1. Introduction

Consumer interest in local and regional food in the United States (US) has increased substantially over the last four decades. For the most part, this has been measured by the growing demand in direct-to-consumer marketing, which increased from $551 million in 1997 to $1.3 billion in 2012 [

1].

Several factors are motivating consumers to purchase locally grown foods. Their top reasons for buying locally grown foods in grocery stores were: freshness (83 percent), supporting the local economy (68 percent), and taste (53 percent) [

2]. They are also interested in the environmental impacts of growing food and supporting family farms [

3]. The nutritional value of local food was also cited as a common reason. Additionally, local foods are part of a food system that supports social relationships that may or may not be geographically nearby [

4]. In short, consumers want “food with a face on it”.

Institutional food service is a growing market channel for local foods. Schools, colleges, universities, corporate cafeterias, hospitals, and government food service sites are all expanding their local foods programs. Feenstra et al. [

5] found that colleges and universities in California wanted produce that was locally grown and sustainably produced, but that was also reasonably priced. The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) now has an entire program devoted to supporting Farm to School programs nationwide and tracks progress through a Farm to School census every two years. The most recent census for school year 2013–2014 found that schools purchased $790 million in local food [

6]. Institutional buyers are responding to consumer demand.

Supply chains for purchasing local or regional food for retail or institutional buyers are often different than direct-to-consumer channels. The scale of farmers and ranchers using intermediated channels also differs. Some producers are utilizing food supply chains that are characterized by

partnerships throughout the supply chain from producers to buyers, and who share a commitment to environmental, social and economic values. The “values” associated with the foods may be that they are locally produced, grown by small or mid-scale farms, or production practices enhance the environment and/or worker welfare. Farmers, in particular, receive a premium for these values. Such food supply chains

are commonly called “values-based supply chains” (VBSCs) [

5,

7,

8]. Unfortunately, there are no data available regarding the numbers of farms and ranches using such supply chains, nor are there data regarding the sales they generate.

The farmers and ranchers supplying these values-based supply chains (VBSCs) are more likely to be part of a sector called “Agriculture of the Middle”—too large for the short chain direct markets, but too small for the large commodity markets. They generally fall into the $50,000–$500,000 gross sales category. The number of farms in this “middle” size category has been in decline for several decades. They rely largely on their farm income to survive and contribute substantially to the economic viability of rural communities and land stewardship nationwide. Concern has been mounting that if these farms continue to fail, the structure of agriculture will become even more bifurcated (with mostly very small or very large farms on the landscape), and the environmental, social and economic values that mid-scale farmers embody will disappear [

9].

VBSCs are increasingly seen as opportunities to create strategic business models for farmers and ranchers of the middle. These farmers and ranchers are most likely to fit this model if they produce significant volumes of high quality, differentiated food products; can operate on a regional scale; and are willing to distribute profits among strategic partners [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Key benefits of VBSCs for participating farmers include: (1) they are more

transparent than conventional supply chains; values are communicated throughout the chain, providing buyers and consumers with information they need to pay more for these foods; (2) they provide

higher prices to participating farmers due to the chain’s strategic partnerships and the fact that buyers are willing to compensate farmers for particular values; and (3) buyers in these supply chains are more willing to negotiate with farmers and often absorb some of the transaction costs and

work with farmers or ranchers to source products on an on-going basis [

14]. Overall, the goals of VBSCs are to: (1) provide greater economic stability for producers and others along the supply chain; and (2) provide high quality, regional food to consumers.

Other researchers have described supply chains similar to VBSCs as “alternative food networks” [

15] or “nested markets” [

16]. There are strong similarities between VBSCs and alternative food networks. VBSCs were developed to enhance the viability of mid-scale food producers and rural communities in the US. There is also considerable research regarding the development of alternative food networks to revitalize small farms and rural economies in Europe. Sonnino and Marsden [

15] present three case studies of alternative food networks in England that were similarly developed to reconfigure/re-localize food producers who could not compete on a price basis in commodity markets. Sonnino and Marsden [

17] (p. 181) state that alternative food networks are “variously and loosely defined in terms of ‘quality’, ‘transparency’, and ‘locality’.

Stevenson and Pirog [

8] describe how VBSCs rely on shared information among supply chain partners (transparency) to improve productivity, enable rapid response to market changes and effectively engage customers. Sonnino and Marsden [

17] (p. 195) refer to transparency within two types of spatial relationships in alternative food systems. First, under “processing and retailing”, they describe alternative food networks as “… traceable, and transparent; spatially referenced and designed qualities” (p. 195). Second, under “associational frameworks”, they refer to alternative food networks as being “relational, trust-based … competitive but sometimes collaborative”. In the case studies examined by Roep and Wiskerke [

18], the governance process involves transparency, strategic partnerships and shared decisionmaking—elements that also characterize VBSCs.

For farmers, earning a premium above commodity prices for the environmental and/or social benefits that they generate through their production practices is an objective of VBSCs. These benefits also contribute to the higher quality of foods in the alternative food networks analyzed by Goodman [

19], Ilbery et al. [

20], and Sonnino and Marsden [

15,

17]. Sonnino and Marsden [

17] (p. 183) state that, unlike the globalized conventional food system, a key characteristic of alternative food networks is “… their capacity to re-socialize or re-spatialize food” by either its production area or even a specific farm, which provides a quality dimension. van der Ploeg et al. [

16] (p. 139) define nested markets as “… alternative agri-food chains which are embedded or (nested) in normative frameworks (and associated forms of governance) which are rooted in the social movements, institutional frameworks and/or policy programmes out of which they emerge … they are markets with a particular focus (sometimes underpinned by a specific brand, or a specific quality definition, or by relations of solidarity, or specific policy objectives, etc.)”. Nested markets, alternative food networks and VBSCs, then, all seem to have several common elements that engage food system partners in environmental, social and economic sustainability in regional food systems.

