AI Moderation and Legal Frameworks in Child-Centric Social Media: A Case Study of Roblox

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Context and Relevance of the Study

1.2. Research Questions and Objectives

- To what extent is artificial intelligence-based content moderation effective in protecting child users on platforms like Roblox?

- How do legal and ethical frameworks address the use of algorithmic systems to moderate harmful content and protect children in virtual environments such as Roblox?

- How does Roblox currently address virtual harm to children on its platform, and what regulations underpin this?

- How should virtual harm to children be conceptualized in law, and what regulatory mechanisms are needed to ensure that immersive platforms like Roblox are held accountable for failing to protect young users?

- Are avatars legal persons, and should liability be assigned in digital abuse cases in a specific way under UK law?

- Employs the theory of algorithmic governance developed by Kitchin (2017) and Hildebrandt (2018, 2020), emphasizing the consequences of decisional systems and automation for accountability, bias, and due process in regulating the digital world. When these theories consider AI systems to be more than just technical tools, they are instead regulatory agents that impact the formation of legal subjectivity, procedural justice, and ethical responsibilities within online platforms like Roblox.

- Reflects on legal frameworks for virtual worlds and considers whether existing regulations—such as the GDPR and DSA—offer adequate protection against digital harm. The evaluation is grounded in the context of child protection in the UK, drawing on national interpretations and enforcement practices to assess how effectively these frameworks address risks on platforms like Roblox.

- Reflects on avatars’ legal personhood and whether they should have independent legal identities and liability arrangements in instances of digital wrongdoing.

1.3. Methodological Approach

- Legal Analysis—The study conducts doctrinal legal analysis regarding major regulatory tools like the GDPR, the Digital Services Act (DSA), and the UK Online Safety Act. It makes systematic interpretations of provisions in statutes by applying traditional legal interpretational techniques like textual, purposive, and contextual interpretation to evaluate how current law governs online content moderation, platform responsibility, and user safeguarding in online spaces like Roblox.

- Case Study Approach—Analysis of actual cases on Roblox, including failures in moderation, legal controversies, and difficulties in content management.

- Comparative Analysis—Analysis of content moderation on Roblox, TikTok, YouTube, and other platforms to identify best practices and regulatory loopholes.

- Engagement with Algorithmic Governance Theory—Drawing on the works of Rob Kitchin and Mireille Hildebrandt, this research critiques the deployment of AI as a regulatory tool and considers ethical implications in automated decision-making.

