Between Urgency and Exception: Rethinking Legal Responses to the Ecological Crisis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Comparative Legal Analysis: This methodology was used to examine existing legal frameworks governing emergency governance, particularly the state of emergency and the state of exception, across different jurisdictions. The study contextualized climate emergency laws, public health emergency legislation (e.g., measures adopted during the COVID-19 pandemic), and national security exceptions to evaluate their applicability to environmental crises (Riaz et al. 2024).

- Case Study Approach: This study analyzed concrete instances where emergency measures have been applied to ecological crises, such as national climate emergency declarations and regulatory responses to extreme environmental disasters. These case studies helped identify the benefits, limitations, and risks associated with the implementation of exceptional legal measures to combat climate change.

3. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

3.1. Concepts

3.2. Natural Threats

4. The COVID-19 Public Health State of Emergency: A Legal and Institutional Precedent

4.1. The Pre-Existing Legislative Framework

4.2. Technical Mechanisms Available Before the Crisis

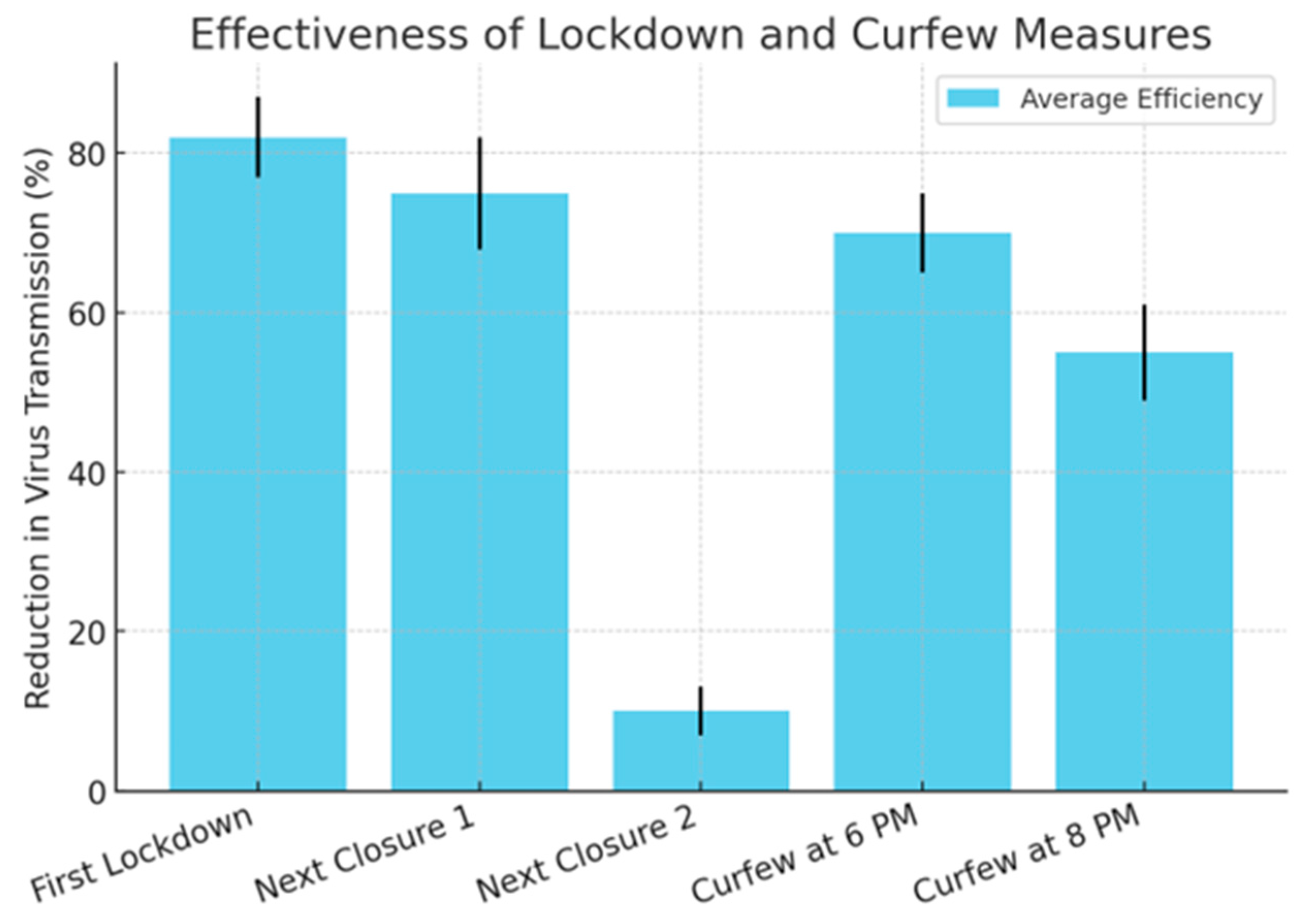

4.3. Assessing the Effectiveness of Exceptional Measures

4.4. The Limitations and Criticisms of the Public Health State of Emergency

- (1)

- Proportionality of Exceptional Measures

- (2)

- Impact on Fundamental Rights

- (3)

- Risks of Abuse and Normalization

- (4)

- Ethical and Social Justice Issues

5. The Potential Transposition of Lessons from the Public Health Emergency to the Ecological Emergency

5.1. The Characteristics of the Public Health Emergency Model

5.2. The Ecological Emergency: A Threat Comparable to a Public Health Crisis?

- (1)

- Similarities Between the Climate Emergency and a Public Health Crisis

- (2)

- Differences Between the Climate Emergency and a Public Health Crisis

- (3)

- Limitations of General Environmental Law in Addressing Ecological Crises

- Regulatory exemptions: Temporary waivers of certain administrative obligations to expedite reconstruction, as provided in Article L.152-4 of the Urban Planning Code.

