2. Data and Methods

This article draws primarily on the findings of the Faith and Organizations Project, a national research/practice initiative started in 2001 by faith community and FBO leaders from several faiths in order to provide evidence-based tools and examples to FBOs, faith communities, policymakers and researchers.

1 The overall plan for the project involved examining four aspects of the relationship among faith communities, FBOs, government and other stakeholders: (1) the relationship between faith communities and the FBOs they either founded or currently sponsor; (2) the ways that religious culture and values play out in the structure and programming of FBOs; (3) the role of FBOs in their sectors (interactions with government, other funders, other organizations providing similar services); and (4) relationships with people served by the organization. The pilot study (2004–2006) [

23] provided preliminary data on all four topic areas while the Maintaining Vital Connections Between Faith Communities and their Organizations Study (2008–2010) [

24], funded by Lilly Endowment Inc.) focused primarily on the first two questions.

The project included three types of comparisons: comparisons across religions and denominations, comparisons among organizations providing different kinds of services and observations regarding the role of organization size, age, funding sources and other organizational characteristics. The project design includes comparisons among Catholics, Mainline Protestants, Jews, Muslims, Evangelicals, Peace churches (Quakers, Mennonite, Brethren) and African American Christians. Our second study also included several organizations sponsored by interfaiths.

The project has consistently compared a wide range of agencies in four broad service areas: social services (from large multi-service organizations, like Catholic Charities, Jewish agencies and Lutheran Children and Family Services (LCFS) to local FBOs providing housing for people with disabilities or other social services, to congregation-sponsored blessing rooms), healthcare and senior services (hospital systems, retirement communities, clinics, congregation sponsored seniors programs), education (K-12 religious schools) and community development projects (community development corporations, emergency services, youth enrichment).

2 With the exception of one Evangelical congregation’s emergency services ministry, all organizations were either 501c3 nonprofits or congregation-sponsored entities with a separate bank account and advisory committee. They ranged in size and age from multi-million dollar organizations several hundred years old with multiple locations to congregation-sponsored ministries in existence for less than five years. We purposely did not include any congregation-based ministries run exclusively as projects of a pastor or committee.

The Maintaining Vital Connections Study [

24] examined the relationship between 81 faith-based organizations located in the Northeast (from Philadelphia to Northern Virginia), Midwest (Ohio and Chicago) and South (South Carolina) and their sponsoring faith communities. An earlier pilot study of 11 faith-based organizations was conducted between 2004 and 2006 in Philadelphia and the greater Washington Metropolitan area.

3 The project compared strategies used by the various denominations for guiding, supporting and maintaining connections with their nonprofit organizations. Depending on the religion or denomination, these guidance and support activities were carried out primarily by congregations, by higher level judicatories, like Jewish Federations, a Catholic diocese or a Quaker Yearly Meeting, by intermediary organizations, such as Friends Services for the Aging or a Catholic healthcare system, or by a combination of any of these institutions.

We focused on pairs of institutions, for example a congregation and the school that it had founded. In some cases, a single faith community founded several organizations. For example, a large, several hundred-year-old Quaker Meeting had founded a retirement community, a senior services organization and a school and was also a key member of an interfaith community development corporation. We also included several interfaith organizations that were sponsored by as many as 30 individual congregations. “Interfaith” in this context usually meant sponsorship from a variety of Mainline Protestant denominations, sometimes with one Catholic parish or Quaker Meeting added to the mix. However, several interfaith organizations had expanded to include Jews, Muslims and secular community groups as supporters, as well. In most cases, the practical theology and primary support system of the interfaiths came from a small number of particularly active Mainline Protestant congregations or a combination of Mainline Protestants and Catholics, so in these organizations, we concentrated on connections to the most active congregations.

Jewish and Catholic communities, through various umbrella institutions, such as the Federation, a religious order or a diocese, were responsible for a full range of organizations, and we chose two or three institutions under each of those denominational umbrellas for intensive study. Federations are regional centralized fundraising, planning and support institutions for Jewish non-profits providing a wide array of services [

27,

28]. To understand the nature of these relationships, we focused on how they were enacted at several different levels. For example, our research on order-sponsored Catholic hospitals included research on the regional office of one order, the national health system that oversaw all of its hospitals plus those of several other orders and a single hospital located under this umbrella in Baltimore. Jewish Federation research included a local Federation and several of its organizations, also looking at links to local synagogues and national umbrella organizations. The study looked at the faith community’s understanding of its overall sponsorship role and the types of organizations it considered to be affiliated with it, as well as at the specific relationships between each faith community and selected organizations. Both studies combine several qualitative methods:

- ■

Overview history of each faith community’s support and guidance of its organizations and ministries, as well as a history of the relationship between the faith community and specific selected organizations: Histories were developed using existing histories of the organization or faith community, a review of documents related to stewardship (e.g., archived minutes of meetings, religious statements, statements of justice and charity activities or other documents relating to the guidance of the organizations) and interviews with people knowledgeable about the history of the faith community or the organization.

- ■

In-depth interviews with current and former key individuals from both the faith communities and organizations regarding present-day relationships and organizational patterns.

- ■

Participant observation in faith community oversight activities and selected organization events related to the relationship with the faith community: Project researchers attended numerous faith community and organization activities and sat in on meetings relevant to maintaining connections to the organization. These activities and meetings varied by faith tradition and included faith community committee meetings, presentations by selected organizations to the faith community, organization board meetings, annual meetings and events for the larger community. Other participant observation opportunities involved infrequent activities (e.g., an annual presentation at a Yearly Meeting or Synod conference, an annual Christmas party or an organization festival honoring volunteers), quarterly committee meetings or monthly board meetings. In addition to observing meetings and events, our staff participated in weatherization days, summer arts programs and other direct service volunteer activities where relevant. While observing, researchers also talked with participants about how they had learned of the organization or event, their thoughts on the organization and key faith-related reasons for being involved with the organization.

- ■

Analysis of recent and ongoing written materials produced by the faith community and selected organizations: these included board and committee minutes, outreach and recruitment materials, theological materials related to charity and justice activities and other similar documents.

- ■

Relationship self-assessment questionnaires: One of the products of the study was a combination qualitative and quantitative self-assessment tool for both faith communities and organizations to use. Toward the end of the study, this self-assessment instrument was tested in both selected organizations in the in-depth study and additional FBOs and faith communities in the South, Midwest and East Coast.

These various data were drawn together and used to: (1) develop comprehensive pictures of each organization/faith community relationship; and (2) provide comparative material for general analysis. We used several standard ethnographic analysis techniques to understand our findings [

29], including creating keyword-based analysis runs using the DTsearch program (

http://dtsearch.com/).

In addition to Faith and Organizations Project research, I draw on several of my earlier research/practice experiences. Between 1981 and 1988, multi-method ethnographic dissertation research on refugee resettlement for Soviet Jews and Poles in Philadelphia, focusing on refugees interactions with Catholic, Jewish, Mainline Protestant, Lutheran and one secular non-profit responsible for resettlement, as well as interactions with government and the faith/ethnic communities in which they were settled [

26,

30]. Practical experience running both a faith-based youth development program and serving as an administrator in a secular organization offering welfare to work and training in Philadelphia between 1992 and 1997 was combined with twelve studies conducted between 1992 and 2002 in Philadelphia, Kenosha and Milwaukee Wisconsin in order to analyze social welfare supports for families in Pennsylvania and Wisconsin [

7]. The welfare and poverty research examined community responses to the needs of various populations, including multi-method ethnography of both faith and secular communities’ interaction with government as well as non-profit and FBO activity. Finally, I briefly draw on experience working with the federal government as an AAAS fellow at the National Cancer Institute from 2003–2005. My primary project involved creating a model for federal government agencies and national non-profits to better connect with local faith communities, FBOs and secular community entities in order to improve healthcare too hard to reach populations.

