Abstract

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission has called upon Canada to engage in a process of reconciliation with the Indigenous peoples of Canada. Child Welfare is a specific focus of their Calls to Action. In this article, we look at the methods in which discontinuing colonization means challenging legal precedents as well as the types of evidence presented. A prime example is the ongoing deference to the Supreme Court of Canada decision in Racine v Woods which imposes Euro-centric understandings of attachment theory, which is further entrenched through the neurobiological view of raising children. There are competing forces observed in the Ontario decision on the Sixties Scoop, Brown v Canada, which has detailed the harm inflicted when colonial focused assimilation is at the heart of child welfare practice. The carillon of change is also heard in a series of decisions from the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal in response to complaints from the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada and the Assembly of First Nations regarding systemic bias in child welfare services for First Nations children living on reserves. Canadian federal legislation Bill C-92, “An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families”, brings in other possible avenues of change. We offer thoughts on manners decolonization might be approached while emphasizing that there is no pan-Indigenous solution. This article has implications for other former colonial countries and their child protection systems.

1. Introduction

In this article, we seek to show how Indigenous child protection cases in Canada are often decided in ways that reflect Euro-centric child protection policy and decision framing that are biased against Indigenous families. We also argue that courts have a role in repairing the current harms inflicted and the harms inflicted from the past. We proceed by looking at the pathways to the current over-representation of Indigenous children in care. We then consider legal decisions that act as hallmarks around the role of child protection in the lives of Indigenous peoples. The first is Racine v Wood (Racine 1983), which is a Supreme Court of Canada decision that laid the foundation for the Western theories around attachment and bonding to be seen as paramount to cultural considerations. Brown v Canada (Brown 2017) is next considered as showing not only the duty of care but also the harm inflicted by the failure of to fulfill its duty of care to Indigenous children. We then turn to the series of decisions made by the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (CHRT) related to complaints by the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society and the Assembly of First Nations. Finally, we will look at an Alberta provincial court decision, URM (URM 2018) and its appeal in the Court of Queen’s Bench (Alberta) (SM 2019) to show the challenges faced by lower courts in trying to decide these cases. The relevance of this approach is to show how child protection continues to engage in over-surveillance of Indigenous peoples and thus the over representation of Indigenous children in care, which we relate to the lack of understanding of Indigenous methods of knowing and being (Whitcomb 2019). This is further complicated by structural inequality resulting in poverty, housing insecurity and deprivations in the social determinants of health (Blackstock et al. 2005). An ethical space needs to be opened up where the Euro-centric Canadian society can come to listen and understand Indigenous knowledge, codes of conduct, moral views, cultural practices and familial practices which would allow the breaking of the schism that exists between us (Ermine 2015).

2. Social Location of the Authors

As is important in a Canadian context and Indigenous studies, providing a social location of the authors is important so that the relationship between the work and the place of Indigenous peoples is clear.

Peter Choate is a white Canadian settler who is Professor of Social Work at Mount Royal University, Calgary, Canada. Roy Bear Chief is an Elder with the Siksika First Nation. He is also Espoom Taah at Mount Royal University. Desi Lindstrom is a “Sixties Scoop” survivor who is Anishnaabe. Brandy CrazyBull grew up in the care of child protection and has recently learned her Indigenous name. She is a member of the Kainai First Nation. Desi Lindstrom and Brandy CrazyBull are currently social work students at the University of Calgary.

3. Methodology

This paper is an analysis of case law and secondary literature. We sought to explore the intersection between the practice of placing Indigenous children in the child welfare system with non-Indigenous families and the methods in which legal decision-making supports this.

4. The Intersection of Child Welfare and Indigenous Peoples

Indigenous children have been and continue to be overrepresented in the child welfare systems of Canada (Sinha et al. 2011). This has been true for decades with Dr. Cindy Blackstock of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada suggesting that child welfare became the new residential schools (Blackstock 2016, 2007). As Sinha et al. (2011) points out, data from the various incidence studies of child welfare cases in Canada shows that, “For every 1000 First Nations children living in the geographic areas served by sampled agencies, there were 140.6 child maltreatment-related investigations in 2008; for every 1000 non-Indigenous children living in the geographic areas served by sampled agencies, there were 33.5 investigations in 2008” (pp. xiv–xv). The rate of investigations involving First Nations children was reported in their work to be 4.2 times greater than the rate for non-Indigenous investigations. More recent data from the Canadian province of Ontario indicates that over-representation is an ongoing concern (Crowe et al. 2021). These authors add that this must be understood as follows, “differences between First Nations children and non-Indigenous children must be understood within the context of colonialism and the associated legacy of trauma (Crowe et al. 2021, p. ii).

There is little doubt that child protection systems in Canada are racially biased against Indigenous populations. This is outlined in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report (TRC 2015a) as well as other inquiries such as the Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC 2018). The racism is also experienced by racialized child welfare workers rendering it difficult to bring a cultural lens into their work (Gosine and Pon 2011). The TRC (2015a) shows the linkage between child welfare involvement with Indigenous families and, as they frame it, cultural genocide from colonization and assimilation efforts, such as the Indian Residential Schools (IRS) and the Sixties Scoop.

Within racism, there are underlying structural assumptions. For example, the definitions of family and good enough parenting are drawn from Euro-centric belief systems (Choate et al. 2020a). This is linked to the historical belief that Indigenous parenting systems, within collectivistic child rearing practices rooted in culture, were sub-standard (Lindstrom and Choate 2017). If that assumption is taken away and the true capacity of Indigenous caring systems is examined, then a child can be raised very effectively within culturally based caregiving (Makokis et al. 2020; Bourassa et al. 2017). Furthermore, as the TRC (2015a) points out, Indigenous parenting has been deprived of support through colonial policies and programs where the elimination of the Indigenous cultures was the goal.

First Nations child residents on reserves and in the Yukon Territory of Canada have been subject to prejudicial funding levels for child welfare services (Blackstock et al. 2005) (along with other services such as education (FNEC 2009) and other necessary supports such as clean drinking water (Bradford et al. 2016)) at rates that are much lower than services provided through provincial and territorial funding. This is not so for Métis or Inuit children whose services are funded at the provincial and territorial levels (NCCIH 2017). Some of this inequity may change as a result of Canadian federal legislation Bill C-92, “Act Respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis Children, Youth and Families Act (Bill C-92)”. This came into effect on 1 January 2020, but has yet to be properly funded. At the time of this writing, Canada and the province of Saskatchewan have entered into an agreement with one First Nation, the Cowessess First Nation, which gives the Nation power over decision making for their children who may need prevention and protection services. That agreement came with capital funding. However, it also sets up a precedent of funding formulation that may be negotiated on a nation-by-nation basis as opposed to an established formula. Nonetheless, further agreements between the Government of Canada, provinces and First Nations are expected according to Prime Minister Trudeau (verbal comments by Prime Minister on 6 July 2021 at signing ceremony).

Turpel-Lafond (2020) points out that the Bill C-92 legislation does move forward with establishing national standards for Indigenous child welfare, which brings immediate change along with a process that will support further steps. If funding models are not developed to end economic disparity in child welfare and the public services such as addictions, housing and poverty remediation, which are linked to the over-representation of children in care, then structural inequity will be sustained. However, even with the funding issues unresolved, C-92’s national standards override provincial standards for the protection of Indigenous children unless those provincial standards are greater (Friedland and Lightning-Earl 2020). This is, at a minimum, changing the ways in which cases covered by C-92 might be decided by the courts. This will be discussed later in the paper.

