Electronic Energy Meter Based on a Tunnel Magnetoresistive Effect (TMR) Current Sensor

Abstract

:1. Introduction

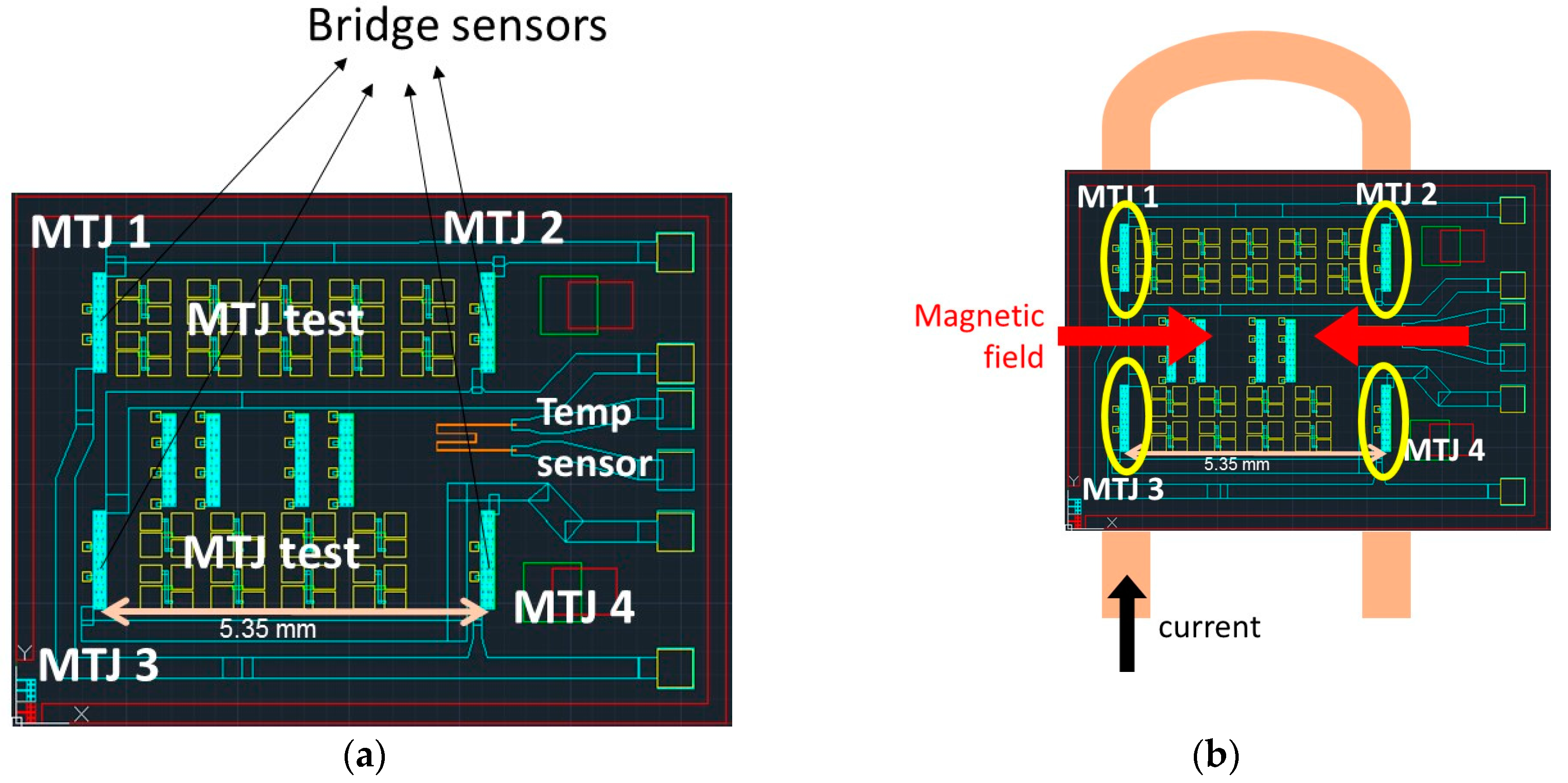

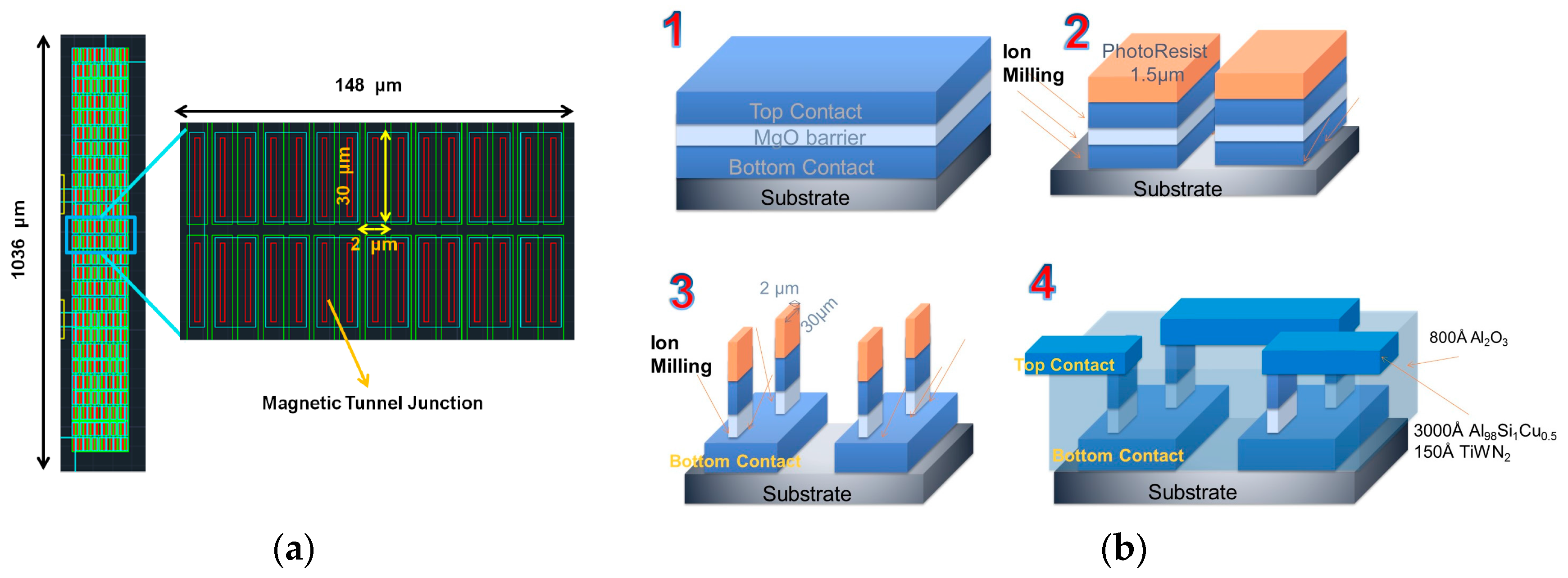

2. Sensor Description

2.1. Design and Microfabrication

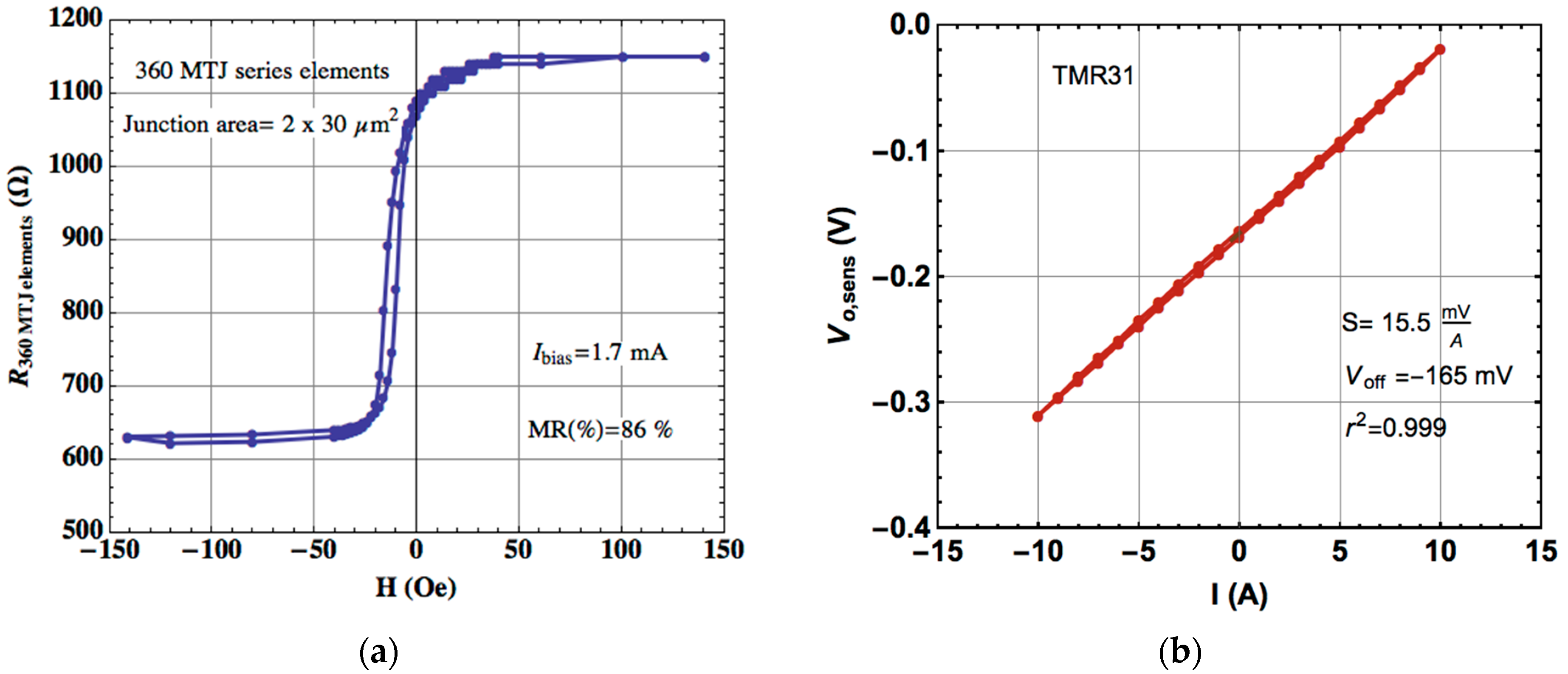

2.2. Physical and Electrical Characterization

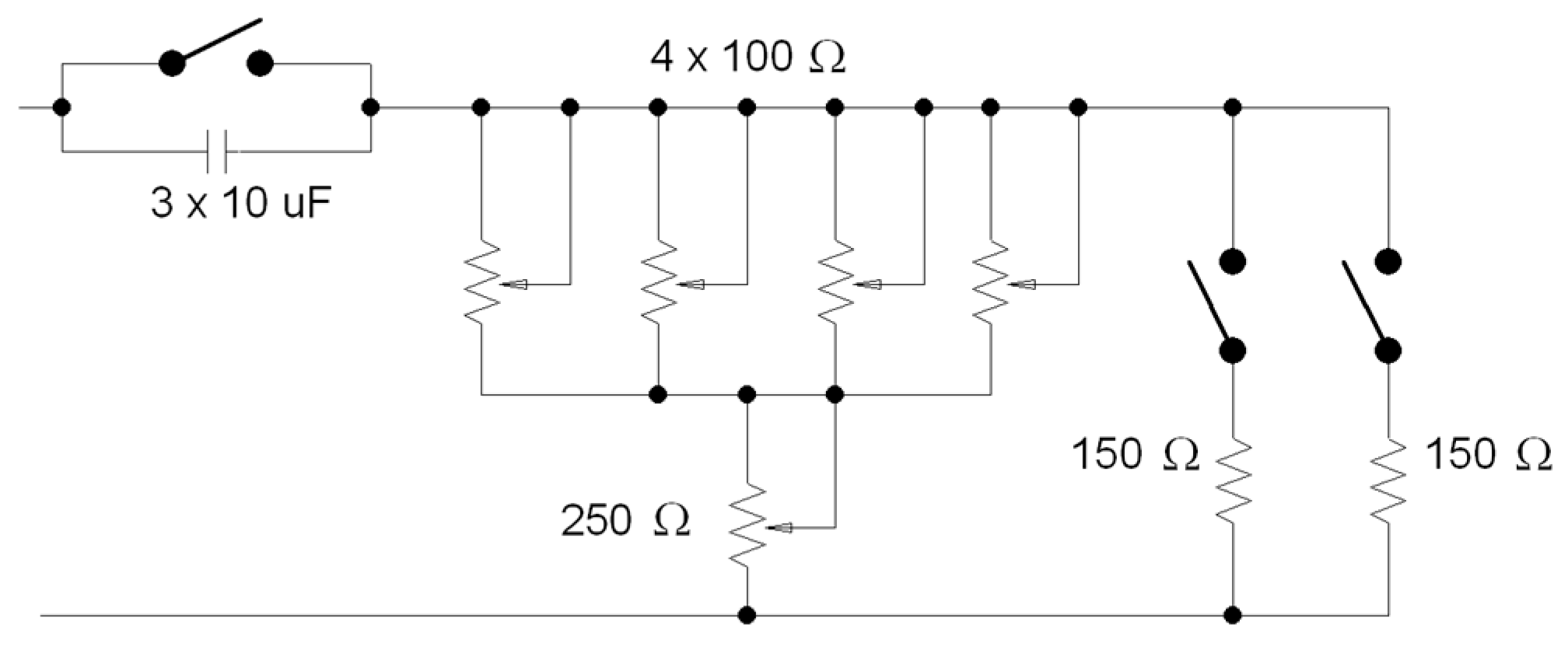

2.3. Practical Implementation

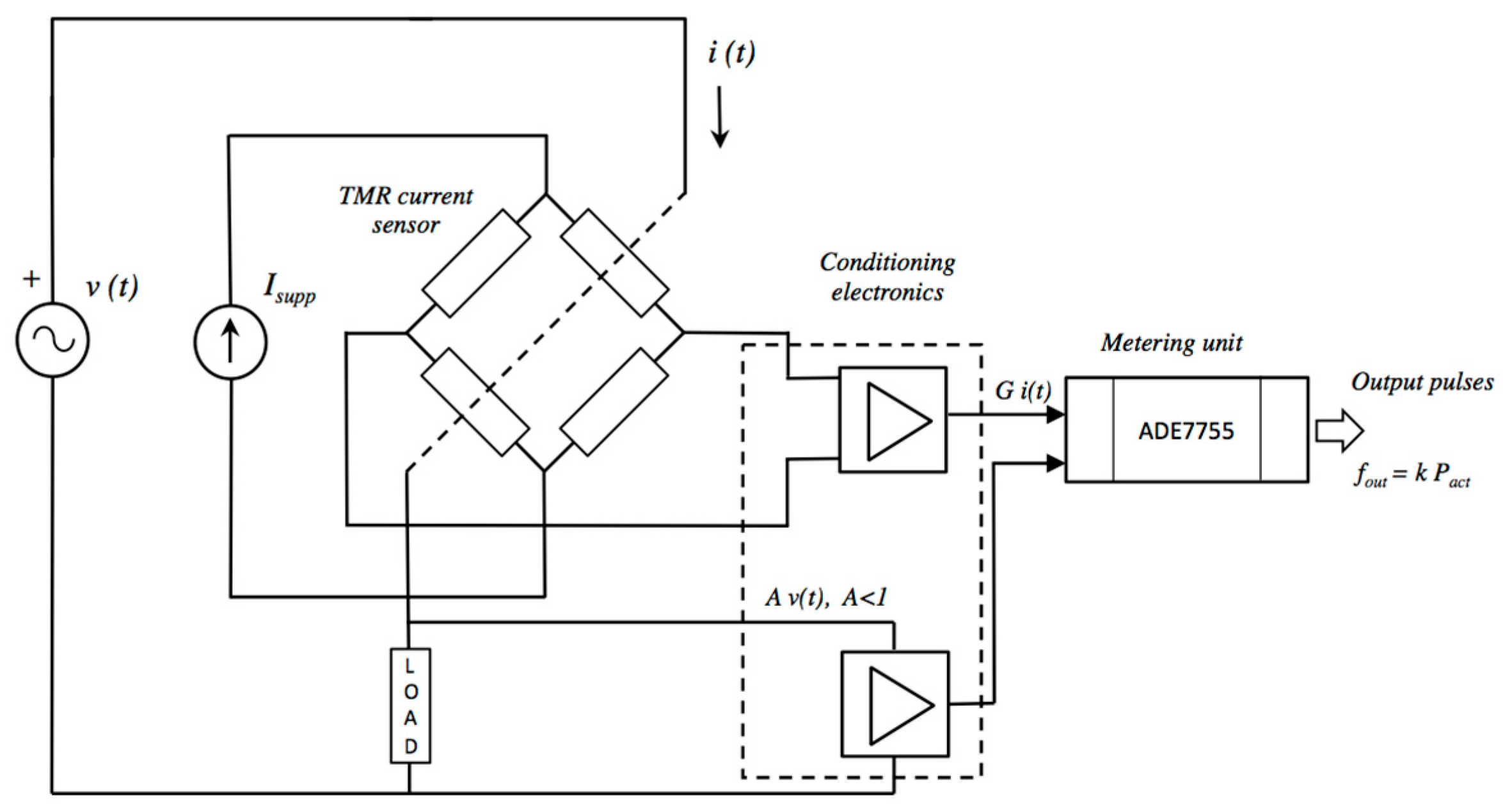

3. Description of the Electronic Energy Meter

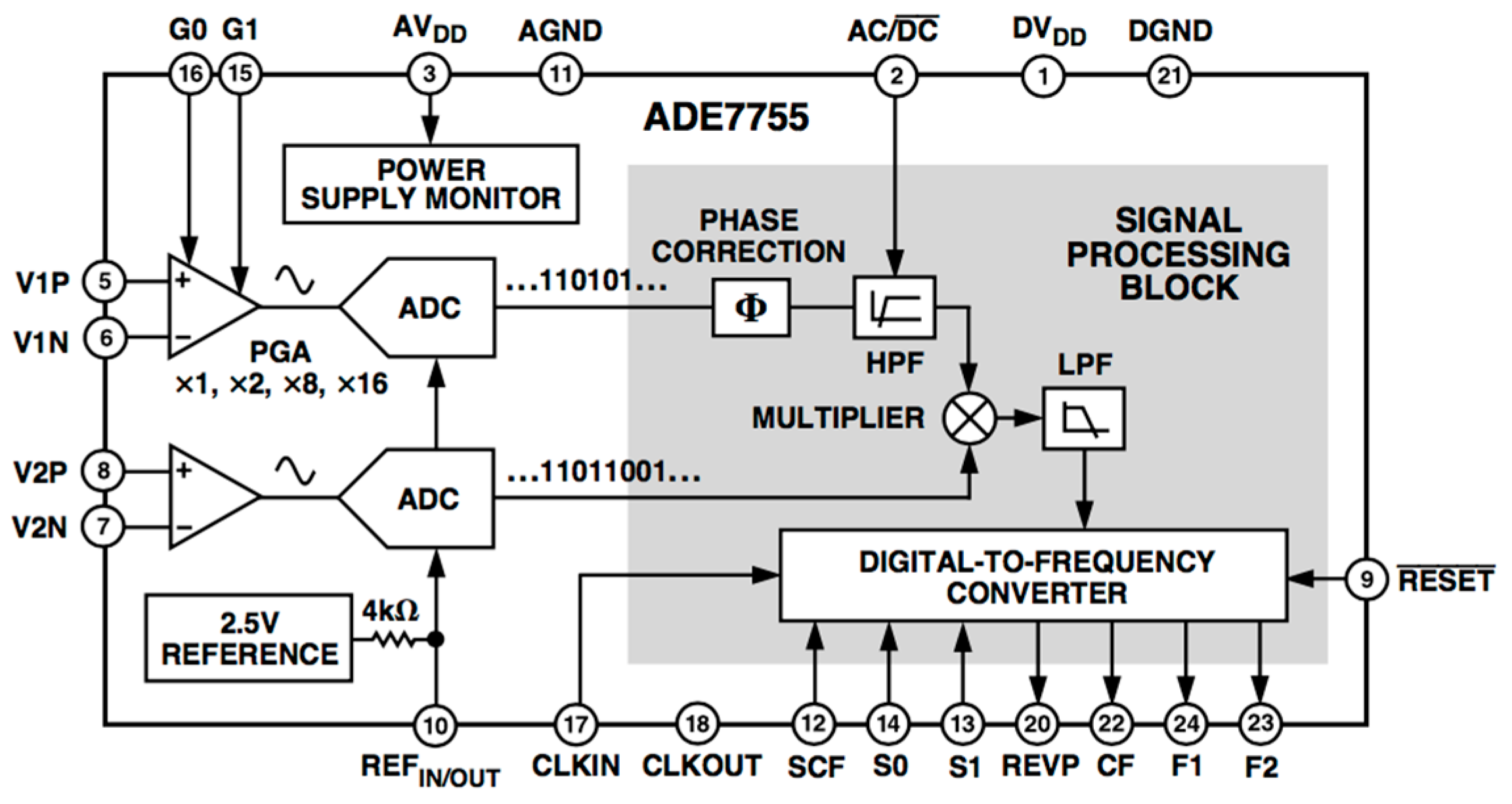

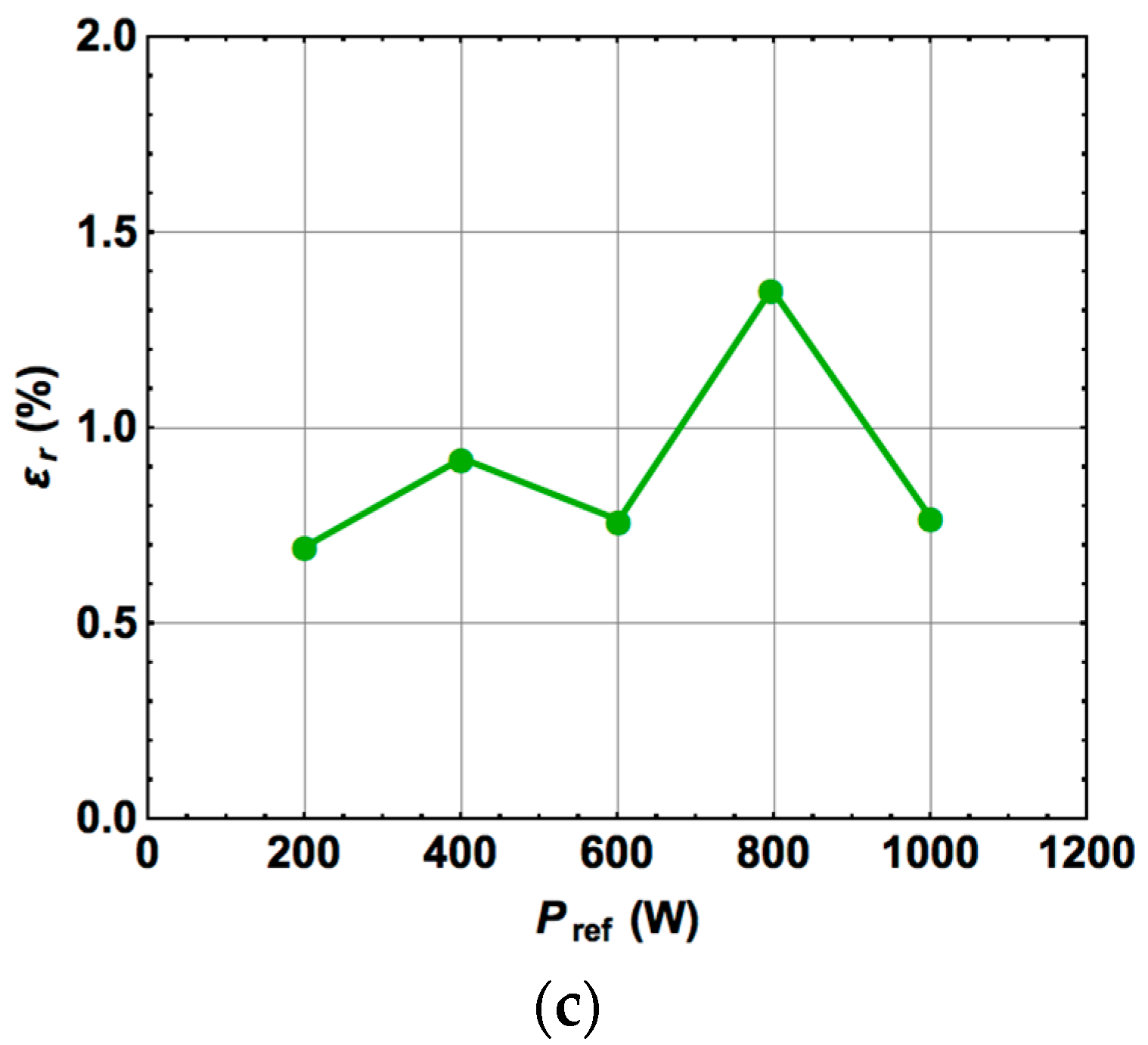

3.1. Electronic Processing Unit (Metering Section)

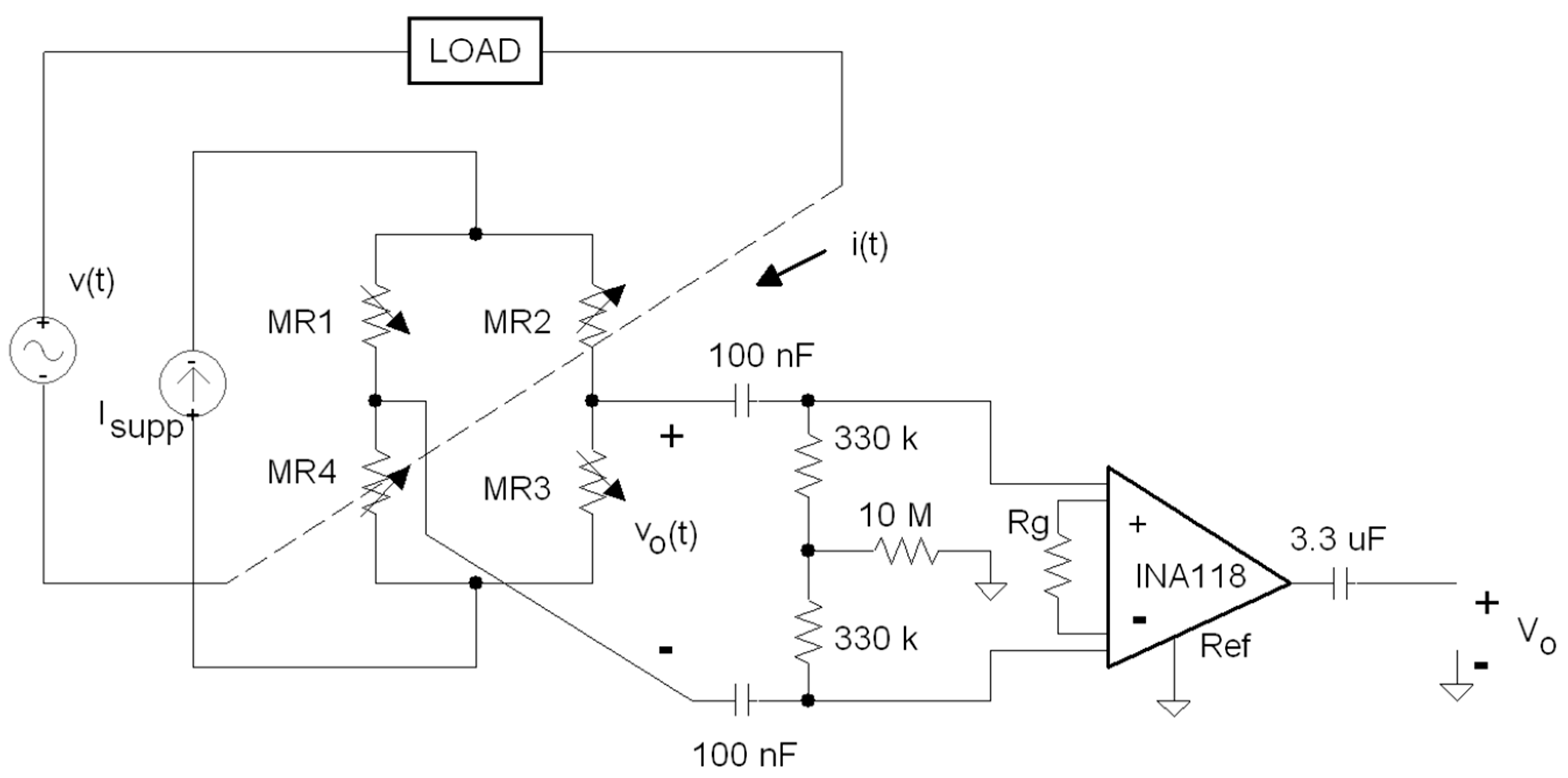

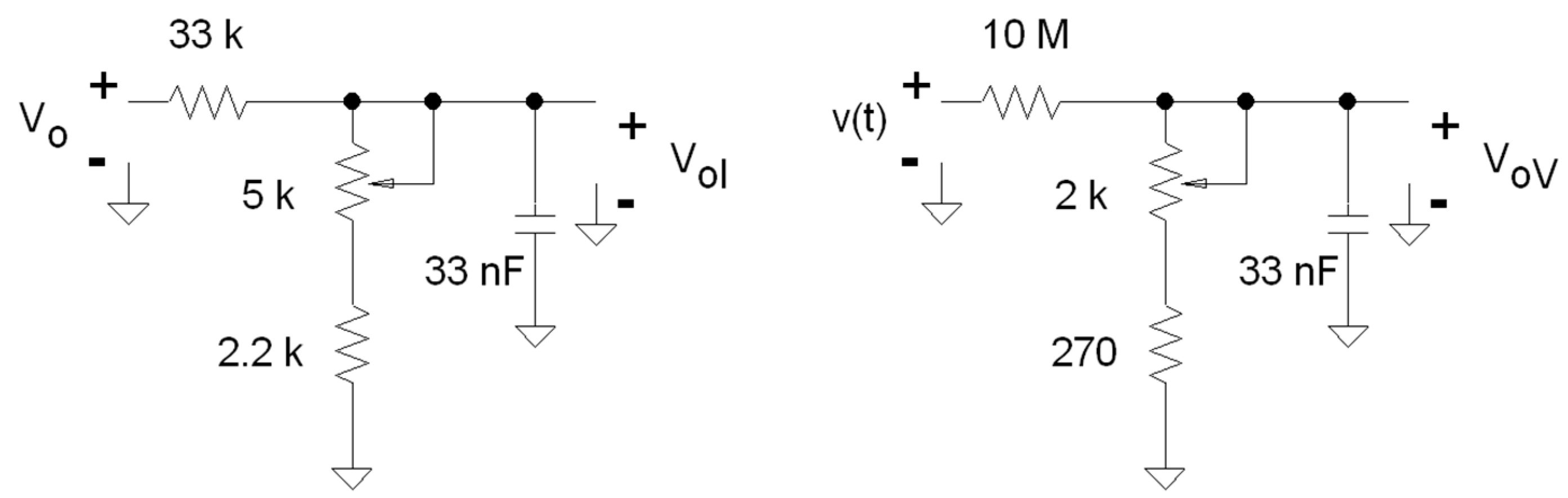

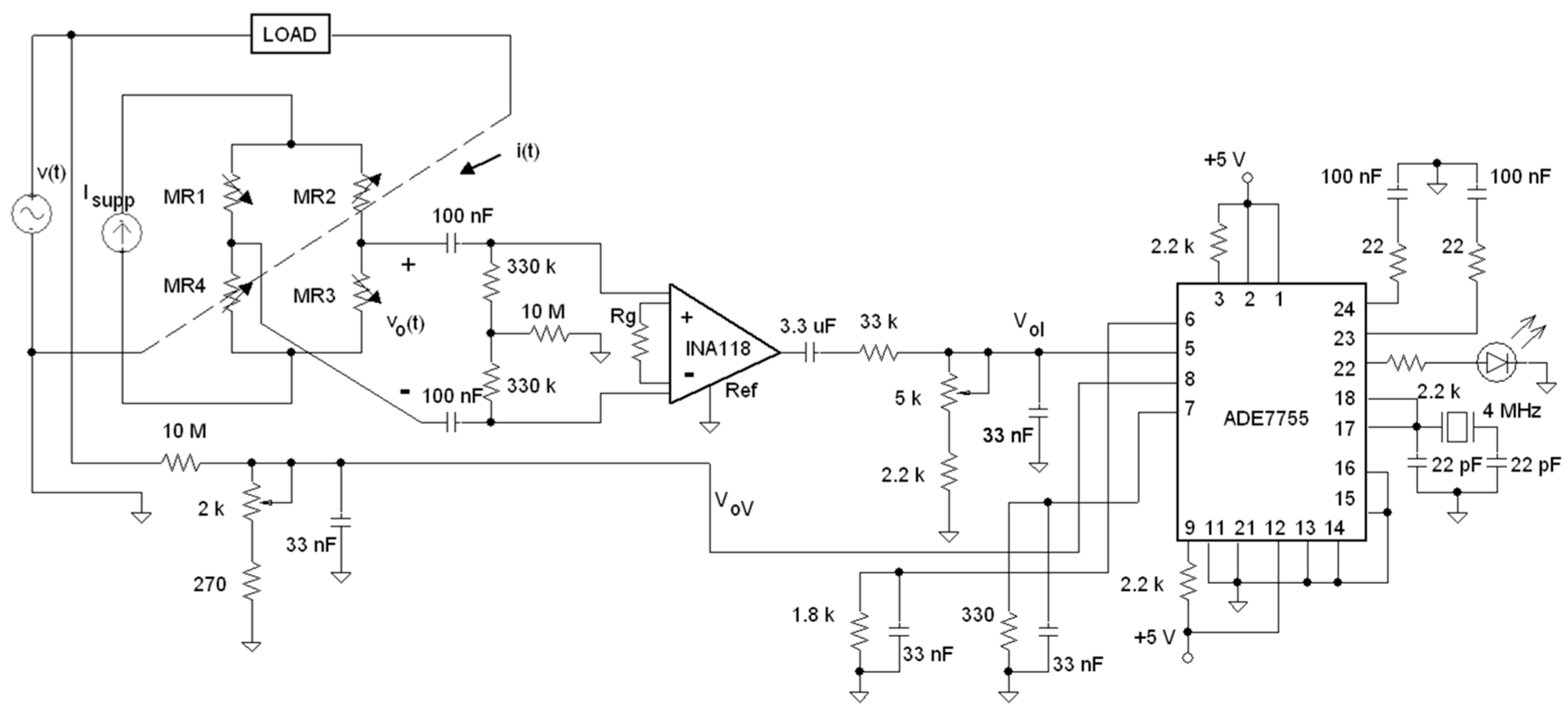

