Abstract

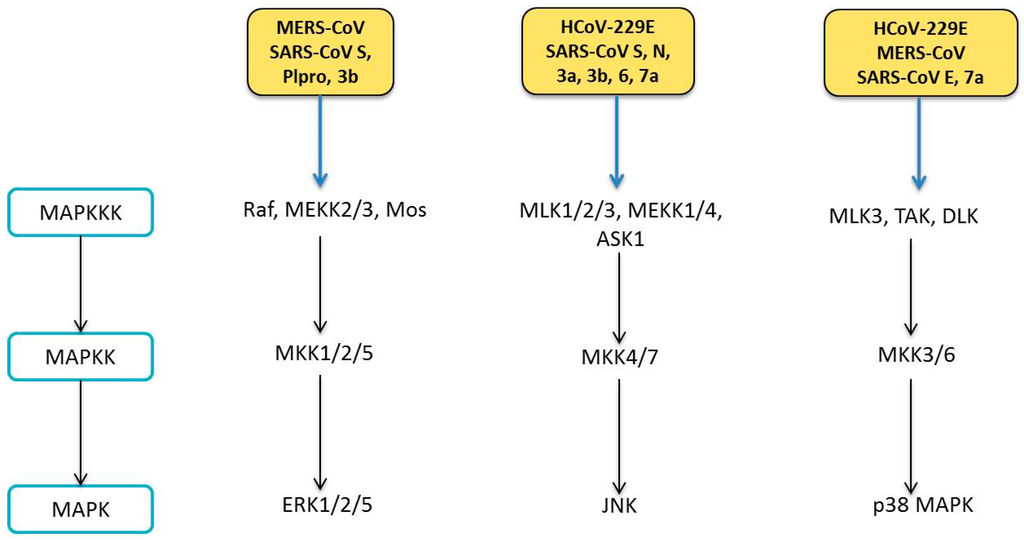

Human coronaviruses (HCoVs) are known respiratory pathogens associated with a range of respiratory outcomes. In the past 14 years, the onset of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) have thrust HCoVs into spotlight of the research community due to their high pathogenicity in humans. The study of HCoV-host interactions has contributed extensively to our understanding of HCoV pathogenesis. In this review, we discuss some of the recent findings of host cell factors that might be exploited by HCoVs to facilitate their own replication cycle. We also discuss various cellular processes, such as apoptosis, innate immunity, ER stress response, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway that may be modulated by HCoVs.

Keywords:

human coronavirus; virus–host interactions; apoptosis; innate immunity; ER stress; MAPK; NF-κB 1. Introduction

Human coronaviruses (HCoVs) represent a major group of coronaviruses (CoVs) associated with multiple respiratory diseases of varying severity, including common cold, pneumonia and bronchilitis [1]. Today, HCoVs are recognised as one of the most rapidly evolving viruses owing to its high genomic nucleotide substitution rates and recombination [2]. In recent years, evolution of HCoVs has also been expedited by factors such as urbanization and poultry farming. These have permitted the frequent mixing of species and facilitated the crossing of species barrier and genomic recombination of these viruses [3]. To date, six known HCoVs have been identified, namely HCoV-229E, HCoV-NL63, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-HKU1, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV); of which, four HCoVs (HCoV-229E, HCoV-NL63, HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-HKU1) are globally circulated in the human population and contribute to approximately one-third of common cold infections in humans [4]. In severe cases, these four HCoVs can cause life-threatening pneumonia and bronchiolitis especially in elderly, children and immunocompromised patients [1,5,6]. Besides respiratory illnesses, they may also cause enteric and neurological diseases [7,8,9,10,11].

SARS-CoV first emerged in 2002–2003 in Guangdong, China as an atypical pneumonia marked by fever, headache and subsequent onset of respiratory symptoms such as cough and pneumonia, which may later develop into life-threatening respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome [12]. Being highly transmissible among humans, it quickly spread across 29 countries, infecting more than 8000 individuals with a mortality rate of about 10% [13,14]. Originally, palm civets were thought to be the natural reservoir for the virus [15]. However, subsequent phylogenetic studies pointed to the bat origin of SARS-CoV based on sequences of SARS-like virus found in bats [16]. The MERS-CoV epidemic surfaced in Saudi Arabia in 2012 with similar clinical symptoms as SARS-CoV but with a much higher mortality rate of about 35% [17]. Unlike SARS-CoV, which exhibits super-spreader events, transmission of MERS-CoV is geographically limited [12]. In fact, reported cases of MERS-CoV often stem from outbreaks within the Middle Eastern countries or recent travel to the region [18,19].

Taxonomy, Genomic Structure and Morphology

CoVs are a group of large enveloped RNA viruses under the Coronaviridae family. Together with Artierivirdae and Roniviridae, Coronaviridae is classified under the Nidovirale order [20]. As proposed by the International Committee for Taxonomy of Viruses, CoVs are further categorized into four main genera, Alpha-, Beta-, Gamma- and Deltacoronaviruses based on sequence comparisons of entire viral genomes [21,22]. These CoVs can infect a wide variety of hosts, including avian, swine and humans. HCoVs are identified to be either in the Alpha- or Betacoronavirus genera, including Alphacoronaviruses, HCoV-229E and HCoV-NL63, and Betacoronaviruses, HCoV-HKU1, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and HCoV-OC43 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Classification of human coronavirus.

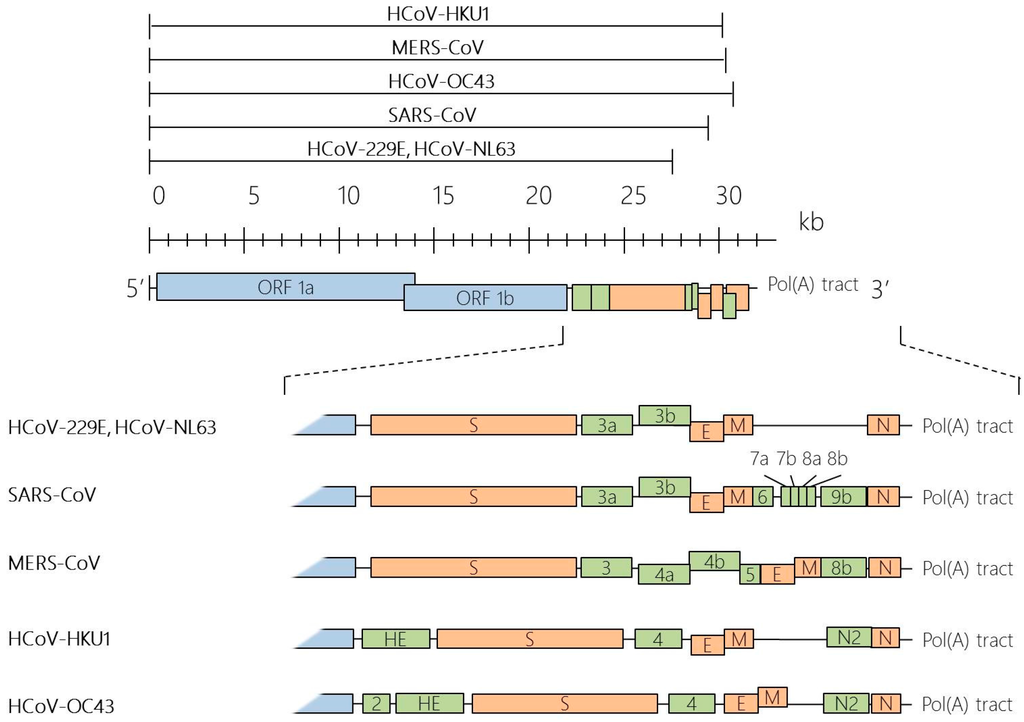

Under the electron microscope, the CoV virions appear to be roughly spherical or moderately pleomorphic, with distinct “club-like” projections formed by the spike (S) protein [23,24]. Within the virion interior lies a helically symmetrical nucleocapsid that encloses a single-stranded and positive sense RNA viral genome of an extraordinarily large size of about 26 to 32 kilobases [20]. The positive sense viral genomic RNA acts as a messenger RNA (mRNA), comprising a 5′ terminal cap structure and a 3′ poly A tail. This genomic RNA acts in three capacities during the viral life cycle: (1) as an initial RNA of the infectious cycle; (2) as a template for replication and transcription; and (3) as a substrate for packaging into the progeny virus. The replicase-transcriptase is the only protein translated from the genome, while the viral products of all downstream open reading frames are derived from subgenomic mRNAs. In all CoVs, the replicase gene makes up approximately 5′ two-thirds of the genome and is comprised of two overlapping open reading frames (ORFs), ORF1a and ORF1b, which encodes 16 non-structural proteins. The final one-third of the CoV genomic RNA encodes CoV canonical set of four structural protein genes, in the order of spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M) and nucleocapsid (N). In addition, several accessory ORFs are also interspersed along the structural protein genes and the number and location varies among CoV species [25] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Genome organisation of human coronaviruses (HCoVs). HCoV genomes range from about 26 to 32 kilobases (kb) in size, as indicated by the black lines above the scale. Coronavirus (CoV) genome is typically arranged in the order of 5′-ORF1a-ORF1b-S-E-M-N-3′. The overlapping open reading frames (ORF) ORF1a and ORF1b comprise two-thirds of the coronavirus genome, which encodes for all the viral components required for viral RNA synthesis. The other one-third of the genome at the 3′ end encodes for a set of structural (orange) and non-structural proteins (green).

