Abstract

The European financial regulation is evolving with new and specific forms of cooperation for the member states, enhancing concepts and innovative rule of law, particularly featuring the actual level of harmonization. This paper investigates the European deposit insurance scheme, in the context of the European law development, in reply to the current economic and social challenges and in accordance with the principles of the free market. The methods of research include a theoretical investigation of the relevant literature, a comparison of the proposed regulation and regulation in force, synthesis, and deduction. The research results are based on the assessment of the progress of negotiation in building efficient mechanisms to stimulate money saving conduct for individuals and legal persons, globally and within the European Union. Acknowledging the status of the three pillars of the European banking union legislative package, the member states have unanimously agreed that the framework established by the Directive from 2014 needed a bracing approach, to ensure more protection and to support enhanced financial integration. The analysis carried out showed the importance of the European deposit insurance scheme in the context of the present global challenges. The money saving conduct was strongly influenced by the regulation for the deposit guarantee mechanism, while the tight estimated agenda for the final regulatory proposal asks for ingenious cooperation to reach a consensus within members states. The research showed the imperative to build common legislation for the member states and a future direction of investigation to evaluate the effects of the gap between the domestic regulation and milestone generated by the European directives in each state legal framework.

1. Introduction

All recent crises (financial events of the last decade, COVID-19 pandemic, Ukrainian war, and the energetic global disorder) have brought a great stress on the financial markets, influencing the general conduct of the deponents. The trust of the public in bank services is challenged especially when liquidity of the markets diminishes, and businesses are exposed to insolvency scenarios. The deponents act with prudence in relation to the banking system, looking for addition tools to protect their wealth. The methods to increase or at least to stabilize the financial institution liability in front of their clients include extended guarantees that the debts previously engaged are still honored, even in the worst possible situation the institution might face. The deposit guarantee schemes (DGS) are regulatory mechanisms used for this purpose, based on the insurance to reimburse a precise limit of the deposits to the owners, when the bank is not able to do so objectively. This mechanism aims at strengthening the financial institution credibility; consequently, a large majority of the banks have chosen such protection, paying specific contributions, calculated mainly on the consideration of their activity risk profile.

The purpose of this mechanism is embraced by both the credit institution and their clients, and the regulation to have it applicable is continuously upgrading, for the scope of eliminating the vulnerabilities of the system and offering stronger protection to the ultimate beneficiary, i.e., the owner of the bank deposit. Although the use of the deposit insurance scheme is validated in extreme crises situations for the financial institutions, its main effects are to upgrade the credibility and the efficiency of the respective financial institution activity which, eventually, will not have to face the abovementioned crises. The importance of the effect is obvious for each client of the banking system and for the banking system, as a whole.

At the EU level, the deposit insurance scheme is a subject with high financial impact and relevance at the level of each member state and of European Union concern, as one of the indirect effects of the internal market mechanisms.

This paper contributes to the scholarly literature assessing the concept of the deposit insurance system in the current global regulatory context, pointing out its evolution and the need to respond to the actual global challenges on the financial market. The issues whether there is a need for general legal framework in the field of mechanisms to reinforce clients’ trust in bank activity and if there is the possibility to address it in the next decade are investigated and answers are formulated. First, the paper adds to a narrow yet developing body of literature on regulation for deposit insurance systems, elaborating a comparative analysis of regulatory systems and positioning the current study within the ongoing debate in favor of the common regulatory framework. Second, our work adds to the literature on European depository insurance scheme actual proposal, by examining the positive and negative aspects raised. Third, this paper expands the literature on the topic, presently dominated by financial analysts and economists, adding a view for legal scholars.

This paper aims to bring insight into and emphasize the pros and cons of the ongoing discussion on the actual issues connected with the recent developments of European deposit insurance schemes. The analysis starts with a review of the available literature (Section 2) and continues with a presentation of the evolution of deposit insurance scheme regulation, emphasizing their mandatory features and some particularities adopted in different periods of the recent development of the specific regulation (Section 3). The adoption and the evolution of the European depository insurance scheme legal framework are addressed (Section 4), formulating some answers to the current challenges of the mechanism of deponents’ protection in the conclusions (Section 5). The principal methods of research used in the paper are theoretical investigation of the relevant literature, empirical research, observation and comparison of regulations in force, synthesis, and deduction.

2. Literature Review

Within the financial system, banks hold the central role in a country’s payment and settlement transaction (Åberg et al. 2021), and they can play an important role in the conduct of monetary policy, which works through financial institutions and markets to affect the economy (IMF 2022; Ketcha 1999). Providing liquid savings vehicle while addressing the needs for small and large investors alike (Palenzuela and Dees 2016) and developing specialized skills to evaluate and diversify the risks of their borrowers (Grundl et al. 2016), banks have played an important role in promoting economic growth and sustainable development worldwide (Levine 1997; UNCTAD 2017). The nation’s economic vitality depends critically on the soundness and the competitiveness of the banking system (Paun et al. 2019).

Banks have traditionally performed the important function of intermediating between lenders and borrowers using liquid, short-term liabilities to fund relatively long-term, illiquid assets (Khundadze 2009). Within the regulation for banking activity, deposit insurance systems (DISs) are initiatives aimed at addressing threats related to the failure of deposit-taking financial institutions (Adema et al. 2019), and most countries have adopted such regulations, aiming at different objectives, and using different features (Demirgüç-Kunt et al. 2014). For some of the countries that have adopted this type of regulation, recent developments have pointed out areas in which the effectiveness and efficiency of structures could be improved (Schich 2008). Others considered that the motivation for using this mechanism was stronger than the prudency imposed by the current evolution of the financial markets (Mauro et al. 2013). The recent financial turmoil provided supervisory, regulatory, and other financial policy authorities with a timely opportunity to review existing regulatory structures (TC 2017), underlying the operation of financial markets (Carmichael et al. 2004), including those related to providing or reinforcing financial safety (Lumpkin 2009).

