Abstract

The design, development and clinical success of HIV protease inhibitors represent one of the most remarkable achievements of molecular medicine. This review describes all nine currently available FDA-approved protease inhibitors, discusses their pharmacokinetic properties, off-target activities, side-effects, and resistance profiles. The compounds in the various stages of clinical development are also introduced, as well as alternative approaches, aiming at other functional domains of HIV PR. The potential of these novel compounds to open new way to the rational drug design of human viruses is critically assessed.

Abbreviations

APV ----- Amprenavir

ATV ----- Atazanavir

BCV ----- Brecanavir

BID ----- twice per day

CYP450 ----- Cytochrome P450/3A4

DRV ----- Darunavir

FDA ----- Food and Drug Administration

FPV, fAPV ----- Fosamprenavir

HAART ----- Highly active antiretroviral therapy

IDV ----- ndinavir

Kd ----- Dissociation constant

Ki ----- Inhibition constant

LPV ----- Lopinavir

NFV ----- Nelfinavir

PIs ----- Protease inhibitors

PR ----- Protease

q24h ----- every 24 hours

RTV ----- Ritonavir

SQV ----- Saquinavir

TPV ----- Tipranavir

1.Introduction

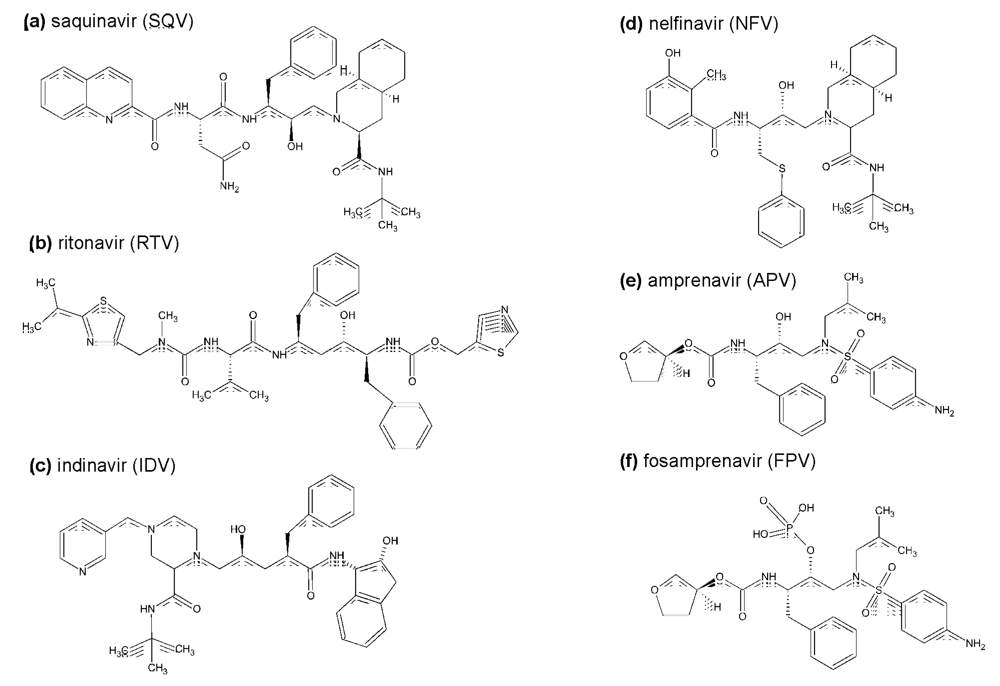

The aspartic protease of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV PR) is responsible for the cleavage of the viral Gag and Gag-Pol polyprotein precursors into mature, functional viral enzymes and structural proteins. This process, called viral maturation, which leads to the final morphological rearrangements, is indispensable for production of infectious viral particles []. If HIV-PR is inhibited, the nascent virions cannot go on to attack other cells and the spreading of HIV is therefore stopped. The introduction of HIV protease inhibitors (PIs) in 1995 and the application of highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART), i.e., combination of PI with other antiretrovirals, mainly inhibitors of the HIV reverse transcriptase, resulted in a vastly decreased mortality (Figure 1) and a prolonged life expectancy of HIV-positive patients. The success story of the therapeutic use of HIV protease inhibitors is not only a remarkable achievement of modern molecular medicine, but it also represents a unique showcase for the power and limitations of a structure-based drug design in general.

Although the success of HIV PIs has been remarkable and there are not fewer than nine of these compounds currently approved by the FDA as antiviral agents, for several reasons both the academia as well as the industry need to continue in their effort to develop novel, more potent compounds.

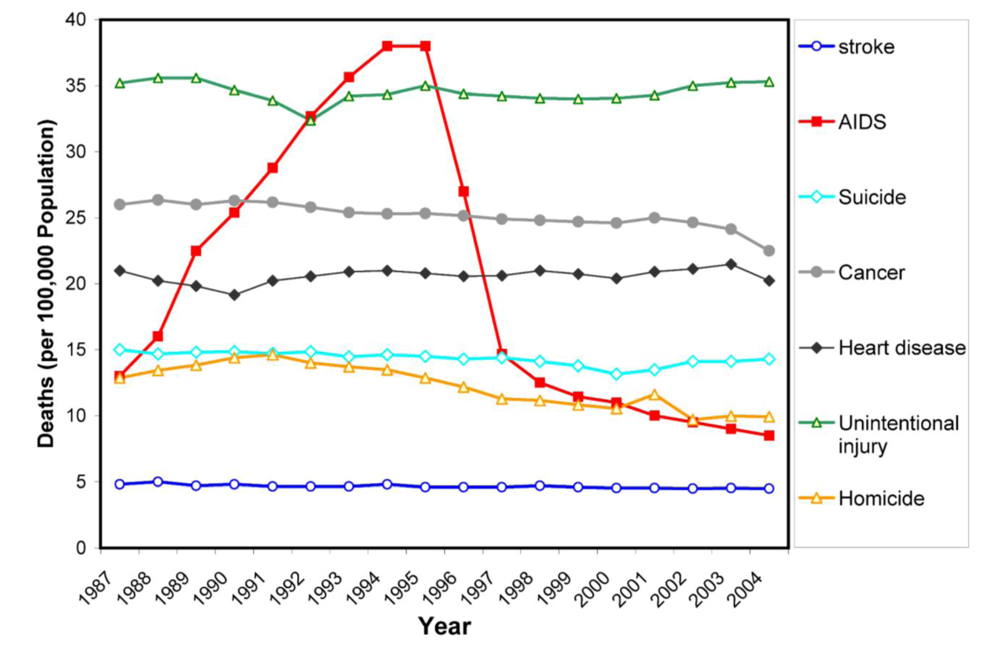

First, there is a problem of antiviral drug resistance. The high mutation rate caused by the lack of proofreading activity of the viral reverse transcriptase, the dynamic viral replication in HIV-positive individuals, together with potential dual infection and insufficient effect of drugs lead to rapid selection of viral species resistant to the currently used inhibitors. The pattern of mutations associated with the viral resistance is extremely complex (Figure 2, Table 1). The mutations are selected not only in the protease substrate binding cleft in the direct proximity of an inhibitor, but also outside the active site of the enzyme. Besides the common mechanism of amino acid substitution, insertions in the PR have also been observed to be selected during antiretroviral therapy [,]. Furthermore, HIV occasionally rescues its fitness under the selection pressure of PIs by changing the protease substrate, i.e., the polyprotein cleavage sites [,]. Some of these gag mutations have been shown to confer the viral resistance even without the corresponding changes in the PR []. The mechanism of resistance development and the structural aspects of the interaction of PIs with the active cleft of mutated HIV PR species are discussed in other reviews in this volume.

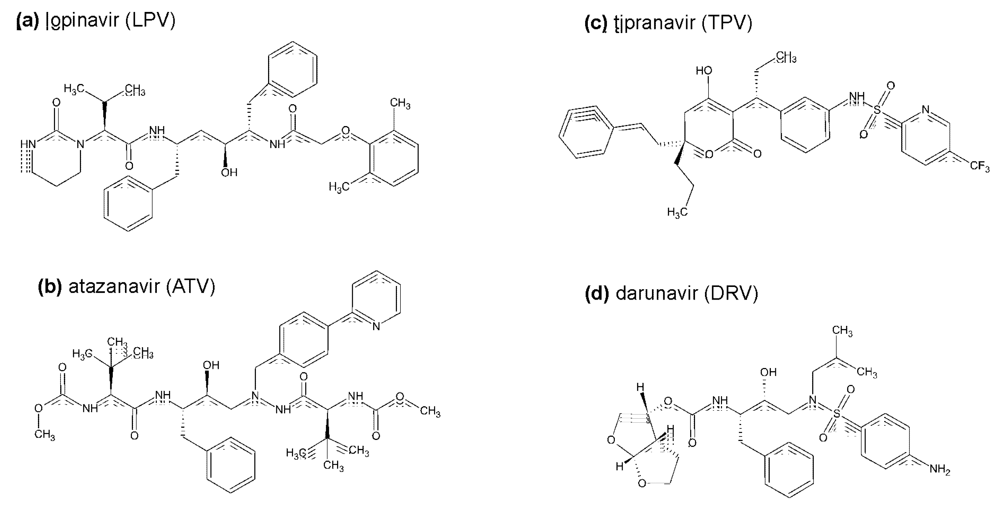

Figure 1.

Trends in annual rates of death due to 7 leading causes among persons 25-44 years old in the United States during period 1987-2004. Dramatic decrease in the rate of death due to AIDS coincides with the introduction of HIV protease inhibitors (source: National Vital Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta).

Secondly, the clinical use of PIs is further affected by their high price and by problems of tolerability, toxicity, and adherence. Before the introduction of the first PIs into the clinical practice, optimistic expectations prevailed that the toxicity of this class of virostatics will be low because of the absence of enzymes similar to HIV protease in the human body. Unfortunately, the reality was different, and soon it turned out that compounds can interact with other molecules, particularly in the lipid metabolism and trafficking pathways. Consequently, the side effects of PIs are very frequent and often so serious that the drug toxicity may sometimes represent even a greater risk for patients than the HIV infection itself []. The presence of side effects together with the pill burden negatively influence the patient’s adherence and hence contribute to the evolution of resistance.

Taken together, inspite of the indisputeble success of the HAART and benefit to patients, new approaches to the antiviral treatment, including novel HIV PIs, are highly desirable to achieve better control of HIV infection while maintaining acceptable quality of patient’s life. Novel PIs should be developed with broad specificity against PI-resistant HIV mutants, better pharmacokinetic properties, lower toxicity, and simple dosage.

