Building Responsive Health Systems to Help Communities Affected by Migration: An International Delphi Consensus

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

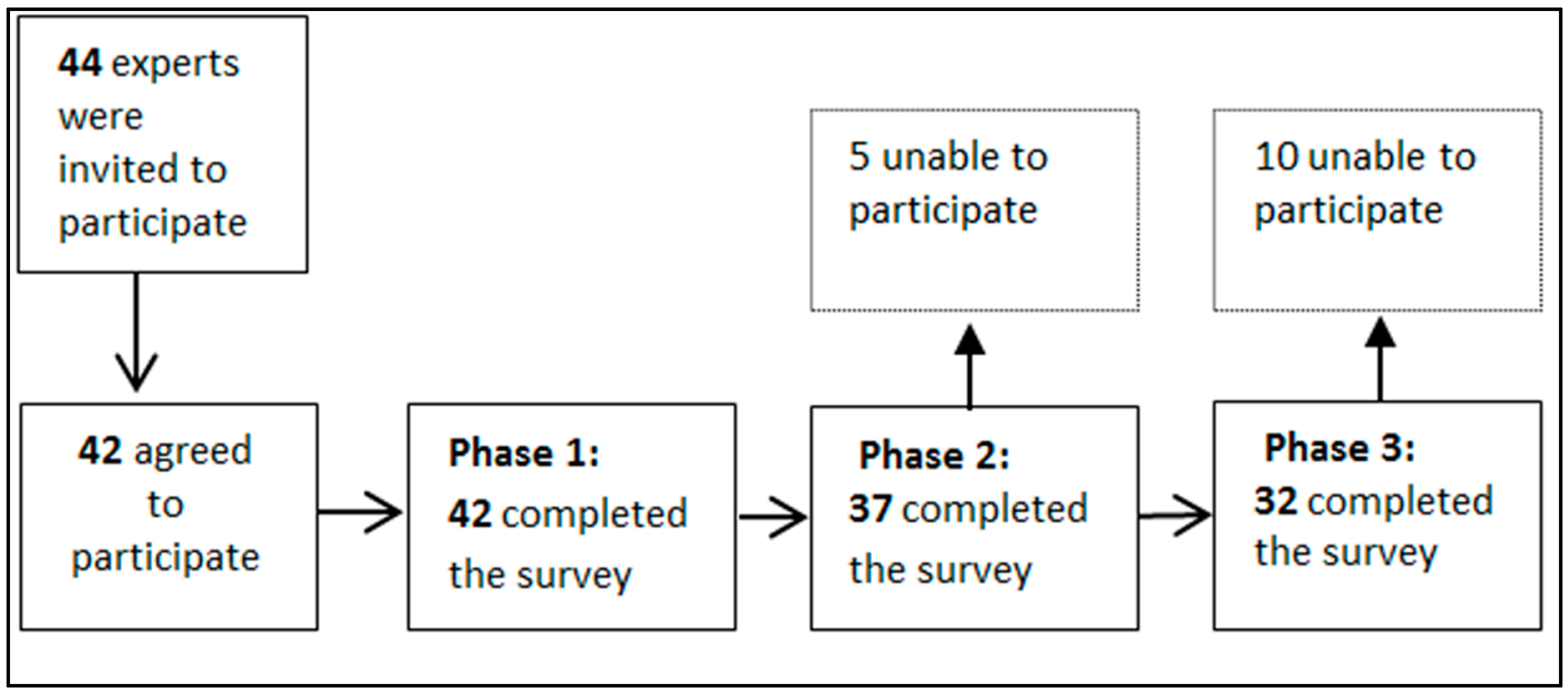

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample/Participants

2.3. Delphi Surveys

2.4. Data Analysis

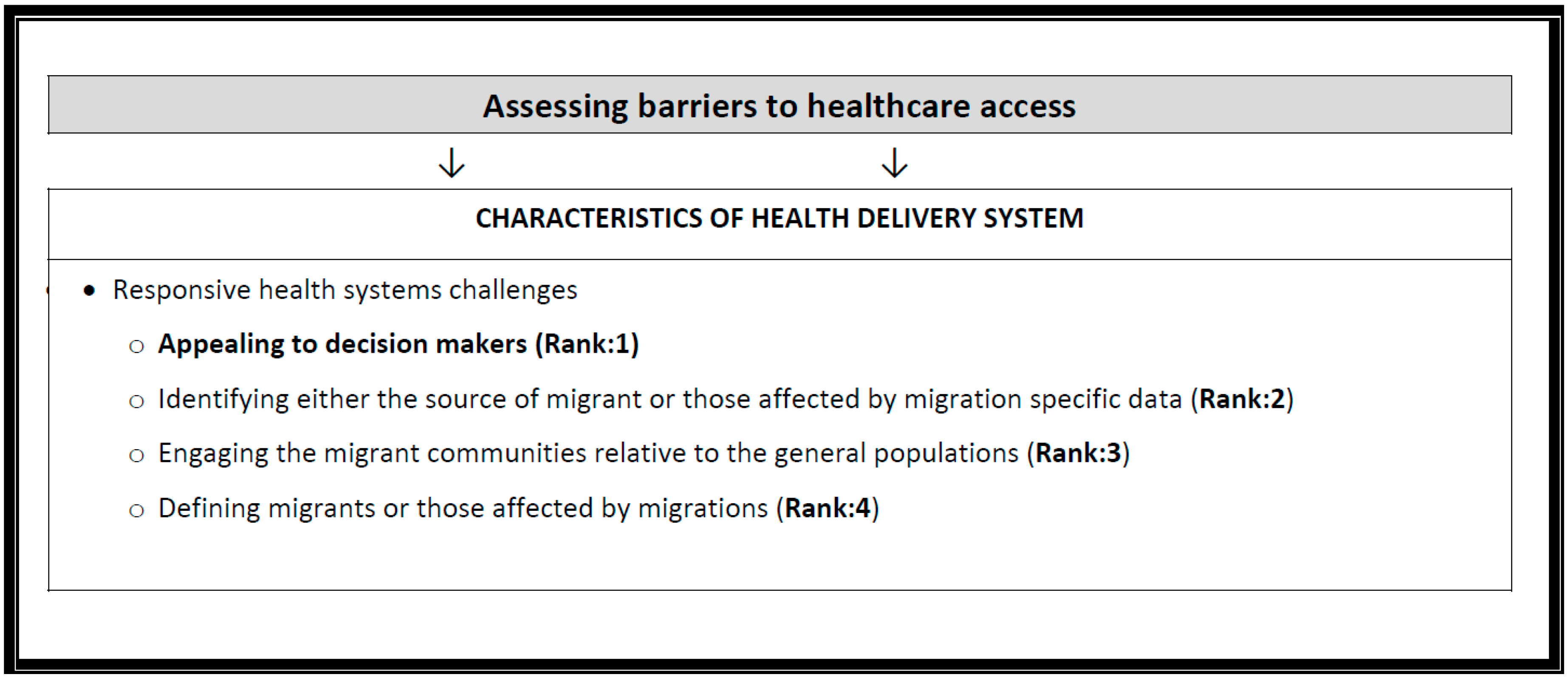

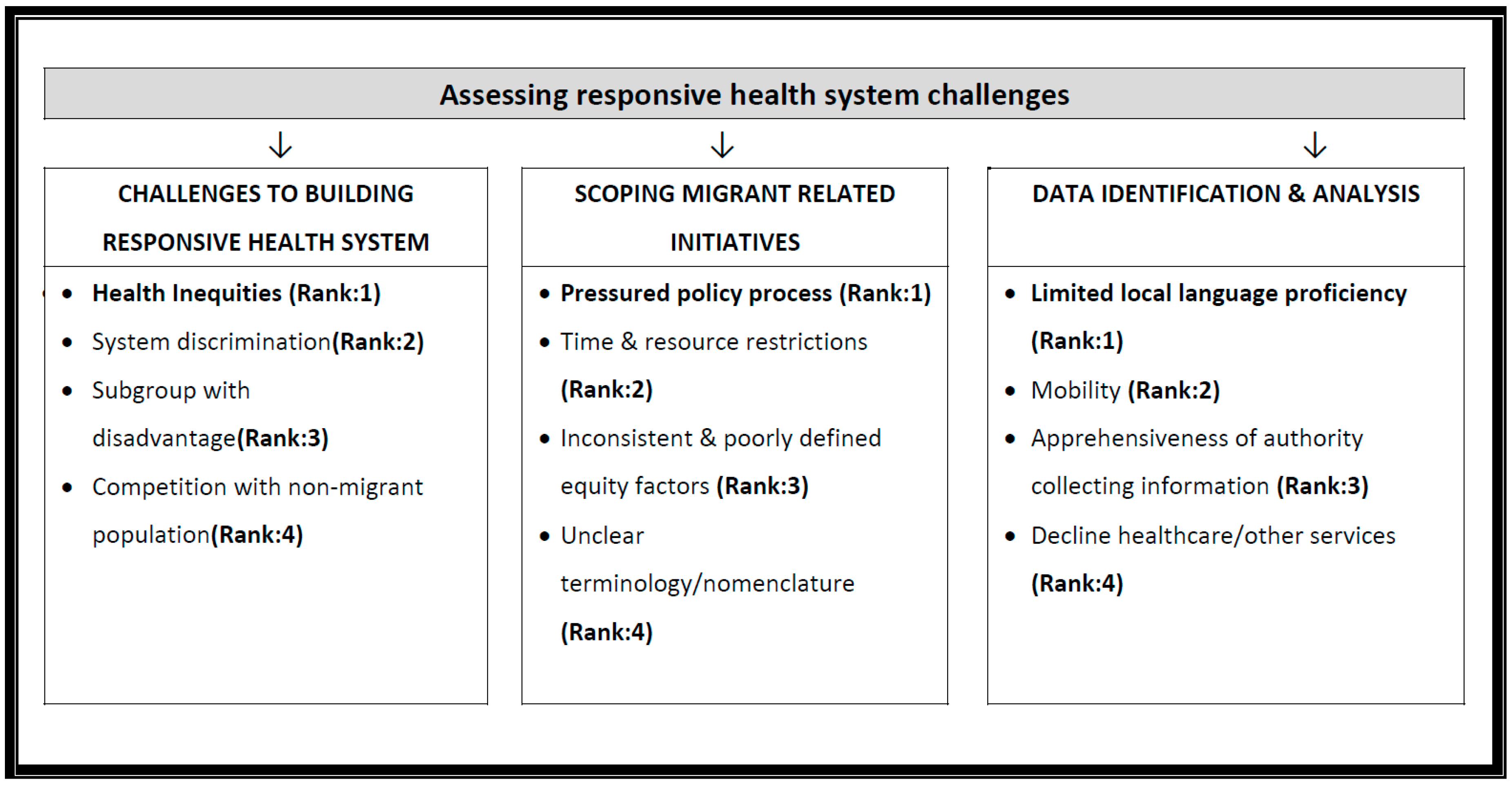

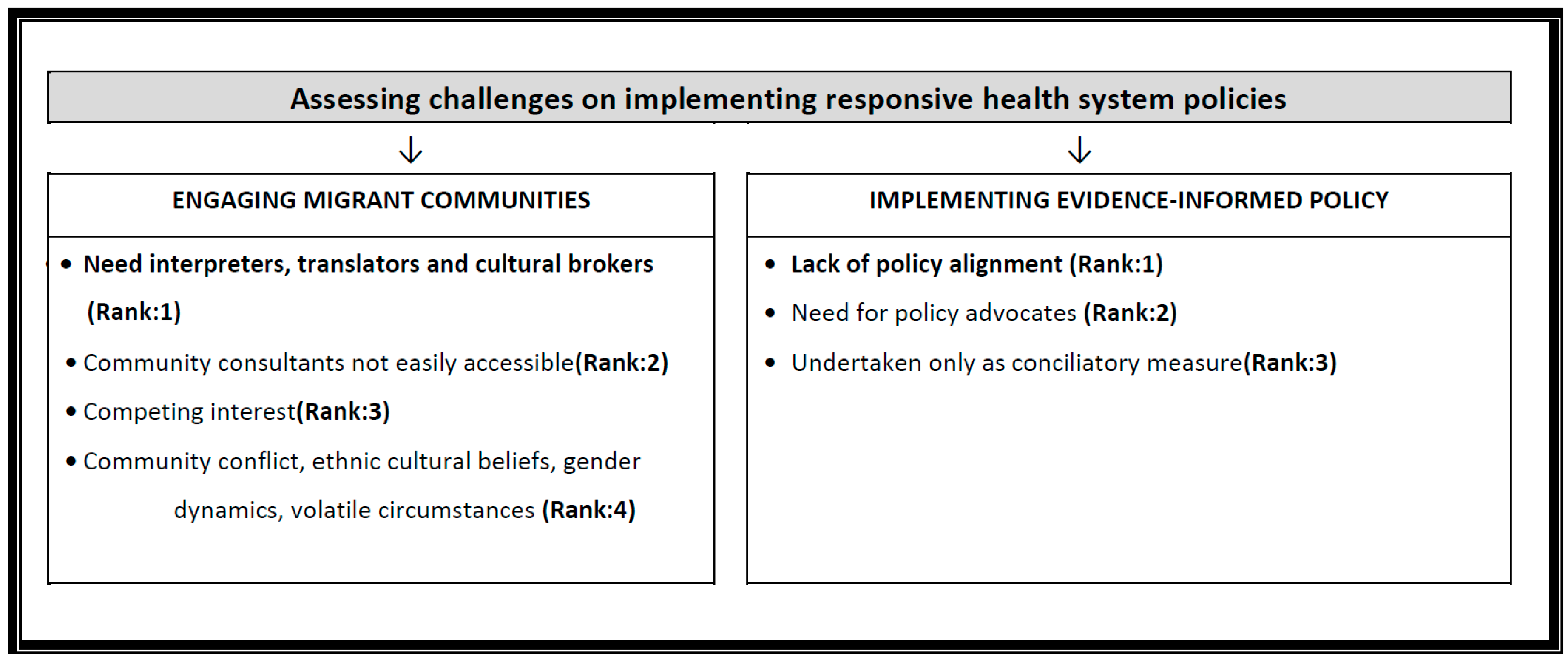

3. Results

3.1. Disadvantaged Persons Affected by Migration

3.2. Awareness and Use of Practical Resources

3.3. Rank Shift Analysis and Non-Responders

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications for Policy and Research

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| What Are the Populations of Interest in Order to Develop Responsive, Socially Cohesive and Responsive Health Systems in a Time of Migration? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroups of Migrants (at Risk for Health Inequities) | The “Excluded” (Political and System Exclusion) | Competition from Other Non-Migrant Populations | Outlier: Intersectionality (Piecing It All Together) |

| Undocumented families Rural workers New migrants in urban slums Unaccompanied minors Migrant with low literacy [Migrant] pregnant women People in detention centers Forced migrants, asylum seekers Trafficked women Members of sexual minorities Those subject to xenophobia Survivors of torture Low wage migrants in Arab countries New Spanish speaking rural migrant workers Vulnerable Refugees, immigrants and temporary foreign workers with specific needs | The broken is systematic and does not lie in the population itself Rather sets of social, political, and discriminatory and generation factors, place migrants at risk Vulnerabilities often due to structural marginalization Issues generating a gap between this population pocket and the social and healthcare services Discrimination with respect to access to employment, low wages, and additional barriers for immigrant women | Refugees receive support while other disadvantaged communities don’t—primary and secondary populations Disadvantaged populations may include migrants or receiving country communities Communities receiving the migrants share the burden The secondary population represents vulnerable individuals living within a jurisdiction, whose health and wellbeing is affected by patterns of migration in their community | I prefer to speak of diversity where possible, and this emphasizes the status between immigrant status, ethnicity, and inequity (an intersectional approach). |

| Tools/Resources | (%) of Experts Who Have Used the Tools/Resources | |

|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | |

| 1. International Organization for Migration Publications (n = 30) | 18 | (60.0) |

| 2. Community Engagement Guidelines (n = 26) | 15 | (57.7) |

| 3. Migrant Health Expert Opinion guidelines (n = 36) | 15 | (53.6) |

| 4. Community Health Mediators (n = 28) | 13 | (46.4) |

| 5. WHO Essential Drug Program (n = 28) | 13 | (44.8) |

| 6. Evidence Based Migrant Health Guidelines (n = 28) | 9 | (32.2) |

| 7. Health (Equity) Impact Assessment (n = 27) | 9 | (33.3) |

| 8. Machine translation for medical care (n = 28) | 5 | (17.9) |

| 9. Migration Integration Policy Index (MIPEX) (n = 26) | 3 | (11.5) |

| Tools/Resources | (%) of Experts Aware of the Tools/Resources | |

|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | |

| 1. International Organization for Migration Publications (n = 30) | 26 | (86.7) |

