Aspects of Spirituality in German and Polish Adolescents and Young Adults—Factorial Structure of the ASP Students’ Questionnaire

Abstract

:1. Background

2. Development of the Aspects of Spirituality (ASP) Questionnaire

2.1. First Version of the Aspects of Spirituality Questionnaire (ASP Version 1.0)

- (1).

- Prayer, trust in God and shelter (11 items; alpha = .92);

- (2).

- Insight, awareness and wisdom (9 items; alpha = .87);

- (3).

- Transcendence conviction (5 items; alpha = .85);

- (4).

- Compassion, generosity and patience (5 items; alpha = .76);

- (5).

- Conscious interactions (4 items; alpha = .75);

- (6).

- Gratitude, reverence and respect (3 items; alpha = .58);

- (7).

- Equanimity (3 items; alpha = .68).

2.2. Second Version of the Aspects of Spirituality Questionnaire (ASP Version 2.1)

- (1).

- Religious orientation: Prayer / Trust in God (9 items; alpha = .93; religious views);

- (2).

- Search for Insight / Wisdom (7 items; alpha = .88; philosophical/existential views);

- (3).

- Conscious interactions (5 items; alpha = .83; relational views);

- (4).

- Transcendence conviction (4 items; alpha = .85; non-Christian spiritual views).

2.3. Validity of the Instrument

3. Factorial Structure of the ASP in German and Polish Students

3.1. Participants

| German sample | Polish sample | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 871 | 1,017 |

| Mean age (years) | 19.1 ± 2.5 | 18.0 ± 4.6 |

| Gender (%) * | ||

| Religious denomination (%) | ||

| Spiritual / religious self categorization (%) ** |

3.2. Factorial Structure in the German Sample

| Mean | SD | Difficulty Index (2.22/4 = 0.56) | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Cronbach’s alpha if item deleted | Factor loading | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | II | IV | IV | |||||||

| eigenvalue | 7.6 | 2.8 | 2.3 | 1.2 | 1.0 | ||||||

| 1. Religious Orientation: Prayer/Trust in God (eigenvalue = 7.6; alpha = .91) | |||||||||||

| Action | s36 Praying for myself and own concerns | 1.73 | 1.50 | 0.43 | .650 | .898 | .853 | ||||

| Emotion | s03 Trust in and turn to God | 1.75 | 1.38 | 0.44 | .681 | .897 | .847 | ||||

| Action | s35 Praying for others | 1.73 | 1.50 | 0.43 | .644 | .898 | .835 | ||||

| Intention | s39 Trying to express the Divine in the creation | 1.02 | 1.13 | 0.26 | .660 | .898 | .776 | ||||

| Emotion | s04 Feeling guided and sheltered | 1.90 | 1.21 | 0.48 | .651 | .898 | .749 | ||||

| Cognition | s33 Having a spiritual orientation in life | 1.77 | 1.29 | 0.44 | .696 | .897 | .683 | ||||

| Action | s37 Reading religious or spiritual books | 0.99 | 1.27 | 0.25 | .538 | .901 | .657 | ||||

| Emotion | s40 Do not feel alone, even when no one is with me | 2.87 | 1.41 | 0.72 | .596 | .899 | .622 | ||||

| Action | s38 Performing distinct rituals | 1.38 | 1.33 | 0.35 | .555 | .900 | .593 | ||||

| 2. Search for Insight/Wisdom (eigenvalue = 2.8; alpha = .83) | |||||||||||

| Action | s11 Aspiring to insight („Erkenntnis“) and truth | 2.81 | 1.09 | 0.70 | .453 | .902 | .784 | ||||

| Action | s13 Aspiring to broad awareness | 2.72 | 1.03 | 0.68 | .448 | .902 | .747 | ||||

| Intention | s10 Trying to develop wisdom | 2.44 | 1.16 | 0.61 | .411 | .903 | .673 | ||||

| Intention | s14 Life is a search and question for answers | 2.35 | 1.16 | 0.59 | .364 | .904 | .638 | ||||

| Action | s15 Searching for deep insight (“Einsicht”) in fabric of life | 2.17 | 1.17 | 0.54 | .481 | .902 | .632 | ||||

| Intention | s16 Trying to achieve frankness/wideness of the spirit | 1.88 | 1.25 | 0.47 | .577 | .900 | .609 | .346 | |||