3. The Rhetoric and Reality of Government Relationships to Faith Communities and FBOs

While proponents of charitable choice provisions in the 1996 welfare reform law

4 and the Bush-era faith-based initiative claim a renewed interest in faith communities providing supports in partnership with government, historians of social services in the U.S. note that faith communities and FBOs provided the bulk of social services in the U.S., often with government funding, from before the United States was formed [

31,

32,

33,

34]. In fact, faith communities were the primary support for the needy before passage of the Roosevelt New Deal programs in 1935 [

3,

31,

32]. The government’s role as the primary provider of income supports lasted only from the New Deal until passage of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act (PRWOA) (often known as Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF)) in 1996. Emergency services,

5 training, medical care, support for at-risk children and many other social programs always included faith communities and their organizations as significant providers [

3,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Wineburg et al. [

3] date the devolution of services to faith-based and secular non-profits to the Reagan era, with significant increases in contracting out services previously offered directly by government following welfare reform in 1996. Other scholars date the proliferation of non-profits in the U.S., many funded through government contracts,to the 1960s [

35,

36].

The same pattern is true for healthcare and education. While most medical practitioners have always been for-profit, hospitals started out as community or religious institutions [

37]. Government gradually began to play an increasing role in funding healthcare for the elderly, low income and those with special needs only after the passage of Medicaid and Medicare in 1965. Educational systems only gradually came under state control, with faith communities maintaining separate systems to this day.

While faith community involvement in social services, healthcare, senior services, emergency services and education has a strong legacy in the United States, religious involvement in service provision had different rationales for Jews, Catholics and Protestants. As Hall [

33,

38] documents, Protestants dominated U.S. culture from the colonial era on in most communities, deliberately secularizing their non-profits by the end of the 19th century in an effort to maintain moral authority. Modern social work also evolved from two fundamentally religious movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Charitable Organization Societies and the social gospel movements [

31,

34]. The Jewish and Catholic systems, on the other hand, developed originally as alternative venues for their co-religionists to obtain services and education outside of the predominantly Protestant mainstream institutions [

27,

39,

40,

41]. However, by the 20th century, Catholic and Jewish institutions served everyone, and the Catholic school system had become an important alternative to public education for many non-Catholics in large urban school systems.

The legacy of this long history of religious involvement in social services, healthcare and education is evident in the significant presence of organizations founded by faith communities in U.S. social services. Ammerman ([

20], p. 179) notes that Lutheran Social Services, Catholic Charities, the Jewish social service network and the Salvation Army comprise some of the largest providers of social services in the U.S. Catholics run the largest health systems in this country, as well as the largest independent school system [

40,

42,

43]. Wineburg et al. ([

3], p. 25) report that by 1981, the U.S. census reported that 47 percent of private U.S. social service expenditures went to FBOs. Established FBOs have also continued to receive the bulk of government funding. Scholars report that most funding for faith-based organizations goes to FBOs with a long history of government funding [

6,

14], and a U.S federal government report noted that 93 percent of the FBOs receiving funds from Housing and Urban Development and that 80 percent of FBOs funded by Health and Human Services had received government funding before [

44].

3.1. Charitable Choice, FBNI and the Role of Faith-Based Organizations

A full discussion of the Clinton and Bush faith-based initiatives are beyond the scope of this paper. Readers interested in policy history will find other articles in this volume that discuss the Bush initiative in detail. While the Clinton Charitable Choice legislation and Bush Faith-Based and Neighborhood Initiative did not initiate faith-based involvement in the U.S. social welfare system or partnerships between government and faith communities, it did shift the focus and goals of involving faith communities in government-sponsored service provision. Prior to these two initiatives, government contracts stipulated that religiously-based non-profits could not use religious elements in government funded programs. This meant that, while agencies like Catholic Social Services and Jewish Employment and Vocational Services embedded their religious values in their social services, they could use no outward signs of religion or religious elements in their programming or facilities. Organizations providing services through congregations, like the congregations that resettled refugees for Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Services and Church World Service were enjoined to not proselytize to the families they hosted [

26,

30].

My research in the 1980s revealed that agencies managed this separation of church and state through their connections to their wider faith communities. For example, Catholic Poles resettled by Catholic Social Services were usually resettled in Polish Catholic neighborhoods and would generally receive a visit from the priest from the nearest parish to invite them to attend church and tell them about the school within a week after arrival. While religion was not mentioned at Catholic Social Services, I suspect the list of incoming refugees was quietly shared with the parishes. Likewise, Jewish agencies resettled Soviet Jews in largely Jewish neighborhoods, offering low cost or free memberships to the Jewish Community Center, Jewish child care centers, seniors programs and other more openly Jewish services available in that community. Synagogues were encouraged to offer low cost memberships to Soviet Jews by the local Federation [

26,

30].

Many scholars and policymakers alike presumed that organizations offering secularized services would become more secular over time [

45]. Starting with a Reagan-era speech, these large, multi-service non-profits were equated with the uncaring, bureaucratic services of government ([

3], p. 23). The faith-based initiative was designed to encourage congregations and smaller, more openly faith-based FBOs to compete for government contracts. Proponents of the new FBNI claimed that established FBOs like Catholic Charities, Jewish Children and Family Services and Episcopal Community Services were secular because they “did not preach or disseminate religious doctrines, hired professionally trained staff who were not necessarily from their faith tradition, did not celebrate religious holidays with clients, and mirrored their secular counterparts” ([

46], p. 6).

In contrast, the ideal FBO would be grounded in a congregation, providing “holistic”, caring services through volunteers and staff hired from the faith community, rely on free or less expensive resources from that faith community and transform the individual receiving services through religiously-based programming. While critics argued for separation of church and state through a variety of mechanisms, both scholars and policymakers attempted to identify the faith base in organizations, so that they could determine if openly religious providers were “better” than secular nonprofits or those that did not use religious elements in their programming. Numerous scholars and a policy committee created a series of scales, most relying on outward signs of religiosity, to identify the level of faith in an organization [

15,

45,

47,

48,

49]. Generally, the scales included a number of gradations varying from secular to faith integrated, with the faith-integrated programs using prayer and other religious elements in their programming and generally suffusing religion throughout their programs. While each of these scales were careful to note that different organizations used religion in varying ways, the general impression they offered was that more visibly religious organizations were more faith based than others.

Scholars attempted to develop evaluation tools to measure the role of faith in service provision, one step in determining if faith-based or secular programs provided “better” services (for example, [

50]). Many scholars noted that faith was often linked in the policy rhetoric with transformation, with proponents of the faith-based initiative assuming that FBOs would engender transformation in the individual through the faith elements.