2. Contributions of the Study

2.1. Comprehensive Analysis of Moderation Systems

2.2. Evaluation of Legal Frameworks

2.3. Insights into Emerging Risks

2.4. Comparative Study of Moderation Practices

2.5. Recommendations for Policy and Practice

2.6. Contribution to Academic and Practical Discourse

3. Brief Overview of Roblox

4. Recent Incidents Highlighting the Risks in Roblox

4.1. Exposure to Inappropriate Content

4.2. Cyberbullying and Harassment

4.3. Predatory Behavior

5. Technical Aspects of Moderation in Roblox

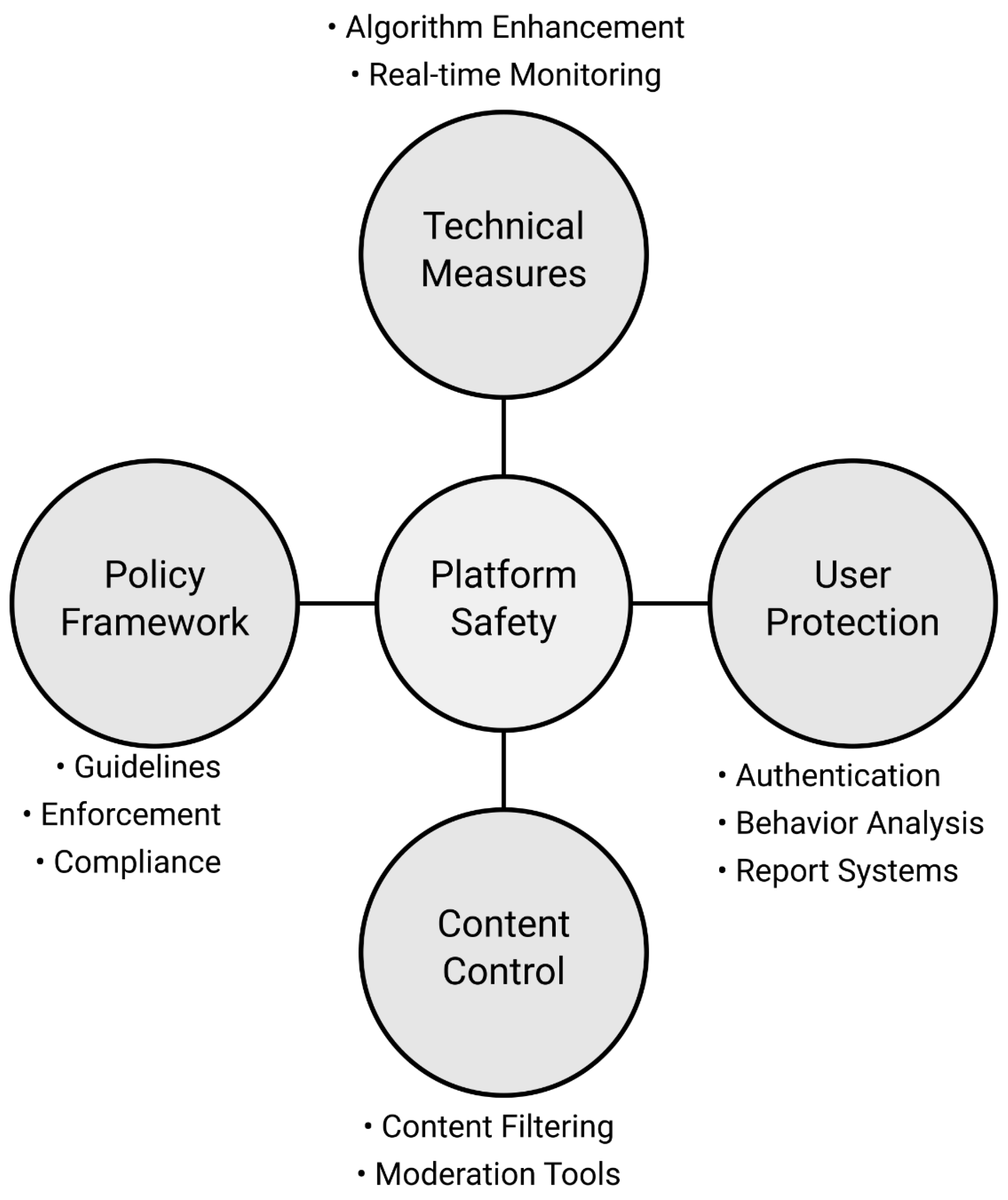

5.1. An Overview of Roblox’s Moderation System

5.2. Comparative Analysis of Moderation Systems in Roblox and Other Platforms

5.3. The Effectiveness and Challenges of AI in Roblox Content Moderation

5.3.1. Algorithmic Bias and the Issue of Fairness

5.3.2. Legal Accountability and Due Process in AI Moderation

- Obligations for VLOPs:

- Risk Assessment: VLOPs are required, according to Article 34(1) DSA, to conduct thorough assessments to identify and analyze systemic risks associated with their services, including the dissemination of illegal content, adverse effects on fundamental rights, and manipulation of services impacting public health or security.

- Risk Mitigation Measures: Based on risk assessments, VLOPs, per Article 35(1) DSA, must implement appropriate measures to mitigate identified risks. This includes adapting content moderation processes, enhancing algorithmic accountability, and promoting user empowerment tools.

- Independent Audits: Under Article 37 DSA, VLOPs are mandated to undergo independent audits to evaluate compliance with DSA obligations. These audits ensure transparency and accountability in the platforms’ operations.

- Data Access for Researchers: To facilitate public scrutiny and research, VLOPs, according to article 40 DSA, must provide data access to vetted researchers, enabling studies on systemic risks and the platforms’ impact on society.

- Implications for Roblox:

- Conduct comprehensive risk assessments related to content dissemination and user interactions (Article 34(1);

- Implement robust risk mitigation strategies, potentially overhauling existing content moderation systems (Article 35);

- Submit to independent audits, ensuring compliance with DSA mandates (Article 37);

- Provide data access to researchers, enhancing transparency and facilitating external evaluations (Article 40).