3.2. Signal Conditioning Electronics

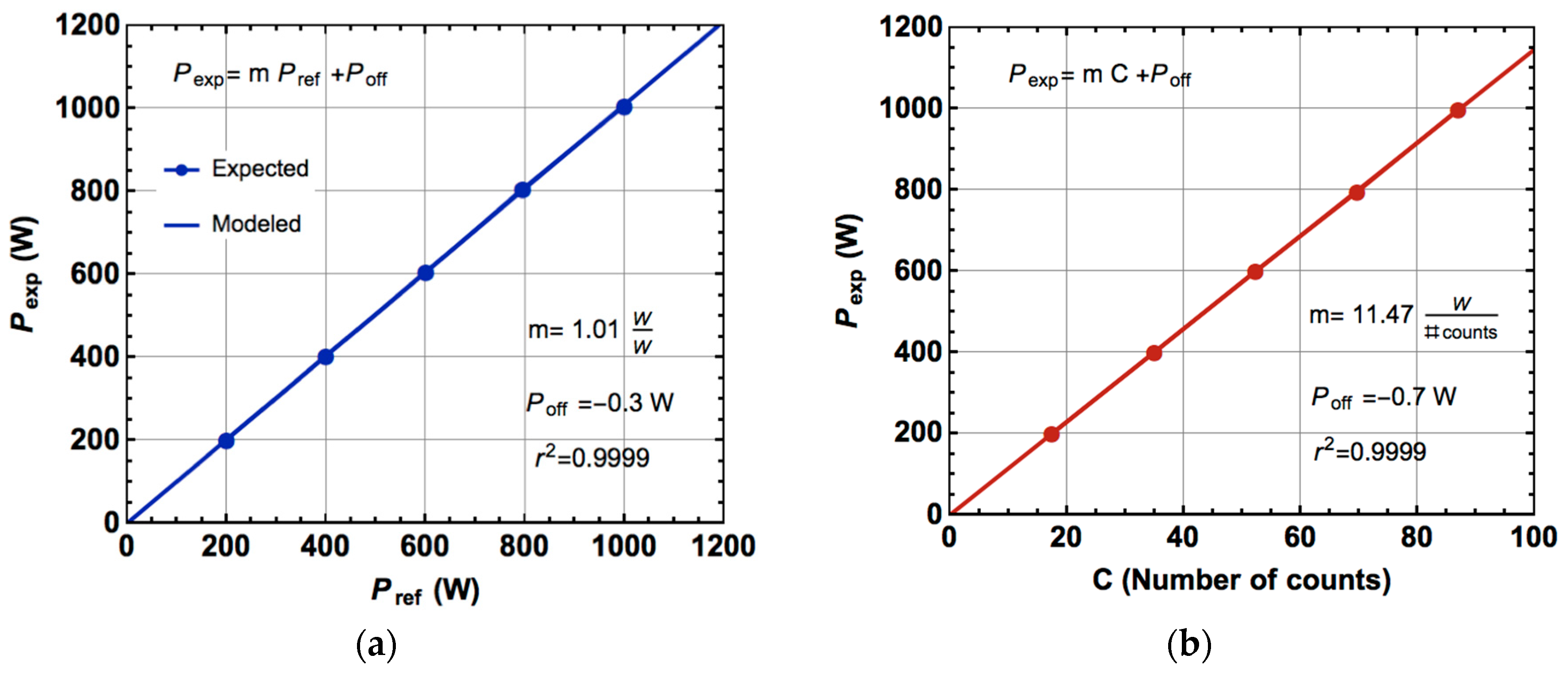

4. Experimental Results

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sze, S.M. (Ed.) Semiconductor Sensors; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1994; ISBN 0471546097. [Google Scholar]

- Magnetic Sensors International Data Book; Siemens Aktiengesellschaft: München, Germany, 1995.

- Richard, B.; Kenneth, J.O. Magnetic Sensors. In Sensors, A Comprehensive Survey; Wolfgang, G., Joachim, H., Zemel, J.N., Eds.; VCH: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 5, ISBN 978-3-527-62058-6. [Google Scholar]

- Baibich, M.N.; Broto, J.M.; Fert, A.; Nguyen Van Dau, F.; Petroff, F.; Eitenne, P.; Creuzet, G.; Friederich, A.; Chazelas, J. Giant magnetoresistance