6 Measures of religious program effects often focused on levels of faith using one of the typologies identified above (for example, [

51]), comparing organizations grouped by the type of religiosity on standard program outcomes, such as number and characteristics of job placements [

14,

16,

52,

53]. Most of the empirical studies comparing FBOs with various levels of faith to each other and secular organizations found evaluations difficult to do, faith hard to measure and complex results [

14,

16,

53,

54].

As the policy rhetoric encouraged openly religious organizations and congregations to become involved in government-funded service provision, established FBOs worried that they would lose contracts as funds were targeted toward congregationally-based, supposedly holistic, small FBOs [

6]. The scholarly literature documented this focus on congregation-sponsored programs and smaller FBOs through such initiatives as government outreach through faith-based liaisons and other mechanisms [

18,

55] and technical assistance to new faith-based and community organizations through the Compassion Capital Fund and similar initiatives [

6,

14]. Larger, established FBOs responded by clarifying the religious roots of their organizations [

41,

56,

57].

Analysis of the focus on congregations, the descriptions of ideal FBOs and transformation suggest that these visions of the role of faith-based organizations in social services reflect Protestant and Evangelical approaches to social service. As discussed in detail elsewhere [

58,

59], our research found that these two denominations organize their social support activities through congregations or networks of people with a shared faith vision, often relying on congregations or networks for resources, volunteers and staff. Evangelicals are most likely to infuse faith through all elements of an FBO. Images of transformation could imply the impact of profound instances of faith found in most religious traditions, but it most resembles the process of being “born again” in Evangelical parlance. African American congregations are most likely to develop complex, government-funded service initiatives through a congregation [

5,

60]. African American Christians can follow either Mainline Protestant or Evangelical faith approaches, but FBOs and congregational projects tend to be clearly pastor led and closely tied to the congregation [

60].

While the reliance on Evangelical and Protestant models is unsurprising given their predominance in U.S. culture and politics at the time, as well as the religious background of President Bush, they do privilege one model of organizing faith community service provision over others. Emphasis on Evangelical and Protestant models at the state level reflects the fact that the majority of the faith-based liaisons came from these traditions and that their activities reflected their religious approach and networks. Sager ([

55], p. 106) notes that 17 of the 30 state faith-based liaisons she interviewed were conservative or liberal Protestant, five were Catholics and only two came from a non-Christian background. As discussed in more detail below, Protestant and Evangelical models are not shared by all religious traditions, particularly the Jewish and Catholic organizations that provide a significant proportion of services in this country. Policy suggestions will focus on expanding the vision of what constitutes a faith-based organization, the nature of the faith community and ways that faith communities relate to FBOs to include the range of religious traditions in the United States.

The scholarly consensus on the Bush faith-based initiative was that it brought in few new contractors, and many of the smaller or newer organizations interested in the faith-based initiative had trouble competing successfully for contracts [

14,

16]. Research on congregations showed that while most congregations participate in some form of social outreach, these programs are usually low intensity initiatives and that most congregations would prefer to partner with FBOs or secular non-profits to provide more complex services [

2,

5]. Research on the impact of the faith-based initiative showed that while more congregations expressed interest in social welfare, only African American congregations and those already providing complex services likely to be funded by government sought government funds [

1,

9]. This clearly suggests that strengthening non-financial partnerships with faith communities was an appropriate direction for the Obama administration Faith-Based and Neighborhood Initiative.

3.2. Government Partnerships with Faith Communities and FBOs

How does government interact with FBOs and faith communities now? Both the literature and research experience suggest four types of interactions; first, government contracts with FBOs, faith community intermediaries or congregations to provide specific services. Examples of FBO/government contracts would include contracts with Catholic Charities to provide GED or foster care services, a subcontract between a quasi-governmental agency like a workforce development board and a faith-based training provider or city funding to an interfaith Community Development Corporation (CDC) using federal Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) monies to develop a low to moderate income housing project. Intermediary contracts also involve an incorporated entity, for example a Jewish Federation contract for refugee resettlement, which is used to fund programs by several Federation agencies to serve specific needs of refugees in that community. Congregation contracts also involve either a congregation or a congregation-affiliated FBO, like Head Start contracts with an African American church’s non-profit entity or direct funding to a congregation to run a welfare to work program.

In each case, competitive contracts or grants connect a government entity with a single provider. The faith community supporting that incorporated agency is generally not part of the negotiation or implementation of the contract, although the contract may include an in-kind match of space, volunteers or other resources provided by the faith community. When matches are involved, the non-profit or congregation receiving the contracts works with its faith community to obtain matching resources; government is usually not a part of this interaction.

The second form of interaction involves government funding through some form of voucher, such as Medicare or Medicaid insurance payments to a hospital or clinic, public school vouchers to religious schools or a Workforce Investment grant

7 given to an individual to obtain training from a program of his or her choice. In each case, FBOs receiving payment through a voucher are subject to government regulation related to those vouchers. For example, Catholic schools participating in Milwaukee’s school choice program had to offer an alternative to religious instruction to students attending through the voucher program. Schools, hospitals, training programs and a variety of other entities are subject to various forms of government regulation regardless of whether or not they receive funding from government either directly or indirectly.

Government funding for FBOs in any form raises concerns regarding the impact of government funding on FBO or congregation autonomy. Monsma ([

16], pp. 20–24) describes a statist approach to government/non-profit relations, which envisions government as the appropriate funder for services, but sees the agency receiving funds as responsible for providing services according to government guidelines. As such, the non-profit becomes an arm of government, leading to conformity among programs, lack of autonomy and loss of individuality [

62,

63,

64]. Research shows that both congregations and FBOs report that fear of government intervention in religious elements of programs or organizations is a major reason not to seek government funding [

9,

65]. Despite this concern, some researchers show that FBOs and other non-profits are able to both conform to government dictates and maintain unique program elements that reflect their mission and religious traditions [

7,

24,

36]. Research suggests that mixed sources of income enable freedom to add program elements beyond government dictates [

16] and that even small amounts of funding from a faith community can powerfully shape program direction [

23,

24].

The third form of government/faith community interaction involves government disseminating information through FBOs or faith communities. Examples include providing referral data on WIC, food stamps

8 or welfare through faith-based homeless shelters. Another common strategy involves government or government funded programs to improve health and welfare, such as a National Cancer Institute/American Cancer Society (ACS) initiative to get African American churches to develop programs to promote fruit and vegetable consumption by their members. The program used government-/ACS-created materials and program guides disseminated through a combination of social marketing and contacts with national-level faith community leaders. Other examples include NIH-funded efforts to offer programs in churches to prevent diabetes or promote healthy behaviors [

66,

67]. Federal and local government attempting to coordinate faith-based responses to natural disasters, such as Katrina or Haiti, through information dissemination is another example.

In each case, government agencies either use known contacts or media to provide information through faith communities, presuming that they will have greater reach than government itself. Particularly with efforts to promote health or social programs, contacts are often with congregations or higher level adjudicators on the presumption that these entities are most able to reach target populations. Occasionally, the same strategy is used to recruit volunteers for mentoring, foster parents or other initiatives. However, these efforts are more likely to come from an FBO with a government contract than government directly.

The final form of interaction involves inviting faith community or FBO representatives to participate in government sponsored coalitions. The various task forces sponsored by the Obama administration that made recommendations related to this administrations Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships is one example. All levels of government use task forces or coalitions for various initiatives, and some government-sponsored programs require community participation. The nature of these coalitions varies greatly depending on the level of government and collaborative goals.

