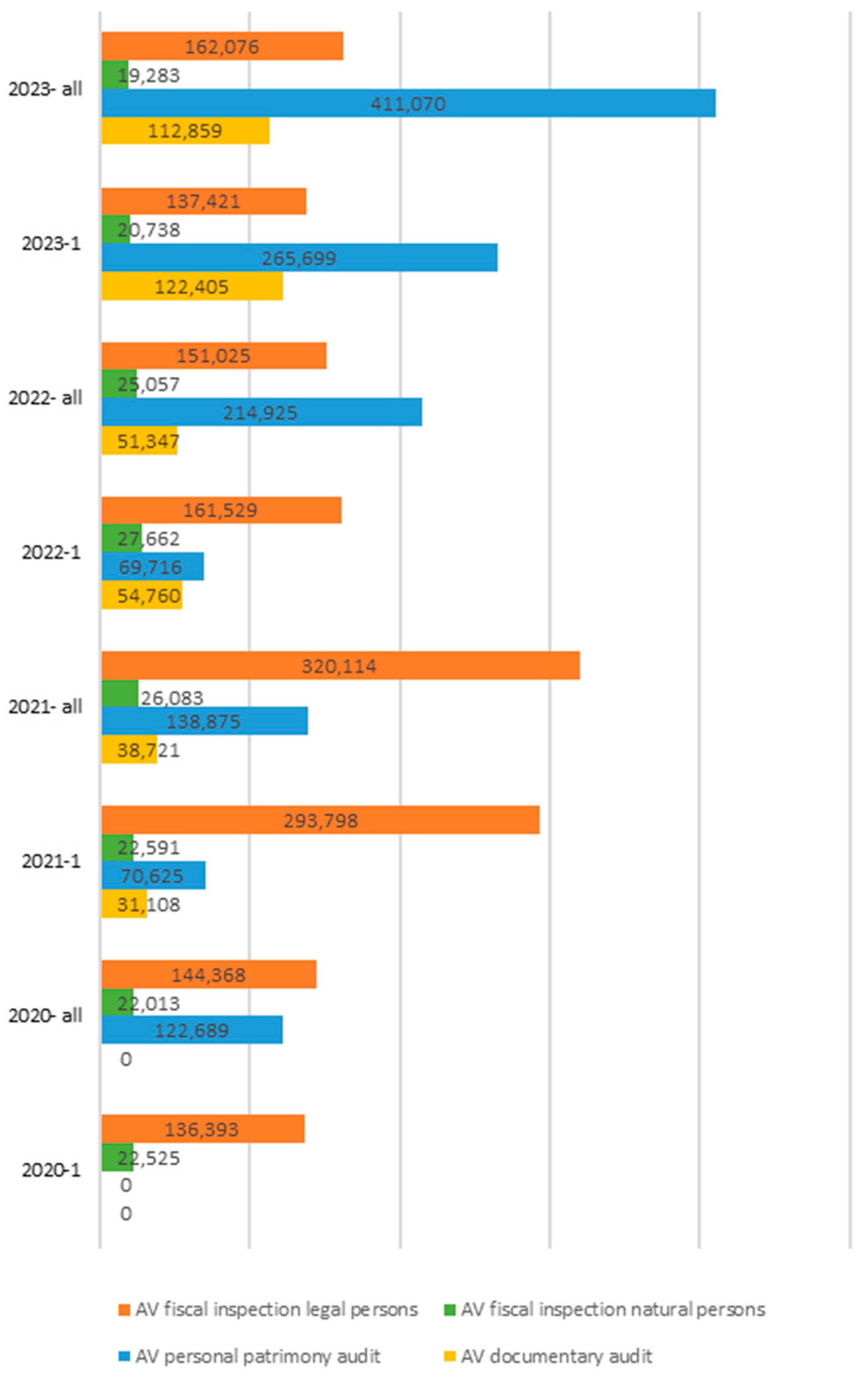

3.3. Tax Control as Tool for Fighting Fiscal Non-Complaince and Fiscal Fraud

4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

Primary sources

Law no. 207/2015 regarding the Romanian Fiscal Procedure Code, M.Of. no. 547 of July 23, 2015.Emergency Govern Ordinance no. 74/2013 regarding some measures to improve and reorganize the activity of the National Agency for Fiscal Administration, as well as to amend and supplement some normative acts, M.Of. no. 389 of June 29, 2013.Order of the Minister of Public Finance no. 675/2018 regarding the approval of the indirect methods of establishing incomes and the procedure for their application, M.Of. no. 257 of March 25, 2018.National Agency for Fiscal Administration, Reports and studies for 2020–2023. Available online: https://www.anaf.ro/anaf/internet/ANAF/despre_anaf/strategii_anaf/rapoarte_studii (accessed on 20 November 2024).Government Ordinance no. 8/2013 for the amendment and completion of Law no. 571/2003 regarding the Fiscal Code and the regulation of some financial-fiscal measures, M.Of. 54 of 2013.01.23.Government Ordinance no. 29/2011 for the amendment and completion of Government Ordinance no. 92/2003 regarding the Fiscal Procedure Code, M.Of. 626 of 2011.09.02.European Commission, VAT gap in the EU—Country Report Romania, Brussels, 2023. Available online: https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/document/download/6a38fb0c-4a3d-4326-a249-8bebcb5b60af_en?filename=ROMANIA%20Country%20specific%20VAT%20gap%20report%202023.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2024).Superior Council of the Judiciary, Decision no. 57 of April 6, 2023. Available online: http://old.csm1909.ro/csm/linkuri/10_05_2023__110863_ro.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2024).Secondary sources

- Allingham, Michael G., and Agnar Sandmo. 1972. Income tax evasion: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Public Economics 1: 323–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, James, Brian Erard, and Jonathan Feinstein. 1998. Tax compliance. Journal of Economic Literature 36: 818–60. [Google Scholar]

