Experimental and Theoretical Study on the Heat Transfer Coefficients of Building External Surfaces in the Tropical Island Region

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

- (a)

- For CHTC, field measurements based on a naphthalene sublimation experiment were conducted in the tropical island region.

- (b)

- By combing the RHTC calculation theory with the annual average temperature in Xisha, the RHTC in the tropical island region was determined.

- (c)

- By considering the difficult point that the occurrence of rainfall and evaporation heat transfer does not exactly correspond in real time, a simplified calculation model of daily average EHTC was put forward.

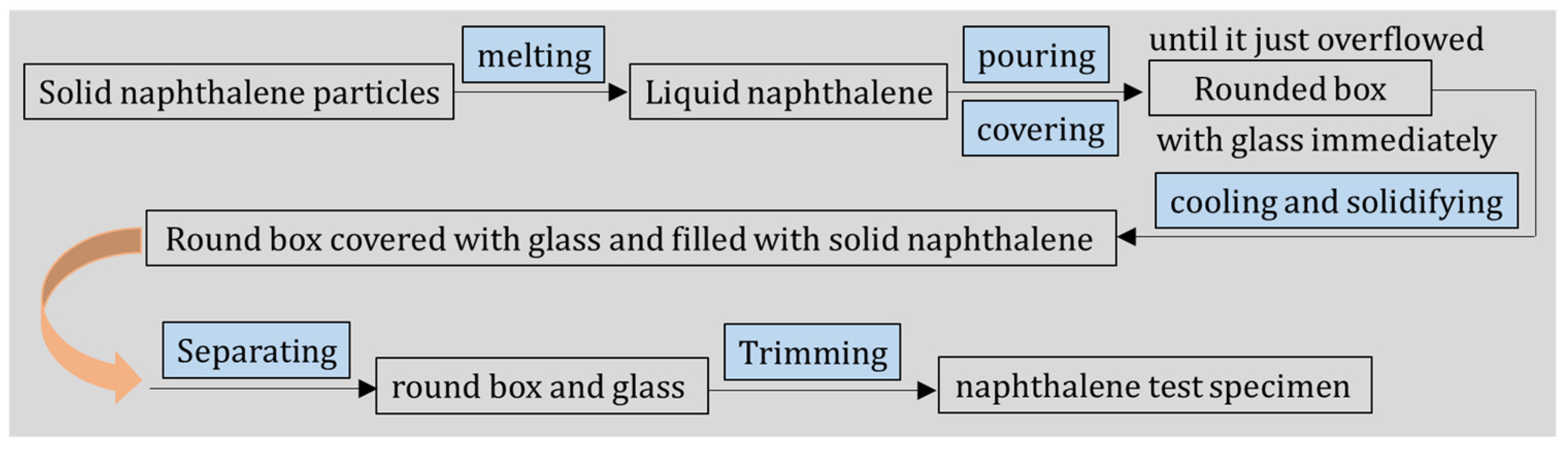

2.1. Naphthalene Sublimation Experiment

2.1.1. Experiment Principle

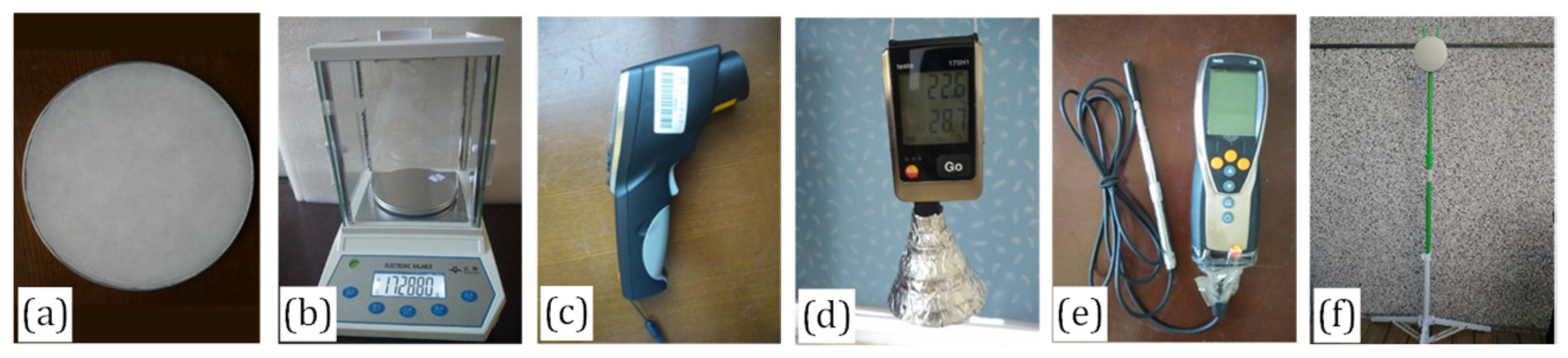

2.1.2. Experiment Instruments or Devices

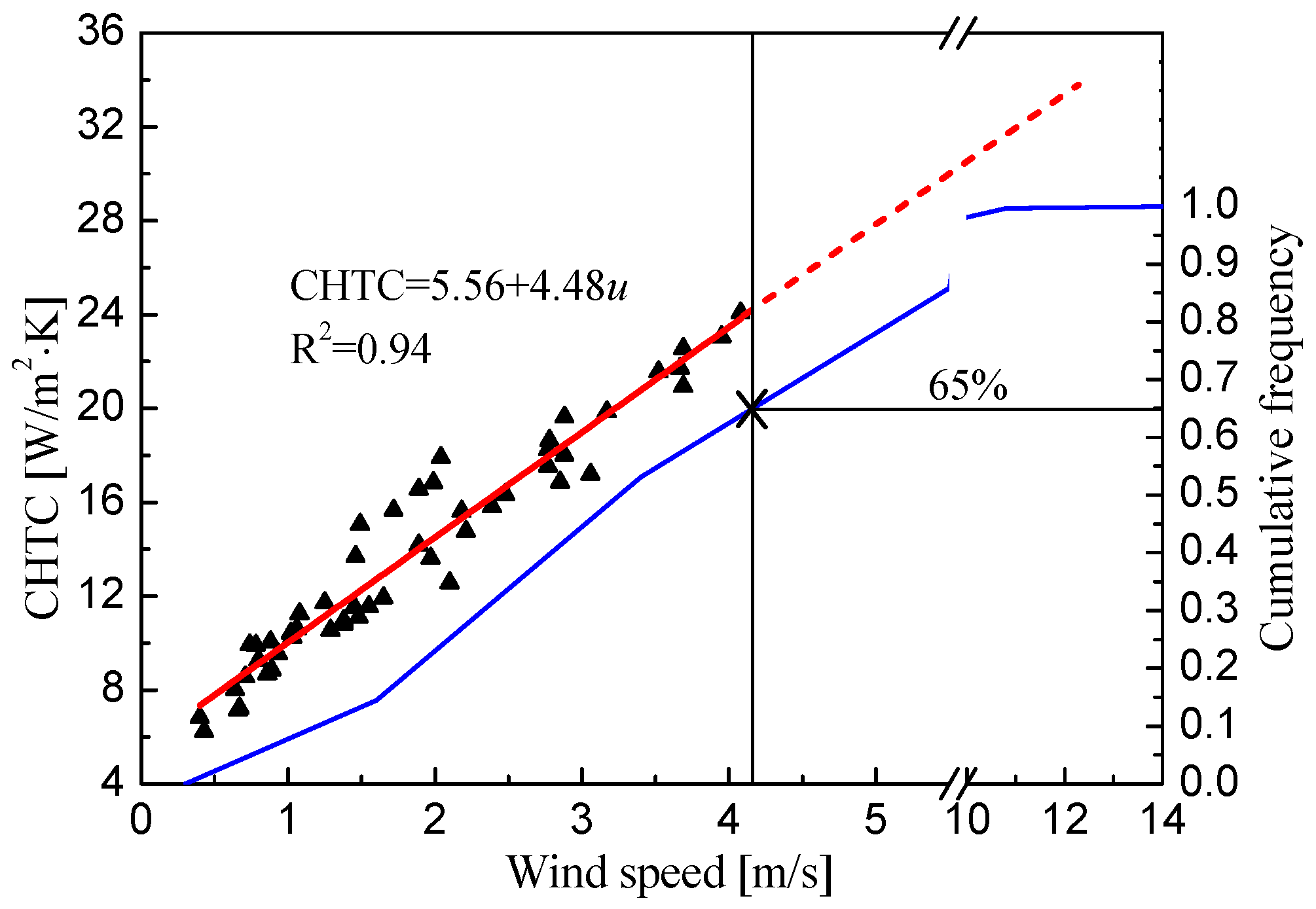

2.1.3. Experiment Steps

2.2. RHTC Calculation Theory

2.3. EHTC Simplified Calculation Model

2.3.1. Calculation Principle

2.3.2. Simplified Processing Method

3. Results