In most cases, all four forms of collaboration involve contracts between government and an entity presumed to represent a larger faith community. Contracts and vouchers are the exception, as the relationship is usually exclusively between government and the FBO or the faith community entity receiving funding. Particularly with information dissemination efforts and some coalitions, government outreach to the faith community or FBO is expected to reach into a broader community. However, these initiatives may not understand the unique attributes of the faith community that shape appropriate approaches to collaboration and ways that faith communities and FBOs may respond to government goals. True partnership involves better understanding the nature of the three-way relationship among faith communities, FBOs and government. I now turn to the discussion of the key findings from the Faith and Organizations project that could enhance partnerships for government, faith communities and FBOs.

4. Religious Social Support Systems and Their Potential Relationships with Government

This brief description of government’s current interactions with faith communities and FBOs suggests that government forms relationships with individual organizations for tangible purposes like providing a service or disseminating information on healthy behaviors. However, these organizations come out of multiple communities and interact with several constituencies.

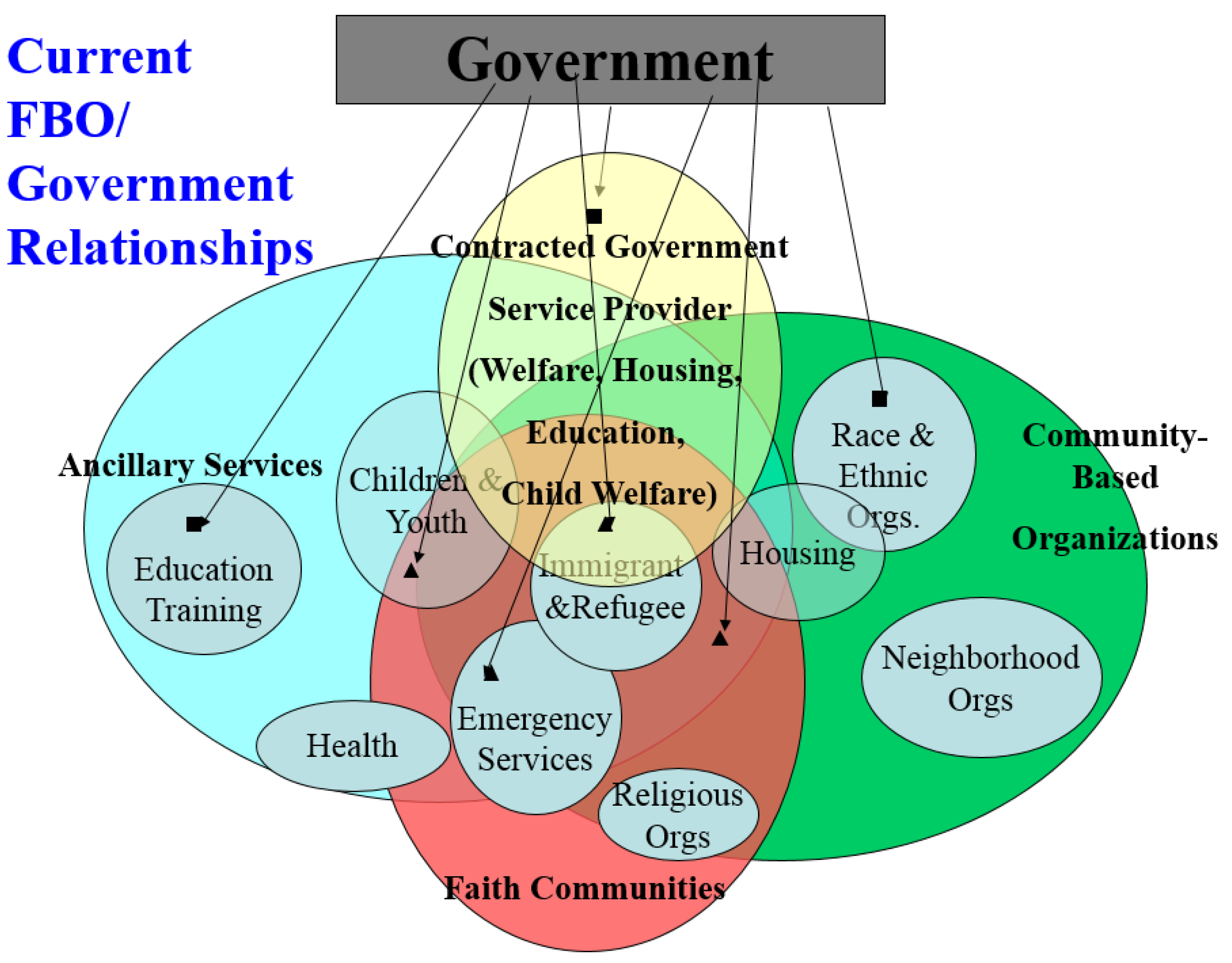

Figure 1 comes initially out of my work on social welfare support systems [

7], illustrating local systems for service provision. Each of the large circles represents a community of citizens and institutions that creates non-profit, for-profit and faith-based organizations to provide services. The large circles, community-based, faith-based, government-contracted and ancillary services, indicates networks of individuals and organizations that come out of a specific social, religious or geographic community. The faith community circle would include the institutions and members of all of the denominations and religions in a particular locality, consisting of smaller circles for Jews, Catholics, Muslims, Mainline Protestants, etc. These smaller networks may be linked to each other through denominational conferences and to other religions or denominations through interfaiths or more informal inter-religious collaboration. The large community-based circle includes both geographic neighborhoods and communities of identity (race, ethnic, immigrant/refugee, sexual orientation, etc.). As with the faith community circle, it actually would contain many sub-circles whose members may or may not work with each other. The contracted government and ancillary services circles represent citizens and organizations that come together to address a specific need, such as educating children, providing healthcare or working with government to address poverty.

The smaller circles represent networks of organizations providing a specific service, like emergency services or housing, or providing venues for social activities, support and advocacy for people from a particular racial, ethnic, immigrant or religious group. As these small circles indicate, the organizations and people associated with them tend to know each other either as competitors or collaborators, but may not have ongoing relationships with organizations offering another kind of service. This siloing of services is typical in the U.S. and even occurs sometimes in multi-service organizations where the staff involved in childcare may not interact with people in their own agency offering housing services, but would be connected to staff at other organizations providing child care in a variety of information sharing and coalition activities ([

7], pp. 239–62). Both the Faith and Organizations Project research [

24] and other scholars have noted that agencies tend to work as part of networks, with faith-based organizations more often collaborating with other FBOs or faith communities [

6,

54].

While these networks focus on a specific need, their membership overlaps with faith community- and community-based networks. For instance, a retired lay leader in a Quaker Meeting worked as a lawyer specializing in housing for the poor and elderly. As a volunteer, he sat on the board of both faith-based and secular housing organizations, as well as serving as an active member of the local council for the elderly. Because of his known expertise in these areas, he provided advice to agencies developing housing for low income people and the elderly through government contracts and has served on local government advisory committees on these topics. Over time, he has developed trust-based relationships with many individuals and organizations in his faith community, as well as the work and volunteer arenas in which he is involved. As such, he has connections in faith-based, ancillary services and government-contracted circles. Those connections provide him with access to resources and information that he could share within any of these communities or with government.