- Belnap, Andrew, Jeffrey L. Hoopes, Edward L. Maydew, and Alex Turk. 2024. Real effects of tax audits. Review of Accounting Studies 29: 665–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergolo, Marcelo, Rodrigo Ceni, Guillermo Cruces, Matias Giaccobasso, and Ricardo Perez-Truglia. 2018. Misperceptions about tax audits. In AEA Papers and Proceedings. Nashville: American Economic Association, vol. 108, pp. 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Blanc, Florentin. 2012. Inspection Reforms: Why, How, and with What Results. Paris: OECD, p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Blaufus, Kay, Jens Robert Schondube, and Stefan Wielenberg. 2024. Information sharing between tax and statutory auditors: Implications for tax audit efficiency. European Accounting Review 33: 545–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostan, Ionel, and Elena Doina Dascălu. 2016. Strengthening the sustainability of public finances by means of financial law focused on the control and audit exercise. Ecoforum Journal 5: 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Codrea, Codrin. 2023. Logică Juridică. Bucharest: Curs Universitar, Hamangiu Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Costea, Ioana Maria. 2011. Inspecția Fiscala˘. Bucharest: C.H. Beck Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Costea, Ioana Maria. 2017a. Conceptul de control fiscal. Review of Juridical Sciences/Revista de Științe Juridice 31: 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Costea, Ioana Maria. 2017b. Controlul Fiscal. Bucharest: Hamangiu Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Anno, Roberto. 2009. Tax evasion, tax morale and policy maker’s effectiveness. The Journal of Socio-Economics 38: 988–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Wenyi. 2011. Several measures to perfect tax administration by law. In Education and Management. Paper Presented at the International Symposium, ISAEBD 2011, Dalian, China, August 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Elgood, Tony, Tony Fulton, and Mark Schutzman. 2008. Tax Function Effectiveness: The Vision for Tomorrow’s Tax Function. Chicago: CCH. [Google Scholar]

