Restorative Justice, Youth Violence, and Policing: A Review of the Evidence

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Restorative Justice, Restorative Practice, and Its Applications

‘not limited to formal processes, such as restorative conferences or family group conferences, but range from informal to formal […] the informal practices include affective statements that communicate people’s feelings, as well as affective questions that cause people to reflect on how their behavior has affected others. […] As restorative practices become more formal, they involve more people, require more planning and time, and are more structured and complete.’

- Direct contact (face-to-face): for example, victim-offender conferences, circles;

- Indirect contact (non-face-to-face): for example, letter writing, shuttle work;

- Potentially overlapping processes: for example, victim and offender circles that may or may not intersect, surrogate offender interactions;

- Discrete processes: for example, healing circles for victims, community or family to repair relationships.

1.2. Policing, Young People, Violence, and Restorative Justice

1.3. Context for the Study

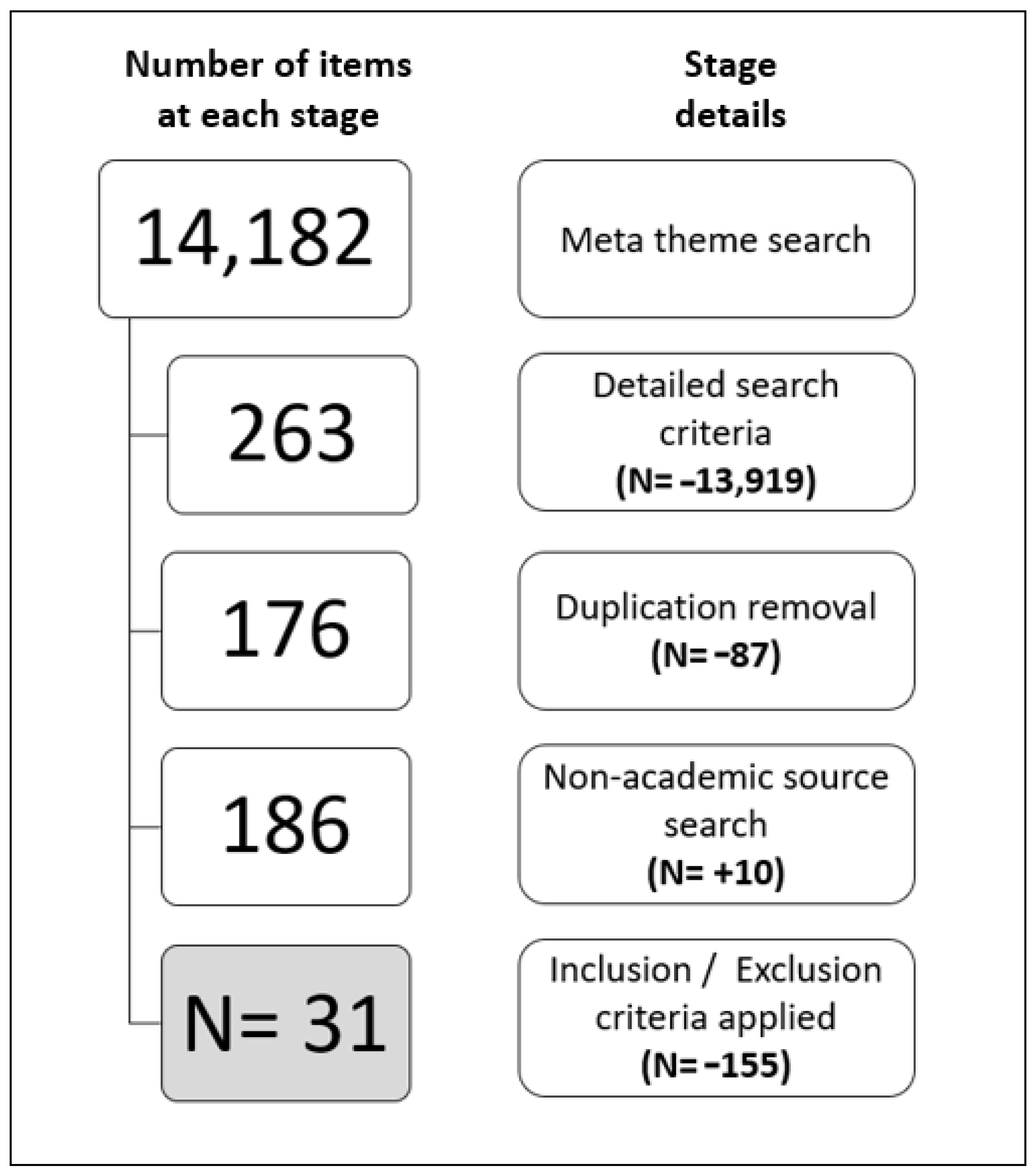

2. Method

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Academic Database Searching Approach

2.3. Non-Academic Database Searching Approach

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Sifting Process

- Reporting empirical research, policy analysis or reflection, restorative justice intervention evaluations, applied research, and exploratory research (D). Papers could be qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods (R). Opinion pieces, personal blogs, reviews of literature, and descriptive papers with no empirical component or reflective pieces were excluded.

- Centred on an intervention aimed at reducing youth violence or improving victim outcomes (D). Reviewed studies included the varied experiences in the implementation and development process in both criminal and non-criminal justice settings (such as schools).

- Describing any restorative justice technique/approach; the search was not confined by a narrow understanding of restorative justice limited to face-to-face conferencing/interventions (PI).

- Nature of the intervention

- Target population?

- Intervention?

- Location?

- What was found to work well?

- What problems were identified?

- What potential solutions were identified?

2.5. Quality Evaluation

3. Results

3.1. Included Studies

3.2. Details of the Studies Included

4. Discussion

4.1. Benefits

4.2. Challenges