of (001)Fe/(001)Cr Magnetic Superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1988, 61, 2472–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, M.J.; Bratland, T.; Smith, C.H.; Schneider, R. A New Perspective on Magnetic Field Sensing. Sens. Mag. 1998, 15, 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.H.; Schneider, R.W. Expanding the Horizons of Magnetic Sensing: GMR. Proc. Sens. Expo. 1997, 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Daughton, J.; Chen, Y. GMR Materials for Low Field Applications. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1993, 29, 2705–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daughton, J.; Brown, J.; Chen, E.; Beech, R.; Pohm, A.; Kude, W. Magnetic Field Sensors Using GMR Multilayer. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1994, 30, 4608–4610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehanno, V.; Freitas, P.P.; Veloso, A.; Ferreira, J.; Almeida, B.; Sousa, J.B.; Kling, A.; Soares, J.C.; da Silva, M.F. Ion beam deposition of Mn-Ir spin valves. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1999, 35, 4361–4367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieny, B.; Speriosu, V.S.; Gurney, B.A.; Parkin, S.S.P.; Wilhoit, D.R.; Roche, K.P.; Metin, S.; Peterson, D.T.; Nadimi, S. Spin-Valve Effect in Soft Ferromagnetic Sandwiches. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1991, 93, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, T.; Tezuka, N. Giant magnetic tunneling effect in Fe/Al2O3/Fe junction. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1995, 139, L231–L234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodera, J.S.; Kinder, L.R.; Wong, T.M.; Meservey, R. Large Magnetoresistance at Room Temperature in Ferromagnetic Thin Film Tunnel Junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 74, 3273–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, R.C.; Sun, J.J.; Soares, V.; Freitas, P.P.; Kling, A.; DaSilva, M.F.; Soares, J.C. Large tunneling magnetoresistance enhancement by thermal anneal. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1998, 73, 3288–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederman, M. Performance of metallic antiferromagnets for use in spin-valve read sensors. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1999, 35, 794–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, S.; Hayakawa, J.; Ashizawa, Y.; Lee, Y.M.; Miura, K.; Hasegawa, H.; Tsunoda, M.; Matsukura, F.; Ohno, H. Tunnel magnetoresistance of 604% at 300 K by suppression of Ta diffusion in CoFeB/MgO/CoFeB pseudo-spin-valves annealed at high temperature. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 93, 082508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudde, S.; Farinha, G.; Leitao, D.; Ferreira, R.; Freitas, P.P.; Cardoso, S. AlOx barrier growth in magnetic tunnel junctions for sensor applications. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2016, 412, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, S.S.P.; Kaiser, C.; Panchula, A.; Rice, P.M.; Hughes, B.; Samant, M.; Yang, S.H. Giant tunneling magnetoresistance at room temperature with MgO (100) tunnel barriers. Nat. Mater. 2004, 3, 862–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, P.P.; Ferreira, R.; Cardoso, S. Spintronic Sensors. Proc. IEEE 2016, 104, 1894–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, P.P.; Ferreira, R.; Cardoso, S.; Cardoso, F. Magnetoresistive sensors. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2007, 19, 165221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.Y.; Hung, M.H.; Chang, K.W. A ZigBee-Based Power Monitoring System with Direct Load Control Capabilities. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Networking, Sensing and Control, London, UK, 15–17 April 2007; pp. 895–900. [Google Scholar]