- Ene, Alin. 2024. Despre durata Proceselor în Instanțele din România și Sofismul Generalizării Pripite. Available online: https://www.juridice.ro/738485/despre-durata-proceselor-in-instantele-din-romania-si-sofismul-Generalizarii-pripite.html (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Fuest, Clemens, and Nadine Riedel. 2009. Tax Evasion, Tax Avoidance and Tax Expenditures in Developing Countries: A Review of the Literature. Report prepared for the UK Department for International Development (DFID). Oxford: Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation, p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Hebous, Shafik, Zhiyang Jia, Knut Løyland, Thor O. Thoresen, and Arnstein Øvrum. 2023. Do audits improve future tax compliance in the absence of penalties? Evidence from random audits in Norway. Journal of Economic Behavior Organization 207: 305–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacaljak, Matej. 2020. Paying taxes in the digital age. Bratislava Law Review 4: 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, Matthias, and James Alm. 2022. Audits, audit effectiveness, and post-audit tax compliance. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 195: 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, Matthias, and Matthew D. Rablen. 2023. Tax compliance after an audit: Higher or lower? Journal of Economic Behavior Organization 207: 157–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisi, Gaetano. 2015. Tax morale, tax compliance and the optimal tax policy. Economic Analysis and Policy 45: 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisi, Gaetano. 2023. Tax Audits, Tax Rewards and Labour Market Outcomes. Economies 11: 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marandu, Edward E., Christian J. Mbekomize, and Alexander N. Ifezue. 2015. Determinants of tax compliance: A review of factors and conceptualizations. International Journal of Economics and Finance 7: 207–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzolini, Gabriele, Laura Pagani, and Alessandro Santoro. 2022. The deterrence effect of real-world operational tax audits on self-employed taxpayers: Evidence from Italy. International Tax and Public Finance 29: 1014–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, Robert W. 2023. Why Do People Evade Taxes? Summaries of 90 Surveys. Working Paper. Fayetteville: Fayetteville State University, Department of Accounting. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza, Juan P., Jacco L. Wielhouwer, and Erich Kirchler. 2017. The backfiring effect of auditing on tax compliance. Journal of Economic Psychology 62: 284–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguera, Jose A., Francisco J. Miguel Quesada, Eduardo Tapia, and Toni Llacer. 2014. Tax compliance, rational choice, and social influence: An agent-based model. Revue française de sociologie 55: 765–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olendiy, Ostap, Karina Nazarova, Maria Nezhyva, Viktoria Mysyuk, Vitaliia Mishchenko, and Roman Rusyn-Hrynyk. 2023. Tax audit to ensure business prosperity: Trends and perspectives. Financial and Credit Activity Problems of Theory and Practice 4: 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podik, Ihor Ivanovych, Iryna Yuriyivna Shtuler, and Natalia Anatoliyivna Gerasymchuk. 2019. The comparative analysis of tax audit files. Financial and Credit Activity Problems of Theory and Practice 3: 147–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, A. Mitchell, and Steven Shavell. 1979. The optimal tradeoff between the probability and magnitude of fines. The American Economic Review 69: 880–91. [Google Scholar]

