Abstract

Coastal and estuarine margins are considered natural resources with various functions and are covered by different management and protection tools. In Portugal, the Maritime Public Domain (MPD) aims to regulate property in maritime and coastal areas, assuming that these are public resources of the nation. Little is known, however, about how the MPD considers estuarine margins, which are also valuable, and vulnerable, environmental areas. This article analyses how the concept of MPD applies to the estuarine margins in Portugal. Moreover, as this concept has been subsequently adopted by other countries with close roots such as Angola, Brazil, and Mozambique, this paper also explores if estuaries are further considered in their legislation. For this purpose, it undertakes an analysis of legal documents establishing the MPD, focusing on the definition, types of areas where it applies, the width of the margins, ownership, and use restriction. The findings show that estuaries are considered by the MPD in Portugal and in the similar instruments of the other three countries. Nevertheless, their approaches differ, especially on the width of margins and the flexibility of the ownership regime, suggesting that the potential to protect margins has not been globally reinforced by the countries adopting MPD after Portugal. This study offers new insights on the MPD and brings to the fore a gap in the literature that deserves to be further explored in other countries with different legal traditions and deepening the analysis on the added value for the protection of estuarine margins.

1. Introduction

The margins of estuarine zones are natural resources with various uses and functions (Clark 1997). They are also frequently associated with fertile agricultural lands, to high levels of biodiversity, and often classified under various protection legal regimes such as, for instance, in the EU countries, the Natura 2000 Network (Birds and Habitats Directives, 79/409/EEC on 2nd of April, amended by Directive 2009/147/EC on 30th of November and 92/43/EEC of 21st of May, respectively), the United Nations’ Ramsar Convention on the conservation of wetlands of 1971, or under national parks and reserves in various world regional contexts.

Estuarine margins are usually understood as terrestrial areas surrounding river mouths affected by tides and by the salinity of the seawater (Pritchard 1967; Potter et al. 2010). Their vulnerability to tides and to the impacts of erosion and flooding can be aggravated by the increasing climate change extreme events (Rocha et al. 2020). They are also often economically attractive, given their landscape values and prime location for housing and tourism development (Schmidt et al. 2012) and consequently exposed to the environmental impacts of those activities. Given their vulnerability to anthropogenic pressures, the prevention of unregulated uses can be vital to safeguard their environmental values. The management of these lands, articulating the protection of the public environmental values with the safeguard of the estuarine communities and activities, can be challenging. Many planning and management tools have been adopted worldwide to improve related decision-making processes (Gibbs et al. 2007). Often, a particular strip of these estuarine margins is considered maritime–terrestrial public domain and subjected to specific constraints. Under the analysis undertaken in this article, the wider the strip and the firmer of the procedural steps to implement the maritime–terrestrial public domain, the stronger the added potential to protect estuarine margins from anthropogenic pressures.

In Portugal, there is a legal instrument named ‘Maritime Public Domain’ (MPD) primarily created to regulate land property on maritime areas, assuming that these are public resources of the nation, i.e., as res publica (public things). The MPD is a property regulatory instrument by defining that the State has legal title over the areas of the MPD. Although it does not determine specific types of land uses allowed on margins, it has potential to protect estuarine areas and to aid planning and management of estuarine areas. MPD is a property regulatory tool and considers that margins affected by tides are state values. By doing so, it safeguards the state’ interests by preventing private uses likely to affect their vulnerability and richness. Moreover, the MPD enables the state’s administrative entities to safeguard public values from the constraints likely to arise from the existence of private property. It may also prevent private uses likely to be affected by the negative impacts of tides, floods, or erosion.

The management of estuarine margins (including the associated land parcels, waters, and the hosted ecosystems) comprises various decisions that must deal with different, often conflicting, data, values, and aims. These decisions may include the definition of non-edificant areas, the re-naturalization of degraded parcels, the assurance of public use, the approval of development projects, or the permitting for private uses. They call for integrated approaches cross-cutting the features and vulnerabilities of these areas, the associated social and economic values, the perspectives of different decision-makers (users, owners, officers, etc.), and the decision-making instruments such as zoning jurisdictions, elaboration, and implementation of permitting regulations, public investments, or management plans, among many others. By preventing private property and consequently private uses, the MPD may facilitate the implementation of protective or restorative measures by management authorities (De Wit et al. 2021). Moreover, by preventing private property in margins vulnerable to damages caused by extreme weather events or sea-level rise, the state is spared to consider any compensation payments to private owners. Conversely, private ownership of the margins increases the state’s dependency on the willingness of privates to implement protection measures or, in extreme situations, on the need to expropriate properties and the associated costs.

Alongside the legislative role to prevent private uses, MDP can also be a source of potential conflicts between the state and landowners. The private use of maritime terrestrial land parcels such as those of estuarine areas dates from ancient times. In some cases, their use is associated with precarious occupation permits; in other cases, some landowners are firmly convinced of their private ownership. For this reason, conflicts between land users who claim ownership and the state, which pre-assumes them as public dominium, are frequent and aggravate the management of the estuarine margins (do Carmo Bargado 2013). This calls for clear rules on the MDP legal documents and transparent implementation procedures. The way legal documents are formulated is likely to influence the protection of coastal and estuarine values and is therefore relevant for their management and governance, as they may hasten or hinder their sustainable development and conservation. Comparative studies of laws among different countries may shed light on possible approaches to related concepts and processes.

Besides Portugal, several Portuguese-speaking countries, Angola, Brazil, and Mozambique, continental countries with extensive and vulnerable coastal strips, including estuaries under environmental protection regimes, have adopted regulatory instruments like the MPD. Little is known, however, about how the related legal documents consider estuarine margins. Since, historically, the legal regimes of these countries derive from a common core—the Portuguese law—it is pertinent to understand how the concept of MPD has evolved regarding estuarine areas and whether its potential for their protection and management has been harnessed and improved. This study not only enlightens the importance of the MPD for the protection and management of estuarine margins, but also offers new insights on the MPD bringing to the fore a gap in the scientific literature that deserves to be further understood.

Among other sources of information, the existing legal regimes of each country are the primary sources of how the major features of the MPD are established. The analysis of these types of documents may shed light on how historically related legal systems are establishing similar tools and how they refer to estuarine margins. This evaluation is useful to further understand how similar its potential for protecting estuarine margins is and to identify potential weaknesses. Since the Maritime Public Domain considers ancient traditions and customary rights of access and free passage along the margins, which are common to several riparian countries, the topic addressed is relevant to the international community.

