Electronic Surveillance in Court Proceedings and in the Execution of Criminal Penalties: Legislative and Logistical Steps Regarding Operationalising the Electronic Monitoring Information System (EMIS) in Romania

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. EM of Individuals under Sanctions Imposed by the Justice System. Main Principles and Applicable Rules

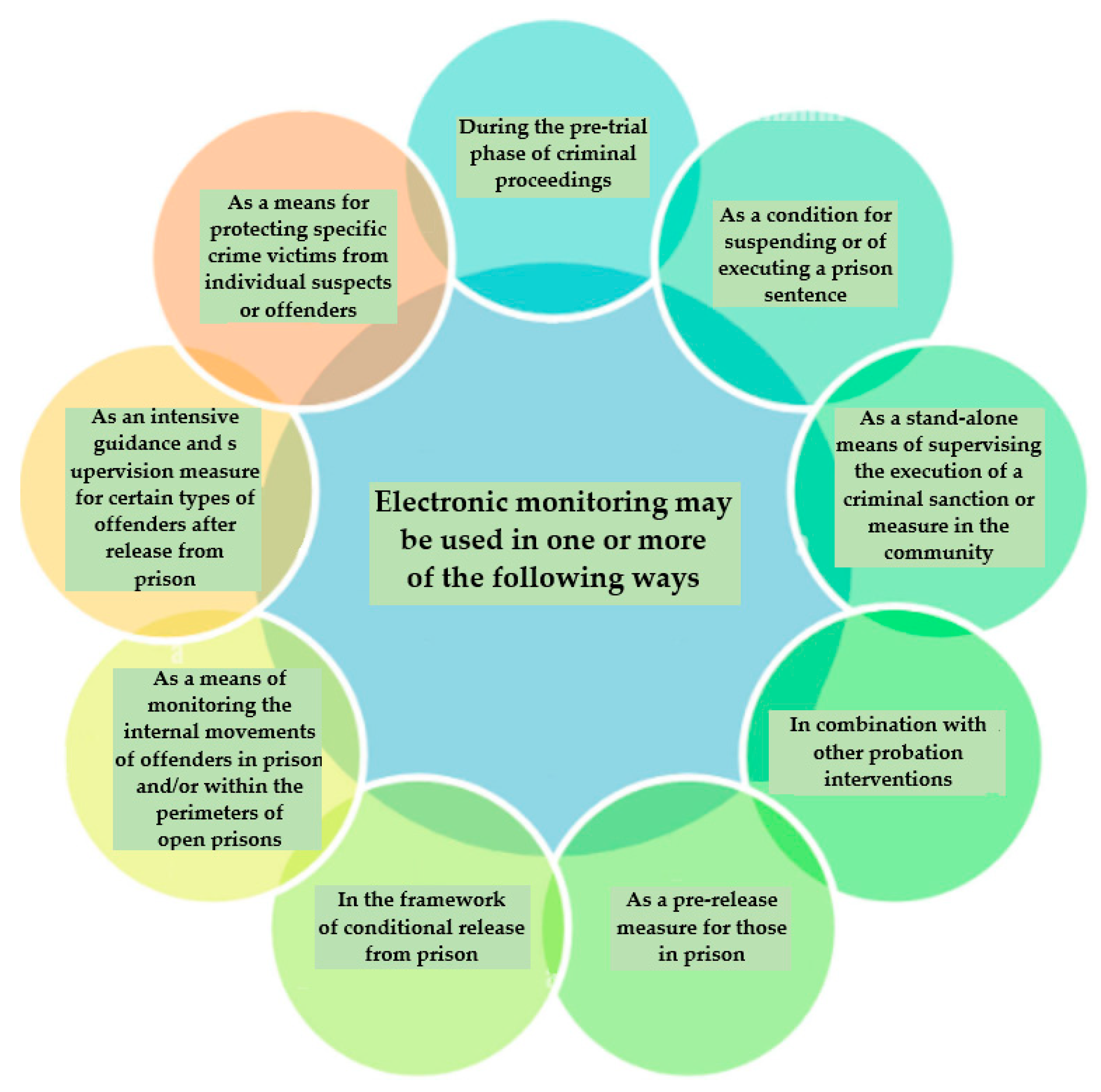

3.1. The Requirements Applicable for Introducing the EM of Individuals Undergoing Criminal Justice Derived from the Recommendation of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe (No. 004/2014)

