New Financial Action Task Force Recommendations to Fight Corruption and Money Laundering

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. New FATF Recommendations

2.1. New FATF Recommendation #1—Beneficial Owner Reporting Rule

- What prevents a sender/recipient from posing as a beneficial owner when he/she is not in fact the true beneficial owner? Nothing prevents a person from posing as a beneficial owner except that it would be readily detected and punishable by debarment, fines, and imprisonment (Yeh 2020a, 2020b, 2020c). If authorities obtain e-mail or text messages directing the “beneficial owner” to send/receive funds, that would be sufficient to prove that the named person is not in fact the true beneficial owner (because only the beneficial owner can issue instructions). In many cases, it may be easier for investigators to obtain e-mail and text messages (compared to the task of proving that funds are illicit).2 The APUNCAC rule requires the fake beneficial owner to certify information that is demonstrably false. In contrast, the existing AML regime does not require the fake beneficial owner to certify information that is demonstrably false.

- Why not rely on customer identification program (CIP) regulations that require financial institutions to verify the identity of individuals wishing to conduct financial transactions with them? When money laundering occurs, the identity of the beneficial owner is hidden from financial institution personnel. The “customer” is typically a front man or agent of the true beneficial owner who does not reveal the true identity of the beneficial owner. The existing AML regime permits this deception. The APUNCAC regime criminalizes this deception.

- How does the APUNCAC rule address the issue that criminals use anonymous corporate/legal entities to hide illicit funds? The APUNCAC rule would permit investigators to trace the path of illicit funds into and out of anonymous corporate/legal entities. No other strategy would accomplish this.

- Would the cost of implementation be massive? No. The technology already exists and is currently deployed, for example, via the current generation of chip-based secure electronic transaction credit card technology.3 It would be no more expensive than developing a credit card and deploying the credit card to all users.

- Would this rule slow down all manner of legitimate payments? No. Transactions would be processed in the same way that credit card companies process millions of transactions per day. Credit card transactions are designed to be swift and may be automated. Typically, a credit card transaction posts within a day of the transaction. However, improper authorization may cause reversal of the transaction. The same rules and procedures would apply to APUNCAC beneficial owner reporting.4

- What is the threshold amount that triggers the rule? USD 3000. Structuring a sequence of transactions to avoid the threshold is prohibited under APUNCAC.

- What verification is necessary? The use of digital certificate technology provides assurance that the named individual is in fact the person who authorized certification of his/her identity.

- How would the information be stored? The information would be electronically encrypted and transmitted to FINCEN where it would reside in a secure database operated by FINCEN.

- Would this violate privacy laws? No. FATF members have already agreed to collect beneficial owner information.

- Would this require massive amounts of paperwork? No. It would require no more paperwork than is currently required when consumers apply for a credit card and use a credit card.

- Would this massively increase the volume of reports that FINCEN would need to investigate? FinCEN struggles to follow up on the majority of suspicious activity reports.5 However, the volume of money laundering, and FinCEN’s struggle to keep up, are arguably due to a complete failure to trace the beneficial owner whenever funds are transmitted. If front men thought there was a credible probability of being caught, the volume of willing accomplices would shrink, perhaps dramatically. The first order of business is to track the beneficial owner and apply criminal penalties when fake information is supplied. The starting point of every investigation would be to cross-check beneficial owner information against known information drawn from tax databases. This would quickly identify smurfs and other front men whose annual income is grossly inconsistent with the volume of their financial transactions. Recommendation #1 would permit investigators to pressure the front men into cooperation agreements, facilitating the collection of testimony and evidence against the criminals who orchestrate the activity. Investigations would be vastly more efficient than the current strategy of trawling through millions of suspicious activity reports. This could be expected to have a potent deterrent effect.

- How would this work across borders? It would work in the same way that credit card transactions work across borders.

- What is the utility of this rule? The APUNCAC rule would permit investigators to trace the path of illicit funds into and out of anonymous corporate/legal entities. No other strategy would accomplish this.

