5.2. Competition

Interviewees told us that there were two dimensions on which they competed with other NPOs. First, there was competition for funding, from both public and private sources, across the art and culture sector. Second, although there may have been competition with regard to the artistic products on offer, respondents felt that their industry was characterized by a sense of cooperation at the level of the artistic product. The following two quotes [

46] sum up the opinions expressed by a majority of respondents.

- -

On competition: Our business becomes more complicated when there’s money available. I wouldn’t go so far as to say that we compete madly for small amounts, but when money is involved competition increases sharply. When a new source of funding becomes available, we’re all on our guard and start claiming that we should get it because we’re really good.

- -

On cooperation: Competition exists in the mind of the public, not in our mind. In our industry, we act much more as if we were complementary to each other than as if we were competing against each other.

In line with these quotes,

Table 4 shows that 70% of respondents sense that there is competition for funding within the industry. On the other hand, 49% sense that there is cooperation rather than competition among their artistic peers with respect to the artistic product [

47]. Several respondents told us that cooperation within the community serves to improve the quality of the artistic product in their subsector.

As a complement of information, when analyzing the results by discipline, 67% of theaters and circuses sense a higher level of competition with regard to artistic products.

Table 4.

Competition/Cooperation dimensions (total sample).

Table 4.

Competition/Cooperation dimensions (total sample).

| Average scores | Competition (%) | Cooperation (%) |

|---|

| Funding sources | 0.21 | 70 | 21 |

| Artistic considerations | 1.07 | 49 | 49 |

5.3. Socio-Economic, Political, Cultural and Legal Aspects

According to the respondents, the socio-economic impact of their decision (financial position of the government, economic conditions) was only loosely monitored [

45]. For the entire sample, interviewees said they were vaguely aware of economic issues (0.25). Looking at the results by discipline, we find that museums (−0.71) and dance companies (−0.86) are the least concerned with economic issues in their monitoring of the environment.

In contrast, when looking at the political aspect (namely, relations with funders, private donors, the community), managers overall display relatively strong awareness (1.02) of political issues: For our organization to be well positioned at the national and international levels, we need political support. We would never have access to major funding without political support.

By discipline, museums (1.80) and the music sector (1.33) show the greatest interest on this factor. Museums establish direct links on how the political issues can affect their activities.

Turning to the cultural dimension (namely, tendencies of diffusion in the media and ethnic social fabric), managers again display relatively strong awareness (0.86) of cultural issues. By discipline, we observe that, as with political issues, museums (2.00) and the music sector (1.33) show a strong interest in issues within their cultural environment. Museums establish direct links on how cultural issues can affect their activities.

Finally, with respect to the legal dimension, managers display some awareness (0.30) of legal issues. By discipline, dance (−0.43) and museums (−0.40) score the lowest on this factor, demonstrating a very superficial interest in the legal dimension.

If we split the sample by geographic area (municipalities with a population of under 500,000 or 500,000 or more), the results reveal interesting differences (

Table 5).

The political dimension has the highest score, regardless of area. However, with the exception of the legal dimension, managers in smaller municipalities speak much more about external dimensions of their environment and are concerned about how to monitor each. As a complement of information, there is no significant difference, regarding external dimensions, when we split our results between organizations in crisis and those not in crisis (

Table 6). However, it is worth noting that organizations facing a financial crisis seems slightly more aware of external dimensions than organizations not in crisis.

Table 5.

External dimensions, by geographic area (average scores).

Table 5.

External dimensions, by geographic area (average scores).

| Population | Economic | Political | Cultural | Legal |

|---|

| Population < 500,000 | 0.47 | 1.58 | 1.26 | 0.21 |

| Population 500,000 or more | 0.08 | 0.60 | 0.56 | 0.36 |

Table 6.

External dimensions (crisis or not crisis) (average scores).

Table 6.

External dimensions (crisis or not crisis) (average scores).

| In a crisis situation | Economic | Political | Cultural | Legal |

|---|

| No (23) | 0.17 | 0.87 | 0.70 | 0.35 |

| Yes (11) | 0.36 | 1.09 | 1.36 | 0.36 |

Table 5 and

Table 6 also confirm that the economic and legal dimensions are not of great interest to arts and culture NPOs in Quebec. One manager told us:

Other than poverty, socio-economic factors have no impact at all on our organization. Another confirmed this position:

We don’t pay attention to socio-economic issues ... We’re trying to sell our product whatever the economic trend is; we can’t do anything about it anyway. These two quotes sum up the opinions of our respondents with regard to economic and legal components.