| Action | s12 Aspiring to beauty and goodness | 2.49 | 1.07 | 0.62 | .337 | .904 | .595 | ||||

| 3. Transcendence conviction (eigenvalue = 1.3; alpha = .74) | |||||||||||

| Cognition | s08 Convinced of a rebirth of man (or his soul) | 1.82 | 1.37 | 0.46 | .438 | .903 | .713 | ||||

| Cognition | s06 Convinced of existence of higher powers and beings | 2.42 | 1.33 | 0.61 | .590 | .899 | .364 | .656 | |||

| Cognition | s05 Soul has his origin in a higher dimension | 1.82 | 1.36 | 0.46 | .631 | .898 | .420 | .642 | |||

| Cognition | s19 Convinced that man is a spiritual being | 2.49 | 1.19 | 0.62 | .511 | .901 | .304 | .510 | |||

| 4. Conscious interactions/Compassion (eigenvalue = 2.3; alpha = .74) | |||||||||||

| Intention | s28 Trying to develop compassion | 3.15 | 0.90 | 0.79 | .358 | .904 | .769 | ||||

| Intention | s26 Trying to practice generosity | 2.94 | 0.86 | 0.74 | .223 | .906 | .759 | ||||

| Action | s21 Conscious interaction with myself | 2.92 | 0.97 | 0.73 | .209 | .906 | .804 | ||||

| Action | s22 Conscious interaction with others | 3.21 | 0.77 | 0.80 | .248 | .905 | .520 | .643 | |||

| Action | s23 Conscious interaction with environment | 2.82 | 0.91 | 0.71 | .258 | .905 | .460 | .588 | |||