Focusing on the terrestrial part of the MPD, the primary objective of this study is to disclose if and how the legal documents establishing the MPD refer to estuarine margins, if the width and ownership of the margins are fixed and if the restrictions of use and delimitation process are similarly foreseen. The study, further developing the works of Antunes and Fidélis (2014, 2018), focuses on Portuguese Law. Then, the analysis is extended to the laws adopted in Brazil, Angola, and Mozambique to assess if their legislation has further considered estuarine margins. Although Brazil, Angola, and Mozambique have different social, political, economic, and environmental contexts, they have strong historical roots and shared administrative paths with Portugal until the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Therefore, the design of many national laws has been influenced by shared historical roots and enduring cooperation channels. For this purpose, the article analyses the most relevant legal documents that establish the MPD in the mentioned countries. The analysis is only focused on how estuarine margins are considered by the ‘letter of the law’. Such analysis displays how concepts and approaches are institutionalized under the MPD, but it also paves the way to identify potential strengths and weaknesses for the protection and management of estuaries.

2. Methodological Approach and Data

Bearing in mind the research objectives presented in Section 1, this section presents the methodological steps undertaken (i) to display the current state of the art and the major gaps identified from the literature review, (ii) to analyse the main legislation establishing the concept of MPD in Portugal, Angola, Brazil and Mozambique, and how estuarine margins are considered, and (iii) to compare the major findings.

2.1. For the Literature Review

A literature review was undertaken to display how the concept of MPD is being referred by the scientific community, especially with regard to estuarine margins. It shows if and how the scientific community is discussing the concept of MPD and how it is being related to the protection and management of estuarine margins. The review also provides insights into how the MPD is being studied under specific country contexts and the learning outcomes drawn from them. It does so after the identification of scientific articles published between 2000 and 2021 and subsequent analysis. This period makes it possible to understand whether there was a change regarding the discourse about MPD after the publication of the 2005 Portuguese legislation. The database used only peer-reviewed scientific articles, referenced in the Scopus and Web of Science platforms, given their recognized relevance and credibility within the scientific community, although they can be narrow in relation to law. This choice derives from the interdisciplinary nature of the MPD concept, encompassing different branches of environmental and legal sciences. For this article, they were considered representative of the concerns raised by the scientific community working on this topic.

We identified articles that used as keywords the terms ‘domínio público maritimo’, ‘maritime public domain’, ‘maritime-terrestrial public domain’, and ‘terrenos de marinha’ as topic, part of the title or abstract, or keyword. Articles were screened and the ones considered eligible for analysis were those mentioning the MPD, discussing its concepts, referring to conflicts between public versus private property on estuarine margins, or discussing its role for the protection of estuarine margins. The results returned by the query based on the chosen keywords show a lack of specific studies corresponding to the research objectives set out for this article. Nonetheless, a few contributions related to MPD are worth mentioning and are useful to contextualize the topic in the literature.

2.2. For the Analysis of the MPD Legal Documents

The analytical approach to the study of how estuaries are considered under the MPD of Portugal, Angola, Brazil, and Mozambique first comprised the identification of the primary legislative documents that configure the MPD in each country, followed by a detailed reading and analysis of their content. The documents were identified and accessed on online legislative free access databases of the referenced countries, as indicated in Table 1. These include the constitution of each country as well as the laws or decrees that establish the MPD.

Table 1.

Legal documents analysed.

The documents were analysed to see how MPD is established under the letter of the law and how estuaries are considered whether expressly or implicitly. The study of the documents included careful reading and word searching, it was restricted to their reading. Their historical or political framework was not considered in the analysis. The analysis explored various terms relevant to display the features of the MPD as established by each country, such as ‘maritime public domain’, ‘margins’, ‘estuarine margins’, ‘ownership’, ‘restrictions of use’, and ‘delimitation processes’. As mentioned before, the analysis of these types of documents sheds light on how historically related legal systems are establishing similar tools and how they refer to estuarine margins.

2.3. For the Comparative Analysis

The concerns driving the comparative analysis had in mind the gaps mentioned in the literature review and their potential relevance for the planning and management of estuarine margins. They are structured into the following major topics:

- How is the MPD defined (to understand if the concepts are similar or different approaches are adopted);

- If estuaries are explicitly or implicitly considered (to understand if the legislation recognizes the value of estuarine margins as state dominium);

- How wide are the margins (to understand the extension of the margin considered under the MPD on estuarine areas);

- What ownership regime applies (to understand if margins are state property or if the ownership varies);

- Is there a delimitation process established (to assess if a delimitation procedure is firmly defined);

- Are there limits established to the use of estuarine margins (to understand if the MPD rules regulate the use of estuarine margins).

Following the analytical steps described above, this original research focuses on the content of the MPD legislation of four continental countries with wide coastal strips including estuarine areas with environmental classified values.

3. Findings

3.1. The Maritime Public Domain and the Protection of Estuarine Margins in the Literature

This Section displays how the concept of maritime public domain is being referred to by the scientific community, especially with regard to estuarine margins. The concept of MPD was found in articles associated with two major topics of concern. One group embraces articles referring to the need to protect margins from natural risks and the role of ownership. Another group refers to embraces articles discussing the legal framework establishing the MPD and the protection and management of the margins.

Associated to the group of authors referring to the ownership of margins and the role for protection, a few contributions may be outlined. Many of the identified authors appear to assume that estuarine margins are usually private. For these, estuarine margins ownership is often associated with management constraints, since many interventions, being related to rehabilitation, the control of invasive species, or environmental monitoring, may be thwarted by private owners (Fouts et al. 2017; Hindman et al. 2014; Provencher et al. 2012). Similar constraints are referred to when owners carry out works to protect their property without integrated planning approaches or taking into due account neighbours’ parcels and associated biodiversity and habitats (Smith et al. 2017; Almar et al. 2012; Gabriel and Bodensteiner 2012; Jones and Strange 2009; Banning and Bowman 2009). On the contrary, other authors reflect the understanding of margins as public assets and managed under integrated approaches linking the environmental vulnerabilities with social and economic concerns. Examples of these are from authors studying the implementation of sand feeding operations in maritime public domain areas in Portugal (Marinho et al. 2019) or when studying the use of concessions of certain shoreline parcels under the public domain in Spain (Palazón et al. 2018). None of these studies discuss the implications of the ownership type over the management and planning processes of coastal or estuarine areas. However, with limited analysis of the concept, other authors (Schmidt et al. 2012; Medeiros and Cabral 2013) refer to the MPD in the context of planning and management of coastal and estuarine areas. Schmidt et al. (2012) refer to the shorelines as ‘areas where land and sea coalesce, where human managing institutions often splinter where the waves break’ (Schmidt et al. 2012, p. 314). These authors explain that governance in maritime margins is in constant adaptation but in ‘a patchy manner’. Other concerns are also brought to the fore by Carneiro (2007) that, in the context of Portugal, the MPD is considered an integrated shoreline management tool and stresses its role to implement coastal and estuarine management policies and its allegedly critical importance to limiting human settlements on margins. Still, this author also suggests that some overlaps between the margins identified under the MPD and the land-use and water resources plans may lead to conflicting understandings and question the potential of the MPD. However, the privatization of coastal zones may positively affect the promotion of economic development and resource conservation it requires robust governance systems to prevent abuse and mismanagement (Cabral and Aliño 2011). Nevertheless, the fragmentation of ownership is a constraint for their integrated management (De Wit et al. 2021). These authors consider that the MPD can be a useful tool for environmental protection and management in countries where the property legal system has Roman or Islamic roots.