5.3.3. A Technical Fix Is Not Enough: The Need for Ethical and Regulatory Reforms

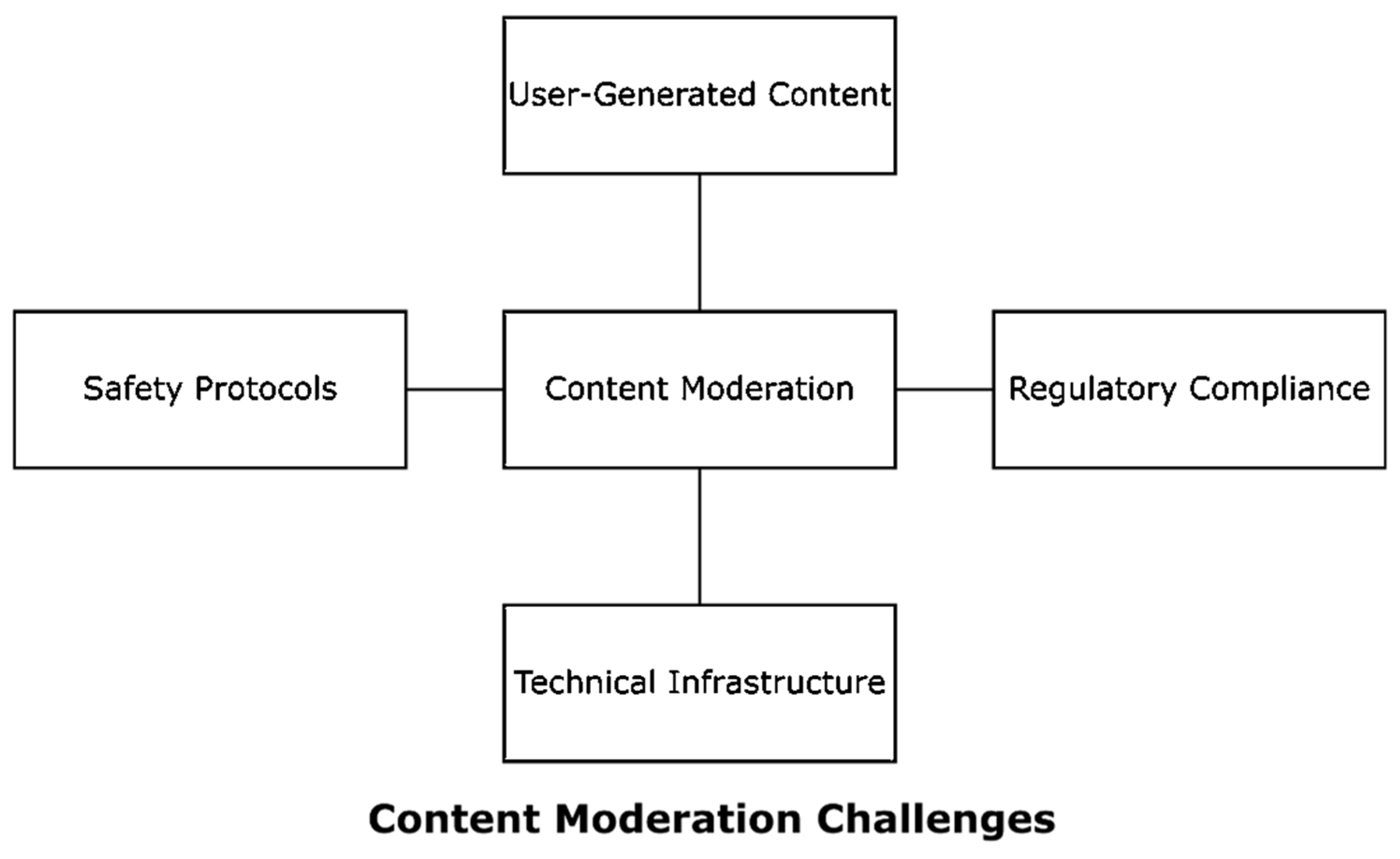

5.4. Moderation Challenges

6. Existing Legal Framework

6.1. United States

6.2. European Union

6.3. United Kingdom

7. Proposals for a New Legal Framework Applied in the Metaverse Platforms

7.1. Redefining Virtual Harm: Legal Protections in the Metaverse

7.1.1. GDPR and Paradox of Protecting Children in Platform Economics

- Verification Deadlock: Parental Consent vs. Privacy

- Children’s Datafication and Algorithmic Exploitation

- Behavioral profile-based content recommendations (usually automatic and non-transparent)

- Application of in-game marketing based on engagement metrics

- Targeted content filtering (e.g., for moderation of chat), potentially analyzing sensitive phrases

- Compliance Design Dilemma

- Limiting behavioral tracking by default

- Providing granular opt-ins (instead of opt-outs) for data gathering

- Turning off targeted content recommendations for minors in the absence of parental approval.