3.1. Naphthalene Sublimation Experiment

3.1.1. Test Subject and Weather Conditions

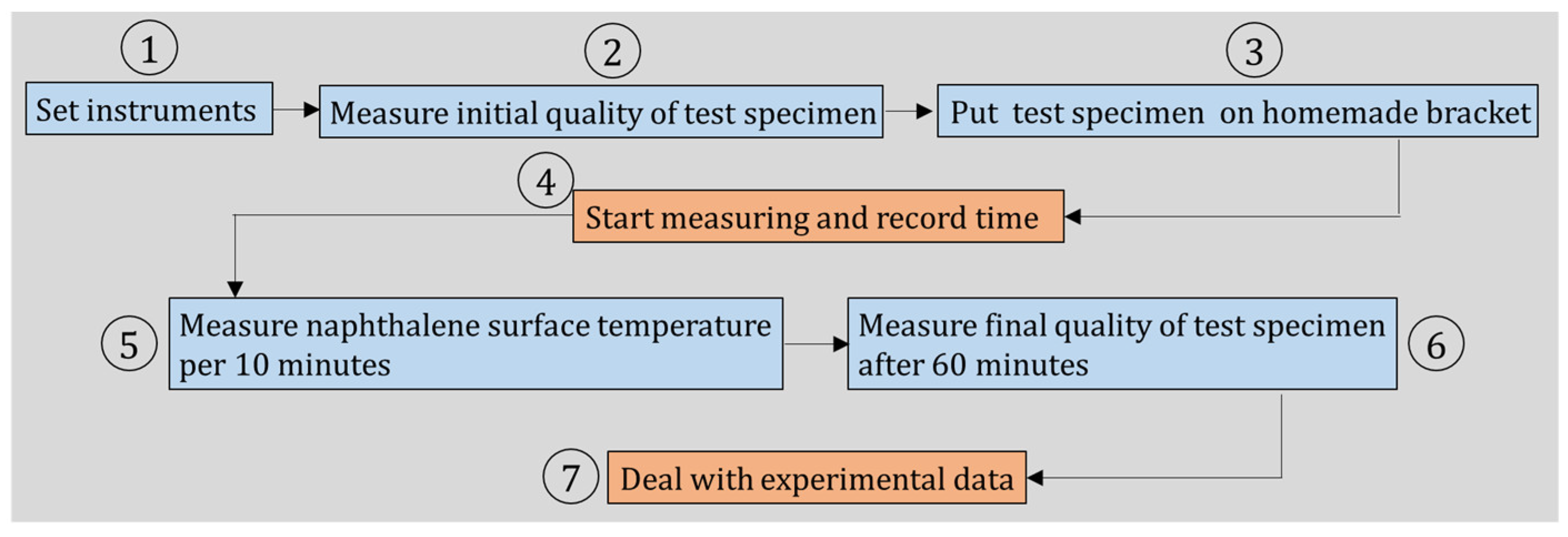

3.1.2. Relationship between CHTC and Wind Speed

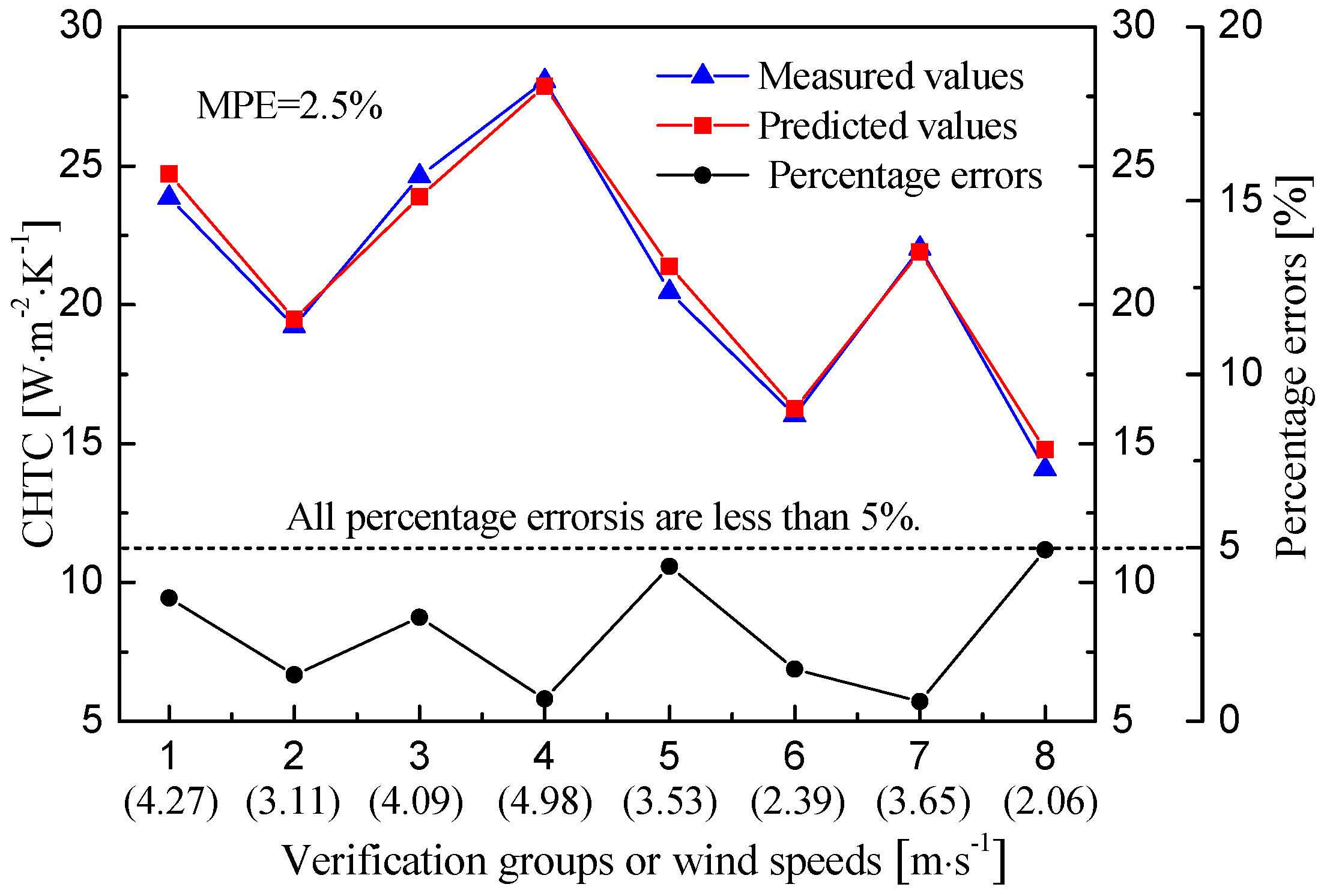

3.1.3. Verification of CHTC Predictive Model

3.1.4. Uncertainty Analysis of the Naphthalene Sublimation Method

3.2. Features of Wind and Rain in the Tropical Island Region

3.3. Heat Transfer Coefficient in the Tropical Island Region

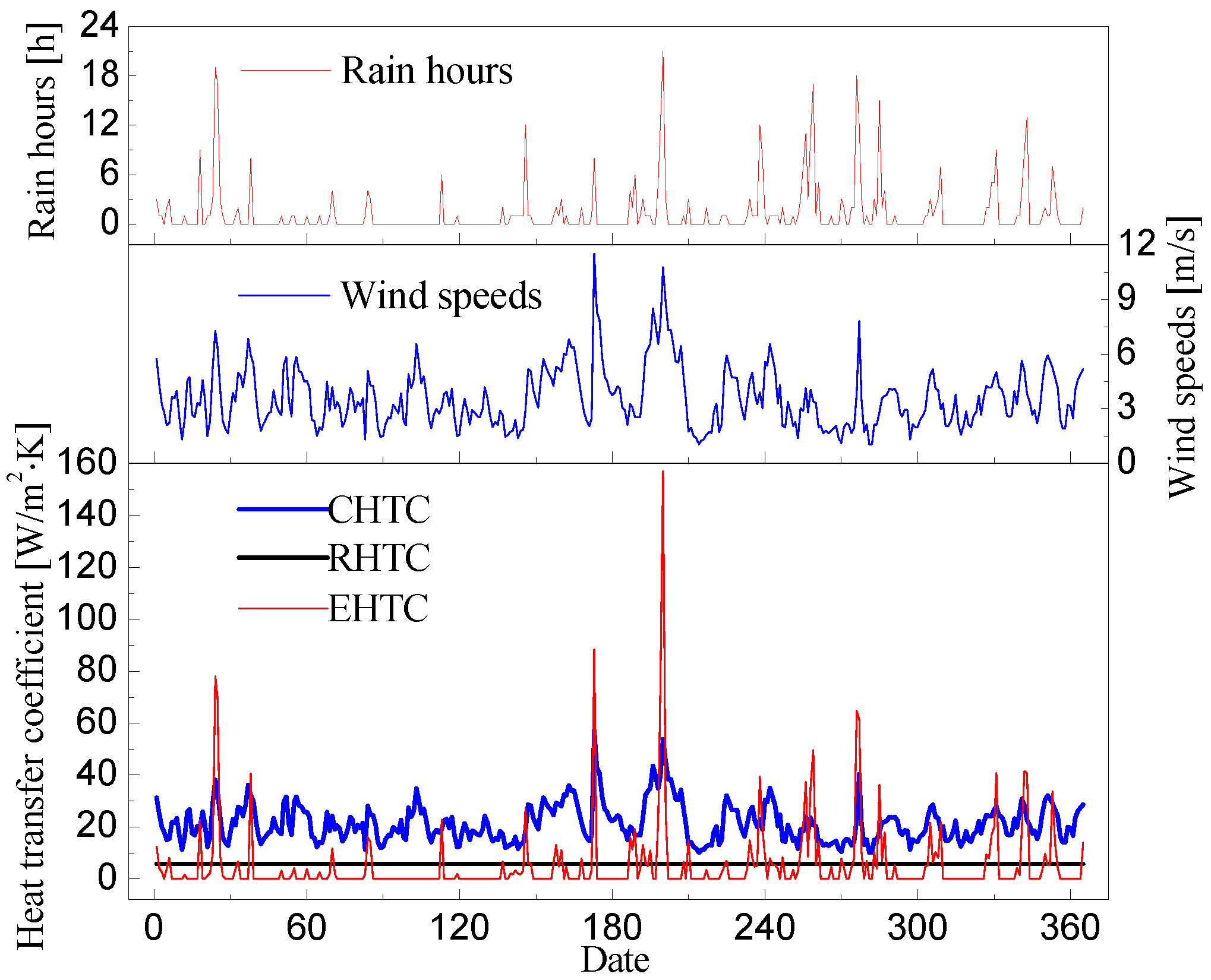

3.3.1. Daily Average Heat Transfer Coefficient