- Loss, P.A.V.; Lamego, M.M.; Sousa, G.C.D.; Vieira, J.L.F. A single phase microcontroller based energy meter. In Proceedings of the IEEE Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference, Saint Paul, MN, USA, 18–21 May 1998; pp. 797–800. [Google Scholar]

- Jansson, P.M.; Tisa, J.; Kim, W. Instrument and Measurement Technology Education-A Case Study: Inexpensive Student-Designed Power Monitoring Instrument for Campus Submetering. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2007, 56, 1744–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vopálensky, M.; Platil, A.; Kaspar, P. Wattmeter with AMR sensor. Sens. Actuators A 2005, 123–124, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vountesmeri, V. Magnetoresistive watt-converter for measurement active power in the frequency range of 20 Hz–20 kHz. In Proceedings of the Conference Precision Electromagnetic Measurements Digest, Sidney, Australia, 14–19 May 2000; pp. 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Vountesmeri, V.; Rodríguez, J.; Carranza, R. Error source determination of a magnetoresistive active power sensor at industrial frequencies. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2002, 51, 1035–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldán, A.; Reig, C.; Cubells-Beltrán, M.D.; Roldán, J.B.; Ramírez, D.; Cardoso, S.; Freitas, P.P. Analytical compact modeling of GMR based current sensors: Application to power measurement at the IC level. Solid-State Electron. 2010, 54, 1606–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, S.; Woodward, R.C.; Ho-Ching, H.; Borle, L.J. Current Sensing Techniques: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2009, 9, 354–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripka, P. Electric current sensors: A review. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2010, 21, 112001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Moreno, J.; Ramírez Muñoz, D.; Casans Berga, S.; Navarro Antón, A.E.; Cardoso, S.; Freitas, P. A non-invasive thermal drift compensation technique applied to a spin-valve magnetoresistive current sensor. Sensors 2011, 11, 2447–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, A.; Cardoso, S.; Ferreira, R.; Paz, E.; Francis, L.; Freitas, P.; Sánchez, J.; Ramírez, D.; Ravelo, S.I. MgO Magnetic Tunnel Junction Electrical Current Sensor with Integrated Ru Thermal Sensor. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2013, 49, 3866–3869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.; Leitao, D.; Amaral, J.; Valadeiro, J.; Cardoso, S.; Freitas, P.P. Linearization strategies for high sensitivity magnetoresistive sensors. Eur. Phys. J. Appl. Phys. 2015, 72, 10601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, E.; Ferreira, R.; Freitas, P. Linearization of Magnetic Sensors with a Weakly Pinned Free Layer MTJ Stack Using a Three-Step Annealing Process. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2016, 52, 4002104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Analog. Energy. Available online: http://www.analog.com/en/applications/markets/energy.html (accessed on 22 July 2017).

- Silergy. Energy-Powering the Future. Available online: http://www.silergy.com (accessed on 22 July 2017).

- Analog. Energy Metering IC with Pulse Output. Available online: http://www.analog.com/en/products/analog-to-digital-converters/integrated-special-purpose-converters/energy-metering-ics/ade7755.html (accessed on 22 July 2017).

| Load | Pref (W) | Pexp (W) | εr(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| R, 137.5 Ω | 587.6 | 584.9 | 0.5 |

| C, 30 μF | |||

| cos ϕ = 0.75 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vidal, E.G.; Muñoz, D.R.; Arias, S.I.R.; Moreno, J.S.; Cardoso, S.; Ferreira, R.; Freitas, P. Electronic Energy Meter Based on a Tunnel Magnetoresistive Effect (TMR) Current Sensor. Materials 2017, 10, 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10101134

Vidal EG, Muñoz DR, Arias SIR, Moreno JS, Cardoso S, Ferreira R, Freitas P. Electronic Energy Meter Based on a Tunnel Magnetoresistive Effect (TMR) Current Sensor. Materials. 2017; 10(10):1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10101134

Chicago/Turabian StyleVidal, Enrique García, Diego Ramírez Muñoz, Sergio Iván Ravelo Arias, Jaime Sánchez Moreno, Susana Cardoso, Ricardo Ferreira, and Paulo Freitas. 2017. "Electronic Energy Meter Based on a Tunnel Magnetoresistive Effect (TMR) Current Sensor" Materials 10, no. 10: 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10101134