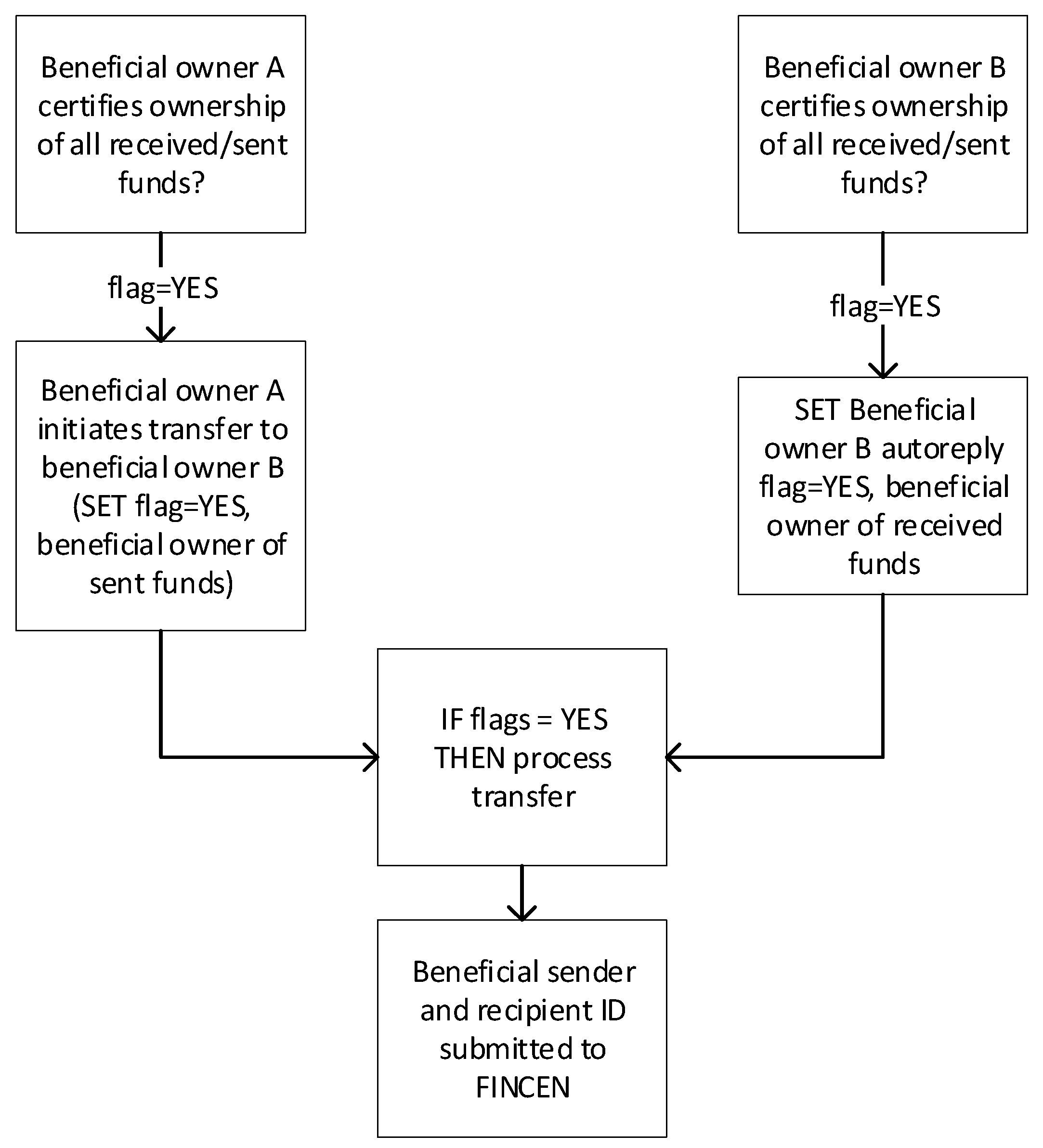

- How would this work if a transaction is conducted via an automated computer program? The program would have to submit certification regarding the beneficial owners involved in the transaction to FINCEN. Essentially, each beneficial owner would need to set a flag on his/her account [“YES, I (the beneficial owner) pre-certify beneficial ownership”] (Figure 1). The program would read the flag for each beneficial owner involved in the transaction. If the flags are set to “YES,” then the program would process the transaction. Otherwise, the transaction would pause until certification is received.

2.2. New FATF Recommendation #2—FINCEN Database

- Would this be a single database, or would each jurisdiction maintain its own database? Since criminals use loopholes in the international financial system, it is desirable to maintain a single integrated database. However, if it is not possible to obtain agreement regarding a single integrated database, each jurisdiction or region may maintain its own database, with provisions to facilitate mutual assistance in cross-border investigations.

- Would debarred individuals be publicly identified? Yes, the FINCEN database would include a publicly accessible list of debarred individuals.

