Establishing Boundaries to Combat Tax Crimes in Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. A Brief Introduction to the Legal System in Indonesia

3.1. Legal System (LS)

3.2. Administrative Penal Law in Indonesia

3.3. Preliminary Investigation and Tax Investigation

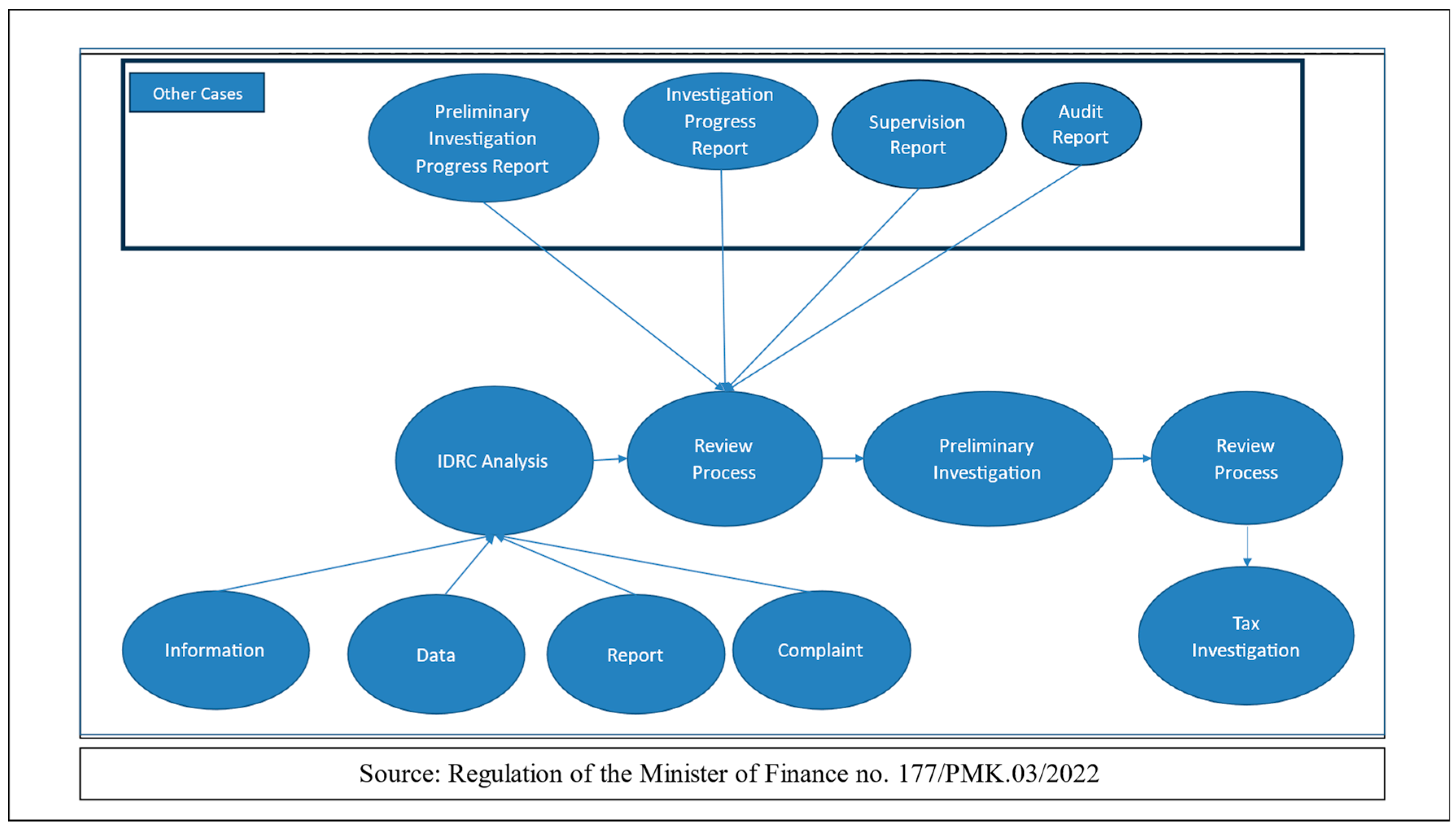

3.4. Proposing a Tax Investigation Case in Indonesia

4. Findings

5. Discussion

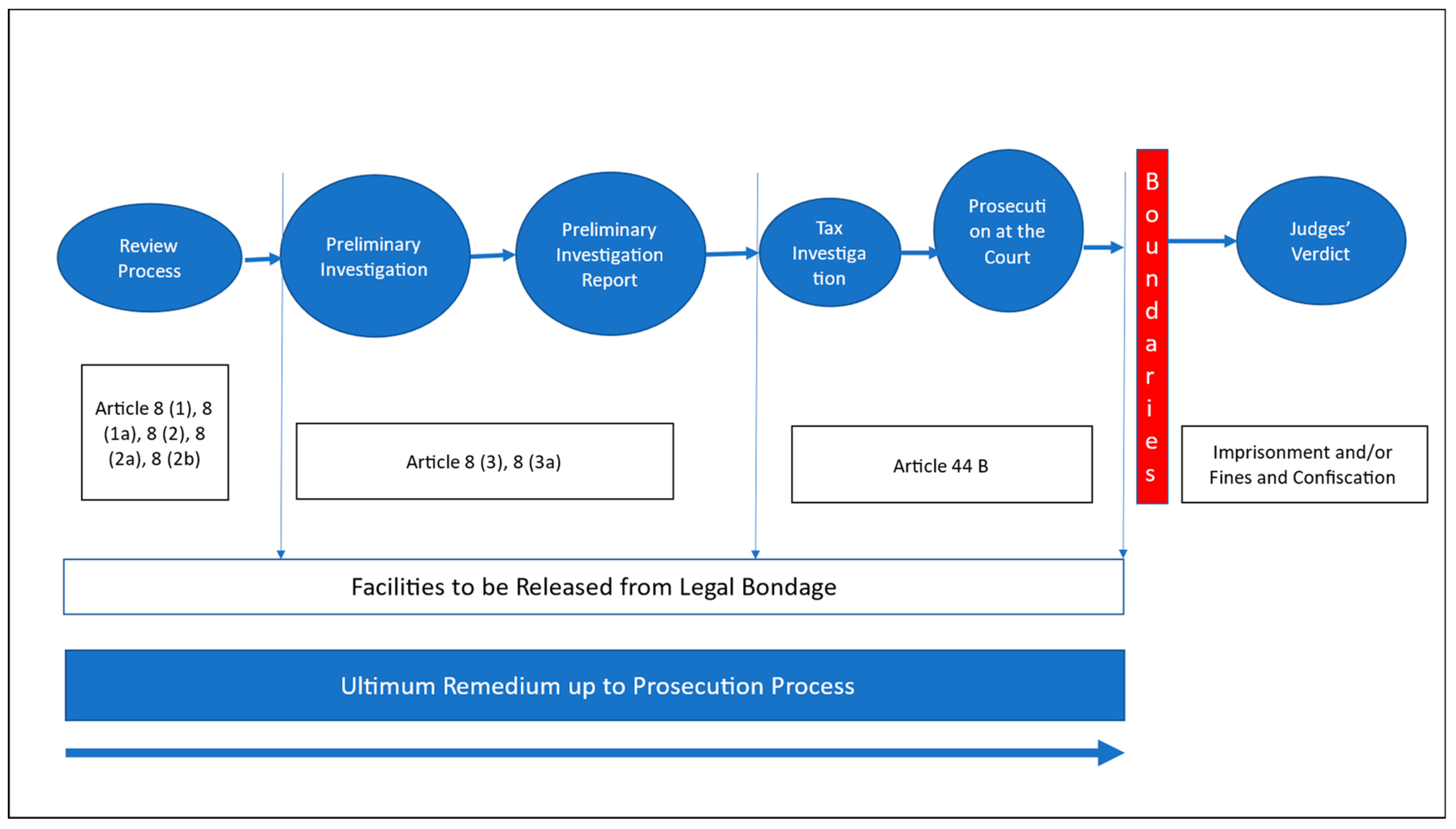

5.1. Current Policies and Facilities of Handling Tax Crimes in Indonesia

5.1.1. Criminal Provisions in the GPTP Act

5.1.2. Facilities for Tax Offenders

5.1.3. Evaluation of Current Policies

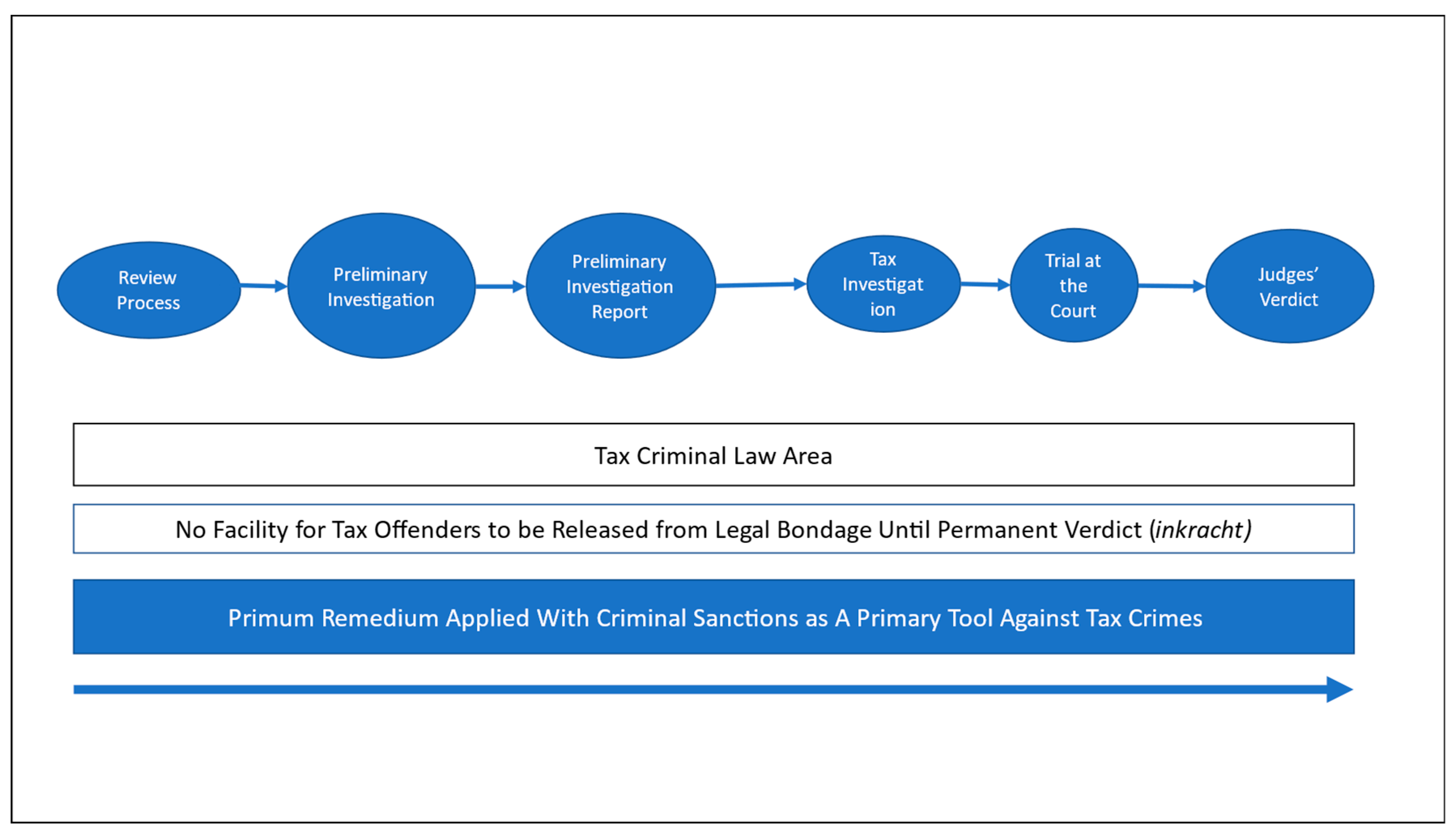

5.2. Implementing Primum Remedium Policies in Tax Crime Cases as an Alternative

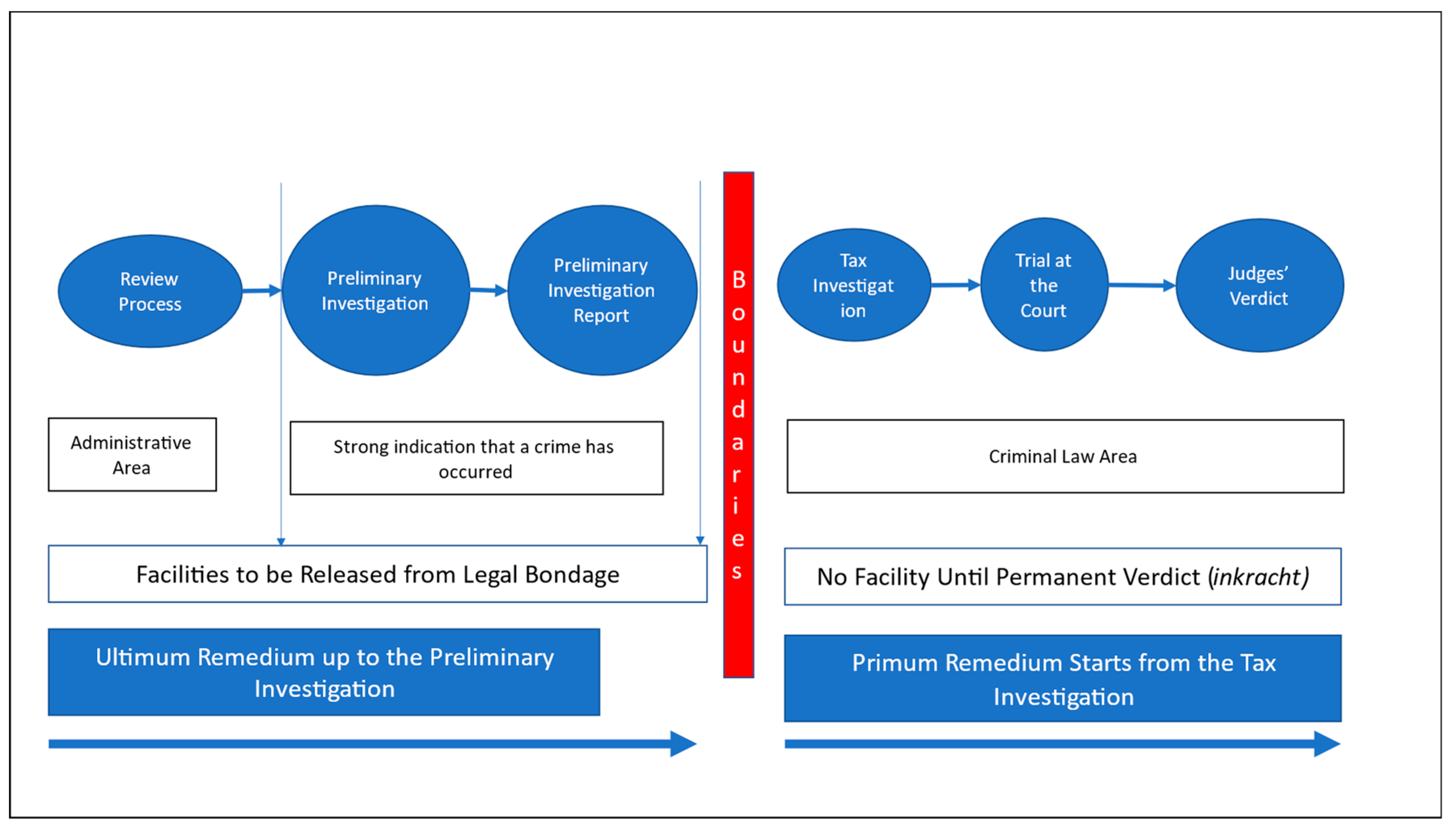

5.3. Proposed Policies

- 100% of the tax owed to taxpayers who are indicated to have committed tax crimes as a result of negligence, as regulated in Article 38 of the GPTP Act;