Since the concept of VBSCs has emerged, various case studies have examined how value chain businesses have fared using this model. Lev and Stevenson [

13] highlight the advantages of acting collectively and joint learning within and across the value chains in four cases—(1) Country Natural Beef, a beef rancher cooperative in the NW US; (2) Cooperative Regions of Organic Producer Pools (CROPP)/Organic Valley, a multi-regional organic farmer cooperative; (3) Shepherd’s Grain, a business marketing sustainably grown wheat in the NW United States; and (4) Red Tomato, a nonprofit, domestic fair trade business marketing regional produce in the northeastern US. Feenstra et al. [

21] describe key findings of five VBSCs in California, namely that: (1) VBSCs are not neat and linear, but complex and more like networks; (2) customers all want to know the story of the farm, its scale, where it is located and how food was produced; (3) aggregators or regional food hubs are emerging to distribute products for many smaller producers; and (4) telling an authentic story is often more important than “local”. Two of these cases and four others were part of an analysis of how access to capital, regulatory/business policy and business acumen influence the development of food VBSCs in the Western US [

7]. Although VBSCs can support farmers and ranchers of the middle in various contexts, more attention is needed regarding the extent to which values are communicated along the supply chain and how to develop appropriately scaled infrastructure for this mid-scale sector.

One emerging business structure that can be part of VBSCs is a “food hub”. The USDA defines a “food hub” as “a business or organization that actively manages the aggregation, distribution, and marketing of source-identified food products primarily from local and regional producers to strengthen their ability to satisfy wholesale, retail, and institutional demand” [

22]. Low et al. [

1] (p. 13) noted that “regional food hubs have emerged as collaborative enterprises for moving local foods into larger mainstream markets, providing scale-appropriate markets for mid-sized farmers …”. Food hubs can and do support “Agriculture of the Middle” farmers and ranchers in accessing local markets.

As the concept of VBSCs matures, it is imperative to continue to investigate further to understand the ongoing challenges faced by different supply chain partners across the value chain. This paper will use a case study approach to examine three intended benefits (and potential challenges) of VBSCs: (1) transparency in communicating values throughout the supply chain; (2) the ease with which VBSCs can coordinate purchases from small and mid-scale producers; and (3) the extent to which VBSCs provide fair prices to farmers versus remaining competitive in the marketplace.

2. Methods

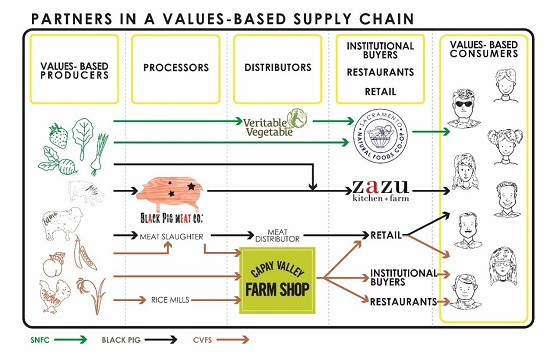

For this study, we chose three different VBSCs in Northern California, focusing on key partners at different entry points within each chain (see

Figure 1). Each chain is a regional supply chain, consistent with the spatial limitations included in the definition of values-based supply chains. We intentionally chose supply chains with different types of products in order to explore potential differences between meat and produce supply chains.

The first—Black Pig Meat Company—can be characterized as a processed meat/specialty food business. They process their own salumi (Italian cold cuts predominantly made from pork, of which salami is one variety) and work with partners throughout the supply chain to purchase, process, distribute and sell specialty bacon. The second case—Sacramento Natural Foods Co-op—is a cooperative grocery store that works closely with partners throughout the supply chain—from farmers to distributors—to sell only organic food. We also include information about the primary organic produce distributor used by the cooperative grocer as part of this case since their values are so complementary. This VBSC is very mature; it was established in 1978. Our third case—Capay Valley Farm Shop—is a small, regional “food hub”—a business that aggregates food products from small and mid-scale farmers in the area and distributes them to the broader region of Northern California. These three cases allowed us to view VBSCs from different perspectives along the chain and to note differences in supply chains for different product types (e.g., meat versus produce).

To elicit in-depth information from these supply chains, we opted to use case studies and followed Yin’s approach [

23]. We created an interview guide to collect data about each of these businesses and their supply chains, including: basic information about the size and nature of the business; values the business espouses; pricing considerations regarding procuring and marketing products from small and mid-scale farms; logistics of sourcing specialty/local/organic food from their suppliers; information/values about their suppliers and how that information is communicated throughout the chain; challenges and benefits of working with small and mid-scale suppliers in particular; the motivations for doing so; decisions or challenges about fair pricing; and final thoughts about the future of their business as part of a VBSC. We conducted several interviews with key partners in each case study during winter/spring of 2016, either in person or by phone to collect the primary data for this study. Follow-up data were collected by phone or email. Since we have known the leaders in each of these case studies for years, we also used supplementary data from previous conversations. Some interviewees provided written materials in which their business had been showcased. We also used material from all of their websites.