7.1.2. Digital Services Act (DSA): From Content Moderation to Systemic Risk Governance

- Systemic Risk Identification: From Damaging Games to Social Manipulation

- Breach of fundamental rights (such as freedom of expression, protection of minors)

- Recommender systems for manipulative purposes (e.g., sensationalist or harmful game amplification)

- Implications for social cohesion and mental health.

- Algorithmic Transparency and Research Access (Articles 42 and 40)

- Revealing whether harmful content is prioritized or deprioritized

- Error reporting rates for automatic flagging

- Providing authorized scientists with access to platform information.

- Human Empowerment, Rather than Just Protection

- Providing non-recommendation-based discovery choices (e.g., content organized by ratings or recency and not by likelihood of engagement)

- Providing mechanisms for kids and parents to appeal moderation choices through transparent, understandable channels

- Incorporating age-relevant explanation of algorithmic choices.

7.1.3. Section 230 CDA: Shield or Sword for Platform Inertia?

- Scope of Immunity: It is Strong but Not Absolute

- Vulnerable children who have been groomed, bullied, or exposed to adult content in Roblox have minimal legal remedies available against the site

- Roblox can moderate at will without suffering punishment for missing content or incorrect identifications.

- Whether Roblox’s game-creation platform and monetization features facilitate the creation of exploitative content

- Whether inaction in moderation can turn into enabling behavior, particularly whenever reported content is disregarded or recurrence is systematic.

- Good Samaritan Clause: Voluntary Protection, Rather Than an Obligation

- Platform Ethics vs. Legal Minimalism

- Emotional and Psychological Distress—Persistent cyber harassment, online grooming, and digital manipulation have a very detrimental psychological impact on victims, particularly children. These must be criminalized under cyber protection law (Citron 2014).

- Violations of Digital Identity—Exploitations of deepfakes, abuse of avatars, and online impersonations directly undermine a person’s digital life and autonomy and require greater legal recognition and enforcement capabilities (Floridi 2013).

- Reputational and Economic Harm—Current defamation law already safeguards against harm to reputation, and new frameworks need to be created to tackle virtual slander, doxxing, and financial exploitation in the Metaverse (Peloso 2024).

7.2. Ensuring Safe and Respectful Interactions in the Metaverse: The Need for Effective Consent Mechanisms

7.3. Navigating Jurisdictional Challenges in the Metaverse: The Need for International Cooperation and Legal Frameworks

7.4. Legal Subjectivity in Virtual Worlds: Avatars’ Status and Liability in Cyber Misbehavior

7.4.1. Should Avatars Have Legal Status?

- Enter contracts—A user’s avatar could purchase virtual goods, lease virtual property, or engage in smart contracts with legally recognized rights and obligations.

- Hold digital assets—As digital economies expand, avatars could be granted ownership rights over virtual property and NFTs, much like corporations possess assets.

- Be legally accountable—If avatars were granted legal personhood, they could be held liable for online harassment, digital fraud, or virtual trespassing, subjecting them to enforceable penalties.

7.4.2. Liability in Cases of Cyber Misbehavior: Users, Platforms, or Avatars?

- User Liability—In most legal systems, users are directly accountable for their online behavior. If a person engages in online harassment, fraud, or illicit transactions through their avatar, they can be prosecuted under existing cybercrime laws (Peloso 2024).

- Platform Liability—Platforms like Roblox, Meta, and Decentraland have partial legal immunity under laws such as Section 230 of the U.S. Communications Decency Act (CDA), which protects them from liability for user-generated content. However, emerging regulations like the EU Digital Services Act (DSA 2022) impose stricter responsibility standards. Platforms that fail to moderate harmful behavior may be held liable for facilitating digital misconduct.

- Avatar Liability?—Some scholars propose treating avatars as “digital agents”. If an avatar is involved in fraudulent contracts, virtual property theft, or harassment, legal frameworks could attribute liability to the avatar as a separate entity—like how corporations are held accountable independently of their owners (Floridi 2013).

7.4.3. The Role of Smart Contracts and Blockchain in Virtual Liability

- Reputation scoring systems—Avatars violating platform policies could have their digital reputation downgraded, limiting their access to specific virtual spaces.

- Token-based penalties—Virtual fines could be deducted from an avatar’s digital assets as an economic deterrent against misconduct.

- Contract enforcement mechanisms—If an avatar engages in fraudulent agreements, smart contracts could automatically execute restitution payments to affected parties.

7.4.4. Towards a Legal Framework for Virtual Personhood

- A tiered recognition system—Avatars used for personal interactions remain legally tied to users, while those engaging in commercial transactions or digital contracts have distinct legal identities.

