1. Introduction

Insolvency often used to mean the end for companies. Modern insolvency laws place restructuring at the forefront or at least offer it as an equivalent alternative to liquidation. Restructuring is not only in the interests of the entrepreneur and the economy as a whole, because jobs are retained, but also in the interests of the creditors, because the share of the proceeds to creditors is in most cases comparatively much higher. Ultimately, it is also in the interests of the debtor’s contractual partners, because the contractual relationships can be maintained.

Insolvency laws in many European countries have been innovative, especially recently. The somewhat older reform in Germany (creation of a new insolvency law—InsO) and the one in France (Pacte Law) can be highlighted. These reforms aimed to facilitate the restructuring of insolvency proceedings.

The legal situation in Europe before COVID-19 and the PR directive (PRD) adoption was not very friendly to restructuring and the economy because it hardly provided any possibility of restructuring an insolvent company. Regulation in Europe was no longer up-to-date and no longer corresponded to the European benchmark. In this context, there was a necessity for “early warning systems” and “restructur-ing-friendly legal environment” (

Stanghellini et al. 2018, p. 26).

The current PRD largely reforms corporate insolvency law. Instead of proceedings that no longer meet the requirements of the present, a uniform insolvency procedure will be created, rendering insolvency proceedings more efficient while also ensuring “a predictable and fair distribution of recovered value among creditors” (

European Parliament 2023, p. 1). The focus is on making it easier to restructure companies. For this reason, regulation in the EU member states should become more attractive and the restructuring plan should become a modern instrument, thus enabling the debtor to make a fresh economic start. To largely reduce the stigma of bankruptcy and insolvency, the debtor should be able to achieve restructuring proceedings by applying for a restructuring plan before the insolvency proceedings are opened.

The objective of this paper is to examine and compare corporate insolvency laws in the US, England, France, and Germany, focusing on the functional differences and legislative adaptations influenced by the EU directive 2019/1023 on preventive restructuring frameworks. By examining the directive’s impact on creditor classification and procedures, as well as the debtor-friendly and creditor-friendly approaches in the selected jurisdictions, this study highlights key divergences and similarities. Ultimately, this article aims to provide insights into the international dimensions of corporate insolvency law and offer informed legal recommendations.

To adopt a comparative approach to corporate insolvency law in the selected jurisdictions, the first step is a critical analysis of directive (EU) 2019/1023 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on preventive restructuring frameworks, debt discharge, and disqualifications, and measures to increase the efficiency of procedures related to restructuring, insolvency, and discharge of debt, while amending directive (EU) 2017/1132 (

European Parliament 2019). The second step is the analysis of the current corporate insolvency law systems of the selected jurisdictions, identifying their main objectives and subsequently comparing them. The impact of the PRD on each legal system will also be emphasized. Therefore, in this comparative approach, the functional perspective will prevail, starting with a regulatory issue that will be analyzed further on in each selected jurisdiction. This analysis involves several steps: first, a presentation of the regulation in each selected jurisdiction, and second, an evaluation of how that issue is addressed in each particular country.

The author intended to offer a comprehensive analysis of corporate insolvency laws with a focus on the advantages and disadvantages of each selected jurisdiction. In addition, the countries were not randomly selected. Rather, the rationale behind the discussion on jurisdictional proceedings had in view the fact that all of them have diverse legal traditions. Thus, France and the US have similar legal views on the analyzed subject; meanwhile, the UK, despite being a former member state of the European Union, is still concerned with the harmonization of its regulations with the EU, and is also, to a certain level, similar to Germany in its legislative approach on the analyzed subject. Also, all four jurisdictions have highly influenced the PR directive, and their regulations on corporate in-solvency are considered as leading the global quest for the perfect insolvency and/or restructuring regimes concerning corporate debtors under financial hardship. This article contributes to the field through a functional approach and a comparative perspective, through detailed and helpful information on the characteristics of the relevant different regulations in the selected EU member states, the UK, and the US.

2. Formation of Creditor Classes Under Directive 2019/1023/EU

To ensure the smooth functioning of the internal market and that fundamental freedoms such as the freedom of establishment and freedom of movement of capital are respected, the EU feels obliged to remove existing obstacles in this regard. One of these obstacles is that there is a great divergence between the member states about preventive restructuring options and insolvency regulations.

Directive (EU) 2019/1023 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on preventive restructuring frameworks, on the discharge of debt and disqualifications, and on measures to increase the efficiency of procedures concerning restructuring, insolvency, and discharge of debt, and amending directive (EU) 2017/1132 (directive on restructuring and insolvency), aim to remove such obstacles and to ensure that viable companies and entrepreneurs in financial difficulties have access to effective preventive restructuring measures that enable them to continue operating, but also to offer over-indebted companies a debt relief option. It also aims to create more efficient restructuring, insolvency, and debt relief through shorter procedure times and lower costs.

Now that we have outlined the general objectives of the directive, namely efficiency, flexibility, and the reduction of costs and delays, we can now examine a key mechanism which, according to the drafters of the directive, is intended to make it possible to implement these objectives: the creation of classes of creditors, which will be further analyzed.

The directive already states in its recitals that member states should be given the flexibility to apply common principles and to adapt national legal systems. Member states should also be able to maintain or introduce preventive restructuring frameworks other than those provided in the PRD. Through a series of opening clauses, the directive grants member states a great deal of flexibility in implementation. According to article 2 of the directive, important terms such as “insolvency”, “likely insolvency”, and “SME” are to be interpreted following the national law. The directive only sets minimum standards for the content of restructuring plans and for the design of the class system. The criteria to be used for the comprehensible allocation of a creditor to a specific class are left to the member states and should be of no importance, among other things, for creditors who are only partially secured, according to Recital 43 (

European Parliament 2019).

The obligation to divide the affected parties into classes applies in principle to all companies subject to the directive. However, according to article 9 paragraph 4 subparagraph 3 of the directive, member states are free to exempt SMEs from the obligation to form classes (

European Parliament 2019). This is justified by the relatively simple capital structure of these companies. If SMEs form only one voting class and this class votes against the adoption of the restructuring plan, the SMEs must be allowed to submit a new plan according to Recital 4 (

European Parliament 2019).

The formation of creditor classes is intended to ensure that creditors with similar rights are treated fairly and that the rights of the parties concerned are not unduly influenced when the restructuring plans are adopted. The allocation of creditors should consider the rights and ranking of the claims or the interests of the parties concerned, when the respective plan is adopted. Member states must ensure that more than two classes of creditors can be formed. The introduction of different classes of creditors for secured, unsecured, and subordinated claims should be possible. If there is insufficient common interest in the allocation of classes, the separate formation of classes should also be available for these creditors, for example, tax authorities and social security institutions, as stated in Recital 44 (

European Parliament 2019).

Parties concerned. Article 2 paragraph 1 (2) of the directive defines the affected parties as those creditors or classes of creditors whose claims or interests are directly affected by a restructuring plan (

European Parliament 2019). National law can provide that employees and shareholders are also considered affected parties. The affected parties must also be distinguished from the so-called affected parties according to article 11 of the directive. When using the preventive restructuring framework, the restructuring plan must be submitted to the affected parties for acceptance. Only the parties affected by a restructuring plan and the employees should be able to vote on the acceptance of a restructuring plan. National law can provide the opportunity for shareholders to vote. However, they can also be excluded from the right to vote despite the possible impact on their interests. In any case, participation in the acceptance procedure for restructuring plans is not provided for creditors who are not affected by a restructuring plan. Nor should their support be required for the plan to be accepted, according to Recital 43 (

European Parliament 2019) Regardless of the possible impact, certain parties can be excluded from the right to vote. Member states may provide for this under article 9(3) (a) to (c) of the directive for the following parties: shareholders; creditors whose claims are subordinated to the claims of ordinary unsecured creditors following the normal order of priority in liquidation, and any party closely associated with the debtor or the debtor’s company who is in a conflict of interest under national law (

European Parliament 2019).