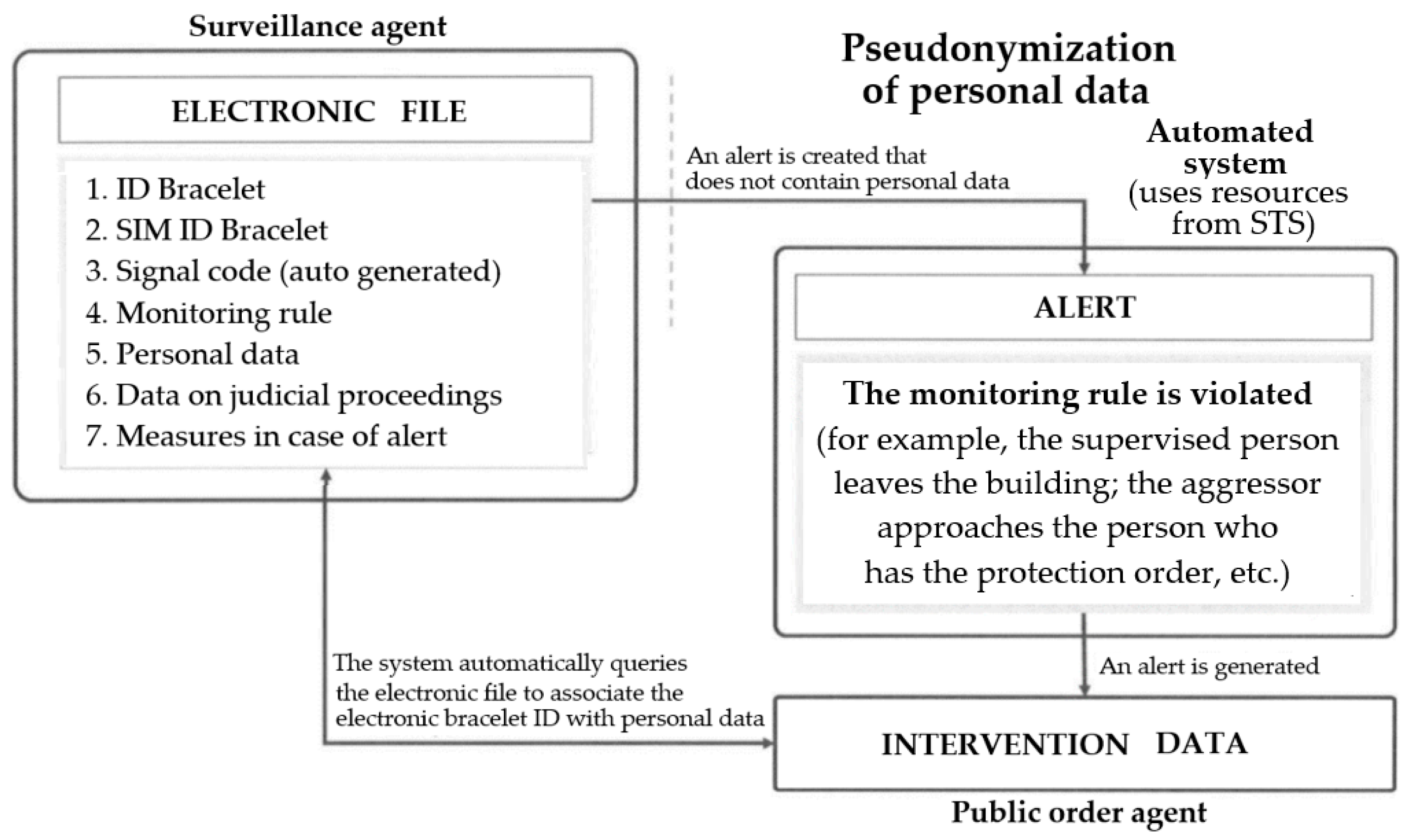

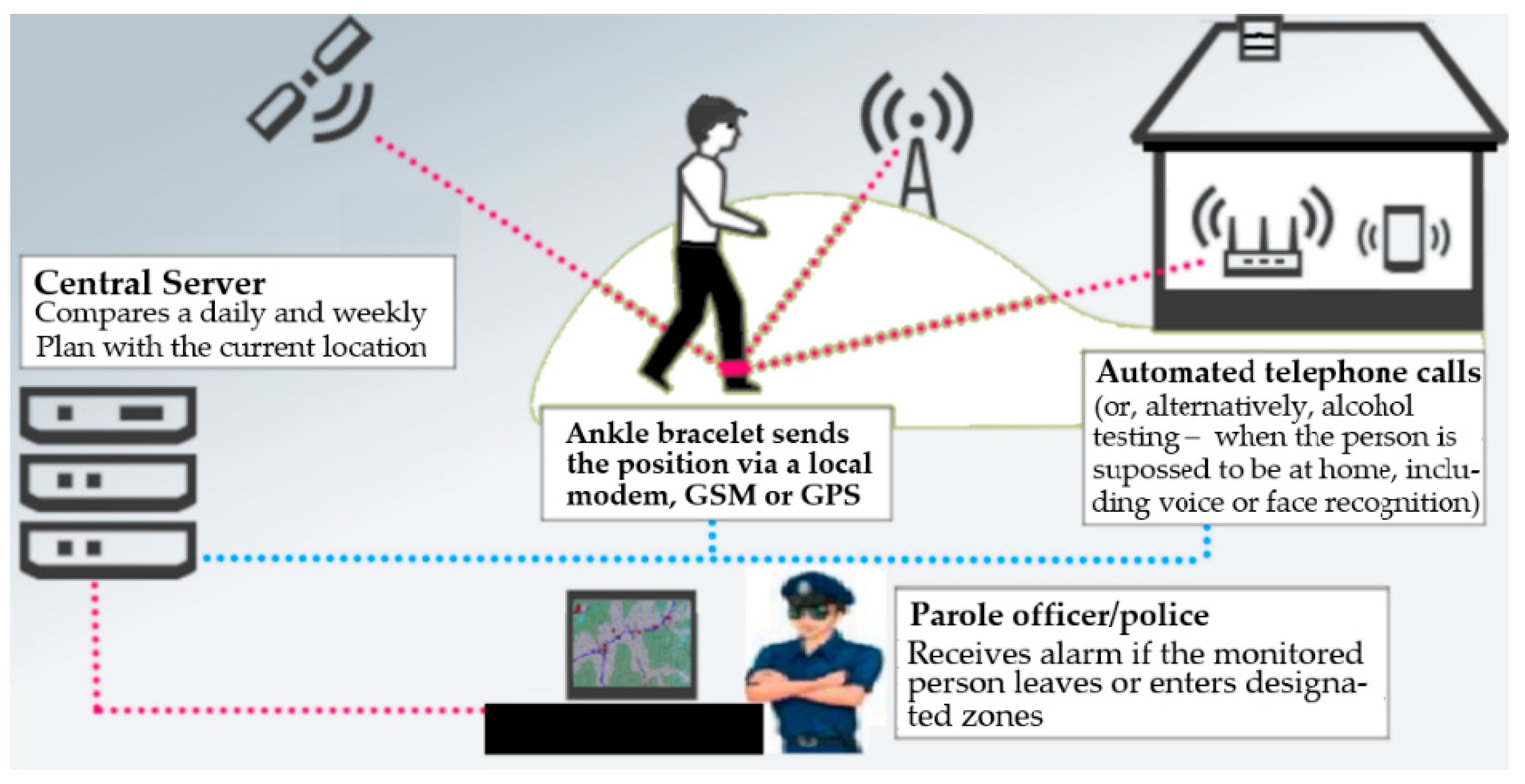

3.2. The General Principle of EM System Operation of Individuals under Restrictions Imposed by the Justice Systems

4. Attempts to Establish EM of Individuals under Sanctions during Criminal Justice Proceedings in Romania

4.1. First Rules Providing for the Introduction of EM into Romanian Criminal Law

4.2. Adoption of a Special Law on EM during Criminal Justice Proceedings and in Sentence Execution

4.2.1. Motivations for Supporting a Law on EM during Judicial Proceedings and Sentence Execution

4.2.2. Binding Provisions Included in the New Legislative Regulation

4.3. Implications of the Law on EM on the Content of Other Regulatory Acts

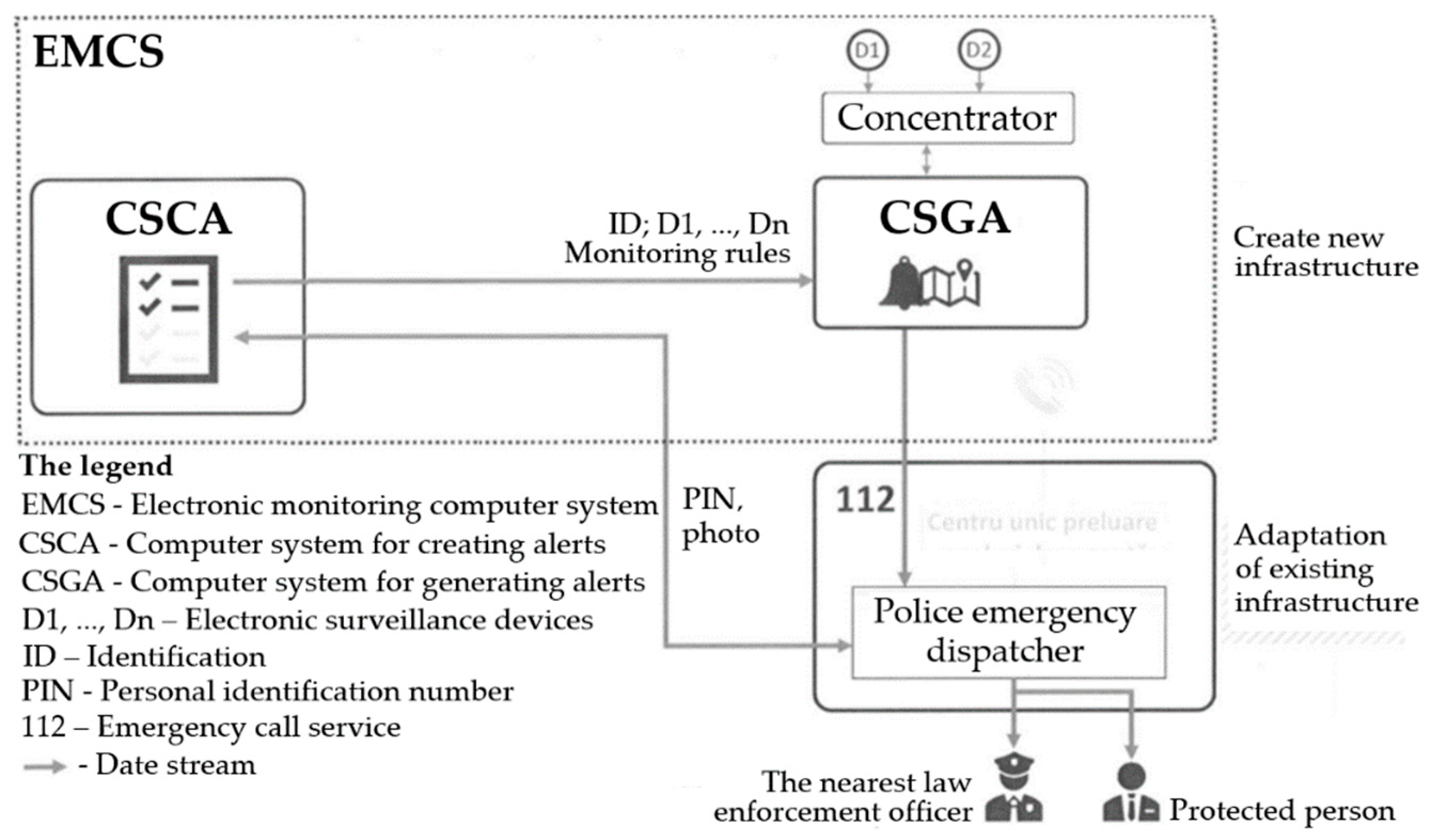

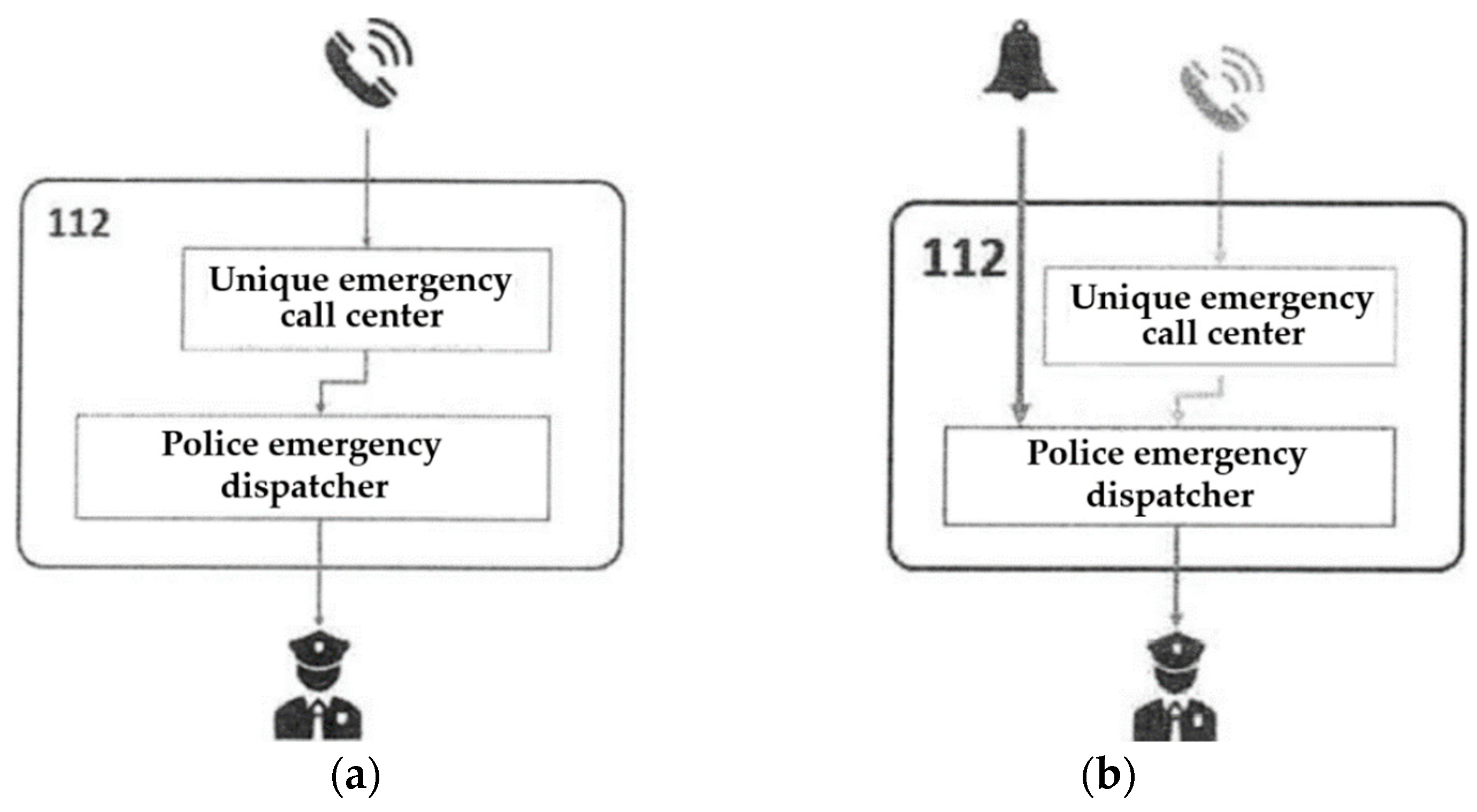

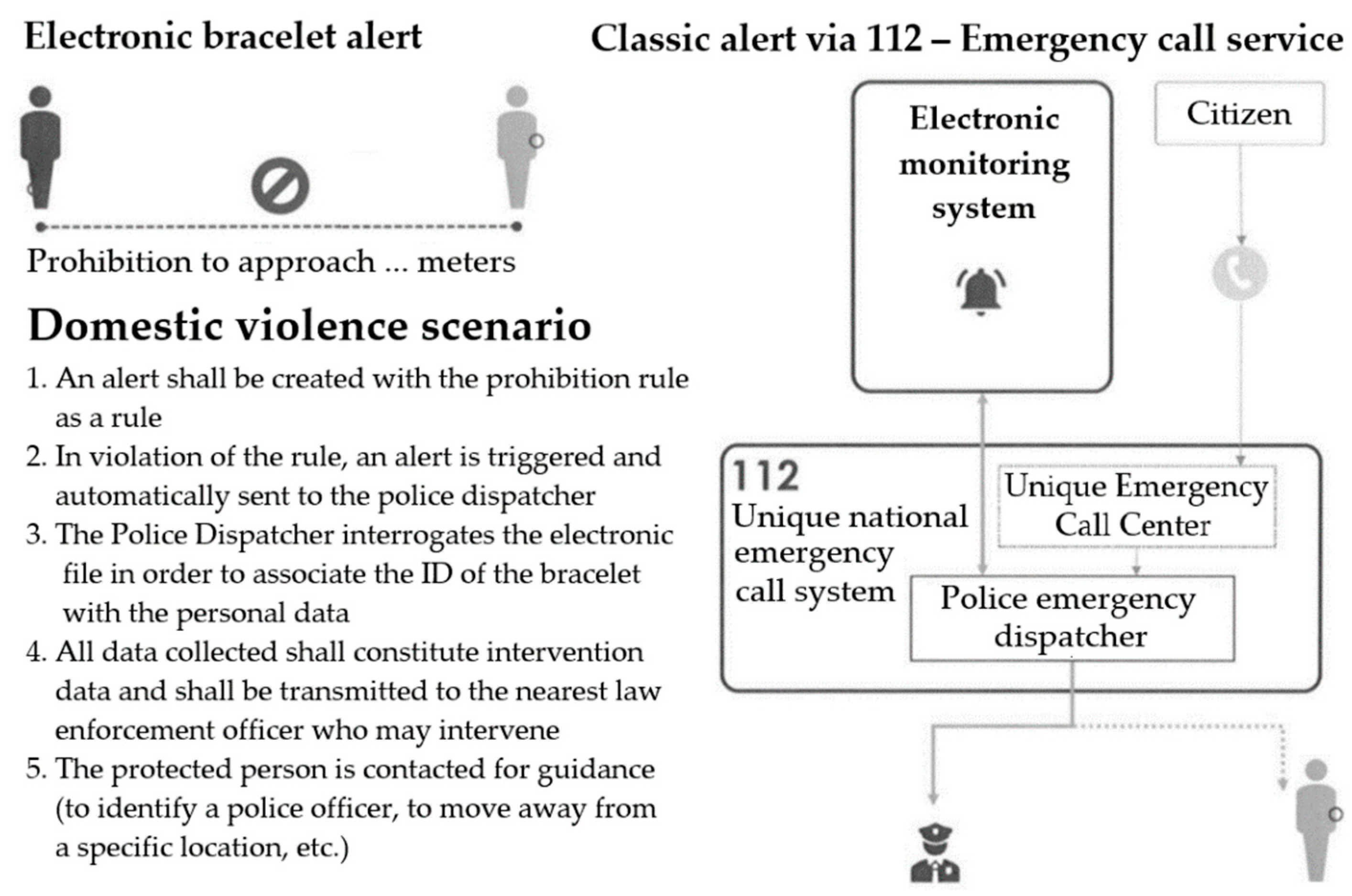

4.4. Technical and Organisational Aspects Regarding the Operationalisation of the EMIS Pilot System

- I (2022–2023)—in the capital and three other counties (Iași, Mureș and Vrancea);

- II (in 2024)—line the above-mentioned administrative territorial units, to which are added 19 counties (Bacău, Brașov, Caraș-Severin, Călărași, Cluj, Covasna, Galați, Giurgiu, Harghita, Ilfov, Mehedinți, Neamț, Prahova, Sibiu, Satu-Mare, Sălaj, Teleorman, Vaslui, and Vâlcea);