The regulation of the deposit insurance system (DIS) is the most frequently used method to bring certainty to the depositors for collecting their money, even if their bank collapsed (Arda and Dobler 2022). Traditionally, relevant studies on the DIS state that, together with the prevention against losses for individual depositors, DIS limits the incentive to withdraw deposits before other depositors do so (Garcia 2000; Diamond and Dybvig 1983; Calomiris 1989). The literature shows that Google searches for “deposit insurance” and related strings reflect depositors’ fears and help to predict deposit shifts in the German banking sector from private banks to fully guaranteed public banks. After the introduction of blanket state guarantees for all deposits in the German banking system, this fear-driven reallocation of deposits stopped (Fecht et al. 2019).

DISs help to keep the problems of one bank from spreading to the whole sector (Nolte and Khan 2017). As banks are a country’s main source of finance, having a stable and well-functioning banking sector is important for a country’s economic development (Anginer et al. 2014). Furthermore, in nowadays globally integrated capital markets (Azis and Shin 2015), a country without a DIS might encounter outflows of deposits (Obstfeld 1998), both regionally and globally (Laeven 2014). The benefits of the efficient deposit insurance scheme evolved into the observation of the economic problem of moral hazard (Pauly 1968; Pettinger 2019), presented in the literature from two perspectives. First, DIS is the mechanism that gives incentives to banks for high-risk investments (Kotowitz 1989), since economic profits from higher risk-taking are privately captured by the banks, while losses are socialized through the deposit insurance fund (Berger et al. 2019, p. 695). Second, depositors who are guaranteed the money when a bank fails (Dembe and Boden 2000), lose their interest to monitor the financial condition of their bank (Anginer and Demirguc-Kunt 2018).

Although there is a large opinion that the common or at least harmonized regulation is recommendable (Tofan and Bostan 2022), relevant literature in the field addresses the deposit insurance systems established in line with IMF work on the subject (Arda and Dobler 2022; Phillippe et al. 2014) and argues against the development of “best practices” applicable to all systems (Hoelscher et al. 2006). The features of each country’s specific objectives in adopting a deposit insurance system is emphasized, together with the importance of incorporating the guidelines of the international expertise into domestic regulation (Hoelscher 2016) and with the need to pay attention to the country’s financial system characteristics (Salama and Braga 2021). The goal of the regulation is to ensure an effective banking system that minimizes disincentives and distortions to financial sector intermediation (IADI 2010).

The desirability of deposit insurance scheme regulation remains a matter of controversy, which is present in ongoing debates (Chu 2011; Calomiris 2016). Several scholars question the usefulness of deposit insurance on the grounds that it could involve moral hazard problems (Gropp and Vesala 2001; Hellmann et al. 2000; Cull et al. 2005). This could result in excessive risk taking on the part of depositors, as well as the banks accepting the deposits (Schich 2008). The present research adds to this flux of debate with respect to some arguments and identifies additional appropriate lines of action in future research.

3. Argument for Deposit Insurance Scheme (DIS)

In the present economy, dominated by digitalization and stigmatized by unpredictable global threats (world pandemic, wars with nuclear potential, survival migrations, energy and fuel crisis, etc.), the stability of the financial system is crucial for the relative normality of the people lives.

For this purpose, there have been some mechanisms set up by active regulation, to reduce the vulnerability of the financial system, for both its private and public components (ECB 2022). Especially in the economies where payments are mostly online and money is used mainly in electronical form, the bank–client relationship is not only a growing partnership for every legal subject, but continuous and mandatory. Although it is present in many of the everyday actions, the fluidity of the relationship between clients and banks depends on the credibility of the respective financial institution, not necessary in terms of macro- and micro-financial analysis and criteria, but on the personal level.

The major concern of clients is connected to the individually evaluated bank capability to pay back collected money, at any time and in any circumstances. The worst possible scenario might occur when bank depositors grow so anxious about their financial security regarding the money placed in a specialized institution so they decide suddenly and in a relatively synchronized manner to ask for their cash to be returned. This type of impetuous request would result in the respective bank struggling to honor the legitimate withdrawal requests and could lead to destabilization or even to the financial collapse of that institution.

This is the context where the need for an efficient method to build trust is obvious, while the banks largely rely on clients’ deposits to develop further activities, and their success depends on their capability to collect as much liquidity as possible on the financial market where they are active. Instruments to reinsure public trust have been developed, including deposit insurance (Barth et al. 2013). Such a tool is the proper response, if it proves able to fulfill two major priorities (Bernet and Walter 2009), directed toward protecting the stability of the system (upper level), and directed toward consumer protection (lower level of applicability).

First, DIS is meant to protect the clients of the banks from the risk of not collecting back the money they have placed in banks, preventing massive money withdrawal by clients in panic. This scenario would support, in its extreme intensity moment, the decision to transform the assets of the respective bank in cash. An extensive and sudden sale procedure of the goods of the bank would take place as part of the liquidation of the business, and, in these types of procedures, a less than necessary amount of money is eventually raised, at a very low price. This situation could force illiquidity and insolvency of the bank (Delis et al. 2012), because the actual value of the asset is considerably different than the value considered in the bank business plan, before the conditions that generated the panic of extensive withdrawal requests. Such events are destructive for the bank client’s financial wealth and for the banks themselves, while they have a bad influence on the financial sector stability and on the economy of the countries where the respective bank is present. To prevent them, the mechanism of DIS is useful. From this perspective, the main goal of a deposit insurance scheme is to reduce as much as possible, if not eliminate, the risk of bank bankruptcy. This goal represents the most frequently used argument in favor of bank using deposit insurance systems, outbalancing the endemic possibility of the extended effect on the national financial system in the country of embodiment of that bank. In the context of the European single market and the regulation of fundamental free circulation of people, goods, and capital, such effects would most probably extend beyond the territory of one country only, indirectly affecting the banking systems of many nations.