4.3. Delivery Considerations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ali Al-Hassani, Ruba. 2021. Storytelling: Restorative Approaches to Post-2003 Iraq peacebuilding. Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 15: 510–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- All Party Parliamentary Group for Restorative Justice. 2021. Restorative Justice APPG Inquiry into Restorative Practices in 2021/2022: Report on the Inquiry into Restorative Practices in 2021/2022. Other. London: All Party Parliamentary Group on Restorative Practices. [Google Scholar]

- Angel, Caroline. 2005. Victims Meet Their Offenders: Testing the Impact of Restorative Justice Conferences on Victims’ Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, Lisa Mary. 2021. Is restorative justice an effective approach in responding to children and young people who sexually harm? Laws 10: 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, Cynidi. 2011. Protecting the rights of the child: Regulating restorative justice and indigenous practices in Southern Sudan and East Timor. The International Journal of Children’s Rights 19: 167–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banwell-Moore, Rebecca. 2019. Restorative Justice: Understanding the Enablers and Barriers to Victim Participation in England and Wales. Ph.D. thesis, The University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Banwell-Moore, Rebecca. 2022. Just an ‘optional extra’ in the ‘victim toolkit’?: The culture, mechanisms and approaches of criminal justice organisations delivering restorative justice in England and Wales. International Review of Victimology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barretto, Craig, Sarah Miers, and Ian Lambie. 2018. The views of the public on youth offenders and the New Zealand criminal justice system. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 62: 129–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackley, Riddhi, and Lorana Bartels. 2018. Sentencing and Treatment of Juvenile sex Offenders in Australia. Woden: Australian Institute of Criminology. [Google Scholar]

- Bonell, Chris, Elizabeth Allen, Emily Warren, Jennifer McGowan, Leonardo Bevilacqua, Farah Jamal, Rosa Legood, Meg Wiggins, Charles Opondo, Anne Mathiot, and et al. 2018. Effects of the Learning Together intervention on bullying and aggression in English secondary schools (INCLUSIVE): A cluster randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 392: 2452–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, John. 1989. Crime, Shame, and Reintegration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brathay Trust. 2017. Turning the Spotlight Evaluation Report. Turning the Spotlight Perpetrator Programme. Available online: https://restorativethinking.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/The-Brathay-Trust-Turning-the-Spotlight-Evaluation-Report-final-Sept-2017-2.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Calkin, Charlotte. 2021. An explanatory study of understandings and experiences of implementing restorative practice in three UK prisons. British Journal of Community Justice 17: 92–111. [Google Scholar]