- 200% of the tax owed to taxpayers who are indicated to have intentionally committed tax crimes, as regulated in Articles 39, 39A, and 43 (1) of the GPTP Act, sanctions for criminal offenders who intentionally committed crimes must be aggravated as they have bad intentions (mens rea) to evade taxes in Indonesia.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Article | Paragraph | Contents |

|---|---|---|

| 38 | Any person who, through negligence:

| |

| 39 | (1) | Any person who intentionally:

|

| (2) | The penalty, as referred to in paragraph (1), is increased by one time to two times the criminal sanction if a person commits another crime in the field of taxation before one year has passed, starting from the completion of serving the prison sentence imposed. | |

| (3) | Any person who attempts to commit a criminal act misuses or uses without the right of a taxpayer identification number or confirmation of taxable enterprise as intended in paragraph (1b), or submits a tax return and or information whose contents are incorrect or incomplete, as intended in paragraph (1d), to submit a request for restitution or implement tax compensation or tax credit, shall be punished with imprisonment for a minimum of six months and a maximum of two years and a fine of at least two times the amount of restitution requested and or compensation or credit made and a maximum of four times the amount of restitution requested and or compensation or credit made. | |

| 39A | Any person who intentionally:

| |

| 41 | (1) | An official who, due to negligence, does not fulfill the obligation to keep matters confidential as intended in Article 34 shall be punished with imprisonment for a maximum of one year and a fine of a maximum of IDR 25,000,000.00 (twenty-five million rupiahs). |

| (2) | An official who deliberately does not fulfill his/her obligations or a person who causes the official’s obligations to not be fulfilled as intended in Article 34 shall be punished with a maximum imprisonment of two years and a maximum fine of IDR 50,000,000.00 (fifty million rupiahs). | |

| (3) | Prosecution of criminal acts as intended in paragraphs (1) and (2) is only performed on complaints from people whose confidentiality has been violated. | |

| 41A | Every person who is obliged to provide information or evidence requested as intended in Article 35 but who deliberately does not provide information or evidence or provides information or evidence that is not true shall be punished with imprisonment for a maximum of 1 (one) year and a fine of a maximum of IDR 25,000,000.00 (twenty-five million rupiahs). | |

| 41B | Any person who intentionally obstructs or complicates the investigation of criminal acts in the field of taxation shall be punished with imprisonment for a maximum of 3 (three) years and a fine of a maximum of IDR 75,000,000.00 (seventy-five million rupiahs). | |

| 41C | (1) | Every person who deliberately does not fulfill the obligations as intended in Article 35A paragraph (1) shall be punished with imprisonment for a maximum of 1 (one) year or a fine of a maximum of IDR 1,000,000,000.00 (one billion rupiahs). |