| 2. Health (Equity) Impact Assessment (n = 29) | 22 | (79.3) |

| 3. WHO Essential Drug Program (n = 28) | 21 | (75.0) |

| 4. Evidence Based Migrant Health Guidelines (n = 29) | 19 | (69.0) |

| 5. Community Health Mediators (n = 29) | 18 | (62.1) |

| 6. Migrant Health Expert Opinion guidelines (n = 30) | 18 | (60.0) |

| 7. Machine translation for medical care (n = 29) | 15 | (51.7) |

| 8. Community Engagement Guidelines (n = 29) | 15 | (51.7) |

| 9. Migration Integration Policy Index (MIPEX) (n = 30) | 11 | (36.7) |

| The Main Concerns | % of Experts Agreement 1 |

|---|---|

| (n = 32) | (%) |

| Describing disadvantaged populations | (83.9) |

| Building a responsive health system | (87.1) |

| Defining “scope of migrant related initiatives” | (100.0) |

| Data identification and analysis | (77.4) |

| Engaging migrant communities | (83.9) |

| Implementing evidence-informed policy | (89.6) |

References

- World Migration Report 2015. Available online: https://www.iom.int/world-migration-report-2015 (accessed on 10 August 2016).

- Ingleby, D. The Refugee Crisis: A Challenge to Health Systems. Lecture Given at German Academy of Sciences, Berlin. 2 December 2015. Available online: http://bit.ly/2jBvP0o (accessed on 20 May 2016).

- IOM. Summary Report on the MIPEX Health Strand and Country Reports. Available online: http://bit.ly/2g0GlRd (accessed on 20 May 2016).

- Pottie, K.; Greenaway, C.; Hassan, G.; Hui, C.; Kirmayer, L.J. Caring for a newly arrived Syrian refugee family. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2016, 188, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Chammay, R. Reforming mental health in Lebanon amid refugee crises. Bull. World Health Organ. 2016, 94, 564–566. [Google Scholar]

- Pace, P. The right to health of migrants in Europe. In Migration and Health in the European Union; McGraw Hill: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Miramontes, L.; Pottie, K.; Jandu, M.B.; Welch, V.; Miller, K.; James, M.; Roberts, J.H. Including migrant populations in health impact assessments. Bull. World Health Organ. 2015, 93, 888–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingleby, D. International Organization for Migration, 2009. Available online: http://bit.ly/2jJPDmn (accessed on 20 May 2016).

- Ingleby, D. Getting multicultural health care off the ground: Britain and The Netherlands compared. Int. J. Migr. Health Soc. Care 2006, 2, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. SAGE Vaccination in Acute Humanitarian Emergencies: A Framework for Decision Making; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- Task Force on Health Systems Research. Informed choices for attaining the Millennium Development Goals: Towards an international cooperative agenda for health-systems research. Lancet 2004, 364, 997–1003. [Google Scholar]

- Immigrant Supplement for the Ontario MOHLTC Heath Equity Impact Assessment Program. Available online: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/heia/tool.aspx (accessed on 20 January 2017).

- Hankivsky, O. Women’s health, men’s health, and gender and health: Implications of intersectionality. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 1712–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pottie, K.; Mayhew, A.; Morton, R.; Greenaway, C.; Akl, E.A.; Rahman, P.; Menjivar-Ponce, L.; Zenner, D.; Pareek, M. Prevention and assessment of infectious diseases among children and adult refugees and migrants to the EU/EA: A protocol for a systematic review for public health and health services. BMJ 2016. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Pottie, K.; Gruner, D. Health equity: Evidence-based guidelines, e-learning and physician advocacy for migrant populations in Canada. In Globalisation, Migration and Health: Challenges and Opportunities; World Scientific: London, UK, 2016; pp. 329–343. [Google Scholar]