- Would the database be publicly accessible? Only authorized financial crime investigators would have access to beneficial owner information via a secure web portal.

- What about data security? While sophisticated hacking is always a possibility, FinCEN, the U.S. Internal Revenue Service, and Interpol have demonstrated the capacity to securely store and manage large amounts of sensitive data.

2.3. New FATF Recommendation #3—AML Regulations

- Is there a precedent and model for these regulations? Yes. The language is based on U.S. AML laws and regulations.

- What is the most significant difference, vis-à-vis U.S. law and regulations? The most significant difference is the establishment of a beneficial owner reporting rule (see New FATF Recommendation #1) that would apply to nationals of States Parties to the rule and transactions involving funds sent to or from the jurisdiction of States Parties to the rule, and a database maintained by FINCEN that would serve as a central repository of beneficial owner information for each covered financial transaction and would facilitate the investigation and prosecution of financial crime and associated crime (see New FATF Recommendation #2). In addition, New FATF Recommendation #3 would implement regulations intended to isolate debarred individuals.

2.4. New FATF Recommendation #4—Penalties

- Is there a precedent and model for this type of arrangement? Yes. Debarment would isolate recalcitrant individuals who refuse to observe AML regulations in the same way that recalcitrant individuals who continue to do business with individuals on the U.S. Treasury Department’s Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (SDN) List are subject to criminal penalties.

- How would penalties be enforced? Arrests could occur if suspects travel to the jurisdiction of any of the 189 nations that are parties to the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC), which are legally bound by the terms of UNTOC, including the terms whereby any party can request extradition of a suspect from the jurisdiction of another party for violations of UNTOC’s requirements to properly identify customers and maintain records for the purpose of detecting and deterring money laundering.6 Under UNTOC, a suspect who violates a customer identification and recordation requirement may be extradited.7

2.5. New FATF Recommendation #5—Dedicated Courts

- Is there a precedent and model for this type of arrangement? Yes. Ukraine implemented a system where a council of non-Ukrainian international experts review, and vet, individuals nominated for Ukraine’s anticorruption court (Council of Europe 2018; Zabokrytskyy 2020). The law establishing the anticorruption court was signed by Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko, a corrupt oligarch—suggesting that this type of court can be established even when corrupt individuals control the office of the president (UNIAN 2018).

- How would the integrity of these courts be assured? The courts would be periodically evaluated by the UN Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice. Failure of a dedicated anticorruption court or prosecutor to observe the highest standards of judicial or prosecutorial conduct would warrant disciplinary action by the Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice. Such action may include a letter of reprimand, redirection of funding to higher performing courts or prosecutors, or a recommendation to a national judicial council to suspend, demote, or remove a judge or prosecutor whose conduct contributes to unnecessary delays or falls below the highest standards of judicial or prosecutorial conduct.

2.6. New FATF Recommendation #6—UN Inspectors

- Is there a precedent and model forthis type of arrangement? Yes. The International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) was established via a bilateral treaty with the United Nations.8 This “hybrid” UN-backed mission combined international and national capacities working through Guatemalan laws and courts. CICIG successfully investigated and helped prosecute multiple high-ranking Guatemalan officials, ex-military officers, and business elites, and resulted in the imprisonment of the sitting president and vice president in 2015 (Call and Hallock 2020). CICIG investigations led to 1540 indictments in 120 cases involving over 70 illicit networks (Call and Hallock 2020). This experience suggests that it is feasible to implement an international agreement that involves intrusive criminal investigations led by UN investigators even in a country where the rule of law is extremely weak, where powerful and violent criminal cartels have gained control of several government departments, where impunity prevails, and where the prospects for implementing UN inspectors are less than favorable.

- Would there be one mission for all jurisdictions that choose to participate or a separate mission for each jurisdiction? There would be a single mission, involving a single set of UN-backed inspectors who would be available to respond to allegations of corruption. Individual jurisdictions could join via separate agreements.

- What would prevent the type of failure that occurred when Guatemalan President Jimmy Morales chose to end the CICIG arrangement? Unlike CICIG, the mandate of the ICAC would be permanent, not temporary, and could not be ended by refusing to sign an extension to the mandate.

2.7. New FATF Recommendation #7—Obstruction of Justice

- Who decides whether obstruction of justice has occurred? UN inspectors or their surrogates may, at their discretion, seek a judicial opinion from a judge in the state where the investigation is conducted regarding any alleged act involving obstruction of justice.