2. Involvement of Host Factors in Viral Replication and Pathogenesis

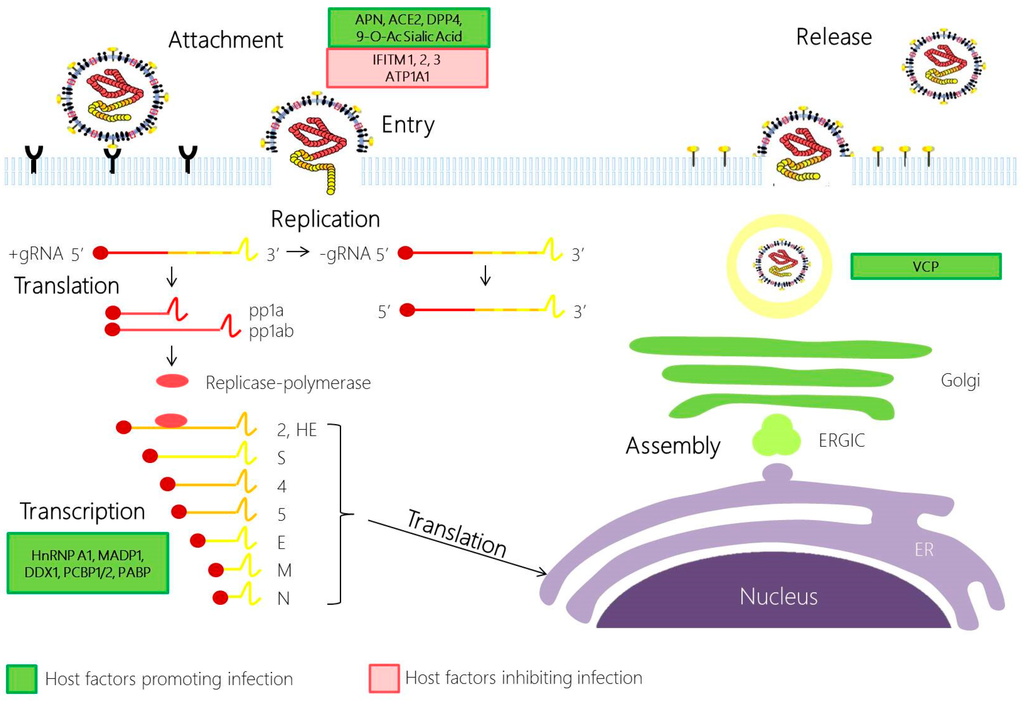

As intracellular obligate parasites, HCoVs exploit the host cell machinery for their own replication and spread. Since virus–host interactions form the basis of diseases, knowledge about their interplay is of great research interest. Here, we describe what is currently known of the cell’s contribution in CoV infection cycle: attachment; entry into the host cell; translation of the replicase-transcriptase; replication of genome and transcription of mRNAs; and assembly and budding of newly packaged virions (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Coronavirus replication cycle. Coronavirus infection begins with the attachment of the S1 domain of the spike protein (S) with its cognate receptor. This drives the conformational change in the S2 subunit in S, promoting the fusion of the viral and cell plasma membrane. Following the release of the nucleocapsid to the cytoplasm, the viral gRNA is translated through ribosomal frameshifting to produce polyproteins pp1a and pp1ab. pp1a and pp1ab are autoproteolytically processed by host and viral proteases to generate 16 non-structural proteins (NSPs), which will then be assembled to form the replicase-polymerase. The replicase-polymerase is involved in the coronaviral replication, a process in which the genomic RNA are replicated and the subgenomic RNA will be transcribed and translated to form the structural proteins. The viral products produced will be assembled in the ERGIC, and bud out as a smooth-wall vesicle to the plasma membrane to egress via exocytosis. Host factors that promote infection and inhibit infection are highlighted in green and red, respectively. APN, aminopeptidase N; ACE2, Angiotensin converting enzyme 2; DPP4, dipeptidyl peptidase 4; 9-O-Ac Sialic Acid, 9-O-Acetylated Sialic Acid; IFITM, Interferon induced transmembrane protein; ATP1A1, ATPase, Na+/K+ Transporting, Alpha 1 Polypeptide; HnRNP A1, Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1; MADP1, Zinc Finger CCHC-Type and RNA Binding Motif 1; DDX1, ATP-dependent RNA Helicase; PCBP1/2, Poly r(C) binding protein 1/2; PABP, Poly A binding protein; COPB2, Coatomer protein complex, subunit beta 2 (beta prime); GAPDH, Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; ERGIC, Endoplasmic reticulum Golgi intermediate compartment; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; VCP, Valosin-Containing Protein.

2.1. Coronavirus Attachment and Entry

CoV infection is initiated by the attachment to specific host cellular receptors via the spike (S) protein. The host receptor is a major determinant of pathogenicity, tissue tropism and host range of the virus. The S protein comprises of two domains: S1 and S2. The interaction between the S1 domain and its cognate receptor triggers a conformational change in the S protein, which then promotes membrane fusion between the viral and cell membrane through the S2 domain. Today, the main host cell receptors utilised by all HCoVs are known: aminopeptidase N by HCoV-229E [26], angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) by SARS-CoV [27] and HCoV-NL63 [28,29], dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) by MERS-CoV [30] and 9-O-acetylated sialic acid by HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-HKU1 [31,32].

Apart from the conventional endosomal route of entry, some CoVs may also gain entry into the cell via the non-endosomal pathway, or a combination of both. The low pH in the cellular environment and endosomal cysteine protease cathepsins may help to facilitate membrane fusion and endosomal CoV cell entry [33]. Recent evidence has supported the role of cathepsin L in SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV entry [34,35,36]. Other host proteases, such as transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) and airway trypsin-like protease TMPRSS11D, could also perform S1/S2 cleavage to activate the S protein for non-endosomal virus entry at the cell plasma membrane during HCoV-229E and SARS-CoV infection [37,38]. In addition, MERS-CoV is also activated by furin, a serine endopeptidase that has been implicated in the cell entry of other RNA viruses and S1/S2 cleavage during viral egress [39].

Many host cells also utilise its own factors to restrict viral entry. Using cell culture system and pseudotype virus, many groups have identified a family of interferon inducible transmembrane proteins (IFITM), which could inhibit global circulating HCoV-229E and HCoV-NL63 S protein mediated entry, and also the highly pathogenic SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV [12,40]. While the IFITM mode of action remains elusive, cell-to-cell fusion assays performed by some research groups suggest that IFITM3 blocks the enveloped virus entry by preventing fusion of the viral envelope with the plasma membrane or endosomal membranes through modulating the host membrane fluidity [41].

2.2. Coronavirus Replication

Following the release and uncoating of viral nucleocapsid to the cytoplasm, CoV replication begins with the translation of ORF 1a and 1b into polyproteins pp1a (4382 amino acids) and pp1ab (7073 amino acids). Here, the downstream ORF1b is translated through ribosomal frameshifting mechanism, in which a translating ribosome shifts one nucleotide in the −1 direction, from the ORF1a reading frame into ORF1b reading frame. This repositioning is enabled by two RNA elements—a 5′-UUUAAAC-3′ heptanucleotide slippery sequence and RNA pseudoknot structure. Subsequently, polyproteins pp1a and pp1ab are cleaved into at least 15 nsp, which assemble and form the replication-transcription complex. With the assembly of the replicase-polymerase, the full-length positive strand of genomic RNA is transcribed to form a full-length negative-strand template for the synthesis of new genomic RNAs and overlapping subgenomic negative-strand templates. These subgenomic mRNAs are then transcribed and translated to produce the structural and accessory proteins. Several heterologous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNA) family members (hnRNPA1, PTB, SYN-CRYP) have been found to be essential for efficient RNA replication [42]. Other RNA-binding proteins have also been suggested to play a role in CoV replication, such as m-aconitase and poly-A-binding protein (PABP), DDX1, PCBP1/2 and zinc finger CCHC-type and RNA-binding motif 1 (MADP1) [43,44,45].

2.3. Coronavirus Assembly and Egress

The assembly of virions is quickly ensued with the accumulation of new genomic RNA and structural components. In this phase of the infection cycle, the helical nucleocapsid containing the genomic RNA interacts with other viral structural proteins (S, E and M proteins) to form the assembled virion. The assembly of CoV particles is completed through budding of the helical nucleocapsid through membranes early in the secretory pathway from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC). The contributions of the host in this phase of the infection cycle have rarely been explored. Currently, it is known that the M protein orchestrates the entire assembly process by selecting and organizing the viral envelope components at the assembly sites and by mediating the interactions with the nucleocapsid to allow the budding of virions [46]. The M protein interacts with different viral structural proteins, such as the E protein, to assemble into a mature virus. This interaction generates the scaffold of the virion envelope and induces the budding and release of the M protein-modified membrane and with the S protein to assemble the spikes into the viral envelope [46,47]. Following assembly and budding, the virions are transported in vesicles and eventually released by exocytosis. In a recent study, an inhibition of a Valosin-containing protein (VCP/p97) resulted in virus accumulation in early endosome in infectious bronchitis virus (IBV), suggesting a role for VCP in the maturation of virus-loaded endosomes [48].

8. Conclusions

The relationship between a virus and its host is a complicated affair: a myriad of factors from the virus and the host are involved in viral infection and consequential pathogenesis. During viral infections, the host must respond to the virus by putting multiple lines of defence mechanisms in place. As intracellular obligate parasites, viruses have also evolved various strategies to hijack the host machineries. In this review, we first showed how viral factors could manipulate the host cell to expedite its own replication cycle and pathogenesis. We also highlighted how multiple cellular and viral factors come into play in their long-standing battle against one another.

For years, HCoVs have been identified as mild respiratory pathogens that affect the human population. However, it was the emergence of SARS-CoV that thrust these human viruses into the spotlight of the research field. Therefore, most of the HCoV research today is pertained towards SARS-CoV. While the recent MERS-CoV outbreak has been mostly limited to the Middle East region, it is likely that more emerging or re-emerging HCoVs might surface to threaten the global public health, as seen from the high mortality rates in the past two outbreaks: SARS-CoV (10%) and MERS-CoV (35%). Therefore, study of the pathogenesis of all HCoVs would gain more insights for the development of antiviral therapeutics and vaccines.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by a Competitive Research Programme (CRP) grant (NRF-CRP8-2011-05), the National Research Foundation, Singapore, an Academic Research Fund (AcRF) Tier 1 grant (RGT17/13), Nanyang Technological University and Ministry of Education, Singapore, and an AcRF Tier 2 grant (ACR47/14), Ministry of Education, Singapore.