Trust-based connections that can lead to resources are called social capital [

68,

69]. Both organizations and individuals develop social capital that they use to garner resources, advice and support [

7,

70]. While all individuals and organizations develop bonding social capital among people or organizations like themselves, some research and policy discussion suggest that the most successful develop connections outside of their core communities or bridging social capital [

71]. Partnership with government also involves local organizations and communities fostering linking social capital [

72] or trust-based relationships with institutions with unequal power relations, such as government and an agency receiving a government contract. My work suggests that bridging, bonding and linking social capital are equally important to meet goals [

7,

70].

While individuals and organizations in each of these circles may have access to resources through their connections, the nature of those connections and the unspoken rules and behaviors necessary to access them come out of the culture of that particular community. People and organizations that have access to community resources have also developed cultural capital or the learned behaviors or symbols of identity that indicate membership in a group. Faith and Organizations Project research found that cultural capital, in the form of shared religious values and visible practices connected with that faith, was essential for FBOs to garner support from their faith communities. Faith communities expected their FBOs to reflect their practical theology: the formal and informal mechanisms a faith community uses to enact its theological teachings through its religious culture and structures. Faith communities saw their role in supporting or guiding FBOs they sponsored not simply as providing board members, funding, volunteers or other resources, but offering guidance and oversight to ensure that the organization reflected its religious base. FBOs and faith communities understood themselves as stewards of their FBOs, defining stewardship as overall administration and guidance for non-profits by the founding or supporting faith community [

73]. Study results reveal that support structures for religious-based non-profit activities come from the practical theology of their founding religion, leading to the development of systems of stewardship based on religious values and practices. Further, communities support organizations that reflect their practical theology through publicity for the organization and tangible supports, like donations, volunteers and ongoing partnerships. FBOs that stray from the practical theology of their faith community become targets for community concern, facing reduced donations, trouble finding board members from the faith community and other indicators of diminishing support.

These findings have significant implications for government partnerships with FBOs. As illustrated in figure one, government may contract with an FBO or secular agency to offer a specific service. The arrows to squares represent contracts or dissemination relationships with secular non-profits while the arrows to triangles represent government collaborations with FBOs. The point of this chart is that, while government may understand that these individual organizations come out of communities, the relationship most often focuses on the concrete goals of that specific activity. As with the statist paradigm for government/FBO relations, government focuses on the agency’s ability to successfully deliver a particular program as stated in an RFP or program outline created by government; for example, placing 50 percent of trainees in a welfare to work program in jobs offering $6.00 per hour, with at least half of the jobs offering health insurance; or a church may be asked to present a nutrition program promoting eating nine servings of fruit and vegetables a day to 50 members, enrolling 25 in a pledge program to meet specific nutritional goals for 90 days. In each case, the goals are determined by government in a classic top down bureaucratic fashion [

74]. If an agency uses additional resources or strategies from their faith tradition to meet the stated outcomes, so much the better, but the point is to meet program outcomes and account for those activities, not offer faith-based interventions.

The Bush-era faith-based initiatives emphasis on congregations and small FBOs presumed that working directly with a congregation or an FBO strongly tied to a faith community would automatically provide services that would have extra resources and new approaches from that faith community. However, the goals were government goals. Rather than develop relationships both with an FBO and the faith community that supported it, contracts were with the FBO only. Even though the faith community could be expected to provide resources like space, volunteers or in-kind contributions, they were generally not part of the contract negotiation or party to the contract. While both Charitable Choice and the language of the faith-based initiative allowed faith communities to use their religious background in their programming, implementation involved much confusion over the line between programming based on religious values and inherently sectarian activities, such as prayer or sharing faith [

16].

Further, since faith-based programming was characterized using Protestant or Evangelical language, Jewish, Mainline Protestant and some Peace church, organizations that highly valued supporting freedom of religion as a religious value in their programs denied that they were faith based. For example, most of our Jewish programs categorically announced that they offered secular programming using professionals, but when asked, explained that the basis for this decision was the fundamental Jewish values of Tikun Olam (repairing the world) and that using professionals reflected Jewish values that the greatest Mitzvah (blessing/good deed) was to offer the highest quality services that would lead to the best results. Like these Jewish institutions, we found religion embedded in the structures, strategies and programming of most Mainline Protestant, Catholic and Peace church organizations, which the standard typologies would label as faith related or faith background. These findings suggest that government needs to more carefully understand the diversity among religions and denominations it hopes to partner with, as well as the nature of the social networks that provide non-financial resources to both government and FBOs. It means understanding partnerships as a three-way interaction among government, FBOs and faith communities rather than a one-to-one relationships with either an FBO or faith community. I next look carefully at some key aspects of these differences across religions and denominations.

4.1. Religion Is Embedded in the Structures and Practices of FBOs, and Maintaining that Religion’s Values Is Critical to FBOs with Strong Ties to Their Faith

As outlined earlier, to date, the Bush faith-based initiative and supporting scholarship attempted to develop universal typologies of faith to identify faith-based organizations. While a full review of the various classification systems is beyond the scope of this paper, I review the general characteristics of the most popular scales here.

9 Most scholars agree that the religiosity of an organization exists on a continuum and that several dimensions of the organization’s structure and activities should be measured independently to understand the role of faith in organization practice. For example, Sider and Unruh [

47] present a typology that measures the characteristics of both organizations and programs, stating that a particular program may present more or fewer religious attributes than the organization as a whole. Their typology categorizes organizations from most religious (faith permeated) to secular based on such visible signs of religiosity as: (1) religious environment (building name, religious symbols displayed); (2) religious program content; (3) religious background of senior management; (4) criteria for selecting other staff; (5) sources of financial support and other resources; (6) organized religious practice of personnel; (7) mission statement and other materials; (8) founding organization and purpose; (9) affiliation with religious entities; (10) selection criteria for the board; (11) integration of religious content with other program components; and (12) expected connection between religious content and expected outcomes ([

47], pp. 112–15). The most religious organizations actively use religious background in choosing staff and board; religious statements permeate all aspects of the organization; and its programming and staff actively use religion (prayer, religious texts, etc.) when serving clients.

Both Monsma [

14,

76] and Ebaugh, Chafetz and Pipes [

48,

77] also use a series of visibly religious attributes to characterize dimensions of religiosity. Monsma used a list of ten religious attributes, identifying organizations and faith based/segmented and faith based/integrated based on the number and type of religious practices. The Ebaugh, Chafetz and Pipes ([

48], p. 264) scales used a similar list of 18 elements that fall into several categories: (1) visible religious symbols; (2) preference for religious candidates in staffing; (3) religiously explicit mission statement and materials; (4) prayer or use of religious material in programming with clients and staff; (5) indicators of proselytizing; and (6) staff understandings that their work serves a religious purpose (for example, put religious principles into action, demonstrate God’s love to clients). Through factor analysis, they identify three scales of service religiosity, staff religiosity and formal organization religiosity that behave independently. Most scales contain similar elements, and some scholars base religiosity on the numbers of religious staff involved in the organization and the pervasiveness of the founding religion in its programming and ethos (for example, [

20]). All of these scales share an emphasis on outside signs of religiosity, such as mission statements and symbols in buildings; percentage of funding, staff and participants connected to the founding religion; and open, individual religious practice, such as prayer, proselytizing and the use of religious materials in programming or organization practice.