Relation between Heat Transfer Coefficients, Wind Speeds, and Rain Hours

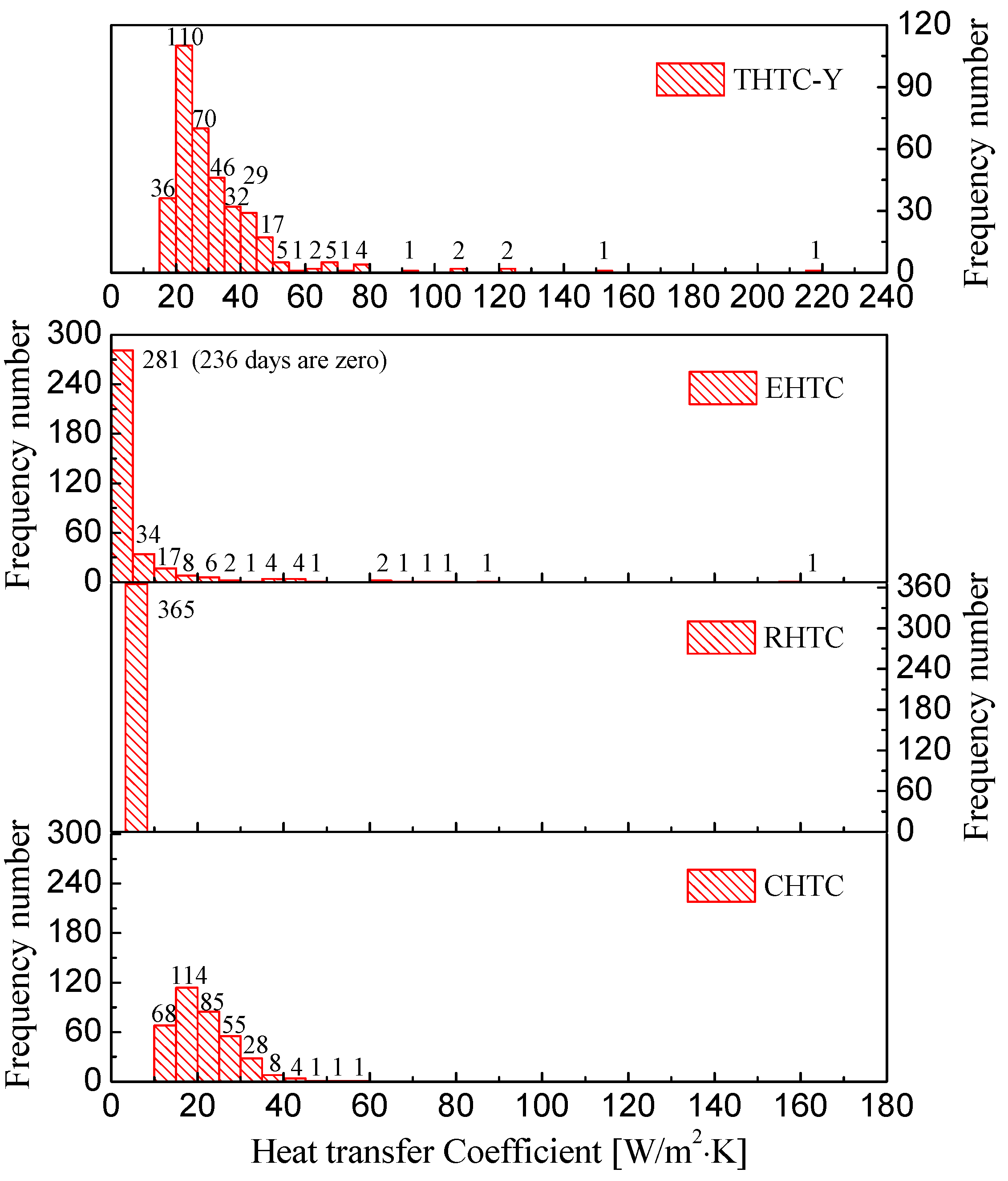

Frequency Distribution of Daily Average Heat Transfer Coefficients

3.3.2. Monthly Average Heat Transfer Coefficient

- (a)

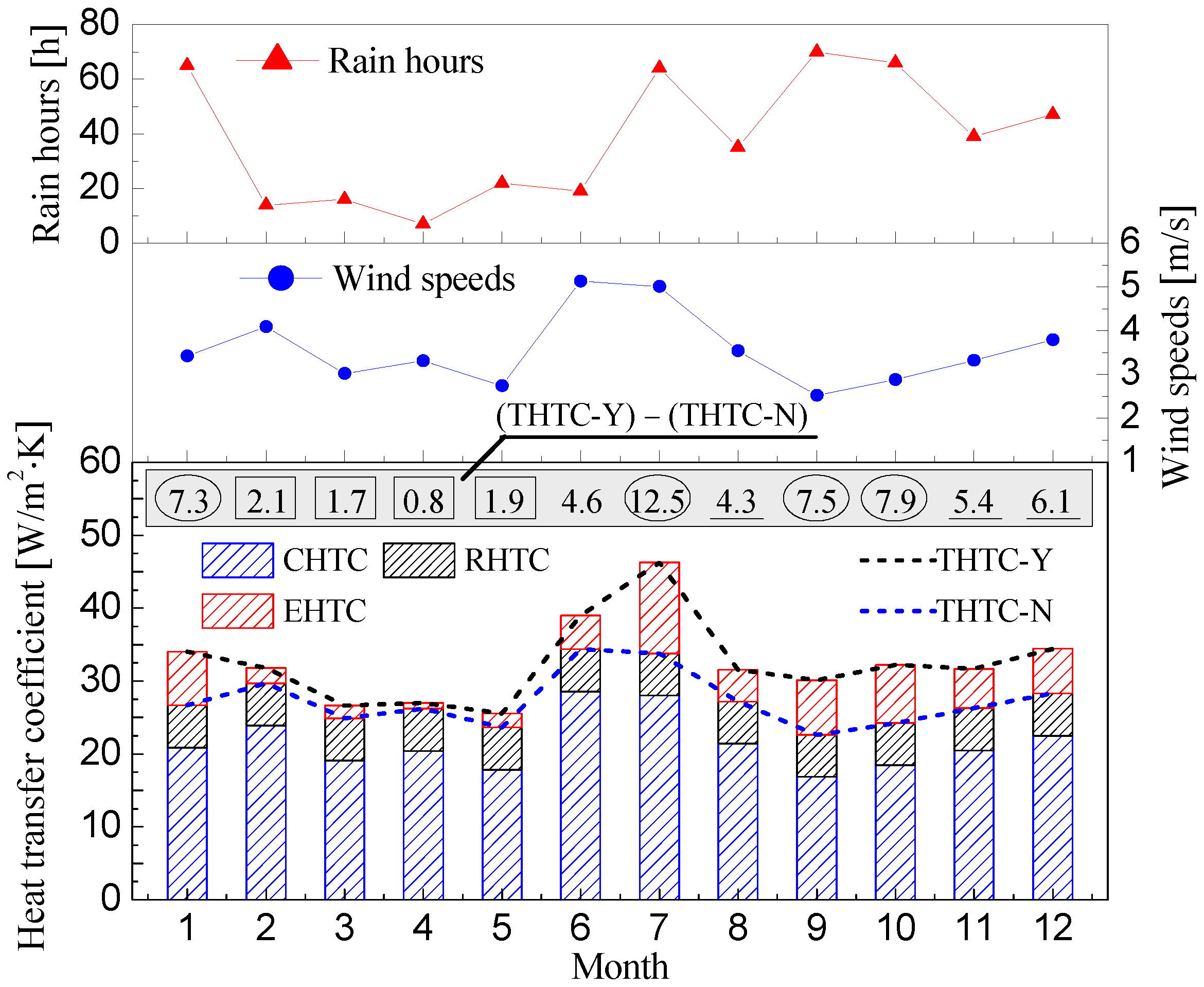

- The differences between THTC-Y and THTC-N are large in January, July, September, and October with climate features of high wind speeds and strong rainfall, or relatively low wind speeds and especially frequent rainfall. For July particularly, EHTC reaches up to 12.5 W/(m2·K) under the combined action of high wind speeds and strong rainfall.

- (b)

- The differences between THTC-Y and THTC-N are small from February to May, as these months possess relatively low or medium wind speeds and very few total rain hours. The EHTCs in these several months are all less than 2.5 W/(m2·K) (only 0.8 W/(m2·K) for April).

- (c)

- The differences between THTC-Y and THTC-N are in the range of 4–6 W/(m2·K) in August, November, and December, when the outdoor mean wind speeds and total rain hours are medium.