We now describe the key elements of each of the three case studies.

3. Findings

3.1. Black Pig Meat Company/Zazu Kitchen and Farm—(Chefs Duskie Estes and John Stewart, Sebastopol, California)

The Black Pig Meat Company (Black Pig) was created in 2005 by Chefs Duskie Estes and her husband, John Stewart, of Zazu Kitchen and Farm [

24] in Sebastopol, California, USA. Duskie and John decided to focus on sustainable meat and process their own salumi for the restaurant. They source sustainably grown hogs that they use to make their signature bacon and other pork products. In 2015, Black Pig’s revenues totaled approximately $300,000; sales were split fairly evenly, between distributors and direct to consumers at the restaurant. The products are sold at retailers across the country from California to New York.

Today, about 30% of the restaurant’s produce comes from a farm a few minutes from the restaurant. It is also the source of some of Zazu’s chicken, duck, turkey, pork, sheep, rabbits and goats.

3.1.1. Making Sustainable Bacon and Salumi

Since 2005, Duskie and John have been making bacon, and selling it through retail and wholesale outlets and through their restaurant. They have used two co-packers (the Sonoma Meat Company which is only six miles from their restaurant, and Carlton Farms in Oregon (about 600 miles to the north) that are committed to quality processing and using Duskie and John’s curing recipe. Both co-packers operate USDA-inspected meat processing facilities. Duskie maintains that Black Pig’s bacon has superior flavor, while bacon usually found at stores is “wet cured” and “smoked” with liquid smoke in less than a day, their bacon is dry-cured with brown sugar for up to 21 days and then finished with applewood smoking for another 12 h.

Every Tuesday, the Zazu restaurant closes so Duskie and John can turn the kitchen into a state-inspected “custom exempt” meat processing facility. This means that the meat (salumi and bacon made from California-grown hogs) they process can only be served or sold by the pound “to go” at their restaurant. To facilitate this process, John became a California Department of Food and Agriculture processing inspector. Regional inspectors visit their operation two to three times per month, often unannounced. Duskie and John serve the salumi they make on their menu at the restaurant the other six days of the week.

The values Duskie and John promote are selling quality processed meat (particularly bacon) from animals that are sustainably raised on family farms. The heritage breed pigs they source are raised without antibiotics or hormones, have vegetarian feed, roam free in pastures, and the sows are not put into farrowing crates to give birth to their piglets.

3.1.2. Transparency/Communication about Values

Duskie and John educate their patrons about the food they eat through what they serve at their restaurant and the information they provide. Many of the menu items identify the farm, ranch, bakery, dairy or cheesemaker from which the items came. However, Zazu does not identify the hog farm suppliers for their processed pork products on their menu because there are multiple farms involved. The Zazu website also lists many of their farm suppliers.

Duskie also educates her patrons about how Zazu uses the whole animal. To do that, she offers “pig tastings” at the restaurant, which showcase various parts of the pig, from tail to snout, cooked in different ways. The “pig tastings” are clearly another way to educate consumers about the importance of using the whole animal in order to reduce waste and support smaller producers in a regional food system.

Zazu staff are educated about how the business supports sustainability values throughout the supply chain. They then share this information with customers at the restaurant. In addition, Duskie trains her kitchen staff about how to cut up and prepare all of the pig. She insists that all of her kitchen staff witness a pig being slaughtered so they understand and respect the meat they are preparing and serving.

3.1.3. Sourcing from Small and Mid-Scale Farms

Duskie buys her hogs from three small, regional farms and one large farm in Iowa. These farms are all careful about what they feed their pigs. The pigs are then processed at two meat processing companies. After the bacon is processed at Sonoma Meat Company, Duskie and John take some of it to Golden Gate Meat Company to distribute to local grocers and restaurants.

Duskie says she frequently loses her small hog ranchers who have pigs on pasture; they find it challenging to pasture-raise their hogs because few consumers are willing to pay the price for the end product. Duskie also keeps losing co-packers who are willing to use her lengthy dry cure method. She is constantly looking for suppliers (hog farms and meat processors) who will meet her specifications (of sustainable production practices and pricing). If she could surmount the barriers, she would buy more from small- and mid-scale farms.

Another challenge of working with small farms and processors is the regulatory environment. Duskie says that the USDA regulations currently give preference to large farms, especially with regard to food safety. The cost of meeting all of the regulations is difficult for smaller-scale farmers and processors alike.

3.1.4. Pricing

Putting the time and care into bacon and salumi processing is costly. In fact, Duskie says that their meat is four to five times more expensive than commodity products. For a 12-ounce package of bacon, she charges $13 to $14 locally, and $18 in East Bay stores to cover the costs of the processes necessary to change the way animals are raised in the US and to ensure the viability of small pork producers. Her first priority is choosing producers who give their hogs access to pasture. She tries not to “beat down farmers on price” but she does want them to meet the price she can get from another similar producer.

The average dinner meal at Zazu is about $39 currently, including drinks and tax. It should be closer to $60 if Duskie were to pay everyone (farmer, pork producer, etc.) the way she would like. However, she does nor think customers would be willing to pay that much.

To help make their whole business viable, Duskie and John also produce pork-based value-added products which they sell at the restaurant, such as “swine sweets” (peanut butter cups with fried pork belly or pork fat), “rodeo jax bacon caramel corn”, and “bacon piggy pops”. These novelty products also use other parts of the whole pig and promote the Black Pig Meat brand.