Author Contributions

Yvonne Xinyi Lim and Yan Ling Ng wrote the paper; and James P. Tam and Ding Xiang Liu revised the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pene, F.; Merlat, A.; Vabret, A.; Rozenberg, F.; Buzyn, A.; Dreyfus, F.; Cariou, A.; Freymuth, F.; Lebon, P. Coronavirus 229E-Related Pneumonia in Immunocompromised Patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 37, 929–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijgen, L.; Keyaerts, E.; Moës, E.; Maes, P.; Duson, G.; van Ranst, M. Development of One-Step, Real-Time, Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase PCR Assays for Absolute Quantitation of Human Coronaviruses OC43 and 229E. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 5452–5456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B.A.; Grace, D.; Kock, R.; Alonso, S.; Rushton, J.; Said, M.Y.; McKeever, D.; Mutua, F.; Young, J.; McDermott, J.; et al. Zoonosis emergence linked to agricultural intensification and environmental change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 21, 8399–8340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Hoek, L. Human coronaviruses: What do they cause? Antivir. Ther. 2007, 12, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Walsh 2007, E.E.; Shin, J.H.; Falsey, A.R. Clinical Impact of Human Coronaviruses 229E and OC43 Infection in Diverse Adult Populations. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 208, 1634–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorse, G.J.; O’Connor, T.Z.; Hall, S.L.; Vitale, J.N.; Nichol, K.L. Human Coronavirus and Acute Respiratory Illness in Older Adults with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 199, 847–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbour, N.; Day, R.; Newcombe, J.; Talbot, P.J. Neuroinvasion by Human Respiratory Coronaviruses. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 8913–8921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbour, N.; Ekandé, S.; Côté, G.; Lachance, C.; Chagnon, F.; Tardieu, M.; Cashman, N.R.; Talbot, P.J. Persistent Infection of Human Oligodendrocytic and Neuroglial Cell Lines by Human Coronavirus 229E. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 3326–3337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jacomy, H.; Fragoso, G.; Almazan, G.; Mushynski, W.E.; Talbot, P.J. Human coronavirus OC43 infection induces chronic encephalitis leading to disabilities in BALB/C mice. Virology 2006, 349, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vabret, A.; Mourez, T.; Gouarin, S.; Petitjean, J.; Freymuth, F. An Outbreak of Coronavirus OC43 Respiratory Infection in Normandy, France. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 36, 985–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smuts, H. Human coronavirus NL63 infections in infants hospitalised with acute respiratory tract infections in South Africa. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2008, 2, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, R.L.; Donaldson, E.F.; Baric, R.S. A decade after SARS: Strategies for controlling emerging coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frieman, M.; Baric, R. Mechanisms of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Pathogenesis and Innate Immunomodulation. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. MMBR 2008, 72, 672–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peiris, J.S.M.; Guan, Y.; Yuen, K.Y. Severe acute respiratory syndrome. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, S88–S97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Yan, M.; Xu, H.; Liang, W.; Kan, B.; Zheng, B.; Chen, H.; Zheng, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, E.; et al. SARS-CoV Infection in a Restaurant from Palm Civet. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005, 11, 1860–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, B.; Ge, X.; Wang, L.-F.; Shi, Z. Bat origin of human coronaviruses. Virol. J. 2015, 12, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Cheon, S.; Min, C.-K.; Sohn, K.M.; Kang, Y.J.; Cha, Y.-J.; Kang, J.I.; Han, S.K.; Ha, N.Y.; Kim, G.; et al. Spread of Mutant Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus with Reduced Affinity to Human CD26 during the South Korean Outbreak. mBio 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oboho, I.K.; Tomczyk, S.M.; Al-Asmari, A.M.; Banjar, A.A.; Al-Mugti, H.; Aloraini, M.S.; Alkhaldi, K.Z.; Almohammadi, E.L.; Alraddadi, B.M.; Gerber, S.I.; et al. 2014 MERS-CoV Outbreak in Jeddah—A Link to Health Care Facilities. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Korean Society of Infectious Diseases; Korean Society for Healthcare-associated Infection Control and Prevention. An Unexpected Outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Infection in the Republic of Korea, 2015. Infect. Chemother. 2015, 47, 120–122. [Google Scholar]

- Masters, P.S. The Molecular Biology of Coronaviruses Advances in Virus Research; Academic Press: Massachusetts, MA, USA, 2006; Volume 66, pp. 193–292. [Google Scholar]

- McBride, R.; Fielding, B.C. The Role of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)-Coronavirus Accessory Proteins in Virus Pathogenesis. Viruses 2012, 4, 2902–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorbalenya, A.E.; Snijder, E.J.; Spaan, W.J.M. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Phylogeny: Toward Consensus. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 7863–7866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolesnikova, L.; Slenczka, W.; Brodt, H.; Klenk, H.; Becker, S. Electron microscopy in diagnostics of SARS case. Microsc. Microanal. 2003, 9, 438–439. [Google Scholar]

- Marsolais, G.; Berthiaume, L.; DiFranco, E.; Marois, P. Rapid Diagnosis by Electron Microscopy of Avian Coronavirus Infection. Can. J. Comp. Med. 1971, 35, 285–288. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.X.; Fung, T.S.; Chong, K.K.-L.; Shukla, A.; Hilgenfeld, R. Accessory proteins of SARS-CoV and other coronaviruses. Antivir. Res. 2014, 109, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeager, C.L.; Ashmun, R.A.; Williams, R.K.; Cardellichio, C.B.; Shapiro, L.H.; Look, A.T.; Holmes, K.V. Human aminopeptidase N is a receptor for human coronavirus 229E. Nature 1992, 357, 420–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Moore, M.J.; Vasilieva, N.; Sui, J.; Wong, S.K.; Berne, M.A.; Somasundaran, M.; Sullivan, J.L.; Luzuriaga, K.; Greenough, T.C.; et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature 2003, 426, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Sui, J.; Huang, I.C.; Kuhn, J.H.; Radoshitzky, S.R.; Marasco, W.A.; Choe, H.; Farzan, M. The S proteins of human coronavirus NL63 and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus bind overlapping regions of ACE2. Virology 2007, 367, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.; Li, W.; Peng, G.; Li, F. Crystal structure of NL63 respiratory coronavirus receptor-binding domain complexed with its human receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 19970–19974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Doremalen, N.; Miazgowicz, K.L.; Milne-Price, S.; Bushmaker, T.; Robertson, S.; Scott, D.; Kinne, J.; McLellan, J.S.; Zhu, J.; Munster, V.J. Host Species Restriction of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus through Its Receptor, Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 9220–9232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Dong, W.; Milewska, A.; Golda, A.; Qi, Y.; Zhu, Q.K.; Marasco, W.A.; Baric, R.S.; Sims, A.C.; Pyrc, K.; et al. Human Coronavirus HKU1 Spike Protein Uses O-Acetylated Sialic Acid as an Attachment Receptor Determinant and Employs Hemagglutinin-Esterase Protein as a Receptor-Destroying Enzyme. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 7202–7213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, N.; Pewe, L.; Trandem, K.; Perlman, S. Murine encephalitis caused by HCoV-OC43, a human coronavirus with broad species specificity, is partly immune-mediated. Virology 2006, 347, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zumla, A.; Chan, J.W.; Azhar, E.I.; Hui, D.C.; Yuen, K. Coronaviruses—Drug discovery and therapeutic options. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016, 15, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch, B.J.; Bartelink, W.; Rottier, P.J.M. Cathepsin L Functionally Cleaves the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Class I Fusion Protein Upstream of Rather than Adjacent to the Fusion Peptide. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 8887–8890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, Z.; Dominguez, S.R.; Holmes, K.V. Role of the Spike Glycoprotein of Human Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in Virus Entry and Syncytia Formation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, G.; Gosalia, D.N.; Rennekamp, A.J.; Reeves, J.D.; Diamond, S.L.; Bates, P. Inhibitors of cathepsin L prevent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 11876–11881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertram, S.; Dijkman, R.; Habjan, M.; Heurich, A.; Gierer, S.; Glowacka, I.; Welsch, K.; Winkler, M.; Schneider, H.; Hofmann-Winkler, H.; et al. TMPRSS2 Activates the Human Coronavirus 229E for Cathepsin-Independent Host Cell Entry and Is Expressed in Viral Target Cells in the Respiratory Epithelium. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 6150–6160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertram, S.; Glowacka, I.; Müller, M.A.; Lavender, H.; Gnirss, K.; Nehlmeier, I.; Niemeyer, D.; He, Y.; Simmons, G.; Drosten, C.; et al. Cleavage and Activation of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Spike Protein by Human Airway Trypsin-Like Protease. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 13363–13372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millet, J.K.; Whittaker, G.R. Host cell entry of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus after two-step, furin-mediated activation of the spike protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 15214–15219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, I.C.; Bailey, C.C.; Weyer, J.L.; Radoshitzky, S.R.; Becker, M.M.; Chiang, J.J.; Brass, A.L.; Ahmed, A.A.; Chi, X.; Dong, L.; et al. Distinct Patterns of IFITM-Mediated Restriction of Filoviruses, SARS Coronavirus, and Influenza A Virus. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1001258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Markosyan, R.M.; Zheng, Y.-M.; Golfetto, O.; Bungart, B.; Li, M.; Ding, S.; He, Y.; Liang, C.; Lee, J.C.; et al. IFITM Proteins Restrict Viral Membrane Hemifusion. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.; Chen, Q.; Chen, J.; Chen, K.; Shen, X.; Jiang, H. The nucleocapsid protein of SARS coronavirus has a high binding affinity to the human cellular heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1. FEBS Lett. 2005, 579, 2623–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanda, S.K.; Leibowitz, J.L. Mitochondrial Aconitase Binds to the 3′ Untranslated Region of the Mouse Hepatitis Virus Genome. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 3352–3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.-H.; Chen, P.-J.; Yeh, S.-H. Nucleocapsid Phosphorylation and RNA Helicase DDX1 Recruitment Enables Coronavirus Transition from Discontinuous to Continuous Transcription. Cell Host Microb. 2014, 16, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.W.; Hong, W.; Liu, D.X. Binding of the 5′-untranslated region of coronavirus RNA to zinc finger CCHC-type and RNA-binding motif 1 enhances viral replication and transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 5065–5077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuman, B.W.; Kiss, G.; Kunding, A.H.; Bhella, D.; Baksh, M.F.; Connelly, S.; Droese, B.; Klaus, J.P.; Makino, S.; Sawicki, S.G.; et al. A structural analysis of M protein in coronavirus assembly and morphology. J. Struct. Biol. 2011, 174, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.; Wu, D.; Shen, C.; Chen, K.; Shen, X.; Jiang, H. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus membrane protein interacts with nucleocapsid protein mostly through their carboxyl termini by electrostatic attraction. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2006, 38, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, H.H.; Kumar, P.; Tay, F.P.L.; Moreau, D.; Liu, D.X.; Bard, F. Genome-Wide Screen Reveals Valosin-Containing Protein Requirement for Coronavirus Exit from Endosomes. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 11116–11128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, J.F.R.; Wyllie, A.H.; Currie, A.R. Apoptosis: A Basic Biological Phenomenon with Wide-ranging Implications in Tissue Kinetics. Br. J. Cancer 1972, 26, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulares, A.H.; Yakovlev, A.G.; Ivanova, V.; Stoica, B.A.; Wang, G.; Iyer, S.; Smulson, M. Role of Poly(ADP-ribose) Polymerase (PARP) Cleavage in Apoptosis: Caspase 3-resistant parp mutant increases rates of apoptosis in transfected cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 22932–22940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segawa, K.; Kurata, S.; Yanagihashi, Y.; Brummelkamp, T.R.; Matsuda, F.; Nagata, S. Caspase-mediated cleavage of phospholipid flippase for apoptotic phosphatidylserine exposure. Science 2014, 344, 1164–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walczak, H.; Krammer, P.H. The CD95 (APO-1/Fas) and the TRAIL (APO-2L) Apoptosis Systems. Exp. Cell Res. 2000, 256, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bender, L.M.; Morgan, M.J.; Thomas, L.R.; Liu, Z.G.; Thorburn, A. The adaptor protein TRADD activates distinct mechanisms of apoptosis from the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Cell Death Differ. 2005, 12, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stennicke, H.R.; Jürgensmeier, J.M.; Shin, H.; Deveraux, Q.; Wolf, B.B.; Yang, X.; Zhou, Q.; Ellerby, H.M.; Ellerby, L.M.; Bredesen, D.; et al. Pro-caspase-3 Is a Major Physiologic Target of Caspase-8. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 27084–27090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, R.C.; Cullen, S.P.; Martin, S.J. Apoptosis: Controlled demolition at the cellular level. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebbagh, M.; Renvoize, C.; Hamelin, J.; Riche, N.; Bertoglio, J.; Breard, J. Caspase-3-mediated cleavage of ROCK I induces MLC phosphorylation and apoptotic membrane blebbing. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001, 3, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Zhu, H.; Xu, C.-J.; Yuan, J. Cleavage of BID by Caspase 8 Mediates the Mitochondrial Damage in the Fas Pathway of Apoptosis. Cell 1998, 94, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