3.3.3. Seasonal Average Heat Transfer Coefficients

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis on Data Sample Size of the Naphthalene Sublimation Experiment

4.2. Effect of Envelope Surface Roughness on CHTC Calculation

4.3. Optimization Study on EHTC Calculation Model

4.4. Improvement of Meteorological Data

5. Conclusions

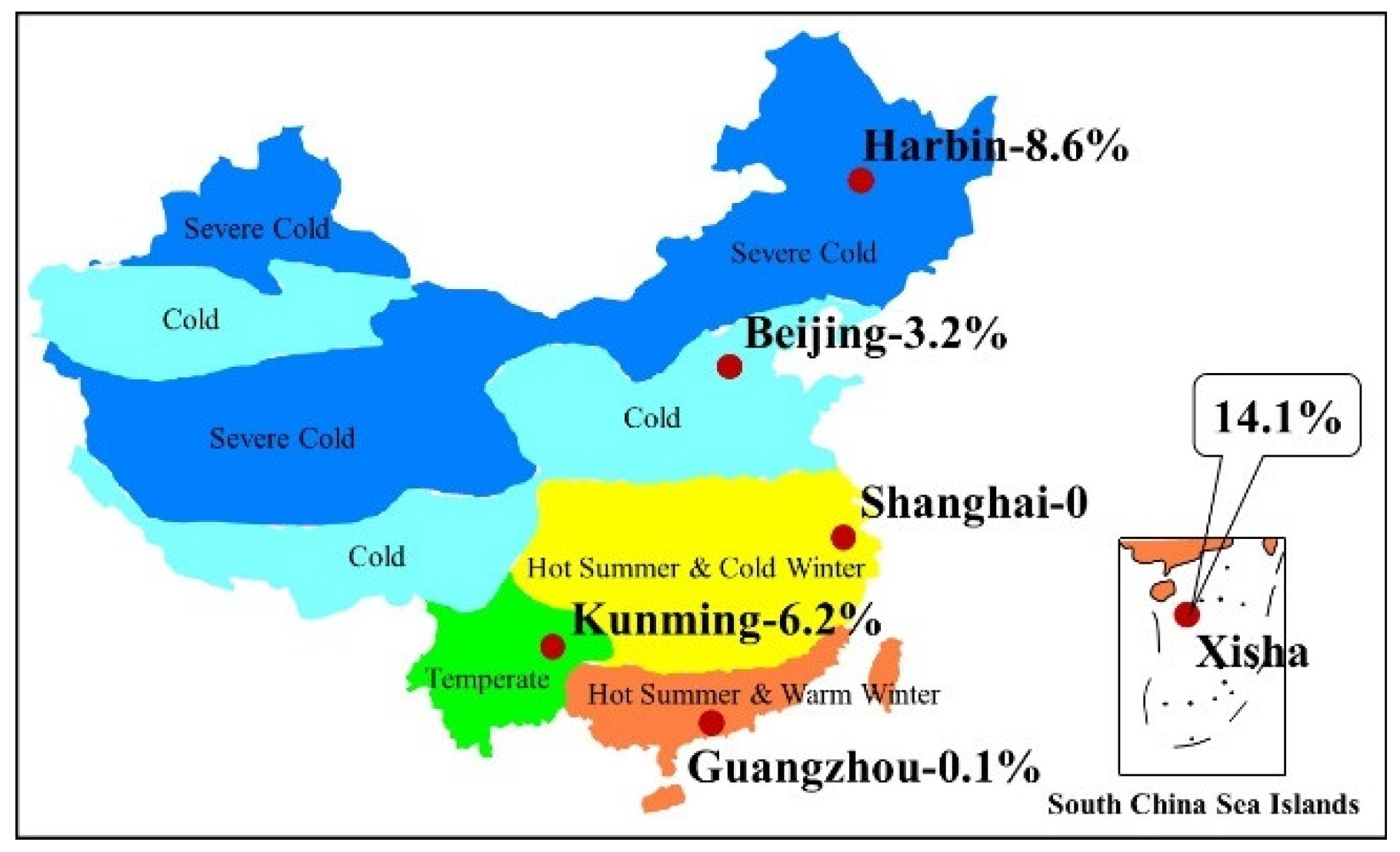

- Based on full-scale measurements in the tropical island region, the function expression between CHTC and wind speed was investigated to be CHTC = 5.56 + 4.48u (R2 = 0.94), and the CHTC predictive formula was validated to be reliable, with a mean percentage error of 2.50% for estimating CHTCs in the tropical island region.

- The characteristics of daily average heat transfer coefficients in the tropical island region were as follows: The variation trend of CHTC was coincident with wind speed, and the daily average CHTCs were all concentrated in the range of 10–60 W/(m2·K); RHTC was almost impervious to wind speed and rainfall variations, keeping unchanged at 5.8 W/(m2·K); and EHTC showed strong randomness and indeterminacy owing to rainfall effects, and it had a wider changing range from 0 to 160 W/(m2·K).

- Whether evaporation was considered or not, THTC differences were all less than 2.5 W/(m2·K) from February to May, since these months possessed relatively low or medium wind speeds and very few total rain hours. Except for the several months above, THTC differences were all more than 4.6 W/(m2·K), and for July particularly, the THTC difference reached up to 12.5 W/(m2·K) under the conjoint action of high wind speed and strong rainfall. Additionally, in terms of the whole year, the THTC difference was 5.2 W/(m2·K). Consequently, the effect of evaporation heat transfer on THTC is significant and cannot be ignored directly.

- When evaporation was taken into account, the daily average THTC ranged from approximately 16 to 220 W/(m2·K) throughout the year. Furthermore, the number of days that THTC was more than 25W/(m2·K) was 219, occupying a 60% proportion of year-round time.