- What happens if a UN inspector concludes that prosecution for the crime of obstruction has been perverted? If a UN inspector subsequently determines that prosecution, discipline, or oversight of an individual accused of obstruction of justice has been perverted, the inspector would prepare and submit a report to the appropriate prosecuting authorities, disciplinary bodies, parliamentary institutions, or other institutions exercising oversight. The inspector would submit the report to be published online by Transparency International.

2.8. New FATF Recommendation #8—Class Actions

- Is there a precedent and model for this type of arrangement? Yes. Articles 60, 61, and 62 are based on Florida’s version of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act. Article 63 is drawn from U.S. rules of civil procedure.

- What would this accomplish? It would permit an NGO such as International Justice Mission to file a class action and seek treble damages when citizens have knowledge of corruption.

2.9. New FATF Recommendation #9—RICO

- Is there a precedent and model for this type of arrangement? Yes. Articles 60, 61, and 62 are based on Florida’s version of the RICO Act.

- What would this accomplish? It would permit prosecutors to build cases against peripheral individuals such as accountants, attorneys, and financial service personnel who aid and abet money laundering, pressure them into cooperation agreements, and build cases against the criminals who orchestrate the criminal activity.

2.10. New FATF Recommendation #10—Conflicts of Interest

- Is there a precedent and model for these rules? Yes. Articles 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, and 57 are based on New York’s conflicts of interest rules and regulations.

- What would this accomplish? These rules and regulations seek to control conflicts of interest that would otherwise facilitate corruption.

2.11. New FATF Recommendation #11—State Assets

- What would this accomplish? These rules and regulations seek to control corruption in the sale of valuable state assets.

- How would this be accomplished? This would be accomplished by requiring each recipient in a chain of recipients to post information regarding the true beneficial owner on a publicly accessible website designated by the Conflicts of Interest Board, in a form and manner approved by the Board.

2.12. New FATF Recommendation #12—Loans

- What would this accomplish? These regulations seek to control corruption that occurs when “loans” are used to bribe corrupt associates.

- How would this be accomplished? This would be accomplished by requiring public servants to report details of any loan extended or received on a secure website designated by the Conflicts of Interest Board in a form and manner approved by the Board.

2.13. New FATF Recommendation #13—Whistleblowing

- What would this accomplish? It would establish an avenue for whistleblowers to report allegations of corruption.

- How would this be accomplished? The Conflicts of Interest Board would maintain a publicly accessible website to permit any individual to submit information in support of allegations of corruption, criminal activity, or conflicts of interest involving a public servant.

2.14. New FATF Recommendation #14—Transfer Pricing

- What would this accomplish? It would prevent multinational firms from manipulating intercompany pricing and reported cost figures in a way that serves to cheat citizens of tax revenue that would otherwise be available to pay for social services, human services, public services, and government infrastructure.

- How would this be accomplished? Firms that operate within the territory of a State Party would be required to conform to OECD’s Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations, as determined by rule of the Conflicts of Interest Board.

2.15. New FATF Recommendation #15—Public Procurement

- What would this accomplish? It would assist in detecting and deterring procurement fraud.

- How would this be accomplished? Article 58 establishes procedures where a duly qualified independent monitor would have access to all relevant documents and meetings for the purpose of monitoring public tendering and contracting processes and deterring procurement fraud.

2.16. New FATF Recommendation #16—False Claims

- Is there a precedent and model for this Article? Yes. Article 59 is based on the U.S. False Claims Act (FCA).

- What would this accomplish? It would provide incentives for whistleblowers to pursue civil actions when they have knowledge of corruption.

- How would this be accomplished? Article 59 establishes procedures where private individuals who have knowledge of fraud (but were not convicted of criminal conduct arising from their role in the violation) may file a qui tam suit, on behalf of the government, for violations of the FCA. If the government intervenes in the qui tam action, the person bringing the action (the “relator”) is entitled to receive between 15 and 25 percent of the amount recovered by the government through the qui tam action. If the government declines to intervene in the action, the relator’s share is increased to 25–30 percent. Under certain circumstances, the relator’s share may be reduced to no more than 10 percent. If the relator planned and initiated the fraud, the court may reduce the award without limitation. The relator’s share is paid to the relator by the government out of the payment received by the government from the defendant. If a qui tam action is successful, the relator is also entitled to receive legal fees and other expenses of the action from the defendant.