- Clamp, Kerry, and David O’Mahony. 2019. Restorative policing provision across England and Wales in 2018. Nottingham: University of Nottingham. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Janine Natalya. 2012. Youth violence in South Africa: The case for a restorative justice response. Contemporary Justice Review 15: 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, Andy, Gerrard Drennan, and Margie Callanan. 2015. A qualitative exploration of the experience of restorative approaches in a forensic mental health setting. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology 26: 510–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, Alison, Debbie Smith, and Andrew Booth. 2012. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research 22: 1435–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossins, Annie. 2008. Restorative justice and child sex offences: The theory and the practice. The British Journal of Criminology 48: 359–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criminal Justice Joint Inspection. 2012. Facing Up to Offending: Use of Restorative Justice in the Criminal Justice System. Available online: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/media/facing-up-to-offending-20120918.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Daly, Kath. 2006. Restorative justice and sexual assault. British Journal of Criminology 46: 334–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhami, Mandeep K., Greg Mantle, and Darrell Fox. 2009. Restorative justice in prisons. Contemporary Justice Review 12: 433–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzur, Albert, and Susan Olson. 2004. The Value of Community Participation in Restorative Justice. Journal of Social Philosophy 35: 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, Anna. 2009. A Bottom-Up Approach to Transformative Justice in Northern Ireland. The International Journal of Transitional Justice 3: 301–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finfgeld-Connett, Deborah, and E. Dianne Johnson. 2013. Literature search strategies for conducting knowledge-building and theory-generating qualitative systematic reviews. Journal of Advanced Nursing 69: 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froggett, Lynn. 2007. Arts based learning in restorative youth justice: Embodied, moral and aesthetic. Journal of Social Work Practice 21: 347–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, Tali. 2021. Setting Standards for Child-Inclusive Restorative Justice. Family Court Review 59: 144–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldson, Barry. 2011. The Independent Commission on Youth Crime and Antisocial Behaviour: Fresh start or false dawn? Journal of Children’s Services 6: 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hand, Carol A., Judith Hankes, and Tony House. 2012. Restorative justice: The indigenous justice system. Contemporary Justice Review 15: 449–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harden, Troy, Thomas Kenemore, Karen Mann, Michael Edwards, Christine List, and Karen Jean Martinson. 2015. The truth n’trauma project: Addressing community violence through a youth-led, trauma-informed and restorative framework. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 32: 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, Ken. 2011. Violent youth culture in Northern Ireland: Young men, violence, and the challenges of peacebuilding. Youth and Society 43: 414–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, Jonathan, Brian Payne, Kenneth Lynch, and Darren Hyde. 2021. Restorative practices in institutional settings: The challenges of contractualised support within the managed community of supported housing. Laws 10: 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, Carolyn, and Fernanda Fonseca Rosenblatt. 2016. Looking back to the future: Threats to the success of restorative justice in the United Kingdom. Victims & Offenders 11: 30–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, Don R. 2017. Predicting Violent Incidence and Disciplinary Actions in Schools: Use of the National Center for Educational Statistics to Examine School Violence Interventions. Ph.D. thesis, University of Texas Arlington, Arlington, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hee Joo, and Jurg Gerber. 2012. The effectiveness of reintegrative shaming and restorative justice conferences: Focusing on juvenile offenders’ perceptions in Australian reintegrative shaming experiments. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 56: 1063–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkwood, Steve, and Rania Hamad. 2019. Restorative justice informed criminal justice social work and probation services. Probation Journal 66: 398–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koss, Mary. 2014. The RESTORE Program of Restorative Justice for Sex Crimes: Vision, Process and Outcomes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 29: 1623–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, Jodi, Susan Turner, Terry Fain, and Amber Sehgal. 2007. The effects of an experimental intensive juvenile probation program on self-reported delinquency and drug use. Journal of Experimental Criminology 3: 201–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London Assembly Police and Crime Committee. 2016. Serious Youth Crime Report. Available online: https://www.london.gov.uk/about-us/london-assembly/london-assembly-publications/serious-youth-violence (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Mann, Jacqueline M. 2016. Peer Jury: School Discipline Administrators’ Perceptions of a Restorative Alternative to Suspension and Expulsion. Ph.D. thesis, Hampton University, Hampton, VA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Marder, Ian D. 2020a. Institutionalising restorative justice in the police: Key findings from a study of two English police forces. Contemporary Justice Review 23: 500–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marder, Ian D. 2020b. The new international restorative justice framework. The effects of an experimental intensive juvenile probation program on self-reported delinquency and drug use: Reviewing three years of progress and efforts to promote access to services and cultural change. The International Journal of Restorative Justice 3: 395–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateer, Susan C. 2010. The Use of Restorative Justice Practices in a School Community Traumatized by an Incident of Planned School Violence: A Case Study. Ph.D. Thesis, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA. [Google Scholar]