- Mandatory avatar registration—Platforms could require avatars to be linked to verified user accounts to reduce the risk of anonymous misconduct.

- Hybrid liability frameworks—A balanced approach that combines user accountability, platform responsibility, and limited avatar legal personhood to ensure fair enforcement of virtual laws.

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arseneault, Louise, Lucy Bowes, and Sania Shakoor. 2010. Bullying victimization in youths and mental health problems: ‘Much ado about nothing’? Psychological Medicine 40: 717–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baszucki, D. 2021. The Metaverse Is the Future of Human Experience. Roblox Blog. [Google Scholar]

- BBC. 2022. Roblox: The children’s Game with a Sex Problem. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-60314572 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Bonagiri, Akash, Lucen Li, Rajvardhan Oak, Zeerak Babar, Magdalena Wojcieszak, and Anshuman Chhabra. 2025. Towards Safer Social Media Platforms: Scalable and Performant Few-Shot Harmful Content Moderation Using Large Language Models. arXiv arXiv:2501.13976. [Google Scholar]

- Citron, Danielle Keats. 2014. Hate Crimes in Cyberspace. Vol. 52, Osgoode Hall Law Journal. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dionisio, John David N., William G. Burns Iii, and Richard Gilbert. 2013. 3D Virtual worlds and the metaverse. ACM Computing Surveys 45: 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, Lisa. 2001. The Legal Ramifications of Virtual Harms. Master’s thesis, Vilnius University European Master’s Programme in Human Rights and Democratisation, Vilnius, Lithuania. [Google Scholar]

- Douek, Evelyn. 2021. Governing Online Speech: From ‘Posts-As-Trumps’ to Proportionality and Probability. Columbia Law Review 121: 759–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Yao, Thomas D. Grace, Krithika Jagannath, and Katie Salen-Tekinbas. 2021. Connected Play in Virtual Worlds: Communication and Control Mechanisms in Virtual Worlds for Children and Adolescents. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 5: 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Yogesh K., Laurie Hughes, Abdullah M. Baabdullah, Samuel Ribeiro-Navarrete, Mihalis Giannakis, Mutaz M. Al-Debei, Denis Dennehy, Bhimaraya Metri, Dimitrios Buhalis, Christy M. K. Cheung, and et al. 2022. Metaverse beyond the hype: Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management 66: 102542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2022. DSA Articles 17–20 on User Redress Mechanisms. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- European Commission. 2023. More Responsibility, Less Opacity: What It Means to Be a “Very Large Online Platform”—Statement by Commissioner Breton. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/STATEMENT_23_2452 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Filipova, Irina A. 2023. Creating the metaverse: Consequences for economy, society, and law. Journal of Digital Technologies and Law 1: 7–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, Joseph, John Torous, José Francisco López-Gil, Jake Linardon, Alyssa Milton, Jeffrey Lambert, Lee Smith, Ivan Jarić, Hannah Fabian, Davy Vancampfort, and et al. 2024. From “online brains” to “online lives”: Understanding the individualized impacts of Internet use across psychological, cognitive and social dimensions. World Psychiatry 23: 176–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridi, Luciano. 2013. The Ethics of Information. The Information Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Garon, Jon. 2022. Legal implications of a ubiquitous metaverse and a web3 future. SSRN Electronic Journal 106: 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, Tarleton. 2020. Content moderation, AI, and the question of scale. Big Data & Society 7: 205395172094323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, Tarleton. 2021. Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions That Shape Social Media. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Google. 2023. How Content ID Works. YouTube Help Center. Available online: https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2797370 (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Gorwa, Robert, Reuben Binns, and Christian Katzenbach. 2020. Algorithmic content moderation: Technical and political challenges in the automation of platform governance. Big Data & Society 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, Joanne E., Marcus Carter, and Ben Egliston. 2024. Content harms in social VR: Abuse, misinformation, platform cultures and moderation. In Governing Social Virtual Reality: Preparing for the Content, Conduct and Design Challenges of Immersive Social Media. Cham: Springer Nature, pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Keyan, Freeman Guo, and Hongxin Hu. 2024. Moderating embodied cyber threats using generative AI. arXiv arXiv:240505928. [Google Scholar]