- III (in 2025)—in 19 other counties (Alba, Arad, Argeș, Bihor, Bistrița-Năsăud, Botoșani, Brăila, Buzău, Constanța, Dâmbovița, Dolj, Gorj, Hunedoara, Ialomița, Maramureș, Olt, Suceava, Timiș, and Tulcea), including the administrative territorial units included in phases I and II.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| AGIS | Alert generation information system |

| CSCA | Computer system for creating alerts |

| CSGA | Computer system for generating alerts |

| DFV | Domestic and family violence |

| EM | Electronic monitoring |

| EMD | Electronic surveillance devices (D1, …, Dn) |

| EMIS | Electronic Monitoring Information System |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| GSM | Global System for Mobile Communications |

| ICT | Information and communications technology |

| ID | IDentification |

| ISSC | Information system for signal creation |

| LBS | Location based services |

| NAP | National Administration of Penitentiaries |

| NESC | National Electronic Surveillance Centre |

| PIN | Personal identification number |

| RFT | Radiofrequency technology |

| SIM | Subscriber identity module |

| SNSEC | Single national system for emergency calls |

| STS | Special Telecommunication Services |

| VAT | Value added tax |

Appendix A

| State | Electronic Monitoring Features |

|---|---|

| Austria |

|

| Belgium |

|

| Cyprus |

|

| France |

|

| Germany |

|

| Great Britain |

|

| Greece |

|

| Switzerland |

|

References