4.1. Brief History of Indigenous Child Protection Removals

There have been three significant periods of removal of First Nations children from their families and communities with the goal of assimilating Indigenous children into Euro-centric colonial society. The first is the period of Indian Residential Schools (IRS) from 1831–1996 (TRC 2015b). The last school to close was the Gordon Residential School in Saskatchewan which opened in 1888 (Niessen 2017). Approximately 150,000 children went to the schools, which were focused on breaking the link between the child and the culture and family (TRC 2015b; Union of Ontario Indians 2013). The next period was the Sixties Scoop which saw about 20,000 Indigenous children removed from their home and community to be placed in non-Indigenous foster and adoptive care (Johnston 1983). The term Sixties Scoop was coined by Patrick Johnston who is the author of the 1983 report, Native Child and the Child Welfare System (Johnston 1983). It refers to the mass removal of Indigenous children from their families into the child welfare system and in most cases without the consent of the families or bands. It should be remembered that child welfare also used the IRS as placements (Blackstock 2007).

The third period is known as the Millennial Scoop which was seen as simply the continuation of the Sixties Scoop (McKay 2018). This is related to the increased and ongoing rates of high representation of Indigenous children in the care of the Canadian child welfare systems (Blackstock 2007). Since the Sixties Scoop, the representation has grown and remains high. Dr. Raven Sinclair has shown that the child removal system in Canada remains racially structured (Sinclair 2016; Trocmé et al. 2004). Indeed, the colonialism of child welfare has really never been disrupted (McKenzie et al. 2016). Theory, practice, definitions and methodology remain rooted in Euro-centric understandings of parenting, family and best interest (Lindstrom and Choate 2017).

The Canadian 2016 Census noted that 7.7% of children under the age 14 years and under in Canada are Indigenous, while 52.2% of children in care under the age of 14 are Indigenous (Statistics Canada 2016).

4.2. The Question of Race

Boyd and Dhaliwal (2015) identifies race as deeply relevant to the development of the child and identity. The TRC (2015a) sees that race has been determinative in that the cultural parenting of Indigenous families has been seen as not sufficient when Euro-centric standards are imposed. Race based decision making has been avoidant of the real needs of the child to be connected to and raised within their own culture (Harnett and Featherstone 2020). This has resulted in direct harm to children (Mosher and Hewitt 2018).

However, in looking at race with respect to child custody matters, Boyd and Dhaliwal refer to a Supreme Court of Canada decision quoting Bastarache J. in writing for the Court, “race is not a determinative factor and its importance will depend greatly on the facts.” (Van de Perre 2001). Boyd and Dhaliwal add that Bastarache saw race as one of the factors to be considered regarding the disposition of a child as opposed to a superior or determinative factor (Boyd and Dhaliwal 2015). Racine v. Woods (Racine 1983), which we will examine later in this paper, determined that race was overshadowed by a child’s bond to another caregiver even when that person is not part of the child’s cultural identity.

Indigenous peoples in Canada have been subjected to cultural genocide (Mako 2012) as documented in the national reports of the TRC (2015a, 2015b) and the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP 1996), as well as provincial reports such as the Kimelman Report (Kimelman 1985) along with multiple reports from child and youth advocates across Canada (CYAA 2016, 2017a, 2017b, 2018; MACY 2016, 2018; RCY 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018; SA 2016a, 2016b) as well as Hughes (1991) and Hughes (2013). All have failed to yield a downward trend in Indigenous children coming into and staying in child protection care. The reports consistently point to ongoing deprivations in services and supports along with linkages to the need for decision making rooted in Indigenous methods of knowing and parenting. The historical traumas are now well documented as existing not only in the first occurring generations but also through inter-generational transmission resulting in the greater presence of mental health and related issues in subsequent generations. This is not well considered in child protection courts as described by Mosoff et al. (2017).

“Similarly, the experience of Indigenous mothers reveals a history of colonial and racist processes of regulation of Indigenous families. Yet child protection law tends to erase this history through the supposedly neutral application of the best interest of the child standard, the key legal principle in child welfare”(pp. 438–39).

As these authors note, this places mothers, in particular, in opposition to the child as it relies on the dyadic notion of mother and child in a relationship weighed down by mental health and absent of the communal and community system of parenting common to most Indigenous nations. Mosoff et al. (2017) conclude that judges fail to consider inter-generational issues and blame mothers for the circumstances they find themselves in lacking support from the state which might serve to mitigate the intergenerational effects. They see the courts as particularly likely to separate vulnerable mothers from children with special needs. We argue that this is a heightened reality for Indigenous mothers and children.

4.3. Pathway of Harm

The reports noted above (TRC 2015a; RCAP 1996) have shown that assimilation through separation and fragmentation was at the heart of the IRS, the Sixties Scoop and the continuing over representation of Indigenous children in care. The goal of assimilation could not be achieved if Indigenous children were kept within their culture and exposed to Indigenous world views. Rather, the notion of IRS was separation and indoctrination into Euro-centric culture rooted in Christianity. Race became a determinative factor in who was good enough which would begin to pervade the child protection world. If a person was Indigenous, they were not seen as appropriate to raise their child and this a theme that will be observed in child protection from its earliest entry into the lives of Indigenous people (Kimelman 1985).

Duncan Campbell Scott was Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932. In 1920, he proposed making attendance at IRS mandatory. In proposing an amendment to the Indian Act, Scott stated the following.

“I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that this country ought to continually protect a class of people who are able to stand alone. That is my whole point. Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic, and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department, that is the whole object of this Bill” D.C. Scott, 1920.(Titley 1986, p. 50)

Education was not the goal of IRS but rather assimilation (Wattman 2016). The harm, abuse, deprivation and isolation of the IRS began the inter-generational devaluation of Indigenous childcare but also fragmented the child’s connection to Indigenous identity. Scott would later acknowledge the harm inflicted, although he would not take steps in his tenure to ameliorate the damage (Wattman 2016).

When children came back to their communities after IRS,1 many no longer knew their cultural ways and did not speak the language. They were now strangers whose internal identity was neither Indigenous nor white—a theme that becomes repeated as children continue to be removed from community and culture with legacies of long-term harm (Barnes and Josefowitz 2019). This is sometimes referred to as ‘whitestreaming’ children away from their identity (Grande 2013) and creates losses that are challenging to overcome even when, as an adult, there is reconnection to their culture (Choate et al. 2020a). One author (DS) is a Sixties Scoop survivor who notes, “Because today I go back, and I don’t know these people and they don’t know me. I’ve been back within that family system for over 20 years now, and they still don’t know me.” Another author (BC) grew up in foster care and was from the “millennium scoop”. She describes the identity conflict experienced even when connected to her family and culture in growing up in a white home.

“So, from the beginning physically-wise I could see that we were living with white people, which was obviously different from every place I had lived before with aunts and uncles, grandparents and stuff. Everybody else is Indigenous and brown, so it clearly made a difference to me when I’m placed with a bunch of white people. But at the same time, it wasn’t like I was totally disconnected from my family because I would still go on visits with them. But at that time, it was like when I was in the home I would try to fit in and belong instead of trying to be different and like an outsider and this, I don’t know. I would try to belong in that family, so it’s kind of like I was wearing a mask at home, but when I would go and visit with my biological family with my mom or my dad or my grandparents it was kind of like I would take that mask off and I’m back to where I started”.

Yet, as BC notes, “Colonialism has done me harm, I still came out strong and with education through the process that was made to make me fail”.