- McAra, Lesley, and Susan McVie. 2010. Youth crime and justice: Key messages from the Edinburgh study of youth transitions and crime. Criminology and Criminal Justice 10: 179–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Justice/Youth Justice Board. 2018. Referral Order Guidance. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/746365/referral-order-guidance-9-october-2018.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Morse, Janice M., Michael Barrett, Maria Mayan, Karin Olson, and Jude Spiers. 2002. Verification Strategies for Establishing Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 1: 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movsisyan, Armine. 2014. Students’ Perceptions of School Interventions to Reduce Violence. Ph.D. thesis, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Moyer, Jeffrey S., Mark R. Warren, and Andrew R. King. 2020. “Our Stories Are Powerful”: The Use of Youth Storytelling in Policy Advocacy to Combat the School-to-Prison Pipeline. Harvard Educational Review 90: 172–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, Ana M., Joana Andrade, and Andreia de Castro Rodrigues. 2022. The Psychological Impact of Restorative Justice Practices on Victims of Crimes—A Systematic Review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahoney, David, and Jonathan Doak. 2017. Reimagining Restorative Justice: Agency and Accountability in the Criminal Process. Oxford: Hart Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ohmer, Mary L., Barbara D. Warner, and Elizabeth Beck. 2010. Preventing violence in low-income communities: Facilitating residents’ ability to intervene in neighborhood problems. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare 37: 161. [Google Scholar]

- Pali, Brunilda, and Giuseppe Maglione. 2021. Discursive representations of restorative justice in international policies. European Journal of Criminology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, Kate, Sarah Pollock, and Deanna Edwards. 2018. Family Group Conferences: An Opportunity to Re-Frame Responses to the Abuse of Older People? The British Journal of Social Work 48: 1109–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, Allison, and Kelly Welch. 2018. The effect of school conditions on the use of restorative justice in schools. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 16: 224–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, Biran, Jonathan Hobson, and Kenneth Lynch. 2021. ‘We just want to be treated with respect!’: Using restorative approaches and the dramatic arts to build positive relationships between the police and young people. Youth Justice 21: 255–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peurača, Branka, and Lucija Vejmelka. 2015. Nonviolent Conflict Resolution in Peer Interactions: Croatian Experience of Peer Mediation in Schools. Social Work Review/Revista De Asistenta Sociala 14: 123–43. [Google Scholar]

- Roach, Kent. 2013. The institutionalization of restorative justice in Canada: Effective reform or limited and limiting add-on? In Institutionalizing Restorative Justice. Vancouver: Willan, pp. 187–213. [Google Scholar]