Out of the other group of authors referring to the MPD and the associated legal contexts, a few contributions are also worth outlining. The concept of MPD is often raised to highlight the historical foundations, which, in the context of France, date from the Roman Empire and traditional principles regarding the MPD (Bordereaux 2014). According to this author, this may help to better grasp the coastal legislation and contribute to integrated perspectives, as in the context of France. An overview of the MPD in Brazil, through a brief description of the historical evolution, implementation, and management of the terrenos de marinha (margins lands) is also used for a better understanding of the evolution of a particular coastline area (de Mesquita et al. 2013). In contrast, other authors refer to the need to update MPD related laws in order to improve coastal zone management like in Lebanon, criticized for dating from 1925 (Meliadou et al. 2012), or in Italy, when compelled to integrate developments of international law (Rochette 2009). It is also the object of criticism on how it is implemented given some existing abusive uses over margins and of calls for its redesign using better knowledge, GIS tools, and stronger management measures (Pinho 2007). Similar approaches can be seen in relation to the Cuban maritime terrestrial public domain by Monzón Bruguera and Herrera Machado (2019). When referring to the Norwegian context, Skar and Vistad (2013) stress that the existence of ambiguous legislation can influence the use of the coastal margins and that, as access to coastal areas is free, conflicts with the existence of private property are frequent. These authors refer to the Portuguese MPD as an example and an alternative to the private Norwegian property regime, along a foreshore or river. A different perspective, but also relevant, is the study of the normative practice of public domain applied to detached parcels in Croatia, where the related obstacles for land registration procedures suggest the need for law amendments (Perkušić 2005).

Loopholes in the implementation of the MPD such as variable criteria applied in different land parcel concessions, namely on their limits and area, annual fees, or distance to the waterline, are said to challenge its credibility (Prieto 2014, Prats 2013). Bearing in mind that the MPD is mainly concerned with land property and consequent ability to use, legal factors such as jurisdiction, tenure, and liability are considered significant constraints for a successful protection of margins and often considered more critical than the availability of scientific expertise (Mckenna et al. 2005). Billé (2008) adds that rather than entrusting the governance of margins to a single entity and related rules, it should be based on processes instead of procedures and supported by a network of land and marine spatial plans at all scales. Although recognizing the need to prevent abusive occupations on the margins, states do not always have adequate resources or information to reinforce their protection and of the associated natural resources, favouring economic over environmental values (Knox and Meinzen-Dick 2001). As coastal and estuarine zones are commonly perceived as the frontier between maritime, coastal, and land laws, including the MPD, under the joint jurisdiction of several entities, too few countries treat them together in a unified framework (Clark 1997). Attempts to deal with conflicts associated with their different approaches are often similar, disregarding the varied features of coastal environments and planning and management contexts (Fernández-González et al. 2020).

From the brief literature presented in this section, four major conclusions can be outlined, as follows:

- (i)

- There are a limited number of scientific articles about the MPD and a lack of systematic studies about the concept and its added value for the protection of coastal and estuarine margins;

- (ii)

- References to the MPD were found in relation to several countries such as Brazil (Medeiros and Cabral 2013; de Mesquita et al. 2013), Canada and the United States of America (Smith et al. 2017; Fouts et al. 2017; Hindman et al. 2014; Provencher et al. 2012; Almar et al. 2012; Gabriel and Bodensteiner 2012; Banning and Bowman 2009; Jones and Strange 2009) Croatia (Perkušić 2005), Cuba (Monzón Bruguera and Herrera Machado 2019), France (Bordereaux 2014; De Wit et al. 2021), Italy (Rochette 2009), Lebanon (Meliadou et al. 2012), Norway (Skar and Vistad 2013), Philippines (Cabral and Aliño 2011), Portugal (Marinho et al. 2019; Schmidt et al. 2012; Carneiro 2007; Pinho 2007), and Spain (Palazón et al. 2018; Prieto 2014; Prats 2013), but none undertake a detailed and thorough analysis on how MPDs are established;

- (iii)

- For Angola and Mozambique, no references were found at all;

- (iv)

- Despite the recognition in the analysed literature of the relevance of ownership on estuarine margins, and the complexity of rights at stake, for their safeguarding and management, there is scant, if any, discussion regarding how estuaries are considered by the MPD, the width of the estuarine strip usually covered, and how the ownership regime is established and implemented.

None of the articles cited above undertake a detailed analysis of how MPDs are established in specific national contexts. This article enriches the context mentioned above with a closer insight into the concept of the MPD, as established in Portugal and three other Portuguese-speaking countries, and how estuarine margins are considered.

3.2. The Maritime Public Domain in Portugal

This Section concentrates on the Portuguese context, highlighting the historical evolution of the legislative framework, the concepts underlying the MPD, and its relationship with the protection and management of estuarine areas. The public domain of a state is the set of resources that the administration uses to fulfil the collective interest of a nation (Amaral and Fernandes 1978). The public domain can be divided, among others, into the aquatic domain, road domain, air domain, military domain, and monumental and artistic domain (Caetano 1983). The aquatic public domain includes the maritime public domain, the river and lake public domain, and the public domain of the remaining waters (Law no. 54/2005, of 15 November, art. 2(1)). The aquatic public domain may ‘belong to the State, the Autonomous Regions, the municipalities or the parishes’ (Law no. 54/2005, of 15 November, art. 2(2)). Before describing the current main characteristics of the Portuguese MPD, a few historical notes are worth mentioning. The evolution of the MPD was shaped by three fundamental stages. Table 2 summarises their main features.