- Guptaon, Ishika. 2024. Roblox Limits Meesaging for Under-13 Users Amid Safety Concerns. Available online: https://www.medianama.com/2024/11/223-roblox-limits-messaging-for-under-13-users-amid-safety-concerns/ (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Han, Jining, Geping Liu, and Yuxin Gao. 2023. Learners in the metaverse: A systematic review on the use of roblox in learning. Education Sciences 13: 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, Mireille. 2018. Algorithmic Regulation and the Rule of Law. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 376: 20170355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, Mireille. 2020. Law for Computer Scientists and Other Folk. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hinduja, Sameer, and Justin W. Patchin. 2024. Metaverse risks and harms among US youth: Experiences, gender differences, and prevention and response measures. New Media & Society, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hine, Emmie. 2023. Content moderation in the metaverse could be a new frontier to attack freedom of expression. Philosophy & Technology 36: 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEQE. 2025. Roblox: A Parents Guide to Protecting Children from Harmful Content. Available online: https://ineqe.com/2022/01/19/roblox-parents-guide-and-age-restrictions/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Jang, Yujin, and Youngmeen Suh. 2024. Cyber sex crimes targeting children and adolescents in South Korea: Incidents and legal challenges. Social Sciences 13: 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JetLearn. 2024. Roblox Statstics: Users, Growth and Revenue. Available online: https://www.jetlearn.com/blog/roblox-statistics#:~:text=Roblox%20has%20an%20estimated%20380,the%20United%20States%20and%20Canada (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Kang, Young-Joo, Ui-Jun Lee, and Saerom Lee. 2024. Who makes popular content? Information cues from content creators for users’ game choice: Focusing on user-created content platform “Roblox”. Entertainment Computing 50: 100697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karapatakis, Andreas. 2025. Metaverse crimes in virtual (Un)reality: Fraud and sexual offences under English law. Journal of Economic Criminology 7: 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Kang-Ho, and Dae-Woong Rhee. 2022. The necessity of content development research for metaverse creators—Based on the analysis of roblox and domestic academic research. Journal of Korea Game Society 22: 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Soyeon, and Eunjoo Kim. 2023. Emergence of the Metaverse and Psychiatric Concerns. Journal of the Korean Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 34: 215–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- King Law. 2025. Is Roblox Safe for Kinds? Available online: https://www.robertkinglawfirm.com (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Kitchin, Rob. 2017. Thinking critically about and researching algorithms. Information, Communication & Society 20: 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Yubo, and Xinning Gui. 2023. Harmful design in the metaverse and how to mitigate it: A case study of user-generated virtual worlds on roblox. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference. Edited by Daragh Byrne, Nikolas Martelaro, Andy Boucher, David Chatting, Sarah Fdili Alaoui, Sarah Fox, Iohanna Nicenboim and Cayley MacArthur. New York: ACM, pp. 175–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kou, Yubo, Yingfan Zhou, Zinan Zhang, and Xinning Gui. 2024. The ecology of harmful design: Risk and safety of game making on a metaverse platform. In Designing Interactive Systems Conference. Edited by Anna Vallgårda, Li Jönsson, Jonas Fritsch, Sarah Fdili Alaoui and Christopher A. Le Dantec. New York: ACM, pp. 1842–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, Harish. 2024. Virtual worlds, real opportunities: A review of marketing in the metaverse. Acta Psychologica 250: 104517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, Vidhya Lakshmi, and Mark A. Goldstein. 2020. Cyberbullying and Adolescents. Current Pediatrics Reports 8: 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langvardt, Kyle. 2020. Regulating Platform Architecture. Georgetown Law Journal 109: 1353–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Lik-Hang, Zijun Lin, Rui Hu, Zhengya Gong, Abhishek Kumar, Tangyao Li, Sijia Li, and Pan Hui. 2021. When creators meet the metaverse: A survey on computational arts. arXiv arXiv:2111.13486. [Google Scholar]