- Roche, Declan. 2006. Dimensions of restorative justice. Journal of Social Issues 62: 217–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, Fernanda Fonseca. 2014. Community involvement in restorative justice: Lessons from an English and Welsh case study on youth offender panels. Restorative Justice: An International Journal 2: 280–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossner, Meredith. 2017. Restorative justice and victims of crime: Directions and developments. In Handbook of Victims and Victimology. Edited by Sandra Walklate. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, Samantha, Melanie Baak, Garth Stahl, and Ben Adams. 2021. Restorative practices for preventing/countering violent extremism: An affective-discursive examination of extreme emotional incidents. British Journal of Sociology of Education 42: 1227–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapland, Joanna, Adam Crawford, Emily Gray, and Daniel Burn. 2017. Restorative Justice at the Level of the Police in England: Implementing Change. Occasional Paper 8. Sheffield: Centre for Criminological Research, The University of Sheffield. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, Lawrence, and Heather Strang. 2007. Restorative Justice: The Evidence. London: Smith Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Smokowski, Paul. R., Martica Bacallao, Caroline B. Evans, Roderick A. Rose, Katie C. Stalker, Shenyang Guo, Qi Wu, James Barbee, and Meredith Bower. 2018. The North Carolina Youth Violence Prevention Center: Using a multifaceted, ecological approach to reduce youth violence in impoverished, rural areas. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research 9: 575–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The 2018 Council of Europe Recommendation CM/Rec. 2018. Concerning Restorative Justice in Criminal Matters. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/prison/home/-/asset_publisher/ky2olXXXogcx/content/recommendation-cm-rec-2018-8 (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- The Independent Commission on Youth Crime and Antisocial Behaviour. 2010. Time for a Fresh Start: The Report of the Independent Commission on Youth Crime and Antisocial Behaviour. Available online: www.police-foundation.org.uk/youthcrimecommission/images/076_freshstart.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- US Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services. 2016. Combatting Youth Violence in American Cities. Available online: https://cops.usdoj.gov/RIC/Publications/cops-w0806-pub.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Utheim, Ragnhild. 2011. Reclaiming the Collective: Restorative Justice, Structural Violence, and the Search for Democratic Identity under Global Capitalism. Ph.D. thesis, City University of New York, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Van Camp, Tinneke, and Jo-Anne Wemmers. 2013. Victim satisfaction with restorative justice: More than simply procedural justice. International Review of Victimology 19: 117–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varker, Tracey, David Forbes, Lisa Dell, Adele Weston, Tracy Merlin, Stephanie Hodson, and Meaghan O’Donnell. 2015. Rapid evidence assessment: Increasing the transparency of an emerging methodology. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 21: 1199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wachtel, Ted. 2016. Defining Restorative. International Institute for Restorative Practices. Available online: https://www.iirp.edu/restorative-practices/defining-restorative/ (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Wallis, Pete, Leeann McLellan, Kathryn Clothier, and Jenny Malpass. 2013. The Assault Awareness Course and New Drivers’ Initiative; Groupwork programmes for young people convicted of violent and vehicle offences. Groupwork 23: 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youth Select Committee. 2019. Our Generation’s Epidemic: Knife Crime. Available online: https://www.byc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Youth-Select-Committee-Our-Generations-Epedemic-Knife-Crime.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Zhang, Yan, and Yiwei Xia. 2021. Can Restorative Justice Reduce Incarceration? A Story From China. Justice Quarterly 38: 1471–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehr, Howard. 1990. Changing Lenses: A New Focus for Crime and Justice. Scottdale: Herald Press. [Google Scholar]

| Author(s) | Location | Focus of Study | Findings Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Armstrong (2021) | Scotland | An analysis of prior work exploring the reasons why a restorative approach may be of benefit give the perceived failure of conventional criminal justice in addressing the growing problem of child and adolescent harmful sexual behaviour (HSB) in Scotland. | Restorative approaches may be warranted given the perceived failure of conventional criminal justice in addressing child and adolescent HSB in Scotland. Such approaches can empower victims and offer them the opportunity to seek answers to the questions the CJS cannot provide. |

| Banks (2011) | Southern Sudan and East Timor | Comparative examination of draft laws in Southern Sudan and East Timor to provide insights into policy choices and the relationship between international norms of child protection and traditional restorative practices. | The importance of considering the relationship between international norms of child protection and traditional and cultural restorative practices. |

| Barretto et al. (2018) | New Zealand | A qualitative analysis of an open-ended survey from a nationally representative sample on public sentiments to address youth justice issues. | Public sentiments showed considerable support for a multi-faceted approach that utilised a combination of rehabilitative, punitive, and restorative forms of justice. |

| Blackley and Bartels (2018) | Australia | Examination of sentencing and treatment practices for juvenile sex offenders in Australia, using examples of judicial reasoning in sentencing. | Multi-systems and ecological approaches to treatment that promote offender rehabilitation and accountability while also providing justice and safety for victims and communities. These included restorative justice conferencing and therapeutic treatment orders, which showed promising results in reducing sexual recidivism. |