3.2. Capay Valley Farm Shop (Thomas Nelson, President/General Manager, Esparto, California)

Capay Valley Farm Shop (CVFS) is a food hub that operates both a community supported agriculture (CSA)-style subscription program for consumers and a wholesale aggregation/distribution business targeted at corporate cafeterias, restaurants, online grocers, and a few specialty food markets in San Francisco and the South Bay Area (primarily the Silicon Valley). Its revenues in 2015 totaled just over $700,000, with 80 percent generated from the wholesale business. Thomas Nelson serves as the firm’s president and General Manager. He has existing relationships with many producers in the small Capay Valley community in western Yolo County where he is a long-time resident.

CVFS is marketing products from 54 family farms that are all located in western Yolo County, except for one farm that grows rice in a neighboring county. Since rice is not perishable, this farm delivers to CVFS about once a month. When CVFS was founded in 2007, it was a retail operation; it has since transitioned into other market channels. It began selling wholesale in 2011. It is currently phasing out its CSA-style program because of intense competition among online local food delivery services. CVFS expects to grow its wholesale business, and will add a limited offering of grower services (such as deliveries), which Thomas expects will generate about 2% of its overall revenues in 2016. About fifty percent of CVFS’s wholesale revenues are generated from sales to restaurants and corporate cafeterias, forty percent from sales to online grocers, and about 10% from sales to specialty retailers. Neither CVFS’s customers nor its farms have formal contracts with CVFS.

Most of the original 27 farms that were CVFS suppliers in 2007 are still marketing through CVFS. The food hub handles a wide variety of fresh fruits and vegetables, pasture-raised meats, eggs, and value-added products—including dried herbs, flour, rice, legumes, jams, honey, nuts, olive oil and handmade lavender beauty care products. CVFS has a co-branding program with Capay Valley Vision, a local noprofit organization created to preserve the valley’s heritage, natural resources and farmland, and enhance its community health and economic well-being [

25]. Capay Valley Vision operates a promotion program for local farms called Capay Valley Grown [

26].

3.2.1. The Logistics Behind CVFS

Some CVFS members were already familiar with the logistics of operating a food hub. During the 1980s, they founded a cooperative food hub called YoCal in their community in order to have produce delivery services into the San Francisco Bay Area [

27]. Although YoCal was not as well-operated as CVFS, it enabled many of the members to expand their farms and sales considerably. Currently, CVFS is making deliveries three days a week. Typically, the food hub’s farms email or phone CVFS at least once a week to identify what products they have available. CVFS sends out an availability list to its customers, and receives their orders (usually by email) the following day. CVFS then relays the order information to each farm. On the following day, a CVFS truck picks up most of the products being ordered and brings them to the warehouse in Esparto to be sorted and consolidated with other items being delivered to each customer. Meat cuts are usually processed at the small USDA-inspected meat plant that is in the same building with CVFS.

3.2.2. Transparency/Communication about Values

Thomas knows the production practices of all the CVFS farms; it is vital that each farm provides high quality product through CVFS. He understands the importance of sharing customer feedback—both good and bad—with a specific farm. He also brings CVFS producers together annually to discuss CVFS’s overall successes and challenges. Last year, an additional meeting was held to examine the complications created by the drought in California. When assessing a farm as a new CVFS supplier, he inquires about its products and production practices, which are the attributes that CVFS’s customers are most interested in. Customers want to know if the product is organic, and if not, what is different about it (such as pasture-raised for meats and eggs). Thomas considers farm identity to hold more resonance in the long term, since organic production can be industrial-scale.

Thomas believes that cultivating strong relationships with customers is also very important to CVFS’ success. He has not yet developed a regular farm visit program for CVFS customers, but he recognizes that farm visits could be a critical tool to building strong relationships. He usually visits each new wholesale customer, and shares information about the small Capay Valley farming community and the CVFS farms’ values and production practices. He noted that if the customer does not share CVFS’s values and is very price-sensitive, the relationship will not work out.

When CVFS runs short of a product, it contacts the CVFS farms to determine if they have more of the product. If not, the customer(s) will be advised about the shortage. CVFS does not bring in products from other wholesalers because their product is not likely to be from the Capay Valley.

CVFS reinforces its values and brand identity through its everyday practices. Its trucks have the CVFS logo visible prominently on their doors. When the food hub sends its availability list to its wholesale customers, the farm is identified for each product, along with descriptors such as organic or pasture-raised. The products are shipped in standardized boxes identifying the farm and the product. CVFS’s invoices include the farm identity of each product sold.

Certain CVFS customers, such as the on-line produce delivery supplier Good Eggs, always identify the farm on their products as part of their corporate strategy. Other customers only identify the Capay Valley farms occasionally. Cafeterias at the Silicon Valley companies do not appear to identify the farms producing the produce and meats they serve.

For its CSA program, CVFS has been emailing a weekly newsletter to its CSA customers that identifies the farm for each product in the CSA box. The newsletter usually features a profile of one of its network of 54 farms. The profiles are then posted on CVFS’ website, along with a link to the farm’s website (if it has one).

3.2.3. Sourcing from Small and Mid-Scale Farms

There is considerable size diversity among the farms that supply CVFS. Most of them are small (with less than $250,000 in gross annual revenues), some are mid-sized, and a few are large (with gross annual revenues of at least $1 million). Since many of the CVFS farms grow some of the same crops, CVFS typically includes only the farm with the lowest price on its availability list. However, it will list two farms selling a product (such as heirloom tomatoes) with different prices during peak availability periods. Two farms are also included on CVFS’ availability list when some customers have strong preferences for a specific farm.