Table 2.

Main stages of the MPD in Portugal, with reference to each legal regime.

The first stage began in 1864 with the introduction of the notion of the MPD in Portugal. Until that date, various precedent laws1 already referred to the existence of crown assets, but not in such a specified manner. The need to allow free access to waters, national defence, or security in the event of a naval conflict and the availability of land for the execution of hydraulic works was present in the creation of the MPD. Although the 1864 regime established that the margins of coastal and estuarine waters were part of the MPD, it did not define their width. In 1892, a first legal reference was made to the width of the margins, which would range between 3 and 30 metres, and exceptionally, 50 metres measured from the line of maximum tide (Decree no. 8 of 5 December 1892 on the Organisation of Hydraulic Services and its staff). In maritime and estuarine waters, it is measured from the line of maximum astronomical high tides. The assumption of a public maritime domain has interfered with the private ownership of parcels of the sea and estuarine beds and margins. Many plots of land could have been private before the creation of the iuris tantum presumption (a presumption that the law allows to be rebuttable, Fisk 1925), according to which they would become part of the public domain. Since then, the ownership of the margins has been the cause of many conflicts between private owners and the state.

The second stage lasted from 1971 to 2005 and had no significant changes to the former context but the merging of existing legislation into Decree-Law no. 458/71 of 5 November.

The third and current stage began in 2005, with the enactment of Law no. 54/2005, of 15 November, which establishes the ownership system of water resources. This law is associated with a legislative package that also included Law 58/2005, which approved the Water Law, transposing into national law the Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000, and establishing the bases and institutional framework for the sustainable management of water. Law 54/2005 corresponds, mutatis mutandis, to Chapters I and II of the previous Decree-Law 468/71.

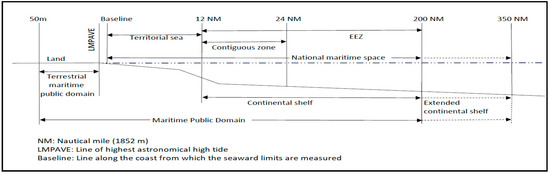

Table 3 summarizes the main features of the MPD, and Figure 1 illustrates the concept and outlines the terrestrial part of the maritime public domain.

Table 3.

Major features of the Portuguese MPD according to Law no. 54/2005 of 15 November.

Figure 1.

Spaces of the Portuguese MPD (designed by the authors).

According to this law, the MPD integrates coastal and territorial waters; inland waters subject to tidal influence in rivers, lakes, and lagoons; the bed of coastal and territorial waters and of inland waters subject to tidal influence; the seabed contiguous to the continental shelf, covering the entire exclusive economic zone; and the tidal inland and coastal water margins.

The MPD not only encompasses maritime space but goes beyond it, if the legislator, when defining it, also includes the areas with tidal influence (estuaries and coastal lagoons) with their beds and margins. Concerning the EEZ, the state only has rights over existing living and mineral resources and not, as in the territorial sea, over the water column. Those resources are not part of the state’s public domain, and for that reason, although EEZ is part of the national maritime space, it is not integrated into the MPD. Moreover, by including areas influenced by tide, it covers the terrestrial margins not only of coastal but also of lagoons and estuarine areas, these being the terrestrial part of MPD. It can be inferred from the provisions of the legal documents that estuarine areas are included, though not explicitly mentioned. In estuarine contexts, most of these margins have a width of 50 m measured from the line of maximum astronomical high tide.

The areas covered by the MPD belong to the state. Nevertheless, since it is not always clearly visible who owns the areas integrated in the MPD, they are often treated as res nullius (a thing with no owner) and unduly appropriated. Legally, those resources are owned collectively, which implies that everyone has certain traditional rights (res communis omnium), and as such, their regime is that of imprescriptibility, unpledgeability, and non-appropriability. The state has an effective right of ownership, more than a simple title on the MPD, yet unavailable and limited as it cannot be alienated. It may, however, grant permits for private uses. In other words, the state has a true property right over the public domain, but since this right is subtracted from legal commerce, it is covered by legal-administrative commerce, and it is, therefore, an administrative property right (Moniz 2005, p. 77). Consequently, the Portuguese MPD is close to a mixture of res communis omnium and res publica. It must also be mentioned that there are parcels of land that the law may consider private. To be recognized as private, land parcels must be subjected to judicial recognition of former private ownership and a delimitation procedure, which consists of their subtraction from the public domain. Judicial recognition is based on documentary evidence that the land was already private before 1864, 1868 when located in coastal cliffs, or 1951 if located in an urban settlement outside the zone of risk of erosion or sea invasion and occupied by construction prior to that year. As the collection of relevant documents is often difficult for the interested parties, many conflicts arise between the state and the users of the margins that attempt to exclude their areas from the public domain, the so-called delimitation process (Júdice and Figueiredo 2015; do Carmo Bargado 2013; Miranda 2013).

Under the current regime, there can be three types of use and occupation of the margins, namely public, private use under a permit, and private. In the land management processes, public administration can authorize the private use of parcels of the terrestrial MPD by issuing specific and temporary permits, such as concessions, authorizations, or licenses. These require the payment of a fee. When a process of delimitation is successful, a set of permanent charges and restrictions of public utility are imposed on the private parcels of land, reducing its property rights. Among those restrictions is to consider the delimitated area as non aedificandi, the need to require permits for specific uses, or the guarantee of free access to beaches and water bodies, among others. Unfortunately, these restrictions and easements are not fully advertised by the land registry offices, and thus landowners often transfer land parcels that they believe their own, with neither burdens nor strict scrutiny.

It is worth outlining that the existence of the MPD, per se, does not regulate the use of estuarine margins, but it is used as a driver for land-use planning of those spaces. The link between MPD and planning and management lies, for instance, in the practical aspect that the MPD alone is the supporter of the availability of these areas, for instance, for public intervention, if necessary. Whereas for planning, the question of property may not be significantly relevant, for the protection, enhancement, and restoration of the different natural and environmental resources existing on estuarine areas, the MPD may assume special relevance. The use of estuarine margins is regulated by the regime that manages all water resources2 established through permitting and protection plans. For estuarine areas, the law establishes specific instruments3 such as the Estuary Management Plans, which aim to protect the waters, beds, margins, and inherent ecosystems, as well as the social, economic, and environmental development of the surrounding land area. They should also offer guidelines for the use of estuarine margins and safeguard urban, recreational, and tourist sites, as well as landscapes of particular interest (Fidélis et al. 2012). In addition to those plans, for the transitional water margins (estuarine margins) located in urban areas, several municipal planning instruments are also applied, such as municipal master plans and urbanisation plans. Nevertheless, all the measures established by these plans must fully respect the MPD.