| Bonell et al. (2018) | England | Cluster randomised trial, with economic and process evaluations, of the Learning Together intervention compared with standard practice (controls) over 3 years in secondary schools in south-east England. | Learning Together consisted of staff training in restorative practice; convening and facilitating a school action group; and a student social and emotional skills curriculum. Primary outcomes were self-reported experience of bullying victimisation (Gatehouse Bullying Scale) and perpetration of aggression (Edinburgh Study of Youth Transitions and Crime School Misbehaviour Subscale) measured at 36 months. Data was analysed using intention-to-treat longitudinal mixed-effects models. |

| Brathay Trust (2017) | England | Analysis of the Turning the Spotlight Programme led by Cumbria Office for the Police Crime Commissioner and delivering programmes to prevent and reduce incidents of hate crime and domestic abuse. | High numbers of participants from the programmes reported an increased sense of empowerment in relation to keeping themselves safe, including personal development factors such as: increased feelings of self-worth, improved communication skills, increased awareness of self and situational context, and recognition of personal strengths. |

| Clark (2012) | South Africa | Examination of the potential merits of restorative justice as a response to the problem of youth violence, focusing particularly on the 2009 Child Justice Act based on fieldwork in South Africa. | This research draws on both the author’s qualitative interview data and a range of surveys with young people conducted by the Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention in Cape Town. |

| Cossins (2008) | Australia, the United Kingdom, and New Zealand | Re-analysis of the data reported in Daly (2006) (see below) and comparing restorative justice with other reforms to sexual assault trials. The research looked to explore whether restorative justice is one of the ways forward in the difficult area of prosecuting child sex offenses. | There is insufficient evidence to support the view that there are inherent benefits in the restorative justice process that provide victims of sexual assault with a superior form of justice. The major concern is that restorative justice will not be able to defuse the power relationship between victim and offender and will re-traumatize victims. |

| Criminal Justice Joint Inspection (2012) | England and Wales | Joint Inspection by HM Inspectorate of Constabulary, HM Inspectorate of Probation, HM Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate, and HM Inspectorate of Prisons. Fieldwork comprised an inspection of police forces, probation trusts, and youth offending teams (YOTs) in six areas: Sussex, Norfolk, Merseyside, West Midlands, Greater Manchester, and North Wales. In each area the researchers interviewed staff, victims, and offenders; conducted focus groups with the public; examined a sample of case records, and; inspected custodial establishments. | Over three-quarters of victims participating directly in youth offender panels were happy with their experience of restorative justice and said that it was effective in achieving reparation for the harm done to them. However, not enough victims are engaging directly with youth offender panels. |

| Daly (2006) | Australia | Drawing on the South Australia Juvenile Justice project dataset to analyse youth peer violence (‘punch-ups’) with a focus on girl-on-girl assaults. | Debate on the appropriateness of RJ for cases of gendered violence is polarized, in part, because there is a lack of empirical evidence and, in part, because of the symbolic politics of justice in responding to violence against women and child victims. However, the conference process was found to be less victimizing than the court process and may produce more effective outcomes. |

| Daly (2006) | Australia | Findings from an archival study of nearly 400 cases of youth sexual assault, comparing conference cases to community service cases over a six-and-a-half-year period. | For conference cases, participation in the Mary Street Programme (RJ) was associated with the lowest prevalence of reoffending (43 per cent), and community service was associated with higher levels (56 per cent). |

| Froggett (2007) | England | Analysis of video data from a creative writing project with young offenders in the context of individuated restorative justice programmes. | It was found that a crucial step in moral learning for these young people is the willingness to self-reflectively acknowledge their own destructiveness in a context which fosters an internal sense of guilt and concern for the hurt caused to others. |

| Gal (2021) | International | Review of existing findings from the fields of RJ, children’s rights, psychology, and victimology. | A positive RJ process can provide a constitutive event for children that can affect the way they develop, can strengthen and even repair support systems, enhance resilience, and reduce use of maladaptive coping mechanisms such as self-blame and aggression. |