3.3. Factorial Structure in the Polish Sample

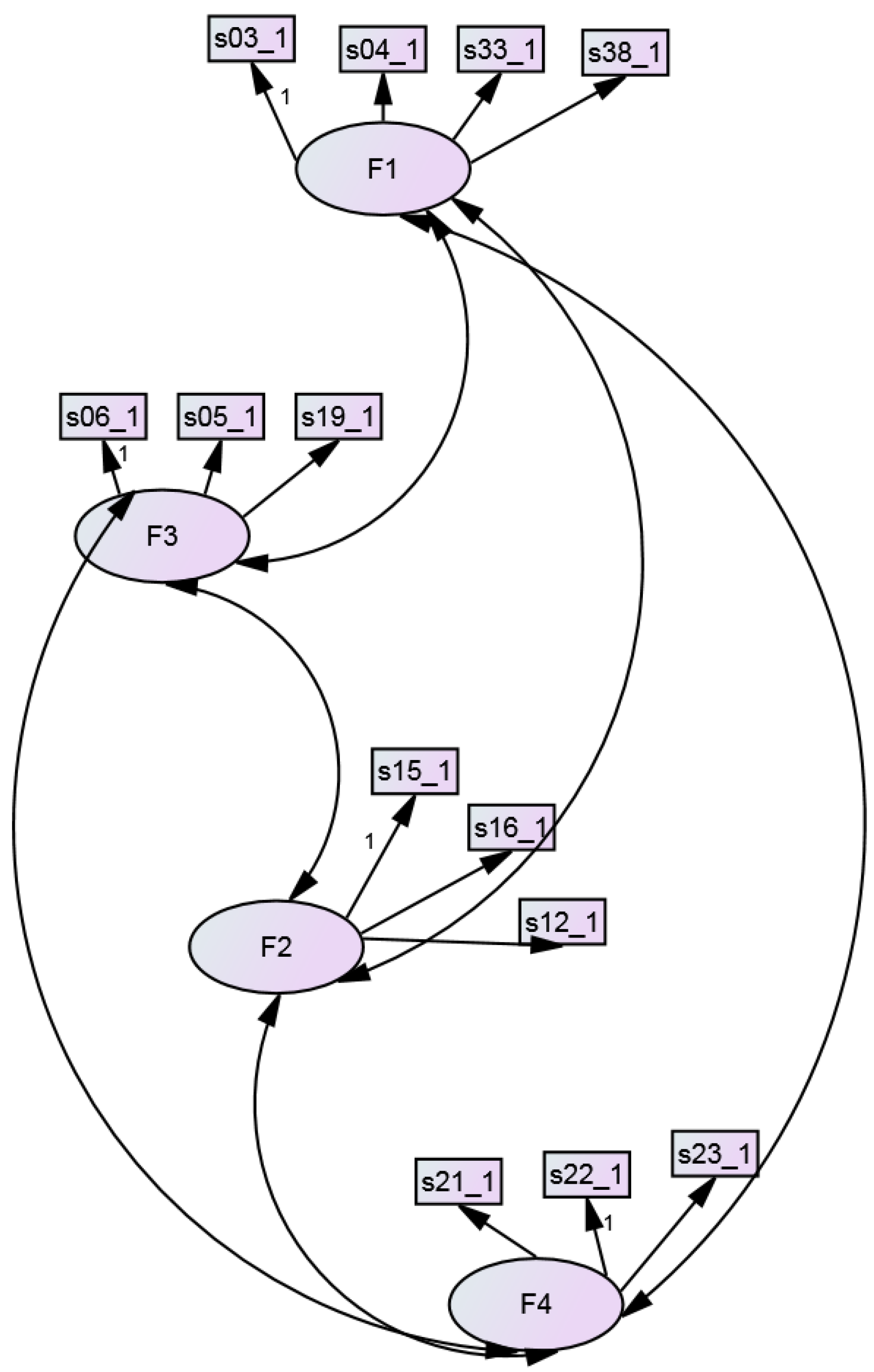

3.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

- -

- Polish students: ×2 (33) = 109.61, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.048,

- -

- German students: ×2 (33) = 45.72, p = 0.069, CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.021.

| Mean | SD | Difficulty Index (2.50 / 4 = 0.63) | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Cronbach’s alpha if item deleted | Factor loading | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | II | IV | |||||||

| eigenvalue | 8.7 | 2.8 | 1.4 | 1.2 | ||||||

| 1. Religious Orientation: Prayer/Trust in God (eigenvalue = 8.7; alpha = .91) | ||||||||||

| Intention | s39 Trying to express the Divine in the creation | 2.17 | 1.33 | 0.54 | .692 | .926 | .758 | |||

| Action | s35 Praying for others | 2.27 | 1.41 | 0.57 | .703 | .926 | .726 | .358 | ||

| Action | s37 Reading religious or spiritual books | 1.58 | 1.38 | 0.40 | .521 | .930 | .722 | |||

| Action | s38 Performing distinct rituals | 2.08 | 1.28 | 0.52 | .588 | .928 | .700 | |||

| Emotion | s40 Do not feel alone, even when no one is with me | 2.40 | 1.33 | 0.60 | .634 | .928 | .695 | |||

| Action | s36 Praying for myself and own concerns | 2.38 | 1.40 | 0.60 | .688 | .927 | .638 | .448 | ||

| Cognition | s33 Having a spiritual orientation in life | 2.20 | 1.27 | 0.55 | .733 | .926 | .632 | .365 | ||

| Emotion | s03 Trust in and turn to God | 2.59 | 1.40 | 0.65 | .704 | .926 | .566 | .538 | ||

| Intention | s26 Trying to practice generosity | 2.26 | 1.18 | 0.57 | .496 | .930 | .524 | .411 | ||

| Emotion | s04 Feeling guided and sheltered | 2.29 | 1.18 | 0.57 | - | - | - | |||

| 2. Search for Insight/Wisdom (eigenvalue = 2.8; alpha = .86) | ||||||||||

| Intention | s14 Life is a search and question for answers | 2.68 | 1.12 | 0.67 | .534 | .929 | .778 | |||

| Action | s13 Aspiring to broad awareness | 2.86 | 1.04 | 0.72 | .516 | .929 | .754 | |||

| Action | s15 Searching for deep insight (“Einsicht”) in fabric of life | 2.90 | 1.04 | 0.73 | .483 | .930 | .703 | |||

| Action | s11 Aspiring to insight (“Erkenntnis”) and truth | 2.93 | 1.06 | 0.73 | .628 | .928 | .600 | .426 | ||

| Intention | s16 Trying to achieve frankness/wideness of the spirit | 2.49 | 1.14 | 0.62 | .643 | .928 | .358 | .587 | ||

| Action | s12 Aspiring to beauty and goodness | 2.85 | 1.06 | 0.71 | .622 | .928 | .584 | .417 | ||