In the following contribution, we will briefly review the PIs that are currently used clinically, and we will also mention some other compounds that entered various stages of clinical testing. Subsequently, we will provide an overview of selected experimental HIV PIs targeting the enzyme active site as well as other functionally important regions, namely the protease dimerization and flap domains.

Figure 2.

The three-dimensional crystal structure of HIV PR dimer depicting mutations associated with resistance to clinically used protease inhibitors []. Mutated residues are represented with their Cα atoms (spheres) and colored in the shades of red and blue for major and minor mutations, respectively. For major mutations, the semi-transparent solvent accessible surface is also shown in red. Active site aspartates and PI darunavir bound to the active site are represented in stick models. The figure was generated using the structure of highly mutated patient derived HIV-1 PR (PDB code 3GGU []) and program PyMol [].

Table 1.

Mutations in the protease gene associated with resistance to PIs a.

| PIb | Major mutationsc | Minor mutationsd |

|---|---|---|

| Atazanavir +/- ritonavir | 50, 84, 88 | 10, 16, 20, 24, 32, 33, 34, 36, 46, 48, 53, 54, 60, 62, 64, 71, 73, 82, 85, 90, 93 |

| Darunavire | 50, 54, 76, 84 | 11, 32, 33, 47, 74, 89 |

| Fosamprenavire | 50, 84 | 10, 32, 46, 47, 54, 73, 76, 82, 90 |

| Indinavire | 46, 82, 84 | 10, 20, 24, 32, 36, 54, 71, 73, 76, 77, 90 |

| Lopinavire | 32, 47, 82 | 10, 20, 24, 33, 46, 50, 53, 54, 63, 71, 73, 76, 84, 90 |

| Nelfinavir | 30, 90 | 10, 36, 46, 71, 77, 82, 84, 88 |

| Saquinavire | 48, 90 | 10, 24, 54, 62, 71, 73, 77, 82, 84 |

| Tipranavire | 33, 47, 58, 74, 82, 84 | 10, 13, 20, 35, 36, 43, 46, 54, 69, 83, 90 |

a Adapted from International AIDS society reports [7]

b Ritonavir is not listed separately as it is currently used only as a pharmacologic booster of other PIs (in low dose).

c Major mutations are those selected first in the presence of the drug or those substantially reducing drug susceptibility.

d Minor mutations emerge later and do not have a substantial effect on virus phenotype. They may improve replication capacity of viruses containing major mutations.

e PIs used in co-formulation with ritonavir.

3. Inhibitors of HIV protease in the pipeline

Some other interesting compounds were recently or are now in various stages of clinical trials. The often convoluted history behind the development of individual compounds documents the complex requirements for the activity, resistance profile, toxicity, pharmacokinetics, and drug interactions, as well as fierce competition in the field.

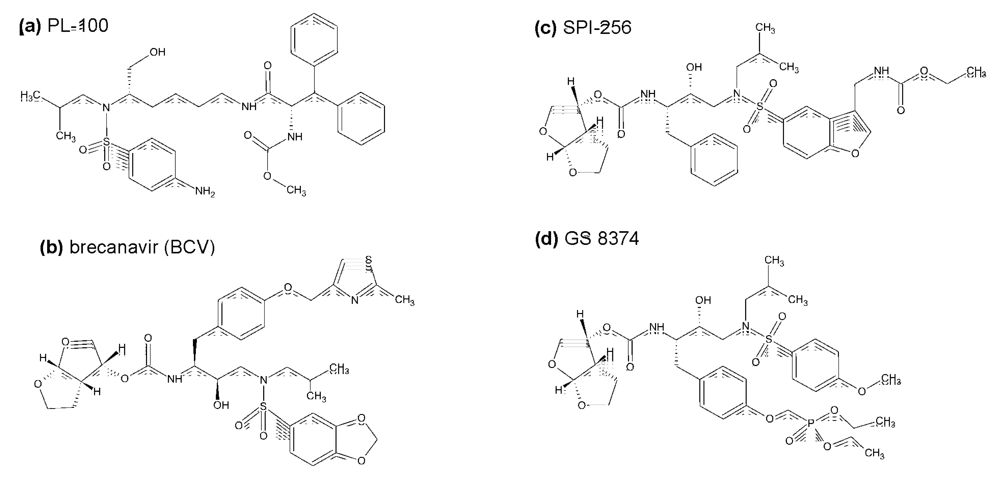

Compound PL-100, a lysine-sulfonamide inhibitor with high genetic barrier to the development of resistance and with a favorable cross-resistance profile has been developed by Ambrilia Biopharma Inc. (formerly Procyon) and licenced by Merck Co. as Mk 8122 []. The compound has been identified in a compound library based on L-lysine scaffold (Figure 5a). It is highly active against HIV PR and numerous resistant mutants and shows high genetic barrier towards the development of resistant virus strains. Moreover, it also possesses inhibitory activity against CYP450 3A4/5, which brings about the potential of using this compound in a once-daily, un-boosted regime. Crystal structure of a complex of HIV PR with a close analog of PL-100, lysine-sulfonamide 8, shows direct H-bond interactions with the flap, displacing the conserved flap water molecule []. Despite these favorable features, Merck announced in the summer of 2008 that it will put “development of PL-100 on hold and will concentrate on other PL-100 prodrugs, formulation options, and back-up compounds”.

Brecanavir (BCV, GW 640385), developed in a collaborative effort of GlaxoSmithKline and Vertex, is a tyrosyl-based arylsulfonamide protease inhibitor with relatively low binding to the plasma proteins and high affinity against a variety of PI-resistant viral species (Figure 5b). It was reported to exhibit higher in vitro potency than APV, IND, LPV, ATV, TPV, and DRV, which makes it the most potent and broadly active antiviral agent among the PIs tested in vitro []. However, in December 2006, GSK announced that it discontinued development of BCV, which was then in phase II clinical development, “due to insurmountable issues regarding formulation”.

A structure-based approach at Sequoia Pharmaceuticals, Inc. involved identification of a substructure of conserved regions in the PR active site and the design of compounds that would make optimal interactions with such a conserved substructure. The aim was to design compounds retaining high potency against a variety of PI-resistant HIV strains. This effort lead to discovery of SPI-256 (Figure 5c). This compound, currently in phase I clinical evaluation, is highly active against wild-type and multidrug-resistant HIV PRs, with inhibition constants in the picomolar range. It shows high genetic barrier, and exhibits a better resistance profile than any of the current FDA-approved compounds when analyzed using PhenoSense assay [].

GS 8374, developed at Gilead Sciences [], is based on the darunavir scaffold (more specifically, on TMC 126) with covalent attachment of a phosphonic acid moiety (Figure 5d). The phosphonate compound exhibits high affinity to HIV-1 protease, considerable antiretroviral activity, and a more favorable cross-resistance profile against clinically relevant PI-resistant HIV-1 strains. Its co-crystal structure suggests that the phosphonate group, exposed to the solvent, brings about a favorable change in the inhibitor binding entropy after the interaction with mutant enzymes via “anchoring” of the inhibitor molecule to the bulk solvent. GS 8374 showed a resistance profile superior to LPV, ATV, and DRV when assayed against a panel of highly resistant mutant viruses [].

Figure 5.

Chemical structures of inhibitors HIV protease in the pipeline.

4. Other non-peptidic HIV protease active site inhibitors

Generally, the design of novel HIV PIs includes efforts to minimize the inhibitor molecular weight, maximize its interactions with the backbone of the PR binding cleft while maintaining flexibility for better fit to the variable binding clefts of PR resistant species []. These general principles are being used by scientists from industry and academia in their efforts to design the next generation of HIV PIs.

The variability of structural motifs used by rational design or selected by library or combinatorial screening is enormous, and it is beyond the scope of this review to attempt to cover all promising compounds reported up to date. Below we will only mention several interesting recent examples, thus exemplifying the variability of approaches and of the resulting chemical structures. Even though it is questionable whether any of these compounds will ever enter the market, they still represent important contributions to the armamentarium of modern medicinal chemistry.

Favourable properties of darunavir lead to the development of several follow-up compounds, exemplified by GRL series by Ghosh et al. The P2 bis-tetrahydrofuranyl residue of darunavir was replaced by its hexahydrocyclopentafuranyl (GRL -06579A) and P2-P1’ positions of the parent structure were modified by pyrrolidinone and oxazolidinone derivatives (GRL 02031), retaining high antiviral activity and favourable resistance profile [,].

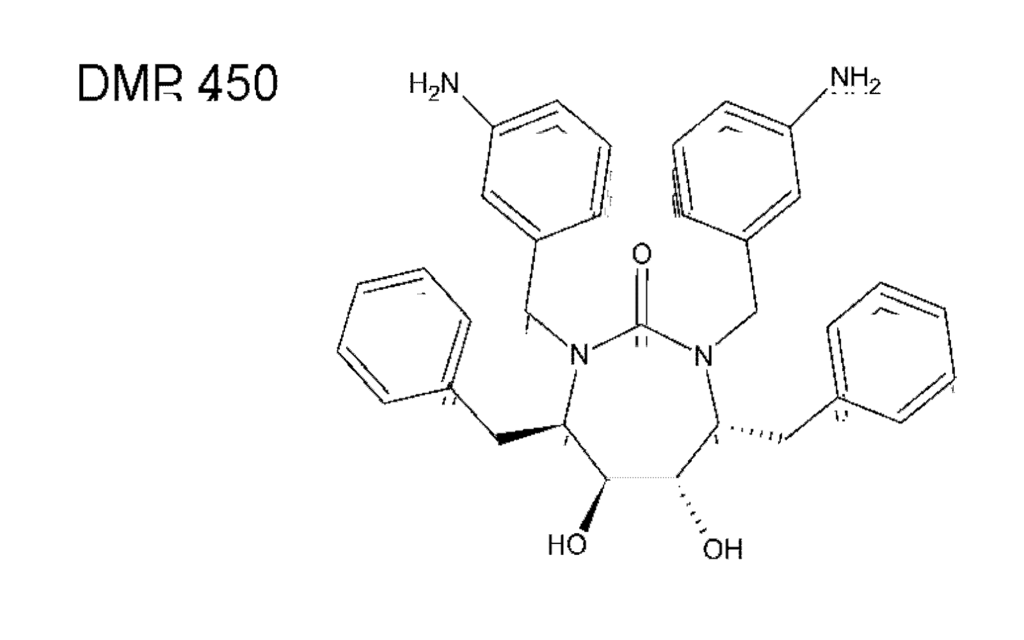

A very attractive class of compounds, cyclic ureas, was introduced in 1994 by Lam et al. []. These non-peptidic compounds were designed to include a mimic of the water molecule in the flap-proximal part of the enzyme active site. Such a water molecule was shown to interact with the main chain atoms of the closed flaps for the substrate and almost all peptidic inhibitors. Several cyclic compounds were prepared, with analogues including a seven-membered ring containing compounds DMP323 [] and DMP450 (Figure 6) []. Hallberg group in Uppsala have used carbohydrates (mannitol) as chiral precursors for the synthesis of several cyclic and C2-symmetric urea and sulfamide inhibitors [,]. Although there is currently no information about any cyclic urea-based compounds entering clinical trials, the 7-membered ring of cyclic urea is still being used as an useful scaffold for further PI design.