Damage is not just inflicted from children being removed but also from the fear of government officials who could remove a child at will, separating families from utilizing their own support systems. The damage is not restricted to the direct victims, which consists of those actually removed, but also to the communities, clans and societies. The harm transmits across generations creating inter-generational traumas, which is an effect now well documented in various traumatized populations. A body of research has shown that intergenerational trauma from assimilation and colonization can be observed across generations (Brown-Rice 2013; Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart et al. 2011).

In a research project (Choate et al. 2020b), one Indigenous academic participant noted that the removal to IRS came to be known as the ‘boogeyman’ who could grab you. The ‘boogeyman’ was white, powerful and could muster the resources of the police to overcome resistance. Relationships and trust by Indigenous peoples towards the dominant white population were destroyed and remain heavily damaged to date. The relationship remains one where the dominant society is still in control of the destiny of Indigenous children and, therefore, remains power and domination focused.

5. The Legal Cases

There are four cases that help to illustrate the concerns regarding the methods in which Indigenous family, parenting and culture are considered by the courts and which link the historical fashion in which Indigenous peoples have been framed in Canadian society: Brown v Canada (Brown 2017); Racine v Woods (Racine 1983), First Nations Child and Family Caring Society and Assembly of First Nations and Canadian Human Rights Commission v Canada (CHRT); and URM (Alberta) (URM 2018) and the appeal that followed, SM v Alberta (SM 2019).

5.1. Brown v Canada

Brown v Canada (Brown 2017) was a class action lawsuit based on the 16,000 Aboriginal children apprehended by the Province of Ontario in the period from 1 December 1965 to 31 December 1984. There was an agreement between Canada and Ontario in 1965 that required Canada to consult and “whether Canada can be found liable in law for the class members’ loss of Indigenous identity after they were placed in non-Indigenous foster and adoptive homes” (Brown 2017, para. 10). The court, in answering that question, did not find a fiduciary duty but a common law duty, the failure of which resulted in harm.

[6] There is also no dispute about the fact that great harm was done. The “scooped” children lost contact with their families. They lost their aboriginal language, culture, and identity. Neither the children nor their foster or adoptive parents were given information about the children’s aboriginal heritage or about the various educational and other benefits that they were entitled to receive. The removed children vanished “with scarcely a trace.” As a former Chief of the Chippewas Nawash put it: “[i]t was a tragedy. They just disappeared.”

[7] The impact on the removed aboriginal children has been described as “horrendous, destructive, devastating and tragic.” The uncontroverted evidence of the plaintiff’s experts is that the loss of their aboriginal identity left the children fundamentally disoriented, with a reduced ability to lead healthy and fulfilling lives. The loss of aboriginal identity resulted in psychiatric disorders, substance abuse, unemployment, violence and numerous suicides.

The consultation required in the 1965 agreement did not occur and is related to the harm suffered. The evidence before the court indicated that, if consulted, Indigenous communities would have taken steps to preserve connection and identity. Quite importantly, the Court determined that, at the time, Canada knew that the actions of separating children from culture would be harmful (Brown 2017, para. 52) Thus, Canada knew it had and, by inference, continues to have a common law duty to prevent loss of identity. We will argue that common law duty is not being respected in current child welfare practice.

5.2. Racine v Woods

Leticia Grace Woods was born on 4 September 1976 in Manitoba to her Indigenous mother Linda Woods, who had a history of alcohol problems. Leticia’s biological father is unknown. Leticia was in kinship care before she was apprehended by child welfare authorities in Manitoba at the age of 6 weeks. She became a ward of child welfare for a one-year term, which was extended by an additional six months. Leticia was placed in the foster home of Sandra and Lorne Ransom who divorced later that year. Sandra entered a new relationship with Allan Racine. Leticia remained in their care until the wardship expired a year later. Leticia was returned to her mother. After the return to her mother, the Racines visited twice. They were permitted to take Leticia home the second time with Mrs. Woods believing that to be temporary while the Racines believed that this was a permanent placement and began the process of adoption. Five weeks later Mrs. Woods arrived at the Racine’s home stating she was moving and wished to place Leticia in kinship care. The Racines refused to relinquish Leticia to her mother. The Racines would ultimately be granted adoption of Leticia. The case would end up before the Supreme Court which would affirm the adoption (Choate et al. 2019)

Madame Justice Wilson, in writing for the Court, began the decision stating the following.

“The law no longer treats children as the property of those who gave them birth but focuses on what is in their best interests. In determining the best interests of the child, the significance of cultural background and heritage as opposed to bonding abates over time: the’ closer the bond that develops with the prospective adoptive parents the less important the racial element becomes”.(Racine 1983, p. 174)

The Court was not blind to the cultural issues but felt that the Racines constituted the position of “psychological parent” which in combination with sensitivity by the Racines to Indigenous issues served the best interest of Leticia.

“Leticia is apparently a well-adjusted child of average intelligence, attractive and healthy, does well in school, attends Sunday School and was baptized in the church the Racine family attends. She knows that Sandra Racine is not her natural mother, that Mrs. Woods is her natural mother, and that she is a native Indian. She knows that Allan Racine is not her natural father and that he is a Metis. This has all been explained to her by the Racines who have encouraged her to be proud of her Indian culture and heritage. None of this seems to have presented any problem for her thus far. She is now seven years old and the expert witnesses agree that the Racines are her “psychological parents”.(Racine 1983, p. 177)

The adoption broke down resulting in Leticia being in group care through most of her teenage years. Leticia recently noted, “I had no identity, nobody to connect with. I always felt shame, I asked myself, ‘why did I have to be this colour?’ I’d look in the mirror and say, ‘I hate you’.” (Sixties 2018, p. 1) Leticia later would reconnect with her mother.

When Racine (1983) is considered in combination with Brown (2017), we are faced with the combined result that caring for Indigenous identity and culture has not been seen as having paramountcy within child protection practice. Racine (1983) identifies that child protection decisions can and should be based within Euro-centric understandings of family and, by implication, diminishes the world views of Indigenous peoples. However, Richard (2007) and Sinclair (2007a, 2007b) point out that children apparently bonded to the non-Indigenous caregiver will more often than not fail to maintain that relationship over time, as has happened with Leticia. Yet, Racine (1983) remains a leading case. A recent search of the Canadian Legal Information (CanLii) database shows that the case has been cited over 600 times and is typically used as a supportive precedent. An example is M.M. v T.B, (MM 2017) where a decision of the British Columbia Court of Appeal noted that for Racine (1983), “that decision remains good law” (MM 2017, para. 97).

5.3. First Nations Child and Family Caring Society and Assembly of First Nations and Canadian Human Rights Commission V Canada

This series of 21 cases (the full list is in the references) involving two overarching matters. The first related to the underfunding of child protection services on reserves (protected lands given over to First Nations peoples) at a rate of about 30% lower than for children being served by provincially funded services. On the reserve, child protection falls under federal jurisdiction while, off reserve, child protection falls under provincial or territorial government jurisdiction. The second issue referred to the failure to properly fund services under what is known as Jordan’s Principle. The CHRT (2017a) defined this principle as the following.

“Jordan’s Principle2 provides that where a government service is available to all other children, but a jurisdictional dispute regarding services to a First Nations child arises between Canada, a province, a territory, or between government departments, the government department of first contact pays for the service and can seek reimbursement from the other government or department after the child has received the service. It is a child-first principle meant to prevent First Nations children from being denied essential public services or experiencing delays in receiving them. On 12 December 2007, the House of Commons unanimously passed a motion that the government should immediately adopt a child-first principle, based on Jordan’s Principle, to resolve jurisdictional disputes involving the care of First Nations children”.(para. 2)

In 2007, the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society and the Assembly of First Nations alleged Canada’s underfunded provision of First Nations child and family services and its failure to implement a child first principle, Jordan’s Principle, were discriminatory on the prohibited grounds of race and national ethnic origin pursuant to the Canadian Human Rights Act. The Government of Canada took a very narrow view of what was to be addressed which resulted in a series of further decisions by the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (CHRT). The most recent decision (CHRT 2020a) has again expanded the boundaries of coverage for Jordan’s Principle to include those who are recognized by their nation and those with a parent who possesses status under the Indian Act (Indian) along with those who qualify for that status under an amendment to the Indian Act through Bill S-3, which removed gender-based inequities for status registration (Descheneaux 2015).3 As of this writing, however, that decision is under appeal.