Not every claim automatically leads to being affected by the restructuring plan and to the possibility of participating in the voting procedure. Some claims, from the outset, can be excluded from the restructuring plan by the member states because of their importance to the creditors. According to article 1 paragraph 5 of the directive, member states can exclude certain employee and maintenance claims, as well as claims arising from the debtor’s tortious liability, from the restructuring plan. Article 1 paragraph 6 of the directive excludes claims to accrued occupational pension entitlements (

European Parliament 2019).

The directive merely contains a legal definition of the term restructuring. This includes, for example, in art. 2 para. 1 (1): “(…) include changing the composition, conditions or structure of a debtor’s assets and liabilities or any other part of the debtor’s capital structure, (…)” (

European Parliament 2019). This includes the sale of assets, business units, or the company as a whole. When implementing the directive, the member states can decide for themselves how to deal with measures other than those laid down in the regulation. However, deferrals of claims are not explicitly mentioned in the directive.

The PRD does not refer anywhere to a “minimum level of impact” to be able to vote on the plan as an affected party. In my opinion, it can therefore be assumed that any measure taken in the restructuring plan that hinders the timely and complete settlement of creditors’ claims will affect the respective creditor or shareholder, and thus also lead to a deferral of claims.

Cases in which affected parties do not participate in the voting process are problematic (see in this respect, for instance, the

Purdue Pharma case from the US, where “the nearly 60,000 personal injury claimants who cast votes overwhelmingly approved of the plan, but almost 69,000 claimants did not cast votes” (

Jacoby 2023, p. 1323) and also

In the Boy Scouts of America bankruptcy, where more than 82,000 persons filed abuse claims but “less than 57,000 cast a vote and of that number, more than 8000 voted against the plan that cut off their rights against the debtor as well as a huge number of non-debtors” (

Jacoby 2023, p. 1322)). There are cases in which the restructuring plan was sent to the affected parties per article 10 paragraph 2 letter c of the PRD, but they did not participate in the vote on the adoption of the restructuring plan. The plan is binding for the affected creditors involved in the adoption (

European Parliament 2019). In any case, those who were properly notified are considered to be included. According to article 15 paragraph 2 of the PRD, the member states must ensure that creditors who were not involved in the adoption of the plan are not affected by the plan (

European Parliament 2019). However, this presumably only refers to those creditors who did not participate in the vote despite being summoned. Ultimately, however, according to Recital 64, it is up to the member states to decide how to deal with creditors who were properly summoned but did not attend the vote (

European Parliament 2019).

Debtors should be able to satisfy claims of non-affected parties and claims from affected creditors arising during the suspension of individual enforcement measures in the ordinary course of business, as Recital 39 suggests (

European Parliament 2019).

Common interest criterion for the allocation of creditors. The PRD does not provide an explanation or definition of the concept of ‘common interest’. It is up to the member states to decide how narrowly the common interest of creditors is interpreted. For example, states could decide to divide creditors with essentially the same interests into several groups. In addition, the debtor can also influence the allocation of creditors. Under the PRD, the debtor may influence the separation of creditors with essentially the same interests. This could also lead to an obvious advantage or disadvantage for creditors, as we shall see later on.

The main criterion for allocating the parties concerned to the creditor classes to be formed is the existence of common interests. These common interests must be sufficiently present per article 9(4) sentence 1 of the directive. In any case, no common interests are assumed in article 9(4) sentence 2 of the directive for creditors with secured and unsecured claims. Within a class, creditors with sufficient common interests are to be treated equally and in proportion to their claims per article 10(2)(b) of the directive. According to Recital 44, if certain creditors, such as tax authorities or social security institutions, lack a sufficient degree of common interests, member states may require the formation of separate classes for them (

European Parliament 2019).

The common interest criterion is impossible to ignore when allocating creditors to classes. Ultimately, the approval of a restructuring plan is the responsibility of the judicial and administrative authorities. According to article 10 paragraph 2 letter b of the PRD, these authorities must only approve it if creditors with sufficient common interests in the same class are equal and proportionate to their claims (

European Parliament 2019). This requirement must always be checked. If creditors with the same interests are treated in separate classes and there are no objectively identifiable and understandable reasons for this separation, the judicial or administrative authority must refuse to confirm the restructuring plan.

The criterion of common interest should not be confused with the criterion of the “best-interest of creditors”, which can be found in article 2 paragraph 1 item 6 of the PRD (

European Parliament 2019). This plays a central role in the cross-class cramdown.

Classification into creditor classes. The PRD requires, as a minimum, the separation of creditors with secured and unsecured claims for the formation of classes according to art. 9 para. 4 sentence 2 (

European Parliament 2019). In addition, the PRD in Recital 44 and article 9(4) makes some suggestions for the division into further separate classes, including classes for creditors with subordinated claims, tax authorities, social security institutions, employees, and vulnerable creditors such as small suppliers (

European Parliament 2019). Whether separate classes are formed for shareholders is within the competence of the member states according to Recital 43 (

European Parliament 2019). The member states must ensure that, when classes are formed, vulnerable creditors receive sufficient protection as stipulated by art. 9 para. 4, subpara. 4 (

European Parliament 2019). The directive itself does not contain any further requirements for the content of the classes for creditors with secured or unsecured claims. Nevertheless, the classes with secured and unsecured claims and the allocation of creditors to the two classes are examined in more detail below.

Creditors with secured claims. The PRD requires that secured claims be classified in a separate class. However, neither the PRD nor the recitals provide any further details as to which exact secured claims fall into this class. It is up to the member states to create rules to classify secured claims based on an assessment of the collateral.

Recital 44 states that claims can be divided into secured and unsecured parts (

European Parliament 2019). The secured part of the claim is allocated to the class for secured claims. The unsecured part is then allocated to a class for unsecured claims. In a preventive restructuring procedure, a class for secured creditors only needs to be formed if the secured claims will also be affected by the restructuring plan. The claim is affected by the restructuring plan if it is either reduced or deferred. However, if the secured claims can be met and/or the debtor entirely excludes creditors with secured claims from the restructuring plan, the formation of a separate class is not required.

It remains questionable whether and to what extent the inclusion of secured creditors in the restructuring plan is reasonable or justified at all. After all, the claims of those creditors are (largely) secured by default. They should therefore in principle be fully satisfied. However, secured creditors are protected at least up to the value of their security, and with this amount, they fall into the class of secured creditors. If the secured claim is reduced or curtailed, the part of the claim not covered by the security will have to be satisfied in the class for unsecured claims. A reduction below the amount of the security could ultimately mean a disadvantage for the secured creditors as a result of the restructuring process. Secured creditors could get out better in insolvency proceedings than in restructuring proceedings and would therefore refuse to consent to the restructuring plan.

Creditors with unsecured claims. The class of unsecured claims therefore includes all claims not secured by the deposit of assets. All unsecured claims for which separate classes are not established can, in principle, be included in this class. The PRD dispenses with a further subdivision of unsecured creditors according to their respective interests and leaves the division of unsecured creditors into one or more classes to the implementation of the member states. The PRD itself only speaks of various other classes of unsecured creditors, classes of creditors with subordinated claims, and classes for creditors in particular need of protection such as small suppliers. Unsecured parts of partially secured claims will in any case fall into this group, as Recital 44 stipulates (

European Parliament 2019). One should also note here that a class for unsecured claims should only be created if a reduction in unsecured claims is provided for in the respective restructuring plan according to article 8 paragraph 1 letter d (

European Parliament 2019).

Employees and shareholders. Two special positions in terms of being affected by restructuring measures are employees in their capacity as creditors and shareholders as participants in the company being restructured. According to article 2 paragraph 1 (2) of the PRD, employees and shareholders in their capacity as creditors are generally considered to be affected parties, provided that this is provided for in national law after the directive has been implemented (

European Parliament 2019).