- Legal Information Institute. 2002. Ashcroft V. Free Speech Coalition (00-795) 535 U.S. 2002, vol. 234. Available online: https://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/00-795.ZO.html (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Livingstone, Sonia, and Amanda Third. 2017. Children and young people’s rights in the digital age: An emerging agenda. New Media & Society 19: 657–70. [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso, Ilaria, Antonio Messeni Petruzzelli, Umberto Panniello, and Chiara Nespoli. 2024. A microfoundation perspective on business model innovation: The cases of roblox and meta in metaverse. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 71: 12750–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, Vincenzo De, Qinke Di, Siyi Li, and Yuhan Song. 2024. The metaverse: Challenges and opportunities for AI to shape the virtual future. Paper presented at 2024 IEEE/ACIS 27th International Conference on Software Engineering, Artificial Intelligence, Networking and Parallel/Distributed Computing (SNPD), Beijing, China, July 5–7; pp. 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mozilla Foundation. 2022. YouTube Regrets Report. Available online: https://foundation.mozilla.org/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Mujar, Jose Miguel A., Denise Rhian R. Partosa, Leeann Kyle J. Porto, Derik Connery F. Guinto, John Roche Regero, and Ardrian D. Malangen. 2024. Perspective of senior high school students on the benefits and risk of playing roblox. American Journal of Open University Education 1: 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Nagyova, Iveta. 2024. Leveraging behavioural insights to create healthier online environment for children. European Journal of Public Health 34: ckae144.49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OFCOM. 2023. Online Safety Act 2023: OFCOM’s Powers and Enforcement Framework. UK Government. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2023/50 (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Park, Daehee, and Jeannie Kang. 2022. Constructing data-driven personas through an analysis of mobile application store data. Applied Sciences 12: 2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patchin, Justin, and Sameer Hindujaa. 2020. Tween Cyberbulling Report. Cyberbulling Research Center. Available online: https://www.developmentaid.org/api/frontend/cms/file/2022/03/CN_Stop_Bullying_Cyber_Bullying_Report_9.30.20.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Peloso, Caroline. 2024. The metaverse and criminal law. In Research Handbook on the Metaverse and Law. Edited by Larry A. DiMatteo and Michel Cannarsa. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 350–60. [Google Scholar]

- Reuters. 2024. UK Won’t Change Online Safety Law as Part of US Trade Negotiations. Reuters. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/uk-wont-change-online-safety-law-part-us-trade-negotiations-2025-04-09/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Roberts, Sarah T. 2019. Behind the Screen: Content Moderation in the Shadows of Social Media. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roblox Blog. 2021. Keeping Roblox Safe and Civil Through AI and Human Review. Available online: https://en.help.roblox.com/hc/en-us/articles/360029134331-Roblox-Blog (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Roblox Corporation. 2023. Roblox Transparency Report—Trust & Safety. Available online: https://corp.roblox.com/trust-safety/transparency-report-2023/ (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Roblox Corporation. 2024. Q4 Shareholder Letter. Available online: https://ir.roblox.com (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Roblox Corporation. 2025. About Us. Available online: https://corp.roblox.com/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Schulten, K. 2022. Roblox and the Risks of Online Child Exploitation. The New York Times, August 19. Available online: www.nytimes.com (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Shen, Haiyang, and Yun Ma. 2024. Characterizing the developer groups for metaverse services in Roblox. Paper presented at 2024 IEEE International Conference on Software Services Engineering (SSE), Shenzhen, China, July 7–13; pp. 214–20. [Google Scholar]

- Siapera, Eugenia. 2021. AI content moderation, racism and (de)coloniality. International Journal of Bullying Prevention 4: 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Shubham. 2025. How Many People Play Roblox in 2025. Available online: https://www.demandsage.com/how-many-people-play-roblox/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Solum, Lawrence B. 1992. Legal Personhood for Artificial Intelligences. North Carolina Law Review 70: 1231. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1108671 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- The Guardian. 2024. Pushing Buttons: With the Safety of Roblox Under Scrutiny, How Worried Should Parents Be? Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/games/2024/oct/16/pushing-buttons-roblox-games-for-children (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- The Jewish Chronicle. 2022. Children’s Game Roblox Features Nazi Death Camps and Holocaust Imagery. Available online: https://www.thejc.com/news/childrens-game-roblox-features-nazi-death-camps-and-holocaust-imagery-ddzzz1lg (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- TikTok. 2023. Transparency Report. Available online: https://rmultimediafileshare.blob.core.windows.net/rmultimedia/TikTok%20-%20DSA%20Transparency%20report%20-%20October%20to%20December%202023.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- UK Government. 2023. Online Safety Bill Factsheet. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/ (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Van Hoeyweghen, Sarah. 2024. Speaking of Games: AI-Based Content Moderation of Real-Time Voice Interactions in Video Games Under the DSA. Interactive Entertainment Law Review 7: 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yuntao, Zhou Su, Ning Zhang, Dongxiao Liu, Rui Xing, Tom H. Luan, and Xuemin Shen. 2022. A Survey on Metaverse: Fundamentals, Security, and Privacy. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 25: 319–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, Helen, Hamilton-Giachritsis Catherine, and Collings Beech. 2013. A review of online grooming: Characteristics and concerns. Aggression and Violent Behavior 18: 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wired. 2021. On Roblox, Kids Learn It’s Hard to Earn Money Making Games. Available online: https://www.wired.com/story/on-roblox-kids-learn-its-hard-to-earn-money-making-games/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- YouTube Help. 2023. Overview of Content ID. Available online: https://support.google.com/youtube/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Zhang, Zinan, Sam Moradzadeh, Xinning Gui, and Yubo Kou. 2024. Harmful design in user-generated games and its ethical and governance challenges: An investigation of design co-ideation of game creators on roblox. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 8: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Roblox | TikTok | YouTube | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Approach | Automated + human oversight | Aggressive AI + human review | AI tools + human evaluation | ML algorithms + Content ID |