3.3. The Maritime Public Domain in Angola, Brazil, and Mozambique

This Section undertakes a brief comparative analysis of how three Portuguese-speaking coastal States consider the regulation of estuarine margins. The analysis focuses only on the current MPD regimes of Angola, Brazil, and Mozambique. Like in Section 3.2, this analysis addresses the concept of MPD as established in the legal documents, if margins of estuaries are considered, if there can be private property over them, and how MPD conditions their use. The following paragraphs describe the main features of the three aforementioned selected countries.

3.3.1. Angola

According to article 15 of the Constitution of the Republic of Angola, the land is originally the state’s property, but it may be transferred to natural or legal persons, considering its rational and practical use. The Angolan Constitution defines that the resources belonging to the public domain are inalienable, imprescriptible, and non-appropriable. Among those ‘resources are the internal waters, the territorial sea, the contiguous seabed, the lakes, lagoons, and river courses, including the respective beds, the beaches, and the maritime terrestrial zone’ (art. 95(1) (a, f) of the Constitution). Article 1(d) of the Land Law of Angola, Law no. 9/04 of 9 November defines what the state’s public domain is, integrating in it the beaches and the coastline. According to this law, reserved land or reserves are those parcels of land that, excluded from the general regime of occupation, use, or enjoyment by natural or legal persons, are allocated, totally or partially, to special purposes. Depending on what is to be protected, these reserves are subdivided into total or partial reserves. However, the strip of coastline of inlets, bays, and estuaries, measured from the line of the highest spring tides, is part of those partial reserves (Law no. 9/04 of 9 November art. 27(7)(c)). In these reserves, all forms of occupation or use that do not conflict with the purposes set out in the respective regulations are permitted. The definition of the width of the areas that are part of the maritime public domain, designated as maritime terrestrial zones, is rendered on a case-by-case basis, and the Angolan government is entrusted with the competence to constitute reserves and define their dimensions. In 2011, by the Presidential Decree no. 232/11 of 23 August, and considering that the Provincial Governments are responsible for the management and control of the urban land of the coastal zone, the lands on the MPD, suitable for the implementation of infrastructures and support equipment, not only on the beaches but throughout all the coasts, were detached from the public domain and integrated into the private domain of those Provincial Governments. This detachment encompasses not only the maritime–terrestrial public domain, but also the 500-meter land protection strip.

3.3.2. Brazil

Article 20 (VII) of the Constitution of the Federative Rep. of Brazil, signed 5 October 1988, considers that marine terrains—terrenos de marinha (TM)—are considered national resources. According to article 2 of Decree-Law no. 9.760/1946, of 5 September, TM cover a strip with a width of 33 m, measured in planimetry to the part of the land, from the position of the mean high tide line of 1831 (Decree no. 4105 of 22 February 1868, art. 1). It applies to parcels on the mainland, on the maritime coast, and on the margins of rivers and lakes, as far as the influence of tides can be observed (Decree-Law no. 9.760/46 of September 5, art. 2). Another concept related to TM is that of the marine terrains ‘add ons’ (in the original ‘acrescidos de marinha’). These result from the receding of water, whereas no modification is generated on the limits of the TM, which remain unchanged (Brito 1996). The origin of the TM was based on the need to defend the territory, considering the interest of preserving such lands for the construction of public infrastructures and military facilities and the boarding and disembarkation of people and goods (Gasparini 2003). Marine terrains belong to the state, are administered by the Secretariat of Union Heritage (SPU), and their occupation follows the old regime of emphyteusis4. In 2015, significant changes were introduced in the tax rates and management model of these public resources, by the Law no. 13.240 of 30 December 2015. The legislation does not foresee the delimitation procedure, but Law no. 14.011, of 10 June 2020 created mechanisms that allow the Federal Government to sell the parcels that the Union has in the marine lands. However, these sales, which have been happening since July 2021, are only possible on land occupied with buildings, excluding the TM located in unoccupied areas. Therefore, in Brazil, it is actually possible to convert TMs into private property, but only current tenants can buy them.

3.3.3. Mozambique

In Mozambique, the soil is considered the property of the state, with this property model being enshrined in its Constitutional Law, defining land ownership as an exclusive right of the state, which has the power to decide the conditions of its use and enjoyment (Constitution of the Rep of Mozambique adopted 16 November 2004, art. 6). The Land Law (Law no. 19/97 of 1 October) of Mozambique provides that the land cannot be sold or, in any way, alienated, mortgaged, or pledged. The state has the power to determine the conditions for the use and enjoyment of land by natural or legal persons. The Land Law defines that total or partial protection zones are part of the public domain (Land Law, art. 6). Areas of total protection are those areas intended for the safeguarding or conservation of nature and the state’s defence (Land Law, art. 7). The strip along the seashore and around islands, bays, and estuaries is considered a partial protection zone (Land Law, art. 8 (c)). So, this strip can, without any difficulty, be considered the maritime public domain. The terrestrial part of the MPD encompasses margins of 100 m, measured from the line of the maximum beach to the interior of the territory (Sea Law, art. 12). No land-use rights may be acquired for the maritime and estuarine margins, but special licenses may be issued to exercise certain activities (Land Law, art. 9). The Ordinance of the Land Law (Decree No. 66/98 of December 8) regulates the use of partial protection zones.

3.4. Comparative Analysis

This Section presents the findings of the comparative analysis of the MPD of the four countries using the analytical factors referred on Section 2. Table 4 summarizes the main features of the MPD of the four countries studied according to these factors.

Table 4.

Comparison of the MPD concepts and related features on the countries considered.

The comparative overview brings to the fore the following main differentiating features:

- In all the countries analyzed, although designated differently, the concepts of MPD include estuarine margins. Nevertheless, the Portuguese regime only refers to them indirectly (referring to inland waters under tidal influence), whereas the other regimes consider them explicitly.

- The width of the estuarine margins encompassed by the MPD vary, being 50 m in Portugal, 33 m in Brazil, and 100 m in Mozambique. In Angola, the width of the margins is established in a case-by-case manner. The importance of the size of the margins is critical, as it can contribute to keeping human activities and settlements away from areas prone to natural risks.