It is up to the member states to exclude the employee claims from the preventive restructuring framework. If employees are not involved or if they are explicitly excluded from the restructuring process, they are not considered affected parties, and their claims must be fully met, as stipulated by Recital 43 (

European Parliament 2019). If employees are treated as affected parties in the restructuring plan, a separate class can be created for them according to art. 9 para. 4 sentence 2 (

European Parliament 2019). The individual and collective rights of employees under Union labor law and the national law of the member states must not be affected by the directive and must be guaranteed to employees throughout the restructuring process. This includes,

inter alia, the right to collective bargaining and industrial action. Both employees and employee representatives must be informed and consulted about the decision to use a preventive restructuring procedure. Employees and their representatives must be provided with information that enables them to examine the proposed restructuring plan. To meet employees’ right to enforce their claims, the directive contains two scenarios, the choice of which is left to the member states. On the one hand, Recital 61 states that unmet employee claims could be excluded from a suspension of individual enforcement measures, or, on the other hand, employee claims could generally be excluded from the scope of the preventive restructuring framework and subject to protection under national law (

European Parliament 2019).

Concerning shareholders, it is also up to the member states whether they, as affected parties, should have the opportunity to vote on a restructuring plan or not. According to article 12 paragraphs 1 and 2 of the directive, the member states must primarily ensure that shareholders cannot unjustifiably prevent, obstruct, or delay the adoption, confirmation, or implementation of restructuring plans (

European Parliament 2019). This could be achieved, for example, by excluding shareholders from the voting procedure, in which case no separate class would have to be formed for them. However, according to article 9 paragraph 3 letter a of the directive, the member states can also provide that shareholders have no right to vote, regardless of whether they are affected by the measures of the restructuring plan. If shareholders are involved in the voting process, their rejection of the plan could be reviewed by a judicial or administrative authority and their approval could be replaced by a cross-class cramdown (

European Parliament 2019). If there are different shareholdings in a company, shareholders can be divided into several classes according to Recital 58 (

European Parliament 2019). The PR directive also mentions in the recitals the possibilities for setting corporate law measures to support the restructuring of the company. Reference is also made in Recital 2 to the possibility of converting the company’s liabilities into equity (so-called debt-equity swaps) (

European Parliament 2019).

From the considerations previously raised, it appears that member states will have to integrate into their judicial reorganization procedures (i) a minimum of two classes of creditors, except for SMEs for whom it is possible to keep only one class; (ii) a procedure allowing the judge to control plans according to “the best interests of creditors”; (iii) a control by the judge relating to the possibility for the company to avoid insolvency by applying the plan it submits; and (iv) a cross-class forced application procedure.

Teti et al. (

2024) assess the effectiveness of the EU directive on restructuring and insolvency law, confirming that “companies successfully undergoing a preventive restructuring procedure showcase higher survival rates, albeit coupled with weaker financial performances when compared to their counterparts undergoing the traditional bankruptcy process” (

Teti et al. 2024, p. 79). In addition, the PRD is seen as “a tool to facilitate a going-concern rehabilitation of the business and to grant the debtor a second chance for the benefit of value-maximization” (

Ehmke et al. 2019, p. 184).

Cavallini and Gaboardi, considering the position of vulnerable creditors as well as the economic impact of the PRD, state that “the preparation of a preventive restructuring framework reveals itself suitable for creating an economic result which, by preventing the debtor’s failure, can ensure also the protection of weak creditors from the negative financial consequences that the persistence (and the natural worsening) of the debtor’s financial distress tends to engender. From this point of view, therefore, the restructuring can lead to a result that, in terms of economic efficiency, produces more value than that which the redefinition of the conditions of satisfaction of the creditor class and, in general, of interested parties inevitably destroys” (

Cavallini and Gaboardi 2023, pp. 89–90).

All in all, the European harmonization of restructuring and insolvency law is definitely a process that will develop in time and that will tend to “be gradually defined through consequential stages, one more articulated and penetrative than the one which proceeded but, above all, more invasive in its plan for shaping national insolvency laws” (

Cavallini and Gaboardi 2023, p. 25). Summing up, the PRD does not impact directly the content of national laws; rather, it favors them towards better coordination regarding cross-border insolvency. After analyzing several important aspects of the PRD, the author concludes that, despite the jurisdictional divergences, the directive intends to make insolvency regimes more efficient, cost-effective, and legally secure, while balancing the creditor’s and debtor’s interests. Indeed, due to the PRD, European legal systems started to transition from a creditor-oriented regulation regime toward a more debtor-focused approach, having as its main aim the prevention of financial distress and the facilitation of agreements with creditors. The most important message that the PRD transmits is, in the author’s opinion, that each jurisdiction, before and while embarking on insolvency reforms to increase their attractiveness of reorganization procedures, needs to also focus on improving their restructuring ecosystem, and by this I refer to a developed and marketable institutional environment to deal with financial distress of companies.

3. Differences and Similarities in Their Conceptual Framework

Corporate debtors who experience financial distress with a higher or lower impact on the company are regulated in different jurisdictions either by different statutes or by the same statute, usually on multiple chapters, as we shall see further on. Despite the differences, there is one major similarity, namely the clear distinction made by each jurisdiction regarding the procedure aiming at reorganization and aiming at the liquidation of a company. In this respect, the US Bankruptcy Code (Title 11) regulates liquidation in Chapter 7 and restructuring in Chapter 11. Under Chapter 7, “a debtor undertakes an accounting of all of their personal assets, interests, and debts and then liquidates said assets and interests until either the debt is paid off or the debtor has no unprotected assets remaining”, (

Ritter 2024, p. 2). It should also be noted that the same debtor retains “all assets gained after the commencement of the case, which is said to be at the time of the initial filing” (

Ritter 2024, p. 2). Also, today’s US reorganization procedure is regulated in the United States Code, Title 11 Chapter 11 (reorganization). At its core lies the reorganization plan prepared by the debtor under an automatic stay, which categorizes the claims of creditors and shareholders into distinct classes. The plan must be approved by two-thirds of the creditors’ claims in each class and by a majority of the creditors according to U.S. Code § 1126 (c). If the plan of reorganization is not accepted by all classes of creditors, it can still be confirmed by the court in a cramdown according to Chapter 11 of the U.S. Code § 1129 (b), provided that the dissenting classes are not placed in a worse position than they would be in the liquidation scenario (

de Weijs et al. 2019;

Seymour and Schwarcz 2021;

McCarthy 2020).

In line with Chapters 7 and 11 of the US Bankruptcy Code mentioned above, Insolvenzordnung (insolvency code, ‘InsO’) is the main regulation in Germany, which has been in force since 1999, adapting both liquidations (Pars 1 to 5 of the InsO) and restructuring (Parts 6 and 7, Sections 217–269 of the InsO). The Insolvency Ordinance (InsO) (

Federal Ministry of Justice 1999) of 5 October 1994 replaced the Bankruptcy Ordinance (KO), the Settlement Ordinance (VglO), and the General Enforcement Ordinance (GesO) that had been in force until then, on 1 January 1999. In addition to this, in the context of COVID-19, due to financial and economic disarray, in order to protect corporations, regulations in this area of restructuring and mainly pre-insolvency in Europe became many-sided, mainly as a consequence of the adoption of the “European Restructuring Directive” (2019), which highly impacted all European member states, and even countries that are not EU members, such as the United Kingdom (

Bork 2021). In this context, the preventive restructuring framework was implemented in Germany through “The new Act on the Stabilization and Restructuring Framework for Companies” (SanInsFo). The government proposal was published on 14 October 2020 and was approved by the Bundestag on 17 December 2020. The SanInsFoG then came into force on 1 January 2021. The core component is the StaRUG, as outlined in art. 1 of SanInsFoG, which provides for the implementation of the preventive restructuring framework for businesses in a separate law. Scholars consider that the core element of StaRUG is “the restructuring plan, which is prepared by the debtor and submitted to its creditors for approval. This plan can be used to compromise any form of debt as well as to modify equity and rights in collateral, including collateral provided by associated companies” (

Ghio et al. 2021, p. 440). The SanInsFoG also makes numerous changes to the insolvency law, changes that will not be discussed in more detail here.

The regulations on restructuring are multifaceted in the United Kingdom too, being made up of several acts, namely the Insolvency Act 1986, which set up a liquidation and restructuring framework in three of its parts: Part IV “Winding Up of Companies Registered under the Companies Acts” (liquidation), Administration (“Schedule B1”), and Part I “Company Voluntary Arrangements” (CVA) (restructuring). Apart from these regulations, in The Companies Act 2006, Part 26 and Part 26A, there is also the “Scheme of Arrangement (SoA)” which can be used “ante” and “post” insolvency. However, it should also be mentioned that the British Scheme of Arrangement was inspired by the US Chapter 11 procedure, although to a lesser extent than other regulations from around the world.