The secondary goal of regulating a proper DIS is to protect small depositors from losses, as DIS should cover (up to a precise threshold) the financial effects supported by depositors generated by a banking institution in difficulty to honor legitimate withdrawal. In fact, the mechanism of a deposit insurance systems offers a double protection for getting back the money placed in banks, with a second option to collect the money that the depository wants to withdraw, indifferent of the banking financial condition at a particular moment, thus eliminating the risk that depositors placing funds at a financial institution suffer unjust loss (Ketcha 1999). Analyzed from this double perspective (bank and client), the DIS is more of a guarantee against a loss than insurance (Anginer et al. 2014).

There is the possibility that both the perspectives and the direct positive effects of the deposit insurance scheme described above are sometimes unbalanced by the risk that negative effects become incident in the situation where the DIS is applicable. One possible negative effect, the “moral hazard” concept, emerged in the field of financial services, precisely the insurance area, since, when insurance is applicable, it usually changes the action of the beneficiary of the protection mechanism.

In banking operations, the moral hazard possibly appears when the involved financial institution has liquidity problems, which are not actively manifested yet, but some changes are reflected in the incentives offered to the clients. In general, the private insurance schemes offer protection for possible risks which are precisely presented, eliminating from the scope of the insurance specific situations, i.e., the situation of suicide from life insurance payments. Deposit insurance covers depositors against losses resulting from any type of bank failure, regardless of the reason for that failure. (Anginer and Demirguc-Kunt 2018). These types of limitations are designed to reduce or to cancel the payments. Deposit insurance in this respect is not really insurance in the common usage of the term but more of a guarantee against loss.

The moral hazard behavior may affect the depositors when, for instance, they choose to insure their deposits accepting the offer with higher interest rates, without considering that this comes in the same package with higher risks. The prudent action for a client would be to give priority to the solidity of the deposit insurance and not to the potential higher income.

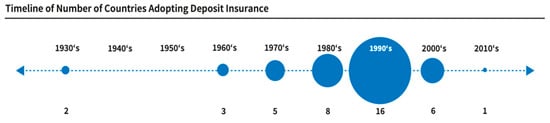

Proving that the positive effect of DIS outbalances the negative impact, many financial regulatory systems globally include mechanisms to reply to these challenges, starting with the United States in 1933 and continuing as revealed in Figure 1. The effects of the crises during the 1980s and 1990s led to a growing number of countries initiating or considering the institution of an explicit system of deposit insurance (Garcia 1999).

Figure 1.

Source: (Adema et al. 2019, p. 42).

The dynamic of regulatory development for DIS is predicted to evolve with increased speed within the EU, where the need for this regulation is no longer debated, while the precise rule of law still is, as revealed in the next section of this paper.

The globalization of the economy and the internationalization of the financial services market have stimulated international cooperation in the DIS field, highlighting the necessity to build the Association of Deposit Insurers (IADI), a worldwide organization for deposit-insuring institutions which promotes cooperation and encourages contact among deposit insurers and other interested parties (IADI 2018). The participants are institutions built in each member state to monitor, control, and coordinate the depository insurance systems, designated with the acronym DIA (deposit insurance agencies). There are two main categories of member parties in this association: IADI members (which are the deposit insurance organizations for each member) and IADI associates (which can be different institutions in each member states that have created autonomous deposit insurance mechanisms). Additionally, there is the group of the IADI observers, which reunites various interested legal entities, international organizations, financial institutions, or professionals with common interest in the deposit insurance features and regulation. Alongside these internal structures, there are IADI partners, legal entities that have concluded a specific arrangement with IADI, expressing their adhesion and support to pursue the IADI’s objectives.

Recently, an investigation carried out by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation in United States (FDIC) proved that, even during financial crises, when losses are above 20%, there is a very low risk of the bank insurance fund becoming insolvent (FDIC 2022). There were 561 American bank failures from 2001 through 2022 and the research was based on the bank insurance fund’s historical loss experience (FDIC 1998). The results showed that there is no guarantee that future banking crises will mirror historical events, given recent industry consolidation and the regulatory developments, including the deposit insurance scheme. It is our observation that the soundness of the banking sector was transferred to the insurance market. It is more efficient for an insurance fund to have stability according to the valid option to recover in a longer period, previewed in the regulatory framework, thus offering stronger protection to the potential beneficiary, when severe threats are present.

On the contrary, banks’ capability to manage the long-term assets and to grow deposits with high liquidity are competences of great value in the undesirable scenario when many clients decide to claim their cash in a short period of time or, even worse, at the same time (Calvin 2022). It is not quite relevant if the motivation of the clients is realistic or is in connection with the information on the bank assets; the resulting effect could be equally disastrous. The economic benefits of transformation of assets to liquidity are best achieved if the demand of the client to collect their cash is specially addressed for deposits at maturity or in the eventuality when the bank can be used as a medium of exchange, i.e., when savers could exchange their demand deposits with others in the economy (Dang et al. 2014). While it is expected that demand deposits function on a short-term basis and they hold priority over other legitimate requests, they are less vulnerable to the sudden changes in available information on assets of the financial institution (ECB 2022).