| (2) | Every person who intentionally causes the obligations of officials and other parties to fail as intended in Article 35A paragraph (1) shall be punished with imprisonment for a maximum of 10 (ten) months or a fine of a maximum of IDR 800,000,000.00 (eight hundred million rupiahs). | |

| (3) | Every person who deliberately does not provide data and information requested by the Director General of Taxes as intended in Article 35A paragraph (2) shall be punished with imprisonment for a maximum of ten months or a fine of a maximum of IDR 800,000,000.00 (eight hundred million rupiahs). | |

| (4) | Any person who deliberately misuses tax data and information to effect losses to the state shall be punished with imprisonment for a maximum of one year or a fine of a maximum of IDR 500,000,000.00 (five hundred million rupiahs). | |

| 43 | (1) | The provisions as intended in Article 39 and Article 39A also apply to representatives, proxies, taxpayer employees, or other parties who order, participate in, encourage, or assist in committing criminal acts in the field of taxation. |

| (2) | The provisions, as intended in Article 41A and Article 41B, also apply to those who order, encourage, or assist in committing criminal acts in the field of taxation. |

| Article | Paragraph | Contents |

| Administrative Sanctions | ||

| 8 | (1) | Taxpayers, of their accord, can correct the tax return that has been submitted by proffering a written statement on the condition that the Director General of Taxes has not conducted an audit action. |

| (1a) | If the correction to the notification letter as intended in paragraph (1) states a loss or overpayment, the correction to the tax return must be submitted no later than two years before the expiry of the determination. | |

| (2) | If a taxpayer corrects the annual tax return himself/herself, which results in larger tax debt, he/she will be subject to administrative sanctions in the form of interest at the monthly interest rate determined by the Minister of Finance for the amount of underpaid tax, calculated from the time the submission of the tax return ends until the date of payment, and is subject to a maximum of 24 months and part of the month is calculated as a whole one month. | |

| (2a) | If a taxpayer corrects the periodic tax return himself/herself, which results in relatively larger tax debt, he/she is subject to administrative sanctions in the form of interest at the monthly interest rate determined by the Minister of Finance for the amount of the underpaid tax, calculated from the due date of payment until the payment date, and it is subject to a maximum of 24 months, and part of the month is calculated as a whole one month. | |

| (2b) | The monthly interest rate determined by the Minister of Finance as intended in paragraph (2) and paragraph (2a) is calculated based on the reference interest rate plus 5% and divided by 12, which applies to the start date of calculating sanctions. | |

| Preliminary Investigation | ||

| 8 | (3) | Even though a preliminary investigation has been conducted, the taxpayer, of his/her accord, can disclose, through a written statement, the untruthfulness of his/her actions, namely as follows:

|

| (3a) | Disclosure of incorrect actions as intended in paragraph (3) shall be accompanied by repayment of the underpayment of the amount of tax actually owed, along with administrative sanctions in the form of a fine of 100% of the amount of underpaid tax. | |

| Investigation, Prosecution, and Trial | ||

| 44B | (1) | For the purposes of state revenue, at the request of the Minister of Finance, the Attorney General may stop investigations into criminal acts in the field of taxation within six months from the date of the request letter. |

| (2) | Termination of investigations into criminal acts in the field of taxation, as referred to in paragraph (1), is only conducted after the taxpayer or suspect has paid:

| |

| (2a) | If a criminal case has been transferred to court, the defendant can still pay:

| |

| (2b) | Payment as intended in paragraph (2a) is considered for prosecution without being sentenced to imprisonment. | |

| (2c) | In the case of payments made by taxpayers, suspects, or defendants at the investigation stage until trial fulfill the amount as intended in paragraph (2), the payment can be calculated as payment of the criminal fine imposed on the defendant. | |

References

- Abu Hassan, Norul Syuhada, Mohd Rizal Palil, Rosiati Ramli, and Ruhanita Maelah. 2021. Does Compliance Strategy Increase Compliance? Evidence from Malaysia. Asian Journal of Accounting and Governance 15: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adji, Indriyanto Seno. 2014. Principles of Criminal Law & Criminology and its Development Today/Asas-Asas Hukum Pidana & Kriminologi Serta Perkembangannya Dewasa Ini. Academic Paper. Yogyakarta. [Google Scholar]

- Aktaş Güzel, Sonnur, Gökhan Özer, and Murat Özcan. 2019. The Effect of the Variables of Tax Justice Perception and Trust in Government on Tax Compliance: The Case of Turkey. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics 78: 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allingham, Michael G., and Agnar Sandmo. 1972. Income Tax Evasion: A Theoretical Analysis. Journal of Public Economics 1: 323–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, James. 1991. A Perspective on the Experimental Analysis of Taxpayer Reporting. The Accounting Review 66: 577–93. [Google Scholar]

- Alm, James. 2012. Measuring, Explaining, and Controlling Tax Evasion: Lessons from Theory, Experiments, and Field Studies. International Tax and Public Finance 19: 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apeldoorn, Lambertus Johannes van. 1959. Introduction to the Study of Dutch Law/Inleiding Tot de Studie van Het Nederlandse Recht (Translated). Jakarta: Noordh FF-Kolfs NV. [Google Scholar]

- Barkan, Steven M., Barbara Bintliff, and Mary Whisner. 2015. Fundamentals of Legal Research, 10th ed. Goleta: Foundation Press. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2591470 (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- Black’s Law Dictionary. 1990, Black’s Law Dictionary, 6th ed. Minnesota: West Publishing Company.