Later on, on 26 June 2020, due to the adoption of the “European Restructuring Directive” (2019), although no longer a member of the EU, the UK adopted “the Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act 2020” (CIGA 2020), which “entails several elements largely reflecting the provisions of the directive, possibly to defend its position within the ongoing institutional competition with other European countries” (

Ghio et al. 2021, p. 440). According to

Walton and Jacobs (

2022), CIGA 2020 introduced three main measures: (1) a new restructuring mechanism known as a restructuring plan (RP) under Part 26A of the “Companies Act 2006” (

Parliament of the United Kingdom 2006); (2) the Company Moratorium under Part A1 of the Insolvency Act 1986, and (3) the Suspension of Termination (ipso facto) clauses, falling under Section 233B of the Insolvency Act 1986, which “provides that any provision that allows for the termination of a contract for the supply of goods and services or for a party to do ‘any other thing’ when a counterparty enters into a relevant insolvency procedure ceases to apply once the counterparty enters into that relevant insolvency procedure” (

Sarra et al. 2022, p. 56).

As far as France is concerned, the French bankruptcy framework is also diversified. Insolvency and restructuring are regulated by Book 6 of the Code de Commerce, these proceedings being either court-supervised (

Vessio 2022) or on the contrary, involving a minimal court involvement or even an out-of-court path (

Stef and Bissieux 2022). The French legislator adopted the pre-insolvency process, introduced only recently by the European directive, in 1984 (Law No. 84-148, 1984). Thus, the French preventive restructuring regime “is a comprehensive body of law, with no less than five pre-insolvency procedures: (i) ad hoc mandate (mandat ad hoc); (ii) conciliation (conciliation); (iii) safeguard (sauvegarde); and its two variants, (iv) accelerated financial safeguard (sauvegarde financière accélérée) and (v) accelerated safeguard (sauvegarde accélérée)” (

Ghio 2021, p. 3).

It should be noted that in the face of these very precise and general guidelines, article 196 of the PACTE law no. 2019-486 of 22 May 2019, which empowered the French Government to adopt measures aimed at making the provisions of book VI of the commercial code with the PRD, retained a narrower domain. This minimum transposition is in fact centered on procedures—and particularly accelerated safeguard—comprising committees of creditors, which are replaced by the system of classes of creditors and, more generally, by the classes of “affected parties”. Following the report to the President of the Republic on reform ordinance No. 2021-1193 of 15 September 2021, given the diversity of preventive and curative procedures offered by Book VI of the Commercial Code, “It did not appear necessary to call into question its general architecture, but rather to guarantee the readability of the law by retaining, as far as possible, the provisions whose modification is not useful for transposition” (

Gouvernement de la République Française 2021, p. 7).

Indeed, subject to a few differences, the adoption of restructuring plans continues to obey the same regime as the safeguard plans, so that the real divide in the construction of restructuring plans is due to the constitution or not of “classes of affected parties”, which has been uniformly extended to all procedures to avoid the coexistence of the two systems being a “source of confusion”.

Table 1 offers a comparative overview concerning the insolvency and reorganization regulation in the selected countries.

What is it that makes overseas restructuring law so attractive to legislators worldwide? If this thesis is put forward, it would be a case of “US American legal hegemony”, with the ulterior motive of facilitating trade with the USA—an economic power (

Walters 2017;

Oatley 2015). Even if economic motives may play a certain role, it would probably be too short-sighted to see this as the sole cause. Americans are widely recognized for their entrepreneurial spirit, and the high frequency of corporate restructuring cases has led to extensive scientific and legal–economic analysis (

Bebchuk 1988;

Markell 1991;

Epaulard and Zapha 2022). This, in turn, is expected to contribute to the development of “high-quality” laws (

Seymour and Schwarcz 2021;

Paulus 2021a). As seen above, a major insolvency-related response adopted in the selected jurisdictions was “the adoption of a moratorium against legal actions and/or termination of contracts outside of formal insolvency proceedings” (

Gurrea-Martínez 2020a, p. 5), also known as an automatic stay, seen as “the most important bankruptcy tool to preserve value” (

Gurrea-Martínez 2020b, p. 839) In this context, banks play a crucial role by receiving priority in subsequent insolvency proceedings if they continue supporting a company during the moratorium (

Gurrea-Martínez 2020b, p. 839). This approach generally aligns with the supportive saving policies adopted across all selected jurisdictions. However, the key differences in modern reorganization procedures lie in the mechanisms used to regulate holdouts. These include, on the one hand, the previously mentioned automatic stay, and on the other hand, the option of majority voting on a restructuring plan. With the lack of those tools, the procedure is a volunteer act, and creditors can participate or not, respectively, according to their will. In the case of English insolvency regulation, although there is no stay imposed, the majority voting is accepted. Meanwhile, in France, as already seen, the safeguard procedure imposes a stay “but does not allow all dissenting creditors to be bound by a plan agreed by a majority of creditors” (

Eidenmüller 2023a, p. 13).

3.1. Balancing Creditors’ and Debtors’ Interests: Creditor-Friendly or Debtor-Friendly?

An important aspect regarding bankruptcy and restructurings that makes the subject of the current analysis is the orientation that the selected jurisdictions have, being either creditor-friendly or debtor-friendly (

Porta et al. 1998), particularly since the changes in regulations influence entrepreneurs (debtors) and also the behavior of creditors, which is in our case the banks.

From an economic perspective, the real economy is highly impacted by insolvency law, particularly since insolvency regulations, due to their impact on debtors and creditors, affect their decisions, which in turn, impact employees, suppliers, tax authorities, and other diverse stakeholders. Thus, if an insolvency regime is unattractive for creditors and debtors, this will also negatively impact economic growth. Particularly because insolvency regulations catalyze economic growth, every country needs an efficient insolvency regime, on the one hand, to facilitate the reorganization of viable but financially distressed firms, and on the other hand, to be able to liquidate nonviable companies, balancing, and therefore, creditors’ and debtors’ rights.

Usually, when there is a shift towards a debtor-friendly regulation, a change occurs in the legal perspective, which could be found by creditors to be less-friendly. This shift in legislation can be viewed as increasing the risk for banks, since they could find it more difficult to recover debts in case of the debtor’s bankruptcy. For example, “the law changes often introduce measures that ensure that all new income obtained after bankruptcy goes directly to the bankrupt entrepreneur. While this may benefit debtors by providing them with a second chance, it also means that creditors may face increased risks and challenges in recovering their claims” (

Forier et al. 2023, p. 462). This is one major reason why a debtor-friendly insolvency regulation, which is by consequence less-friendly to creditors, can lead to the deficiency or even insufficiency of financial resources, “since creditors such as banks may become more cautious when extending credit to firms operating within a debtor-friendly insolvency environment” (

Forier et al. 2023, p. 462). Therefore, this increased caution on behalf of banks in extending credit to corporations in distress due to the banks’ possible struggle in the debt recovery process, is a consequence of pro-debtor laws. Studies confirmed that, in a pro-creditor approach, credits will be extended at favorable terms for debtors (

Routledge 2021;

Banasik et al. 2022), to the detriment of banks (creditors).

According to the literature, “an insolvency system is classified as a debtor-friendly jurisdiction if the insolvency legislation provides certain features that make a reorganization procedure attractive to debtors, such as the ability of the managers to keep running the firm during the procedure as well as the possibility of obtaining a moratorium or ‘stay’ that prevents creditors from initiating enforcement actions against the debtor” (

Gurrea-Martínez 2023, p. 3). Likewise, a jurisdiction can be seen as a pro-creditor insolvency system if an external administrator takes over management and the insolvency legislation lacks a comprehensive moratorium to shield the debtor from enforcement actions initiated by creditors (

Gurrea-Martínez 2023). Additionally, stipulations that can make a regulation attractive to either debtors or creditors, include, for example, (1) debtor-friendly provisions facilitating debtor-in-possession (“DIP”) financing, (2) the “cross-class cramdown”, referring to the ability of the debtor to impose a reorganization plan on dissenting classes of creditors, (3) the empowerment of creditors to appoint or remove an examiner or trustee (“insolvency practitioners”), and (4) the empowerment of creditors to decide important procedural aspects, such as the sale of assets, and others.