The reviewed literature, both traditional (Gorton 1988; Jacklin and Bhattacharya 1988; Allen and Gale 2000) and more recent (Popescu 2022), is constant in expressing that a decline in the value of the assets held by banks most likely would cause depositors to withdraw funds from the bank. It is equally mandatory to observe that the success of the deposit insurance directly depends on the level of trust that the clients admit and invest in the insurance scheme. As the legitimate claims of the clients for collecting their cash from the demand deposits are served on a first-come first-served basis, the conduct of the depository to act impulsively immediately after the information on depreciation of bank assets becomes available for the public. If the bank runs out of reserves and is forced to suspend withdrawals, depositors at the front of the line could receive all their funds while those at the end of the line could receive nothing (Anginer and Demirguc-Kunt 2018).

If the bank clients consider that the risk of the insurer to go insolvent exists, then the action for withdraw the deposits is not only valid, but also predictable and imminent (Buckingham et al. 2019). We need to observe that the nature of the insurance mechanism is, at the same time, responsible for the common knowledge that there are no sufficient funds for covering all potential risks at the same time.

At this point in our analysis, two paths of investigation are simultaneously opened, in order to identify the right answer to the following problems:

- -

- How to manage the dissemination of information to the bank clients in such a timeline to maintain the payments as continuously as possible,

- -

- How the state authorities can intervene by creating an additional supporting mechanism for the existing deposit insurance schemes to hold on when a severe risk is present.

During a financial crisis, there are several episodes that have threatened the credibility of deposit insurance schemes in some countries (Anginer and Demirguc-Kunt 2018). The political leaders in the responsible authorities of the state are asked to intervene, a solid and prompt adjustment procedure is required, and, more importantly, the state should have the budgetary income to take the efficient actions to refund the losses, to preserve (or reinstall) the financial stability (Popov 2017). In countries with large banking sectors and deteriorating public finances, intervention is not always a viable option, and underfunding is a real possibility (BIS 2011).

Establishing the proper level for the deposit insurance is a milestone in the process of maintaining clients’ trust in the financial system. The level of the fund is crucial in providing the adequacy of the deposit insurance and depends on certain country-specific conditions (IADI 2018, p. 44). There are mandatory conditions to be observed for drawing an effective level for the deposit insurance system, which include the following:

- A stable and sound regulation;

- A functionable macroeconomic environment and pertinent and efficient public policies for insuring secure and solid banking system;

- A financial system characterized by appropriate regulation and effective supervision;

- High degree of conformability to the standardized accounting, auditing, and regulatory framework;

- A valid disclosure regulation.

Ideally, all these conditions are met before deposit insurance is regulated, yet some of them may not be present, and attention needs to be paid to the precise coping mechanism for the respective deposit insurance system to be successful. Observing that volatility of the financial markets increased during this century (Lambert 2022), it might be unlikely to draw long-term applicable conclusions regarding the effects of any financial crisis. Nonetheless, first lessons are emerging concerning the need for a large mutual agreement regulatory framework (Tofan 2022), built on the national and international negotiations on the appropriate policy measures, including those affecting the financial safety net, formulated two decades ago (Schich 2008).

4. European Regulatory Framework for DIS

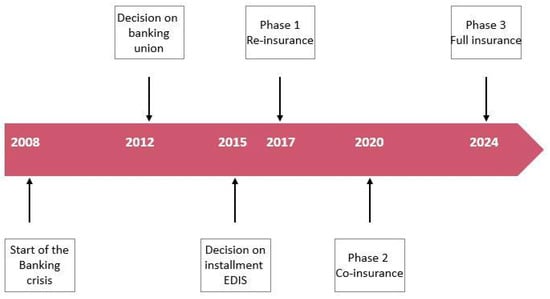

In this international context, it is important to assess the framework of deposit insurance scheme regulation within the European Union, where the topic is under ongoing debate since the financial and banking crises in 2008 and was relaunched with the decision on the proposal for a banking union (see the timeline in the Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Source: (Sia Partners 2022).

The actual debated issue is the limit on average deposit rates, proposed to be raised by the provision of 2009/14/EC directive, which already increased this limit from 20,000 to 100,000 EUR. When the multilateral regulation has the tendency to be postponed, the unilateral action is in place (Tofan 2021). We can notice in this respect the fact that the limit was already increased in Italy (starting with 1994), and the average deposit rates decreased substantially among banks in the EU relative to banks in Italy (Gattia and Oliviero 2021). It is our opinion that the narrative of debate supports the harmonization of the regulation regarding the limits of the deposit insurance, one of the primary phases to build up a unique framework for the European deposit insurance scheme and to sustain the mechanisms of the EU banking union (Garonna et al. 2021). Different deposit scheme configurations directed national policy on the difficult revision of the deposit insurance directive, and emphasis was placed upon moral hazard in the formation of national preferences on the European deposit insurance scheme (EDIS) (Howarth and Quaglia 2018).

In this line of action, in November 2015, the European Commission launched the proposal of regulation for European deposit insurance scheme (EDIS), which was presented together with the procedure to implement this regulation, considered the third pillar of the banking union. The procedure includes three stages.

Initially, during the first 3 years (July 2017 to July 2020), it was established that the deposit scheme includes up to 20% of the lack of liquidity and up to 20% of the prejudice exceeding the level for the institutions included in the scheme, in all cases when the legitimate payments overlap the disposable financial resources. Legally, the need for liquidity is supposed to be supplemented using the loan mechanism; hence, the deposit guarantee scheme DGS has to pay the amount back, except for the reinsured part of the excess loss (i.e., 20%), which would not have to be paid back. A targeted measure to limit the moral hazard is to limit at 20% of the deposit insurance fund DIF’s initial target level of the reinsurance funding or 10 times the target level of the insured DGS, whichever is lower. In addition, the benchmark for calculating whether and to what extent a DGS can access the EDIS during the reinsurance phase is the hypothetical level of liquidity the DGS should have, if it had complied with all its obligations (e.g., collecting ex ante contributions to reach the target level), and not the actual level of liquidity in a DGS (De Lisa 2016). Lastly, other sources available to the DGS (e.g., raising short-term ex post contributions) have to be tapped before resorting to EDIS, and the SRB is mandated to monitor the way the DGSs pursue their claims during insolvency proceedings. During the reinsurance stage, banks’ risk-based contributions to the DIF are calculated with reference to the national banking system, i.e., relative to the riskiness of banks in the same country and not of all banks in the banking union (European Commission 2018).