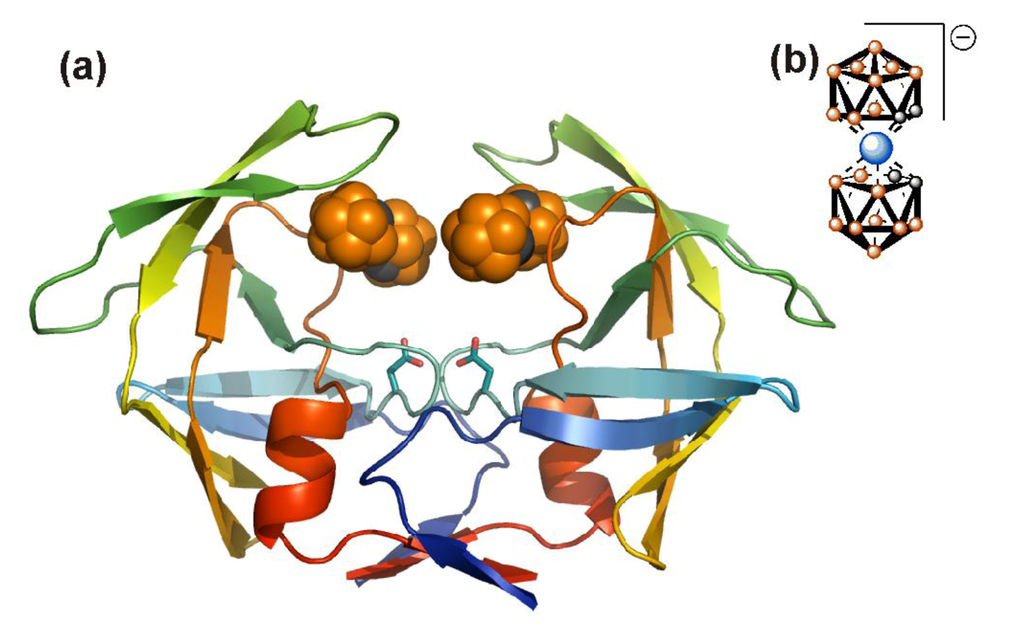

Figure 6.

Chemical structure of DMP450 (Mozenavir (DuPont).

In order to enlarge the chemical space available for the design of novel anti HIV molecules, several groups used unusual chemistry for the identification of HIV PIs. Surprisingly, even inorganic compounds, Nb-containing polyoxometalates, specifically inhibit HIV PR with submicromolar potency in tissue cultures []. In this case, the inhibitors were shown to be non-competitive and a model suggested binding to the cationic pocket on the outer surface of the flaps (see below). Clearly, the active site of HIV PR could also be targeted by compounds with unexpected chemistry. The HIV PR binding cleft was shown to accommodate C60 fullerenes, and some fullerene derivatives are indeed weak inhibitors of HIV PR []. In a search for other unconventional chemical structures that would fit into the PR binding cleft, and possess favorable pharmacologic properties, Cigler et al. [] recently identified a group of inorganic compounds, icosahedral carboranes, as promising scaffolds for PIs. Boron-containing compounds and carboranes specifically have been already utilized in medicinal chemistry in boron neutron capture therapy and in radioimaging. Such compounds are also used as stable hydrophobic pharmacophores, usually replacing bulky aromatic amino acid side chains [,]. Bis(dicarbollides) or metallacarboranes that consist of two carborane cages sandwiching the central metal atom, were shown to be specific, stable and rather potent inhibitors of HIV PR [,,]. A crystal structure revealed binding of two bis(dicarbollide) clusters to hydrophobic pockets in the flap-proximal region of the HIV PR active site, “above” the site for conventional active-site inhibitors (Figure 7). This unusual binding mode might explain the broad inhibition activity of metallacarboranes against highly PI-resistant HIV PR variants [].

Figure 7.

Crystal structure of metallacarborane inhibitor bound to HIV PR. (a) Two metallacarborane clusters bind to the flap-proximal part of the active site. The HIV PR is represented by a ribbon diagram and colored by rainbow from blue to red (N- to C- termini), the atoms of the metallacarborane cluster are represented by spheres and colored orange for boron atoms, gray for carbon atoms, and blue for cobalt. The structural formula is depicted in (b). Hydrogens are omitted for clarity.

In order to rationalize the design of new generation PIs, Schiffer and coworkers introduced an interesting approach (recently reviewed in []). They proposed that a structural space within the HIV PR binding cleft, defined by a consensus volume occupied by the natural substrates of the enzyme, should represent a spatial constraint for the inhibitor design. If the inhibitor binds within this “substrate envelope”, which was identified by a series of detailed structural analyses of enzyme-substrate complexes [], then its activity should not be significantly compromised by mutations in the PR binding cleft. Any mutation within the “substrate envelope” would necessarily lead to a substrate binding defect. This approach has been tested on a series of compounds based on amprenavir structure and designed to fit within the substrate envelope. Some of these compounds exhibited picomolar inhibitory constants against a panel of multi-resistant HIV PR variants [].

5. Alternative HIV protease inhibitors targeting functional domains outside the enzyme active site

Several HIV PR regions have been identified that seem to be conserved in all examined HIV sequences derived from treatment-naïve patients. They include residues 1-9 and 94-99 (N- and C- termini), 21-32 (active site core), 47-56 (flap region) and 78-88 (substrate-binding region) []. Although the resistant mutations could clearly evolve even in these conserved regions (especially in the flap and substrate-binding region), it is tempting to suggest that compounds binding conservative domains of the enzyme outside the active site might be “resistance-repellent”. Moreover, inhibitors targeted to the domains outside the active cleft might show a synergistic effect to the conventional active-site targeted compounds. Finally, blocking an earlier event in the maturation pathway of the virus, such as HIV PR dimerization by binding Gag-Pol polyprotein prior viral maturation, might be an attractive approach for antiviral therapy. The alternative inhibitor designs have not, as yet, yielded any successful drugs. However, the approaches and techniques developed for their creation could be proven useful in the future, or in design of inhibitors of other targets.