- Slemrod, Joel. 1990. Optimal taxation and optimal tax systems. Journal of Economic Perspectives 4: 157–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slemrod, Joel. 2019. Tax compliance and enforcement. Journal of Economic Literature 57: 904–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Fangfang, and Andrew Yim. 2014. Can strategic uncertainty help deter tax evasion? An experiment on auditing rules. Journal of Economic Psychology 40: 161–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasova, Victoria I., Yuri V. Mezdrykov, Svetlana B. Efimova, Elena S. Fedotova, Dmitry A. Dudenkov, and Regina V. Skachkova. 2018. Methodological provision for the assessment of audit risk during the audit of tax reporting. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 6: 371–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasquez, Carlos Alberto Velezmoro, and Flor Alicia Calvanapon Alva. 2020. La auditor’ıa tributaria preventiva y su efecto en el riesgo tributario en la empresa Protex SAC Trujillo ano 2018. 3c Empresa: Investigacion y Pensamiento Crıtico 9: 107–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vossler, Christian A., Michael McKee, and David M. Bruner. 2021. Behavioral effects of tax withholding on tax compliance: Implications for information initiatives. Journal of Economic Behavior Organization 183: 301–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yayman, Derya. 2023. Tax Audit Efficacy in Turkiye. Sosyoekonomi 31: 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoitsas, Aggelos, Dimitrios Valsamidis, Theofilitsa Toptsi, and Konstantina Tsoktouridou. 2020. Indirect Auditing Methods for Individuals Subject to Income Tax. KnE Social Sciences, 385–400. [Google Scholar]

| Thematic -1- | Non-Thematic -2- | Legal Person -3- | Individual Professional -4- | Individual Personal -5- | Fiscal Debt -6- | Potential Fiscal Debt -7- | Administrative Sanction -8- | Fraud Suspicion -9- | Consequence -10- | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiscal inspection (FI) | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Unforeseen control (UC) | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - |

| Personal patrimony audit (PPA) | ✓ | - | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Antifraud control (AC) | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - |

| Documentary audit (DA) | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 2020 All | 2021 All | 2022 All | 2023 All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenues general budget | 322,520 | 379,610 | 460,090 | 386,880 |

| Fiscal revenues | 263,600 | 311,100 | 372,600 | 240,740 |

| Tax control revenues | 4262.7 | 5643.9 | 3806.1 | 5196.9 |

| Percentage of total revenue | 1.62% | 1.81% | 1.02% | 2.16% |

| Research Hypothesis | Legal Intervention | Scope |

|---|---|---|

| (1) The current legal frame of tax control is heterogenous, incomplete, and conditioned by administrative practices | - Limiting the number of forms of control to three: one for professionals; one for individuals; and an operative one for identifying non-compliance; - Regulating a common corpus of rules for tax control: notification at least during the process; right of the taxpayer to be heard and assisted by a legal councilor; and right of access to the control file and collected evidence. | - To simplify the regulatory framework to improve predictability; - To protect the taxpayer, as the weaker party in the procedure; - To ensure transparency of the procedures and a basis for the right to a fair trial. |

| (2) Debt collection is an inconsistent effect of tax control forms, with a marginal overall input in budgetary dynamics | - Granting the effect of establishing fiscal debt to all three forms of control, doubled by the possibility to appeal the tax authorities’ solutions in court. | - To maximize the collection of budgetary revenues; - To ensure immediate reactions to a non-compliant act. |

| (3) Identifying illegal fiscal behavior relies on tax control, but administrative sanctions and criminal sanctions have different rates and unpredictable moments of occurrence. | - Regulating an order of priority for tax procedures even against criminal procedures in evaluating compliance and establishing fiscal debt. | - To respect the tax exceptionalism doctrine and have fiscal debts evaluated only by fiscal authorities. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Costea, I.M.; Ilucă, D.-M.; Galan, M.-E. Tax Control Between Legality and Motivation: A Case Study on Romanian Legislation. Laws 2025, 14, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14030034

Costea IM, Ilucă D-M, Galan M-E. Tax Control Between Legality and Motivation: A Case Study on Romanian Legislation. Laws. 2025; 14(3):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14030034

Chicago/Turabian StyleCostea, Ioana Maria, Despina-Martha Ilucă, and Maria-Eliza Galan. 2025. "Tax Control Between Legality and Motivation: A Case Study on Romanian Legislation" Laws 14, no. 3: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14030034

APA StyleCostea, I. M., Ilucă, D.-M., & Galan, M.-E. (2025). Tax Control Between Legality and Motivation: A Case Study on Romanian Legislation. Laws, 14(3), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14030034