An important parallel decision occurred in 2013, which known as the Pictou Landing Decision (2013). It determined that Jordan’s Principle could include services for First Nations children living off reserve, which served to expand the program. Justice Mandamen stated at para 86 that Jordan’s Principle “was not to be read narrowly”. At para 116 she noted that that Jordan’s Principle “requires complimentary social or health services be legally available to persons off reserve” (Pictou 2013).

In January 2016, the CHRT substantiated the complaint of discrimination, ordering Canada to immediately cease its discriminatory conduct (CHRT 2016d). Canada took no action on Jordan’s Principle until it unilaterally announced the Jordan’s Principle Initative in July 2016. In this approach, Canada adopted a definition of Jordan’s Principle that limited it to health and social services for children with critical short-term illnesses or multiple disabilities. The Caring Society and other parties to the CHRT disagreed with this definition and approach and brought non-compliance proceedings against Canada in December 2016 (CHRT 2017a). As noted above, the dispute continues and the CHRT remains seized of the matter.

This CHRT complaint is a complex case with roots as far back as 2005 (Loxley 2005). Bezanson succinctly notes, “In this landmark case, the CHRT found that the Canadian government had discriminated against First Nations children on reserve in its provision of funding for child welfare and certain other services” (Bezanson 2018, p. 152). These other services include health and education, in particular. Metallic adds that the Tribunal decision “requires that First Nations people receive child and family services that meet “their cultural, historical and geographical needs and circumstances”. The Tribunal did not qualify that this requirement relates only to funding; indeed, it suggested that First Nations child and family services, as a whole, and inclusive of funding must meet this standard” (Emphasis in original) (Metallic 2018, p. 6). Without the financial integration of resources with the actual circumstances of the child in the community along with cultural needs, Jordan’s Principle cannot achieve effective delivery. Metallic goes on to say, “that, as a matter of human rights: (1) First Nations are entitled to child and family services that meet their cultural, historical, and geographical needs and circumstances; and (2) such services cannot be assimilative in design or effect—firmly ground the argument that First Nations have a human right to self-government over child and family services” (Metallic 2018, p. 7).

This CHRT decision (CHRT 2016d) drives towards the notion that Canada, the provinces and the territories cannot act separately from the Indigenous peoples of Canada nor can they determine how child protection is to be conducted. Bezanson adds, “The Tribunal concluded that ‘these adverse impacts perpetuate the historical disadvantage and trauma suffered by Indigenous people, in particular as a result of the Residential Schools system’” (Bezanson 2018, p. 156). This is affirmed by the CHRT (CHRT 2020b), which reinforced an earlier compensation decision (CHRT 2019a). In the latter decision the CHRT stated the following.

“The Panel believes that the unnecessary removal of children from your homes, families and communities qualifies as a worst-case scenario […] and, a breach of your fundamental human rights […] that this case of racial discrimination is one of the worst possible cases warranting maximum awards […] The Tribunal was clear from the beginning of its Decision that the Federal First Nations child welfare program is negatively impacting First Nations children and families it undertook to serve and protect. The gaps and adverse effects are a result of a colonial system that elected to base its model on a financial funding model and authorities dividing services into separate programs without proper coordination or funding and was not based on First Nations children and families’ real needs and substantive equality […]”(CHRT 2020a, para. 13).

These decisions highlight the paternalistic methods in which child welfare has approached issues with Indigenous peoples. The cultural understanding of raising a child has been taken out of the conversation to be replaced with Euro-centric universal views (Choate 2019). Brown (2017) shows the historical harm, Racine (1983) shows its application and the various CHRT decisions show that solutions must lie within the culture not external to it.

5.4. URM

This Alberta Provincial Court (URM 2018) decision illustrates problems of grappling with how to make the issues and connections of Indigenous identity work in the lives of children. The decision of the lower court was affirmed in an appeal (SM 2019). The original and appeal decisions illustrate how historical thinking in courts will require challenge if the Brown (2017) and CHRT decisions are to be instruments of change.

URM (2018) focuses upon the long-term placement of two Indigenous girls who have been made permanent guardians of the Director of Child Welfare in Alberta. There were two competing applicants to adopt the children; the long-term foster parents who live in an urban area and Indigenous kin who live on a rural reserve. One child is noted to have high medical needs. These young children have essentially spent their lives in the non-Indigenous foster home. At the time of the decision, both children were deemed eligible for status registration under the Indian Act but that had not occurred. The trial judge adopted the thinking of Racine by placing the greater emphasis on the question of best interest of the child. The Court saw that question, in the form of attachment to non-Indigenous caregivers, as distinct from and superior to the question of sustaining the child within culture. The Court added a particularly interesting addition by observing that, “The focus must be on the biological tie as a meaningful and positive force in the life of the child, and not the child’s potential to be a meaningful and positive force in the life of those family members, or that family group, or that Nation” (para. 116). The Court saw as determinative a possible harm arising from an attachment disruption.

The trial judge concluded the following.

[138] To be absolutely clear, I reject as unsustainable or insupportable that the factor of maintaining Indigenous heritage is sufficient reason to ignore attachment theory. This position amounts to prioritizing the preservation of Indigenous heritage at the expense of all other factors, including the established attachment relationship between the children and the Foster Parents. Such an approach is not supported under a best interests analysis using, for example, the factors listed in the FLA (s. 18) or any provision in the CYFEA(See RP at para. 7) (URM 2018).

When faced with the fate of two children, the trial judges balanced best interest, which we argue is not a culturally applied term against culture and existing relationships. Cases of this nature force either/or decision making. The appeal upheld the lower court decision (SM 2019). While not specifically affirming Racine, the court noted the following at para. 282.

“Courts are not required to and should not prioritize Indigenous culture to the expense of all other factors. The paramount consideration is the best interests of the Children and as the Supreme Court has stated that all factors relating to the best interests of the child test must be considered pragmatically.”(SM 2019)

This results in question of how Indigenous identity is to be weighed if the TRC (2015a) recommendations and the intent of Bill C-92 are to be implemented.

6. Analysis and Commentary

6.1. Historical Context

Brown (2017) helps us to observe the intersection of the role of the courts with respect to the impacts of colonialism and assimilation policies over time and, as the CHRT notes in its 2020 decision, the body of politics that is responsible for the outcome. CHRT (2020a, 2020b) shows that systems can become so incorporated into racial bias that it can be blinded to the damage or diminishes the supposed impact. Some might try to argue that Brown (2017) and CHRT refer to a colonial period and that we are now moving to or are in a post-colonial state. Bonds and Inwood (2016) make two crucial points that belie the notion of post-colonialism. In Canada and other countries subject to imperial expansion, the goals were to occupy and take ownership of the lands utilizing the doctrine of terra nullis (or land belonging to nobody which denied Indigenous peoples ownership of lands occupied by them for centuries). From this, the occupiers then moved to ingratiate, assimilate and in some cases kill the prior native owners of the lands. Bonds and Inwood (2016) go on to note that this continues through white domination of systems, definitions, services, law and judicial application, amongst other day to day forms of control such as over surveillance of Indigenous peoples. They go so far as to say this is the true meaning of “white supremacy”. They add, “A focus on white supremacy thus highlights both the social condition of whiteness, including the unearned assets afforded to white people, as well the processes, structures and historical foundations upon which these privileges rest” (Bonds and Inwood 2016, p. 720).