5.1. HIV PR dimerization inhibitors

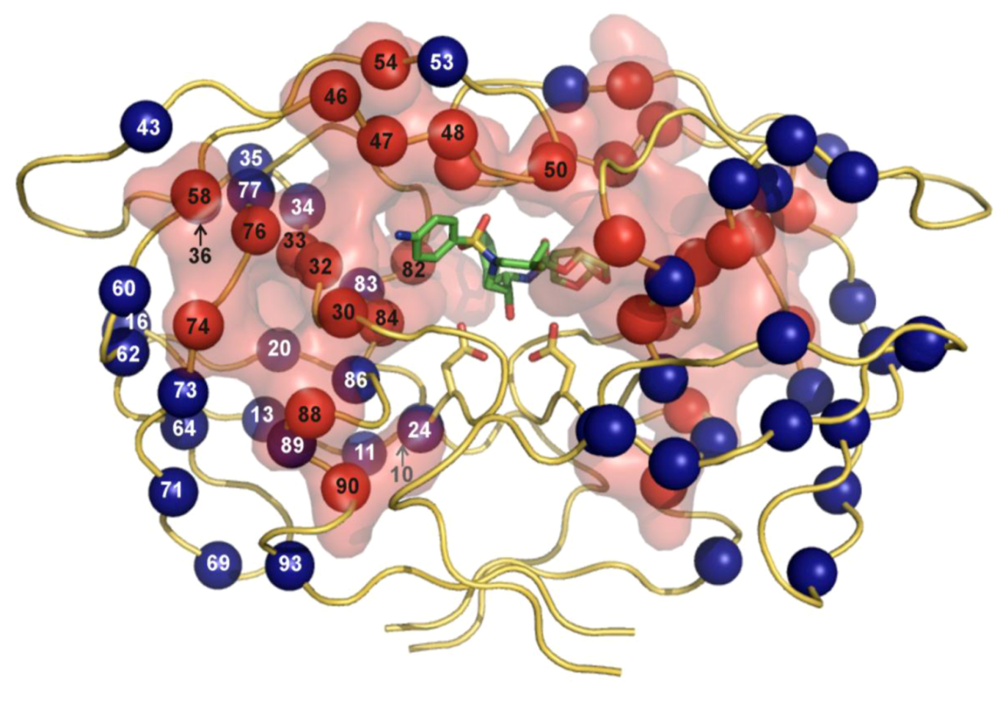

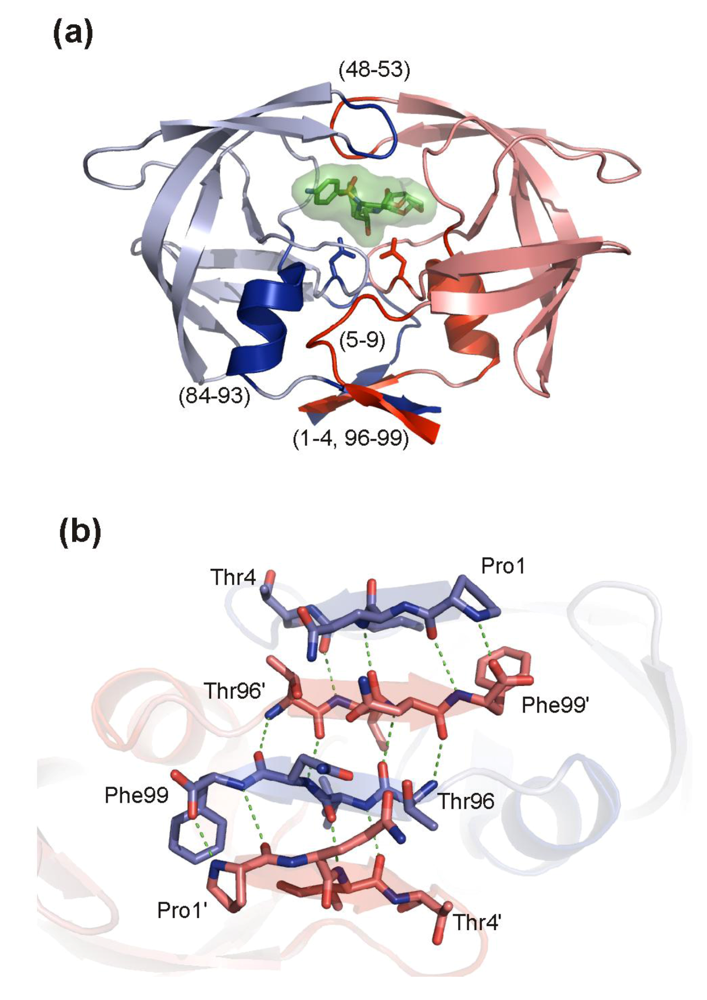

HIV PR is only active as a dimer in which each of the two catalytic aspartates is contributed by one monomer. The determination of the dimer dissociation constant (Kd)has been the goal of considerable efforts of many groups, but its value differs substantially depending on the various techniques and experimental conditions (reviewed in []). The reported Kd values from kinetic studies are typically of the order of 10−7 to 10−9 M, whereas the values derived from sedimentation analysis are on average three orders of magnitude lower []. It was already suggested in 1990 that blocking the dimerization of the protease monomers could be an effective means for inactivating the enzyme []. The crystal structure of HIV-1 protease [] shows that the enzyme dimerization interface is formed by the β-hairpin of the two flaps, catalytic triad, helices (residues 84-93) interacting with residues 4-10, and N- and C-terminal β-strands (Figure 8a). A four-stranded antiparallel β-sheet composed of the two N‑termini (residues 1-4) interdigitating the two C-termini (residues 96-99) (Figure 8b) contributes to 75% of the stabilizing energy []. This dimeric interface is conserved among most HIV-1 isolates and drug-resistant variants (see Figure 2) and thus represents an attractive target for development of ligands preventing dimerization.

Early studies demonstrated that interface peptides reproducing the native sequence of C-terminal and N-terminal fragments act as HIV PR dimerization inhibitors, although in micromolar concentration [,,]. Connection of the N- and C- terminal peptides with flexible linkers [,] or more rigid scaffolds (“molecular tongs“) [,] further increased their inhibitory potency. A recent study describes novel interfacial peptides tethered through their side chains, with inhibitory potencies against the wild-type HIV PR being in low nanomolar range [].

Figure 8. HIV PR dimerization interface. (a) The overall structure of the HIV PR dimer with an inhibitor bound in the active site. Monomers are colored blue and red, respectively. Regions involved in creation of a dimeric interface are highlighted by darker shades and indicated by residue numbers. (b) A detail of the four-stranded antiparallel β-sheet formed by interdigitation of C- and N-terminal strands. Monomers are colored blue and red, respectively. A hydrogen bonding network is represented by green dashed lines. The figure was generated using the structure of highly mutated, patient derived HIV-1 PR (PDB code 3GGU []) and program PyMol [].

Figure 8.

Modification of the termini of an interfacial peptide by attachment of a lipophilic group and alkyl chains (e.g., palmitoyl) improves both the inhibitory capacity and the specificity [,]. Currently, the most potent lipopeptide inhibitors, containing the minimal peptide sequence Leu-Glu-Tyr modified on the N-terminus by palmitoyl, attained sub-nanomolar Ki values for the in vitro inhibition of the wild type and drug-resistant mutant variants []. Irreversible inhibitors, in which the interface peptide is able to covalently modify the protein dimeric interface through a disulfide bridge with Cys95, have also been described [].

Interesting macromolecular inhibitors targeting dimerization domains are fusions of the N-terminal HIV-1 PR peptide with a cell permeable domain from HIV-1 Tat [,]. Also, an antibody recognizing the N terminus of HIV PR (residues 1-7), which inhibits activity of both HIV-1 and HIV-2 proteases with Ki values in low nano-molar range [,], has been reported. The use of the antibody as an anti-HIV drug is rather limited, nevertheless its structure [,] might be used as a lead in design of low-molecular mimics.

There has been a significant effort to develop dimerization inhibitors of HIV PR and characterize their binding on a structural level []. Also, there is great interest to develop inhibitors targeting protein-protein interfaces in enzymes and other proteins. Several protein–protein interfaces indeed became targets for successful drug development, e.g., HIV proteins and intracellular co-factors [], HIV capsid assembly (reviewed in []) or herpes virus protease dimerization []. These advances might positively boost the development of new HIV PR dimerization inhibitors [].

5.2. Inhibitors targeting HIV PR flaps

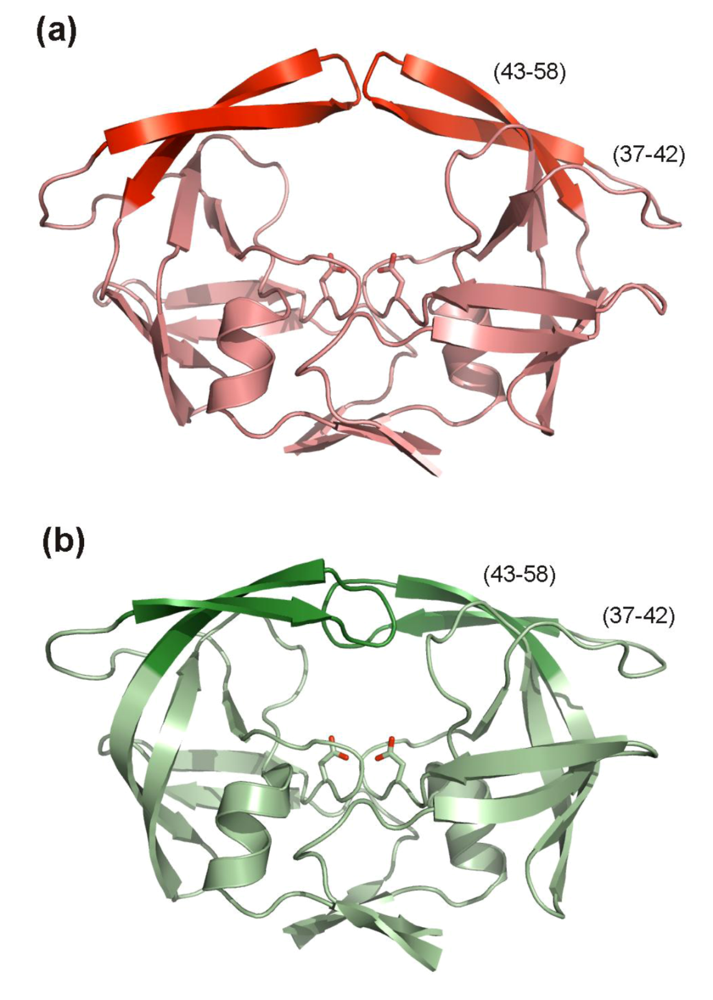

Residues 43-58 of HIV PR form an anti-parallel β-hairpin referred to as “the flap”. Two flaps within a dimer cover the active site cavity and their movement is crucial for binding and release of protease substrate. The conformation behavior of this glycine rich region has been extensively studied [,] and the most populated states are closed and semi-open. The closed state is found when a substrate or peptidomimetic inhibitor is bound to the active site (Figure 9b) while the semi-open conformation is most prevalent in the enzyme apo-form (Figure 9a). Since all currently approved FDA PIs target the closed conformation, developing of inhibitors targeted to the open flap conformation with a different binding mode might be an alternative to circumvent the cross-resistance.

Recent examples of inhibitors targeting the open-flap conformation are metallacarborane-based [] and pyrrolidine-based [] compounds. The metallacarboranes described earlier in this review bind to the flap-proximal part of the enzyme active site without interaction with the catalytic aspartates, while the pyrrolidine diester inhibitors target the catalytic dyad.

The region preceding the flap in the sequence (residues 34-42) is called the flap elbow (or the hinge). It folds into a surface exposed loop with no particular secondary structure which undergoes substantial change during flap opening and closing (Figure 9). With the exception of an insertion in position 35 [], no resistance mutations are associated with this region (Figure 2, Table 1). The flap elbow thus might represent a promising drug target.

A monoclonal antibody recognizing an epitope corresponding to residues 36-46 inhibits the activity of HIV PR with Ki value in a nanomolar range []. The proposed inhibition mechanism based on the crystal structure of the antibody fragment in complex with the 36-46 epitope peptide postulates that antibody binding prevents flap closure over the active site []. An example of another inhibitory compound with predicted affinity toward the flap elbow are Nb-containing polyoxometalates [], mentioned above. They inhibit HIV PR with Ki values in a low-nanomolar range and exhibit a non-competitive mode with stoichiometry 2 inhibitors to 1 PR dimer. Computational studies suggested that these compounds bind to a cationic pocket formed by residues Lys41, Lys43, and Lys55.

Figure 9.

HIV PR flap conformations. (a) Overall structure of the apo-form of the HIV PR. The flaps (residues 43-58) in semi-open conformation are highlighted in red, residues 37-42, so called flap elbows are also indicated. The figure was generated using the structure of free HIV-1 PR (PDB code 1HHP []) and program PyMol []. (b) Overall structure of the HIV PR with flaps (in dark green) in closed conformation. Residues 37-42, so called flap elbows are also indicated. Inhibitor bound in the enzyme active site is omitted from the figure. The figure was generated using the structure of a highly mutated patient derived HIV-1 PR (PDB code 3GGU []) and program PyMol [].

6. Conclusions

Development and clinical application of specific inhibitors of HIV PR almost immediately after the identification of HIV PR as a valid pharmaceutical target represents fascinating and, indeed, probably the most successful example of rational drug design in the history of biomedicine. There are currently nine FDA approved PIs available. In developed countries the protease inhibitors have at present time a secure position in the therapeutic armamentarium for both the initial therapy and the second-line and salvage treatment. It is also highly probable, that they will keep this position with further development of new more effective and less toxic molecules in the future []. Because of their high costs, protease inhibitors are in the resource-limited settings used mainly as drugs of the second-line therapy, but in the future an increase of their use can be certainly expected [].