Other scholars view the relationship between religious background and organization structure as far more complicated than represented on these scales [

6,

22,

53,

57,

75,

78]. Some note the diversity of religious expression, but look for universal aspects found in all religions to identify an organization as faith based [

79]. In contrast, the Faith and Organizations Project research demonstrates that religious culture and theology determine the way that religion is integrated into an organization, and religion is often embedded in the structure and culture of agency practices [

23,

24]. Further, as discussed elsewhere [

5], these popular scales reflect understandings of religion more prevalent in Protestant denominations, particularly Evangelical faith traditions. As the vignette on the Jewish organizations indicates, FBOs relying on strong religious backgrounds can appear secular in these typologies and may not want to be identified as faith based using the criteria from these universal scales. As with other scholars who have attempted to apply universal scales in evaluation research [

6,

53], our research suggests that FBOs and their faith communities should be encouraged to clarify for themselves and their government partners how their faith plays out in their organizations. Understanding practical theology is key to discerning how religious values are reflected in the organization and its programming.

Outlining practical theology for each religion and denomination is beyond the scope of this paper, but is available in other publications from the project [

24,

80]. Since practical theology changes across time and place, respecting the diversity of religious practice is particularly important when developing partnerships among faith communities, FBOs, government and other stakeholders. This is particularly true with Mainline Protestant and Evangelical organizations, where great diversity exists both within and across denominations or independent faith communities.

Understanding the nature of practical theology and religious culture for faith communities and FBOs is essential for partnerships because these religious elements will determine the resource structure for each FBO, outreach strategies to a faith community and the types of activities an organization is willing to undertake. The legal language regarding faith-based organizations stipulates that government cannot interfere with religious practice, but how this clause is interpreted can become a deciding issue for FBO participation in government initiatives. Religious exemption clauses are the basis for allowing faith communities to hire co-religionists and set certain personnel, structural and programmatic policies that reflect their theology. However, the exact nature of the religious exemption clause is established by local government. One vignette from our study illustrates the importance of government respecting specific religious values in order to partner with a wide range of FBOs.

10In March 2010, the District of Columbia implemented a same sex marriage law, stipulating that any agency that received government funds to provide services must offer equal treatment to same sex couples as anyone else served by their programs. Agencies also were required to provide the same benefits to same sex couples as any other married employee.

This new law caused a major dilemma for Catholic Charities of Washington DC. The agency is a large, multi-service organization that began as the Catholic Home Bureau in 1898 offering home placements for orphans. It incorporated in 1922 as Associated Catholic Charities and merged with several other Catholic organizations in 2004 under the Catholic Charities name to become a multi-site organization offering a wide array of services to area residents regardless of race, nationality or religion. At the time this law was debated, 68 percent of the Catholic Charities budget came from government, approximately twenty-two million dollars according to the Catholic News Agency.

11 The agency had government funding for foster care, independent living for older youth aging out of foster care, homeless services, services for people with persistent mental illness, people with developmental disabilities, families in crisis, immigrants and refugees. The agency was one of the top five in number, size and scope as a provider for foster care, accounting for 10 percent of private sector foster care in the area. While key leaders are Catholic, agency employees come from many different religious backgrounds. While Catholic values underlay program design and staff culture includes open religious activities, like requests for prayer on the email system behind the scenes, the services offered are deliberately secular or non-denominational.

Catholic Charities is described by its staff as “the social service arm of the Catholic church.” As determined by structures established by the Catholic Church in the U.S. in the early 20th century, Catholic Charities/Catholic Social Services are directly under the diocese, with the local bishop as titular head of the board. The first meeting of the National Catholic Charities Conference in 1910 at Catholic University included in its statement of purpose: “The National Conference … aims to preserve the organic spiritual character of Catholic charity.” Today, the Catholic values in Catholic Charities are supported through its strong ties to the local dioceses, as well as support from its National trade association, Catholic Charities USA. As such, local Catholic Charities must follow the teachings of the church, including “our religious teaching that marriage is between one man and one woman.”

12Analysis of the proposed law by the agency determined that it would impact on foster care because they would be expected to place children with same sex couples as foster parents and on employee benefit packages that covered spouses, but would not impact on any other direct service program funded by government. Agency leadership began to work with the archdiocese to formulate a response when the bill was first proposed. Agency and church leadership testified at numerous hearings, as well as attempting to negotiate behind the scenes for several months, with little results. A key leader explained: “We argued that the narrow religious exemption [clause] threatened our partnership to provide services with government—was in violation of our religious tenets which we can not do.” Describing the religious exemption clause in the law as “the narrowest in the country”, agency and church leaders together determined that the agency would need to get out of foster care altogether and change its spousal benefits so that they would provide equal treatment for all employees, but not cover same sex couples.

Once the decision was made, the agency worked with local government to find another agency with a similar philosophy to take over foster care. Ultimately, all staff and cases were transferred to a secular organization with Baptist roots, enabling complete continuity of care for children and families receiving foster care services, but ending over 100 years as a key provider of foster care in the DC area. Spousal benefits were changed so that anyone either joining the organization as new staff or marrying would not be offered health and other benefits for their spouse. While agency leaders were unhappy with these changes, they clearly stated that they had no choice as they could not allow DC government to “legislate the marriage policy of the Catholic church.” When asked what the organization would have preferred, a key leader commented:

In a perfect world what would have happened differently was government’s recognition of the public/private partnership with FBOs, allowing the organizations to operate within the teachings of their own religion. Providing the kind of religious exemption that allows church to be church and government to be government. Continue[ing] to provide foster care to couples that were of different genders. If all organizations said no [to allowing same sex couples to be foster parent], that would be an undue hardship on same sex couples. But they can get services elsewhere—we can be true to who we are.

This case demonstrates that even large, multi-service FBOs providing apparently secular services consider following their religious teachings paramount. Despite the loss of a key program, the agency clearly showed that government could not dictate internal policy. While the agency continues to partner with government, this incident necessarily changes and limits the nature of the relationship. This case also shows that FBOs are embedded in faith communities and respond to unique faith community structures. This discussion of role of religion in FBOs suggests three strategies for government initiatives partnering with FBOs:

- ■

Ask FBOs and faith communities to clarify the role of their religious traditions in their organization and explain the unique resources and limitations their faith background creates in partnerships with government and other entities.

- ■

Developing partnerships should involve working with both FBOs and faith communities, encouraging both to outline how they can best partner with government, what they expect from government and how they manage the relationship between FBOs and faith communities.

- ■

Religious exemption clauses should not attempt to legislate practical theology, but search for ways that government can partner with a diverse range of religiously-based institutions and ensure that all citizens have access to high quality services. The policy debate on this issue notes that guaranteeing options for people served is easier in diverse cities than in rural or smaller communities.

4.2. Faith Community Systems Shape How Different Religions and Denominations Structure Social Justice and Charity Work; Understanding These Structures Is Important for Government Outreach Efforts

The Faith and Organizations Project found three systems for organizing efforts to address any number of issues from a faith perspective that tracked back to the practical theology of a given group of religions or denominations. A detailed discussion of these systems is available elsewhere [

24,

80]. Here, I briefly outline key features of these systems and which religions and denominations use each system. I then discuss implications for government partnerships.