As far as the selected jurisdictions are concerned, several aspects need to be analyzed. First, we will focus on the US. Under the Small Business Reorganization Act (“SBRA”) adopted in 2019. The United States introduced subchapter V—11 U.S.C. § 1181 (Small Business Reorganization Act 2020), creating an opportunity to assist small business debtors to “streamline the bankruptcy process by which (they) reorganize and rehabilitate their financial affairs” (

U.S. Government House of Representatives 2019). This new regulation was adopted because the traditional Chapter 11 bankruptcy law was often inefficient for small business debtors, as it was primarily designed for bigger firm debtors. According to Michael Blackmon, “traditional Chapter 11 does not ‘work for small and medium-sized businesses because the (code) places unrealistic and artificial deadlines on small and medium-sized businesses’ which prevents them from restructuring” (

Blackmon 2019, p. 339).

Without claiming to be an exhaustive list, we will analyze the most notable changes the SBRA has introduced; these are provisions which clearly weaken the role of banks:

- (1)

The removal of tools considered onerous administrative expenditures (reduced expenses) and disclosure efforts (11 U.S.C. § 1181—this way, 11 U.S.C. § 1102 and 11 U.S.C. §1125 are no longer applicable; 11 U.S.C. § 1102—“[T]he United States trustee shall appoint a committee of creditors holding unsecured claims and may appoint additional committees of creditors or of equity security holders as the United States trustee deems appropriate.”; 11 U.S.C. § 1125—imposing the obligation to provide to the Court a written disclosure statement concerning its filed plan). Reorganizations according to Chapter 11 stipulated that, at the debtor’s expense, there will be made an appointment of a committee of unsecured creditors (banks), this being excluded in subchapter V (the provisions stipulated at 11 U.S.C. § 1181 of Chapter 11 of the US Code are no longer applicable in the SBRA, subchapter V). In this context, the SBRA weakens banks’ capacity to receive proper payment, negotiate, and enforce their rights (

Bradley 2020).

- (2)

The removal of the written disclosure statement, which, according to the Chapter 11 reorganizations, was initially provided to the debtor. Subchapter V eliminates this statement, implying an abolition of the “Absolute Priority Rule” (11 U.S.C. § 1181 (abolishes 11 U.S.C. § 1129(b)’s absolute priority rule), while bringing forth the plan or projected disposable income, also known as “Best Efforts Rule” (

Bonapfel 2019, p. 49). This rule is extensively more debtor-friendly, allowing “existing business owners to maintain their control and ownership of the business even if they confirm a plan that does not pay a dime to general unsecured creditors” (

Hall 2021, p. 595). At the same time, the debtor are able to “confirm a cramdown plan without the approval of any class of creditors” (

Norton and Bailey 2020, p. 385). Scholars confirm that this new provision offers a reduced influence of unsecured creditors in the process to facilitate a more balanced negotiation and achieve a consensual plan between the debtor and creditors (

LeBrun 2021).

As many scholars confirm, the SBRA represents a step towards salvaging small businesses (

Katz 2024), putting small businesses in a stronger position, protecting debtors (

Clevenger 2023), and therefore being debtor-friendly oriented, to the detriment of creditors (

LeBrun 2021;

Hall 2021).

In addition to this, the USA’s Bankruptcy Code Chapter 11 is also seen “as being very business-friendly, particularly in light of its ‘Automatic Stay’ provisions and clarity on the role of insolvency specialists in different types of insolvencies” (

Chauhan and Pandey 2024, p. 71).

While the absolute priority rule (APR) was originally envisaged in the draft European directive, the priority mechanism preferred by the PRD is now the more flexible alternative model of the relative priority rule (

de Weijs et al. 2019). In this case, a plan confirmation against the vote of a group of creditors even if a group of creditors that is subordinate to this group receives value under the plan (directive (EU) 2019/1023) at art. 11 para. 1 letter c., and this is the case of Germany, (SanIns-FoG, Section 28 of StaRUG), for instance. However, the member states can also provide for the APR following US Chapter 11 instead, or break through it in certain cases, as seen in SanIns-FoG, Section 28 of StaRUG.

As far as the UK is concerned, scholars consider that the bankruptcy regulations here are creditor-friendly (

Chauhan and Pandey 2024, p. 72), although the traditional creditor-friendly attitude has been toned down significantly by the changes introduced by “CIGA 2020”. Traditionally, the UK and Germany have had a rather creditor-in-control insolvency regime, due to the relationship-lending existing approach, with France being more oriented towards the debtor to protect employees. Meanwhile, the UK’s bankruptcy law “sets the interest of creditors first and is not particularly debtor-friendly, the existence of the scheme of arrangement, in particular, has encouraged early (and still solvent) restructurings in the mutual interest of creditors and debtors before the debtor was unable to pay its debt” (

Ehmke et al. 2019, p. 208). In the meantime, as already seen above, Germany clearly reformed its insolvency laws, making major improvements towards an environment that is more favorable to restructuring (

Ehmke et al. 2019).

All in all, it should be specified that this power game among creditors and debtors is not new, lately revealing “a considerable power shift in favor of the debtor. Limited liability, a rescue option rather than mandatory liquidation, and a short discharge period add up to fostering of entrepreneurship (indeed, the explicit purpose of the US and of the UK insolvency law)” (

Paulus 2022, p. 64). The US and UK’s experiences are not singular lately, as there are also other countries that adopted debtor-friendly modifications in their bankruptcy regimes. For instance, Germany “implemented reforms to its insolvency law in 2020, promoting early restructuring efforts and providing greater protection for debtors” (

Forier et al. 2023, p. 484). Germany is considered a “strong creditor protection regime”, just as UK. Still, many legislative changes occurred lately, the German insolvency law being reformed, and thus Germany became more restructuring-friendly even though is comes “from a very restrictive and restructuring-hostile approach, in which filing for insolvency almost always was synonymous with forced administration, the dissolution of the debtor’s company, the piece-meal liquidation of its assets, and with the debtor being branded as a failed entrepreneur” (

Ehmke et al. 2019, p. 194). The scheme in

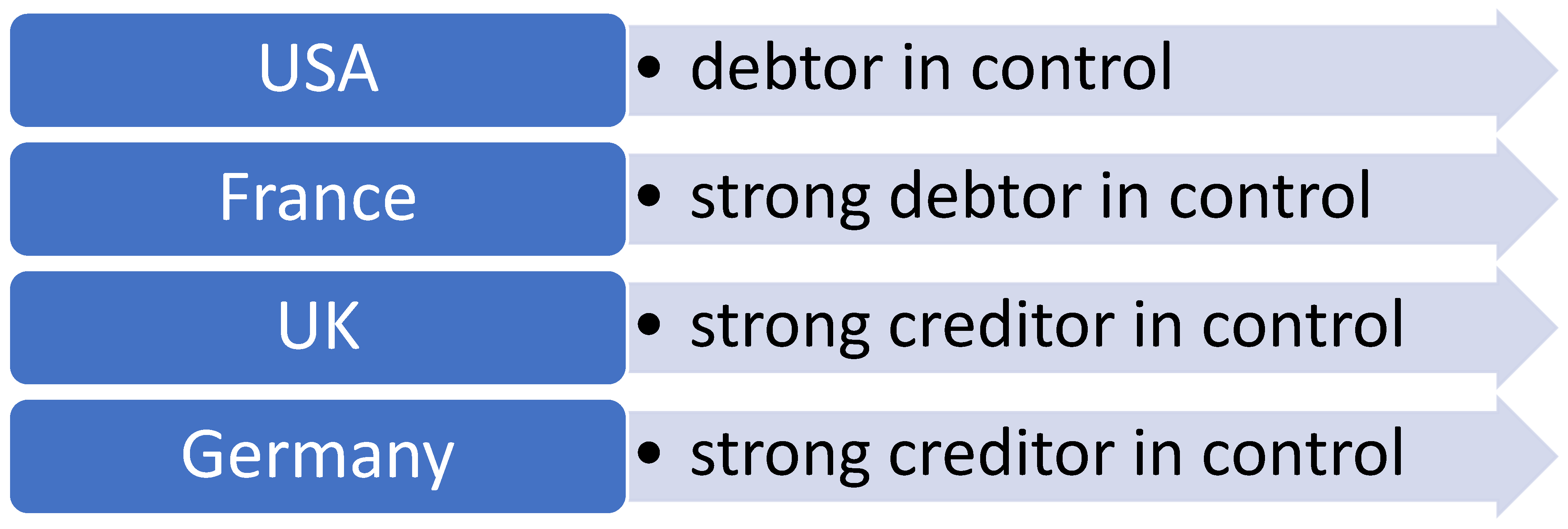

Figure 1 offers a general perspective on the orientation of the analyzed jurisdictions concerning their orientation (debtor versus creditor) in insolvency procedures:

Although the bankruptcy regulations of the four selected countries differ, there is a slight tendency lately towards the debtor-friendly regimes. From the analyzed group, the UK still adheres to the “creditor in control” model under the Insolvency Act 1986, just like Germany. Meanwhile, the US and France use the “debtor in possession” approach, with France being more strongly debtor-oriented than the US.

As already underlined before, the author considers that an ideal insolvency regulation should be pro-debtor and pro-creditor, and this can only be obtained by offering a very efficient reorganization of viable firms or an efficient allocation/utilization of the debtor’s assets, while also liquidating non-viable companies. Although this could be challenging, if one considers the examples of the United States and, more recently, the United Kingdom, it is not impossible.

3.2. Bankruptcy Procedures in the Selected Jurisdictions

3.2.1. The Initiation of Insolvency Proceedings

This section will focus on the opening of the insolvency proceedings, an important matter for all jurisdictions. If we take into consideration the international level, most jurisdictions make use of solvency and liquidity tests (

Ebeke et al. 2021;

Horobet et al. 2021), which usually confirm/infirm the ability of companies to pay their debts and by consequence whether insolvency proceedings should be opened.

Jurisdictions approach the initiation of insolvency proceedings differently. In Germany, requirements for opening insolvency proceedings are regulated in Section 16 of the insolvency code (Insolvenzordnung—InsO). However, a reason for insolvency is required. The German insolvency code recognizes three reasons for insolvency (

Dörr et al. 2021): insolvency following Section 17 of the InsO, over-indebtedness following Section 19 of the InsO, and impending insolvency under Section 18 of the InsO. The reasons for insolvency in Sections 17, 18, and 19 of the InsO are exhaustive.

Insolvency is the general and sole reason for insolvency for every applicant and every procedure and is legally defined in Section 17 paragraph 2 of the InsO. Accordingly, insolvency occurs when the debtor is unable to meet the payment obligations due. Insolvency is usually assumed if the debtor has stopped making payments. Insolvency must be distinguished from mere stagnation in payments.

Over-indebtedness stands alongside insolvency and is standardized in Section 19 paragraph 2 sentence 1 of the InsO. Over-indebtedness relevant to insolvency law arises only when it is likely that the company’s financial resources are insufficient to sustain business operations in the medium term. In contrast to insolvency, which refers to a debtor’s liquidity status at a specific point in time, over-indebtedness is linked to a longer period for assessing the debtor’s financial situation (

Pagoda and Thole 2021). Therefore, to protect creditors, a forecast of the company’s future liquidity must be created, a so-called continuation forecast. In addition to the continuation forecast, the probability of the company continuing as an ongoing concern must also be determined. This likelihood is met if the company can fulfill 50% of its payment obligations. Before the SanInsFoG came into force, the forecast period was often examined and determined by case law and practice on a case-by-case basis, meaning in some cases, it could extend to almost two years. However, the prevailing practice assumed a forecast period of 24 months.

The

imminent insolvency, regulated in Section 18 of the InsO, like the insolvency in Section 17 of the InsO, represents a general reason for insolvency for every procedure and every debtor. However, it has the special feature that it can only be used as a reason for insolvency concerning a self-application by the debtor himself. Thus, “as a ground for voluntary filing, the debtor can initiate the procedure in the case of pending illiquidity, which occurs when it becomes predominantly probable that the debtor will become illiquid. While both the debtor and the creditor are authorized to file for insolvency under mandatory insolvency reasons, only the debtor can initiate the procedure in the case of pending illiquidity. However, it is always the obligation of the debtor’s directors to initiate insolvency proceedings if mandatory insolvency reasons exist. A violation of this obligation constitutes a criminal offense, which, in the case of negligence, carries a prison sentence of up to one year or a fine” (

Pervan et al. 2023, p. 389). Therefore, in contrast to insolvency, there is no obligation to apply for impending insolvency; hence, there are no criminal consequences for failing to report it. Imminent insolvency is a right for the debtor who wishes to initiate insolvency proceedings at an early stage. Like over-indebtedness, impending insolvency is based on a forecast period and assesses whether the debtor will be able to meet their existing liabilities when they fall due. Before the SanInsFoG came into force, the forecast period for impending insolvency was not legally standardized. An unlimited time was assumed. In practice, due to practical manageability, a period of two years for assessing impending insolvency had developed. If it was highly likely that there was a gap in coverage about the debtor’s liabilities within two years, imminent insolvency was to be assumed. As a necessary prerequisite for taking advantage of the StaRUG measures, paragraph 1 of Section 29 of the German StaRUG requires the “sustainable elimination of an imminent insolvency” (

Paulus 2021b, p. 8) within the meaning of Section 18 paragraph 2 of the InsO (

Rauch 2022). The personal scope of application of the restructuring instruments of the preventive restructuring framework is therefore standardized by Section 29 paragraph 2 and Section 33 of StaRUG, in line with the provisions of the Preventive Restructuring Directive 2019/1023.

Making the opening of insolvency proceedings dependent on the existence of a reason for insolvency is due to the meaning and purpose of the insolvency proceedings themselves. If one considers that before insolvency occurs, the principle of “bellum omnium contra omnes” prevails in individual enforcement, i.e., all of the debtor’s creditors are satisfied by the priority principle, and this principle is replaced by the principle of equal treatment of creditors, “par condicio creditorum”, through the opening of insolvency proceedings, it becomes clear that the existence of a reason for insolvency marks a significant turn for the insolvency. Once there is a reason for insolvency and the opening of insolvency proceedings, the debtor is placed under judicial protection to achieve an orderly settlement and the equal satisfaction of their creditors or to facilitate the restructuring of their company. This protection requires certain conditions, because the debtor’s resources are no longer sufficient to fully satisfy all creditors. The insolvency procedure works with the logic of the collectivization of the realization of liability and justifies this transition through the existence of insolvency or excessive indebtedness to switch from the individual realization of liability to the collective realization of liability (

Köndgen 2021).

The Chapter 11 procedure can be initiated by the debtor (voluntary petition) according to 11 USC § 301, or by the creditors (involuntary petition) according to 11 USC § 303. There is no barrier to entry; the Chapter 11 procedure can be initiated even without a reason for insolvency. The most important consequence of the opening of the procedure is the immediate and automatic suspension of all court and enforcement proceedings against the debtor (automatic stay), according to 11 USC § 362. The debtor then has a period of 120 days to prepare the reorganization plan, after which creditors may also submit plan proposals according to 11 USC § 1121. Throughout the proceedings, the debtor retains control of the business.