- Chelvaturai, S. I. 1985. Tax Avoidance, Tax Evasion, and The Underground Economy. London: The Cata Experience. [Google Scholar]

- Childers, Thomas. 1989. Evaluative Research in the Library and Information Field. Library Trends 38: 250–67. [Google Scholar]

- Claus, Iris, Jorge Martinez-Vazquez, and Violeta Vulovic. 2014. Government Fiscal Policies and Redistribution in Asian Countries. In Inequality in Asia and the Pacific: Trends, Drivers, and Policy Implications. Edited by Ravi Kanbur, Changyong Rhee and Juzhong Zhuang. London: Routledge, pp. 197–225. [Google Scholar]

- Constitutional Court Decision No. 83/PUU-XXI/2023. 2024. Available online: https://mkri.id/public/content/persidangan/putusan/putusan_mkri_9609_1707811688.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Crivelli, Ernesto, Ruud De Mooij, and Michael Keen. 2016. Base Erosion, Profit Shifting and Developing Countries. FinanzArchiv 72: 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Feria, Rita. 2020. Tax Fraud and Selective Law Enforcement. Journal of Law and Society 47: 240–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feld, Lars Peter, and Bruno S. Frey. 2012. Deterrence and Tax Morale: How Tax Administrations and Taxpayers Interact. Available online: https://web-archive.oecd.org/2012-06-15/160289-2789923.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Galbiati, Roberto, and Giulio Zanella. 2012. The Tax Evasion Social Multiplier: Evidence from Italy. Journal of Public Economics 96: 485–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilliot, Harold J., and Frank A. Schubert. 1989. Introduction to Law & the Legal System, 4th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. [Google Scholar]

- Hartner, Martina, Silvia Rechberger, Erich Kirchler, and Alfred Schabmann. 2008. Procedural Fairness and Tax Compliance. Economic Analysis and Policy 38: 137–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, Richard. 2014. CSOs-and-Corruption-in-Indonesia. Available online: http://www.richardholloway.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/CSOs-and-Corruption-in-Indonesia.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Ibrahim, Johnny. 2005. Normative Legal Research Theory and Methods/Teori dan Metode Penelitian Hukum Normatif. Malang: Bayumedia Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Indonesian Constitution of 1945 as Lastly Amended in 2002; n.d. Available online: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/101646/uud-no-- (accessed on 4 December 2023).

- Indonesian Criminal Act 2023; n.d. Available online: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/234935/uu-no-1-tahun-2023 (accessed on 4 December 2023).

- Indonesian Criminal Procedural Act 1981; n.d. Available online: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/47041/uu-no-8-tahun-1981 (accessed on 4 December 2023).

- Indonesian General Provisions and Tax Procedures Act 1983 as Lastly Amended in 2023; n.d. Available online: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/246523/uu-no-6-tahun-2023 (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Indonesian Harmonization of Tax Regulation Act 2021; n.d. Available online: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/185162/uu-no-7-tahun-2021 (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- James, Philip S. 1976. Introduction to English Law, 9th ed. London: Butterworths. [Google Scholar]

- Kansil, C. S. T. 1989. Introduction to Law and Indonesian Legal System/Pengantar Ilmu Hukum dan Tata Hukum Indonesia. Jakarta: Balai Pustaka. [Google Scholar]

- Kartanto, Lucky, Prasetijo Rijadi, and Sri Priyati. 2020. Quo Vadis Ultimum Remedium in Tax Criminal Crimes In Indonesia. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications (IJSRP) 10: p9902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim, Azhar. 2013. Bureaucratic Reform and Dynamic Governance for Combating Corruption: The Challenge for Indonesia. Bisnis & Birokrasi Journal 20: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaulu, Byrne. 2022. Determinants of Tax Evasion Intention Using the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Mediation Role of Taxpayer Egoism. Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences 15: 63–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemenkeu. 2023. Informasi-APBN-TA-2023. Available online: https://media.kemenkeu.go.id/getmedia/6439fa59-b28e-412d-adf5-e02fdd9e7f68/Informasi-APBN-TA-2023.pdf?ext=.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2023).