- Alhmiedat, Tareq, and Majed Aborokbah. 2021. Social Distance Monitoring Approach Using Wearable Smart Tags. Electronics 10: 2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avătămăniței, Sebastian-Andrei, Cătălin Beguni, Alin-Mihai Căilean, Mihai Dimian, and Valentin Popa. 2021. Evaluation of Misalignment Effect in Vehicle-to-Vehicle Visible Light Communications: Experimental Demonstration of a 75 Meters Link. Sensors 21: 3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belur, Jyoti, Amy Thornton, Lisa Tompson, Matthew Manning, Aiden Sidebottom, and Kate Bowers. 2020. A systematic review of the effectiveness of the electronic monitoring of of-fenders. Journal of Criminal Justice 68: 101686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beumer, Soraya, and Marianne Kylstad Øster. 2016. Survey of Electronic Monitoring in Europe: Analysis of Questionnaires. Paper presented at 10th CEP Electronic Monitoring Conference, Balsta, Sweden, November 8–10; Available online: http://cep-probation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/CEP-EM-Analysisquestionnaire2016.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Borseková, Kamila, Jaroslav Klátik, Samuel Koróny, Peter Krištofík, Peter Mihók, and Martin Orviský. 2020. Sustainable Policy Measures Based on Implementation of Digital Technologies in Corrections: Exploratory Study from Slovakia and Beyond. Sustainability 12: 8643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borseková, Kamila, Peter Krištofík, Vaňová Anna, Samuel Korony, and Peter Mihok. 2018. Electronic monitoring as an alternative form of punishment: An exploratory study based on European evidence. International Journal of Law and Interdisciplinary Legal Studies 4: 39–51. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/19kpfOremmIMm6AXd6zwRboDLNN9NhZQX/view (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe. 1992. Recommendation No. 16 on the European Rules on Community Sanctions and Measures. Strasbourg: Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe, Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16804d5ec6 (accessed on 12 April 2022).

- Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe. 2014. Recommendation No, 4 to Member States Regarding Electronic Monitoring. Aadopted on 19 February 2014, at the 1192nd Reunion of Deputy Ministers. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16806f4085 (accessed on 9 April 2022).

- Costea, Vladimir-Adrian. 2018a. The application of electronic monitoring systems in Romania: How and in what ways does electronic surveillance facilitate a convicted person’s reintegration into society? Constitutional Law Review 1: 41–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costea, Vladimir-Adrian. 2018b. The dynamics of overcrowding and detention conditions in Romanian prisons during 1990–2017. Revista Română de Sociologie 3–4: 303–40. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. 1964. The European Convention on the Supervision of Conditionally Sentenced or Conditionally Released Offenders. ETS No. 51. Strasbourg: Council of Europe, Available online: https://rm.coe.int/168006ff4d (accessed on 12 April 2022).