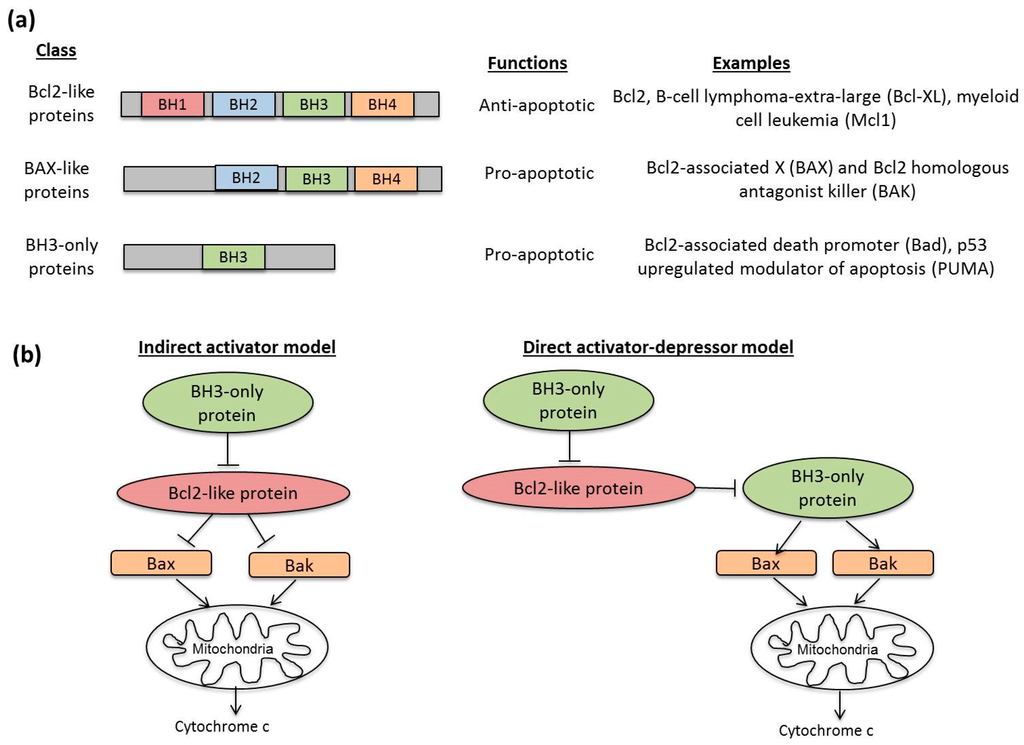

- Benedict, C.A.; Norris, P.S.; Ware, C.F. To kill or be killed: Viral evasion of apoptosis. Nat. Immunol. 2002, 3, 1013–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvansakul, M.; Hinds, M.G. Structural biology of the Bcl-2 family and its mimicry by viral proteins. Cell Death Dis. 2013, 4, e909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, A.F.; Lyles, D.S. Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Induces Apoptosis Primarily through Bak Rather than Bax by Inactivating Mcl-1 and Bcl-XL. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 9102–9112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aillet, F.; Masutani, H.; Elbim, C.; Raoul, H.; Chêne, L.; Nugeyre, M.T.; Paya, C.; Barré-Sinoussi, F.; Gougerot-Pocidalo, M.A.; Israël, N. Human immunodeficiency virus induces a dual regulation of Bcl-2, resulting in persistent infection of CD4(+) T- or monocytic cell lines. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 9698–9705. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tamura, R.; Kanda, T.; Imazeki, F.; Wu, S.; Nakamoto, S.; Tanaka, T.; Arai, M.; Fujiwara, K.; Saito, K.; Roger, T.; et al. Hepatitis C Virus Nonstructural 5A Protein Inhibits Lipopolysaccharide-Mediated Apoptosis of Hepatocytes by Decreasing Expression of Toll-Like Receptor 4. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 204, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aweya, J.J.; Sze, C.W.; Bayega, A.; Mohd-Ismail, N.K.; Deng, L.; Hotta, H.; Tan, Y.J. NS5B induces up-regulation of the BH3-only protein, BIK, essential for the hepatitis C virus RNA replication and viral release. Virology 2015, 474, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura-Lopez, Y.; Villegas-Sepúlveda, N.; Gómez, B. RSV P-protein impairs extrinsic apoptosis pathway in a macrophage-like cell line persistently infected with respiratory syncytial virus. Virus Res. 2015, 204, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mocarski, E.S.; Upton, J.W.; Kaiser, W.J. Viral infection and the evolution of caspase 8-regulated apoptotic and necrotic death pathways. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 12, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amara, A.; Mercer, J. Viral apoptotic mimicry. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

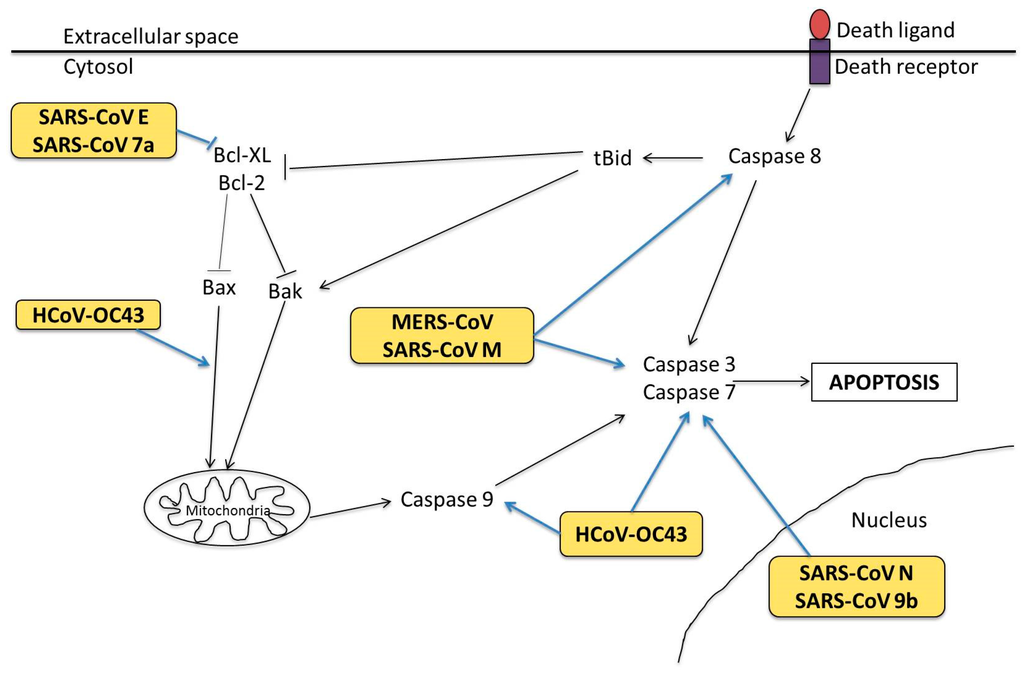

- Collins, A.R. Induction of Apoptosis in MRC-5, Diploid Human Fetal Lung Cells after Infection with Human Coronavirus OC43. In The Nidoviruses: Coronaviruses and Arteriviruses; Lavi, E., Weiss, S.R., Hingley, S.T., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 677–682. [Google Scholar]