2.17. New FATF Recommendation #17—Campaign Reform

- Is there a precedent and model for this Article? Yes. Article 68 is based on a model campaign finance law developed by the Center for Governmental Studies, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that helps civic organizations and decision-makers to strengthen democracy and improve governmental processes.

- What would this accomplish? Article 68 would reduce the negative influence of large campaign contributions by limiting the size of campaign contributions and establishing a system where competitive candidates who can secure a large number of small contributions receive matching contributions from the public treasury. This effectively increases the resources available to popular candidates and limits the ability of wealthy individuals to outspend their opponents. The law seeks to encourage popular candidates to run against well-financed opponents, thereby serving to moderate the influence of wealthy individuals who may have obtained their wealth through corruption or may seek to preserve their wealth through corruption.

2.18. New FATF Recommendation #18—Conspiracy

- Is there a precedent and model for this Article? Yes, Article 69 is based on U.S. law.

- What would this accomplish? Article 69 makes it a crime to conspire to commit the crimes outlined above. It is often easier for a prosecutor to prove conspiracy than to prove that the associated crime was committed.

2.19. New FATF Recommendation #19—Definitions

- Are there precedents and models for the definitions listed in Article 70? Yes, the definitions are primarily adapted from U.S. law or regulations.

- Why is it important to include definitions? Definitions determine what is included and excluded when laws and regulations are applied.

3. Rationale

4. FATF

- Asia/Pacific Group on Money Laundering (APG) based in Sydney, Australia.

- Caribbean Financial Action Task Force (CFATF) based in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago.

- Council of Europe Anti-Money Laundering Group (MONEYVAL) based in Strasbourg, France (Council of Europe).

- Eurasian Group (EAG) based in Moscow, Russia.

- Eastern & Southern Africa Anti-Money Laundering Group (ESAAMLG) based in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

- Financial Action Task Force of Latin America (GAFILAT) based in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- Inter-Governmental Action Group against Money Laundering in West Africa (GIABA) based in Dakar, Senegal.

- Middle East and North Africa Financial Action Task Force (MENAFATF) based in Manama, Bahrain.

- Task Force on Money Laundering in Central Africa (GABAC) based in Libreville, Gabon.

4.1. FATF Review Process

- (a)

- a jurisdiction is nominated by a FATF member or an FSRB. The nomination is based on specific money laundering, terrorist financing, or proliferation financing risks or threats coming to the attention of delegations; or

- (b)

- a jurisdiction does not participate in an FSRB or does not allow mutual evaluation results to be published in a timely manner; or

- (c)

- a jurisdiction has achieved poor results on its mutual evaluation, specifically:

- it has a non-compliant or partially compliant rating for technical compliance on 20 or more of the 40 FATF Recommendations; or

- it is rated non-compliant or partially compliant on 3 or more core FATF Recommendations; or

- it has a low or moderate level of effectiveness for 9 or more of the 11 Immediate Outcomes, with a minimum of two low ratings; or

- it has a low level of effectiveness for 6 or more of the 11 Immediate Outcomes.

4.2. FATF Blacklist

The success story of the ICRG process includes Israel and Russia. Both countries were included on the very first public statement in 2000. Both countries committed at the highest political level to drive through the necessary reforms. Each made the fight against money laundering and terrorist financing a priority and successfully implemented a robust framework of legal, law enforcement and operational measures. Both countries have since become active and valuable members of the FATF, participating in policy development and sharing their national experiences with members of the FATF Global Network.

4.3. Civil Society Influences

- Charity & Security Network (CSN);

- European Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ECNL);

- European Foundation Center (EFC);

- Human Security Collective (HSC).

5. Gaps in the AML Regime

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bruun and Hjejle. 2018. Report on the Non-Resident Portfolio at Danske Bank’s Estonian Branch. Copenhagen: Bruun and Hjejle. [Google Scholar]

- Call, Charles T., and Jeffrey Hallock. 2020. Too Much Success? The Legacy and Lessons of the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3526865 (accessed on 6 November 2020).

