Modeling Radiation-Induced Degradation in Top-Gated Epitaxial Graphene Field-Effect-Transistors (FETs)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

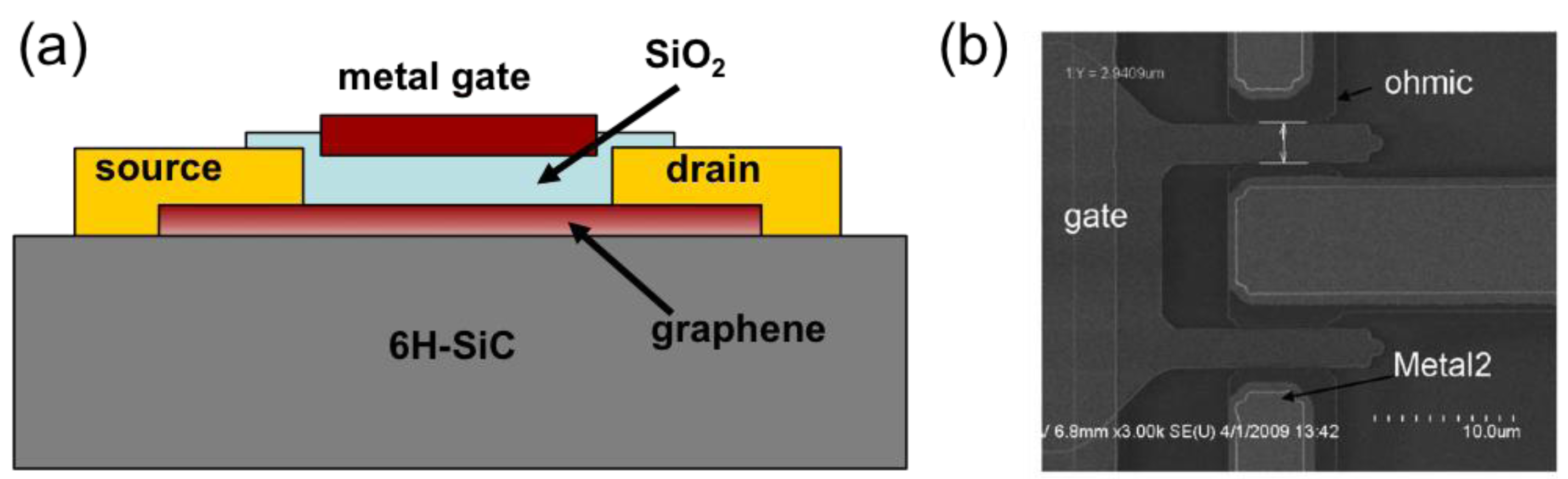

2. Experimental Section

3. Results and Discussion