- Pyrc, K.; Berkhout, B.; van der Hoek, L. The Novel Human Coronaviruses NL63 and HKU1. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 3051–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, J.; Korteweg, C. Pathology and Pathogenesis of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. Am. J. Pathol. 2007, 170, 1136–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, X.; Hill, T.E.; Morimoto, C.; Peters, C.J.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Tseng, C.-T.K. Bilateral Entry and Release of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Induces Profound Apoptosis of Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 9953–9958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, M.-L.; Yao, Y.; Jia, L.; Chan, J.F.W.; Chan, K.-H.; Cheung, K.-F.; Chen, H.; Poon, V.K.M.; Tsang, A.K.L.; To, K.K.W.; et al. MERS coronavirus induces apoptosis in kidney and lung by upregulating Smad7 and FGF2. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 16004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desforges, M.; Coupanec, A.; Brison, É.; Meessen-Pinard, M.; Talbot, P.J. Neuroinvasive and Neurotropic Human Respiratory Coronaviruses: Potential Neurovirulent Agents in Humans. In Proceedings of the Infectious Diseases and Nanomedicine I: First International Conference (ICIDN-2012), Kathmandu, Nepal, 15–18 December 2012; Adhikari, R., Thapa, S., Eds.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2014; pp. 75–96. [Google Scholar]

- Desforges, M.; Le Coupanec, A.; Stodola, J.K.; Meessen-Pinard, M.; Talbot, P.J. Human coronaviruses: Viral and cellular factors involved in neuroinvasiveness and neuropathogenesis. Virus Res. 2014, 194, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favreau, D.J.; Meessen-Pinard, M.; Desforges, M.; Talbot, P.J. Human Coronavirus-Induced Neuronal Programmed Cell Death Is Cyclophilin D Dependent and Potentially Caspase Dispensable. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krähling, V.; Stein, D.A.; Spiegel, M.; Weber, F.; Mühlberger, E. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Triggers Apoptosis via Protein Kinase R but Is Resistant to Its Antiviral Activity. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 2298–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, A.R. In Vitro Detection of Apoptosis in Monocytes/Macrophages Infected with Human Coronavirus. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2002, 9, 1392–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yan, Y.; Nguyen, J.; Ng, B.; Lu, H.; Brendese, J.; Yang, F.; Wang, H.; et al. Bcl-xL inhibits T-cell apoptosis induced by expression of SARS coronavirus E protein in the absence of growth factors. Biochem. J. 2005, 392, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, T.; Li, W.; Dimitrov, D.S. Discovery of T-Cell Infection and Apoptosis by Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. J. Infect. Dis. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, H.; Zhou, J.; Wong, B.H.-Y.; Li, C.; Chan, J.F.-W.; Cheng, Z.-S.; Yang, D.; Wang, D.; Lee, A.C.; Li, C.; et al. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Efficiently Infects Human Primary T Lymphocytes and Activates the Extrinsic and Intrinsic Apoptosis Pathways. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 213, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesel-Lemoine, M.; Millet, J.; Vidalain, P.-O.; Law, H.; Vabret, A.; Lorin, V.; Escriou, N.; Albert, M.L.; Nal, B.; Tangy, F. A Human Coronavirus Responsible for the Common Cold Massively Kills Dendritic Cells but Not Monocytes. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 7577–7587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiegel, M.; Schneider, K.; Weber, F.; Weidmann, M.; Hufert, F. Interaction of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus with dendritic cells. J. Gen. Virol. 2006, 87, 1953–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordi, L.; Castilletti, C.; Falasca, L.; Ciccosanti, F.; Calcaterra, S.; Rozera, G.; Di Caro, A.; Zaniratti, S.; Rinaldi, A.; Ippolito, G.; et al. Bcl-2 inhibits the caspase-dependent apoptosis induced by SARS-CoV without affecting virus replication kinetics. Arch. Virol. 2005, 151, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, L.; Yang, R.; Guo, L.; Qu, J.; Wang, J.; Hung, T. Apoptosis Induced by the SARS-Associated Coronavirus in Vero Cells Is Replication-Dependent and Involves Caspase. DNA Cell Biol. 2005, 24, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, B.S.F.; Chan, K.-h.; Cheng, V.C.C.; Woo, P.C.Y.; Lau, S.K.P.; Lam, C.C.K.; Chan, T.L.; Wu, A.K.; Hung, I.F.; Leung, S.Y.; et al. Comparative Host Gene Transcription by Microarray Analysis Early after Infection of the Huh7 Cell Line by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus and Human Coronavirus 229E. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 6180–6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, K.Y.C.; Yeung, Y.S.; Hon, C.C.; Zeng, F.; Law, K.M.; Leung, F.C.C. Adenovirus-mediated expression of the C-terminal domain of SARS-CoV spike protein is sufficient to induce apoptosis in Vero E6 cells. FEBS Lett. 2005, 579, 6699–6704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surjit, M.; Liu, B.; Jameel, S.; Chow, V.T.K.; Lal, S.K. The SARS coronavirus nucleocapsid protein induces actin reorganization and apoptosis in COS-1 cells in the absence of growth factors. Biochem. J. 2004, 383, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.-J.; Fielding, B.C.; Goh, P.-Y.; Shen, S.; Tan, T.H.P.; Lim, S.G.; Hong, W. Overexpression of 7a, a Protein Specifically Encoded by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus, Induces Apoptosis via a Caspase-Dependent Pathway. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 14043–14047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Z.; Wong, C.K.; Li, P.; Xie, Y. A SARS-CoV protein, ORF-6, induces caspase-3 mediated, ER stress and JNK-dependent apoptosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1780, 1383–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, K.; Åkerström, S.; Sharma, A.K.; Chow, V.T.K.; Teow, S.; Abrenica, B.; Booth, S.A.; Booth, T.F.; Mirazimi, A.; Lal, S.K. SARS-CoV 9b Protein Diffuses into Nucleus, Undergoes Active Crm1 Mediated Nucleocytoplasmic Export and Triggers Apoptosis When Retained in the Nucleus. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsoi, H.; Li, L.; Chen, Zhefan S.; Lau, K.-F.; Tsui, S.K.W.; Chan, H.Y.E. The SARS-coronavirus membrane protein induces apoptosis via interfering with PDK1-PKB/Akt signalling. Biochem. J. 2014, 464, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Diego, M.L.; Nieto-Torres, J.L.; JimÈnez-GuardeÒo, J.M.; Regla-Nava, J.A.; Álvarez, E.; Oliveros, J.C.; Zhao, J.; Fett, C.; Perlman, S.; Enjuanes, L. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Envelope Protein Regulates Cell Stress Response and Apoptosis. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002315. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Y.-X.; Tan, T.H.P.; Lee, M.J.R.; Tham, P.-Y.; Gunalan, V.; Druce, J.; Birch, C.; Catton, M.; Fu, N.Y.; Yu, V.C.; et al. Induction of Apoptosis by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 7a Protein Is Dependent on Its Interaction with the Bcl-X(L) Protein. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 6346–6355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favreau, D.J.; Desforges, M.; St-Jean, J.R.; Talbot, P.J. A human coronavirus OC43 variant harboring persistence-associated mutations in the S glycoprotein differentially induces the unfolded protein response in human neurons as compared to wild-type virus. Virology 2009, 395, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diemer, C.; Schneider, M.; Seebach, J.; Quaas, J.; Frösner, G.; Schätzl, H.M.; Gilch, S. Cell Type-Specific Cleavage of Nucleocapsid Protein by Effector Caspases during SARS Coronavirus Infection. J. Mol. Biol. 2008, 376, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