- Casey, Eoghan. 2002. Practical Approaches to Recovering Encrypted Digital Evidence. International Journal of Digital Evidence 1: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. 2018. Twelve Candidates Have Been Nominated for the Public Council of International Experts for the Creation of an Anti-Corruption Court. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/corruption/bilateral-activities/ukraine/-/asset_publisher/plqBCeLYiBJQ/content/twelve-candidates-have-been-nominated-for-the-public-council-of-international-experts-for-the-creation-of-an-anti-corruption-court?inheritRedirect=false (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- ERR News. 2021. Denmark Prosecutor Drops All Former Danske CEO Money Laundering Charges. Available online: https://news.err.ee/1608196822/denmark-prosecutor-drops-all-former-danske-ceo-money-laundering-charges (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- FATF. 2019. FATF 30 Years—1989–2019. Paris: FATF. [Google Scholar]

- FATF. 2021a. High-Risk and Other Monitored Jurisdictions. Available online: https://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/high-riskandnon-cooperativejurisdictions/more/more-on-high-risk-and-non-cooperative-jurisdictions.html?hf=10&b=0&s=desc(fatf_releasedate) (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- FATF. 2021b. Who We Are. Available online: https://www.fatf-gafi.org/about/whoweare/ (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- FATF. 2021c. FATF Members and Observers. Available online: https://www.fatf-gafi.org/about/membersandobservers/ (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Fukami, Aya, Radina Stoykova, and Zeno Geradts. 2021. A New Model for Forensic Data Extraction from Encrypted Mobile Devices. Forensic Science International: Digital Investigation 38: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global NPO Coalition on FATF. 2021. About. Available online: https://fatfplatform.org/about-us/ (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Global Witness. 2010. Financial Crime Watchdog’s Chance to Show Its Teeth. Available online: https://cdn2.globalwitness.org/archive/files/import/press_release_at_beginning_of_the_week_final.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- ICIJ. 2017. Offshore Trove Exposes Trump-Russia Links and Piggy Banks of the Wealthiest 1 Percent. Available online: https://www.icij.org/investigations/paradise-papers/paradise-papers-exposes-donald-trump-russia-links-and-piggy-banks-of-the-wealthiest-1-percent/ (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- ICIJ. 2020. Global Banks Defy U.S. Crackdowns by Serving Oligarchs, Criminals and Terrorists: The FinCEN Files Show Trillions in Tainted Dollars Flow Freely through Major Banks, Swamping a Broken Enforcement System. Available online: https://www.icij.org/investigations/fincen-files/global-banks-defy-u-s-crackdowns-by-serving-oligarchs-criminals-and-terrorists/ (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- ICIJ. 2021a. The Panama Papers: Exposing the Rogue Offshore Finance Industry: A Giant Leak of More Than 11.5 Million Financial and Legal Records Exposes a System That Enables Crime, Corruption and Wrongdoing, Hidden by Secretive Offshore Companies. Available online: https://www.icij.org/investigations/panama-papers/ (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- ICIJ. 2021b. Offshore Havens and Hidden Riches of World Leaders and Billionaires Exposed in Unprecedented Leak. Available online: https://www.icij.org/investigations/pandora-papers/global-investigation-tax-havens-offshore/ (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Nance, Mark T. 2018. Re-Thinking FATF: An Experimentalist Interpretation of the Financial Action Task Force. Crime, Law and Social Change 69: 131–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- openDemocracy. 2016. In the Name of Security: When Silencing Active Citizens Creates Even Greater Problems. Available online: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/openglobalrights-openpage/in-name-of-security-when-silencing-active-citizens-creat/ (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- UNIAN. 2018. Poroshenko Signs Law on Establishing High Anti-Corruption Court. Available online: https://www.unian.info/politics/10165775-poroshenko-signs-law-on-establishing-high-anti-corruption-court.html (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- Yeh, Stuart S. 2011a. Corruption and the Rule of Law in Sub-Saharan Africa. African Journal of Legal Studies 4: 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yeh, Stuart S. 2011b. Ending Corruption in Africa through United Nations Inspections. International Affairs 87: 629–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Stuart S. 2012a. Anti-Corruption Inspections: A Missing Element of the IMF/World Bank Agenda? Journal of African Policy Studies 18: 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, Stuart S. 2012b. Is an International Treaty Needed to Fight Corruption and the Narco-Insurgency in Mexico? International Criminal Justice Review 22: 233–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Stuart S. 2013. Why UN Inspections? The Accountability Gap in Sub-Saharan Africa. International Public Policy Review 7: 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, Stuart S. 2014a. Building a Global Institution to Fight Corruption and Address the Roots of Insurgency. International Public Policy Review 8: 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, Stuart S. 2014b. Poverty and the Rule of Law in Africa: A Missing International Actor? Poverty and Public Policy 6: 354–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Stuart S. 2015. Why UN Inspections? Corruption, Accountability, and the Rule of Law. South Carolina Journal of International Law and Business 11: 227–60. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, Stuart S. 2020a. An International Law Approach to End Money Laundering. Journal of International Banking Law and Regulation 35: 148–63. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, Stuart S. 2020b. An International Treaty to Fight Money Laundering. Journal of International Banking Law and Regulation 35: 190–207. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, Stuart S. 2020c. Application of a Model International Treaty to Money Laundering. Journal of International Banking Law and Regulation 35: 443–62. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, Stuart S. 2021a. APUNCAC and the International Anti-Corruption Court (IACC). Laws 10: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Stuart S. 2021b. APUNCAC: An International Convention to Fight Corruption, Money Laundering, and Terrorist Financing. Law and Development Review 14: 633–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabokrytskyy, Ihor. 2020. Transnational Civil Society Influence on Anti-Corruption Courts: Ukraine’s Experience. Global Jurist 20: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Anticorruption Protocol to the United Nations Convention against Corruption (hereinafter APUNCAC), (https://tinyurl.com/y6bkpott, accessed on 22 December 2021). |