There is continuous need for the development of safer, cheaper drugs, active against the host of multi-resistant HIV species stemming from different virus strains, with high antiviral activity, excellent pharmacokinetic properties and little off-target activity, imposing low pill burden and little side-effect to the patient. Even if such an ideal drug never materializes, the research on HIV PR and its inhibition will continue to provide remarkable wealth of information about ligand-enzyme and protein-protein interactions, structural plasticity of proteins, mechanism of resistance development, pharmacokinetics of a chemotherapeutic in individual compartments of the body, etc. All this information could be used (and, indeed, is already being used) for the development of other compounds targeted against other pathogens, other enzymes and other, seemingly indomitable human diseases.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Devon Maloy for critical proofreading of the manuscript, Milan Kožíšek for help with the preparation of figures and numerous colleagues (namely Ron M. Kagan, Tomas Cihlar, Sergei Gulnik and Alex Wlodawer) for sharing unpublished information and very useful critical comments. The research on HIV protease inhibition and structure in the laboratory of J.K. and P.R. is funded by Ministry of Education of the Czech Republic under program 1M0508, by the Grant Agency of the Academy of Science of the Czech Republic (IAAX00320901) and by the 6th Framework of the European Union (HIV PI resistance, contract No. 03769).

References

- Kohl, N.E.; Emini, E.A.; Schleif, W.A.; Davis, L.J.; Heimbach, J.C.; Dixon, R.A.; Scolnick, E.M.; Sigal, I.S. Active human immunodeficiency virus protease is required for viral infectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 1988, 85, 4686–4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winters, M.A.; Merigan, T.C. Insertions in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease and reverse transcriptase genes: clinical impact and molecular mechanisms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 2575–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozisek, M.; Saskova, K.G.; Rezacova, P.; Brynda, J.; van Maarseveen, N.M.; de Jong, D.; Boucher, C.A.; Kagan, R.M.; Nijhuis, M.; Konvalinka, J. Ninety-nine is not enough: molecular characterization of inhibitor-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease mutants with insertions in the flap region. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 5869–5878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyon, L.; Croteau, G.; Thibeault, D.; Poulin, F.; Pilote, L.; Lamarre, D. Second locus involved in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to protease inhibitors. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 3763–3769. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mammano, F.; Petit, C.; Clavel, F. Resistance-associated loss of viral fitness in human immunodeficiency virus type 1: phenotypic analysis of protease and gag coevolution in protease inhibitor-treated patients. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 7632–7637. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nijhuis, M.; van Maarseveen, N.M.; Lastere, S.; Schipper, P.; Coakley, E.; Glass, B.; Rovenska, M.; de Jong, D.; Chappey, C.; Goedegebuure, I.W.; Heilek-Snyder, G.; Dulude, D.; Cammack, N.; Brakier-Gingras, L.; Konvalinka, J.; Parkin, N.; Krausslich, H.G.; Brun-Vezinet, F.; Boucher, C. A. A novel substrate-based HIV-1 protease inhibitor drug resistance mechanism. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, V.A.; Brun-Vezinet, F.; Clotet, B.; Gunthard, H.F.; Kuritzkes, D.R.; Pillay, D.; Schapiro, J.M.; Richman, D.D. Update of the Drug Resistance Mutations in HIV-1. Top HIV Med. 2008, 16, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saskova, K.G.; Kozisek, M.; Rezacova, P.; Brynda, J.; Yashina, T.; Kagan, R.M.; Konvalinka, J. Molecular characterization of clinical isolates of human immunodeficiency virus resistant to the protease inhibitor darunavir. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 8810–8818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLano, W.L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System . DeLano Scientific: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, D.; Reiss, P.; Mallal, S. Adverse effects of antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection: a review of selected topics. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2005, 4, 201–218. [Google Scholar]

- Shibuyama, S.; Gevorkyan, A.; Yoo, U.; Tim, S.; Dzhangiryan, K.; Scott, J. Understanding and avoiding antiretroviral adverse events. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2006, 12, 1075–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wohl, D.; McComsey, G.; Tebas, P.; Brown, T.; Glesby, M.; Reeds, D.; Shikuma, C.; Mulligan, K.; Dube, M.; Wininger, D.; Huang, J.; Revuelta, M.; Currier, J.; Swindells, S.; Fichtenbaum, C.; Basar, M.; Tungsiripat, M.; Meyer, W.; Weihe, J.; Wanke, C. Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of metabolic complications of HIV infection and its therapy. Clin. Infect Dis. 2006, 43, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wlodawer, A.; Vondrasek, J. Inhibitors of HIV-1 protease: a major success of structure-assisted drug design. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1998, 27, 249–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wlodawer, A. Rational approach to AIDS drug design through structural biology. Annu. Rev. Med. 2002, 53, 595–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prejdova, J.; Soucek, M.; Konvalinka, J. Determining and overcoming resistance to HIV protease inhibitors. Curr. Drug Targets Infect. Disord. 2004, 4, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Clercq, E. New approaches toward anti-HIV chemotherapy. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 1297–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, P.D.; Das, D.; Mitsuya, H. Overcoming HIV drug resistance through rational drug design based on molecular, biochemical, and structural profiles of HIV resistance. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2006, 63, 1706–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastrolorenzo, A.; Rusconi, S.; Scozzafava, A.; Barbaro, G.; Supuran, C.T. Inhibitors of HIV-1 protease: current state of the art 10 years after their introduction. From antiretroviral drugs to antifungal, antibacterial and antitumor agents based on aspartic protease inhibitors. Curr. Med. Chem. 2007, 14, 2734–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Clercq, E. The history of antiretrovirals: key discoveries over the past 25 years. Rev. Med. Virol. 2009, 19, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.; Schiffer, C.A.; Lee, S.K.; Swanstrom, R. Viral protease inhibitors. In Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Kräusslich, H.G., Bartenschlager, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 189, pp. 85–110. [Google Scholar]