The six religions in the Maintaining Connections study fell into three strategies for organizing stewardship. As discussed in a companion paper [

80], these strategies reflected the practical theology of their founding religions, but also larger historical forces that influenced general strategies. As Wittberg

13 commented, the older religions—Jews and Catholics—shared strategies that saw stewardship and providing for those in need as the responsibility of communities as a whole. This obligation may be conceived as applying either to members of that religion exclusively or to the whole world. Our pilot study suggests that Muslims share a similar ethos [

23]. This expectation came from times when church and state were merged, with faith communities having primary responsibility for providing supports for their members. Even today, stewardship is organized through community-wide structures that reflect this history and a practical theology that asserts member responsibility as part of the community to take care of each other. We have labeled these systems institutionalized based on their reliance on centralized institutional structures. Catholic systems are integrated into either a diocese or religious order, sometimes via a local parish [

39,

41]. Jewish systems centralize all social and health services through Federations, with the synagogues remaining independent from the system [

27,

28]. While the formalization of community responsibility in 501c3 non-profits through the federation system is unique to the U.S., Jews in other countries view responsibility for community members in need communally and have developed a variety of structures with similar aims [

81]. Major features of the institutionalized systems are:

- ■

Centralized fundraising, volunteer recruitment, training and sometimes facilities management.

- ■

Strong tradition of centralized planning for the community or its institutions as a whole.

- ■

Centralized bodies occasionally encourage or force mergers or collaborations among organizations in the community for the greater good of the systems as a whole.

- ■

Ability to share resources across the system.

- ■

Strong networks of religiously-based, national umbrella associations, in addition to local centralized systems that also provide additional support and networks.

- ■

Tendency for FBOs outside of the centralized umbrella nevertheless to develop ties with other organizations in the faith. Elementary schools are connected with the wider faith community and the centralized umbrella (Federation, order or diocese), but most are also under the direct sponsorship of a local congregation.

- ■

The expectation that the faith community is responsible for the community as a whole, either envisioned as those of the same faith or all people.

Religions that came out of the Protestant Reformation instead stress the importance of individual action to support those in need. However, individuals are part of congregations, and these congregations are the central element in congregational systems. As Hall [

33] documents, the congregational system is the foundation for much of the U.S. non-profit sector, and these organization’s stewardship strategies often look similar to secular non-profits. Ministries or programs such as a church food pantry may begin as efforts within a congregation, but they usually become institutionalized as independent or semi-independent non-profits. Well-established FBOs maintain strong ties to congregations or at least retain vestiges of these congregational roots, through board appointments and other mechanisms. In this study, Mainline Protestants, some African American churches and “Peace churches”, such as the Quakers and Mennonites, fell into the congregational system. Some Evangelical groups use this system, as well. The major features of congregational systems are:

- ■

Ministries often formalize either as independent programs of their founding congregation(s) with independent advisory committees and separate accounting systems or as independent 501c3 organizations with limited ties to their original congregation. Some form as interfaith entities.

- ■

Organizations maintain ties to one or more congregations through board appointments, appeals for resources, volunteers and in-kind supports. Often, FBO by-laws stipulate that a percentage of board members be from the founding faith or founding congregations.

- ■

Most see volunteering as an important component of organizational activity and create volunteer opportunities for people from their congregation(s) because volunteering enables individuals to enact their faith or religious values.

- ■

Congregational system FBOs from Mainline Protestant and Quaker traditions often embed their faith in more general values, with many specifically stating that they value theological diversity within a general spiritual or Christian context. On principle, they do not proselytize.

- ■

Congregational system denominations create fewer umbrella organizations, such as professional associations for their FBOs, and the FBOs tend to belong to fewer umbrella groups.

Network systems are relatively new, although they harken back to the religious movements of the 19th century. Scholars note an increasing prevalence of these free standing, openly religious FBOs [

16]. In these systems, social networks formed around specific non-profits are the key element supporting those non-profits. However, these networks are value driven, and an organization can quickly lose support if it does not reflect the beliefs and practices of its supporting network. While face to face networks are often important in supporting these organizations, networks are just as likely to be virtual, drawing from people with similar goals even internationally to support a specific ministry. Network-based FBOs may be connected with one or multiple congregations, but their decision-making and support systems reside outside the congregational system. FBOs in network systems differ from those in congregational systems in two important ways: (1) the program or organization is supported by a network of individuals focused on a specific ministry; and (2) the people who work in these FBOs, either as volunteers or paid staff, share the faith approach of the organization’s founders and use this faith as a prime motivator in their work. In contrast, congregational organizations draw staff and volunteers who are interested in the service or ministry of the program, but who do not necessarily share similar approaches to faith or come from the religion of the founding congregation(s). The network-based FBOs in this study ranged from small emergency assistance programs founded by a single person to a multi-site pregnancy center working to prevent abortions and from a recently-founded evangelical Christian school to a nearly 200-year-old multi-service organization. Major features of network systems are:

- ■

FBOs frequently become a faith community for their staff, active volunteers and sometimes program participants, transcending any particular congregation.

- ■

Staff and volunteers share its founding faith and are primarily motivated by that faith.

- ■

Resources come through networks of like-minded believers, and often, FBOs highlight their faith or trust in God as a source for resources for the organization.

- ■

Since these FBOs are supported through personal networks, they are more likely to end when the pastor or founder moves on. In older, established FBOs, ministries can change as the leader’s calling or gospel vision changes.

- ■

One main subset of this group comprises evangelistic FBOs, for whom sharing their faith is a key element of the ministry.

Understanding which system a faith community or FBO uses influences how government or other partners can most effectively interact with FBOs and members of that faith. Non-financial partnerships often involve attempts to either disseminate information or generate civic engagement in the form of volunteers or other resources from a faith community for a government-sponsored or locality-wide initiative. Civic engagement refers to initiatives to work together for the common good [

38,

71,

82,

83]. As I discuss elsewhere [

82], social capital often generates civic engagement, particularly for faith communities, but well-known institutions can also draw civic engagement through the web or other media based on reputation rather than trust-based networks.

While reaching out to congregations through interfaith organizations or personal networks would make sense for congregational systems, policymakers would be wise to contact the centralized community-wide entity in institutionalized systems. These systems are likely to have centralized volunteer banks. Likewise in both systems, while some synagogues and parishes may be involved in social service activities, culturally, most faith community members expect that large initiatives will run through the diocese or Federation. Reaching out to congregations has proven less effective, especially with Catholics [

84]. At the other extreme, working through FBOs or the virtual networks that support them in order to reach people associated with network FBOs may be the most effective method of outreach.

Policymakers would also be wise to understand the differences among congregational denominations in developing outreach strategies. While working at NIH, I observed several initiatives that sought to reach African American churches through national denominational headquarters, presuming that information would be disseminated to local churches. This strategy made sense for denominations with hierarchical structures, like African Methodist Episcopal (AME), AME Zion or United Methodists, but proved unproductive in trying to reach loose confederations of Baptists and independent churches. The same differences appear among white, Latino and Asian Protestant denominations. In these cases, local-level social capital is far more effective than using national leaders to reach local faith communities. Further, understanding that congregational system FBOs may be the key contact point for people interested in working on a particular topic, it may make most sense to use the FBO to reach out to faith community members.