The historical context might well ask the question of whether Brown or Racine would have occurred had Canada seen that Indigenous cultures were worth preserving and offered children parenting that was both culturally rooted and in the best interests of the Indigenous child. If that preservation had occurred, then both decisions would have been based upon a very different standard, that is, being an Indigenous one.

6.2. Intersectionality

The American legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw (1991) has coined the term intersectionality, which we argue is at the core of how cases must be considered and how Indigenous child welfare is addressed. Crenshaw, by looking at black women in the USA, saw intersectionality as the manners stories were told to and interpreted by courts. The methods in which history, race, discrimination and bias operate compound the factors making it necessary to observe them not from a factor-by-factor analysis but to observe the total impact of systems operating from a racially biased perspective. CHRT links together assimilation, colonialism, paternalism, racially and discriminatory practices and legislation that systematizes the probability of adverse outcomes for Indigenous children. CHRT adds dimensions that demand moving beyond the intersections of historical and systemic oppression to address achieving substantive equality. This requires both the recognition of the historical harm while recognizing that targeted or specific efforts must be taken to achieve equity for a specific group, First Nations as well as other Indigenous populations. CHRT decisions along with TRC (2015a) affirm the intersectional nature of social, legal, historical, policy and practice elements of child protection as a structurally racialized system.

For our purposes, substantive equality should also include the deconstructing of colonial and euro-centric practices and beliefs that have been used to adversely damage Indigenous populations including separating families and communities through child protection legislation, policy and practice. It also demands pathways of change alleviating the harmful practices and, as Bill C-92 has begun to execute, ensure the power of child protection belongs not to the dominant society but to the Indigenous peoples of Canada with respect to their own children. This means that judicial decisions bound in non-Indigenous methods of knowing need to be interrogated to ensure colonialism is not extended.

6.3. Best Interest of the Child

All Canadian child protection legislation refers to the Best Interest of the Child test. The newly passed Bill C-92 also includes this in s. 9 (1) but puts it into an Indigenous context. In terms of this paper, we see the importance in the application to Indigenous children specifically.

This places the needs of the child at the center of the case but what do we really mean by the term as it might relate to an Indigenous child involved with child protection? It is not our intention to extensively review the debates on best interest, but rather to note that its developments and applications have resulted from a basis in Euro-centric understanding. It often combines with the notion of the “psychological parent”, which Justice Wilson relied upon as a factor in determining the best interest for Leticia (Racine 1983). What then is the evidence of the construct of “psychological parent”? The notion arose from the work of Goldstein et al. (1996, 1973). It was first postulated in the 1970’s and later updated in 1996. It is a concept that has been widely accepted in North American courts relying upon the notion that a new person can step into the role of parent without biological linkage and become the “psychological parent”. If the concept is to be accepted, then it buttresses attachment theory by showing that the child can form new and significant attachment relationships. On the other hand, it is vital to note that it is a theoretical concept that has not been subject to significant validation or definitional research, although a search of the Canadian Legal Institute database search shows that it is a commonly used construct.

Bill C-92 moves the notion of “best interest” away from an interpretation that diminishes the Indigenous identity of a child and rather places it in direct connection. Such a view steps away from Racine (1983) and into an argument that the rights of an Indigenous child are directly connected to Indigenous identity, which is contrary to Racine (1983).

Bill C-92 goes further by adding two other principles that are considered along with Best Interest. They are Cultural Continuity as observed in s. 9 (2) and Substantive Equality, which is observed in s. 9 (3). In our view, this is a significant shift that no longer leaves Best Interest in a primacy position separate from culture. This law also sets national standards. Provinces and territories, should they continue to be the agencies delivering services, cannot go below these national standards. They are now law. S.10 of Bill C-92 sets eight factors that consider the “Best Interests of Indigenous Child” to specifically direct attention to Indigenous children (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Eight factors to be considered regarding the Nest Interest of an Indigenous Child as per s.10 of Bill C-92.

In the case of SH (2020), the Court saw best interest as including continuity of care within an existing placement that was not with a biological parent although the father had now become available. Part of the decision rested on the child’s very significant connection to her Klahoose and Homalco Indiegnous cultures since 13 months of age such that she was able to speak the language and was competent in traditional songs and dances. She had a strong relationship with her grandfather who also taught her culturally.

6.4. Expert Evidence

Courts are faced with a reality that current assessments, theory and evidence are rooted in Euro-centric understanding of key concepts including how family is defined: good enough parenting; tools for assessing and drawing conclusions; pathologizing data that fails to consider inter-generational trauma; knowledge and expertise of elders and the world views about the place and role of children (Choate et al. 2020a).

Ewart v Canada (Ewert 2018) affirmed that assessment tools that are not culturally valid can create bias. We contend that such bias is rife in child protection (Choate and McKenzie 2015). Lindstrom and Choate (2017) have shown such bias in the definition of family, childcare, parenting standards and methodology for assessing parental capacity. Given that, the bias operates against parents and sets up significant barriers for an Indigenous parent to be deemed appropriate to raise their own child. That bias extends further into the question of who is an acceptable alternative caregiver with most children being placed out of culture. This is inconsistent with Bill C-92.

We would go further by suggesting that those who offer testimony on “best interest” must now offer it from an Indigenous understanding, including the use of assessment methodology that uses Indigenous knowledge rather than the Eurocentric understandings of good enough parenting (Choate and Lindstrom 2018). This raises the question of whether an “expert” using colonial assessment theory and tools can be so qualified in a case involving an Indigenous child. An assessor lacking Indigenous expertise may not be a properly qualified expert as outlined in R. v Mohan (Mohan 1994) and White Burgess (2015). The expert must also be independent and impartial. An expert cannot be seen as impartial when using methods, tools and knowledge that are biased and will have a propensity to sustain colonial approaches which bias towards a negative view of an Indigenous parent.

In terms of traditional knowledge keepers as experts, Elders represent competent knowledge holders of Indigenous traditions, values and morality as well as the place of children. This is typically represented in oral traditions in which Elders pass on their teachings and stories. Courts struggle with this evidence although as Craft (2013) has shown, courts can make a place for oral histories; however, this has often been more associated with asserting territorial land claims than with child protection matters.

To our knowledge, this has not been tested in any significant child protection matters although it is through Elder knowledge that the history and rights around the raising of a child are transmitted. The use of Elder testimony is not specifically addressed in Bill C-92, but the items in Table 1 could draw upon the specific knowledge of an Indigenous tradition relative to the child. It would be through such knowledge that the courts could avoid using Bill C-92 tests in a pan-Indigenous manner. This would be consistent with the wording of s. 10 which speaks of “the child”.