- Financial assistance for affected communities and businesses: These funds support emergency response efforts, infrastructure reconstruction, and economic recovery in disaster-affected areas. Several types of aid can be provided, including grants to local authorities to repair damaged public infrastructure, such as roads, schools, sports facilities, and water and electricity networks. Financial support may also cover the securing of disaster-affected areas, including debris removal and the restoration of public spaces (Article L.1613-6 of the General Code of Local Authorities—CGCT)6. Businesses, particularly SMEs, may also receive specific financial aid in the form of exceptional grants provided by the State or local authorities to support the repair of their premises and the resumption of operations. They may also benefit from tax and social relief measures established under existing legislation. For instance, Article L.247 of the Tax Procedure Code (LPF)7 allows for such relief in cases of financial hardship or the inability to pay taxes. This provision could therefore be applied in the event of a natural disaster.

- 4.

- Tax relief measures: Businesses affected by environmental disasters may qualify for tax exemptions under Article L.247 of the Tax Procedure Code (LPF).

- 5.

- Accelerated compensation through the Cat-Nat regime: This mechanism ensures rapid financial assistance for victims of natural disasters, facilitating swift recovery and reconstruction.

6. Towards a Specific Legal Framework for Environmental Emergencies: Between Exception and Adaptation

6.1. An Environmental State of Exception: A Reactive but Risky Solution

6.2. Towards a Regulated Environmental Emergency Framework

- (1)

- A Dedicated Legal Framework for Environmental Emergencies

- (2)

- Enhanced Parliamentary and Judicial Oversight

- (3)

- A Public Consultation and Citizen Participation Mechanism

- (4)

- Time-Limited and Reversible Measures

- (5)

- A Dedicated Fund for Climate Emergency Measures

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ackerman, Bruce. 2006. Before the Next Attack: Preserving Civil Liberties in an Age of Terrorism. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Agamben, Giorgio. 2003. The State of Exception. In Homo Sacer. Paris: Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Alhoussari, Houda. 2025. Securing Health Data in the Digital Age: Challenges, Regulatory Frameworks, and Strategic Solutions in Saudi Arabia. Creative Publishing House 4: 2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autorité des marchés financiers (AMF). 2021. Report on Corporate Governance and Executive Compensation in Listed Companies. Paris: AMF. [Google Scholar]