| Intention | s10 Trying to develop wisdom | 3.01 | 0.98 | 0.75 | - | - | - | |||

| 3. Conscious interactions / Compassion (eigenvalue = 1.4; alpha = .80) | ||||||||||

| Action | s22 Conscious interaction with others | 2.90 | 1.00 | 0.73 | .534 | .929 | .827 | |||

| Action | s23 Conscious interaction with environment | 2.83 | 1.00 | 0.71 | .533 | .929 | .791 | |||

| Action | s21 Conscious interaction with myself | 2.88 | 1.04 | 0.72 | .431 | .931 | .706 | |||

| Intention | s28 Trying to develop compassion | 2.66 | 1.15 | 0.67 | .544 | .929 | .417 | .525 | ||

| 4. Transcendence conviction (eigenvalue = 1.2; alpha = .77) | ||||||||||

| Cognition | s06 Convinced of existence of higher powers and beings | 2.33 | 1.45 | 0.58 | .468 | .931 | .698 | |||

| Cognition | s05 Soul has his origin in a higher dimension | 2.24 | 1.36 | 0.56 | .664 | .927 | .350 | .697 | ||

| Cognition | s08 Convinced of a rebirth of man (or his soul) | 2.05 | 1.38 | 0.51 | .442 | .931 | .584 | |||

| Cognition | s19 Convinced that man is a spiritual being | 2.68 | 1.21 | 0.67 | .728 | .926 | .375 | .353 | .516 | |

| German students | Polish students | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Factor 4 | Factor 3 | Factor 2 | Factor 1 | Factor 4 | Factor 3 | Factor 2 | Factor 1 |

| s23 | 0.22 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.07 |

| s22 | 0.36 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.39 | –0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| s21 | 0.14 | –0.03 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.18 | –0.07 | –0.01 | –0.10 |

| s19 | −0.02 | 0.14 | –0.01 | 0.08 | –0.09 | 0.26 | –0.04 | 0.30 |

| s05 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.11 |

| s06 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| s12 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.16 | –0.04 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.34 | 0.06 |

| s16 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.33 | –0.12 | 0.08 | –0.05 | 0.28 | –0.09 |

| s15 | –0.01 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.09 | –0.06 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.08 |

| s38 | 0.01 | 0.05 | –0.03 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 0.03 | –0.01 | 0.06 |

| s33 | 0.01 | 0.07 | –0.03 | 0.27 | 0.02 | 0.09 | –0.03 | 0.19 |

| s04 | 0.00 | 0.14 | –0.01 | 0.35 | –0.02 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.23 |

| s03 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.15 |

| German students | Polish students | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | S.E. | p | Estimate | S.E. | p | |

| F2–F4 | 0.034 | 0.022 | 0.118 | 0.33 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| F3–F4 | 0.094 | 0.027 | 0.001 | 0.29 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| F1–F4 | 0.135 | 0.026 | 0.001 | 0.44 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| F2–F3 | 0.495 | 0.048 | 0.001 | 0.31 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| F1–F3 | 0.818 | 0.058 | 0.001 | 0.71 | 0.06 | 0.00 |

| F1–F2 | 0.415 | 0.045 | 0.001 | 0.46 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

3.5. ASP Scores in German and Polish Students

| RO | RO-SF | SIW | SIW-SF | CI/CG | CI-SF | TC | TC-SF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | mean | 42.0 | 42.4 | 60.2 | 54.5 | 75.2 | 74.7 | 53.4 | 56.0 |

| SD | 25.8 | 25.9 | 20.0 | 22.1 | 15.6 | 18.0 | 24.7 | 26.0 | |

| Gender | |||||||||

| female | mean | 45.7 | 45.8 | 60.9 | 55.9 | 78.0 | 77.3 | 56.8 | 59.6 |

| SD | 25.1 | 25.4 | 19.9 | 21.8 | 13.7 | 15.7 | 23.7 | 25.1 | |

| male | mean | 37.4 | 38.3 | 59.3 | 52.7 | 71.8 | 71.3 | 49.3 | 51.8 |

| SD | 25.8 | 26.1 | 20.1 | 22.4 | 17.2 | 20.1 | 25.4 | 26.5 | |

| F value | 22.8 | 18.3 | 1.3 | 4.5 | 35.0 | 23.9 | 19.9 | 19.8 | |

| p value | <.0001 | <.0001 | n.s. | .034 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |

| SpR self categorization | |||||||||

| R/S (R+S+ / R+S− / R−S+) | mean | 61.2 | 61.1 | 67.8 | 63.4 | 79.0 | 78.1 | 67.8 | 71.0 |

| SD | 22.2 | 21.6 | 17.3 | 19.6 | 13.8 | 16.4 | 20.7 | 21.6 | |

| R−S− | mean | 30.2 | 60.9 | 55.5 | 49.0 | 72.9 | 72.5 | 44.5 | 46.8 |

| SD | 20.1 | 21.2 | 20.1 | 21.8 | 16.2 | 18.7 | 22.8 | 24.2 | |

| F value | 449.9 | 410.2 | 85.6 | 96.8 | 32.4 | 20.0 | 231.2 | 223.2 | |

| p value | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |

| RO | RO-SF | SIW | SIW-SF | CI/CG | CI-SF | TC | TC-SF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | mean | 55.5 | 57.3 | 69.6 | 68.7 | 70.4 | 71.6 | 58.2 | 60.5 |

| SD | 24.6 | 24.8 | 20.6 | 21.7 | 20.7 | 22.0 | 25.8 | 27.3 | |

| Gender | |||||||||

| female | mean | 57.4 | 59.2 | 70.6 | 70.2 | 72.2 | 72.8 | 59.5 | 62.0 |

| SD | 23.3 | 23.4 | 20.3 | 20.9 | 20.4 | 21.7 | 25.2 | 26.6 | |

| male | mean | 52.6 | 54.4 | 68.1 | 67.0 | 68.8 | 70.6 | 56.4 | 58.9 |

| SD | 25.6 | 25.9 | 21.5 | 22.8 | 21.5 | 22.9 | 26.2 | 27.9 | |

| F value | 8.7 | 8.4 | 3.0 | 5.1 | 6.2 | 2.3 | 3.3 | 3.0 | |

| p value | .003 | .004 | .082 | .024 | .013 | n.s. | .068 | .083 | |

| SpR self categorization | |||||||||

| R/S (R+S+ / R+S− / R−S+) | mean | 69.0 | 70.1 | 75.6 | 75.3 | 74.8 | 75.3 | 67.6 | 70.7 |

| SD | 17.4 | 18.3 | 17.6 | 18.6 | 18.9 | 20.4 | 22.2 | 23.7 | |

| R−S− | mean | 36.8 | 40.0 | 61.5 | 59.9 | 64.2 | 66.5 | 45.4 | 46.8 |

| SD | 20.8 | 21.8 | 21.4 | 22.2 | 21.4 | 23.0 | 24.9 | 25.9 | |

| F value | 699.1 | 551.5 | 129.2 | 140.9 | 67.5 | 40.0 | 216.1 | 226.1 | |

| p value | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |

4. Discussion

| Search for Insight/Wisdom (SIW-SF) | Conscious interactions (CI-SF) | Transcendence conviction (TC-SF) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlations in the German sample | |||

| Religious Orientation (RO-SF) | .410 ** | .177 ** | .604 ** |

| Search for Insight/Wisdom (SIW-SF) | .113 ** | .516** | |

| Conscious interactions (CI-SF) | .161 ** | ||

| Correlations in the Polish sample | |||

| Religious Orientation (RO-SF) | .525 ** | .360 ** | .668 ** |

| Search for Insight/Wisdom (SIW-SF) | .542 ** | .511 ** | |

| Conscious interactions (CI-SF) | .330 ** |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- William James. Varieties of Religious Experience. A Study on the Human Nature. Rockville: Arc Manor, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon W. Allport. “The Individual and His Religion: A Psychological Interpretation.” New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon W. Allport, and James M. Ross. “Personal religious orientation and prejudice.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 5 (1967): 432–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harold G. Koenig. “Concerns about measuring ‘spirituality’ in research.” Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 196 (2008): 349–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaus Baumann. “Religiöser Glaube, persönliche Spiritualität und Gesundheit. Überlegungen und Fragen im interdisziplinären Feld von Theologie und Religionswissenschaft, Medizin und Psychotherapie.” Zeitschrift für medizinische Ethik 55 (2009): 131–44. [Google Scholar]

- Arndt Büssing. “Measures of Spirituality in Health Care.” In Oxford Textbook of Spirituality in Healthcare. Edited by Mark R. Cobb, Christina M. Puchalski and Bruce Rumbold. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012, pp. 323–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gert Pickel. “Religionsmonitor. Verstehen was verbindet. Religiosität im Internationalen Vergleich.” Bertelsmann Stiftung. 2013. Available online: http://www.religionsmonitor.de/pdf/Religionsmonitor_IntVergleich.pdf.