- Daubal, Mohammed, Olajumoke Fajinmi, Lars Jangaard, Niko Simonson, Brett Yasutake, Joe Newell, and Mohamed Ali. 2013. Safe Step: A Real-Time GPS Tracking and Analysis System for Criminal Activities Using Ankle Bracelets. Paper presented at 21st ACM SIGSPATIAL International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems, Orlando, FL, USA, November 5–8; p. 515. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsche Welle. 2022. Offender Tracking Systems: The Electronic “Ankle Bracelet”—More of a Mental Concept. Available online: https://www.dw.com/en/the-electronic-ankle-bracelet-more-of-a-mental-concept/a-37090613 (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- Dünkel, Frieder. 2018. Electronic Monitoring in Europe—A Panacea for Reforming Criminal Sanctions Systems? A Critical Review. Kriminologijos Studijos 60: 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Court of Human Rights. 1950. The Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ETS No. 5). Strasbourg: Council of Europe, Available online: https://www.echr.coe.int/documents/convention_eng.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Farhadi, Maryam, Ismail Masood, and Fooladi Masood. 2012. Information and communication technology use and economic growth. PLoS ONE 7: e48903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Inspectorate of Romanian Police. 2021. Ordinul Comun (…) No. 97/51473/48/2021 Pentru Aprobarea Regulamentului de Organizare și Funcționare al Comitetului Tehnic. Bucharest: General Inspectorate of Romanian Police, Available online: https://www.sts.ro/files/userfiles/112%20-%20nou/20201206%20-%20legi/regulamentul-de-organizare-si-functionare-a-comitetului-national-de-coordonare-a-activitatii-sistemului-national-unic-pentru-apeluri-de-urgenta-precum-si-a-secretariatului-tehnic.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Graham, Hannah, and Gill McIvor. 2017. Advancing electronic monitoring in Scotland: Understanding the infuences of localism and professional ideologies. European Journal of Probation 9: 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granja, Rafaela. 2021. The Invisible Implications of Techno-Optimism of Electronic Monitoring in Portugal. Comunicação e Sociedade 40: 247–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henneguelle, Anaïs, Benjamin Monnery, and Annie Kensey. 2016. Better at Home than in Prison? The Effects of Electronic Monitoring on Recidivism in France. Journal of Law and Economics 59: 629–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hucklesby, Anthea, Kristel Beyens, and Miranda Boone. 2021. Comparing electronic monitoring regimes: Length, breadth, depth and weight equals tightness. Punishment and Society 23: 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaila, Narcisa. 2012. Utilizarea Tehnologiei Informatiei in Mediul Economic, 1st ed. Bucharest: Universitară, p. 227. ISBN 978-606-591-571-8. [Google Scholar]

- Jakkhupan, Worapot, and Pongsak Klaypaksee. 2014. A Web-based Criminal Record System Using Mobile Device: A Case Study of Hat Yai municipality. Paper presented at 2014 IEEE Asia Pacific Conference on Wireless and Mobile, Bali, Indonesia, August 28–30; pp. 243–46. [Google Scholar]

- James, Bamisaye Ayodeji, and Adebayo Adeola Abiola. 2021. Internet of Things (IoT) for Sustainable National Economy Development. Information Technology Journal 20: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Richard. 2014. The electronic monitoring of ofenders: Penal moderation or penal excess? Crime, Law and Social Change 62: 475–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karaman Aksentijević, Nada, Zoran Ježić, and Petra Adelajda Zaninović. 2021. The Effects of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Use on Human Development—A Macroeconomic Approach. Economies 9: 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavric, Alexandru, Adrian I. Petrariu, Partemie-Marian Mutescu, Eugen Coca, and Valentin Popa. 2022. Internet of Things Concept in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multi-Sensor Application Design. Sensors 22: 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima Machado, Paulo, Rafael T. De Sousa, Robson De Oliveira Albuquerque, Luis Javier García Villalba, and Tai-Hoon Kim. 2017. Detection of Electronic Anklet Wearers’ Groupings throughout Telematics Monitoring. ISPRS International Journal Geo-Information 6: 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mahu, Iurie. 2020. Monitorizarea electronică—Alternativă la pedeapsa închisorii [Electroning monitoring—An alternative to prison]. Legea şi Viaţa 4–5: 22–27. Available online: https://ibn.idsi.md/ro/vizualizare_articol/103531 (accessed on 9 April 2022).

- Ministry of Administration and Interior. 2019. Informare Despre Proiectul Legislativ Privind Infiintarea și Funcționarea Sistemului Informatic de Monitorizare Electronică; Bucharest: Ministry of Administration and Interior. Available online: https://www.mai.gov.ro/proiect-privind-infiintarea-si-functionarea-sistemului-informatic-de-monitorizare-electronica (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Miron, Ecaterina-Liliana, Mihai Miron, and Gheorghe Pană. 2008. Electronică. Partea I. Brașov: Editura Academiei Forțelor Aeriene “Henri Coandă”, ISBN 978-973-8415-61-4. [Google Scholar]