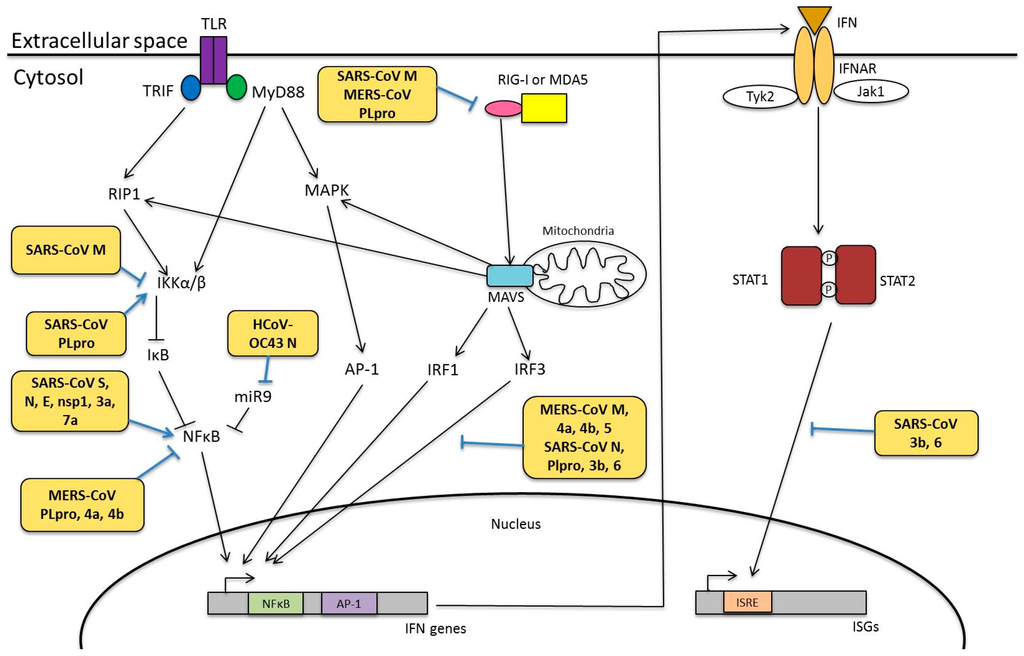

- Alcami, A.; Koszinowski, U.H. Viral mechanisms of immune evasion. Immunol. Today 2000, 21, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowie, A.G.; Unterholzner, L. Viral evasion and subversion of pattern-recognition receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, T.; Akira, S. Toll-like Receptors and Their Crosstalk with Other Innate Receptors in Infection and Immunity. Immunity 2011, 34, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, S.; Thomsen, A.R. Sensing of RNA Viruses: A Review of Innate Immune Receptors Involved in Recognizing RNA virus Invasion. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 2900–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.M.Y.; Kok, K.-H.; Jaume, M.; Cheung, T.K.W.; Yip, T.-F.; Lai, J.C.C.; Guan, Y.; Webster, R.G.; Jin, D.Y.; Peiris, J.S. Toll-like receptor 10 is involved in induction of innate immune responses to influenza virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 3793–3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, F.; Wagner, V.; Rasmussen, S.B.; Hartmann, R.; Paludan, S.R. Double-Stranded RNA Is Produced by Positive-Strand RNA Viruses and DNA Viruses but Not in Detectable Amounts by Negative-Strand RNA Viruses. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 5059–5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemmi, H.; Takeuchi, O.; Kawai, T.; Kaisho, T.; Sato, S.; Sanjo, H.; Matsumoto, M.; Hoshino, K.; Wagner, H.; Takeda, K.; et al. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature 2000, 408, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Krug, A.; Luker, G.D.; Barchet, W.; Leib, D.A.; Akira, S.; Colonna, M. Herpes simplex virus type 1 activates murine natural interferon-producing cells through toll-like receptor 9. Blood 2003, 103, 1433–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krug, A.; French, A.R.; Barchet, W.; Fischer, J.A.A.; Dzionek, A.; Pingel, J.T.; Orihuela, M.M.; Akira, S.; Yokoyama, W.M.; Colonna, M. TLR9-Dependent Recognition of MCMV by IPC and DC Generates Coordinated Cytokine Responses that Activate Antiviral NK Cell Function. Immunity 2004, 21, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, M.; Zeisel, M.B.; Jilg, N.; Paranhos-Baccalà, G.; Stoll-Keller, F.; Wakita, T.; Hafkemeyer, P.; Blum, H.E.; Barth, H.; Henneke, P.; et al. Toll-like receptor 2 senses hepatitis C virus core protein but not infectious viral particles. J. Innate Immunity 2009, 1, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bieback, K.; Lien, E.; Klagge, I.M.; Avota, E.; Schneider-Schaulies, J.; Duprex, W.P.; Wagner, H.; Kirschning, C.J.; Ter Meulen, V.; Schneider-Schaulies, S. Hemagglutinin Protein of Wild-Type Measles Virus Activates Toll-Like Receptor 2 Signaling. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 8729–8736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rallabhandi, P.; Phillips, R.L.; Boukhvalova, M.S.; Pletneva, L.M.; Shirey, K.A.; Gioannini, T.L.; Weiss, J.P.; Chow, J.C.; Hawkins, L.D.; Vogel, S.N.; et al. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Fusion Protein-Induced Toll-Like Receptor 4 (TLR4) Signaling Is Inhibited by the TLR4 Antagonists Rhodobacter sphaeroides Lipopolysaccharide and Eritoran (E5564) and Requires Direct Interaction with MD-2. mBio 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Haij, N.; Leghmari, K.; Planès, R.; Thieblemont, N.; Bahraoui, E. HIV-1 Tat protein binds to TLR4-MD2 and signals to induce TNF-α and IL-10. Retrovirology 2013, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, H.; Kawai, T.; Akira, S. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 388, 621–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honda, K.; Taniguchi, T. IRFs: Master regulators of signalling by Toll-like receptors and cytosolic pattern-recognition receptors. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006, 6, 644–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.; Wang, H.; Hajishengallis, G.N.; Martin, M. TLR-signaling Networks: An Integration of Adaptor Molecules, Kinases, and Cross-talk. J. Dent. Res. 2011, 90, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, L.A.J.; Golenbock, D.; Bowie, A.G. The history of Toll-like receptors [mdash] redefining innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoneyama, M.; Kikuchi, M.; Matsumoto, K.; Imaizumi, T.; Miyagishi, M.; Taira, K.; Foy, E.; Loo, Y.M.; Gale, M., Jr.; Akira, S.; et al. Shared and Unique Functions of the DExD/H-Box Helicases RIG-I, MDA5, and LGP2 in Antiviral Innate Immunity. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 2851–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, K.R.; Bruns, A.M.; Horvath, C.M. MDA5 and LGP2: Accomplices and Antagonists of Antiviral Signal Transduction. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 8194–8200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh, T.; Kato, H.; Kumagai, Y.; Yoneyama, M.; Sato, S.; Matsushita, K.; Tsujimura, T.; Fujita, T.; Akira, S.; Takeuchi, O. LGP2 is a positive regulator of RIG-I- and MDA5-mediated antiviral responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 1512–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, G.; Zheng, H. The Laboratory of Genetics and Physiology 2: Emerging Insights into the Controversial Functions of This RIG-I-Like Receptor. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Park, H.-S.; Pyo, H.-M.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, Y. Influenza A Virus Panhandle Structure Is Directly Involved in RIG-I Activation and Interferon Induction. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 6067–6079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gack, M.U. Mechanisms of RIG-I-like Receptor Activation and Manipulation by Viral Pathogens. J. Virol. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanneganti, T.-D. Central roles of NLRs and inflammasomes in viral infection. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 688–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Callaway, J.B.; Ting, J.P.Y. Inflammasomes: Mechanism of action, role in disease, and therapeutics. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivashkiv, L.B.; Donlin, L.T. Regulation of type I interferon responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoggins, J.W.; Rice, C.M. Interferon-stimulated genes and their antiviral effector functions. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2011, 1, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kindler, E.; Jónsdóttir, H.R.; Muth, D.; Hamming, O.J.; Hartmann, R.; Rodriguez, R.; Geffers, R.; Fouchier, R.A.; Drosten, C.; Müller, M.A.; et al. Efficient Replication of the Novel Human Betacoronavirus EMC on Primary Human Epithelium Highlights Its Zoonotic Potential. mBio 2013, 4, e00611–e00612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frieman, M.; Heise, M.; Baric, R. SARS coronavirus and innate immunity. Virus Res. 2008, 133, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clementz, M.A.; Chen, Z.; Banach, B.S.; Wang, Y.; Sun, L.; Ratia, K.; Baez-Santos, Y.M.; Wang, J.; Takayama, J.; Ghosh, A.K.; et al. Deubiquitinating and Interferon Antagonism Activities of Coronavirus Papain-Like Proteases. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 4619–4629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, S.K.P.; Lau, C.C.Y.; Chan, K.-H.; Li, C.P.Y.; Chen, H.; Jin, D.-Y.; Chan, J.F.; Woo, P.C.; Yuen, K.Y. Delayed induction of proinflammatory cytokines and suppression of innate antiviral response by the novel Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: Implications for pathogenesis and treatment. J. Gen. Virol. 2013, 94, 2679–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, C.Y.; Poon, L.L.M.; Ng, I.H.Y.; Luk, W.; Sia, S.-F.; Wu, M.H.S.; Chan, K.H.; Yuen, K.Y.; Gordon, S.; Guan, Y.; et al. Cytokine Responses in Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-Infected Macrophages In Vitro: Possible Relevance to Pathogenesis. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 7819–7826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randall, R.E.; Goodbourn, S. Interferons and viruses: An interplay between induction, signalling, antiviral responses and virus countermeasures. J. Gen. Virol. 2008, 89, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funk, C.J.; Wang, J.; Ito, Y.; Travanty, E.A.; Voelker, D.R.; Holmes, K.V.; Mason, R.J. Infection of human alveolar macrophages by human coronavirus strain 229E. J. Gen. Virol. 2012, 93, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosert, R.; Kanjanahaluethai, A.; Egger, D.; Bienz, K.; Baker, S.C. RNA Replication of Mouse Hepatitis Virus Takes Place at Double-Membrane Vesicles. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 3697–3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlman, S.; Netland, J. Coronaviruses post-SARS: Update on replication and pathogenesis. Nature reviews. Microbiology 2009, 7, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Siu, K.L.; Kok, K.H.; Ng, M.H.; Poon, V.K.; Yuen, K.Y.; Zheng, B.J.; Jin, D.Y. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus M Protein Inhibits Type I Interferon Production by Impeding the Formation of TRAF3·TANK·TBK1/IKKε Complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 16202–16209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siu, K.-L.; Chan, C.-P.; Kok, K.-H.; Chiu-Yat Woo, P.; Jin, D.-Y. Suppression of innate antiviral response by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus M protein is mediated through the first transmembrane domain. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2014, 11, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Geng, H.; Deng, Y.; Huang, B.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Tan, W. The structural and accessory proteins M, ORF 4a, ORF 4b, and ORF 5 of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) are potent interferon antagonists. Protein Cell 2013, 4, 951–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopecky-Bromberg, S.A.; Martínez-Sobrido, L.; Frieman, M.; Baric, R.A.; Palese, P. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Open Reading Frame (ORF) 3b, ORF 6, and Nucleocapsid Proteins Function as Interferon Antagonists. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Pan, J.A.; Tao, J.; Guo, D. SARS-CoV nucleocapsid protein antagonizes IFN-β response by targeting initial step of IFN-β induction pathway, and its C-terminal region is critical for the antagonism. Virus Genes 2010, 42, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Lokugamage, K.G.; Rozovics, J.M.; Narayanan, K.; Semler, B.L.; Makino, S. SARS Coronavirus nsp1 Protein Induces Template-Dependent Endonucleolytic Cleavage of mRNAs: Viral mRNAs Are Resistant to nsp1-Induced RNA Cleavage. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lokugamage, K.G.; Narayanan, K.; Nakagawa, K.; Terasaki, K.; Ramirez, S.I.; Tseng, C.-T.K.; Ramirez, S.I.; Tseng, C.T.; Makino, S. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus nsp1 inhibits host gene expression by selectively targeting nuclear-transcribed mRNAs but spares mRNAs of cytoplasmic origin. J. Virol. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jauregui, A.R.; Savalia, D.; Lowry, V.K.; Farrell, C.M.; Wathelet, M.G. Identification of Residues of SARS-CoV nsp1 That Differentially Affect Inhibition of Gene Expression and Antiviral Signaling. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mielech, A.M.; Kilianski, A.; Baez-Santos, Y.M.; Mesecar, A.D.; Baker, S.C. MERS-CoV papain-like protease has deISGylating and deubiquitinating activities. Virology 2014, 450–451, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devaraj, S.G.; Wang, N.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Z.; Tseng, M.; Barretto, N.; Lin, R.; Peters, C.J.; Tseng, C.T.; Baker, S.C.; et al. Regulation of IRF-3 dependent innate immunity by the papain-like protease domain of the sars coronavirus. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 32208–32221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Chen, X.; Bian, G.; Tu, J.; Xing, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z. Proteolytic processing, deubiquitinase and interferon antagonist activities of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus papain-like protease. J. Gen. Virol. 2014, 95, 614–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuri, T.; Eriksson, K.K.; Putics, A.; Züst, R.; Snijder, E.J.; Davidson, A.D.; Siddell, S.G.; Thiel, V.; Ziebuhr, J.; Weber, F. The ADP-ribose-1′′-monophosphatase domains of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and human coronavirus 229E mediate resistance to antiviral interferon responses. J. Gen. Virol. 2011, 92, 1899–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