5.4. Relationship with Stakeholders

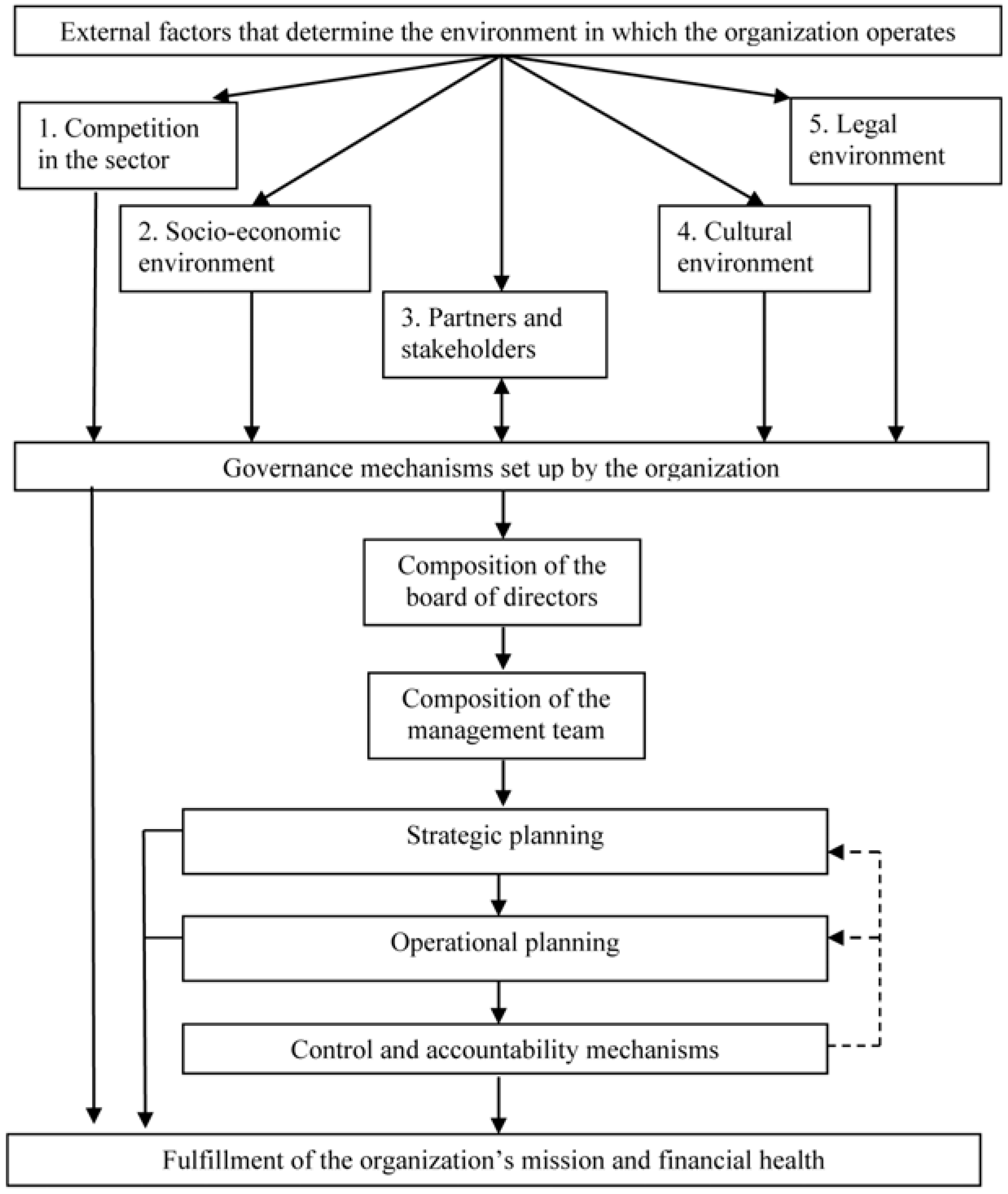

In order to capture the nature of relations between managers and major stakeholders (see the bi-directional arrow in

Figure 1, we asked managers if they felt that (1) funders are in charge, (2) funders have significant influence, (3) the partnership is balanced, (4) NPOs have significant influence over funders, or (5) NPOs are in charge. The majority of respondents said that funders have significant influence (choice #2), and this result is generalized across the sample (

i.e., choice #2 prevails irrespective of artistic sector, geographic area or whether the NPO is in crisis). One respondent said,

I’d like to move higher on your [collaboration] scale, but, realistically, they [the funding bodies] have the authority. Another commented,

I really have to be nice to them [funding bodies], otherwise...Finally, we asked respondents to assess their own influence on dimensions external to their organization. The proportion of respondents who believed they had influence on the various dimensions of their environment is shown in

Table 7. Linking the results presented in

Table 5 and

Table 6, we conclude that managers are less careful in their monitoring of those dimensions where they have no influence (socio-economic and legal).

Table 7.

NPOs’ perception of their influence on external dimensions.

Table 7.

NPOs’ perception of their influence on external dimensions.

| Total Sample | Competition (%) | Socio-economic (%) | Political (%) | Cultural (%) | Legal (%) | Funders (%) |

|---|

| 44 NPOs | 30 | 20 | 39 | 45 | 5 | 34 |

5.6. Strategic and Operations Planning

Using the same scale as that described in

Table 3,

Table 9 indicates that the managers have a good knowledge of their mission (1.20) regardless of artistic sector, size, location or financial situation (in crisis/not in crisis). Globally, managers have an interest in strategic planning (0.23) but do not support this position with convincing arguments. Looking at the data by discipline, visual arts (−0.86) have a mitigated interest in strategic planning but theaters and circuses (0.90) have a good understanding of the concept.