- Gulnik, S.V.; Afonina, E.; Eissenstaat, M. HIV-1 protease inhibitors as antiretroviral agents. Lu, C., Li, A.P., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons, Inc, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Witvrouw, M.; Pannecouque, C.; Switzer, W.M.; Folks, T.M.; de Clercq, E.; Heneine, W. Susceptibility of HIV-2, SIV and SHIV to various anti-HIV-1 compounds: implications for treatment and postexposure prophylaxis. Antivir. Ther. 2004, 9, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mallewa, J.E.; Wilkins, E.; Vilar, J.; Mallewa, M.; Doran, D.; Back, D.; Pirmohamed, M. HIV-associated lipodystrophy: a review of underlying mechanisms and therapeutic options. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008, 62, 648–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbaro, G.; Iacobellis, G. Metabolic syndrome associated with HIV and highly active antiretroviral therapy. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2009, 9, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flint, O.P.; Noor, M.A.; Hruz, P.W.; Hylemon, P.B.; Yarasheski, K.; Kotler, D.P.; Parker, R.A.; Bellamine, A. The role of protease inhibitors in the pathogenesis of HIV-associated lipodystrophy: cellular mechanisms and clinical implications. Toxicol. Pathol. 2009, 37, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duvivier, C.; Kolta, S.; Assoumou, L.; Ghosn, J.; Rozenberg, S.; Murphy, R.L.; Katlama, C.; Costagliola, D. Greater decrease in bone mineral density with protease inhibitor regimens compared with nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor regimens in HIV-1 infected naive patients. AIDS 2009, 27, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polli, J.W.; Jarrett, J.L.; Studenberg, S.D.; Humphreys, J.E.; Dennis, S.W.; Brouwer, K.R.; Woolley, J.L. Role of P-glycoprotein on the CNS disposition of amprenavir (141W94), an HIV protease inhibitor. Pharm. Res. 1999, 16, 1206–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nath, A.; Sacktor, N. Influence of highly active antiretroviral therapy on persistence of HIV in the central nervous system. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2006, 19, 358–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwara, A.; Delong, A.; Rezk, N.; Hogan, J.; Burtwell, H.; Chapman, S.; Moreira, C.C.; Kurpewski, J.; Ingersoll, J.; Caliendo, A.M.; Kashuba, A.; Cu-Uvin, S. Antiretroviral drug concentrations and HIV RNA in the genital tract of HIV-infected women receiving long-term highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin. Infec. Dis. 2008, 46, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, S.H.; Wensing, A.M.; Droste, J.A.; ten Kate, R.W.; Jurriaans, S.; Burger, D.M.; Borleffs, J.C.; Lange, J.M.; Prins, J.M. No virological failure in semen during properly suppressive antiretroviral therapy despite subtherapeutic local drug concentrations. HIV Clin Trials 2006, 7, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallant, J.E. Protease-inhibitor boosting in the treatment-experienced patient. AIDS Rev. 2004, 6, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Desai, M.C. Pharmacokinetic enhancers for HIV drugs. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2009, 10, 775–786. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Youle, M. Overview of boosted protease inhibitors in treatment-experienced HIV-infected patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007, 60, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winston, A.; Boffito, M. The management of HIV-1 protease inhibitor pharmacokinetic interactions. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2005, 56, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, N.A.; Martin, J.A.; Kinchington, D.; Broadhurst, A.V.; Craig, J.C.; Duncan, I.B.; Galpin, S.A.; Handa, B.K.; Kay, J.; Krohn, A.; et al. Rational design of peptide-based HIV proteinase inhibitors. Science 1990, 248, 358–361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kilby, J.M.; Sfakianos, G.; Gizzi, N.; Siemon-Hryczyk, P.; Ehrensing, E.; Oo, C.; Buss, N.; Saag, M. S. Safety and pharmacokinetics of once-daily regimens of soft-gel capsule saquinavir plus minidose ritonavir in human immunodeficiency virus-negative adults. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 2672–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, C.M.; Noble, S. Saquinavir soft-gel capsule formulation. A review of its use in patients with HIV infection. Drugs 1998, 55, 461–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempf, D.J.; Marsh, K.C.; Fino, L.C.; Bryant, P.; Craig-Kennard, A.; Sham, H.L.; Zhao, C.; Vasavanonda, S.; Kohlbrenner, W.E.; Wideburg, N.E.; et al. Design of orally bioavailable, symmetry-based inhibitors of HIV protease. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1994, 2, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyle, G.J.; Back, D. Principles and practice of HIV-protease inhibitor pharmacoenhancement. HIV Med. 2001, 2, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsey, B.D.; Levin, R.B.; McDaniel, S.L.; Vacca, J.P.; Guare, J.P.; Darke, P.L.; Zugay, J.A.; Emini, E.A.; Schleif, W.A.; Quintero, J.C.; et al. L-735,524: the design of a potent and orally bioavailable HIV protease inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 1994, 37, 3443–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadler, R.B.; Rubenstein, J.N.; Eggener, S.E.; Loor, M.M.; Smith, N.D. The etiology of urolithiasis in HIV infected patients. J. Urol. 2003, 169, 475–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capaldini, L. Protease inhibitors' metabolic side effects: cholesterol, triglycerides, blood sugar, and "Crix belly." Interview with Lisa Capaldini, Interview by John S. James. AIDS Treat. News 1997, 277, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Patick, A.K.; Mo, H.; Markowitz, M.; Appelt, K.; Wu, B.; Musick, L.; Kalish, V.; Kaldor, S.; Reich, S.; Ho, D.; Webber, S. Antiviral and resistance studies of AG1343, an orally bioavailable inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus protease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996, 40, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kozisek, M.; Bray, J.; Rezacova, P.; Saskova, K.; Brynda, J.; Pokorna, J.; Mammano, F.; Rulisek, L.; Konvalinka, J. Molecular analysis of the HIV-1 resistance development: enzymatic activities, crystal structures, and thermodynamics of nelfinavir-resistant HIV protease mutants. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 374, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardsley-Elliot, A.; Plosker, G.L. Nelfinavir: an update on its use in HIV infection. Drugs 2000, 59, 581–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.E.; Baker, C.T.; Dwyer, M.D.; Murcko, M.A.; Rao, B.G.; Tung, R.D.; Navia, M.A. Crystal structure of HIV-1 protease in complex with VX-478, a potent and orally bioavailable inhibitor of the enzyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 1181–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, M.F.; Guinea, R.; Griffin, P.; Macmanus, S.; Elston, R.C.; Wolfram, J.; Richards, N.; Hanlon, M.H.; Porter, D.J.; Wrin, T.; Parkin, N.; Tisdale, M.; Furfine, E.; Petropoulos, C.; Snowden, B.W.; Kleim, J.P. Changes in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag at positions L449 and P453 are linked to I50V protease mutants in vivo and cause reduction of sensitivity to amprenavir and improved viral fitness in vitro. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 7398–7406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dube, M.P.; Qian, D.; Edmondson-Melancon, H.; Sattler, F.R.; Goodwin, D.; Martinez, C.; Williams, V.; Johnson, D.; Buchanan, T.A. Prospective, intensive study of metabolic changes associated with 48 weeks of amprenavir-based antiretroviral therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 35, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adkins, J.C.; Faulds, D. Amprenavir. Drugs 1998, 55, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floridia, M.; Bucciardini, R.; Fragola, V.; Galluzzo, C.M.; Giannini, G.; Pirillo, M.F.; Amici, R.; Andreotti, M.; Ricciardulli, D.; Tomino, C.; Vella, S. Risk factors and occurrence of rash in HIV-positive patients not receiving nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor: data from a randomized study evaluating use of protease inhibitors in nucleoside-experienced patients with very low CD4 levels (<50 cells/microL). HIV Med. 2004, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vierling, P.; Greiner, J. Prodrugs of HIV protease inhibitors. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2003, 9, 1755–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, H.A.; Arduino, R.C. Fosamprenavir calcium plus ritonavir for HIV infection. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2007, 5, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sham, H.L.; Kempf, D.J.; Molla, A.; Marsh, K.C.; Kumar, G.N.; Chen, C.M.; Kati, W.; Stewart, K.; Lal, R.; Hsu, A.; Betebenner, D.; Korneyeva, M.; Vasavanonda, S.; McDonald, E.; Saldivar, A.; Wideburg, N.; Chen, X.; Niu, P.; Park, C.; Jayanti, V.; Grabowski, B.; Granneman, G.R.; Sun, E.; Japour, A.J.; Leonard, J.M.; Plattner, J.J.; Norbeck, D.W. ABT-378, a highly potent inhibitor of the human immunodeficiency virus protease. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998, 42, 3218–3224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kempf, D.J.; Isaacson, J.D.; King, M.S.; Brun, S.C.; Xu, Y.; Real, K.; Bernstein, B.M.; Japour, A.J.; Sun, E.; Rode, R.A. Identification of genotypic changes in human immunodeficiency virus protease that correlate with reduced susceptibility to the protease inhibitor lopinavir among viral isolates from protease inhibitor-experienced patients. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 7462–7469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo, A.; Stewart, K.D.; Sham, H.L.; Norbeck, D.W.; Kohlbrenner, W.E.; Leonard, J.M.; Kempf, D.J.; Molla, A. In vitro selection and characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants with increased resistance to ABT-378, a novel protease inhibitor. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 7532–7541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- de Mendoza, C.; Valer, L.; Bacheler, L.; Pattery, T.; Corral, A.; Soriano, V. Prevalence of the HIV-1 protease mutation I47A in clinical practice and association with lopinavir resistance. AIDS 2006, 20, 1071–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saskova, K.G.; Kozisek, M.; Lepsik, M.; Brynda, J.; Rezacova, P.; Vaclavikova, J.; Kagan, R.M.; Machala, L.; Konvalinka, J. Enzymatic and structural analysis of the I47A mutation contributing to the reduced susceptibility to HIV protease inhibitor lopinavir. Protein Sci. 2008, 17, 1555–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masse, S.; Lu, X.; Dekhtyar, T.; Lu, L.; Koev, G.; Gao, F.; Mo, H.; Kempf, D.; Bernstein, B.; Hanna, G.J.; Molla, A. In vitro selection and characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 with decreased susceptibility to lopinavir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 3075–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagan, R.M.; Shenderovich, M.D.; Heseltine, P.N.; Ramnarayan, K. Structural analysis of an HIV-1 protease I47A mutant resistant to the protease inhibitor lopinavir. Protein Sci. 2005, 14, 1870–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvetkovic, R.S.; Goa, K.L. Lopinavir/ritonavir: a review of its use in the management of HIV infection. Drugs 2003, 63, 769–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bold, G.; Fassler, A.; Capraro, H.G.; Cozens, R.; Klimkait, T.; Lazdins, J.; Mestan, J.; Poncioni, B.; Rosel, J.; Stover, D.; Tintelnot-Blomley, M.; Acemoglu, F.; Beck, W.; Boss, E.; Eschbach, M.; Hurlimann, T.; Masso, E.; Roussel, S.; Ucci-Stoll, K.; Wyss, D.; Lang, M. New aza-dipeptide analogues as potent and orally absorbed HIV-1 protease inhibitors: candidates for clinical development. J. Med. Chem. 1998, 41, 3387–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Tiec, C.; Barrail, A.; Goujard, C.; Taburet, A.M. Clinical pharmacokinetics and summary of efficacy and tolerability of atazanavir. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2005, 44, 1035–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poppe, S.M.; Slade, D.E.; Chong, K.T.; Hinshaw, R.R.; Pagano, P.J.; Markowitz, M.; Ho, D.D.; Mo, H.; Gorman, R.R.; Dueweke, T.J.; Thaisrivongs, S.; Tarpley, W.G. Antiviral activity of the dihydropyrone PNU-140690, a new nonpeptidic human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997, 41, 1058–1063. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Muzammil, S.; Armstrong, A.A.; Kang, L.W.; Jakalian, A.; Bonneau, P.R.; Schmelmer, V.; Amzel, L.M.; Freire, E. Unique thermodynamic response of tipranavir to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease drug resistance mutations. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 5144–5154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larder, B.A.; Hertogs, K.; Bloor, S.; van den Eynde, C.H.; DeCian, W.; Wang, Y.; Freimuth, W.W.; Tarpley, G. Tipranavir inhibits broadly protease inhibitor-resistant HIV-1 clinical samples. AIDS 2000, 14, 1943–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plosker, G.L.; Figgitt, D.P. Tipranavir. Drugs 2003, 63, 1611–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macias, J.; Orihuela, F.; Rivero, A.; Viciana, P.; Marquez, M.; Portilla, J.; Rios, M.J.; Munoz, L.; Pasquau, J.; Castano, M.A.; Abdel-Kader, L.; Pineda, J.A. Hepatic safety of tipranavir plus ritonavir (TPV/r)-based antiretroviral combinations: effect of hepatitis virus co-infection and pre-existing fibrosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2009, 63, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbuthnot, C.; Wilde, J.T. Increased risk of bleeding with the use of tipranavir boosted with ritonavir in haemophilic patients. Haemophilia 2008, 14, 140–141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed][Green Version]

- King, J.R.; Acosta, E.P. Tipranavir: a novel nonpeptidic protease inhibitor of HIV. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2006, 45, 665–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, Y.; Nakata, H.; Maeda, K.; Ogata, H.; Bilcer, G.; Devasamudram, T.; Kincaid, J.F.; Boross, P.; Wang, Y.F.; Tie, Y.; Volarath, P.; Gaddis, L.; Harrison, R.W.; Weber, I.T.; Ghosh, A.K.; Mitsuya, H. Novel bis-tetrahydrofuranylurethane-containing nonpeptidic protease inhibitor (PI) UIC-94017 (TMC114) with potent activity against multi-PI-resistant human immunodeficiency virus in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 2003, 47, 3123–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabu-Jeyabalan, M.; Nalivaika, E.; Schiffer, C.A. How does a symmetric dimer recognize an asymmetric substrate? A substrate complex of HIV-1 protease. J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 301, 1207–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chellappan, S.; Kiran Kumar Reddy, G.S.; Ali, A.; Nalam, M.N.; Anjum, S.G.; Cao, H.; Kairys, V.; Fernandes, M.X.; Altman, M.D.; Tidor, B.; Rana, T.M.; Schiffer, C.A.; Gilson, M.K. Design of mutation-resistant HIV protease inhibitors with the substrate envelope hypothesis. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2007, 69, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefebvre, E.; Schiffer, C.A. Resilience to resistance of HIV-1 protease inhibitors: profile of darunavir. AIDS Rev 2008, 10, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kovalevsky, A.Y.; Liu, F.; Leshchenko, S.; Ghosh, A.K.; Louis, J.M.; Harrison, R.W.; Weber, I.T. Ultra-high resolution crystal structure of HIV-1 protease mutant reveals two binding sites for clinical inhibitor TMC114. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 363, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovalevsky, A.Y.; Ghosh, A.K.; Weber, I.T. Solution kinetics measurements suggest HIV-1 protease has two binding sites for darunavir and amprenavir. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 6599–6603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, Y.; Matsumi, S.; Das, D.; Amano, M.; Davis, D.A.; Li, J.; Leschenko, S.; Baldridge, A.; Shioda, T.; Yarchoan, R.; Ghosh, A.K.; Mitsuya, H. Potent inhibition of HIV-1 replication by novel non-peptidyl small molecule inhibitors of protease dimerization. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 28709–28720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, N.M.; Prabu-Jeyabalan, M.; Nalivaika, E.A.; Wigerinck, P.; de Bethune, M.P.; Schiffer, C.A. Structural and thermodynamic basis for the binding of TMC114, a next-generation human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitor. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 12012–12021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dierynck, I.; Keuleers, I.; de Wit, M.; Tahri, A.; Surleraux, D.L.; Peeters, A.; Hertogs, K. Kinetic characterization of the potent activity of TMC114 on wild-type HIV-1 protease. Abstracts of 14th International HIV Drug Resistance Workshop 2005, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Clotet, B.; Bellos, N.; Molina, J.M.; Cooper, D.; Goffard, J.C.; Lazzarin, A.; Wohrmann, A.; Katlama, C.; Wilkin, T.; Haubrich, R.; Cohen, C.; Farthing, C.; Jayaweera, D.; Markowitz, M.; Ruane, P.; Spinosa-Guzman, S.; Lefebvre, E. Efficacy and safety of darunavir-ritonavir at week 48 in treatment-experienced patients with HIV-1 infection in POWER 1 and 2: a pooled subgroup analysis of data from two randomised trials. Lancet 2007, 369, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madruga, J.V.; Berger, D.; McMurchie, M.; Suter, F.; Banhegyi, D.; Ruxrungtham, K.; Norris, D.; Lefebvre, E.; de Bethune, M.P.; Tomaka, F.; de Pauw, M.; Vangeneugden, T.; Spinosa-Guzman, S. Efficacy and safety of darunavir-ritonavir compared with that of lopinavir-ritonavir at 48 weeks in treatment-experienced, HIV-infected patients in TITAN: a randomised controlled phase III trial. Lancet 2007, 370, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Meyer, S.; Dierynck, I.; Lathouwers, E.; Van Baelen, B.; Vangeneugden T.; Spinosa-Guzman, S.; Peeters, M.; Picchio, G.; Bethune, M. P. Phenotypic and genotypic determinants of resistance to darunavir: analysis of data from treatment-experienced patients in POWER 1,2,3 and DUET-1 and 2 . Antivir. Ther. 2008, 13, A33. [Google Scholar]