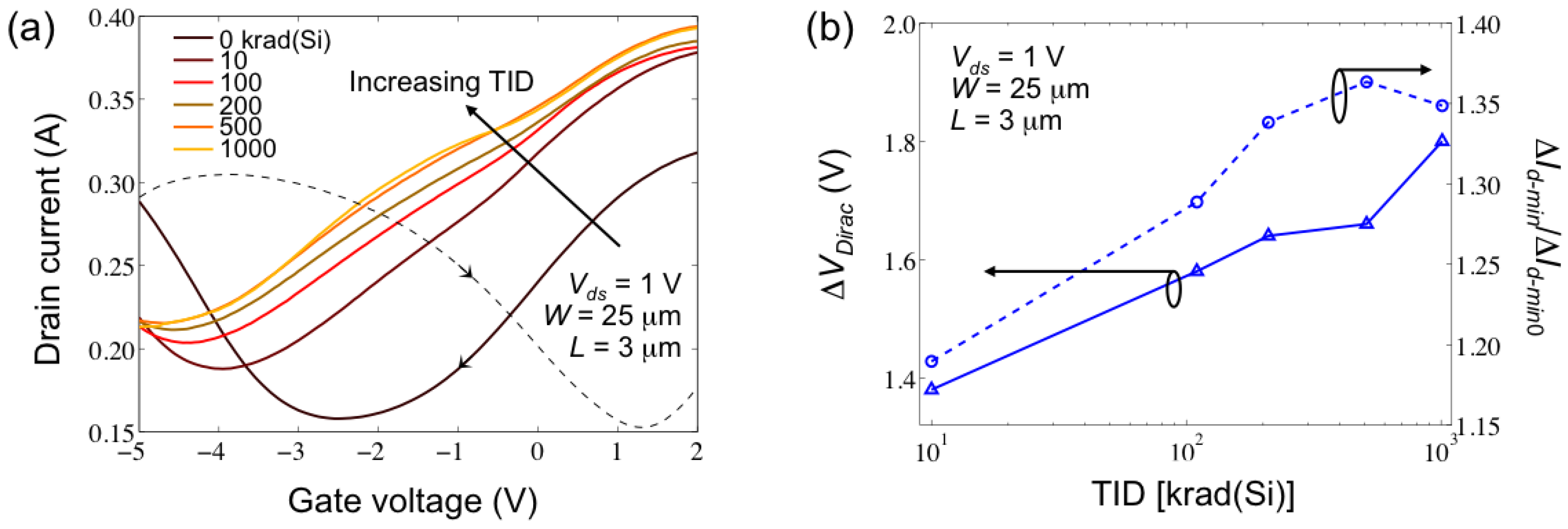

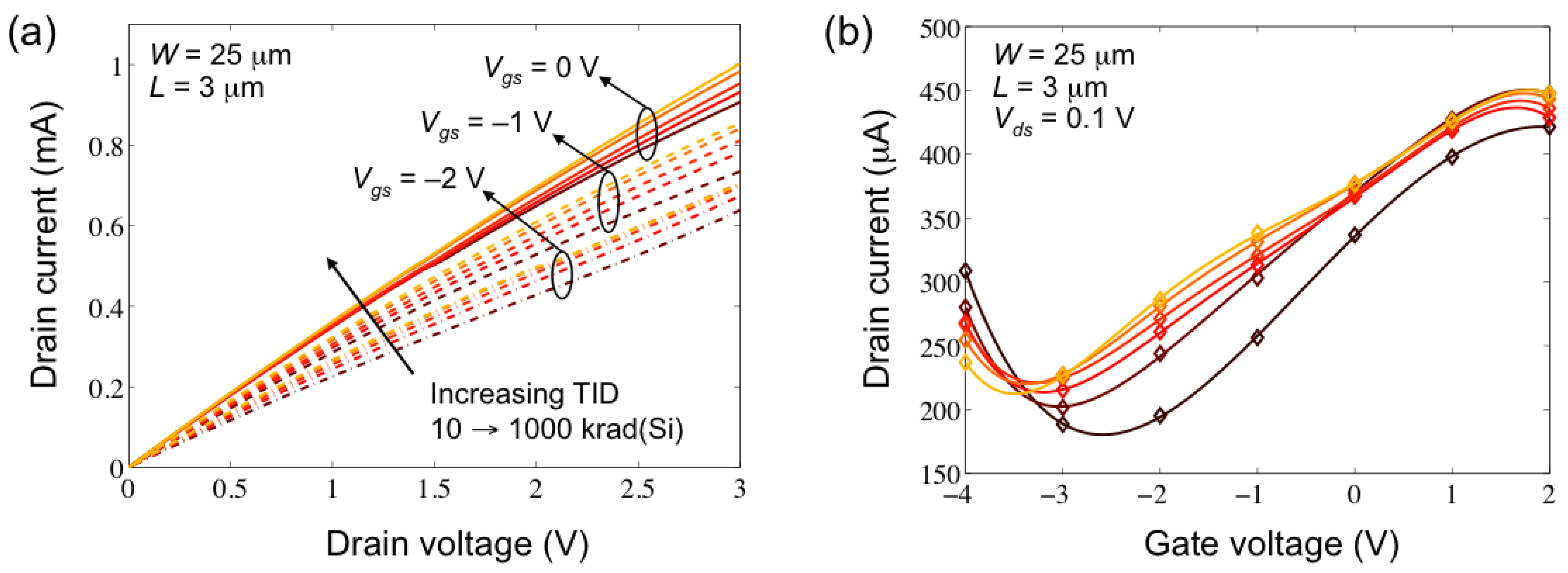

3.1. Current-Voltage Characteristics

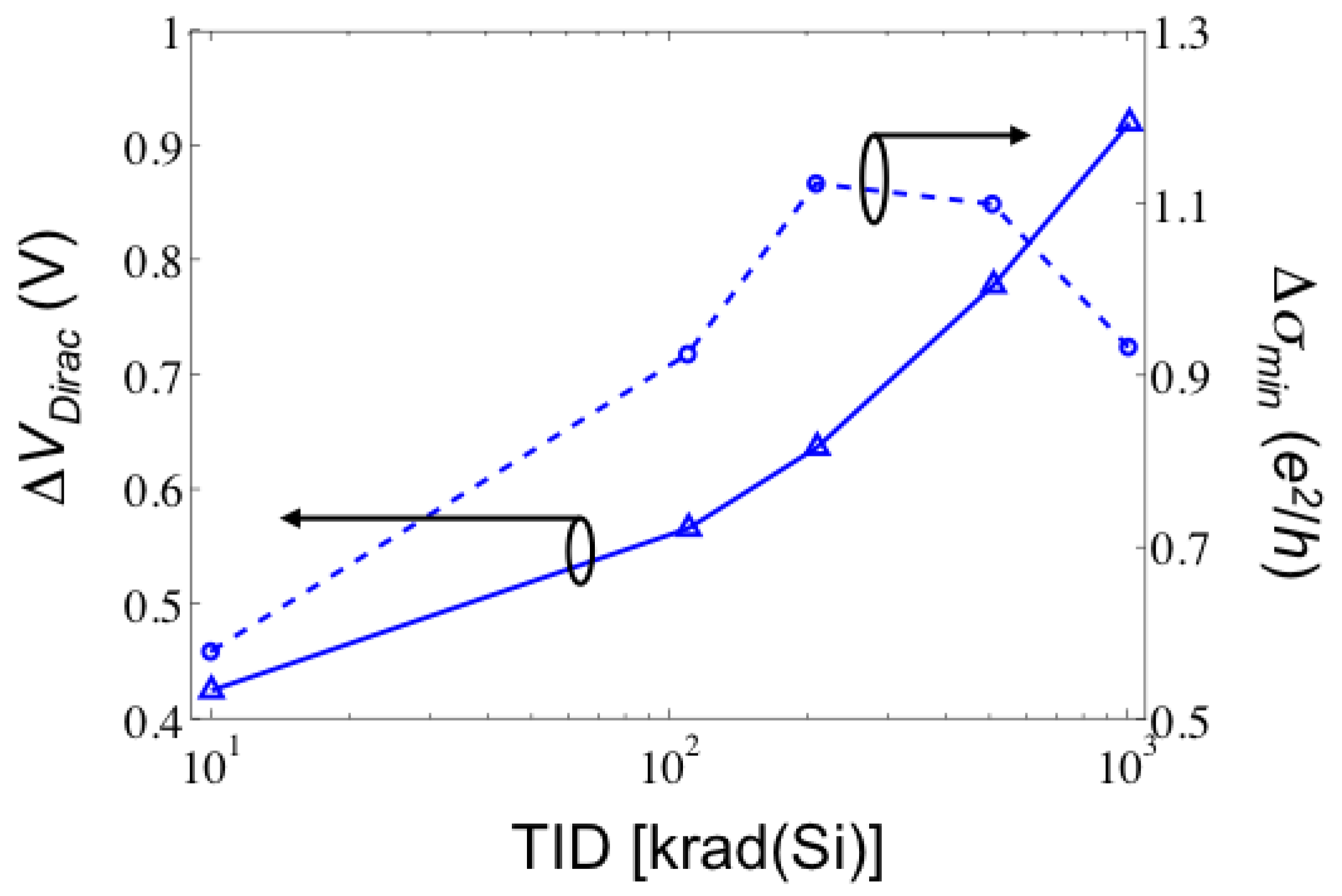

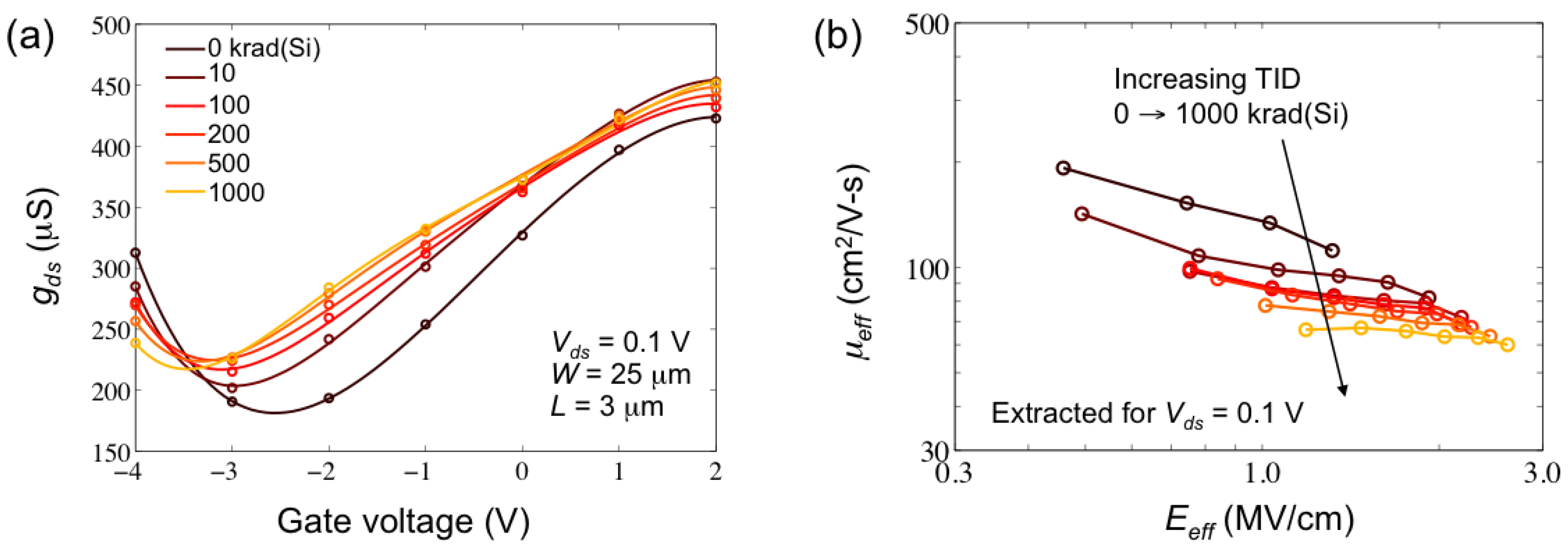

, ΔVDirac and Δσmin. Using ΔVDirac and Δσmin plotted in Figure 4 (extracted from the Id-Vg representations in Figure 3b) ensures that any contributions from hysteresis effects are equivalent for the extractions of gds since the same Id-Vds measurements are used for all of the extractions.

, ΔVDirac and Δσmin. Using ΔVDirac and Δσmin plotted in Figure 4 (extracted from the Id-Vg representations in Figure 3b) ensures that any contributions from hysteresis effects are equivalent for the extractions of gds since the same Id-Vds measurements are used for all of the extractions.