Thomas advises the CVFS producers to market through multiple channels and to not rely exclusively on CVFS for their sales. He also informs newer CVFS producers about customers’ expectations and requirements, particularly regarding packing standards (such as sorting crops by size and appropriate box sizes), proper postharvest handling of their crops, and food safety practices, including the soon-to-be-implemented Food Safety Modernization Act. Similarly, Thomas will often walk newer producers through an assessment of their production costs. He recognizes that CVFS’s viability depends on the farms being financially sustainable.

Thomas has begun conducting some crop planning with specific farms, in order to ensure a better match between specific customers’ needs and the farms’ production. He noted that CVFS is “… actively open to working with all local farms that are a good fit with [its] customers’ needs. In terms of products, it is always great to diversify the offering”. He identified dry beans, more fresh fruit such as kiwis, and meats as welcome additions to CVFS’s product list.

3.2.4. Pricing

Each farm sets its own prices. Thomas informs a producer if he thinks the price is too high, which the producer adjusts. Conversely, Thomas sometimes tells a producer “you can get more” and the producer usually raises the price; he wants to avoid price-cutting among the farms.

CVFS’s prices to its customers usually reflect a 30 percent margin to cover its costs. If a particular product has a high price (such as meats), Thomas will cap the margin contribution per sale to $15 or a similar value.

Thomas noted that the wholesale produce business is very competitive, even for organic crops. There are many large-scale organic farms in California; most CVFS farms lack the economies of size to compete with them. Additionally, CVFS is a small business and it cannot compete with large distributors, such as Sysco which operates with a 12 percent margin. Therefore, CVFS must differentiate itself through its values, and promote its farms’ brand identities. This effort requires constant education by the food hub. Chefs and other buyers need to be educated about the CVFS farms and the more costly practices they engage in to produce organic crops, pasture-raised or free-range poultry. Thomas believes that the recently passed legislation to increase California’s minimum wage by 50% to $15 per hour will be challenging to the farms, CVFS, and other small rural businesses, particularly when the same crops can be sourced at lower price from other states or Mexico.

3.3. Sacramento Natural Foods Co-op Produce Supply Chain (Kerri Williams (KW)-Produce Manager and Paul Cultrera- General Manager, Sacramento, California and Bu Nygrens (BN)-Co-Owner, Veritable Vegetable, San Francisco, California)

Sacramento Natural Foods Co-op (SNFC) is a member-owned grocery cooperative store founded in 1973, near downtown Sacramento, California. With sales of $33 million in 2015, it is the largest single-store grocery cooperative in California. Sometime this fall, SNFC expects to move into a larger store (42,000 square feet) that is being built. It carries a full line of grocery products, including meat, produce, deli items, shelf-stable foods, health and beauty products and cleaning products.

For over forty years, SNFC has been owned by thousands of members of the community. Consumers become members of SNFC because they share its values which are: (1) cooperation; (2) sustainable practices; (3) support for healthy choices; (4) belief in cooperative economics; and (5) open, honest and trustworthy business practices [

28].

With the largest 100 percent organic produce section in the United States, SNFC buys about 30% of its produce direct from local farmers. However, most of its produce has been supplied since 1978 by a San Francisco-based organic produce distributor, Veritable Vegetable (VV). VV supplies organic produce from over 600 farms primarily to grocery stores, and some restaurants, corporate campuses, juice cafes, and schools throughout California, and parts of the southwestern US and Hawaii. VV’s revenues have grown from $45,000 in 1975 to over $50 million in 2015.

As a national leader in the organic produce industry, VV has contributed to the development of organic certification standards and composting practices, and has advocated for sustainable food and agriculture legislation. VV’s core values are integrity, community, excellence, innovation and sustainability [

29].

All but one of SNFC’s core values listed above (belief in cooperative economics) are reflected in its produce sourcing and promotion practices. It is likely that the longevity of SNFC’s relationship with VV is largely attributable to their shared core values and the similarity in the business practices—particularly those related to transparency in communicating their values, sourcing from small- and mid-scale producers, and paying fair prices to producers.

3.3.1. Transparency/Communication about Values

SNFC actively supports its core values to differentiate itself from other stores in the Sacramento region. Its produce department’s commitment statement describes three of SNFC’s values—cooperation, support for healthy choices, and sustainable practices: “Sacramento Natural Foods Co-op is part of a larger food community that includes farmers, wholesalers, manufacturers, shoppers and the Earth. We purchase only the highest quality certified organically grown produce and emphasize direct buying relationships with local small family farms”.

VV’s values of integrity and community are related to transparency. Its value of integrity is exemplified through its founding principles of collaboration, cooperation and interconnectedness and belief in cultivating and nourishing long-term relationships with vendors. As a founder of the US organic industry, VV worked with many struggling growers to distribute their produce, promote sustainable farming practices and policies, and extend knowledge about organic food and agricultural issues. Its commitment to sustainability also includes operating a “green fleet” of hybrid tractors and trailers to handle and transport produce to its customers. BN, one of VV’s owners, admits that although VV does not know specifically about the core values of the farms it sources from, “we tend to buy from people we know and trust”. There are dozens of farms that she can identify as being suppliers to VV for twenty years or more.