| Harden et al. (2015) | USA | Analysis of a youth violence prevention and intervention program involving 44 high school-age youth from violence-exposed urban communities in a nine-month, multidisciplinary, after-school program. | Youth in the communities experienced pervasive traumatic stress and in multiple manifestation, and the evaluated the programme showed statistically significant pre- and post-test differences in mean scores for participants on 41 outcome measures (for school, community, family, experience, and self) as compared to just 4 statistically significant pre- and post-test differences in mean scores for the comparison group for measures of community and self. |

| Harland (2011) | Northern Ireland | Qualitative study carried out by the Centre for Young Men’s Studies with 130 marginalized young men aged 13 to 16 from 20 different communities across Northern Ireland addressing themes of violence, conflict, and safety. | Multi agency approaches with local community-led programs and peacebuilding processes can help to engage marginalized young men in peacebuilding, better prepare them for living in a multicultural society, and help alleviate the fear, apprehension, suspicion, and distrust of others. |

| Kelly (2017) | USA | Data from National Centre for Educational Statistics study of US schools (n = 2648), used to identify use of interventions intended to reduce school violence. | Identified interventions intended to reduce school violence. Schools that used Conflict Transformation Education interventions and Restorative Justice/Discipline interventions were predictive of lower rates of violence reported in schools. Schools which reported using both mental health and restorative justice/discipline together reported lower rates of disciplinary actions. |

| Kim and Gerber (2012) | Australia | Australian data from Reintegrative Shaming Experiments between 1995 and 1999 examining juvenile offenders’ perceptions on preventing reoffending, repaying the victim and society, and the degree of repentance. | There was no significant relationship between RJ conference and the offenders’ own perceptions on the prevention of future offending. However, those who experienced RJ conferences are significantly more likely to perceive that they were able to repay the victim and repay society than those who had experienced traditional court processing. |

| Lane et al. (2007) | USA | Randomized experiment, comparing youths in the experimental group, who had interventions that were restorative, with those on routine probation, using interviews with youths in both the experimental and control groups 1 year after random assignment. | Youths who had the restorative treatment were less likely to have taken drugs recently and less likely to have been involved in violence or homicide. |

| London Assembly Police and Crime Committee (2016) | England | London Assembly Police and Crime Committee report on causes of youth serious crime and how best to prevent offending | Approaches to tackling serious youth violence should include RJ, which would build London’s focus on young victims. |

| Mann (2016) | USA | Examination of the perceptions of school discipline administrators on implementing Peer Jury as an alternative school discipline strategy. Analysed the impact on attendance, instruction, recidivism of negative behaviour, and the disproportionality in the issuance of sanctions. | Peer Jury approaches in schools: (1) promotes leadership, accountability, ownership, and civic engagement; (2) increases student attendance and instructional time; (3) decreases discipline problems and negative behaviour, including recidivism rates; (4) are recommended as an alternative to suspension and expulsion; (5) can support parents and community engagement; (7) addresses disproportionality of sanctions issued; (8) are an effective discipline option. |

| Mateer (2010) | USA | Using a case study format with interviews of involved administrators, teachers, and juvenile justice practitioners to document how a junior high school community recovered from a planned copycat to the Columbine shooting. | Restorative justice practices used in the school were uniquely suited to the event and responsive to the healing needs of the community at the time. In this situation not only was the harm repaired, but the community used the pain created by the harm to create a transformation improving the school. |

| Movsisyan (2014) | USA | A qualitative case study which included interviews of students from grade 9–12 who had experience with school violence and with the assistant principal. | Youths at the school felt that the use of restorative justice and other similar communication approaches helped them to feel safe and not fear violence at school. The youths stated that because they felt safer, they were less prone to engage in violence to defend themselves. |

| Moyer et al. (2020) | USA | Qualitative interviews and observations used to construct a case study of the successful campaign by Voices of Youth in Chicago Education to pass SB100, a progressive Illinois law aimed at ending the school-to-prison pipeline. | Storytelling empowered young people, particularly historically marginalised groups, and strengthened their relationships within the campaign, enabling them to see that their experiences were shared by others and therefore part of a larger systemic problem. |