- Arndt Büssing, Annina Janko, Klaus Baumann, Niels Christian Hvidt, and Andreas Kopf. “Spiritual needs among patients with chronic pain diseases and cancer living in a secular society.” Pain Medicine 14 (2013): 1362–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian Zwingmann, Constantin Klein, and Arndt Büssing. “Measuring Religiosity/Spirituality: Theoretical Differentiations and Characterizations of Instruments.” Religions 2 (2011): 345–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harold G. Koenig, Keith Meador, and George R. Parkerson. “Religion Index for Psychiatric Research: A 5-item Measure for Use in Health Outcome Studies.” American Journal of Psychiatry 154 (1997): 885–86. [Google Scholar]

- Jimmie C. Holland, Kathryn M. Kash, Steven Passik, Melissa K. Gronert, Antonio Sison, Marguerite Lederberg, Simcha M. Russak, Lea Baider, and Bernard Fox. “A brief spiritual beliefs inventory for use in quality of life research in life-threatening illness.” Psychooncology 7 (1998): 460–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn G. Underwood, and Jeanne A. Teresi. “The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale: Development, Theoretical Description, Reliability, Exploratory Factor Analysis, and Preliminary Construct Validity Using Health-Related Data.” Annals of Behavioral Medicine 24 (2002): 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt Büssing, Thomas Ostermann, and Peter F. Matthiessen. “Distinct expressions of vital spirituality. The ASP questionnaire as an explorative research tool.” Journal of Religion and Health 46 (2007): 267–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt Büssing, Axel Föller-Mancini, and Jennifer Gidley. “Aspects of Spirituality in Adolescents.” International Journal of Children’s Spirituality 15 (2010): 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt Büssing. “‘Spiritualität’—Worüber reden wir? ” In Spiritualität, Krankheit und Heilung—Bedeutung und Ausdrucksformen der Spiritualität in der Medizin. Edited by Arndt Büssing, Thomas Ostermann, Michaela Glöckler and Peter F. Matthiessen. Frankfurt, Germany: VAS—Verlag für Akademische Schriften, 2006, pp. 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Donna S. Martsolf, and Jacqueline R. Mickley. “The concept of spirituality in nursing theories: Differing world-views and extent of focus.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 27 (1998): 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt Büssing, Philipp Kerksieck, Axel Föller-Mancini, and Klaus Baumann. “Aspects of spirituality and ideals to help in adolescents from Christian academic high schools.” International Journal of Children’s Spirituality 17 (2012): 99–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt Büssing, Thomas Ostermann, and Peter F. Matthiessen. “Role of religion and spirituality in medical patients: Confirmatory results with the SpREUK questionnaire.” Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 3 (2005): 10. Available online: http://www.hqlo.com/content/3/1/10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arndt Büssing. “Spirituality as a Resource to Rely on in Chronic Illness: The SpREUK Questionnaire.” Religions 1 (2010): 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Büssing, A.; Pilchowska, I.; Baumann, K.; Surzykiewicz, J. Aspects of Spirituality in German and Polish Adolescents and Young Adults—Factorial Structure of the ASP Students’ Questionnaire. Religions 2014, 5, 109-125. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel5010109

Büssing A, Pilchowska I, Baumann K, Surzykiewicz J. Aspects of Spirituality in German and Polish Adolescents and Young Adults—Factorial Structure of the ASP Students’ Questionnaire. Religions. 2014; 5(1):109-125. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel5010109

Chicago/Turabian StyleBüssing, Arndt, Iwona Pilchowska, Klaus Baumann, and Janusz Surzykiewicz. 2014. "Aspects of Spirituality in German and Polish Adolescents and Young Adults—Factorial Structure of the ASP Students’ Questionnaire" Religions 5, no. 1: 109-125. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel5010109