- The type of ownership varies among countries. Only the Portuguese regime provides for the possibility of recognizing portions of the margins as private. In Portugal, the margins can be either public or, in very special cases, private, in contrast with Brazilian and Mozambican regimes where they are considered public. In Angola, the margins can be part of the national public domain or integrate the Provincial Government’s private domain.

- The land-use control regime is present in all systems analyzed and, as in Portugal, the private use of the estuarine margins is possible, under permits or concessions and the payment of fees. Mozambique shows more substantial constraints, in any case.

Taking into consideration the research objectives of this article presented in Section 1, the analysis of the legal documents establishing the MPD in Portugal, as well as in Angola, Brazil, and Mozambique presented in Section 3.3, it is noticeable that the various countries have adopted specific documents and legal rules creating a MPD to safeguard the public ownership of maritime margins, including of those of estuaries. Nevertheless, the detail with which rules are established and their scope for the protection of estuarine margins differs among the countries. The various countries have legal instruments to safeguard the public ownership of the maritime margins, in which estuaries are included, although the width of the margins varies from country to country. There is also a general rule that private use of the shores is conditioned or subject to prior authorization or concession.

4. Discussion

This section discusses the findings of how the MPD of the four countries consider the estuarine margins and interprets the results taking into account the research objectives, the literature review, and the methodology used.

As it mainly regulates the ownership of margins, the MPD in Portugal does not guarantee, but may contribute to, the safeguarding and preservation of these natural resources, such as their biodiversity or stability. When estuarine margins are under public dominium regime, planning and management are facilitated. By remaining public, fewer constraints are likely to be faced when designing and implementing protection rules. This happens, for instance, by preventing potential constraints caused by private owners against state interventions on margins or by preventing private interventions disregarding integrated perspectives. The establishment of the MPD shows how the protection of the estuarine margins is essential and, since then, the existence of this legal concept has influenced how planning and management have been carried out. The concern about preservation is attested, ex gratia, by the statement that Portugal, which has been a world pioneer in developing laws to protect coastal zones (OECD 2011). The concept of MPD ‘was introduced at the end of the 19th century and remains valid today’ (OECD 2011, p. 155). Nonetheless, coastal and estuarine zones have been traditionally perceived as the legal frontier between maritime legislation and coastal and land law, which places them under the joint jurisdiction of several entities, making it challenging to reconcile environmental protection and the safety of urban settlements (including the rise of the average level of marine waters, and the various extreme rippling or flood events). Because of this dichotomy, all estuarine plans must be anchored into mechanisms capable of dealing with potential constraints caused by private land ownership. However, simultaneously, those mechanisms should not undermine the concept of private property, which is a deep-rooted idea entrenched in the character of Latin communities. The way MPD is established in Angola, Brazil, and Mozambique, with equivalent, yet different concepts, can be seen as a development of the Portuguese model. This is evident when considering that specific references to estuarine margins only appear in the cases of Angola, Brazil, and Mozambique, or that a larger width of margins appears in Mozambique. As for the rest of the implementation details, the Portuguese case remains more robust, especially by not allowing the sale of MPD parcels to private owners, as happens in Brazil. The sale of MPD land to private owners tends to put the state in a position of fragility if there is a need for future interventions, as previously mentioned.

The implementation of MPD also depends on the quality of land management instruments such as land-use control, how they are integrated in spatial and estuarine planning, and the resources available for their implementation. Thus, a state with a weaker MPD regime but an effective and well-resourced integrated estuary management may, in practice, have a more efficient estuarine management in comparison with a state with a stronger MPD legislation but weaker governance arrangements.

Considering the potential of MPD to aid the protection and management of estuarine margins referred to in Section 1, the findings suggest different levels of aid offered by the current design of MPD among Portugal, Angola, and Mozambique. Four points are worth making. First, by adopting the concept of MPD and considering, explicitly, estuarine margins within it, its potential role for their protection is similarly acknowledged in the four countries. Second, in the countries where the limit of the margin is defined by law (Portugal, Brazil, and Mozambique), the context for decision-making is more transparent for the various actors involved, whereas in countries where it is decided case by case and left to the discretion of authorities (Angola), this increases uncertainty for authorities, owners, and developers, and vulnerability to lobby public officers. This uncertainty may be aggravated when the legislation allows the transfer of margins to private ownership, as in Angola. Third, if the potential of MPD for protecting estuarine margins is directly proportional to its width, our findings reflect different strengths among the countries, with Mozambique at the top and narrower preferences on Portugal and Brazil. Nevertheless, with wider margins, as in Mozambique, the role of MPD for the protection and management of margins may be threatened as it requires more resources for its implementation and surveillance. In countries with limited technical and administrative resources, as is the case in Mozambique, there may be an increased difficulty and reduced likelihood of effective implementation of the MPD. However, the greater constraints found in the Mozambican regime may reflect a greater concern for the protection of the margins and associated natural resources. The potential for protecting estuarine margins in Brazil is weakened by the possibility opened by the MPD legislation for estuarine land parcels to be sold to their users. Fourth, considering the property regime, the potential of MPD to prevent property conflict on estuarine margins is more substantial in Mozambique as land parcels are public, whereas in the other countries, it is poorer, as private and public property may co-exist (Angola and Brazil), or land parcels may be detached from the MPD (Portugal).

Contrary to the constraints mentioned by Fouts et al. (2017), Hindman et al. (2014) or Provencher et al. (2012), by placing the estuarine margins under public ownership, the existence of the MPD may work as a facilitator of the planning and management process, especially for the preservation of environmental resources. As the legal instruments such as MPD are likely to influence planning and management of estuarine margins, a clear understanding of its specific concepts and procedural details is relevant to prevent conflicts with other existing instruments, such as nature conservation or spatial development plans, and smooth their articulation, in line with the contributions from of Clark (1997); Fernández-González et al. (2020) or Knox and Meinzen-Dick (2001). This article contributed to explaining how the MPD is being established in four different countries with common historical roots but in very different locations, and the related features to protect estuarine margins as public assets.

Three relevant limitations of the analysis undertaken in this paper should be outlined. One is related to the analytical focus, limited to the content of the legislation on the MPD. The implementation of MPD, would also be worthy of future studies using specific methodologies and data. Future studies extending the analysis to interviews with major stakeholders dealing with the MPD could give complementary insights on the topic. Another is related to the focus on the MPD concepts, leaving aside the analysis of other documents and the procedures used to implement MPD and the conflicts that often emerge between private owners and state authorities. Future studies could contribute to overcoming such a gap by looking at press news about conflicts that have emerged around MPD and their location. The extension of such a study to other countries with different legal traditions could also be enriching to clarify the different legal mechanisms adopted to regulate property on estuarine margins. Finally, the scarce scientific literature on the subject was also a significant constraint. Other studies on the MPD may exist in law journals not indexed to Scopus or Web of Knowledge, which escaped from the article search used. Still, the analysis presented in this article shed new and valuable light on the topic and suggested the importance of new studies on the MPD.