In the second phase, which is supposed to expand for the 4 years following the reinsurance stage up to July 2024, the coinsurance scheme is designed to payback a steady growing part of the loss (20% during the first year, 40% during the second year, 60% during the third, and 80% during the fourth) for all DGSs members. The procedure is based on the coinsurance participation for every payment, not in connection with the status of the domestic financial institution solvability. Consequently, any payments would imply domestic and reinsurance co-participation, and the legitimate request for reimburse is to be forwarded by the national DGS. We explained already that the money provided to the DGS would have to be repaid based on loan mechanism. Yet, this is not applicable for the money paid to compensate for the suffered loss, which would be allocated by the national DGSs and DIF, accordingly with the increasing ratio provided in the regulation. In this way, the proposal affects not only the financial sector actors, but the whole entities active in the respective economy. The particularity of the coinsurance phase is that it differs from the reinsurance phase because the risks of the banks are measured against the riskiness of all banks in the banking union.

The final stage (the third phase) is programmed to be launched in July 2024, as a results of successfully implementing of the reinsurance and coinsurance procedures for 7 years. We note the length of the two phases, identical to the multiannual provisional budget of the EU. During the final stage, the full insurance scheme is expected to be active, and the EDIS to be applicable for entirely recovering the financial losses and supplying the amount of money required by the participant institutions in the deposit insurance mechanism. It is expected that, eventually, at the end of the three steps, the potential losses to be entirely covered through the DIS, using reinsurance and coinsurance as principal methods to share the risks among the involved financial institutions. The final goal is to eliminate the possibility of using a threshold by reducing if not even canceling the impact of the potential moral hazard for the depository within the EU.

In October 2017, the European Commission published a communication on the completion of the banking union (European Commission 2017), including a proposed new approach on EDIS aimed at addressing diverging views in the European Parliament and the council. The commission decided to slow down the rhythm of implementing the EDIS described in the above-assessed three-step procedure. It was proposed that, during the reinsurance phase, there would be no actual payments for the losses, even though the coverage of the lack of liquidity could be growing progressively to 90% in the third year. The start of the coinsurance phase (the second stage of the procedure) depends on validation of certain criteria by the European Commission, e.g., related reduction in banks’ portfolios of nonperforming loans and level 3 assets, i.e., illiquid assets which cannot be evaluated because of market prices or models (European Commission 2017). If the commission certifies the beginning of the coinsurance stage, it is previewed that EDIS offers support for potential losses, from an initial rate of 30% of the total loss, which should steadily increase. It is important to observe that the European Commission communication does not include minimum necessary details about the increasing procedure (rate, period, etc.); thus, we consider that this expected increase is only potential, not a real fact. Depending on the endpoint of the progressive increase in losses coverage, the final stage could be closer to or more distant from a fully fledged EDIS with full insurance. As the communication indicated that the original proposal “remains on the table unchanged”, full insurance in the steady state remains a possibility to be discussed by co-legislators (Carmassi et al. 2018).

We consider that the right and sufficient size of the participants’ contributions to the DIF is one of the most important subject to agree on with high impact not only on the architecture of the scheme but also on the success of the overall mechanism. The amount itself is important, as is the algorithm to share it among the institutions implied in the procedure, both when building the scheme and when making use of its action. Considering the specificity of the European internal market, the freedom in banking services, and the free movement of capital, there is the legitimate question if the effect of EDIS could lead to unregulated situation when the banks in one member state are involved in the payment procedure for insolvency of the financial institutions in another member state of the EU.

In addition to all the arguments in favor of adopting the proposal, we observe some limitations to be addressed in the future by mutual agreement and to be solved at national level, for the time being. The proposal for regulation seems extensive, yet it does not provide protection for all deposits. The European law aims at offering full protection only for deposits within the threshold of maximum level of coverage of 100,000 EUR per depositor per bank. This level is mandatory and included in the regulation in force for all member states. Consequently, retail deposits of small, less sophisticated investors would be insured, but wholesale deposits of large, sophisticated investors would not, in order to strike an appropriate balance between protecting depositors’ trust and financial stability, on the one hand, and preserving market discipline and limiting moral hazard, on the other hand (Carmassi et al. 2018).

The Directive 2014/49/EU defines the concept of “covered deposits” using the deposit guarantee for them up to the 100,000 EUR coverage level; other protected deposits include the following:

- Pension schemes of small and medium-sized businesses;

- Deposits by public authorities with budgets of less than 500,000 EUR;

- Deposits of over 100,000 EUR for certain housing and social purposes.

We observe the indirect consequence that the deposits in other banks and financial institutions are not eligible for coverage. The effect of this limitation is to prove that the DIS offers effective protection only for the depository in need of such intervention, where the depository is assumed to be dramatically affected by a loss in their money temporarily placed in a financial institution. The explanation is beyond the fundamental goal of the rule of law (i.e., protecting the weak, as the strong gets protection alone), but it is aimed at strengthening the rigor and law risk operations on financial market for all those unprotected, big, and sophisticated investors, contributing to the efficient management of the moral hazard. In this way, DGSs are determined to use efficient and transparent governance good practices.