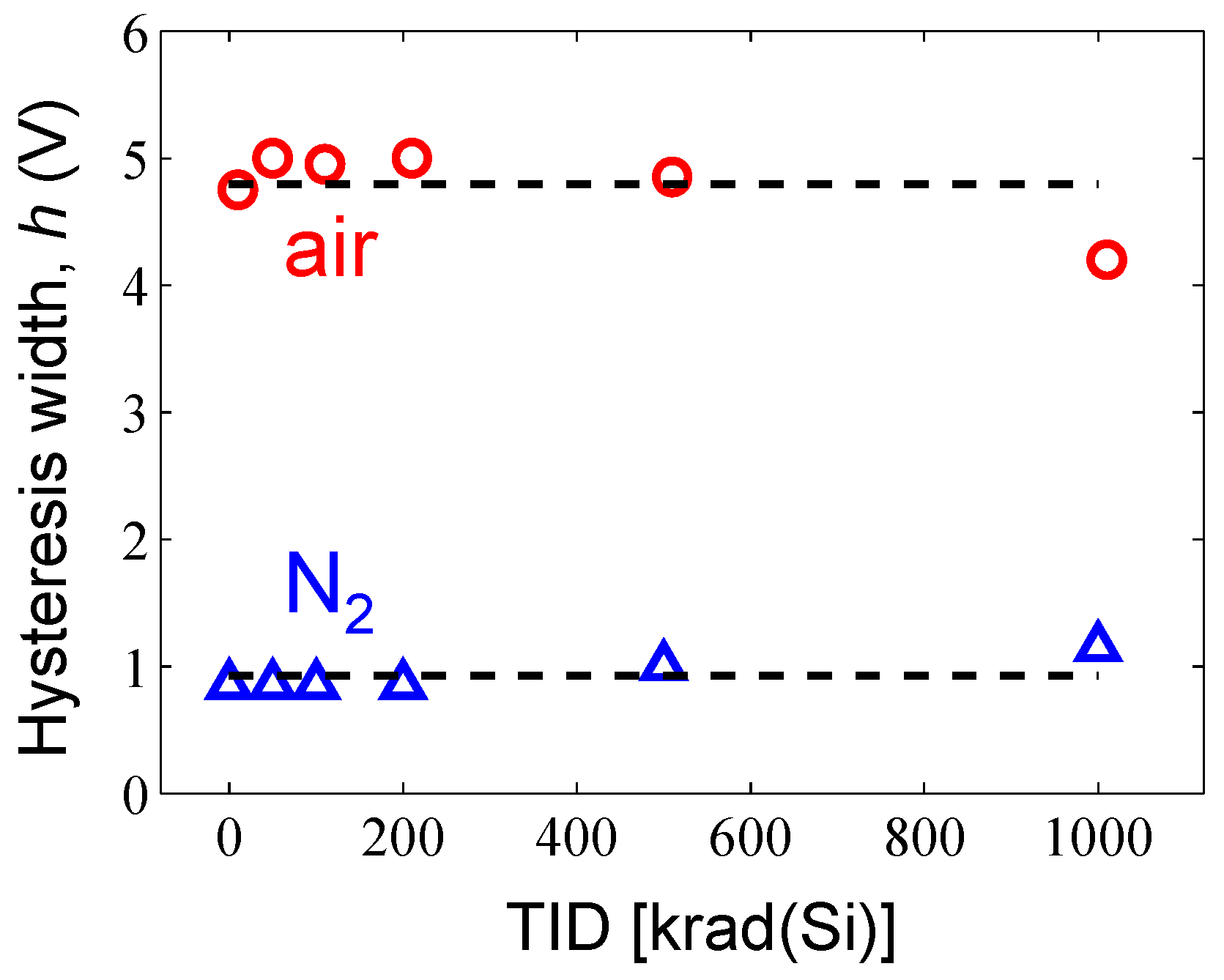

3.2. Experimental Ambient Conditions

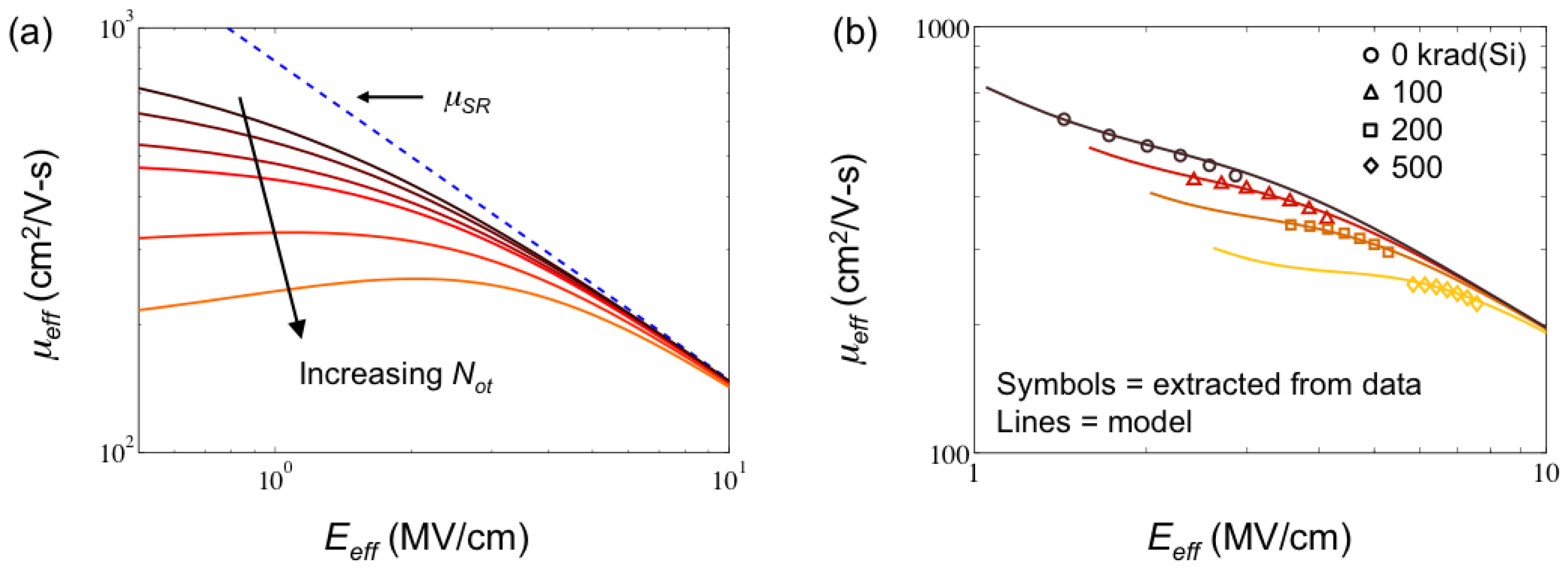

3.3. Mobility Degradation

4. Modeling

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Geim, K.; Novoselov, K.S. The rise of graphene. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwierz, F. Graphene transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010, 5, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meric, I.; Han, M.Y.; Young, A.F.; Ozyilmaz, B.; Kim, P.; Shepard, K.L. Current saturation in zero-bandgap, top-gated graphene field-effect transitors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2008, 3, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.X.; Newaz, A.K.; Wang, B.; Bhandaru, S.; Zhang, C.X.; Fleetwood, D.M.; Bolotin, K.I.; Pantelides, S.T.; Alles, M.L.; Schrimpf, R.D.; et al. Low-energy X-ray and ozone-exposure induced defect formation in graphene materials and devices. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2011, 58, 2961–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cress, C.D.; McMorrow, J.J.; Robinson, J.T.; Landi, B.J.; Hubbard, S.M.; Messenger, S.R. Radiation effects in carbon nanoelectronics. Electronics 2012, 1, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai-Xing, H.; Zhuo-Yu, J.; Li-Wei, S.; Ying-Ping, C.; Hong, W.; Xin, L.; Dong-Mei, L.; Ming, L. Gamma radiation caused graphene defects and increased carrier density. Chin. Phys. B 2011, 20, 086102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.X.; Zhang, E.X.; Fleetwood, D.M.; Alles, M.L.; Schrimpf, R.D.; Song, E.B.; Sung, M.K.; Galatsis, K.; Wang, K.L.W. Electrical stress and total ionizing dose effects on graphene-based non-volatile memory devices. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2012, 59, 2974–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cress, C.; McMorrow, J.; Robinson, J.; Friedman, A.; Landi, B. Radiation effects in single-walled carbon nanotube thin-film-transistors. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2010, 57, 3040–3045. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Zhou, C.; Wormuth, R.; Tyree, V.; Fritze, M.; McMarr, P.; Hughes, H. Total Dose Radiation Effects in Carbon Nanotube Transistors. In Presented at the Government Microcircuit Applications and Critical Technology Conference, Las Vegas, NV, USA, March 2012.