5. Conclusions

Despite the relevance of the MPD, it is scantily discussed by the scientific community, and studies on how it is established and how it contributes to the protection of estuarine margins are scarce. The original approach undertaken by this article finds no parallel with other articles referencing the MPD. The analysis of the legal documents establishing the MPD shows that estuaries are considered in Portugal and in Angola, Brazil, and Mozambique. These countries have adopted specific documents and legal rules to safeguard the public ownership of maritime margins, including of those of estuaries. Nevertheless, their contents differ, especially on the width of margins and the flexibility of the ownership regime. Broadly, the scope of MPD, in Portugal and other analyzed countries, is similar but their potential to protect estuarine margins and safeguard human life and goods, by keeping settlements away from areas with risks of erosion and flooding, differs. This exploratory article enlightened the importance of the MPD for the protection of estuarine margins, offered new insights on the MPD and gave evidence of a gap in the literature to be further explored by extending the research to other countries with different legal traditions and deepening the analysis on the implementation processes to better clarify its added value for protecting estuarine margins.

Author Contributions

M.A. undertook the document analysis. M.A. and T.F. developed the concept and structure of the article and wrote the manuscript. M.L.P. revised the final version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Almar, Rafael, Roshanka Ranasinghe, Nadia Sénéchal, Philippe Bonneton, Dano Roelvink, Karin R. Bryan, Vincent Marieu, and Jean-Paul Parisot. 2012. Video-Based detection of shorelines at complex MesoMacro tidal beaches. Journal of Coastal Research 28: 1040–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, Diogo Freitas do, and José Pedro Fernandes. 1978. Comentário à Lei dos Terrenos do Domínio Hídrico. Coimbra: Editora, ISBN 972-32-0242-5. [Google Scholar]

- Antunes, Marco, and Teresa Fidélis. 2014. The Maritime Public Domain—Concept and implementation in different national legal systems. Paper presented at the Poster, International Meeting on Marine Research (IMMR’14), Peniche, Portugal, July 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Antunes, Marco, and Teresa Fidélis. 2018. Domínio Público Marítimo e Terrenos de Marinha. As diferenças na mesma génese de princípios. Paper presented at the Conferência Internacional de Ambiente em Língua Portuguesa (CIALP), Oral presentation, Aveiro, Portugal, May 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Banning, Alison E., and Jacob L. Bowman. 2009. Effects of long piers on birds in tidal wetlands. Journal of Wildlife Management 73: 1362–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billé, Raphaël. 2008. Integrated Coastal Zone Management: Four entrenched illusions. S.A.P.I.E.N.S [Online], 1.2. Available online: http://journals.openedition.org/sapiens/198 (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- Bordereaux, Laurent. 2014. Seashore Law: The Core of French Public Maritime Law. The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law 29: 402–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, Lindoval Marques de. 1996. Imóveis Públicos: Terrenos de Marinha. Terrenos Indígenas. Revista do Tribunal Regional Federal 1ª Região, Brasília, v. 8, n. 4, October/December. Available online: https://bdjur.stj.jus.br/jspui/bitstream/2011/21802/imoveis_publicos_terrenos_marinha.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Cabral, Reniel B., and Porfirio M. Aliño. 2011. Transition from common to private coasts: Consequences of privatization of the coastal commons. Ocean & Coastal Management 54: 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano, Marcello. 1983. Manual de Direito Administrativo, 9th ed. Coimbra: Almedina, vol. II, ISBN 9789724071312. [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro, Gonçalo. 2007. The parallel evolution of ocean and coastal management policies in Portugal. Marine Policy 31: 421–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, John R. 1997. Coastal zone management for the new century. Ocean & Coastal Management 37: 191–216. [Google Scholar]

- de Mesquita, Afrânio Rubens, Carlos Augusto de Sampaio França, Denizard Blitzkow, Marco Antonio Corrêa, Jorge Luiz Alves Trabanco, and Mauro Quandt Monteiro. 2013. Union sea land property and the relative 1831 sea level at Barra do Una beach. Revista Brasileira de Geofísica 31: 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, Rutger, Pénélope Chaubron-Couturier, and Florence Galletti. 2021. Diversity of property regimes of Mediterranean coastal lagoons in S. France; implications for coastal zone management. Ocean & Coastal Management 207: 105579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Carmo Bargado, Manuel António. 2013. O reconhecimento da propriedade privada sobre terrenos do domínio público hídrico. Lisboa: Instituto de Ciências Jurídico-Políticas, Faculdade de Direito da Universidade de Lisboa, Available online: https://www.trg.pt/ficheiros/estudos/o_reconhecimento_da_propriedade_privada.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2021).

- Fernández-González, Raquel, Marcos I. Pérez-Pérez, and Manuel M. Varela Lafuente. 2020. An institutional analysis of Galician turbot aquaculture: Property rights system, legal framework and resistance to institutional change. Ocean & Coastal Management 194: 105281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidélis, Teresa, Fernando Veloso Gomes, Margarida Cardoso Silva, Maria Amélia Antunes, Maria João Burnay, Natércia Cabral, and Vítor Campos. 2012. Planos de Ordenamento de Estuário—Contributos para a sua elaboração e implementação. Relatório do Grupo de Trabalho XIV do Conselho Nacional da Água, Apreciação n.º 01 CNA/2009. Publicações do Conselho Nacional da Água, MAMAOT. Available online: https://conselhonacionaldaagua.weebly.com/uploads/1/3/8/6/13869103/_planos_ordenamento_estuarios_2012.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Fisk, Otis Harrison. 1925. Presumptions, 11 Cornell L. Rev. 20. Available online: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol11/iss1/2 (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Fouts, Kevin L., Neelam C. Poudyal, Rebecca Moore, James Herrin, and Susan B. Wilde. 2017. Informed stakeholder support for managing invasive Hydrilla verticillata linked to wildlife deaths in a Southeastern reservoir. Lake and Reservoir Management 33: 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, Anthony O., and Leo R. Bodensteiner. 2012. Impacts of riprap on wetland shorelines, upper Winnebago pool lakes, Wisconsin. Wetlands 32: 105–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparini, Diógenes. 2003. Direito Administrativo, 8th ed. São Paulo: Editora Saraiva, ISBN 85-02-04044-8. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, David, Aidan While, and Andrew E. G. Jonas. 2007. Governing Nature Conservation: The European Union Habitats Directive and Conflict Around Estuary Management. Environment and Planning 39: 339–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindman, Larry J., William F. Harvey IV, and Linda E. Conley. 2014. Spraying corn oil on Mute Swan Cygnus olor eggs to prevent hatching. Wildfowl 64: 186–96. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289134436_Spraying_corn_oil_on_Mute_Swan_Cygnus_olor_eggs_to_prevent_hatching (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Jones, Russell, and Elizabeth Strange. 2009. An analytical tool for evaluating the impacts of sea level rise response strategies. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal 20: 383–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Júdice, José Miguel, and Figueiredo José Miguel. 2015. Acção de Reconhecimento da Propriedade Privada sobre Recursos Hídricos, 2nd ed. Coimbra: Almedina, ISBN 9789724061535. [Google Scholar]