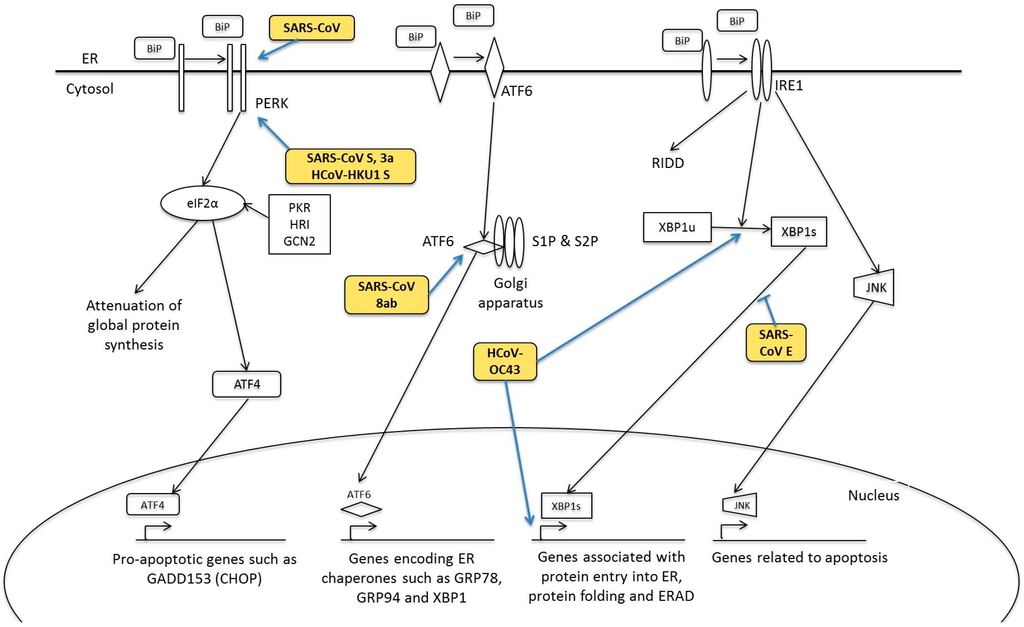

- Stevens, F.J.; Argon, Y. Protein folding in the ER. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 1999, 10, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ron, D.; Walter, P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, T.S.; Liu, D.X. Coronavirus infection, ER stress, apoptosis and innate immunity. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teske, B.F.; Wek, S.A.; Bunpo, P.; Cundiff, J.K.; McClintick, J.N.; Anthony, T.G.; Wek, R.C. The eIF2 kinase PERK and the integrated stress response facilitate activation of ATF6 during endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol. Biol. Cell 2011, 22, 4390–4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, H.P.; Zhang, Y.; Bertolotti, A.; Zeng, H.; Ron, D. Perk Is Essential for Translational Regulation and Cell Survival during the Unfolded Protein Response. Mol. Cell 2000, 5, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, H.P.; Novoa, I.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, H.; Wek, R.; Schapira, M.; Ron, D. Regulated Translation Initiation Controls Stress-Induced Gene Expression in Mammalian Cells. Mol. Cell 2000, 6, 1099–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyadomari, S.; Mori, M. Roles of CHOP//GADD153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Differ. 2003, 11, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, T.S.; Huang, M.; Liu, D.X. Coronavirus-induced ER stress response and its involvement in regulation of coronavirus-host interactions. Virus Res. 2014, 194, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minakshi, R.; Padhan, K.; Rani, M.; Khan, N.; Ahmad, F.; Jameel, S. The SARS Coronavirus 3a Protein Causes Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Induces Ligand-Independent Downregulation of the Type 1 Interferon Receptor. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e8342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C.-P.; Siu, K.-L.; Chin, K.-T.; Yuen, K.-Y.; Zheng, B.; Jin, D.-Y. Modulation of the Unfolded Protein Response by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Spike Protein. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 9279–9287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siu, K.-L.; Chan, C.-P.; Kok, K.-H.; C-Y Woo, P.; Jin, D.-Y. Comparative analysis of the activation of unfolded protein response by spike proteins of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and human coronavirus HKU1. Cell Biosci. 2014, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Fung, T.S.; Huang, M.; Fang, S.G.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, D.X. Upregulation of CHOP/GADD153 during Coronavirus Infectious Bronchitis Virus Infection Modulates Apoptosis by Restricting Activation of the Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Pathway. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 8124–8134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Liao, Y.; Yap, P.L.; Png, K.J.; Tam, J.P.; Liu, D.X. Inhibition of Protein Kinase R Activation and Upregulation of GADD34 Expression Play a Synergistic Role in Facilitating Coronavirus Replication by Maintaining De Novo Protein Synthesis in Virus-Infected Cells. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 12462–12472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, M.; Luo, S.; Baumeister, P.; Huang, J.-M.; Gogia, R.K.; Li, M.; Lee, A.S. Underglycosylation of ATF6 as a Novel Sensing Mechanism for Activation of the Unfolded Protein Response. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 11354–11363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadanaka, S.; Okada, T.; Yoshida, H.; Mori, K. Role of Disulfide Bridges Formed in the Luminal Domain of ATF6 in Sensing Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007, 27, 1027–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schröder, M.; Kaufman, R.J. The mammalian unfolded protein response. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005, 74, 739–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, H.; Matsui, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Okada, T.; Mori, K. XBP1 mRNA Is Induced by ATF6 and Spliced by IRE1 in Response to ER Stress to Produce a Highly Active Transcription Factor. Cell 2001, 107, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, S.-C.; Chao, C.-Y.; Jeng, K.-S.; Yang, J.-Y.; Lai, M.M.C. The 8ab protein of SARS-CoV is a luminal ER membrane-associated protein and induces the activation of ATF6. Virology 2009, 387, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oostra, M.; de Haan, C.A.M.; Rottier, P.J.M. The 29-Nucleotide Deletion Present in Human but Not in Animal Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronaviruses Disrupts the Functional Expression of Open Reading Frame 8. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 13876–13888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szegezdi, E.; Logue, S.E.; Gorman, A.M.; Samali, A. Mediators of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. EMBO Rep. 2006, 7, 880–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, K. Signalling Pathways in the Unfolded Protein Response: Development from Yeast to Mammals. J. Biochem. 2009, 146, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Credle, J.J.; Finer-Moore, J.S.; Papa, F.R.; Stroud, R.M.; Walter, P. On the mechanism of sensing unfolded protein in the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 18773–18784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, B.M.; Walter, P. Unfolded Proteins Are Ire1-Activating Ligands That Directly Induce the Unfolded Protein Response. Science 2011, 333, 1891–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prischi, F.; Nowak, P.R.; Carrara, M.; Ali, M.M.U. Phosphoregulation of Ire1 RNase splicing activity. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, B.; Lee, S.-M.; Chen, A.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, D.D.; Kannan, K.; Ortmann, R.A.; Fang, D. Synoviolin promotes IRE1 ubiquitination and degradation in synovial fibroblasts from mice with collagen-induced arthritis. EMBO Rep. 2008, 9, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, H.; Oku, M.; Suzuki, M.; Mori, K. pXBP1(U) encoded in XBP1 pre-mRNA negatively regulates unfolded protein response activator pXBP1(S) in mammalian ER stress response. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 172, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, A.B.; Koong, A.C.; Niwa, M. Ire1 Has Distinct Catalytic Mechanisms for XBP1/HAC1 Splicing and RIDD. Cell Rep. 2014, 9, 850–858. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, F.; Schmid, J.; Dussmann, H.; Concannon, C.G.; Prehn, J.H.M. Imaging of single cell responses to ER stress indicates that the relative dynamics of IRE1/XBP1 and PERK/ATF4 signalling rather than a switch between signalling branches determine cell survival. Cell Death Differ. 2015, 22, 1502–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urano, F.; Wang, X.; Bertolotti, A.; Zhang, Y.; Chung, P.; Harding, H.P.; Ron, D. Coupling of Stress in the ER to Activation of JNK Protein Kinases by Transmembrane Protein Kinase IRE1. Science 2000, 287, 664–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Versteeg, G.A.; van de Nes, P.S.; Bredenbeek, P.J.; Spaan, W.J.M. The Coronavirus Spike Protein Induces Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Upregulation of Intracellular Chemokine mRNA Concentrations. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 10981–10990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, T.S.; Liao, Y.; Liu, D.X. The Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Sensor IRE1α Protects Cells from Apoptosis Induced by the Coronavirus Infectious Bronchitis Virus. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 12752–12764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhillon, A.S.; Hagan, S.; Rath, O.; Kolch, W. MAP kinase signalling pathways in cancer. Oncogene 0000, 26, 3279–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, R.J. Signal Transduction to the Nucleus by MAP Kinase. In Signaling Networks and Cell Cycle Control: The Molecular Basis of Cancer and Other Diseases; Gutkind, J.S., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Panteva, M.; Korkaya, H.; Jameel, S. Hepatitis viruses and the MAPK pathway: Is this a survival strategy? Virus Res. 2003, 92, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, J.S.C.; Ley, S.C. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keshet, Y.; Seger, R. The MAP Kinase Signaling Cascades: A System of Hundreds of Components Regulates a Diverse Array of Physiological Functions. In MAP Kinase Signaling Protocols, 2nd ed.; Peger, R., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani, T.; Fukushi, S.; Murakami, M.; Hirano, T.; Saijo, M.; Kurane, I.; Morikawa, S. Tyrosine dephosphorylation of STAT3 in SARS coronavirus-infected Vero E6 cells. FEBS Lett. 2004, 577, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizutani, T.; Fukushi, S.; Saijo, M.; Kurane, I.; Morikawa, S. Phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and its downstream targets in SARS coronavirus-infected cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 319, 1228–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, I.Y.; Chang, S.C.; Wu, H.