Differences between the three systems go beyond outreach strategies. As outlined above, each system has different strengths and weaknesses, as well as relying on very different understandings of religious obligations to provide for those in need or the role of religious expression in faith-based activities. For example, institutionalized systems’ planning processes could prove a major asset for policymakers, while congregational systems may be a primary source for volunteers. Since variation exists within systems and at the local level, policymakers would do well to not only identify the generalized system a faith community uses, but its local attributes. These brief observations on systems suggest the following policy strategies:

- ■

Understanding and identifying local faith community systems would facilitate outreach and partnership strategies for government and other stakeholders seeking to partner with faith communities.

- ■

Since each system comes out of faith traditions, understanding the practical theology and history behind each system is important in order to tailor partnership initiatives to mesh with the belief systems and the organizational strategies of that system.

4.3. Faith Community Umbrella Organizations Are an Important Underutilized Resource, but All Are Not the Same

Umbrella organizations can provide important resources for both FBOs and faith communities, as well as serving as a conduit between government and faith communities. The Bush faith-based initiative contracted with intermediaries to provide technical assistance through the Compassion Capital Fund and similar initiatives. Government also has a history of contracting directly with faith-based intermediaries, such as refugee resettlement contracts with national organizations affiliated with Catholics, Jews and several Mainline Protestant religions or contracts with Jewish Federations to provide services for the elderly, immigrants and refugees or other specific populations through a network of organizations. In this second example, intermediaries hold primary responsibility for a contract, coordinating work through member organizations and faith communities.

The brief discussion of faith community systems above demonstrates that umbrellas function in different ways in each system. Institutionalized system faith communities have highly developed networks of umbrella organizations at several levels. At the national level, Jewish umbrella professional associations for Federations, the Jewish community centers, Jewish family and vocational services and communal service networks provide technical support, networking for employment and an array of information. Catholic umbrellas like the Catholic Health Association and Catholic Charities USA provide similar supports, as well as national policy on various issues. At the regional level, Jewish federations vary significantly among themselves, but generally offer centralized fundraising, planning, leadership development and other resources to their faith communities and member FBOs. Catholic Health Care systems serve as similar umbrellas for their member hospitals, usually offering a combination of policy setting, the ability to share resources, planning and initiatives to help administrators understand the faith behind their work. For Catholics, both national umbrellas for the church, such as the U.S. Conference of Bishops and the Order headquarters, and local-level adjudicators, such as an archdiocese, provide faith community policy and some administrative umbrella functions. Local Catholic Charities organizations are sometimes umbrellas themselves with several quasi-independent units providing services to different populations. Policymakers would do well to rely on the expertise and organizing power of these umbrellas to develop partnerships and reach faith communities affiliated with them.

Congregational system umbrellas fall into two general categories. On the one hand, national umbrellas focused on refugee resettlement, disaster relief, international poverty and related issues, such as the Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, the Mennonite Central Committee and the Church World Service, have highly developed systems that simultaneously work with national policymakers and effectively network with both FBOs and congregations at the local level. These umbrellas provide an important resource for partnerships to provide services, marshal faith community support in times of disaster or disseminate information. However, at the local level, umbrellas tend to be smaller, more localized or entity specific. For example, Quakers have developed professional organizations for retirement communities and schools that offer technical support, common purchasing, quality assurance and insurance pools, as well as advice on maintaining the faith base in organizations. Sometimes, these organizations partner with Mennonites and Brethren. As such, they would serve as effective intermediaries to reach FBOs providing particular services.

Mainline Protestants have fewer of these organizations. The other umbrella institution in congregational systems, local interfaiths, vary widely from functioning as social service agencies to simply gatherings where pastors can share common concerns. Higher level adjudicatory bodies also vary greatly among congregational denominations, with some loose conferences having limited ability to reach member congregations. Denominations with adjudicatory levels, like Episcopals, Methodists, Lutherans and Quakers’ Yearly Meetings, vary greatly in their ability or willingness to create centralized programs or disseminate information at the local level. This great variation among congregational umbrellas suggests that policymakers would need to learn about the strengths and weaknesses of these local structures before asking them to serve as intermediaries to reach FBOs or faith communities or serve as partners in initiatives.

Umbrellas are fewer and looser among Evangelicals because of the fluid network nature of their institutions and the predominance of charismatic leaders among this faith tradition. Initiatives like Jim Wallis’s Call for Renewal suggest one example and networks among crisis pregnancy centers another. Our study did not focus on political or advocacy coalitions and cannot comment on strategies for government to partner with those networks. In general, our limited knowledge of these intermediaries suggests that policymakers would do well to assess their abilities and reach before working with them. They may prove powerful partners, but in other cases, using neutral intermediaries with strong social capital ties into Evangelical networks may be more productive.

This brief discussion of umbrellas suggests several policy strategies:

- ■

Policymakers would do well to identify existing faith community umbrella institutions and use them in partnerships or to provide intermediary services where appropriate.

- ■

Assess the capabilities of existing faith-based umbrellas as potential intermediaries or partners, developing partnerships based on their strengths and weaknesses.

- ■

Since umbrellas function differently in the three faith community systems, develop different strategies appropriate to their form, capacity, strengths and weaknesses.

4.4. Social Marketing Cannot Substitute for Developing Local Social Capital

Any form of partnership comes out of connections between government agents and faith community or FBO representatives, either at the national, regional or local level. Both financial and non-financial partnerships rely on the same mechanisms: developing trust-based relationships with both parties bringing something to the partnership. In the case of government, government is often presumed to offer funding for programs, access to other kinds of resources (expertise, goods like surplus dairy goods, health services like immunizations) or information useful to faith community residents. Faith communities, FBOs and other non-profits have services, resources in the form of space, volunteers, in-kind goods or funding and communities that can disseminate information (for example [

85]). However, these are only a few ways that government, faith communities, FBOs and other stakeholders can collaborate. Coalitions of government, faith community and faith-based leaders can work together to find solutions to a number of pressing issues. Faith communities have a long history of lobbying government on various forms of legislation and partnering on a variety of initiatives related to addressing human needs. This section focuses on problem solving at the local level, discussing both current strategies and potential ways they could be improved.

My experience with government collaborations at both the federal and local level reveals two main strategies for government to reach out to local communities. The first involves using media and dissemination of materials through local non-profits, FBOs and sometimes faith communities to share information or promote particular behaviors. Increasingly, these initiatives use sophisticated marketing techniques combined with connections through federal or regional intermediaries to reach a target audience, a technique known as social marketing. Examples include the billboards promoting marriage seen in many low income neighborhoods or the nutrition programs described earlier. While these marketing techniques have some impact, they do not have the long-term effects of developing local social capital, and the message comes top-down from government.

Government officials at all levels also use their connections to assemble coalitions, spread information on potential contracts and sponsor meetings of local community leaders to promote an initiative. The numerous state and local conferences to spread information on the faith-based initiatives are one example. As Sager ([

55], p. 106) notes, government officials are most likely to rely on known actors in a community or their personal networks in order to invite people to these events. As such, pre-existing social capital becomes the way that communities partner with government, limiting the breadth of partnerships. My work on training and welfare suggests the same is true for contracting, with government contracting primarily with agencies who had previously had successful government contracting experiences in the past. Advocacy interactions between government and local communities also usually involve known actors from a series of pre-existing coalitions or activist groups, with the most effective advocacy activities relying on a combination of testimony and behind the scenes social capital [