- Knox, Anna, and Ruth Suseela Meinzen-Dick. 2001. Collective Action, Property Rights and Devolution of Natural Resource Management: Exchange of Knowledge and Implications for Policy. CAPRi working papers No. 11. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), Available online: http://ebrary.ifpri.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15738coll2/id/126267 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Marinho, B., C. Coelho, H. Hansonc, and K. Tussupovac. 2019. Coastal management in Portugal: Practices for reflection and learning. Ocean and Coastal Management 181: 104874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckenna, John, Michael MacLeod, Andrew Cooper, Anne Marie O'Hagan, and James Power. 2005. Land tenure type as an underrated legal constraint on the conservation management of coastal dunes: Examples from Ireland. Area 37: 312–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, Raquel, and Pedro Cabral. 2013. Dynamic modelling of urban areas for supporting integrated coastal zone management in the South Coast of São Miguel Island, Azores (Portugal). Journal of Coastal Conservation 17: 805–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meliadou, Aleka, Francesca Santoro, Manal R. Nader, Manale Abou Dagher, Shadi Al Indary, and Bachir Abi Salloum. 2012. Prioritizing coastal zone management issues through fuzzy cognitive mapping approach. Journal of Environmental Management 97: 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, João. 2013. The ownership and administration of the public hydric domain by public entities. In Série CURSOS TÉCNICOS 3—Direito da água. Lisboa: ERSAR/FDUL, p. 157. ISBN 978-989-8360-16-8. [Google Scholar]

- Moniz, Ana Raquel. 2005. O Domínio Público: O critério e o regime jurídico da dominialidade. Coimbra: Almedina, ISBN 972-40-2447-4. [Google Scholar]

- Monzón Bruguera, Yailén, and Diana Mary Herrera Machado. 2019. Acercamiento a la evolución regulatoria del tratamiento de la zona costera como bien de dominio público en el ordenamiento jurídico cubano’. Universidad y Sociedad. Revista Científica de la Universidad de Cienfuegos 11: 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2011. Environmental Performance Reviews: Portugal 2011. Paris: OECD Publishing, p. 155. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1787/19900090 (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Palazón, Antonio, Isabel López, Virgilio Gilart, Luis Bañón, and Pomares Luis Aragonés. 2018. Concessions within the maritime-terrestrial public domain on the beaches of southeastern Spain. Ocean and Coastal Management 161: 156–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkušić, Ante. 2005. The maritime (public) domain and established rights in the land registers [Pomorsko (opće) dobro i na njemu osnovana prava u zemljišnim knjigama]. Nase More 52: 13–21. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291911999_The_maritime_public_domain_and_established_rights_in_the_land_registers (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Pinho, Luísa. 2007. The role of maritime public domain in the Portuguese coastal management. Journal of Coastal Conservation 11: 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, Ian C., Benjamin M. Chuwen, Steeg D. Hoeksema, and Michael Elliott. 2010. The concept of an estuary: A definition that incorporates systems which can become closed to the ocean and hypersaline. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 87: 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prats, Bartomeu Trias. 2013. Fees, charges, and contributions in the use of the maritime terrestrial public domain. (Developments of the law 2/2013, of May 29). Revista General de Derecho Administrativo 34: 413819. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto, Carlos Villalón. 2014. Aguas y costas: Corresponde a la administración acreditar que los terrenos reúnen características de dominio público marítimo terrestre. a propósito de la desnaturalización del MPDT. Revista General de Derecho Administrativo 37: 10. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, Donald W. 1967. What is an estuary? Physical point of view. In Estuaries. Washington DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science. [Google Scholar]

- Provencher, Bill, David J. Lewis, and Kathryn Anderson. 2012. Disentangling preferences and expectations in stated preference analysis with respondent uncertainty: The case of invasive species prevention. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 64: 169–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, Carolina, Carlos Antunes, and Cristina Catita. 2020. Coastal Vulnerability Assessment Due to Sea Level Rise: The Case Study of the Atlantic Coast of Mainland Portugal. Water 12: 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rochette, Julien. 2009. Challenge, dialogue, action… Recent developments in the protection of coastal zones in Italy. Journal of Coastal Conservation 13: 131–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, Luísa, Pedro Prista, Tiago Saraiva, Tim O’Riordan, and Carla Gomes. 2012. Adapting governance for coastal change in Portugal. Land Use Policy 31: 314–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skar, Margrete, and Odd Inge Vistad. 2013. Recreational Use of Developed Norwegian Shorelines: How Ambiguous Regulations Influence User Experiences. Coastal Management 41: 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Carter S., Rachel K. Gittman, Isabelle P. Neylan, Steven B. Scyphers, Joseph P. Morton, F. Joel Fodrie, Jonathan H. Grabowski, and Charles H. Peterson. 2017. Hurricane damage along natural and hardened estuarine shorelines: Using homeowner experiences to promote nature based coastal protection. Marine Policy 81: 350–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| 1 | In Portugal, the laws were compiled in Ordinances, corresponding to the Afonsina (15th century), Manuelina (16th century), and Filipina (17th century) dynasties. |

| 2 | Decree-Law No. 226-A/2007 of 31 May, on the use of water resources. |

| 3 | Law No 58/2005 of November 29, Article 19. |

| 4 | An ancient real right, long term or perpetual, under which a person has the right to enjoy of another’s estate as if it were their own, conferring the powers relative to the useful domain of the land (use and fruition), and the ability to dispose of its substance. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).