The proposal affects in various ways the deponents depending on their financial wealth, private individuals, companies, and public institutions, leaving some room for national policy to decide on elaborating in-depth legislation for the proper applicability for the European legal framework. After 2015, the regulation established the time limit for paying the legitimate claim of the depositors in 20 working days, and this limit must be progressively reduced to 7 working days by 2024. When a certain depositor specifically asks for it, a small amount could be paid out earlier, if the particular deposit guarantee scheme is not capable to honor the requests up to the 7 day limit. This is considered a transitory justified exception, applicable only by 31 December 2023, as the 7 day limit is previewed to become mandatory for all legitimate claims starting 2024. The funds of deposit guarantee schemes come from the banking sector. The amount of this exceptional payment is mainly determined by the respective bank risk profile and its contribution to the fund (which is normally proportional with its diagnosed risks).

5. Conclusions

In response to the risk supported by the depository in relation to their banks and because of the recent financial crises, there have been propositions to identify the efficient, sound, and transparent mechanism to provide strong security support for the clients of the financial institution. Recent regulatory initiatives at the EU level (European deposit insurance scheme) describe a simple method to cover the potential loss from bank insolvency, despite the causes of the financial difficulties of that financial institution.

First, in the context of this proposal, the commission published an effect analysis on EDIS concluding that it is more efficient to pool the financial risks present on the European market in terms of producing a much stronger deposit guarantee scheme than a mechanism applicable at national level. Analyzing the information provided in the study of the commission, we observed the need for further discussion on related possible scenarios and how would they be managed by the proposed regulation. The paper conducted empirical analysis to assess whether and for what specific conditions such regulation is appropriate and sufficient.

Second, we highlighted that a heterogeneous insurance of deposits can generate unexpected and unjustified conduct for depositors, shaking the stability of the financial market and jeopardizing the banking activity. The research pointed out how different mechanisms of insuring risk-based deposit affect the distribution of positive effects across countries, increasing the gap between banking systems within the EU. In this way, the subject protected by DIS (i.e., small and unsophisticated depositors) are ultimately affected by the changes in the banking sectors in different member states. The common approach for all the European actors is the most efficient, sound, and sustainable solution for protecting the depositors throughout the EU. The paper shows that the national preferences for DIS are to be abandoned in favor of the EDIS, a different configuration of existing national DGS. The effort is consistent, as national DGS are linked to the different configuration of national banking systems, but the estimated results pay off.

Third, there is the influence of moral hazard highlighted repeatedly by the literature and practitioners, concerning the manageability of real and possible bank losses. Furthermore, the concern regarding the financial cost of the national banking systems when contributing to the EDIS was formulated by some European member states. The obligation to execute potential financial transfer using the banking system and not the public wallet was a challenge for policymakers in these countries.

Despite this strong opposition to the creation of an EDIS and although its mechanism has been intensively argued and debated, its regulation is steadily and constantly developing, and its long-term benefits for financial stability purposes prevail.

Limits of the research draw further investigation directions, such as the effects of the deposit insurance scheme on computerization, proper organization of administration, and resource management.

Funding

The author acknowledges financial support from the Romanian National Authority for Scientific Research and Innovation, CNCS–UEFISCDI—Project PN-III-P4-ID-PCE-2020-0929 Household Saving Behavior—A Socio-Economic Investigation from Households, Banks, and Regulators Perspective.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Åberg, Pontus, Marco Corsi, Vincent Grossmann-Wirth, Tom Hudepohl, Yvo Mudde, Tiziana Rosolin, and Franziska Schobert. 2021. Demand for Central Bank Reserves and Monetary Policy Implementation Frameworks: The Case of the Eurosystem, European Central Bank Occasional Paper Series, no. 282/2021. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecb.op282~6017392312.en.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Adema, Joop, Christa Hainz, and Carla Rhode. 2019. Deposit Insurance: System Design and Implementation across Countries. IFO Dice Report 17: 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Franklin, and Douglas Gale. 2000. Financial Contagion. Journal of Political Economy 108: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anginer, Deniz, Asli Demirguc-Kunt, and Min Zhu. 2014. How Does Deposit Insurance Affect Bank Risk? Evidence from the Recent Crisis, Policy Research Working Paper 6289. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/12186/wps6289.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Anginer, Deniz, and Aasli Demirguc-Kunt. 2018. Bank Runs and Moral Hazard a Review of Deposit Insurance, Policy Research Working Paper 8589/2018. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/30444/WPS8589.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Arda, Atilla, and Marc Dobler. 2022. The Role for Deposit Insurance in Dealing with Failing Banks in the European Union. IMF Working Papers 22/2. Washington, DC: IMF. [Google Scholar]