VV does not have written contracts with any of the farms that are its suppliers; instead, VV tries to be consistent and reliable in its purchasing practices. As a testament of its value “open, honest and trustworthy business practices”, SNFC similarly does not have written contracts with any of the farms or distributors from whom it buys produce. If there are problems with the delivery, KW, SNFC’s Produce Manager, will contact the grower or distributor immediately. Similarly, if VV receives poor quality product, it rejects the delivery and promptly informs the grower.

Local growers (within 200 miles of the store) that SNFC buys from deliver their produce to the store. Additionally, KW makes a special effort to order produce that is local from VV. She estimates that at least 80 percent of the farms providing produce to SNFC through VV are local. SNFC identifies the farm and its location for every produce item on display. SNFC’s Produce Manager noted that she and her staff have a personal relationship with each of the local growers. Its website’s produce page has links to the websites of the local growers who sell direct to SNFC.

VV’s availability list has been source-identified since 1979. VV sends a customized product availability sheet daily to SNFC. A typical list has about 750 items; each item is identified by variety, size/grade, pack type, price, certifier, and grower label. When ordering online, customers can utilize filters to sort by farm name, produce item, distance from VV’s warehouse (such as 150, 250 or 400 miles), and Fair Trade Items. Customers also have the option to order by farm name.

3.3.2. Sourcing from Small- and Mid-Scale Producers

SNFC buys about one-third of its produce direct from small- and mid-scale farms. Its Produce Director intentionally spreads her purchases among smaller growers, and she gets a couple of new growers each year.

Similar to SNFC, VV strives to spread its business around to support the long-term financial viability of the growers who it works with. It offers multiple grower labels for multiple produce categories. Currently, VV is actively trying to match its mid-scale farm suppliers with independent grocers, because they have smaller volume requirements. VV rarely buys produce from small-scale growers because their product volumes are not usually enough to meet most customers’ order quantities. In addition, carrying a large variety of labels creates logistical issues for VV.

Food safety is becoming a major concern for VV even though it is certified by USDA for Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs) and Good Handling Practices. BN is concerned that the implementation of the national Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) will cause VV to lose some of its customers and/or some of its farm suppliers, particularly the smaller ones. She remarked that VV is “… increasingly hampered by certain customers who only want product from GAP certified farms, and if there are farms we work with that do not have GAPs then we can’t sell to those customers. This [problem] will be increasing, and is already an added expense to us for managing our vendors, and their products”.

SNFC’s Produce Manager admits that it can be challenging sometimes for SNFC to get smaller farm operators to understand there are differences in the requirements of produce sold at the co-op compared to farmers markets. For example, SNFC is not able to display product that is overly large or misshapen. However, she is always encouraging newer farms to grow unusual crops, such as finger limes, salsify and other unique herbs.

3.3.3. Paying Fair Prices to Producers

SNFC’s Produce Department has a gross margin rate target of 33.75 percent. KW noted that the Co-op is committed to paying our growers a fair wage …” She said that “Cheapest is not usually the best quality”. It will pay premium prices for certain well-known farm labels, including some which are delivered direct. Nevertheless, SNFC is able to claim that its organic produce is almost always priced lower than the same item at other natural food markets in the area.

VV averaged a gross margin rate of 32 percent in 2015. It does not regularly give smaller-scale farms a premium price. BN remarked “We readily share market price information with growers ... But there are situations when VV will pay a premium price for a specific label and then take a lower mark-up for a product” [

30]. Additionally, some VV customers will pay premium prices for certain labels.

4. Discussion

As we have discussed elsewhere [

21], these VBSCs cannot be characterized by neat, linear relationships. Rather, they are more like networks that interact with each other and with conventional supply chains in complex ways.

Figure 1 shows the key partners in each of the three cases representing different points along the supply chain, and each case involves several marketing channels for small and mid-scale producers to move their products through VBSCs. What distinguishes the particular supply chains in our cases is that they strive to uphold and communicate a set of social and environmental values that prioritize quality, cooperation, inclusiveness, equity, sustainability and health. As previously noted, the “values” in VBSCs may be that the products are produced by small- or mid-scale farms, are locally/regionally produced, and/or the farms and/or ranches use production practices that enhance the environment and/or worker welfare. Profitability is also important; rather than standing alone, it is connected to the social and environmental values.

Rather than relying on market transactions, these VBSCs represent long-term relationships among firms with shared values committed to the long-term sustainability of all of the partners in the supply chain. The buyers and farmers socialize at local events, as well as reconnecting at an annual farm conference. They can be considered to be socially overlaid networks [

31].

Each of the three VBSC cases faces unique, yet similar challenges. Similar to Mikkola’s analysis [

31] of three different vegetable supply chains, we found distinct differences but also overall similarities in challenges on the chain level. In this section, we highlight the key challenges faced by supply chain partners and some innovative ways they are managing to overcome some of these challenges. We make cross-cutting comparisons of the strengths and challenges displayed by each of the three cases related to three key VBSC characteristics:

transparency/communication about values,

sourcing from small and mid-scale producers and

fair pricing practices. Our discussion is summarized in

Table 1.

4.1. Transparency/Communication about Values

The partners in all three cases have made a supreme effort to be transparent about who they buy from (farmers/ranchers), particularly when the relationships are direct. Information about the producers’ values must flow through each link along the supply chain in order for producers to be paid fairly.