- Kilonzo, Susan Mbula, and Ayobami Ojebode. 2023. Research Methods for Public Policy. In Public Policy and Research in Africa. Edited by Emmanuel Remi Aiyede and Beatrice Muganda. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klemm, Alexander, and Stefan Van Parys. 2012. Empirical Evidence on the Effects of Tax Incentives. International Tax and Public Finance 19: 393–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laoly, Yasonna. 2020. perlu-penegasan-norma-i-ultimum-remedium-i-soal-pengenaan-sanksi-di-aturan-turunan-uu-cipta-kerja. Available online: https://www.hukumonline.com/berita/a/perlu-penegasan-norma-i-ultimum-remedium-i-soal-pengenaan-sanksi-di-aturan-turunan-uu-cipta-kerja-lt5fe9c7c822f4e?utm_source=website&utm_medium=internal_link_klinik&utm_campaign=ultimum_remedium_ciptaker (accessed on 17 December 2023).

- Lubis, Todung Mulya, and Alexander Lay. 2009. Death Penalty Controversy: Dissenting Opinion of Constitutional Judges/Kontroversi Hukuman Mati: Perbedaan Pendapat Hakim Konstitusi. Jakarta: Sinar Grafika. [Google Scholar]

- Majchrzak, Ann, and M. Lynne Markus. 2014. Methods for Policy Research: Taking Socially Responsible Action. London: SAGE Publications, Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manan, Bagir. 1999. Research in the field of Law/Penelitian di Bidang Hukum. In Jurnal Hukum. Bandung: Pusat Penelitian Perkembangan Hukum, Lembaga Penelitian Universitas Padjadjaran. [Google Scholar]

- Marbun, Rocky. 2016. Rekonstruksi Sistem Pemidanaan Dalam Undang-Undang Perpajakan Berdasarkan Konsep Ultimum Remidium. Jurnal Konstitusi 11: 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroni. 2015. Introduction to Administrative Penal Law/Pengantar Hukum Pidana Administrasi. Lampung: CV. Anugrah Utama Raharja (AURA). [Google Scholar]

- Marzuki, Peter Mahmud. 2005. Legal Reseach/Penelitian Hukum. Jakarta: Kencana. [Google Scholar]

- Mertokusumo, Sudikno. 1986. Introduction to Law/Mengenal Hukum. Yogyakarta: Liberty. [Google Scholar]

- Mertokusumo, Sudikno. 2006. The Discovery of Law: An Introduction, 4th Edition/Penemuan Hukum: Suatu Pengantar, 4th ed. Yogyakarta: Liberty. [Google Scholar]

- Muladi. 1995. Capita Selecta Criminal on Justice System/Kapita Selekta Sistem Peradilan Pidana. Semarang: Badan Penerbit Universitas Diponegoro. [Google Scholar]

- Oberholzer, Ruanda, and E. M. Stack. 2014. Possible Reasons for Tax Resistance in South Africa: A Customised Scale to Measure and Compare Perceptions with Previous Research. Public Relations Review 40: 251–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2017. Fighting Tax Crime—The Ten Global Principles, First Edition: The Ten Global Principles. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2021a. Fighting Tax Crime—The Ten Global Principles (Second Edition). Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2021b. Fighting Tax Crime—The Ten Global Principles (Second Edition) Country Chapters. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Ovcharova, Elena, Kirill Tasalov, and Dina Osina. 2019. Tax Compliance in the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and the United States of America: Forcing and Encouraging Lawful Conduct of Taxpayers. Russian Law Journal 7: 4–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, Ronald R. 2006. Evaluation Research: An Overview. Library Trends 55: 102–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodjodikoro, Wirjono. 2003. Principles of Criminal Law in Indonesia/Asas-Asas Hukum Pidana Di Indonesia. Bandung: Refika Aditama. [Google Scholar]

- Radbruch, Gustav. 2006. Statutory Lawlessness and Supra-Statutory Law (1946). Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 26: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmawati, Nur Ainiyah. 2013. Hukum Pidana Indonesia: Ultimum Remedium Atau Primum Remedium. Recidive 2: 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation of the Minister of Finance No. 177/PMK.03/2022 Concerning Procedures for Initial Evidence Examination; n.d. Available online: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/232898/pmk-no-177pmk032022 (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Reuters. 2023. Indonesia-Offers-Golden-Visa-Entice-Foreign-Investors. September 3. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/indonesia-offers-golden-visa-entice-foreign-investors-2023-09-03/ (accessed on 28 December 2023).