The main features of Chapter 11 are debtor-in-possession and low-barrier-to-entry, as it is “designed to encourage early and easy access. It provides a statutory moratorium, plan voting, and confirmation mechanisms aimed at curbing opportunistic creditor behavior” (

Mevorach and Walters 2020, p. 865). It is inclined rather toward restructuring than asset sales (

Paterson 2016), while also including “safeguards designed to protect dissenting minorities in the plan voting and confirmation process, and to balance the interests of creditors who would prefer to crystallize their loss rather than wait for their money” (

Mevorach and Walters 2020, p. 865). Under Chapter 7, which regulates the assets liquidation, a trustee appointed by the Bankruptcy Court is responsible for gathering the debtor’s assets, selling them, and distributing the proceeds to creditors. In addition to this, for example, the regulatory strategy was, and still is, primarily based on rewarding shareholders/managers for early filing, which is also the purpose of Section 270b of the InsO from Germany, respectively, to offer the debtor who is willing to restructure and is already threatened with insolvency the opportunity to restructure at an early stage. This is also one of the aims of the Preventive Restructuring Directive 2019/1023, since it stipulates “a positive incentive for managers to use pre-insolvency proceedings with this characteristic to address anticipated difficulties at an early stage because they will not lose control by doing so” (

Mevorach and Walters 2020, p. 861).

This early-stage intervention addresses a debtor’s financial difficulties and also stands as the most attractive feature of the US Bankruptcy Code for debtors (both national and foreign) through Chapter 11. According to McCormack, “early-stage proceedings are designed to allow value to be preserved in an ailing business when there is still value that might be preserved. Technically there is no requirement that the company should be “insolvent” in the sense of inability to pay debts as they fall due and so-called strategic bankruptcies are a conspicuous part of the US scene. In other words, companies may have several reasons, other than insolvency strictly so-called, to invoke the protective cloak of Chapter 11” (

McCormack 2023, p. 196).

The UK approach and the French one are rather different. Both jurisdictions rely on liabilities (sticks) rather than on access to a debtor-in-possession restructuring proceeding (carrots) to secure an early filing. In England, Section 214 of the Insolvency Act 1986 stipulates that “the wrongful trading (…) applies whenever the company directors did not take appropriate actions and caused damage to the creditors by continuing to operate a company when they knew or ought to have known that the company had no reasonable prospects of avoiding insolvent liquidation or administration” (

Vaccari 2020, p. 129). Consequently, a director may be held to be liable (

Das 2023) for wrongful trading receiving stiff sanctions, and the legislation prioritizes the interests of creditors (

Chen 2023, p. 42). In the UK, the debtor is the only person who can initiate company voluntary arrangements, while restructuring plans and schemes of arrangement can be initiated by the debtor, by a creditor, or by any member. In the case of a company in administration or liquidation, any of the three processes of restructuring can be proposed by the liquidator or administrator.

In France, the “insolvency proceedings can be opened by a commercial court (tribunal de commerce), when the debtor’s activity is a commercial or craft activity (this includes commercial companies)” (

Mastrullo 2022, p. 8). In addition to this, the French liability regime art. L.651-2, sentence 1 of the Code de Commerce stipulates that, in the event of the judicial liquidation of a legal entity revealing an insufficient asset, “the court may, in the event of a management fault having contributed to this insufficient asset, decide that the amount of this insufficient asset will be borne, in whole or in part, by all the legal or de facto managers, or by some of them, having contributed to the management error” (

Lefebvre 2021, p. 96). This legal provision is similar to the English one.

In summary, the so-called ‘wrongful trading rule’ is approached differently in the analyzed jurisdictions. Instead of adopting the duty to file for insolvency, some member states (England and France, where criminal prosecution can be involved) are more creditor-friendly, providing for a duty to cease trading if creditors’ interests are at risk.

The concept of ‘liability for deepening insolvency’ is used in the US, as a variation on the liability for wrongful trading. In this approach, “continued corporate existence is often seen as a benefit because it fosters economic growth, maintains jobs, provides incentives for risky but possibly rewarding business undertakings, and generally benefits the community of interests that sustain a company. The theory of deepening insolvency, however, carves an exception to this general rule and suggests that where a company’s life is artificially prolonged, such existence cannot be deemed beneficial either to the company or to its creditors. On the contrary, the wrongful prolongation of a company’s existence beyond insolvency results in damage to creditors, usually caused by increased debt and the dissipation of assets” (

Bitė et al. 2022, p. 465).

Germany is a country using a hybrid, approach since it recognizes the principle of wrongful trading (

Prusko and Ehmke 2023), despite not directly naming it as in the UK; however, it also regulates a statutory duty to file for insolvency under several circumstances. However, the ‘wrongful trading’ is not stipulated in a concrete provision. The prohibition of wrongful trading in Germany is regulated by several regulations (Section 64, sentence 1, Limited Liability Company Act, and Section 823, para. 2, Civil Code, in conjunction with Section 15a, para. 4, Insolvency Act), which conduct “to the directors’ personal liability for any damages caused to the company and third-party creditors” (

Bitė et al. 2022, p. 466). In the self-administration procedure according to Section 270b of the InsO, the debtor is generally responsible for the administration and disposal of the insolvency assets. Nevertheless, Section 280 of the InsO provides an important exception to this for special tasks, where it is unlikely that the debtor can perform them properly due to an obvious conflict of interests and a lack of legal knowledge. These special tasks are generally assigned to the administrator and, in addition to the right under Section 92 of InsO, this includes asserting total damages against the insolvency administrator, i.e., against the debtor in self-administration, and the enforcement of claims for personal liability of shareholders.

3.2.2. Insolvency Governance Proceedings

Conflicts arise from incompatibilities in thinking, feeling, perception, or from incompatibilities in interests, intentions, and goals between at least two parties, where at least one party perceives them as detrimental. When typifying conflicts in the context of insolvency crises, those conflicts that were or still are the triggers of the corporate crisis (

McCormack 2023;

Sgrò et al. 2021) at an earlier crisis stage must also be taken into account. Another important distinction for the typification of conflicts in corporate crises must be made between the terms of the conflict party and their role in the conflict. The same conflicting party can simultaneously hold several roles in which it is involved in one or even several conflicts (

Benedetti et al. 2021). In their role as a creditor, a company’s supplier may have an interest in enforcing their claim, but at the same time, in their role as a permanent contractual partner, they can have an interest in future sales and thus in maintaining the company. The same applies to the company that is in jeopardy and is capable of restructuring, called the “debtor”, even if its role is in no way limited to that of one debtor within the meaning of the law of obligations. Insolvency and restructuring usually exacerbate conflicts of interest (

Kokorin 2020). This adds new parties to the conflict in addition to debtors (shareholders/managers) and creditors, such as insolvency courts, insolvency practitioners, and state/government institutions, all of them becoming relevant actors in the insolvency conflict, performing specific roles. What counts is who leads the insolvency procedures in the analyzed jurisdictions, i.e., who holds the control. As already seen in

Section 3.2, the orientation of the analyzed jurisdictions (debtor versus creditor) in insolvency procedures is a strong creditor in control in the UK and Germany, with the US to a certain extent in the middle with the debtor in control, while France has a strong debtor-in-control approach.

Indeed, if we consider the insolvency procedure in the UK, particularly if we refer to Part I “Company Voluntary Arrangements” (CVA) (restructuring) and the “Scheme of Arrangement (SoA)”, neither of them stipulates an insolvency administrator/receiver, which offers creditors bigger control.

The StaRUG in Germany refers to the restructuring officer in Part 2, Chapter 3, providing for the appointment of a restructuring representative by the restructuring court in Sections 73–83 of the StaRUG. Just like a referral to the restructuring court, the appointment of a restructuring officer (following Sections 73–83 of StaRUG) by the restructuring court is only provided for in certain cases. The restructuring plan process and the instruments of the stabilization and restructuring framework are designed as an essentially out-of-court restructuring process. Accordingly, the law dispenses with providing the debtor (

Gallagher et al. 2020) with a court-appointed restructuring agent in every case (justification for the StaRUG, General part, 19/24181, p. 93). A distinction is made between the appointment ex officio and appointment upon application (

Shishmareva 2021). From a conflict theory perspective, it is uncertain what role the restructuring officer plays, particularly in terms of their function in conflict management and the tools they employ. This also determines what requirements must be placed on the qualifications of the restructuring officer. A distinction must be made between the necessary restructuring officer (appointed ex officio) and the optional restructuring officer. In the latter case, the optional restructuring officer supports the debtor and the creditors in developing and negotiating the restructuring plan (§ 79 StaRUG). The restructuring officer appointed ex officio, however, is tasked with extensive auditing and monitoring duties to safeguard the interests of the creditors (Section 76 StaRUG) and the secured creditors. The monitoring function, on the other hand, seems to be aimed more at ensuring the integrity and acceptance of the restructuring project as a whole. In both functions, the restructuring officer works in the interests of the creditors. Since the restructuring officer oversees the negotiating process and agrees on a restructuring plan, their activity is a tool for dealing with the same conflicts as the restructuring plan. First and foremost, it serves to attenuate conflicts. Concerning their appointment and supervision by the court and their powers, it can be said that the necessary restructuring officer acts like a kind of “extended arm” to the restructuring court in their supervisory function. In doing so, it ensures the integrity and efficiency of conflict processing, but above all the interests of the creditors are taken into account.