- Misra, Gourav, Vivek Kumar, Arun Agarwal, and Kabita Agarwal. 2016. Internet of Things (IoT)—A Technological Analysis and Survey on Vision, Concepts, Challenges, Innovation Directions, Technologies, and Applications (An Upcoming or Future Generation Computer Communication System Technology). American Journal of Electrical and Electronic Engineering 4: 23–32. Available online: http://pubs.sciepub.com/ajeee/4/1/4 (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Nancarrow, Heather, and Tanya Modini. 2018. Electronic Monitoring in the Context of Domestic and Family Violence: Report for the Queensland Department of Justice and Attorney-General. Sydney: ANROWS, Available online: https://d2rn9gno7zhxqg.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/22233751/anrows-electronic-monitoring.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- National Agency for Equal Opportunities for Women and Men. 2021. Cadrul Legislativ Necesar Pentru Protectia Victimelor Violentei Domestice Prin Intermediul Unui Program National Integrat; Bucharest: National Agency for Equal Opportunities for Women and Men. Available online: https://anes.gov.ro/guvernul-romaniei-asigura-cadrul-legislativ-necesar-pentru-protectia-victimelor-violentei-domestice-prin-intermediul-unui-programului-national-integrat (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Nellis, Mike. 2014. Understanding the Electronic Monitoring of Offenders in Europe: Expansion, regulation and prospects. Crime, Law and Social Change 62: 489–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nellis, Mike. 2015. Standarde și Etică în Monitorizarea Electronică Manual Pentru Specialiștii Responsabili de Stabilirea și Utilizarea Monitorizării Electronice. Strasbourg: SPDP, Consiliul Europei, Available online: https://rm.coe.int/manual-standarde-si-etica-in-monitorizarea-electronica/168091e565 (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Nellis, Mike, Kristel Beyens, and Dan Kaminski, eds. 2013. Electronically Monitored Punishment: International and Critical Perspectives. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Canh Phuc, and Nadia Doytch. 2021. The impact of ICT patents on economic growth: An international evidence. Telecommunications Policy 46: 102291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistor, Andreea, and Eduard Zadobrischi. 2022. Analysis and Estimation of Economic Influence of IoT and Telecommunication in Regional Media Based on Evolution and Electronic Markets in Romania. Telecom 3: 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduor, Collins, Freddie Acosta, and Everlyne Makhanu. 2014. The Adoption of Mobile Technology as a Tool for Situational Crime Prevention in Kenya. Paper presented at 2014 IST-Africa Conference Proceedings, Le Meridien Ile Maurice, Pointe Aux Piments, Mauritius, May 7–9; Available online: https://zh.booksc.eu/book/33925309/4f8d22 (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Philip de Andrés, Amado, and María Noel Rodríguez. 2013. The Use of Electronic Monitoring Bracelets as an Alternative Measure to Imprisonment in Panama. Technical Advisory Opinion No. 002/2013, Addressed to the Public Ministry and the Ministry of Government of Panama. Belize: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Regional Office for Central America and the Caribbean, Available online: https://www.unodc.org/documents/ropan/technicalconsultativeopinions2013/opinion_2/advisory_opinion_002-2013_english_final.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2022).

- Renzema, Marc, and Evan Mayo-Wilson. 2005. Can Electronic Monitoring Reduce Crime for Medium to High Risk Offenders? Journal of Experimental Criminology 1: 215–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, Marina, Barbara Ryser, and Ueli Hostettler. 2021. Punitiveness of electronic monitoring: Perception and experience of an alternative sanction. European Journal of Probation 13: 262–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanian Government. 2006. Ordonanţa de Urgenţă No. 60 Pentru Modificarea şi Completarea Codului de Procedură Penală (…); Bucharest: Romanian Government. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/74920 (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Romanian Government. 2019. Punct de Vedere Referitor la Proiectul de Lege Pentru Modificarea şi Completarea Legii No. 286/2009 Privind Codul Penal (…); Bp. 557/2019; Bucharest: Romanian Government. Available online: http://mrp.gov.ro/web/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Pdv_Bp.-557_2019-Plx.-128_2020.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Romanian Government. 2021a. Notă de Fundamentare la Hotărârea Pentru Aprobarea Notei de Fundamentare Privind Necesitatea şi Oportunitatea Efectuării Cheltuielilor Aferente Proiectului de Investiţii “Operaționalizarea Sistemului Informatic de Monitorizare Electronică”; Bucharest: Romanian Government. Available online: https://sgg.gov.ro/1/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/HGANEXA.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Romanian Government. 2021b. Notă de Fundamentare la Hotărârea Pentru Stabilirea Aspectelor Tehnice și Organizatorice Privind Funcționarea în Sistem Pilot, Precum și a Celor Privind Operaționalizarea Sistemului Informatic de Monitorizare Electronică; Bucharest: Romanian Government. Available online: http://sgglegis.gov.ro/legislativ/docs/2022/02/c_6g9bd40r53fnjkvts8.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Romanian Government. 2022a. Hotărâre (Proiect) Pentru Stabilirea Aspectelor Tehnice și Organizatorice Privind Funcționarea în Sistem Pilot, Precum și a Celor Privind Operaționalizarea Sistemului Informatic de Monitorizare Electronică; Bucharest: Romanian Government. Available online: https://webapp.mai.gov.ro/frontend/documente_transparenta/433_1644425422_Proiect.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Romanian Government. 2022b. Hotărârea No. 69 Pentru Aprobarea Notei de Fundamentare Privind Necesitatea și Oportunitatea Efectuării Cheltuielilor Aferente Proiectului de Investiții “Operaționalizarea Sistemului Informatic de Monitorizare Electronică”; Bucharest: Romanian Government. Available online: https://sgg.gov.ro/1/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/HGANEXA.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Romanian Government. 2022c. Notă de Fundamentare la Ordonanța de Urgență Pentru Modificarea Legii No. 146/2021 Privind Monitorizarea Electronică în Cadrul Unor Proceduri Judiciare şi Execuţional Penale; Bucharest: Romanian Government. Available online: https://webapp.mai.gov.ro/frontend/documente_transparenta/431_1643978080_Nota%20de%20Fundamentare.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Romanian Government. 2022d. Ordonanţa de Urgenţă No. 14 Pentru Modificarea Legii No. 146/2021 Privind Monitorizarea Electronică în Cadrul unor Proceduri Judiciare și Execuțional Penale; Bucharest: Romanian Government. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/251898 (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Romanian Parliament. 1968. Legea No. 15 Privind Adoptarea Codului Penal al României; Bucharest: Romanian Parliament. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/144628 (accessed on 16 April 2022).