| Key Tech |

|

|

|

|

| Human Role | Complex case review | Contextual review | Flagged content review | Appeals handling |

| Main Challenges | Real-time monitoring of interactive content | Over-moderation, cultural bias | Global censorship concerns | Inconsistent enforcement |

| Strengths | Youth safety focus | Quick removal | Fact-checking | Copyright protection |

| Content Focus | Games + chat | Short videos | Mixed media | Long-form video |

| Timing | Real-time | Pre/post posting | Continuous | Pre/post upload |

| Moderation Variable | Roblox | TikTok | YouTube |

| AI Sophistication (Gillespie 2020) | Uses automated filters for chat, text, and images; limited ability to detect contextual harm | Highly advanced computer vision and NLP-based AI, trained for detecting hate speech, nudity, and misinformation | Uses Content ID and deep learning AI for identifying copyright violations and harmful content |

| Human Oversight (Roberts 2019; TikTok 2023) | Moderators review flagged content, but response times are slow due to scale | Large-scale human moderation team ensures AI decisions are reviewed quickly | Uses hybrid moderation, but reviewers mainly focus on appeals rather than proactive monitoring |

| Effectiveness of AI (Douek 2021) | Often fails to detect coded or evolving harmful content; users bypass filters with modified language | Proactive moderation efficiently removes harmful videos before mass exposure | Effective for copyrighted content, but struggles with misinformation and algorithmic bias |

| Real-time Moderation (Roblox Corporation 2023; YouTube Help 2023) | Real-time AI filtering for in-game chat and user interactions | Automated removals happen within minutes, limiting content spread | Delayed removals—AI flags content, but human moderation is often required for final takedown |

| Regulatory Compliance (European Commission 2023; UK Government 2023) | Partial compliance with GDPR, UK Online Safety Act, and DSA but lacks clear transparency reporting | Highly compliant with the DSA and GDPR; has been fined for violations but improved disclosure | Complies with GDPR and DSA, but faces criticism for poor transparency in algorithmic decision-making |

| Transparency Mechanisms (TikTok 2023; Mozilla Foundation 2022) | Moderation decisions are opaque; lacks a clear appeals process for wrongful content removals | Provides detailed content removal reports, including policy rationale and country-specific enforcement | Transparency reports exist, but content removals are often inconsistent or politically contested |

| User Reporting and Appeals (European Commission 2022) | Users can report content, but appeal processes are slow and lack clarity | Users can appeal decisions, and TikTok has improved moderation response times | Users can dispute demonetization and content takedowns, but appeals take time |

| Handling of Virtual Harm (European Commission 2022) | Struggles to define ‘virtual harm’ legally; lacks mechanisms for addressing psychological distress and emotional harm | Has introduced psychological harm guidelines under EU DSA; enforces strict removal of harmful content | Limited focus on psychological harm, but misinformation regulation has improved |

| Platform Liability (European Commission 2022) | Claims Section 230 immunity in the U.S.; new regulations may force more accountability | Fined for AI failures in moderation but has proactive regulatory engagement | Criticized for evading liability under AI-driven content curation |

| Jurisdictional Framework | Legislative Instruments | Regulatory Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| United States | Child Pornography Prevention Act (CPPA), 1996

| Prohibition of virtual child exploitation content

|

| European Union | Council of Europe Convention on Cybercrime

|

|

| United Kingdom | Online Safety Act 2023 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chawki, M. AI Moderation and Legal Frameworks in Child-Centric Social Media: A Case Study of Roblox. Laws 2025, 14, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14030029

Chawki M. AI Moderation and Legal Frameworks in Child-Centric Social Media: A Case Study of Roblox. Laws. 2025; 14(3):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14030029

Chicago/Turabian StyleChawki, Mohamed. 2025. "AI Moderation and Legal Frameworks in Child-Centric Social Media: A Case Study of Roblox" Laws 14, no. 3: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14030029

APA StyleChawki, M. (2025). AI Moderation and Legal Frameworks in Child-Centric Social Media: A Case Study of Roblox. Laws, 14(3), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14030029