- Moon, J.S.; Curtis, D.; Bui, S.; Hu, M.; Gaskill, D.K.; Tedesco, J.L.; Asbeck, P.; Jernigan, G.G.; VanMil, B.L.; Myers-Ward, R.L.; et al. Top-gated epitaxial graphene FETs on Si-Face SiC Wafers With a peak transconductance of 600 mS/mm. IEEE Electron Dev. Lett. 2010, 31, 260–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, S.; Craciun, M.F.; Yamamoto, M.; Tarucha, S.; Morpurgo, A.F. Double-gated graphene-based devices. New J. Phys. 2009, 11, 095018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-H.; Jang, C.; Adam, S.; Fuhrer, M.S.; Williams, E.D.; Ishigami, M. Charge impurity scattering in graphene. Nat. Phys. 2008, 4, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Javey, A.; Vermesh, O.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Dai, H. Hysteresis caused by water molecules in carbon nanotube field-effect transistors. Nano Lett. 2003, 3, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.C.; Plummer, J.D. Electron mobility in inversion and accumulation layers on thermally oxidized silicon surfaces. IEEE J. Solid-State Circ. 1980, 27, 1497–1508. [Google Scholar]

- Wehling, T.O.; Şaşıoğlu, E.; Friedrich, C.; Lichtenstein, A.I.; Katsnelson, M.I.; Blügel, S. Strength of effective coulomb interactions in graphene and graphite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 236805. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.; Akerman, N.; Ulbricht, G.; Lohmann, T.; Smet, J.H.; von Klitzing, K.; Yacoby, A. Observation of electron-hole puddles in graphene using a scanning single-electron transistor. Nat. Phys. 2008, 4, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-H.; Cullen, W.G.; Jang, C.; Fuhrer, M.S.; Williams, E.D. Defect scattering in graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 236805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, S.; Hwang, E.H.; Galitski, V.M.; Sarma, S.D. A self-consistent theory for graphene transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 18392–18397. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, D.B.; Perebeinos, V.; Ling, Y.; Dimitrakopoulos, C.; Avouris, P. Charge trapping and scattering in epitaxial graphene. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 205417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Woo, J. Measurement and modeling of the n-channel and p-channel MOSFET’s inversion layer mobility at room and low temperature operation. J. Phys. IV France 1996, 6, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Thiele, S.A.; Schaefer, J.A.; Schwierz, F. Modeling of graphene metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistors with gapless large-area graphene channels. J. Appl. Phys. 2010, 107, 094505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meric, I.; Baklitskaya, N.; Kim, P.; Shepard, K.L. RF Performance of Top-Gated, Zero-Bandgap Graphene Field-Effect Transistors. In Proceedings of Electron Devices Meeting, San Francisco, CA, USA, December 2008; pp. 1–4.

- Champlain, J.G. A first principles theoretical examination of graphene-based field effect transistors. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 109, 084515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cress, C.D.; Champlain, J.G.; Esqueda, I.S.; Robinson, J.T.; Friedman, A.L.; McMorrow, J. Total ionizing dose induced charge carrier scattering in graphene devices. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2012, 59, 3045–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Esqueda, I.S.; Cress, C.D.; Anderson, T.J.; Ahlbin, J.R.; Bajura, M.; Fritze, M.; Moon, J.-S. Modeling Radiation-Induced Degradation in Top-Gated Epitaxial Graphene Field-Effect-Transistors (FETs). Electronics 2013, 2, 234-245. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics2030234

Esqueda IS, Cress CD, Anderson TJ, Ahlbin JR, Bajura M, Fritze M, Moon J-S. Modeling Radiation-Induced Degradation in Top-Gated Epitaxial Graphene Field-Effect-Transistors (FETs). Electronics. 2013; 2(3):234-245. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics2030234

Chicago/Turabian StyleEsqueda, Ivan S., Cory D. Cress, Travis J. Anderson, Jonathan R. Ahlbin, Michael Bajura, Michael Fritze, and Jeong-S. Moon. 2013. "Modeling Radiation-Induced Degradation in Top-Gated Epitaxial Graphene Field-Effect-Transistors (FETs)" Electronics 2, no. 3: 234-245. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics2030234