7. Conclusions

In this paper we have discussed the implications of culture having very specific meanings within a lineage of peoples who have built practices, understandings, relationships and systems that reflect who they are and how their children are to be nurtured and raised. In our work, we have seen, however, that it is the Euro-centric understandings of family, parenting, child development and related theories that have come to represent the basis upon which child protection makes decisions about good enough parenting. Thus, our first and most prominent challenge is to deconstruct definitions that are applied to populations for which they are not appropriate and develop new approaches that are. For example, constructing parenting assessment would look very different from present approaches since “good enough” would have collective as opposed to nuclear connections to determine who is within the caregiving system. Indeed, assessment for the courts would need to draw upon the caregiving system for an Indigenous child as opposed to the dyadic parent–child relationship which is common in European traditions. This means that elements such as the caregiving environment, the manner and goals of raising a child, the meaning of identity, attachment and psychological well-being would be subject to Indigenous worldviews. Gladue (1999) reports within the criminal system are examples of how assessment can be constructed differently by taking into consideration the history of colonization and assimilation as contemplated by the TRC (2015a). This paper has argued that the courts continue to have a role in extending colonial understandings of family and caring for a child but also a role in questioning evidence that does so. In addition, there is the recognition that the courts offer venues for change as well as compensation.

Brown (2017) illustrates the failure of cross-cultural adoptions on a large scale and the necessity for compensation for harm inflicted. Bill C-92 creates priority of placement within culture through national standards starting with parents as the first ranked order. Following that, in the order of priority are other family members, other community members, other Indigenous options and then, lastly, other possible placements. Assessment of caregiving must now give attention to these options while also considering placement with or near siblings as well as the customs and traditions of the Indigenous community which include custom adoptions.

Other research affirms that Indigenous adoptions and placements into nonindigenous homes remain generally unsuccessful (McKenzie et al. 2016; Boyd and Dhaliwal 2015). Indeed, the personal stories of two authors (DL and BC) show both the failure and the ongoing lifelong challenges that occur. An example is a quote from author BC noting that “I was born in 1995 but only learned my (Indigenous) name in 2019.” It is now clear that Indigenous peoples are not going to vacate their space in favor of Euro-centric peoples, cultures or understandings. Indigenous children have the right to be Indigenous. This results in asking what value, then, is Canada placing on these rights and upon the children who own these rights?

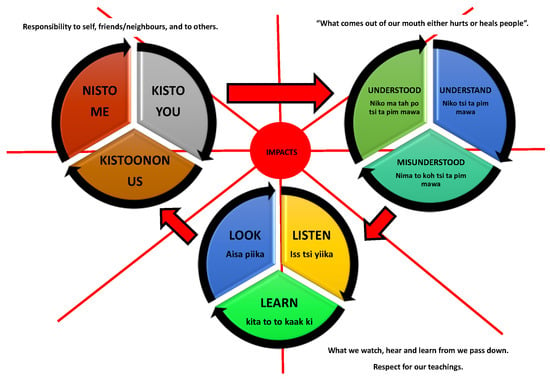

The answer lies in having courts presented with data that does not extend colonial understandings. This requires the cessation of Euro-centric approaches acting as the basis upon which expectations are defined and constructed. This demands a re-examination of knowledge, beliefs and values as observed in Figure 1. Brown (2017) and CHRT demand this of us and we propose that a larger discussion based upon the ideas in Figure 1 can begin to result in change. It will also require courage by the various professions working in and connecting with child protection to demand a change in the core default frames of what family is about, what is successful parenting and how would best interest be observed from Indigenous worldviews. The ethical space is one where reconciliation can take place because Canada comes to recognize that what we have been doing is wrong, ineffective and harmful. We either enter into reconciliation or we sustain colonization.

Figure 1.

Blackfoot Trilogy of Teachings—this trilogy shows the complex manner in the reconsideration of child protection assessment and judicial decision making that will be explored. It requires that we self-examine and do so in relationship with others. This will result in the constant circle of moving from misunderstanding to feeling that something is understood to truly understanding. The more one understands, the more one comes back to misunderstanding and so it is a loop. It is therefore a process of looking and listening to learn. The process also demands that we are conscious of our statements (such as presenting evidence to the court and in judicial decision making). At the center is the recognition of the multiple intersections in this work and the reality that impacts are constant.

Other countries with histories of colonization share many similar outcomes (Sinha et al. 2021). As Sinha et al. (2021) notes, “Settler colonial histories in Canada, the United States, Australia and New Zealand have systematically disrupted traditional ways of life, community, spiritual practices and family structures for Indigenous Peoples. This pattern has been described as cultural genocide” (p. 2). Changes to these colonial approaches require intentional activity that includes legislation and its application through the courts to build a different system that honours Indigenous peoples, cultures, traditions and capacities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.C., D.L., B.C. and R.B.C.; writing—orignal draft, P.C.; writing—review and editing, P.C., D.L. and B.C.; Indigenous knowledge supervision, R.B.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict.

References

Legal Sources

CasesBritish Columbia (Child, Family and Community Service) v. S.H., 2020 BCPC 82.Brown v Canada (Attorney General) 2017 ONSC 2.Canada (Attorney General) v. Pictou Landing First Nation, 2013 FC 342.Descheneaux c. Canada (Procureur Général), 2015 QCCS 3555.Ewert v. Canada, 2018 SCC 30, [2018] 2 S.C.R. 165.First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v. Attorney General of Canada (for the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada), 2020a CHRT 20.First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v. Attorney General of Canada (for the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada), 2020b CHRT 7.First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v. Attorney General of Canada (for the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada), 2019a CHRT 39.First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v. Attorney General of Canada (for the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada), 2019b CHRT 7.First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v. Attorney General of Canada (for the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada), 2017a CHRT 14.First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v. Attorney General of Canada (for the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada), 2017b CHRT 35.First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v. Attorney General of Canada (for the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada), 2016a CHRT 16.First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v. Attorney General of Canada (for the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada), 2016b CHRT 11.First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v. Attorney General of Canada (for the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada), 2016c CHRT 10.First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v. Attorney General of Canada (for the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada), 2016d CHRT 2.First Nations Child & Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v. Attorney General of Canada (for the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada), 2015a CHRT 14.First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v. Attorney General of Canada (for the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada), 2015b CHRT 1.First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v. Attorney General of Canada (for the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Canada), 2014a CHRT 12.First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v. Attorney General of Canada (for the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Canada), 2014b CHRT 2.First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v. Attorney General of Canada (for the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Canada), 2013a CHRT 16.First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v. Attorney General of Canada (for the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada)., 2013b CHRT 11.First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v. Attorney General of Canada (for the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada)., 2012a CHRT 28.First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v. Attorney General of Canada (for the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada)., 2012b CHRT 23.First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v. Attorney General of Canada (for the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada), 2012c CHRT 18.First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v. Attorney General of Canada (for the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada), 2012d CHRT 17.First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v. Attorney General of Canada (for the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada), 2012e CHRT 16.M.M. v T.B. 2017 BCCA 296 at para 97.R. v. Gladue, 1999. 1 S.C.R. 688.R. v. Mohan, 1994. 2 S.C.R. 9.Racine v Woods, 1983. 2 SCR 173.SM v Alberta (Child, Youth and Family Enhancement Act, Director), 2019 ABQB 972.URM (Re) 2018 ABPC 116.Van de Perre v Edwards, 2001 SCC 60 at para 39, [2001] 2 SCR 1014.White Burgess, [2015] SCC 23.- LegislationAn Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families (S.C. 2019, c. 24).Indian Act (R.S.C. 1985 c1-5) as at 4 May 2021. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/PDF/I-5.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2020).