- Azis, Iwan J., and Hyun Song Shin. 2015. Managing Elevanted Risks, Global Liquidity, Capital Flows, and Macroprudential Policy—An Asian Perspective, Springer Open. Available online: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/150174/managing-elevated-risk.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Bank for International Settlement (BIS). 2011. The Impact of Sovereign Credit Risk on Bank Funding Conditions, CGFS Papers 2011/No 43. Available online: https://www.bis.org/publ/cgfs43.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Barth, James R., Cindy Lee, and Triphon Phumiwasana. 2013. Deposit Insurance Schemes. In Encyclopedia of Finance. Boston: Springer, pp. 207–12. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Allen N., Philip Molyneux, and John O. S. Wilson. 2019. The Oxford Handbook of Banking. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bernet, Beat, and Susana Walter. 2009. Design, Structure and Implementation of a Modern Deposit Insurance Scheme, SUERF—The European Money and Finance Forum Vienna. Available online: https://www.suerf.org/docx/s_6547884cea64550284728eb26b0947ef_2437_suerf.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Buckingham, Sophie, Svetlana Atanasova, Simona Frazzani, and Nicolas Veron. 2019. Study on the Differences between Bank Insolvency Laws and on Their Potential Harmonization, European Commission Final Report. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/business_economy_euro/banking_and_finance/documents/191106-study-bank-insolvency_en.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Calomiris, Charles W. 1989. Deposit Insurance—Lessons from the Record, Economic Perspectives, 1989/5. Available online: https://www.chicagofed.org/~/media%2Fpublications%2Feconomic-perspectives%2F1989%2Fep-may-june1989-part2-calomiris-pdf (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- Calomiris, Charles. 2016. Deposit Insurance: Savior or Subsidy? Harvard law School Forum on Corporate Governance. Available online: https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Calvin, Patricia. 2022. Turbulence and the Lessons of History-Opportunities are born of crisis, but the lines that connect them are far from direct. Finance & Development, International Monetary Fund 59: 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Carmassi, Jacopo, Sonja Dobkowitz, Johanne Evrard, Laura Parisi, Andre Silva, and Michale Wedow. 2018. Completing the Banking Union with a European Deposit Insurance Scheme: Who Is Afraid of Cross-Subsidisation? European Central Bank Occasional Paper Series No. 208/2018. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecb.op208.en.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Carmichael, Jeffrey, Alexander Fleming, and David T. Llewellyn. 2004. Aligning Financial Supervisory Structures with Country Needs. WBI Learning Resources Series; Washington, DC: World Bank Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Kam Hon. 2011. Deposit Insurance and Banking Stability. Available online: https://ciaotest.cc.columbia.edu/journals/cato/v31i1/f_0021598_17861.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Cull, Roberty, Lemma W. Senbet, and Marco Sorge. 2005. Deposit Insurance and Financial Development. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 371: 43–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Viet Anh, Minjoo Kim, and Yongcheol Shin. 2014. Asymmetric adjustment toward optimal capital structure: Evidence from a crisis. International Review of Financial Analysis 33: 226–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lisa, Riccardo. 2016. The Changing Face of Deposit Insurance in Europe: From the DGSD to the EDIS Proposal. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308891172_The_Changing_Face_of_Deposit_Insurance_in_Europe_From_the_DGSD_to_the_EDIS_Proposal/citation/download (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Delis, Manthos D., Georgios P. Kouretas, and Chris Tsoumas. 2012. Anxious Periods and Bank Lending. Available online: https://www.nbp.pl/badania/seminaria/4xii2012.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Dembe, A. E., and L. I. Boden. 2000. Moral hazard: A question of morality? New Solutions 10: 257–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, Asli, Edward J. Kane, and Luc Laeven. 2014. Deposit Insurance Database, NBER Working Paper Series, Working Paper 20278 July 2014. Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w20278/w20278.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Diamond, Douglas W., and Philip H. Dybvig. 1983. Bank Runs, Deposit Insurance, and Liquidity. Journal of Political Economy 91: 401–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Central Bank (ECB). 2022. Financial Stability Review, May. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/fsr/ecb.fsr202205~f207f46ea0.en.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2022).

- European Commission. 2017. Communication from the Commission: Completing the Banking Union. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/finance/docs/law/171011-communication-banking-union_en.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- European Commission. 2018. Effects Analysys (EA) on the European Deposit Incurance Scheme (EDIS). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/161011-edis-effect-analysis_en.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Fecht, Falco, Stefan Thum, and Patrick Weber. 2019. Fear, Deposit Insurance Schemes, and Deposit Reallocation in the German Banking System. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3391551 (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). 1998. A Brief History of Deposit Insurance in the United States. Available online: https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/brief/brhist.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). 2022. Bank Failures in Brief—Summary 2001 through 2022. Available online: https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/bank/ (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Garcia, Gillian. 1999. Deposit Insurance: A Survey of Actual and Best Practices, IMF Working Papers no. 99/54. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/1999/wp9954.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Garcia, Gillian. 2000. Deposit Insurance and Crisis Management, IMF Working Papers, 2000/57. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2000/wp0057.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- Garonna, Paolo, Samuele Crosetti, and Alessandra Marcelletti. 2021. Deposit Insurance in the European Union: In Search of a Third Way, Working Paper Series, Luiss School of Government, SOG-WP64/2021. Available online: https://sog.luiss.it/sites/sog.luiss.it/files/WP64%20proofs%20CORRETTO3.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Gattia, Mateo, and Tommaso Oliviero. 2021. Deposit Insurance and Banks’ Deposit Rates: Evidence from the 2009 EU Policy. International Journal of Central Banking 17: 171–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorton, Gary. 1988. Banking Panics and Business Cycles. Oxford Economic Papers 40: 751–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gropp, Reint, and Jukka Vesala. 2001. Deposit Insurance and Moral Hazard: Does the Counter Factula Matter? Working Paper no. 47/2001, European Central Bank Working Paper Series. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp047.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Grundl, Helmut, Ming Dong, and Jens Gal. 2016. The Evolution of Insurer Portfolio Investment Strategies for Long-Term Investing. OECD Journal: Financial Market Trends 2016. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/investment/evolution-insurer-strategies-long-term-investing.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Hellmann, Thomas F., Kevin C. Murdock, and Joseph E. Stiglitz. 2000. Liberalization, Moral Hazard in Banking, and Prudential Regulation: Are Capital Requirements Enough? The American Economic Review 901: 147–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoelscher, David S. 2016. The Design and Implementation of Deposit Insurance Systems. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Occasional-Papers/Issues/2016/12/31/The-Design-and-Implementation-of-Deposit-Insurance-Systems-18683 (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Hoelscher, David S., Michael W. Taylor, and Ulrich H. Klueh. 2006. The Design and Implementation of Deposit Insurance Systems, Occasional Papers. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Howarth, David, and Lucia Quaglia. 2018. The Difficult Construction of a European Deposit Insurance Scheme: A step too far in Banking Union. Journal of Economic Policy Reform 21: 190–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Association of Deposit Insurers (IADI). 2010. Core Principles for Effective Deposit Insurance Systems, A Methodology for Compliance Assessment. Available online: https://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs192.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- International Association of Deposit Insurers (IADI). 2018. Deposit Insurance Fund Target Ration. Available online: https://www.iadi.org/en/assets/File/IADI_Research_Paper_Deposit_Insurance_Fund_Target_Ratio_July2018.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2022. Monetary Policy and Central Banking—Factsheet. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/Sheets/2016/08/01/16/20/Monetary-Policy-and-Central-Banking (accessed on 21 August 2022).