- Robertson-Snape, Fiona. 1999. Corruption, Collusion and Nepotism in Indonesia. Third World Quarterly 20: 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikka, Prem. 2017. Accounting and Taxation: Conjoined Twins or Separate Siblings? Accounting Forum 41: 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, Elsa Priskila, Diana Pangemanan R., and Daniel F. Aling. 2021. Primum Remedium in Criminal Law as a Countermeasure for White Collar Crime (Money Laundering)/Primum Remedium Dalam Hukum Pidana Sebagai Penanggulangan Kejahatan Kerah Putih (Money Laundering). Lex Crimen 10: 197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiarto, Umar Said. 2013. An Introduction to Indonesian Law/Pengantar Hukum Indonesia. Jakarta: Sinar Grafika. [Google Scholar]

- Syahuri, Taufiqurrohman, Gazalba Saleh, and Mayang Abrilianti. 2022. The Role of the Corruption Eradication Commission Supervisory Board within the Indonesian Constitutional Structure. Cogent Social Sciences 8: 2035913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transparency International. 2023. Corruption Perception Index Indonesia 2023. Available online: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2023/index/idn (accessed on 29 February 2024).

- Turner, Mark, Eko Prasojo, and Rudiarto Sumarwono. 2022. The Challenge of Reforming Big Bureaucracy in Indonesia. Policy Studies 43: 333–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuni, Made Arie. 2011. Tax Evasion: Dampak dari Self Assessment System. Jurnal Ilmiah Akuntansi dan Humanika 1: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waluyo. 2011. Indonesian Taxation/Perpajakan Indonesia, 9th ed. Jakarta: Salemba Empat. [Google Scholar]

| Investigation Completed/Terminated | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completed/P21 (Filed to the Prosecutor) | 124 | 138 | 97 | 93 | 98 | 550 | 82.2 |

| Terminated by Art. 44A General Provisions and Tax Procedures or GPTP Act (by law) | 0 | 1 | 3 | 12 | 3 | 19 | 2.8 |

| Terminated by Art. 44B GPTP Act (Paying Taxes and Fines at Investigation Stage) | 3 | 6 | 3 | 10 | 16 | 38 | 5.7 |

| Terminated by Art. 8(3) GPTP Act (Paying Taxes and Fines at Preliminary Investigation Stage) | 2 | 3 | 5 | 20 | 32 | 62 | 9.3 |

| Total | 129 | 148 | 108 | 135 | 149 | 669 | 100 |

| Description | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preliminary Investigation | 1071 | 1240 | 1312 | 1243 | 1234 |

| Tax Investigation | 245 | 318 | 248 | 210 | 233 |

| Filed to the Prosecutor/P21 | 124 | 138 | 97 | 93 | 98 |

| State Losses Value (in Billion IDR) | 1354 | 991 | 575 | 1970 | 1634 |

| Options | Explanation | Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Current policies (UR policies) | This policy is overly oriented to taxpayer interests. Administrative sanctions will be the primary tool to be imposed, instead of criminal sanctions. There are boundaries and many facilities along the law enforcement process for tax offenders to be released from legal bondage if they have money to pay the embezzled taxes and the fines. | Indonesia will face increased tax crime cases that can undermine the law, harm the sense of justice, lower the government’s authority, not create a deterrent effect, and trigger rampant tax crimes. |

| Alternative policies (PR policies) | This policy is oriented to legal interests and is not in line with the rules of administrative penal law. Criminal sanctions will be the primary tool to be imposed for all kinds of violations, whether the violations are light or severe. There are no boundaries and facilities for tax offenders along the law enforcement process. | This will cause commotion, frighten the taxpayers and investors, as well as be counter-productive with regards to tax and legal interests. Implementing this policy will be complicated. The DGT will face difficulty processing tax violations, as a result of inadequate resources. |

| Proposed policies (combined UR and PR policies) | Based on this policy, administrative and criminal sanctions will be imposed better. There will be boundaries between the end of the preliminary investigation and the investigation. The facilities will still be offered until the end of the preliminary investigation, as the last chance to be released from legal bondage and imprisonment. However, severe punishments will be imposed on the tax offenders who proceed with the law enforcement process and are found guilty in court. | This policy will harmonize the interests and objectives of both tax enforcement and legal principles. By allowing tax offenders to settle their duties, the state can recuperate tax revenue while maintaining social justice. The DGT will benefit by reducing the number of tax crime cases filed to the subsequent law enforcement process, if tax offenders utilize the provided facilities. The tax offenders themselves benefit from lighter fines imposed under these policies, compared to current regulation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nurferyanto, D.; Takahashi, Y. Establishing Boundaries to Combat Tax Crimes in Indonesia. Laws 2024, 13, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws13030029

Nurferyanto D, Takahashi Y. Establishing Boundaries to Combat Tax Crimes in Indonesia. Laws. 2024; 13(3):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws13030029

Chicago/Turabian StyleNurferyanto, Dwi, and Yoshi Takahashi. 2024. "Establishing Boundaries to Combat Tax Crimes in Indonesia" Laws 13, no. 3: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws13030029

APA StyleNurferyanto, D., & Takahashi, Y. (2024). Establishing Boundaries to Combat Tax Crimes in Indonesia. Laws, 13(3), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws13030029