Published Sources

- Barnes, Rosemary, and Nina Josefowitz. 2019. Indian residential schools in Canada: Persistent impacts on Aboriginal students’ psychological development and functioning. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne 60: 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezanson, Karen. 2018. Caring Society v Canada: Neoliberalism, Social Reproduction, and Indigenous Child Welfare (Part I). Journal of Law and Social Policy 28: 152–73. [Google Scholar]

- Blackstock, Cindy. 2007. Residential Schools: Did They Really Close or Just Morph Into Child Welfare? Indigenous Law Journal 6: 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Blackstock, Cindy. 2016. The Complainant: The Canadian Human Rights Case on First Nations Child Welfare. McGill Law Journal/Revue de droit de McGill 62: 285–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blackstock, Cindy, Tara Prakash, John Loxley, and Fred Wien. 2005. Wen:De: We Are Coming to the Light of Day. Ottawa: First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Bonds, Anne, and Joshua Inwood. 2016. Beyond white privilege: Geographies of white supremacy and settler colonialism. Progress in Human Geography 40: 715–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourassa, Carrie, Betty McKenna, and Darlene Juschka. 2017. Listening to the Beat of Our Drum: Indigenous Parenting in Contemporary Society. Bradford: Demeter Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, Susan B., and Krishna Dhaliwal. 2015. “Race is not a determinative factor”: Mixed race children in custody cases in Canada. Canadian Family Law Journal 29: 309–80. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, Lori Udoka Okpalauwaekwe, Cheryl L. Waldner, and Lalita A. Bharadwaj. 2016. Drinking water quality in Indigenous communities in Canada and health outcomes: A scoping review. International Journal of Circumpolar Health 75: 32366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brown-Rice, Kathleen. 2013. Examining the theory of historical trauma among Native Americans. The Professional Counselor 3: 117–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choate, Peter. 2019. The call to decolonize: Social work’s challenge for working with Indigenous peoples. British Journal of Social Work 49: 1081–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choate, Peter, and Gabrielle Lindstrom. 2018. Parenting Capacity Assessment as a Colonial strategy. Canadian Family Law Quarterly 37: 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Choate, Peter, and Amber McKenzie. 2015. Psychometrics in parenting capacity assessments: A problem for Indigenous parents. First Peoples Child and Family Review 10: 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Choate, Peter, Taylor Kohler, Felicia Cloete, Brandy CrazyBull, Desi Lindstrom, and Parker Tatoulis. 2019. Rethinking Racine v Woods from a Decolonizing Perspective: Challenging the Applicability of Attachment Theory to Indigenous Families Involved with Child Protection. Canadian Journal of Law and Society/La Revue Canadienne Droit et Société 34: 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choate, Peter, Brandy CrazyBull, Desi Lindstrom, and Gabrielle Lindstrom. 2020a. Where do we go from here? Ongoing colonialism from Attachment Theory. Aoteroa New Zealand Social Work 32: 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choate, Peter, Natalie St-Denis, and Bruce MacLaurin. 2020b. At the beginning of the curve: Social work education and Indigenous content. Journal of Social Work Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, Aimee. 2013. Reading beyond the Lines: Oral Understandings and Aboriginal Litigation. Paper presented at Canadian Institute for the Administration of Justice Conference: How Do We Know What We Think We Know: Facts in the Legal System, Winnipeg, MB, Canada, October 11; Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=4&ved=2ahUKEwij7-HP3qXiAhULuZ4KHehiDcYQFjADegQIBRAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fciaj-icaj.ca%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2Fdocuments%2Fimport%2F2013%2F843.pdf%3Fid%3D703%261552129688&usg=AOvVaw2Vwn-zjiQJNzMmUtYL2FpO (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1991. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review 43: 1241–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, Amber, Jeffrey Schiffer, Barbara Fallon, Emmaline Houston, Tara Black, Rachael Lefebvre, Joanne Filippelli, Nicollette Joh-Carnella, and Nico Trocmé. 2021. Mashkiwenmi-Daa Noojimowin: Let’s Have Strong Minds for the Healing. (First Nations Ontario Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect 2018). Toronto: Child Welfare Research Portal. [Google Scholar]

- Child and Youth Advocate of Alberta (CYAA). 2016. Investigative Review: 4-Year-Old Marie. Edmonton: CYAA. [Google Scholar]

- Child and Youth Advocate of Alberta (CYAA). 2017a. Investigative Review: 16-Year-Old Dillon: Serious Injury. Edmonton: CYAA. [Google Scholar]

- Child and Youth Advocate of Alberta (CYAA). 2017b. Investigative Review: 15-Year-Old Jimmy. Edmonton: CYAA. [Google Scholar]

- Child and Youth Advocate of Alberta (CYAA). 2018. Investigative Review: 19-Year-Old Dakota. Edmonton: CYAA. [Google Scholar]

- Ermine, W. 2015. The ethical space of engagement. Indigenous Law Journal 6: 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- First Nations Education Council (FNEC). 2009. Paper on First Nations Education Funding. Wenake: FNEC. [Google Scholar]

- Friedland, Hadley, and Koren Lightning-Earl. 2020. Bill C-92—From Compliance to Connection. Presentation to the Canadian Association of Social Workers, Continuing Education Program. Ottawa: CASW, Available online: https://www.casw-acts.ca/en/webinar/bill-c-92-act-respecting-first-nations-inuit-and-m%C3%A9tis-children-youth-and-families (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Goldstein, Joseph, Albert Solnit, and Anna Freud. 1973. Beyond the Best Interests of the Child. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, Jospeh, Albert Solnit, Sonja Goldstein, and Anna Freud. 1996. The Best Interests of the Child: The Least Detrimental Alternative. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Gosine, Kevin, and Gordon Pon. 2011. On the front lines: The voices and experiences of radicalized child welfare workers in Toronto, Ontario. Journal of Progressive Human Services 22: 135–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, Sandy. 2013. Whitestream Feminism and the Colonialist Project: A review of contemporary feminism pedagogy and praxis. Educational Theory 53: 329–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnett, Paul H., and Gerald Featherstone. 2020. The role of decision making in the over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in the Australian child protection system. Children and Youth Services Review, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Samuel H. S. 1991. Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Response of the Newfoundland Criminal Justice System to Complaints. St. John’s: Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, Theodore. 2013. The Legacy of Phoenix Sinclair: Achieving the Best for All Our Children. Winnipeg: Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, Patrick. 1983. Native Children and the Child Welfare System. Toronto: Canadian Council on Social Development. [Google Scholar]

- Kimelman, Edward. 1985. No Quiet Place. Review Committee on Métis and Indian Placements and Adoptions. Winnipeg: Committee. [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom, Gabrielle, and Peter W. Choate. 2017. Nistawatsiman: Rethinking Assessment of Indigenous Parents for Child Welfare Following the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. First Peoples Child & Family Review 11: 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Loxley, John, Linda De Riviere, Tara Prakash, Cindy Blackstock, Fred Wien, and Shelley Thomas Prokop. 2005. Wen:De: The Journey Continues. The National Policy Review on First Nations Child and Family Services Research Project: Phase 3. Ottawa: First Nations Child and Family Caring Society. [Google Scholar]

- Manitoba Advocate for Children and Youth (MACY). 2016. On the Edge between Two Worlds: Community Narratives on the Vulnerability of Marginalized Indigenous Girls. Winnipeg: MACY. [Google Scholar]

- Manitoba Advocate for Children and Youth (MACY). 2018. In Need of Protection: Angel’s Story. Winnipeg: MACY. [Google Scholar]