- McKeage, K.; Perry, C.M.; Keam, S.J. Darunavir: a review of its use in the management of HIV infection in adults. Drugs 2009, 69, 477–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dandache, S.; Sevigny, G.; Yelle, J.; Stranix, B.R.; Parkin, N.; Schapiro, J.M.; Wainberg, M.A.; Wu, J.J. In vitro antiviral activity and cross-resistance profile of PL-100, a novel protease inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 4036–4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalam, M.N.; Peeters, A.; Jonckers, T.H.; Dierynck, I.; Schiffer, C.A. Crystal structure of lysine sulfonamide inhibitor reveals the displacement of the conserved flap water molecule in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 9512–9518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazen, R.; Harvey, R.; Ferris, R.; Craig, C.; Yates, P.; Griffin, P.; Miller, J.; Kaldor, I.; Ray, J.; Samano, V.; Furfine, E.; Spaltenstein, A.; Hale, M.; Tung, R.; St Clair, M.; Hanlon, M.; Boone, L. In vitro antiviral activity of the novel, tyrosyl-based human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 protease inhibitor brecanavir (GW640385) in combination with other antiretrovirals and against a panel of protease inhibitor-resistant HIV. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 3147–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wynne, B.; Holland, A.; Ruff, D.; Guttendorf, R. A First-in-Human Study Evaluating the Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics (PK) of SPI-256, a Novel HIV Protease Inhibitor (PI),Administered Alone and in Combination with Ritonavir (RTV) in HealthyAdult Subjects. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cihlar, T.; He, G.X.; Liu, X.; Chen, J.M.; Hatada, M.; Swaminathan, S.; McDermott, M.J.; Yang, Z.Y.; Mulato, A.S.; Chen, X.; Leavitt, S.A.; Stray, K.M.; Lee, W.A. Suppression of HIV-1 protease inhibitor resistance by phosphonate-mediated solvent anchoring. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 363, 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callebaut, C.; Stray, K.; Tsai, L.; Xu, L.; Lee, W.; Cihlar, T. In vitro HIV-1 resistance selection to GS-8374, novelphosphonate protease inhibitor: comparison with lopinavir, atazanavir and darunavir. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gulnik, S.V.; Eissenstat, M. Approaches to the design of HIV protease inhibitors with improved resistance profiles. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2008, 3, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Sridhar, P.R.; Leshchenko, S.; Hussain, A.K.; Li, J.; Kovalevsky, A.Y.; Walters, D.E.; Wedekind, J.E.; Grum-Tokars, V.; Das, D.; Koh, Y.; Maeda, K.; Gatanaga, H.; Weber, I.T.; Mitsuya, H. Structure-based design of novel HIV-1 protease inhibitors to combat drug resistance. J. Med .Chem. 2006, 49, 5252–5261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Leshchenko-Yashchuk, S.; Anderson, D.D.; Baldridge, A.; Noetzel, M.; Miller, H. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 3902–3914. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, P.Y.; Jadhav, P.K.; Eyermann, C.J.; Hodge, C.N.; Ru, Y.; Bacheler, L.T.; Meek, J.L.; Otto, M.J.; Rayner, M.M.; Wong, Y.N.; et al. Rational design of potent, bioavailable, nonpeptide cyclic ureas as HIV protease inhibitors. Science 1994, 263, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Erickson-Viitanen, S.; Klabe, R.M.; Cawood, P.G.; O'Neal, P.L.; Meek, J.L. Potency and selectivity of inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus protease by a small nonpeptide cyclic urea, DMP 323. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1994, 38, 1628–1634. [Google Scholar] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lam, P.Y.; Ru, Y.; Jadhav, P.K.; Aldrich, P.E.; DeLucca, G.V.; Eyermann, C.J.; Chang, C.H.; Emmett, G.; Holler, E.R.; Daneker, W.F.; Li, L.; Confalone, P.N.; McHugh, R.J.; Han, Q.; Li, R.; Markwalder, J.A.; Seitz, S.P.; Sharpe, T.R.; Bacheler, L.T.; Rayner, M.M.; Klabe, R.M.; Shum,L.; Winslow, D.L.; Kornhauser, D.M.; Hodge, C.N.; et al. Cyclic HIV protease inhibitors: synthesis, conformational analysis, P2/P2' structure-activity relationship, and molecular recognition of cyclic ureas. J. Med. Chem. 1996, 39, 3514–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulten, J.; Bonham, N.M.; Nillroth, U.; Hansson, T.; Zuccarello, G.; Bouzide, A.; Aqvist, J.; Classon, B.; Danielson, U.H.; Karlen, A.; Kvarnstrom, I.; Samuelsson, B.; Hallberg, A. Cyclic HIV-1 protease inhibitors derived from mannitol: synthesis, inhibitory potencies, and computational predictions of binding affinities. J. Med. Chem. 1997, 40, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backbro, K.; Lowgren, S.; Osterlund, K.; Atepo, J.; Unge, T.; Hulten, J.; Bonham, N.M.; Schaal, W.; Karlen, A.; Hallberg, A. Unexpected binding mode of a cyclic sulfamide HIV-1 protease inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 1997, 40, 898–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judd, D.A.; Nettles, J.H.; Nevins, N.; Snyder, J.P.; Liotta, D.C.; Tang, J.; Ermolieff, J.; Schinazi, R.F.; Hill, C.L. Polyoxometalate HIV-1 protease inhibitors. A new mode of protease inhibition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 886–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosi, S.; Da Ros, T.; Spalluto, G.; Prato, M. Fullerene derivatives: an attractive tool for biological applications. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2003, 38, 913–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, S.H.; DeCamp, D.L.; Sijbesma, R.P.; Srdanov, G.; Wudl, F.; Kenyon, G.L. Inhibition of the HIV-1 protease by fullerene derivatives: model building studies and experimental verification. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 6506–6509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijbesma, R.; Srdanov, G.; Wudl, F.; Castoro, J.A.; Wilkins, C.; Friedman, S.H.; DeCamp, D.L.; Kenyon, G.L. Synthesis of a fullerene derivative for the inhibition of HIV enzymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 6510–6512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigler, P.; Kozisek, M.; Rezacova, P.; Brynda, J.; Otwinowski, Z.; Pokorna, J.; Plesek, J.; Gruner, B.; Doleckova-Maresova, L.; Masa, M.; Sedlacek, J.; Bodem, J.; Krausslich, H.G.; Kral, V.; Konvalinka, J. From nonpeptide toward noncarbon protease inhibitors: metallacarboranes as specific and potent inhibitors of HIV protease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2005, 102, 15394–15399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesnikowski, Z.J. Boron Units as Pharmacophores ----- New Applications and Opportunities of Boron Cluster Chemistry. Coll. Czech CC. 2007, 72, 1646–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A.F.; Valliant, J.F. The bioinorganic and medicinal chemistry of carboranes: from new drug discovery to molecular imaging and therapy. Dalton Trans. 2007, 4240–4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozisek, M.; Cigler, P.; Lepsik, M.; Fanfrlik, J.; Rezacova, P.; Brynda, J.; Pokorna, J.; Plesek, J.; Gruner, B.; Grantz Saskova, K.; Vaclavikova, J.; Kral, V.; Konvalinka, J. Inorganic polyhedral metallacarborane inhibitors of HIV protease: a new approach to overcoming antiviral resistance. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 4839–4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Řezáčová, P.; Pokorná, J.; Brynda, J.; Kožíšek, M.; Cígler, P.; Lepšík, M.; Fanfrlík, J.; Řezáč, J.; Šašková, K. G.; Sieglová, I.; Plešek, J.; Šícha, V.; Grüner, B.; Oberwinkler, H.; Sedláček, J.; Kräusslich, H.G.; Hobza, P.; Král, V.; Konvalinka, J. Design of HIV protease inhibitors based on inorganic polyhedral metallacarboranes. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 7132–7141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kairys, V.; Gilson, M.K.; Lather, V.; Schiffer, C.A.; Fernandes, M.X. Toward the design of mutation-resistant enzyme inhibitors: further evaluation of the substrate envelope hypothesis. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2009, 74, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabu-Jeyabalan, M.; Nalivaika, E.; Schiffer, C.A. Substrate shape determines specificity of recognition for HIV-1 protease: analysis of crystal structures of six substrate complexes. Structure 2002, 10, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altman, M.D.; Ali, A.; Reddy, G.S.; Nalam, M.N.; Anjum, S.G.; Cao, H.; Chellappan, S.; Kairys, V.; Fernandes, M.X.; Gilson, M.K.; Schiffer, C.A.; Rana, T.M.; Tidor, B. HIV-1 protease inhibitors from inverse design in the substrate envelope exhibit subnanomolar binding to drug-resistant variants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 6099–6113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontenot, G.; Johnston, K.; Cohen, J.C.; Gallaher, W.R.; Robinson, J.; Luftig, R.B. PCR amplification of HIV-1 proteinase sequences directly from lab isolates allows determination of five conserved domains. Virology 1992, 190, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingr, M.; Uhlikova, T.; Strisovsky, K.; Majerova, E.; Konvalinka, J. Kinetics of the dimerization of retroviral proteases: the "fireman's grip" and dimerization. Protein Sci. 2003, 12, 2173–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.S.; Yin, F.H.; Foundling, S.; Blomstrom, D.; Kettner, C.A. Stability and activity of human immunodeficiency virus protease: comparison of the natural dimer with a homologous, single-chain tethered dimer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 1990, 87, 9660–9664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Poorman, R.A.; Maggiora, L.L.; Heinrikson, R.L.; Kezdy, F.J. Dissociative inhibition of dimeric enzymes. Kinetic characterization of the inhibition of HIV-1 protease by its COOH-terminal tetrapeptide. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 15591–15594. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jordan, S.P.; Zugay, J.; Darke, P.L.; Kuo, L.C. Activity and dimerization of human immunodeficiency virus protease as a function of solvent composition and enzyme concentration. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 20028–20032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kuzmic, P. Kinetic assay for HIV proteinase subunit dissociation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993, 191, 998–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darke, P.L.; Jordan, S.P.; Hall, D.L.; Zugay, J.A.; Shafer, J.A.; Kuo, L.C. Dissociation and association of the HIV-1 protease dimer subunits: equilibria and rates. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pargellis, C.A.; Morelock, M.M.; Graham, E.T.; Kinkade, P.; Pav, S.; Lubbe, K.; Lamarre, D.; Anderson, P.C. Determination of kinetic rate constants for the binding of inhibitors to HIV-1 protease and for the association and dissociation of active homodimer. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 12527–12534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhlikova, T.; Konvalinka, J.; Pichova, I.; Soucek, M.; Krausslich, H.G.; Vondrasek, J. A modular approach to HIV-1 proteinase inhibitor design. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996, 222, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, I.T. Comparison of the crystal structures and intersubunit interactions of human immunodeficiency and Rous sarcoma virus proteases. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 10492–10496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wlodawer, A.; Miller, M.; Jaskolski, M.; Sathyanarayana, B.K.; Baldwin, E.; Weber, I.T.; Selk, L.M.; Clawson, L.; Schneider, J.; Kent, S.B. Conserved folding in retroviral proteases: crystal structure of a synthetic HIV-1 protease. Science 1989, 245, 616–621. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Todd, M.J.; Semo, N.; Freire, E. The structural stability of the HIV-1 protease. J. Mol. Biol. 1998, 283, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babe, L.M.; Rose, J.; Craik, C.S. Synthetic "interface" peptides alter dimeric assembly of the HIV 1 and 2 proteases. Protein Sci. 1992, 1, 1244–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schramm, H.J.; Boetzel, J.; Buttner, J.; Fritsche, E.; Gohring, W.; Jaeger, E.; Konig, S.; Thumfart, O.; Wenger, T.; Nagel, N.E.; Schramm, W. The inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus proteases by 'interface peptides'. Antiviral Res . 1996, 30, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zutshi, R.; Franciskovich, J.; Shultz, M.; Schweitzer, B.; Bishop, P.; Wilson, M.; Chmielewski, J. Targetting the Dimerization Interface of HIV-1 Protease: Inhibition with Cross-Linked Interfacial Peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 4841–4845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shultz, M.D.; Chmielewski, J. Probing the role of interfacial residues in a dimerization inhibitor of HIV-1 protease. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999, 9, 2431–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouras, A.; Boggetto, N.; Benatalah, Z.; de Rosny, E.; Sicsic, S.; Reboud-Ravaux, M. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of conformationally constrained tongs, new inhibitors of HIV-1 protease dimerization. J. Med. Chem. 1999, 42, 957–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannwarth, L.; Kessler, A.; Pethe, S.; Collinet, B.; Merabet, N.; Boggetto, N.; Sicsic, S.; Reboud-Ravaux, M.; Ongeri, S. Molecular tongs containing amino acid mimetic fragments: new inhibitors of wild-type and mutated HIV-1 protease dimerization. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 4657–4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, M.J.; Chmielewski, J. Sidechain-linked inhibitors of HIV-1 protease dimerization. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 967–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schramm, H.J.; de Rosny, E.; Reboud-Ravaux, M.; Buttner, J.; Dick, A.; Schramm, W. Lipopeptides as dimerization inhibitors of HIV-1 protease. Biol. Chem. 1999, 380, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumond, J.; Boggetto, N.; Schramm, H.J.; Schramm, W.; Takahashi, M.; Reboud-Ravaux, M. Thyroxine-derivatives of lipopeptides: bifunctional dimerization inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus-1 protease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003, 65, 1097–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannwarth, L.; Rose, T.; Dufau, L.; Vanderesse, R.; Dumond, J.; Jamart-Gregoire, B.; Pannecouque, C.; de Clercq, E.; Reboud-Ravaux, M. Dimer disruption and monomer sequestration by alkyl tripeptides are successful strategies for inhibiting wild-type and multidrug-resistant mutated HIV-1 proteases. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zutshi, R.; Chmielewski, J. Targeting the dimerization interface for irreversible inhibition of HIV-1 protease. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2000, 10, 1901–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, D.A.; Brown, C.A.; Singer, K.E.; Wang, V.; Kaufman, J.; Stahl, S.J.; Wingfield, P.; Maeda, K.; Harada, S.; Yoshimura, K.; Kosalaraksa, P.; Mitsuya, H.; Yarchoan, R. Inhibition of HIV-1 replication by a peptide dimerization inhibitor of HIV-1 protease. Antiviral Res. 2006, 72, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, D.A.; Tebbs, I.R.; Daniels, S.I.; Stahl, S.J.; Kaufman, J.D.; Wingfield, P.; Bowman, M.J.; Chmielewski, J.; Yarchoan, R. Analysis and characterization of dimerization inhibition of a multi-drug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease using a novel size-exclusion chromatographic approach. Biochem. J. 2009, 419, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lescar, J.; Brynda, J.; Rezacova, P.; Stouracova, R.; Riottot, M.M.; Chitarra, V.; Fabry, M.; Horejsi, M.; Sedlacek, J.; Bentley, G.A. Inhibition of the HIV-1 and HIV-2 proteases by a monoclonal antibody. Protein Sci. 1999, 8, 2686–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartonova, V.; Kral, V.; Sieglova, I.; Brynda, J.; Fabry, M.; Horejsi, M.; Kozisek, M.; Saskova, K.G.; Konvalinka, J.; Sedlacek, J.; Rezacova, P. Potent inhibition of drug-resistant HIV protease variants by monoclonal antibodies. Antiviral Res. 2008, 78, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rezacova, P.; Lescar, J.; Brynda, J.; Fabry, M.; Horejsi, M.; Sedlacek, J.; Bentley, G.A. Structural basis of HIV-1 and HIV-2 protease inhibition by a monoclonal antibody. Structure 2001, 9, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezacova, P.; Brynda, J.; Lescar, J.; Fabry, M.; Horejsi, M.; Sieglova, I.; Sedlacek, J.; Bentley, G.A. Crystal structure of a cross-reaction complex between an anti-HIV-1 protease antibody and an HIV-2 protease peptide. J. Struct. Biol. 2005, 149, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frutos, S.; Rodriguez-Mias, R.A.; Madurga, S.; Collinet, B.; Reboud-Ravaux, M.; Ludevid, D.; Giralt, E. Disruption of the HIV-1 protease dimer with interface peptides: structural studies using NMR spectroscopy combined with [2-(13)C]-Trp selective labeling. Biopolymers 2007, 88, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busschots, K.; De Rijck, J.; Christ, F.; Debyser, Z. In search of small molecules blocking interactions between HIV proteins and intracellular cofactors. Mol. Biosyst. 2009, 5, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganser-Pornillos, B.K.; Yeager, M.; Sundquist, W.I. The structural biology of HIV assembly. Curr. Opin. Struct. Bio. 2008, 18, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimba, N.; Nomura, A.M.; Marnett, A.B.; Craik, C.S. Herpesvirus protease inhibition by dimer disruption. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 6657–6665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camarasa, M.J.; Velazquez, S.; San-Felix, A.; Perez-Perez, M.J.; Gago, F. Dimerization inhibitors of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase, protease and integrase: a single mode of inhibition for the three HIV enzymes? Antiviral Res. 2006, 71, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornak, V.; Simmerling, C. Targeting structural flexibility in HIV-1 protease inhibitor binding. Drug Discov. Today 2007, 12, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishima, R.; Freedberg, D.I.; Wang, Y.X.; Louis, J.M.; Torchia, D.A. Flap opening and dimer-interface flexibility in the free and inhibitor-bound HIV protease, and their implications for function. Structure 1999, 7, 1047–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinelli, S.; Liu, Q.Z.; Alzari, P.M.; Hirel, P.H.; Poljak, R.J. The three-dimensional structure of the aspartyl protease from the HIV-1 isolate BRU. Biochimie 1991, 73, 1391–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottcher, J.; Blum, A.; Dorr, S.; Heine, A.; Diederich, W.E.; Klebe, G. Targeting the open-flap conformation of HIV-1 protease with pyrrolidine-based inhibitors. Chem. Med. Chem. 2008, 3, 1337–1344. [Google Scholar]

- Lescar, J.; Stouracova, R.; Riottot, M.M.; Chitarra, V.; Brynda, J.; Fabry, M.; Horejsi, M.; Sedlacek, J.; Bentley, G.A. Preliminary crystallographic studies of an anti-HIV-1 protease antibody that inhibits enzyme activity. Protein Sci. 1996, 5, 966–968. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lescar, J.; Stouracova, R.; Riottot, M.M.; Chitarra, V.; Brynda, J.; Fabry, M.; Horejsi, M.; Sedlacek, J.; Bentley, G.A. Three-dimensional structure of an Fab-peptide complex: structural basis of HIV-1 protease inhibition by a monoclonal antibody. J. Mol. Biol. 1997, 267, 1207–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Montero, J.V.; Barreiro, P.; Soriano, V. HIV protease inhibitors: recent clinical trials and recommendations on use. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2009, 10, 1615–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, J.H.; Pujari, S. Protease inhibitor therapy in resource-limited settings. Curr. Opin. HIV 2008, 3, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2009 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.