In our cases, suppliers identify the farms with their locations on their availability lists and their shipping cartons, and they include the farms’ names on their invoices. They profile farms in newsletters for their customers. However, the distributor sometimes has difficulties obtaining information from a farm about its values. In addition, information and feedback are shared up and down the supply chain to improve the efficiency or quality of the business relationships. Managers share feedback from customers and buyers, and internally with staff. The retailer holds a monthly luncheon with a grower for its staff to become more familiar with the farms. In each case, the type of communication is similar to “socially overlaid networks” described by Mikkola [

31] in which actors knew each other from local contexts and had a common history as opposed to the “strategic networks” described by Jarillo [

32]. In addition to sharing information and values

within these supply chains, the partners also share their values by being involved in broader agricultural and culinary communities.

Written forms of communication are most common for sharing information with consumers. Farms are identified on restaurant menus and the retailer’s produce displays (along with locations). Farms are profiled on websites. The restaurant and retailer also employ innovative forms of communication involving one-on-one human interaction, such as “pig tastings” to educate consumers about the importance of using the whole animal. The retailer hosts “Meet the Farmer” events for its shoppers and sponsors on-farm events organized by local culinary organizations.

Communication is a very high priority for all of our cases because being part of a VBSC means that values must be communicated throughout the supply chain. However, the process of continually educating consumers about the higher prices they are paying for the values embedded in the foods that they are being served or buying can be costly and time consuming. In some cases, a website cannot convey information about values as effectively as visiting a farm and talking with the farmer about his or her production practices. Nevertheless, this consumer education process is inherently easier when the retailer is a cooperative with consumer members. As discussed by Hingley et al. [

33], consumer food cooperatives are ideally suited to participate in VBSCs because their members have already committed to supporting environmental sustainability and responsible and ethical behavior, as well as being experienced in “… combining business and social/community networks”(p. 352).

However, there can be logistical challenges conveying information along multiple links in a supply chain. For example, it is difficult for the restaurant to identify the source on an ingredient when multiple producers and processors are involved. Workplace cafes in the Silicon Valley do not identify the CVFS farms supplying the ingredients in the artisanal dishes they prepare.

Receiving a premium for products (fresh produce, meat, or other product) requires a high degree of integrity to maintain trust between supply chain partners. However, in her thesis regarding the benefits of farm-identified produce in Bay Area grocery stores, Lerman found [

34] that perceptions about the extent of these benefits differed between farmers and buyers, and specific contexts mattered. The challenges included: building inter-organizational trust beyond interpersonal relationships; dealing with the volatility of the marketplace; and maintaining authenticity in values claims. Our three VBSCs have experienced instances where buyers have taken advantage of well-known farm names, using them in advertising to obtain more business, when, in fact, they may only have purchased from the farm once or twice. Such malfeasance is likely to destroy socially overlaid networks, but is likely to be tolerated in a market or network relationship for reasons of efficacy. All of the VBSC partners know how important integrity and honesty are in creating authentic relationships with customers or suppliers.

4.2. Sourcing from Small and Mid-Scale Farms

These VBSC cases promote sourcing products from small and mid-scale producers to help them stay financially viable. Food retail cooperatives in the US have a long-established commitment to sustainability, including supporting small- and mid-scale farms [

35,

36,

37]. The SNFC cooperative has a duplex produce supply structure; while VV is its primary supplier, SNFC also sources direct from local farms and regularly adds new farm suppliers. Both the cooperative and the distributor spread their purchases among several smaller growers instead of buying from just one or two, so that everyone has some sales. The majority of producers involved in CVFS are small and mid-scale farms. This food hub is even guiding the producers in assessing their production costs. The restaurant (Black Pig/Zazu) buys the whole animal instead of just the most popular parts because it is difficult for small- and mid-scale farmers to sell certain cuts. Additionally, both the cooperative and the food hub have taken on didactic roles, coaching newer farmers in understanding buyer requirements, such as what type of product is acceptable, packing standards, postharvest handling and food safety. These interactions have long histories and are similar to the socially overlaid networks described by Mikkola [

31].

One of the primary challenges of sourcing from small and mid-scale farms is volume requirements. Given the large size of its business, the distributor often utilizes a network relationship structure in order to operate in an effective and efficieint manner. Since the administrative costs to source from small-scale farms are higher, it does not do business with them. However, it is focusing on matching its mid-scale farm suppliers with its independent retailer customers.

Regulatory constraints, including food safety, have been a challenge for producers for a long time. The USDA’s meat processing regulations have reduced the number of facilities in California that will process livestock for smaller-scale ranchers; this constrains the supply of sustainably-raised hogs. The restaurant has addressed this challenge by vertically integrating upstream; it closes its restaurant once a week to become a meat processing plant, and it also produces snack foods from the byproducts. However, the regulations prohibit wholesaling the processed meat products; they can only be served or sold at the restaurant.

The biggest challenge on the horizon related to sourcing from small- and mid-scale producers appears to be compliance with food safety requirements. The first difficulty is that it has become a standard business practice for produce distributors, restaurants and grocery retailers to carry product liability insurance because they could face bankruptcy if they are involved in a food safety outbreak. The insurance companies are requiring their policyholders to only use food suppliers that are audited and certified by a specific food safety certification company. Secondly, the compliance costs associated with the soon-to-be-implemented regulations for the federal Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) are likely to threaten participation of some small and mid-scale farms in these supply chains. It may be more profitable for them to stop selling wholesale to reduce their annual sales to less than $500,000, which would then exempt them from most of the FSMA’s requirements.