- Basilien-Gainche, Marie-Laure. 2013. Rule of Law and States of Exception: A Conception of the State. Une Conception de l’État. Paris: PUF. [Google Scholar]

- Beaud, Olivier, and Claire Benoît Guérin-Bargues. 2018. The State of Emergency, a Constitutional, Historical and Critical Study, 2nd ed. Paris: LGDJ. [Google Scholar]

- Bigo, Didier. 2007. Exception and ban: About the ‘state of exception (Exception et ban: A propos de l’état d’exception). Erytheis. [Google Scholar]

- Bonneau, Thomas. 2020. Does Article 4 of Order No. 2020-321 of March 25, 2020 Temporarily Suspend Shareholder Rights? Paris: JCP E, p. 674. [Google Scholar]

- Bourg, Dominique, and Antoine Papaux. 2016. Dictionary of Ecological Thinking. Paris: PUF. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Chaltiel, Florance. 2020. About the State of Health Emergency, Text and Contexts. Paris: Lextenso. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Council of State. 1918. Arrêt Heyriès, June 28, 1918, Recueil Lebon. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/ceta/id/CETATEXT000007637204/ (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Couret, Alain, Daigre Jean-Jacques, and Barillon Barrillon. 2020. Assemblies and councils in crisis (Les assemblées et les conseils dans la crise). Paris Recueil Dalloz 13: 723. [Google Scholar]

- Dyzenhaus, David. 2006. The Constitution of Law. Legality in a Time of Emergency. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elmaghrabi, Mohamed, Ahmed Hassanein, and Diab Ahmed. 2025. How Do Firm-Level and Country-Level Sustainability Governance Shape Corporate Sustainability? Insights from Environmentally-Sensitive Industries. Leeds: Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Fales, David. 2024. French Taxation in 2024, 29th ed. Gualino: Lexteso. [Google Scholar]

- Ganser, Iris, Buckeridge Laura, Jane Heffernan, Mélanie Prague, and Rodolphe Thiébaut. 2024. Estimating the population effectiveness of interventions against COVID-19 in France: A modelling study. Epidemics 46: 100744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goupy, Marc. 2016. The State of Exception or the Authoritarian Powerlessness of the State in the Era of Liberalism. Paris: CNRS Éditions. [Google Scholar]

- High Committee on Corporate Governance (HCGE). 2020. Report of Nov. 6. 2020. p. 12. Available online: https://www.amf-france.org/sites/institutionnel/files/private/2020-12/rapport-rem-gouv-20201124_en.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Jamin, Christophe, Deny de Bechillon, and Marguenaud Jean-Pierre. 2010. Conference on “The Company and Fundamental Rights”. Cahiers du Conseil Constitutionnel. No 29. Available online: https://www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr/nouveaux-cahiers-du-conseil-constitutionnel/conference-sur-l-entreprise-et-les-droits-fondamentaux (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Jobert, Laurent, and Véronique Morel Joly. 2020. General meetings and board meetings put to the test by the epidemic. Paris. Review of Banking & Financial Law 90. (In French). [Google Scholar]

- Libchaber, R. 2023. Normative Destinies of an Overcome Crisis. Contracts Review 1: 159. (In French). [Google Scholar]

- Marine Pollution Response Plan. 2017. Available online: https://www.ecologie.gouv.fr/politiques-publiques/dechets-marins (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Mérieau, Eugénie. 2024. Geopolitics of the State of Exception: The Globalization of the State of Emergency. Paris: Le Cavalier Bleu. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry for the Economy and Finance. 2018. Exceptional Tax Measures for Disaster-Stricken Businesses in Aude. Paris: Directorate General of Public Finances. [Google Scholar]