Table 9.

Monitoring of internal dimensions: Total sample and by discipline (average scores).

Table 9.

Monitoring of internal dimensions: Total sample and by discipline (average scores).

| Discipline | Mission | Strategic plan | Operational plan | Control and accountability |

|---|

| Visual arts (7) | 0.86 | −0.86 | 0.86 | 0.57 |

| Dance (7) | 1.57 | 0.29 | 0.57 | 0.86 |

| Museum (5) | 1.60 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.40 |

| Music (9) | 1.00 | 0.33 | 1.11 | 1.56 |

| Presenters (6) | 0.83 | 0.33 | 0.83 | 1.17 |

| Theater and circus (10) | 1.40 | 0.90 | 1.20 | 1.40 |

| Total sample (44 NPOs) | 1.20 | 0.23 | 0.95 | 1.18 |

Several quotes illustrate the degree to which strategic planning is taken seriously by the organizations surveyed:

- -

Strategic planning seems to be a trend ... In fact, it consists mainly of summing up the annual objectives, the means to achieve them and the deadlines. I’m solely responsible for all this.

- -

We do have short- and long-term objectives, but we have no formal plan. We achieve our objectives anyway but we should probably draw up a formal plan.

- -

We no longer have a strategic plan, because the last one we did is not current. The board gives us a master plan, which is more global and institutional. The “strategic” dimensions have become more operational.

- -

We’ve been working on our strategic plan for the past year and a half. We’re about to adopt it, and it’s going to completely change the orientation of our organization. We aim to become financially responsible, respect budget constraints, hire young, local talent, and offer extraordinary products.

As the results suggest, for all NPOs operational planning is a more familiar concept, which sometimes get confused with strategic planning. However, operational planning appears to be less important for managers in the dance sector than for those in other sectors. Overall, managers have a good knowledge of controls and accountability (1.18). By discipline, we note less interest within the visual arts sector (0.57).

5.7. Role of Board Members

With respect to board composition, under Quebec law the board of an NPO can include internal members who are managers (general or artistic) or employees. Although this situation is less prevalent now than it was in the past, there are still NPOs whose artistic director is the founder and also sits on the board. In a more global context, a number of laws (e.g., Sarbanes-Oxley) stipulate that the majority of the board be made up of external members. Since this is a crucial issue, we chose to address it in our empirical study.

We were also interested in an element that is of interest to many researchers in the field of nonprofit governance: the importance of having board members compensate for the lack of business expertise within an organization. Hence, we asked respondents if they believed their board members were fulfilling a role in either accountability or consultancy. Finally, other researchers have found that board members and managers have difficulty understanding their respective roles and duties. We also considered this aspect in our interview grid.

Table 10 summarizes the aspects of governance studied.

Table 10.

Aspects of governance covered in interviews.

Table 10.

Aspects of governance covered in interviews.

| Aspect of governance | Description |

|---|

| Composition of the board | Majority of internal members

or Majority of external members |

| Roles of the board | (a) Accountability: approval of budgets and financial statements.

(b) Consultancy: the organization draws from the professional expertise of its board members, who are recruited for that purpose; the board monitors external contingencies. |

| Understanding of roles | Oversight, strategic direction, committee business, fundraising, general understanding of duties. |

Again using the scale presented in

Table 3,

Table 11 shows that managers seem to have a basic understanding of the roles played by board members (0.18). They tend to believe that accountability (0.55) is an important trait for board members but not consultancy (−0.03). The visual arts sector shows the lowest scores (all under zero) for the three elements. It is interesting to note that the visual arts are the only discipline where internal members form the majority of the board (57%).

Respondents also appear to be more satisfied with the contribution of external members than with that of internal members: It is due to the contribution of members from the business community that our organization has been able to build a more professional structure; unfortunately, in Quebec there does not seem to be a tradition of involvement on the part of the business community.

Table 11.

Understanding of governance: Total sample and by discipline.

Table 11.

Understanding of governance: Total sample and by discipline.

| Discipline | Accountability Role (average score) | Consultancy Role (average score) | Understanding of role( average score) | Board: external majority (%) | Board: internal majority (%) |

|---|

| Visual arts (7) | −0.43 | −0.83 | −0.57 | 43 | 57 |

| Dance (7) | 0.57 | −0.43 | 0.43 | 100 | 0 |

| Museum (5) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.20 | 100 | 0 |

| Music (9) | 0.67 | 0.33 | 0.44 | 89 | 13 |

| Presenters (6) | 1.00 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 100 | 0 |

| Theater and circus (10) | 0.60 | −0.11 | 0.40 | 60 | 30 |

| Total sample (44 NPOs) | 0.55 | −0.03 | 0.18 | 80 | 19 |