- THTCs with consideration of evaporation in winter and summer were respectively 33.4 W/(m2·K) and 38.9 W/(m2·K) in the tropical island region, which are much larger than the recommended values in the current national standard.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclatures

| English symbols | |

| hc | convective heat transfer coefficient, W/m2·K |

| hd | convective mass transfer coefficient, m/s |

| hr | radiation heat transfer coefficient, W/m2·K |

| he | evaporative heat transfer coefficient, W/m2·K |

| Cp | specific heat, kJ/kg·K |

| D | mass diffusion coefficient, m2/s |

| l | representative length of target surface, m |

| u | wind velocity, m/s |

| a | thermal diffusion coefficient, m2/s |

| Nu | Nusselt number (=hl/λ) |

| Sh | Sherwood number (=hdl/D) |

| Re | Reynolds number (=ul/ν) |

| Pr | Prandtl number (=ν/a) |

| Sc | Schmidt number (=ν/D) |

| Le | Lewis number (=λ/ρCpD) |

| n | empirical constant |

| m | empirical constant |

| Ta | air temperature, K |

| Patm | atmospheric pressure close to measured position, Pa |

| Ts | test specimen surface temperature, K |

| Pv,s | naphthalene saturated pressure on test specimen surface, Pa |

| Rnapht | gas constant for naphthalene, J/kg·K |

| qra | radiation heat transfer between envelope surface and surrounding environment, W/m2 |

| Cb | blackbody radiation constant, 5.67W/(m2·K4) |

| Tw | envelope surface temperature, K |

| F1 | envelope surface area, m2 |

| F2 | atmosphere radiation area, m2 |

| Tm | average temperature between envelope surface and air, K |

| mwater | the water mass flow of evaporation, (kg/s·m2) |

| Cw | water vapor concentration on building surface, kg/m3 |

| Ca | water vapor concentration in ambient air, kg/m3 |

| Rwater | gas constant for water vapor, J/kg·K |

| Pw | water vapor partial pressure on envelope surface, pa |

| Pa | water vapor partial pressure in ambient air, pa |

| r | latent heat of water, kJ/kg |

| Greek symbols | |

| ρ | density, kg/m3 |

| λ | thermal conductivity, W/m·K |

| ν | kinematical viscosity, m2/s |

| δm | mass loss of specimen per unit of naphthalene surface area, kg/m2 |

| δt | time interval, s |

| ρv,s | naphthalene saturated vapor density on test specimen surface, kg/m3 |

| ρv,∞ | naphthalene vapor density in free-flowing air, kg/m3 |

| εwa | system emissivity |

| εw | envelope surface emissivity |

| εa | atmosphere emissivity |

| θ | temperature factor, K3 |

| φw | relative humidity on envelope surface, % |

| φa | relative humidity in ambient air, % |

| β | ratio of evaporation heat transfer coefficient to convection heat transfer coefficient |

References

- Liu, Y.X.; Luo, G.L.; Zhuang, Y. The Status and Forecast of China’s Exploitation of Renewable Marine Energy Resources. J. Coast. Res. 2015, 73, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, D.J.; Liu, Y.F.; Wang, Y.Y. Study on the effect of building envelope on cooling load in hot-humid climate. Procedia Eng. 2017, 205, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gong, X.W. The Energy Saving Effect Evaluation for Outside Wall with Different Material in Island District. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 301–303, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmel, M.G.; Abadie, M.O.; Mendes, N. New external convective heat transfer coefficient correlations for isolated low-rise buildings. Energy Build. 2007, 39, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijeysundera, N.E.; Chou, S.K.; Jayamaha, S.E.G. Heat flow through walls under transient rain conditions. J. Build. Phys. 1993, 17, 118–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MOHURD. Code for Thermal Design of Civil Building (GB 50176-2016); China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2016. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- McAdams, W.H. Heat Transmission, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. A study on the convective heat transfer coefficient of concrete in wind tunnel experiment. China Civ. Eng. J. 2006, 39, 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Choi, M.S.; Yi, S.T.; Kim, J.K. Experimental study on the convective heat transfer coefficient of early-age concrete. Ceme. Concr. Comp. 2009, 31, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazeri, H.; Blocken, B. New generalized expressions for forced convective heat transfer coefficients at building facades and roofs. Build. Environ. 2017, 119, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, M. Progress in the scale modeling of urban climate: Review. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2006, 84, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.S.; Fu, J.Y.; Xiao, Y.Q.; Li, Z.N.; Ni, Z.H.; Xie, Z.N.; Gu, M. Wind tunnel and full-scale study of wind effects on China’s tallest building. Eng. Struct. 2006, 28, 1745–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayamaha, S.E.G.; Wijeysundera, N.E.; Chou, S.K. Measurement of the heat transfer coefficient for walls. Build. Environ. 1996, 31, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharples, S.; Charlesworth, P.S. Full-scale measurements of wind-induced convective heat transfer from a roof-mounted flat plate solar collector. Sol. Energy 1998, 62, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagishima, A.; Tanimoto, J. Field measurements for estimating the convective heat transfer coefficient at building surfaces. Build. Environ. 2003, 38, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagishima, A.; Tanimoto, J.; Narita, K. Intercomparisons of experimental convective heat transfer coefficients and mass transfer coefficients of urban surfaces. Bound-Lay Meteorol. 2005, 117, 551–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Harris, D.J. Full-scale measurements of convective coefficient on external surface of a low-rise building in sheltered conditions. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 2718–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveday, D.L.; Taki, A.H. Convective heat transfer coefficients at a plane surface on a full-scale building façade. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 1996, 39, 1729–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, J.; Chen, Y.M.; Tang, G.F. Research on system identification of wall surface heat transfer processes. Exp. Heat Transf. 2002, 15, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, N.; Kimura, K.; Oka, J. A field experiment study on the convective heat transfer coefficient on exterior surface of a building. ASHRAE Trans. 1972, 78, 184–191. [Google Scholar]