The UK and German legal systems approach differently the matter of restructuring officers. In Germany, the moratorium is to be combined only under certain conditions with the appointment of an official restructuring officer. As already seen above, a Restructuring Practitioner (pursuant to sec. 73 StaRUG) “is only to be appointed by the court ex officio if the moratorium affects the rights of consumers or medium-sized, small, or micro-enterprises, if it is essentially directed against all creditors, or if it is foreseeable that the restructuring objective can only be achieved by making use of the rule on obstruction ban (cross-class cram-down)” (

Bork 2021, p. 7). On the contrary, in England, the involvement of a Restructuring Practitioner is mandatory since “the debtor must, in any case, bring along a monitor who must (among other things) also comment on the conditions of the moratorium sought” (sec. A6 (1) IA 1986).

Just as the restructuring officer, the insolvency courts both in the UK (

Sachdev 2019) and in Germany act rather as legislative arbitrators (

van den Ven 2023), making sure that procedures and rights are respected. In this context, the new restructuring tools in the UK, and particularly SoA, stipulate that “a scheme is an arrangement is a court-approved mechanism that enables a company to enter into an arrangement with its creditors and/or shareholders involving inter alia a restructuring of its debts. Subject to the receipt of certain voting requirements the scheme can be sanctioned by the court and consequently binding on the involved creditors and/or shareholders” (

Karapetian 2022, p. 202). In addition to this, the Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act 2020 introduces the “‘restructuring plan’ and implements a cross-class cramdown by means of which the court has the discretion to impose the plan on dissenting classes of creditors or shareholders subject to certain safeguards” (

Karapetian 2022, p. 202). Therefore, the court seems to mediate in the UK, particularly if we also consider that “there is no insolvency test for court confirmation of the plan” (

Karapetian 2022, p. 202).

This is however not the case in the US, where usually, the debtor is more favored, although the last modification of the regulations weakened this debtor-friendly approach to a certain extent. Indeed, the recent adding of the “Subchapter V” proceeding (

U.S. Government House of Representatives 2019) requires less judicial intervention, but at the same time, commentators argue that “strict rules that reduce judicial involvement and discretion will transfer power and control from the court to one of the parties. This changes the bargaining dynamics between stakeholders, which can change the ultimate pay-outs that those stakeholders receive from the insolvency proceeding” (

Casey and Macey 2024, p. 5). Indeed, in the US, the interaction between insolvency and corporate governance law defines the one in control once the procedure is opened. Thus, “the law might call for the appointment of a trustee or administrator, or it might implement a debtor- or creditor-in-possession system” (

Casey and Macey 2024, p. 9).

In France, the most important governance role is held by bankruptcy courts. The French court “can decide on the closure, sale or restructuring of distressed business-regardless of the business’ economic viability” (

Eidenmüller 2023a, p. 34). In addition to this, the French court can also appoint an

administrateur judiciaire in certain conditions. Their main responsibility lies in both supervision and assistance of the debtor and their management team, this responsibility being often stronger in the case of the

redressement judiciaire than in

sauvegarde. In the first case, apart from supervision and assistance, the

administrateur also has the role of representing the debtor. If a plan is adopted, he can be appointed as a ‘

commissaire à l’exécution du plan’ and will ensure the appropriate and legitimate plan execution (

Gouvernement de la République Française 1807). In both cases,

redressement judiciaire and/or

sauvegarde “a

juge-commissaire is also designated, their mission is to ensure that the procedure is carried out rapidly and that the interests involved are protected” (

Mastrullo 2022, p. 9).

To sum up, the insolvency procedure in the UK does not stipulate an insolvency administrator/receiver. On the contrary, all other selected jurisdictions regulate the appointment of an administrator/restructuring officer/trustee under various names, most of the time holding the power of an arbitrator. In Germany, however, the interests of the creditors are prioritized above all else. In addition to this, the insolvency courts both in the UK and in Germany act rather as legislative mediators, making sure that procedures and rules are respected. Meanwhile, in France, the courts play the most significant role, once again demonstrating the strong debtor-in-control approach. In the US, there are more possibilities, with creditors being able to appoint a trustee or administrator or implement a debtor- or creditor-in-possession approach.

3.2.3. Priority of Claims

The ranking system of claims holds an important position in the design of corporate insolvency laws, with a major focus on secured creditors, which explains the challenging efforts of harmonization in this area. For a clearer viewpoint, the main approaches in the selected jurisdictions will be scrutinized, concentrating on secured creditors.

Germany has the simplest ranking system, the first ones being the secured creditors, followed by administrative expenses and unsecured creditors. Secured creditors in Germany “hold an intermediate position, as a collective procedure is mandated, accompanied by a three-month automatic stay on creditors’ claims” (

Biresaw et al. 2024, p. 50). The absolute priority rule has been incorporated in § 27 of StaRUG. This implements art. 11 paragraph 2 of the PRD, according to which the claims of affected creditors in a negative voting class are satisfied in full and in the same or equivalent manner if a subordinated class receives a payment or retains an interest under the restructuring plan. Section 27 paragraph 1 of the StaRUG standardizes the regulations for the affected creditors, while Section 27 paragraph 2 of the StaRUG applies to persons involved. Section 28 of the StaRUG provides for exceptions to the absolute priority rule, incorporating various legal considerations. Cramdown is always about the conditions under which the will of the majority of those affected by the plan should prevail against an opposing minority. This is fundamentally about the comparison between those involved in the plan (are equals treated equally or is there justification for unequal treatment?) and a comparison with the results of insolvency proceedings (would the dissident parties affected by the plan achieve a better result in the insolvency proceedings?). Whether unequal treatment is appropriate in this context will also depend, among other things, on whether it adequately promotes the restructuring goal and thereby improves the creditors’ prospects of satisfaction. The ultimate limitation on unequal treatment under German law is the prohibition against worsening a party’s position compared to the next best alternative scenario. As a result, disadvantaged creditors cannot be given a better position in insolvency plan proceedings than in restructuring proceedings.

The US approach to restructuring is market-driven and creditor-driven. The American system has developed independently in out-of-court restructuring. Although the equity receivership procedure was formally a type of transferring restructuring within a legal procedure, from a substantive point of view the restructuring plan functions as a contract that was prepared and agreed upon out of court and whose fairness was only loosely secured in court according to the priority rules (

Roe 2017). The differentiation between various types of unsecured creditors is also reflected in the US system. Secured creditors have the highest priority, followed by unsecured creditors, and the other creditors are paid before equity shareholders.

The US common law and insolvency laws recognize distinct security positions, and it goes without saying that higher-ranked debt is paid off before less-secured debt. The situation is the same in the UK (

Chauhan and Pandey 2024, p. 77). In the UK, according to CVA, “a company’s creditors fall into a range of categories including financial bodies (banks and other financial institutions, of which the majority are usually secured creditors); trade and expense creditors that vary depending on the type and location of the business; connected party creditors (associated businesses and employees); and finally the range of taxes due (including PAYE, National Insurance, VAT, corporation tax, other customs duties, and other local authority taxes)” (

Morgan 2022, p. 137). Thus, the UK offers robust protection to secured creditors. Also, “upon default, secured creditors have significant control over the company, and there is no automatic stay against creditors’ claims. Unsecured creditors have limited control rights and are excluded from participating in selling the company’s assets. They do not receive any payouts unless the claims of secured creditors have been entirely settled” (

Davydenko and Franks 2008).

In France, the rights of unsecured creditors prevail (