- Povall, S.L.; Haigh, F.A.; Abrahams, D.; Scott-Samuel, A. Health equity impact assessment. Health Promot. Int. 2014, 29, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakarishvili, G.; Lansang, M.A.; Mitta, V.; Bornemisza, O.; Blakley, M.; Kley, N.; Burgess, C.; Atun, R. Health systems strengthening: A common classification and framework for investment analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2011, 26, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornemisza, O.; Bridge, J.; Olszak-Olszewski, M.; Sakvarelidze, G.; Lazarus, J. Health aid governance in fragile states: The Global Fund experience. Glob. Health Gov. 2010, 4, 2–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bornemisza, O.; Ranson, M.K.; Poletti, T.M.; Sondorp, E. Promoting health equity in conflict-affected fragile states. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omariba, D.W.R.; Ng, E. Immigration, generation and self-rated health in Canada: On the role of health literacy. Can. J. Public Heal. Can. Santee Publique 2011, 102, 281–285. [Google Scholar]

- Migrant Health | Cochrane. Available online: http://methods.cochrane.org/equity/migrant-health (accessed on 8 January 2017).

- Lavis, J.; Davies, H.; Oxman, A.; Denis, J.-L.; Golden-Biddle, K.; Ferlie, E. Towards systematic reviews that inform health care management and policy-making. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2005, 10, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IOM & Asia-Europe Foundation (ASEF). Report of an Inter-Regional Roundtable Discussion “Addressing Health Vulnerabilities of Migrants in Large Migration Flows”; IOM & Asia-Europe Foundation (ASEF): Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Giannoi, M.; Franzini, L.; Masiero, G. Migrant integration policies and health inequalities in Europe. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 463. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤30 | 2 | (5.6) |

| 31–40 | 6 | (16.7) |

| 41–50 | 10 | (27.8) |

| 51–60 | 12 | (33.3) |

| >60 | 6 | (16.7) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 20 | (48.8) |

| Female | 21 | (51.2) |

| Country of current practice | ||

| Australia | 6 | (14.6) |

| Belgium | 1 | (2.4) |

| Canada | 9 | (22.0) |

| China | 1 | (2.4) |

| Denmark | 1 | (2.4) |

| Germany | 1 | (2.4) |

| Greece | 1 | (2.4) |

| Italy | 1 | (2.4) |

| Lebanon | 3 | (7.3) |

| Malaysia | 1 | (2.4) |

| The Netherlands | 4 | (9.8) |

| Spain | 1 | (2.4) |

| Sweden | 3 | (7.3) |

| United States of America | 8 | (19.5) |

| Mother tongue | ||

| English | 17 | (47.2) |

| Other | 19 | (52.7) |

| Current professional role | ||

| Primary health care practitioner | 11 | (26.8) |

| Public health/surveillance professional | 6 | (14.6) |

| Migration policy developer | 2 | (4.8) |

| Migration health researcher | 14 | (34.2) |

| Health impact assessment developer | 1 | (2.4) |

| Other | 6 | (14.6) |

| Length of time researching/practicing/working with migrants | ||

| ≤5 years | 5 | (15.6) |

| 6–10 years | 11 | (34.4) |

| 11–15 years | 6 | (18.6) |

| >16 years | 10 | (31.3) |

| Length of time in migrant research/policy | ||

| ≤5 years | 11 | (34.4) |

| 6–10 years | 10 | (31.3) |

| 11–15 years | 6 | (18.8) |

| >16 years | 5 | (15.6) |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pottie, K.; Hui, C.; Rahman, P.; Ingleby, D.; Akl, E.A.; Russell, G.; Ling, L.; Wickramage, K.; Mosca, D.; Brindis, C.D. Building Responsive Health Systems to Help Communities Affected by Migration: An International Delphi Consensus. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14020144

Pottie K, Hui C, Rahman P, Ingleby D, Akl EA, Russell G, Ling L, Wickramage K, Mosca D, Brindis CD. Building Responsive Health Systems to Help Communities Affected by Migration: An International Delphi Consensus. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017; 14(2):144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14020144

Chicago/Turabian StylePottie, Kevin, Charles Hui, Prinon Rahman, David Ingleby, Elie A. Akl, Grant Russell, Li Ling, Kolitha Wickramage, Davide Mosca, and Claire D. Brindis. 2017. "Building Responsive Health Systems to Help Communities Affected by Migration: An International Delphi Consensus" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14, no. 2: 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14020144

APA StylePottie, K., Hui, C., Rahman, P., Ingleby, D., Akl, E. A., Russell, G., Ling, L., Wickramage, K., Mosca, D., & Brindis, C. D. (2017). Building Responsive Health Systems to Help Communities Affected by Migration: An International Delphi Consensus. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(2), 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14020144