4.3. Fair Pricing for Farmers

In market relations, farmers are considered to be interchangeable suppliers; if one farmer goes out of business, a buyer can find another farmer to supply the same commodity. In a VBSC, the farmer is valued for his or her production practices, and is considered to be an equal partner in the supply chain. The VBSC partners are committed to the long-term sustainability of all of the partners.

All three cases are willing to pay farmers a fair price, or as much as they can afford. They cannot always pay a premium to the smallest producers (VV), but they expect to pay their values-based producers what similar producers are making in these values-based markets. They are willing to reduce their own margins sometimes to help out small growers. They are able to offer fair prices because they have distinguished themselves as VBSCs in the marketplace and their customers are also willing to pay more (marginally).

Through their transparency, the VBSC partners have helped the farmers establish their “brand identities” with consumers—their farms’ names—which differentiate them by representing the farms’ values. Both VV and SNFC will pay premium prices for certain well-known farm brands, including some farms that deliver direct to SNFC.

Unlike most food retailers, consumer-owned cooperatives in the US are part of socially-embedded networks. They have a long-established commitment to sustainability, including supporting small- and mid-scale farms by paying them fair prices [

36]. Unlike shareholders of grocery companies with publicly traded stock, members of consumer cooperatives do not have expectations of high returns and have more flexibility with pricing. They are satisfied as long as their co-op fulfills its social and environmental missions, while adding a small increase to its financial reserves each year.

Lerman [

34] found that VBSCs can be challenged by tradeoffs between consumers’ expectations about prices and what prices farmers need. She noted “Product differentiation and consumers’ willingness to pay is a significant factor in determining the price for products sold not only through VBSCs but in any market. A growing number of consumers recognize the value in supporting farmers growing products embedded with particular values and will pay a price premium for those values”(p. 86). However, she concluded that much more consumer education is needed about the values. US consumers are still price-sensitive when purchasing food because the globalized and highly industrialized food system has been providing them with “cheap” food.

Information about the producers’ values must flow through each link along the supply chain in order for the producer to be paid fairly. The key challenge on pricing is negotiating a price that works for everyone. Sometimes farmers get less than they would like; other times, buyers get less. As long as all parties feel that their best interests are considered, sales will continue. The bottom line is that partners throughout these supply chains trust the others to be as fair as possible. This level of authenticity requires constant communication and is intricately linked to the transparency discussed earlier.

5. Conclusions

Although the experiences of these three case studies are not necessarily generalizable to other VBSCs, the case descriptions and the cross-case comparisons in the preceding discussion give us deeper insight into how VBSCs are working and the challenges they face. They also provide insights about the potential viability of VBSCs as a relatively new organizational structure for developing regional food systems.

In the last decade, much has been accomplished to expand and strengthen these VBSCs, but many VBSCs are still tenuous financially. As SNFC’s relationship with VV approaches forty years, it is clear that its durability is largely attributable to how closely their values are aligned. We expect more such success stories as newer VBSCs mature.

Food hubs and values-based produce distributors—such as VV—can and do support “Agriculture of the Middle” farmers and ranchers in accessing local markets. The number of food hubs in the U.S. has increased markedly the last five years. CVFS and other food hubs are working with smaller-scale growers to improve the growers’ production efficiency. By aggregating product, the food hubs are also reducing distribution costs. Such economies of size are critical when consumers are prone to comparing prices. However, food hubs face many challenges, including capitalization, liability issues, compliance with food safety regulations and managing human resources [

38]. However, the potential role for food hubs within VBSCs and their impacts on producers and others may be promising. More study is needed to understand these challenges and how they can be addressed.

The partners in all three cases would like to find ways to make changes to the larger food system regarding food safety requirements and regulations, investment in mid-scale infrastructure, and higher level of consumer awareness—so they can be more competitive in the marketplace. Research is needed to measure the costs—particularly for small- and mid-scale farms—to comply with their customers’ food safety certification requirements and the new FSMA regulations. The number of smaller-scale farms in the US that decide to “downsize” in order to become exempt from most FSMA regulations should also be monitored. Some funding is currently available to conduct feasibility studies for building mid-scale infrastructure, such as processing facilities. However, policymakers need to be shown how such investments can have significant economic development impacts by localizing their region’s food supply. Such support could then entice the creation of state and/federal government programs to finance mid-scale infrastructure through the formation of community development districts, as well as providing tax credits and other incentives for local private investment.

Perhaps the most important issue is whether and how VBSCs can enhance their communication about their values and build demand for their values-based products. More retailers are needed to participate in VBSCs. They will join in if their customers demand more value-based products and are willing to pay for them. Therefore, transparency both within the supply chain and within the larger communities of which they are a part (agriculture, distribution, culinary) needs to be expanded. Although the chef community is now fairly conversant with the “farm to fork” theme, most consumers are still unaware of where their food comes from or the values it carries. They need to understand the true cost of their food. Starting with the youth, considerable effort is needed to educate consumers about the connections between the health of the environment, the economy, the community, and their own health. Building strategic alliances outside these immediate supply chains to programs such as “Farm to School”, “Farm to Hospital”, corporate or institutional wellness programs, ready-to-cook meal kit programs, urban gardens and farms, and community health events, could go far in expanding the understanding and commitment of the public to a more sustainable food system. Such programs should include rigorous evaluation components, in order to identify the most long-term cost-effective education structures.