-Y.; Yu, T.-C.; Wei, W.-C.; Lin, S.; Chien, C.L.; Chang, M.F. Upregulation of the Chemokine (C-C Motif) Ligand 2 via a Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Spike-ACE2 Signaling Pathway. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 7703–7712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizutani, T.; Fukushi, S.; Saijo, M.; Kurane, I.; Morikawa, S. Regulation of p90RSK phosphorylation by SARS-CoV infection in Vero E6 cells. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 1417–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Li, W.; Wu, J.; Germann, U.A.; Su, M.S.; Kuida, K.; Boucher, D.M. Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase 2 Is Necessary for Mesoderm Differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 12759–12764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.T.-C.; Chien, S.-C.; Chen, I.Y.; Lai, C.-T.; Tsay, Y.-G.; Chang, S.C.; Chang, M.F. Surface vimentin is critical for the cell entry of SARS-CoV. J. Biomed.Sci. 2016, 23, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Robidoux, J.; Daniel, K.W.; Guzman, G.; Floering, L.M.; Collins, S. Requirement of Vimentin Filament Assembly for β3-Adrenergic Receptor Activation of ERK MAP Kinase and Lipolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 9244–9250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.-J.; Liu, C.Y.-Y.; Chiang, B.-L.; Chao, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-C. Induction of IL-8 Release in Lung Cells via Activator Protein-1 by Recombinant Baculovirus Displaying Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Coronavirus Spike Proteins: Identification of Two Functional Regions. J. Immunol. 2004, 173, 7602–7614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.-W.; Lai, C.-C.; Ping, J.-F.; Tsai, F.-J.; Wan, L.; Lin, Y.-J.; Kung, S.H.; Lin, C.W. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus papain-like protease suppressed alpha interferon-induced responses through downregulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1-mediated signalling pathways. J. Gen. Virol. 2011, 92, 1127–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varshney, B.; Lal, S. SARS-CoV Accessory Protein 3b Induces AP-1 Transcriptional Activity through Activation of JNK and ERK Pathways. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 5419–5425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kindrachuk, J.; Ork, B.; Hart, B.J.; Mazur, S.; Holbrook, M.R.; Frieman, M.B.; Traynor, D.; Johnson, R.F.; Dyall, J.; Kuhn, J.H.; et al. Antiviral Potential of ERK/MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Modulation for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Infection as Identified by Temporal Kinome Analysis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 1088–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kono, M.; Tatsumi, K.; Imai, A.M.; Saito, K.; Kuriyama, T.; Shirasawa, H. Inhibition of human coronavirus 229E infection in human epithelial lung cells (L132) by chloroquine: Involvement of p38 MAPK and ERK. Antivir. Res. 2008, 77, 150–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizutani, T.; Fukushi, S.; Saijo, M.; Kurane, I.; Morikawa, S. JNK and PI3k/Akt signaling pathways are required for establishing persistent SARS-CoV infection in Vero E6 cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1741, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanzawa, N.; Nishigaki, K.; Hayashi, T.; Ishii, Y.; Furukawa, S.; Niiro, A.; Yasui, F.; Kohara, M.; Morita, K.; Matsushima, K.; et al. Augmentation of chemokine production by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 3a/X1 and 7a/X4 proteins through NF-κB activation. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 6807–6812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Yang, Y.; Gu, C.; Yue, Y.; Wu, K.K.; Wu, J.; Zhu, Y. Spike protein of SARS-CoV stimulates cyclooxygenase-2 expression via both calcium-dependent and calcium-independent protein kinase C pathways. FASEB J. 2007, 21, 1586–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, T.S. Molecular Characterization of Cellular Stress Responses during Coronavirus Infection. Ph.D. Thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, Singapore, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kopecky-Bromberg, S.A.; Martinez-Sobrido, L.; Palese, P. 7a Protein of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Inhibits Cellular Protein Synthesis and Activates p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 785–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.-J.; Teng, E.; Shen, S.; Tan, T.H.P.; Goh, P.-Y.; Fielding, B.C.; Ooi, E.E.; Tan, H.C.; Lim, S.G.; Hong, W. A Novel Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Protein, U274, Is Transported to the Cell Surface and Undergoes Endocytosis. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 6723–6734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Guardeño, J.M.; Nieto-Torres, J.L.; DeDiego, M.L.; Regla-Nava, J.A.; Fernandez-Delgado, R.; Castaño-Rodriguez, C.; Enjuanes, L. The PDZ-Binding Motif of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Envelope Protein Is a Determinant of Viral Pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.-H.; Chen, R.-F.; Liu, J.-W.; Yeh, W.-T.; Chang, J.-C.; Liu, P.-M.; Eng, H.L.; Lin, M.C.; Yang, K.D. Altered p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Expression in Different Leukocytes with Increment of Immunosuppressive Mediators in Patients with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 7841–7847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoro, M.; Rossi, A.; Amici, C. NEW EMBO MEMBER’S REVIEW: NF-κB and virus infection: Who controls whom. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 2552–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoesel, B.; Schmid, J.A. The complexity of NF-κB signaling in inflammation and cancer. Mol. Cancer 2013, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiscott, J.; Kwon, H.; Génin, P. Hostile takeovers: Viral appropriation of the NF-κB pathway. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 107, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.-C. Non-canonical NF-κB signaling pathway. Cell Res. 2011, 21, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Diego, M.L.; Nieto-Torres, J.L.; Regla-Nava, J.A.; Jimenez-Guardeño, J.M.; Fernandez-Delgado, R.; Fett, C.; Castaño-Rodriguez, C.; Perlman, S.; Enjuanes, L. Inhibition of NF-κB-Mediated Inflammation in Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-Infected Mice Increases Survival. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dosch, S.F.; Mahajan, S.D.; Collins, A.R. SARS Coronavirus Spike Protein-Induced Innate Immune Response occurs via Activation of the NF-κB pathway in Human Monocyte Macrophages in vitro. Virus Res. 2009, 142, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Q.-J.; Ye, L.-B.; Timani, K.A.; Zeng, Y.-C.; She, Y.-L.; Ye, L.; Wu, Z.H. Activation of NF-κB by the Full-length Nucleocapsid Protein of the SARS Coronavirus. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2005, 37, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, R.; Leeson, A.; Andonov, A.; Li, Y.; Bastien, N.; Cao, J.; Osiowy, C.; Dobie, F.; Cutts, T.; Ballantine, M.; et al. Activation of AP-1 signal transduction pathway by SARS coronavirus nucleocapsid protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 311, 870–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Gao, J.; Zheng, H.; Li, B.; Kong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zeng, Y.; Ye, L. The membrane protein of SARS-CoV suppresses NF-κB activation. J. Med. Virol. 2007, 79, 1431–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, F.W.; Stephenson, K.B.; Mahony, J.; Lichty, B.D. Human Coronavirus OC43 Nucleocapsid Protein Binds MicroRNA 9 and Potentiates NF-κB Activation. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, A.H.Y.; Lee, D.C.W.; Cheung, B.K.W.; Yim, H.C.H.; Lau, A.S.Y. Role for Nonstructural Protein 1 of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus in Chemokine Dysregulation. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frieman, M.; Ratia, K.; Johnston, R.E.; Mesecar, A.D.; Baric, R.S. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Papain-Like Protease Ubiquitin-Like Domain and Catalytic Domain Regulate Antagonism of IRF3 and NF-κB Signaling. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 6689–6705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratia, K.; Kilianski, A.; Baez-Santos, Y.M.; Baker, S.C.; Mesecar, A. Structural Basis for the Ubiquitin-Linkage Specificity and deISGylating Activity of SARS-CoV Papain-Like Protease. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, K.L.; Coleman, C.M.; van der Meer, Y.; Snijder, E.J.; Frieman, M.B. The ORF4b-encoded accessory proteins of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus and two related bat coronaviruses localize to the nucleus and inhibit innate immune signalling. J. Gen. Virol. 2014, 95, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).