- Romanian Parliament. 2003. Legea No. 217 Pentru Prevenirea și Combaterea Violenței Domestice; Bucharest: Romanian Parliament. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/44014 (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Romanian Parliament. 2009. Legea No. 286 Privind Codul Penal; Bucharest: Romanian Parliament. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/109854 (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Romanian Parliament. 2010. Legea No. 135 Privind Codul de Procedură Penală; Bucharest: Romanian Parliament. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/120609 (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Romanian Parliament. 2013. Legea No. 254 Privind Executarea Pedepselor şi a Măsurilor Privative de Libertate Dispuse de Organele Judiciare în Cursul Procesului Penal; Bucharest: Romanian Parliament. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/150699 (accessed on 17 April 2022).

- Romanian Parliament. 2021a. Expunere de Motive Asupra Legii Privind Monitorizarea Electronică în Cadrul Unor Proceduri Judiciare şi Execuţional Penale, Precum şi Pentru Modificarea şi Completarea Unor Acte Normative; Bucharest: Romanian Parliament. Available online: http://www.cdep.ro/proiecte/2020/100/20/9/em180.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- Romanian Parliament. 2021b. Legea No. 146 Privind Monitorizarea Electronică în Cadrul Unor proceduri Judiciare și Execuțional Penale; Bucharest: Romanian Parliament. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/242354 (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Rusu, Vitalie. 2021. Localizarea sau Urmărirea Prin Sistemul de Poziţionare Globală (GPS) ori Prin Alte Mijloace Tehnice. Vol. Conferinței cu Participare Internațională, Facultatea de Drept și Științe Sociale, Universitatea de Stat “Alecu Russo” Bălți, Ed. a 10-a, 8 Octombrie 2021, vol. 1, 11–16. ISBN: 978-9975-50-271-9. Available online: http://dspace.usarb.md:8080/jspui/handle/123456789/5460 (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Spiezia, Vincenzo. 2012. ICT investments and productivity: Measuring the contribution of ICTS to growth. OECD Journal: Economic Studies 1: 199–211. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/economy/growth/ICT-investments-and-productivity-measuring-the-contribution-of-ICTS-to-growth.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2022). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tamaş, Ilie, and Pavel Năstase. 2008. Bazele Tehnologiei Informaţiei şi Comunicaţiilor. Bucharest: Infomega. [Google Scholar]

- Tofan, Mihaela, and Ionel Bostan. 2022. Some Implications of the Development of E-Commerce on EU Tax Regulations. Laws 11: 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vîrgolici, Horia. 2014. Elemente de Tehnologia Informației. Bucharest: Fundația “România de Mâine”. [Google Scholar]

- Vitálišová, Katarína, Anna Vaňová, and Kamila Borseková. 2019. Benefits and risks associated with the electronic monitoring of accused and convicted persons implementation from the community life point of view. Paper presented at 7th Central European Conference in Regional Science, Sopron, Hungary, October 9–11; Available online: http://real.mtak.hu/116284/7/cers-kotet-2020.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Wallace-Capretta, Suzanne, and Julian Roberts. 2013. The evolution of electronic monitoring in Canada. From corrections to sentencing and beyond. In Electronically Monitored Punishment: International and Critical Perspectives. Edited by Mike Nellis, Kristel Beyens and Dan Kaminski. London: Routledge, pp. 44–62. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, Romy, Ebba Herrlander Birgerson, Roberta Julian, Ron Frey, Peter Lucas, Kimberley Norris, and Mandy Matthewson. 2021. Evaluation of Project Vigilance: Electronic Monitoring of Family Violence Offenders; Australia: Tasmanian Institute of Law Enforcement Studies (TILES), University of Tasmania, Australia, CRICOS. Available online: https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/images/stories/committees/SCLSI/Inquiry_into_Victorias_Justice_System_/Submissions/168._attach1_McAuley_Services_for_Women_redacted.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Yeh, Stuart S. 2010. Cost-benefit analysis of reducing crime through electronic monitoring of parolees and probationers. Journal of Criminal Justice 38: 1090–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Stuart S. 2015. The Electronic Monitoring Paradigm: A Proposal for Transforming Criminal Justice in the USA. Laws 4: 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| For | Against |

|---|---|

|

|

| Main Mandatory Principles of EM That Should Be Complied with | Execution Conditions of EM during Different Phases of Criminal Proceedings |

|---|---|

|

|

| Types of Alerts and Reasons for Their Generation | Applicable Procedures by Type of Alert |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bostan, I. Electronic Surveillance in Court Proceedings and in the Execution of Criminal Penalties: Legislative and Logistical Steps Regarding Operationalising the Electronic Monitoring Information System (EMIS) in Romania. Laws 2022, 11, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws11040054

Bostan I. Electronic Surveillance in Court Proceedings and in the Execution of Criminal Penalties: Legislative and Logistical Steps Regarding Operationalising the Electronic Monitoring Information System (EMIS) in Romania. Laws. 2022; 11(4):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws11040054

Chicago/Turabian StyleBostan, Ionel. 2022. "Electronic Surveillance in Court Proceedings and in the Execution of Criminal Penalties: Legislative and Logistical Steps Regarding Operationalising the Electronic Monitoring Information System (EMIS) in Romania" Laws 11, no. 4: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws11040054

APA StyleBostan, I. (2022). Electronic Surveillance in Court Proceedings and in the Execution of Criminal Penalties: Legislative and Logistical Steps Regarding Operationalising the Electronic Monitoring Information System (EMIS) in Romania. Laws, 11(4), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws11040054