- Clear, R.D.; Gartland, L.; Winkelmann, F.C. An empirical correlation for the outside convective air-film coefficient for horizontal roofs. Energy Build. 2003, 35, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhmalbaf, M.H.M. Experimental study on convective heat transfer coefficient around a vertical hexagonal rod bundle. Heat Mass Transf. 2012, 48, 1023–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palyvos, J.A. A survey of wind convection coefficient correlations for building envelope energy systems’ modeling. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2008, 28, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defraeye, T.; Defraeye, B.; Carmeliet, J. Convective heat transfer coefficients for exterior building surfaces: Existing correlations and CFD modelling. Energy Convers. Manag. 2011, 52, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirsadeghi, M.; Costola, D.; Blocken, B.; Hensen, J.L.M. Review of external convective heat transfer coefficient models in building energy simulation programs: Implementation and uncertainty. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2013, 56, 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.T.; Liu, J.; Zhao, J.N.; Zhang, W.W.; Sun, D.X.; Fu, Z.P. A novel method for full-scale measurement of the external convective heat transfer coefficient for building horizontal roof. Energy Build. 2009, 41, 840–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.T.; Liu, J.; Zhao, J.N.; Zhang, W.W.; Fu, Z.P.; Zhu, Q.Y. Field measurement of the convective heat transfer coefficient on vertical external building surfaces using naphthalene sublimation method. J. Build. Phys. 2010, 33, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodha, M.S.; Khatry, A.K.; Malik, M.A.S. Reduction of heat flux through a roof by water film. Sol. Energy 1978, 20, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodha, M.S.; Kumar, A.; Singh, U.; Tiwari, G.N. Periodic theory of an open roof pond. Appl. Energy 1980, 7, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.L.; Chen, Q.G.; Ran, M.Y.; Li, J.C.; Cai, N. Derivation of the vaporizing heat transfer coefficient he. Acta Energiae Sol. Sin. 1999, 20, 216–219. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.G. The valve of heat transfer coefficient at exterior of building envelope in heat insulation calculation. In Proceedings of the Architectural Physics Study, Chongqing, China, 1 September 2004; pp. 171–174. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.F.; Liu, J.P. Study of heat transfer coefficient of building external surface. J. Xi’an Univ. Arch. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2008, 40, 407–412. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, R.J.; Cho, H.H. A review of mass transfer measurements using naphthalene sublimation. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2015, 10, 416–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.C.; Cervantes, J.; Han, J.C.; Rudolph, R.J.; Flannery, K. Measurements of wall heat (mass) transfer for flow through blockages with round and square holes in a wide rectangular channel. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2003, 46, 3991–4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, D.H.; Jang, I.H.; Cho, H.H. Experimental study on flow and local heat/mass transfer characteristics inside corrugated duct. Int. J. Heat Fluid Fluid 2006, 27, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, K.N.; Irvine, T.F.; Karni, J. Measurement of the diffusion coefficient of naphthalene into air. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 1992, 35, 957–966. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrose, D.; Lawrenson, I.J.; Sprake, C.H.S. The vapour pressure of naphthalene. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 1975, 7, 1173–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.S.; Zhao, Q.Z. Building Thermal Process, 1st ed.; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 1986. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tao, W.Q. Numerical Heat Transfer, 2nd ed.; Xi’an Jiaotong University Press: Xian, China, 2001. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tang, R.S.; Etzion, Y. Comparative studies on the water evaporation rate from a wetted surface and that from a free water surface. Build. Environ. 2004, 39, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Instruments | Accuracy | Sampling Interval | Mounting Height |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic balance | 0.001 g | — | — |

| Temperature and humidity recorder | ±0.4 °C, ±2%RH | 30 s | 1.2 m |

| Infrared thermometer | ±0.75 °C | — | — |

| Hot-wire anemometer | (0.03 + 5% measured value) m/s | 10 s | 1.2 m |

| tm/°C | 40 | 37.5 | 35 | 32.5 | 30 | 27.5 |

| Tm/K | 313 | 310.5 | 308 | 305.5 | 303 | 300.5 |

| θ/K3 | 1.23 | 1.20 | 1.17 | 1.14 | 1.11 | 1.09 |

| RHTC/[W/m2·K] | 5.91~6.61 | 5.77~6.45 | 5.63~6.30 | 5.50~6.14 | 5.36~5.99 | 5.23~5.85 |

| Time | u [m/s] | Rain Hours [h] | CHTC | RHTC | EHTC | THTC-Y | THTC-N | THTC (Standard) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [W/m2·K] | ||||||||

| Spring | 3.02 | 45 | 19.1 | 5.8 | 1.5 | 26.4 | 24.9 | — |

| Summer | 4.56 | 118 | 26.0 | 7.2 | 38.9 | 31.8 | 19.0 | |

| Autumn | 2.91 | 175 | 18.6 | 6.9 | 31.3 | 24.4 | — | |

| Winter | 3.76 | 126 | 22.4 | 5.2 | 33.4 | 28.2 | 23.0 | |

| Whole year | 3.56 | 464 | 21.5 | 5.2 | 32.5 | 27.3 | — | |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cui, Y.; Xie, J.; Liu, J.; Xue, P. Experimental and Theoretical Study on the Heat Transfer Coefficients of Building External Surfaces in the Tropical Island Region. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9061063

Cui Y, Xie J, Liu J, Xue P. Experimental and Theoretical Study on the Heat Transfer Coefficients of Building External Surfaces in the Tropical Island Region. Applied Sciences. 2019; 9(6):1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9061063

Chicago/Turabian StyleCui, Yaping, Jingchao Xie, Jiaping Liu, and Peng Xue. 2019. "Experimental and Theoretical Study on the Heat Transfer Coefficients of Building External Surfaces in the Tropical Island Region" Applied Sciences 9, no. 6: 1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9061063