- Jacklin, Charles J., and Sudipto Bhattacharya. 1988. Distinguishing Panics and Information-based Bank Runs: Welfare and Policy Implications. Journal of Political Economy 96: 568–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketcha, Nicholas J., Jr. 1999. Deposit Insurance System Design and Considerations. Available online: https://www.bis.org/publ/plcy07o.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- Khundadze, Sophio. 2009. The Problem of Moral Hazard and Effects of Deposit Insurance Project. IBSU Scientific Journal 2: 89–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kotowitz, Yehuda. 1989. Moral Hazard. In Allocation, Information and Markets. The New Palgrave. Edited by John Eatwell, Murray Milgate and Peter Newman. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laeven, Luc. 2014. The Development of Local Capital Markets: Rationale and Challenges. IMF Working Papers 14/234; Washington, DC: IMF. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, Emily. 2022. Why Are Financial Markets So Volatile? Chicago Booth Review. Available online: https://www.chicagobooth.edu/review/why-are-financial-markets-so-volatile (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Levine, Ross. 1997. Financial Development and Economic Growth: Views and Agenda. Journal of Economic Literature XXXV: 688–726. [Google Scholar]

- Lumpkin, Stephen A. 2009. Regulatory Issues Related to Financial Innovation, Financial Market Trends, vol. 22009. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/finance/financial-markets/44362117.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Mauro, Paolo, Rafael Romeu, Ariel Binder, and Asad Zaman. 2013. A Modern History of Fiscal Prudence and Profligacy, IMF Working Papers, 5. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2013/wp1305.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Nolte, Jan P., and Isfandyar Z. Khan. 2017. Deposit Insurance Systems: Addressing Emerging Challenges in Funding, Investment, Risk-Based Contributions & Stress Testing. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- Obstfeld, Maurice. 1998. The Global Capital Market: Benefactor or Menace? The Journal of Economic Perspectives 12: 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palenzuela, Diego Rodriguez, and Stephane Dees. 2016. Savings and Investment Behaviour in the Euro Area, European Central Bank Occasional Paper Series, no. 167/2016. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecbop167.en.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2022).

- Pauly, Mark V. 1968. The Economics of Moral Hazard: Comment. The American Economic Review 58: 531–37. [Google Scholar]

- Paun, Valeriu Cristian, Radu Cristian Musetescu, Vladimir Mihai Topan, and Dan Constantin Danuletiu. 2019. The Impact of Financial Sector Development and Sophistication on Sustainable Economic Growth. Sustainability 11: 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettinger, Tejvan. 2019. Moral Hazard. Available online: https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/105/economics/what-is-moral-hazard/ (accessed on 13 August 2022).

- Phillippe, Karam D., Merrouche Ouarda, Soussi Moez, and Turk Rima. 2014. The Transmission of Liquidity Shocks: The Role of Internal Capital Markets and Bank Funding Strategies, IMF Working Paper No. 2014/207. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/The-Transmission-of-Liquidity-Shocks-The-Role-of-Internal-Capital-Markets-and-Bank-Funding-42457 (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Popescu, Adina. 2022. Cross-Border Central, Bank Digital Currencies, Bank Runs and Capital, Flows Volatility, International Monetary Fund Working Papers, WO22/83. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2022/05/06/Cross-Border-Central-Bank-Digital-Currencies-Bank-Runs-and-Capital-Flows-Volatility-517625 (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Popov, Alexander. 2017. Evidence on Finance and Economic Growth, European Central Bank, Working Paper Series no. 2115/November 2017. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecb.wp2115.en.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- Salama, Bruno Meyerhof, and Vicente P. Braga. 2021. The case for private administration of deposit guarantee schemes. Journal of Banking Regulation. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schich, Sebastian. 2008. Financial Turbulence: Some Lessons Regarding Deposit Insurance, Financial Market Trends, OEDC. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/pensions/insurance/41420525.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Sia Partners. 2022. EU-Wide Guarantees for Bank Depositors: European Deposit Insurance Scheme. Available online: https://www.sia-partners.com/en/news-and-publications/from-our-experts/eu-wide-guarantees-bank-depositors-european-deposit (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Tofan, Mihaela. 2021. The relation international taxation—International Law: Formal Strains and Jurisprudential Effect. Eastern Journal of European Studies 12: 151. Available online: https://ejes.uaic.ro/articles/EJES2021_1202_TOF.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Tofan, Mihaela, and Ionel Bostan. 2022. Some Implications of the Development of E-Commerce on EU Tax Regulations. Laws 11: 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofan, Mihalea. 2022. Tax Avoidance and European Law—Redesigning Sovereignty Through Multilateral Regulation. Abingdon: Routledge Focus Book. [Google Scholar]

- Toronto Center (TC). 2017. FinTech, RegTech and SupTech: What They Mean for Financial Supervision, Global Leadership in Financial Supervision. Available online: https://www.torontocentre.org/videos/FinTech_RegTech_and_SupTech_What_They_Mean_for_Financial_Supervision.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2017. The Role of Development Banks in Promoting Growth and Sustainable Development in the South, United Nations—New York and Geneva. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/gdsecidc2016d1_en.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).