- Molfessis, Nicolas. 2020. Le risque du Far West. La Semaine Juridique 13: 734–36. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Patrick, Ramesh Raja, Prabha Eswaran, Jamel Alzabut, and Gul Zaman Rajchakit. 2024. Modeling the dynamics of COVID-19 in Japan: Employing data-driven deep learning approach. International Journal of Machine Learning and Cybernetics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, Sébastien, Emmanuel Jouet, and Benoît Lioger. 2021. Urgence climatique et santé durable: Quel rôle pour un interniste? La Revue de médecine interne 42: 821–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paris Agreement. 2015. Adopted December 12, 2015, Entered into Force November 4, 2016. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Pellegrini, Bruno. 2005. La portée structurante des droits fondamentaux. VST-Vie Sociale et Traitements 2: 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report of the Public Health Ethics Committee. 2020. Commission on Ethics in Science and Technology. Public Health Ethics Framework: A Guide for Use in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Canada. 2nd Quarter 2020, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec. Available online: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/sites/default/files/covid/2958-enjeux-ethiques-pandemie-covid19.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Riaz, Muhammed, Khurram Shah, Imran Amacha, Thabet Abdeljawad, Asma Al-Jaser, and Mohammad Alqudah. 2024. A comprehensive analysis of COVID 19 nonlinear mathematical model by incorporating the environment and social distancing. Scientific Reports 14: 12238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudier, Karine, Albane Geslin, and David-Alexandre Camous. 2016. The State of Emergency. Courbevoie: Dalloz. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Bonnet, François. 2001. The State of Emergency. Paris: PUF. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Schwarze, Jürgen. 2009. European Administrative Law. Bruxelles: Bruylant. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Shah, X. 2007. The Theory of the State of Exception in Public Law. Paris: LGDJ. [Google Scholar]

- Sizaire, Vincent. 2020. A colossus with feet of clay—The fragile legal foundations of the health emergency. Human Rights Review. Rights & Freedoms News, March. (In French). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoclin-Mille, Céline. 2021. The state of health emergency will be extended until 1 June 2021. Dalloz actualité. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Territorial Climate-Air-Energy Plans (PCAET). 2024. Available online: https://www.finistere.gouv.fr/Actions-de-l-Etat/Environnement/Le-Plan-Climat-Air-Energie-Territorial-PCAET (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- The National Climate Change Adaptation Plan (PNACC). 2024. Available online: https://www.adaptation-changement-climatique.gouv.fr/comprendre/strategie/plan-national-dadaptation0? (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Troper, Michel. 2011. Law and Necessity. Coll. Leviathan. Paris: PUF. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Tushnet, Mark. 2005. Emergencies and the Idea of Constitutionalism. The Constitution in Wartime. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Impact Study, Bill Extending the Public Health State of Emergency and Supplementing Its Provisions, 2 May 2020, and Opinion, Emergency Law Bill to Address the COVID-19 Epidemic, Senate, March No. 380, 9, 2020. |

| 2 | Regulation (EU) 2021/1119 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 June 2021, establishing the framework required to achieve climate neutrality and amending Regulations (EC) No 401/2009 and (EU) 2018/1999 (“European Climate Law”). |

| 3 | Decree no. 2024-530 of 10 June 2024 adopting the national strategy for the sea and the coast, JORF no. 0135 of 11 June 2024, Text no. 13. |

| 4 | The Environmental Code, 2025, France. |

| 5 | Information Report No. 603 (2023–2024), Submitted on 15 May 2024, Natural Disaster Compensation Scheme, Senate, France. |

| 6 | The General Code of Local Authorities, 2025, France |

| 7 | The Tax Procedure Code (LPF), 2024, France. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alhoussari, H. Between Urgency and Exception: Rethinking Legal Responses to the Ecological Crisis. Laws 2025, 14, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14020026

Alhoussari H. Between Urgency and Exception: Rethinking Legal Responses to the Ecological Crisis. Laws. 2025; 14(2):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14020026

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlhoussari, Houda. 2025. "Between Urgency and Exception: Rethinking Legal Responses to the Ecological Crisis" Laws 14, no. 2: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14020026

APA StyleAlhoussari, H. (2025). Between Urgency and Exception: Rethinking Legal Responses to the Ecological Crisis. Laws, 14(2), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws14020026