| Ohmer et al. (2010) | USA | Description of an exploratory study of a pilot training program the authors developed to facilitate residents’ ability to intervene in neighbourhood problems in a low-income community in Atlanta, Georgia. | After the programme trial, willingness to use direct intervention in problem situations increased from 3 to 9 out of 10. Restorative practices equipping people with skills to approach a situation with peaceful and non-threatening strategies and gave confidence to tackle conflicts more directly. |

| Payne and Welch (2018) | USA | Analysis of data from a nationally representative sample of schools to examine school conditions that influence the use of restorative responses to violence and misbehaviour. | Restorative justice consistently produced positive effects, regardless of school characteristics. If implemented more broadly within schools, restorative justice may substantially reduce student offending, increase perceptions of safety, enhance learning, promote positive school climate, and dismantle the school-to-prison pipeline that is exacerbating inequality and disadvantage for certain students. |

| Peurača and Vejmelka (2015) | Croatia | Analysis of a peer mediation programme based on interviews with three experienced experts in the field of peer mediation in Croatian schools. | The study found that there is the need to work on improving the implementation of peer mediation in schools, through: Innovative and comprehensive promotion of peer mediation; quality education of children and adults in peer mediation; evidence-based practice; multidisciplinary and cross-sectional cooperation; well planned and systematic collection of data and availability of results; systematic evaluation of programmes. |

| Smokowski et al. (2018) | USA | Analysis of the North Caroline Youth Violence Prevention Center programme including ‘Positive Action’, administered in 13 middle schools for 3 years; ‘Parenting Wisely’, an online program provided to 300 parents; ‘Teen Court’, a community-based restorative justice alternative provided to 400 adolescents; and additional county-level data on levels of youth violence. | The efforts of this university–community partnership was associated with a 47% reduction in non-school-based offenses, a 31% reduction in undisciplined/delinquent complaints, and an 81% reduction in the use of corporal punishment, along with smaller reductions in school-based offenses, short-term suspensions, and assaults. In addition, some county-level indicators of violence decreased. |

| The Independent Commission on Youth Crime and Antisocial Behaviour (2010) | England, Wales, Northern Ireland | Inquiry prompted by concern about deep-rooted failings in the response to antisocial behaviour and crime involving children and young people | The Commission proposed a major expansion of restorative justice in England and Wale to include youth conferencing as the centerpiece of responses to all, but the most serious offences committed by children and young people. |

| US Department of Justice (2016) | USA | Descriptions of approaches taken to combat youth violence submitted by mayors and other officials in 30 US cities of varying sizes and representing every region of the country. | A successful response calls for strong partnerships between mayors and police chiefs of the kind that community restorative policing concepts have been shown over the past two decades to strengthen. |

| Utheim (2011) | USA | Examination of the use of restorative practices for navigating conflicts among court-involved youth at an urban high school. | A restorative ethos allows social actors the opportunity to reclaim their human agency as participants of social conflicts. The sense of communal belonging and common humanity that restorative processes aim to inspire was often captured in conversations with senior or former students. |

| Wallis et al. (2013) | England | Analysis of a Youth Offending Service innovative groupwork programmes, one for young people who have committed violent offences and the other for car crimes. | The young people that undertook the course saw value, and very few came back to the attention of the YOS for similar offences. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hobson, J.; Twyman-Ghoshal, A.; Banwell-Moore, R.; Ash, D.P. Restorative Justice, Youth Violence, and Policing: A Review of the Evidence. Laws 2022, 11, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws11040062

Hobson J, Twyman-Ghoshal A, Banwell-Moore R, Ash DP. Restorative Justice, Youth Violence, and Policing: A Review of the Evidence. Laws. 2022; 11(4):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws11040062

Chicago/Turabian StyleHobson, Jonathan, Anamika Twyman-Ghoshal, Rebecca Banwell-Moore, and Daniel P Ash. 2022. "Restorative Justice, Youth Violence, and Policing: A Review of the Evidence" Laws 11, no. 4: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws11040062

APA StyleHobson, J., Twyman-Ghoshal, A., Banwell-Moore, R., & Ash, D. P. (2022). Restorative Justice, Youth Violence, and Policing: A Review of the Evidence. Laws, 11(4), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws11040062