| 2 | Regarding access to encrypted communications, see (Casey 2002), Practical Approaches to Recovering Encrypted Digital Evidence. International Journal of Digital Evidence 1: 1–26. (Fukami et al. 2021), A New Model for Forensic Data Extraction from Encrypted Mobile Devices. Forensic Science International: Digital Investigation 38: 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsidi.2021.301169. |

| 3 | See “What is SET?” (https://teaching.shu.ac.uk/aces/rh1/ebiz/what_is_set.htm, accessed on 27 December 2021). The original version of secure electronic transaction technology has now been replaced by 3D SET. |

| 4 | APUNCAC offers each beneficial owner the option of pre-certifying beneficial ownership of all funds sent/received from the corresponding account. When a beneficial owner elects this option, an electronic autoreply flag would be set to “Yes, I certify beneficial ownership of all funds sent/received from my account”. This would permit electronic communication of this information when queried, eliminating delays that might otherwise occur when contacting the beneficial owner to request certification. A beneficial owner who chooses not to certify beneficial ownership of all funds sent/received from his/her account would need to reply to an electronic request for certification. This could be accomplished via a smartphone application, using digital certificate technology and password or 2-factor authentication. However, the point-of-sale transaction could proceed without delay, pending this reply, in the same way that credit card transactions proceed, and are ultimately posted, after all required digital communication is completed (usually within 24 h). If the beneficial owner desires the simplicity and speed of automated certification, he or she would need to elect automatic beneficial ownership certification of all funds sent/received from his/her account (See Figure 1). |

| 5 | “FinCEN” is a unit of the U.S. Treasury Department. “FINCEN” is an international version of FinCEN that would be established by implementing New FATF Recommendation #2. |

| 6 | United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime, 12 December 2000, 2225 U.N.T.S. 277. |

| 7 | United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime, 12 December 2000, 2225 U.N.T.S. 277. |

| 8 | Agreement between the United Nations and the State of Guatemala on the Establishment of an International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala, opened for signature 12 December 2006, 2472 UNTS 47 (entered into force 4 September 2007) [hereinafter CICIG]. |

| 9 | See “What is SET?” (https://teaching.shu.ac.uk/aces/rh1/ebiz/what_is_set.htm, accessed on 27 December 2021). The original version of secure electronic transaction technology has now been replaced by 3D SET. |

| 10 | Senate Perm. Subcomm. on Investigations, Keeping Foreign Corruption Out of the United States: Four Case Histories, Majority and Minority Staff Report, 111th Cong., 2d Sess. (2010). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yeh, S.S. New Financial Action Task Force Recommendations to Fight Corruption and Money Laundering. Laws 2022, 11, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws11010008

Yeh SS. New Financial Action Task Force Recommendations to Fight Corruption and Money Laundering. Laws. 2022; 11(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws11010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleYeh, Stuart S. 2022. "New Financial Action Task Force Recommendations to Fight Corruption and Money Laundering" Laws 11, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws11010008

APA StyleYeh, S. S. (2022). New Financial Action Task Force Recommendations to Fight Corruption and Money Laundering. Laws, 11(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws11010008