- Mako, Shamiran. 2012. Cultural Genocide and Key International Instruments: Framing the Indigenous Experience. International Journal on Minority and Group Rights 19: 175–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makokis, Loena, Ralph Bodor, Avery Calhoun, and Stephanie Tyler. 2020. Ohpikinâwasowin: Growing a Child: Implementing Indiegnous Ways of Knowing with Indigenous Families. Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart, Josephine Chase, Jennifer Elkins, and Deborah Alschul. 2011. Historical trauma among Indigenous peoples of the Americas: Concepts, research and clinical considerations. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 43: 282–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, Celeste. 2018. A Report on Children and Families Together: An Emergency Meeting on Indigenous Child and Family Services. Ottawa: Indigenous Services Canada. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, Holly, Colleen Varcoe, Annette J. Browne, and Linda Day. 2016. Disrupting the Continuities among Residential Schools, the Sixties Scoop, and Child Welfare: An Analysis of Colonial and Neocolonial Discourses. The International Indigenous Policy Journal, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metallic, Naimoi W. 2018. A Human Right to Self-Government over First Nations Child and Family Services and Beyond: Implications of the Caring Society Case. Journal of Law and Social Policy 28: 4–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mosher, Janet, and Jeffery Hewitt. 2018. Reimagining Child Welfare Systems in Canada. Journal of Law and Social Policy 28: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mosoff, Judith, Isabelle Grant, Susan Boyd, and Ruben Lindy. 2017. Intersection challenges: Mothers and child protection law in B.C. UBC Law Review 50: 435–504. [Google Scholar]

- National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health (NCCIH). 2017. Indigenous Children and the Child Welfare System in Canada. Prince George: National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health. [Google Scholar]

- Niessen, Shauna. 2017. Shattering the Silence: The Hidden History of Indian Residential Schools in Saskatchewan. Regina: Faculty of Education, University of Regina. [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC). 2018. Interrupted Childhoods: Over-Representation of Indigenous and Black Children in Ontario Child Welfare. Toronto: OHRC. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP). 1996. Bridging the Cultural Divide: A Report on Aboriginal People and Criminal Justice in Canada. Ottawa: RCAP. [Google Scholar]

- Representative for Children and Youth (RCY). 2014. Lost in the Shadows: How a Lack of Help Meant a Loss of Hope for One First Nations Girl. Victoria: RCY. [Google Scholar]

- Representative for Children and Youth (RCY). 2015. Paige’s Story: Abuse, Indifference and a Young Life Discarded. Victoria: RCY. [Google Scholar]

- Representative for Children and Youth (RCY). 2016. A Tragedy in Waiting: How B.C.’s Mental Health System Failed One First Nations Youth. Victoria: RCY. [Google Scholar]

- Representative for Children and Youth (RCY). 2017. Broken Promises: Alex’s Story. Victoria: RCY. [Google Scholar]

- Representative for Children and Youth (RCY). 2018. Alone and Afraid: Lessons Learned from the Ordeal of a Child with Special Needs and His Family. Victoria: RCY. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, Kenn. 2007. On the matter of cross-cultural Aboriginal adoptions. In Putting a Human Face on Child Welfare: Voices from the Prairies. Edited by Ivan Brown, Ferzana Chaze, Don Fuchs, Jean Lafrance, Sharon McKay and Shelley T. Prokop. Regina: University of Regina Press, pp. 189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Saskatchewan Advocate (SA). 2016a. Duty to Protect. Regina: SA. [Google Scholar]

- Saskatchewan Advocate (SA). 2016b. The Silent World of Jordan. Regina: SA. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, Raven. 2007a. Identity lost and found: Lessons from the sixties scoop. First Peoples Child & Family Review 3: 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, Raven. 2007b. All My Relations—Native Transracial Adoption: A Critical Case Study of Cultural Identity. Ph.D. thesis, Faculty of Social Work, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, R. 2016. The Indigenous child removal system in Canada: An examination of legal decision-making and racial bias. First Peoples Child & Family Review 11: 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, Vandna, Nico Trocmé, Barbara Fallon, Bruce MacLaurin, Elizabeth Fast, Shelley Thomas Prokop, Tara Petti, Anna Kozlowski, Tara Black, Pamela Weightman, and et al. 2011. Kiskisik Awasisak: Remember the Children. Understanding the Overrepresentation of First Nations Children in the Child Welfare System. Ontario: Assembly of First Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, Vandna, Johanna Caldwell, Leah Pauls, and Paulo R. Fumaneri. 2021. A review of literature on the involvement of children from Indigenous communities in Anglo child welfare systems: 1973–2018. The International Indigenous Policy Journal, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sixties. 2018. Sixties scoop survivors: Leticia’s story. In Community Connection. Regina: North Central Community Association, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. 2016. Living Arrangements of Aborigibal Chidlren Aged 14 Years and Under. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Titley, Brian. 1986. A Narrow Vision: Duncan Campbell Scott and the Administration of Indian Affairs in Canada. Vancouver: UBC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Truth and Reconciliation Canada (TRC). 2015a. Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summaryof the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC). 2015. Canada’s Residential Schools: The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (v. 5). Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Trocmé, Nico, Della Knoke, and Cindy Blackstock. 2004. Pathways to the overrepresentation of Indigenous children in Canada’s child welfare system. Social Service Review 78: 577–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turpel-Lafond, M. E. 2020. Primer on Practice Shifts Required with Canada’s Act Respecting First Nations, Inuit and Metis Children, Youth and Families Act. Assembly of First Nations. Available online: http://irshdc.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2019/12/Policy_Primer_Report_ENG.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2020).

- Union of Ontario Indians. 2013. An Overview of the Indian Residential School System. Written by the Union of Ontario Indians Based on Research Compiled by Karen Restoule. Available online: http://www.anishinabek.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/An-Overview-of-the-IRS-System-Booklet.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Wattman, Jocelyn. 2016. The Legacy of Duncan Campbell Scott: More than just a Canadian Poet. Ottawa: First Nations Child and Family Caring Society. [Google Scholar]

- Whitcomb, ed. 2019. Understanding First Nations: The Legacy of Canadian Colonialism. Ottawa: From Sea to Sea Enterprises. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | It should be noted that, at the time of this writing, a series of unidentified graves have been found at the sites of some former Indian Residential Schools. Further searches are underway at a number of other former IRS sites. This adds to the understanding of intergenerational trauma for Indigenous peoples for whom many children were taken to IRS and their fates were never known. This was also true during the Sixties Scoop when children were taken away for adoption, resulting in the loss all contact between their biological families and cultures. |

| 2 | Jordan’s Principle is a legal rule named in memory of Jordan River Anderson, a First Nations child from Norway House Cree Nation in Manitoba. Born with complex medical needs, Jordan spent more than two unnecessary years in hospital waiting to leave, while the Province of Manitoba and the federal government argued over who should pay for his at home care—care that would have been paid for immediately had Jordan not been First Nations. Jordan died in the hospital at the age of five years old, having never spent a day in a family home. Source: First Peoples Child and Family Caring Society. |

| 3 | These changes arose as a results of the decision Descheneaux c. Canada (Procureur Général, 2015 QCCS 3555—accessed on 10 September 2020. These include the cousins issue—differential treatment of first cousins whose grandmother lost status due to marriage with a non-Indian before 17 April 1985; the siblings issue—differential treatment of women who were born out of wedlock to Indian fathers between 4 September 1951 and 17 April 1985; the issue of omitted minor children—differential treatment of minor children who were born of Indian parents or of an Indian mother, but could lose entitlement to Indian status between 4 September 1951 and 17 April 1985 if they were still unmarried minors at the time of their mother’s marriage; and the unstated or unknown parent issue—in response to the Ontario Court of Appeal’s Gehl decision, which deals with unstated/unknown parent issue, Bill S-3 provides flexibility for the Indian Registrar to consider various forms of evidence in determining eligibility for registration in situations of an unstated or unknown parent, grand-parent or other ancestor (https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1467214955663/1572460311596#chp5 (accessed on 5 December 2020)). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).